I’ve heard that if you’ve said something twice, you should write it down. The past few years I’ve had multiple career advice calls, mentoring calls, and one-on-ones at EA Globals about operations[1] and management in EA. I’ve set up a substack called ‘Said Twice’ to practice writing (feedback is very welcome!!) and to have a place where I can write down things I’ve said at least twice. The Career conversations week on the forum gave me the final push to actually finish some drafts and publish them here and on my substack. This is my second post, see here for my first one!

--

Managing up can be worth the investment if you want to demonstrate or practice your management skills but don’t have direct reports of your own, or if you’re currently not getting what you need from your own manager. By managing up, I mean proactively helping your manager to achieve your goals. In many roles, managing up might also just be part of your job — it certainly is in my current role as chief of staff and previously as executive assistant, where I’m trying to take on as many of my manager’s tasks as possible.

I also have experience being on the other side of this: The more my employees “manage up” or help me delegate to them, the more responsibility I’ve given them and it also broadens the scope of what I think they could do in the future.

Here are three practices related to delegation that I find useful when thinking about managing up and supporting my employees:

1. Your manager’s small tasks become your big tasks

Even though it may seem like a small task when your manager is doing it, unless you’ve done it many times yourself, it will be a big task for you. Manager Tools have a useful image for this: Imagine all your manager’s tasks as different sized balls. The bigger the ball, the more complex and time consuming that task is for your manager. Very often, the type of task you’re delegated will be your manager’s smaller balls which often don’t require their particular skills and they’ve come to the conclusion that they should focus on something bigger and more complex.

The important thing about this is that when that smaller task is given to you it becomes a big and complex ball. This means that, compared to when your manager is doing the task, you will have to spend longer on the task, you’ll need more support, and you might have to use tools to help you. Your manager might just use thirty minutes to do the task, when it takes you three hours. The more you do the task, the smaller it becomes, until it becomes a small enough ball that you also spend thirty minutes on, or perhaps even automate or delegate to someone else.

Getting a new big and complex ball will also push out other balls because you only have so much space. When you get a task from your manager, you need to carve out sufficient time to do the task and identify what type of support and tools you need. This may mean pausing, delegating, or altogether removing one or more of your other tasks.

It also means identifying the type of support you need, which I’ll talk about next.

2. Identify what type of support and direction you will need from your manager

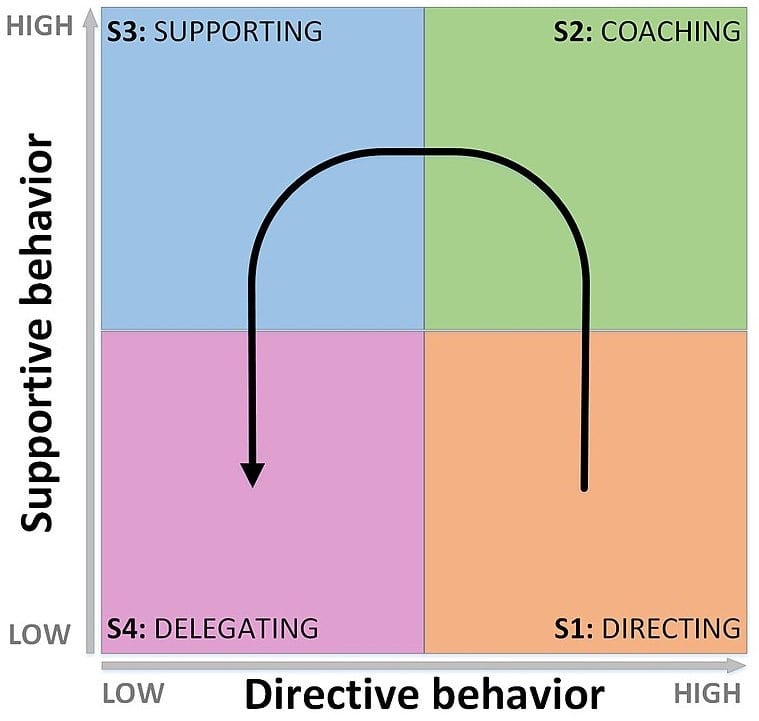

A useful concept when thinking about delegation is situational leadership, which entails adapting the level of support and direction an employee receives for every new project or task. You can see a simplified quadrant below which shows the four different combinations of supportiveness and direction.

Ftsn, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

On the one axis we have directive behaviour, or to what extent your manager is telling you how to complete the project. On the other axis there’s supportive behaviour, which means to what extent your manager engages in two-way communication with you and supports you with the project. Which of the squares is most appropriate will vary depending on the project or task at hand. To understand the quadrant above, let’s use the example of sending out multiple similar emails to 20-50 people.

Projects in “S1: Directing” are types of projects where the manager tells you exactly what to do, and you execute the tasks. These are often projects where you can follow a strict checklist, and where you’re not expected to make any decisions yourself. Using our example, in this instance your manager would make a template and create a list of who to email, and you would copy the templates to email drafts, and make sure everyone on the list is sent an email.

For projects in “S2: Coaching”, your manager still gives directions and makes the final decisions, but she asks you for input. This often entails having checkpoints or meetings whenever there’s a decision to be made. You can provide options and suggestions for what steps to take, but your manager will make the final call. In this case, maybe the manager asks you to draft a few example templates and brainstorm a list of who to send it to, and then she makes edits to and approves the final template and mailing list.

In projects in “S3: Supporting”, you’re the one making the decisions, but will ask your manager for input. These are usually projects that you have some experience with, but there are multiple decision points where it’s important for your manager to be involved. To solve our example task, perhaps you have a meeting with your manager where you ask her what the goals are for the emails and the types of people that should be on the mailing list. You might also share the template and mailing list that you’ve drafted with her, not to get her sign-off but to someone else’s eyes on it and see if there’s anything you might’ve missed.

Projects in “S4: Delegating” are completely delegated to you — you make the decisions, and aren’t required to check in with your manager throughout the project. These are projects where you have substantive prior experience, and your manager doesn’t need to be involved. In this case, the manager isn’t really involved other than for example being told whether you’re on track and when the emails have been sent.

It’s important that you and your manager have a shared understanding of which square the particular project you’re working on is in: How will your manager be involved? Who makes the decisions? How much direction will your manager give? If you’re unsure which square the project should be in, it’s generally better to start off with more support and direction, and then move along onto less support and direction as you get on, following the arrow in the illustration above.

3. If your manager doesn’t have the relevant experience, get support from someone who has

Sometimes, you’ll be delegated or proactively take on a task that your manager doesn’t have experience with themselves. In these cases, I recommend trying to get support from others with relevant experience. Either on your own or together with your manager, you can start by first identifying the particular skills or expertise needed for the project, and then generate ideas for where you can get what you need. Is there someone at another org who is doing similar tasks? Perhaps there are online courses, or a book you can read and learn from? Could you ask someone to be a coach, for example through Magnify Mentoring or other EA coaches, or coaches outside of EA?

In my experience, people are surprisingly open to help out, and there will very often be something in a podcast or book that can help you. If I need help with something related to operations or management, my first step is usually to look it up on Manager Tools — like they say themselves, there’s usually “a ’cast for that”, meaning they have a podcast episode covering the topic. (I’ll flag that their advice is very centred around middle management at companies in the US, and so you have to adapt what they say to your own situation.)

I’ll also frequently reach out to experts to ask for their advice, or if they have any policies or how-tos. Up until recently, I’ve had regular meetings with coaches with relevant ops and management experience. That was very helpful, and is where I first learned about situational leadership. My first coach was someone who had a type of job that I wanted someday, that I reached out to myself. I’ve also had a mentor through Magniy Mentoring, and am also a mentor there myself.

Identifying skills needed and people to talk to should also be part of your project description template, if you have one of those. I might talk more about that and provide a template another time!

Using these best practices in delegation isn’t the only way to practice managing up, but I’ve found them particularly useful. I often return to the image of all my responsibilities being smaller or bigger balls when thinking about my task load, and try to remember that the further down that ball goes in the organisational hierarchy, the bigger and more complex it gets. The situational leadership framework helps me figure out how much direction and support I need on a particular project, and is useful to manage expectations between me and my employees, or me and my manager, about how often and what areas we need to check in with each other about. Lastly, reaching out to experts or getting advice from my coaches have greatly helped me making those big and complex tasks smaller and more manageable. It’s also made me more deeply understand the phrase “standing on the shoulders of giants”, which I’m fortunate to do very often.

- ^

By ‘operations’ I mean project management and administrative work.

Executive summary: The author emphasizes the importance of managing up, a practice of proactively helping managers achieve their goals, and shares three key delegation practices: accepting and prioritizing delegated tasks, understanding the level of support and direction needed from the manager, and seeking advice from experienced individuals when the manager lacks relevant expertise.

Key points:

The author encourages managing up as a way to demonstrate management skills, meet personal needs, and fulfill certain job roles.

When a task is delegated from a manager to an employee, it becomes significantly larger and more complex for the employee, requiring more time, support, and possibly additional tools.

The author introduces the concept of situational leadership, which includes four categories of tasks: Directing, Coaching, Supporting, and Delegating. These categories represent different levels of involvement and decision-making by the manager and the employee.

It’s crucial for the manager and the employee to have a shared understanding of the category a project falls under, to manage expectations and ensure effective collaboration.

If a manager lacks expertise in a delegated task, the employee should seek support from others with relevant experience. Various resources, such as online courses, books, podcasts, and mentors, can be helpful.

The author finds these practices useful for managing up, making complex tasks manageable, and understanding the dynamics of delegation and support within an organization.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.