Leading teams through adversity

This post is adapted from a talk I delivered at EA Global: Bay Area in February 2025. While the style might differ from other advice on the Forum, I hope this proves valuable for leaders navigating challenges within EA organizations and projects.

TL;DR

There are unique leadership challenges when teams are facing a seemingly insurmountable problem

I’ve found four strategies for navigating crises:

Start by building agreement about the problem

Commit to the belief that your problems are solvable

Keep focus on things within your control

Invest in a high-feedback culture

Right now, in this moment we are in, I feel the intensity and challenge of our work. Across our cause areas, we are confronted with turbulent, overwhelming change. We are faced with short timelines for existential threats. Our projects that support the world’s poorest face a rapidly changing funding landscape. We are finding our footing as leaders when the stakes are as high as they’ve ever been and the way forward is unclear.

While every team overcomes obstacles in their work, I think there are unique leadership challenges when teams are faced with seemingly insurmountable problems—problems that threaten the team’s ability to continue to do their work at all.

This post will be successful if, after reading it, you feel you have a better perspective and better tools to support your hardest projects.

My first turnaround project was a clothing store. It was 2010. The name Effective Altruism had not yet been coined, Slate Star Codex had not yet launched, and Open Philanthropy was merely a twinkle in Holden’s eye.

This is the short version of what is a long story, so the important thing for you to know is that I was shot off like a cannonball to the worst-performing of the nearly 50 stores in the company. My assigned task was simple enough—run the store for about a year until the lease was up, when I would lay off the team, close the store down and head off for a better store.

When I met my new team, I found they were disconnected from the store’s financial situation and the very real consequences that loomed in front of them. They liked the status quo and they felt protective of it, and they didn’t understand the distance between their current habits and what was needed to sustain the business.

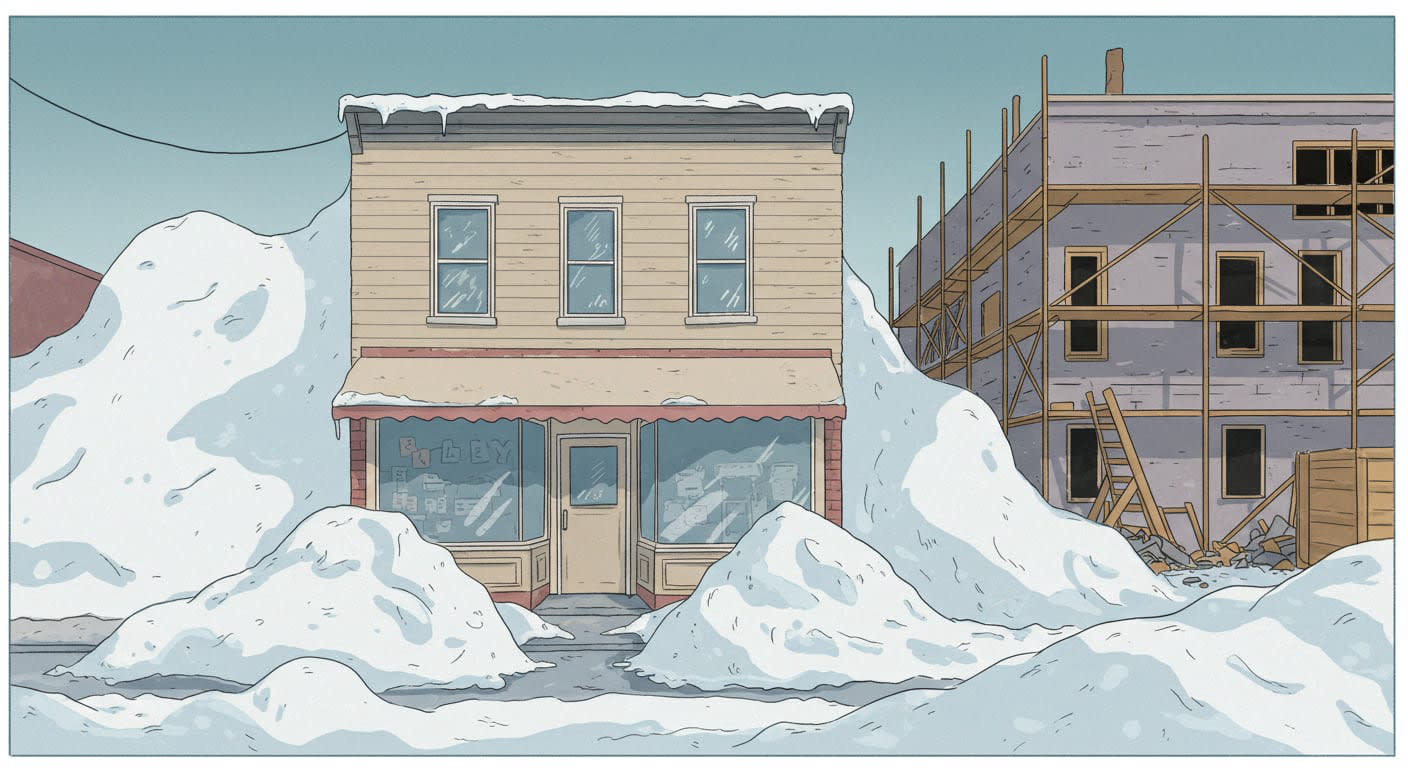

There were layers to the crisis. Not only was the store deeply in the red year after year, but it was as if the universe had decided to curse that particular year. A month or two after I moved to work with the team, construction started next door that both blocked access to the store and took up the majority of the nearby parking. And then, that winter, the city received a record-breaking 90 inches of snow. This is not hyperbole: the snow banks were higher than I am tall, and you could barely see the store even existed. In a situation like that, I cannot express how strong the instinct was to say, “Welp! This is clearly out of our control. It’s not even possible to try to solve anything right now. We’ll have to wait until the spring and try to recover then.”

“It’s out of our control.” That’s always a comfortable thing to tell yourself. How easy it would have made our work. How accurate it would have felt when we failed.

That isn’t what happened, of course. We couldn’t afford to burn up the remaining financial runway like that. The fact that recovery seemed impossible in those conditions was irrelevant. I wasn’t ready to give up, and neither was the team. Looking back, the things we did were relatively simple, but we did them with urgency, and we did them every day:

Instead of beginning with the solutions, we started by agreeing about the problem

We committed to the conceit that our problems were solvable

We held that firmly… it was everything else that we held flexibly

We kept our focus on the things we had control over

and we drew a wide circle around what we might construe as “being in our control”

We invested in a high-feedback culture

But we didn’t think about it as feedback. We thought of it as speaking the truth. That being honest was an expectation, a citizenship behavior, that was no less our work than the work itself.

After years without a single profitable month, one year after I joined, the store was at the 50th percentile of stores in terms of profitability. Two years later, it was in the upper quartile. The truth is that this kind of work isn’t actually something one person does. I never could have done this alone. I was incredibly fortunate to be joined by people who chose to sign on for the project of turning this store around, who reinforced each other, and who brought amazing gifts to the work. At the very best, as a leader, you’re just the catalyst. It’s teams that transform what is possible. The team that grew out of that time was something very special, with over half of them moving up into upper management over the years. It was a stunning transformation—the kind of result only a crisis can give you.

In this post, we’ll talk through what I learned from that little store in the snow.

1. Start by building agreement about the problem

If you’ve ever learned about wilderness survival, you’ll know that the most important thing to do if you get lost in the woods is to stop. Just stop. Stop moving, sit down if you’re able, and admit you are lost. You would be amazed how many people will not do this. Instead, without fully admitting to themselves that they’re lost and allowing themselves to take stock of the situation, they’ll pick a direction and head off urgently, getting even more lost as they go.

Even in a crisis, especially in a crisis, I want you to feel that you don’t actually have to rush straight to a solution. There are very few true emergencies—it is very, very rare that you do not, in fact, have time to stop and think.

If you rush to a solution, you create a dangerous risk. The risk that you won’t bring your team with you on the way to the solution. If you see danger up ahead, you need to stop, and confirm that your team sees the problem, too. That they agree about how important it is so that they are ready to match your energy in solving it.

If that full agreement about the problem is missing, you need to check to make sure you both have the same information. What are you seeing that they aren’t? What are they seeing that you aren’t? Someone is missing important parts of the picture.

One thing I’ve seen prevent teams from reaching clarity about the challenges they face is the leaders themselves, who avoid being specific about the most relevant facts to avoid alarming the team. If the stakes are real, we need to be able to talk about them. If we’ve hired adults, we need to treat the people we’ve hired like they’re adults.

For example, I’ve seen leaders say, “our funding runway is shorter than expected” when what the leader means is, “when we hired you, we had three years of funding runway, and right now we have three months.” We hold ourselves back from saying the full truth because we’re afraid that, if our team knew what we know, they would leave instead of staying and helping. But the leader that teams want to work for is the leader who would tell the truth in that situation. And if that’s your circumstance, you want everyone working with the full picture so they can actually help you. You need to communicate in such a way that you are at least risking success.

One of the dangers you can create if you rush straight from seeing the problem to solutions is that you might solve the wrong problem. Speaking from the experience of doing this myself, this especially can happen for seasoned leaders. They’re hired for their experience, and sometimes they extrapolate hard on what has worked for them in the past instead of looking at what they’re seeing in the here and now. This is tricky because the experience really can be an asset! But we don’t step in the same river twice, and if you find yourself too literally applying the behaviors that built your success in the past, that is a warning sign that you’re metaphorically charging through the woods when you actually need to take a seat for a beat and admit that you are lost.

And just like you need to take a good hard look at the changing conditions and a chance to consider what is familiar to you and what might be different, your team needs a chance to do the same. The truth is, that if you are faced with big challenges to your funding, or new blockers for being able to execute on your work, or other forms of major upheaval, then everyone is going to have a new job. They were hired to help you with one type of problem, but now you need them to help you with something very different.

Again, managers will shy away from having these conversations too directly because they’re worried that their team won’t want to make the change with them. It’s almost like they’re trying to trick the team into working in a new paradigm. But if changing conditions means you need to ask for something very different in their work, don’t try to hide it. Tell them the truth: their job has changed. Ask them if they want their new job. Tell them why you want them by your side in this work. Give them an authentic chance to buy in or buy out of the change.

Candidly, what this set of conversations does is it allows you to build agreement with your team that you are facing a shift in your work. That you’re about to be in the ‘after’ of a ‘before and after’. It allows them to spend as little time as possible protecting the status quo instead of identifying problems and fixing them aggressively. Your goal is to build buy-in and commitment based on a shared understanding of your new reality.

While we’re on the subject of building a shared reality, and I really can’t emphasize this enough, don’t lie. If someone asks if there may be layoffs and you’re not sure, say that. I can’t tell you how many organizations get to the point of layoffs without telling their team there was a problem in the first place or even after giving false assurances. Again, we want to have a work ethic of saying the truth, and that’s even more important when the stakes are high. Tell your team the problems you’re seeing and the possible consequences of those problems. Involve them in helping you find solutions. You don’t want to make your team helpless and powerless in the face of change—you hired them for their brilliance. Put that brilliance to work by telling them the truth. Even when it’s hard. Especially when it’s hard. That is part of what makes you someone worth working for.

2. Commit to the belief that your problems are solvable

Here’s a challenging belief to anchor on when things are tough: your problems are solvable.

For those of us who love the truth, there is tension in this belief. As we all know, there are, in fact, problems that are unsolvable. The issue, though, is that when faced with a crisis, the belief that your problems may not be solvable is self-fulfilling. It provides an “out”. That belief will prevent you and your team from being willing to fully explore the options in front of you, from being willing to change all of the things that are in your power, and from making the full measure of effort.

The belief that problems aren’t solvable protects you from doing the real work. It means you can come up with one solution and stay with it, or even worse, just keep doing the things you’re currently doing, and hope. Just hope that it all works out.

Hope. Now that’s a word I don’t actually like very much. I don’t want us to hope things get better. I want us to make things better. I want us to think flexibly, to show grit, to be creative, and be dogged in pursuit of a better world.

There’s a saying that I love, which is that every organization is a finely tuned machine to get the results it’s currently getting. What that means to me is that if you want to change the outputs, you need to be willing to change something in your status quo.

If your problem is solvable, that’s a fixed point. It gives you permission to make everything else flexible. If your problem is solvable, maybe you need to reach out to the people in your network in a different way than you ever have before. Maybe you need to think about what untapped capabilities are in the team you currently have hired. Maybe you need to challenge your business model, or your processes, or your communication, or maybe you need to make hard cuts that give you some runway back and the time to keep working on the problems. If your problems are solvable, you can explore five inadequate solutions, one after another, and then, when turning back from the fifth wrong solution, you and your team are looking for the sixth idea you need to explore. If your problems are solvable, then your work isn’t done yet, and you need to push on. This is a belief that in the face of something truly overwhelming, you don’t have to have all the answers already, but you don’t get to give up yet, either.

It’s not just your team that needs to be flexible. In the face of change, you should be a little afraid of the lessons you learned a little too well as a manager. Your team may need you to show up for them in a different way than you have in the past. They might need more challenge, or more connection, or more communication than you’ve been accustomed to giving them.

Sometimes, when managers are faced with change, they spend time protecting their so-called management style instead of engaging with the question of what the team needs from them now. But we aren’t born with a management style, and a management style isn’t a rigid extension of ourselves. Most often, it’s just patterns of behavior— ways that we’re used to interacting with our teams, something comfortable that developed semi-organically and seemed to work pretty well. But we can take the habits we’ve developed around communication, delegation, giving feedback, and supporting our teams and think about what habits will serve us best right now. When we want different results, we need to also allow ourselves, as managers, to be different.

3. Keep focusing on things that are in your control

Let’s look back at the little store in the snow. I knew then that if we used the snow to explain the revenue we were seeing, we wouldn’t seek any other (potentially more useful) explanations. So I made a silly rule: we wouldn’t use the weather to explain our revenue. What this meant is that every morning we’d talk about what it would take to be successful that day, and every evening we’d look at how much money we made and talk about what actions and behaviors helped us meet our goals or what we needed to do differently to hit our targets. And those conversations happened every day, every day, even when there were 15 inches of snow in the forecast, and we never used the weather to explain our revenue.

A very interesting thing happened: the team and I began looking at the problems we faced with an entirely different point of view. One day, when a blizzard was forecasted, one member of the team said: “Anyone who comes in today had to work hard to get here and is here for a reason—we should treat them like they have a hundred dollars in their pocket and a plan for how to spend it. They just need us to help them find what they were looking for.” That day, the store hit its target. One day, when the construction team blocked off access to the store even more than normal by closing down the sidewalk and directing pedestrian traffic away, the team re-did the front window displays with work boots and work gear to pull in the only customer they had: the construction workers. I wish I could tell you they hit the target that day, but they didn’t. But it was creative and interesting. When the weather warmed up in February for a week, the whole store was decked out in sandals and sarongs and flip-flops, which were all flipped back to winter in the next week’s cold snap. They were active, not passive. When circumstances changed, the team looked for a way to win in the new conditions.

If you’re willing to keep the things you have in control in your focus, and if you’re willing to have a fairly generous point of view on what “in your control” means, it can allow you to take a different approach to problem-solving. And there’s a funny thing about trying—if you keep trying to solve your problems, it’s often the case that you do solve your problems.

These last two ideas together—the belief that your problems are solvable and commitment to focusing on what’s in your control—are the core ideas of high ownership. They create a mindset that says, “This is my problem to fix”, rather than waiting for external factors to change. It allows your team to avoid getting stuck in the “We can’t because…” thinking and instead stay on the question “How can we?”

4. Invest in a high-feedback culture

Let’s start with “culture”, and then we’ll move to the “feedback” part.

Organizations don’t “have” a culture, they “are” a culture. Teams are more than just a collection of individuals through their norms, habits, and behaviors—that’s culture. Culture is not actually that complicated, but we make it complicated. It’s easy to get lost trying to make a nebulous “good work culture” that exists separate from and apart from the work.

Several years ago, I watched children build a sandcastle on the beach. Kids would walk up and say, “Can I join?” or just sit down and start helping. The conversation wasn’t much worth mentioning:

“You can build over here”

“If you build the towers this way, you can go higher”

“That wall is falling in”

“We need more water” “I’ll get it!”

“No, not that way. If you put the shells on too hard, it knocks it over. Do it like this”

Or even “If you want to knock stuff down, you need to build your own castle, you can’t knock down this one.”

They built the castle for hours. It was mesmerizing to watch. Here, the kids were on vacation, they were “at play,” and they were as hard at work as any of us ever are. The culture, such as it was, was entirely focused on the project. It would have been silly to try to add in some other culture over and above the work they were doing. The connection they built was the feeling of challenge, progress, and camaraderie.

After all, why did people join your team in the first place? They want to help you build something.

Yes. They also want things like to have their time be valued; to be able to have other meaningful priorities in their life; and to make their contributions legible through things like titles so they can build some durable personal capital.

But what they want day-to-day out of you and your work and your team is:

Belonging

Purpose

Growth

We get way too galaxy-brained with this. The belonging your team really wants isn’t a dedicated Slack channel to show off the team pets (although let me emphasize that that’s fun too). The belonging they really want is to know that they are the person you want to work with. That they are the person you’re making a bet on, that you believe in them, and that what they have to offer is special. That’s the belonging that counts. This project is really big and meaningful, and you, yes you, are the person I want by my side to do it.

The purpose they want isn’t just the end goal for your whole organization’s work; it is also your “why this matters” for the thing they, particularly, are doing. If they’re planning a conference, sharpen it. Say, “With 1,000 attendees here for the weekend, our goal is to make the very best use of their 20,000 hours of time because we think it can pay off in learning, context, and connections for some of the highest impact work in the world. That’s why I want you to put your best work on this project.”

The growth your team wants isn’t just promotion paths and book recommendations. It’s that you see past what they are capable of today and recognize what they could be capable of. Conversations that sound like, “You aren’t good at this part yet, but I think you could be really good at this if you put in the work.”

When you’re thinking about how to build a culture on your team, permit yourself to return again and again to the work. We don’t have to build a culture that is separate from why we are here—we all signed on for this project, and it’s okay for the way we care about each other and invest in each other and connect with each other to roll back up to the reason we’re here in the first place.

If you’re facing a crisis, the culture you need is a team of people on a mission to solve the problems with you. Who see that they are the right person for the moment, that the work is meaningful, and that they will come out of this even more capable than they already are.

So that’s the culture part; let’s talk about the feedback part.

When we think about giving feedback, a lot of times we mentally go straight to critical feedback, to the work of addressing mistakes and telling people where they could be better. Those are powerful conversations to have and, when they’re needed, I want you to have them.

But I want us to think about feedback through the paradigm of coaching. What sets great sports coaches apart isn’t that they’re the fittest—even being able to break out in a light jog isn’t a prerequisite. It isn’t necessarily that they’re the most knowledgeable. The best violinist and the best chess player alive both have coaches. What sets a great coach apart is that they put their knowledge to work through the quality of their attention. They are watching closely, and they are talking about what they see.

It sounds like this:

“Get that back elbow higher. Higher than that. Great. Take a swing. How did that feel? Try it again. Don’t worry about missing the ball this time. When you get this down, you’ll hit it more often and you’ll have even more power. Nice. That elbow was in the perfect position. Try it again.”

As a manager, you are the person who, structurally, is best positioned to pay attention, to talk about what you’re seeing, to help people who are “in the work” see the work from a different angle.

Even in teams that are experiencing major dysfunction, there will be a lot going right. Seeing what’s going well and reinforcing it is one of the most powerful tools you have. If I could only choose one, and I had to choose between positive feedback and negative feedback, it would be positive every time.

On the other hand, while we can default to a negative bias in the day-to-day feedback we’re giving—more negative than is actually true, or even useful to our teams—we also often shy away from sharing the most important critical feedback. Hard feedback is hard. With feedback that matters the most, I think we have a tendency to think too small about what “good” feedback looks like. Managers will come out of a difficult feedback conversation and say, “That went really well. They didn’t cry!” But that’s not the bar for good feedback!

I mean, it’s good. You should think over how you want to say something and care about the other person’s experience. But you win with difficult feedback when the other person trusts you more over time and has the clarity they need.

It’s okay to have a difficult conversation. By which I mean that the conversation feels difficult, that it feels emotionally intense in the moment. It’s okay for something hard to land hard. You don’t have to try to “win” the conversation by softening the message. You are not simply trying to avoid bad feels in the moment; you are trying to build a durable relationship.

As we take on challenging moments, I don’t want us to hold feedback back, while looking for the perfect way to say it.

When I’m supporting a leader, and they’re talking about a difficult relationship with a member of their team, I often ask, “What do you wish you could tell them?” And I hear things like:

“When we meet with external people, you aren’t coming in ready for the meeting. You seem distracted and disorganized. It’s hard to watch because I know you’re a really smart person, but I don’t think you’re making that impression.”

“I don’t think you trust where I’m coming from in this feedback because you think I’m not on your side. But the truth is, what I’m telling you is what I think it will take to make you successful.”

“I know what you want is a promotion, but at your level, there isn’t a road map. If we’re adding a senior role, and you’re the best candidate, it’ll be you. But I don’t know right now what would motivate us to add that role, and there’s not a clear path to how you’d be ready for it. I know that might feel unfair, but that’s the truth.”

Nine times out of ten, when someone tells me what they wish they could say, my response is, “Say that.”

And here’s the interesting thing: if you invest in a high feedback culture, you’re going to get more feedback from your team. In my experience, high feedback cultures don’t come from the manager saying, “C’mon guys, I really want your feedback.” High feedback cultures come from teams having honest conversations about how things are going every day. If you’ve built a culture where honesty is the expectation, where the work is important and where difficult problems are safe to talk about, your team will meet you there. Every time they share their perspective candidly, and you receive it with graciousness, you build trust that this is a place where honesty is the expectation. When we’re working on the world’s most pressing problems, the truth isn’t just sayable; it’s our responsibility to say it.

Leading yourself

I’d like to end with some thoughts about how you can lead yourself.

The first person you manage is yourself. In a crisis, you will need to navigate your own stress and feelings of helplessness.

If you’re lost in the wilderness, stop. If you find yourself managing from a place of stress, stop. It’s not that you don’t have time to take a beat and handle your stress; it’s that you don’t have time not to. If you can feel your field of vision tunnelling in, and your words are hard to find because your brain is flooded with cortisol, and your shoulders are up by your ears, you need to take a beat:

Make yourself a cup of tea

Step outside

Stretch

Set a timer and close your eyes

Even when things are moving very fast, you can take five minutes. Getting yourself out of a reactive headspace and into a reflective headspace is critical to your success.

The takeaway

What do I want to leave you with? It’s not hope. It’s maybe something like grit. Grit, courage, and a good box of tools.

This set of tools, from the little store in the snow

Build agreement about the problems you are facing

Make the decision that your problems are solvable

Choose to work on the things that are in your control

Invest in feedback; Work to build trust with your team that you can face the hard stuff together

I won’t tell you that crises are gifts. When you’re in a crisis, you’re just going to want to get through it. But it’s a gift to do the work that matters, to work on the hard stuff, even when and especially when it feels too hard. I think our work becomes a lot more possible when we build teams based on trust and agreement about what’s important and when we believe in our own capacities more fully. My belief is that the hardest moments are transformative. And I want us to be able to look back and know that we accomplished something at the very edge of what we thought was possible.

I found this such a beautiful piece of writing! :’)

@Anna Weldon I’ve said this before, but I am just SO excited for the managerial expertise and excellence you are bringing to CEA. We (CEA and EA) are so lucky <3