This report was conducted within the pilot for Charity Entrepreneurship’s Research Training Program in the fall of 2023 and took around eighty hours to complete (roughly translating into two weeks of work). It also was the first intervention report we ever wrote and we would do several things differently in hindsight. Please interpret the confidence of the conclusions of this report with those points in mind. Please also note that the intervention was assigned to us for this report.

For questions about the research process, please contact Leonie Falk at leonie@charityentrepreneurship.com. For questions about the content of this research, please contact Heleneor Priyanshadirectly.

The full report can also be accessed as a PDF here.

Thanks to Leonie Falk and Filip Múrar for their review and feedback. We are also grateful to the experts who took the time to offer their thoughts on this research.

Executive summary

Every year, 2.4 million babies still die within a month after their birth. Antenatal care (ANC), which includes all kinds of health services for pregnant women, plays an essential role in reducing neonatal mortality, yet many pregnant women do not attend ANC or start attending too late in their pregnancy in order to receive appropriate care. Two barriers to attending are women not knowing they are pregnant until they are already far along in their pregnancy, and not being aware about the importance and benefits of ANC.

To overcome these two barriers, the intervention in this report focuses on dispensing free urine pregnancy tests (UPTs) at the community level so that women who suspect they are pregnant are able to confirm their pregnancy. The intervention is paired with counseling on when and how to use UPTs, the importance and benefits of (early and frequent) ANC attendance, as well as how and where ANC can be accessed so women are more likely to use these tests and have their first ANC visit in their first trimester once they confirmed their pregnancy.

The evidence base for this intervention is very weak and it is unclear whether in practice this intervention would have any impact. There are no studies looking at the effect of UPT provision on earlier ANC initiation, nor is there reliable and positive evidence on the effect on CHWs’ counseling on earlier ANC initiation. Additionally, we remain quite uncertain about many of the assumptions we made in our theory of change. The only causal link which we are certain about is the one between higher ANC attendance and decreased risk in neonatal mortality—however, this relies on the quality of provided ANC, which is fairly low in many countries.

Our cost-effectiveness model of a hypothetical five-year program in India comes up with an estimate of 98.30$/DALY(lower/upper bound: 11.80–819.60$), with 38,530 averted DALYs in total (lower/upper bound: 3,228–459,941). Although our modeled intervention meets GiveWell’s cost-effectiveness bar of 100$ per averted DALY, we think our CEA is very speculative given that it is based on many estimates and imperfect proxies which we are very uncertain about.

Overall, we conclude this is a potentially cost-effective intervention but has extremely little evidence, thus we do not recommend this intervention to be used for founding a new charity.

1 Background

1.1 Burden of disease

Neonatal mortality continues to present a critical challenge in public health, particularly in low- and lower-middle-income countries. Neonatal deaths—those occurring within the first 28 days of life—make up around 47% of all under-five child deaths, totaling about 2.4 million worldwide (WHO, 2020).

Antenatal care (ANC) denotes the services offered to a mother and unborn child during pregnancy. They include maternal and fetal assessment (e.g., screening for potential health conditions), nutritional interventions (e.g., iron and folic acid supplements), and counseling on the birth as well as postpartum period (WHO, 2016). Beyond that, ANC can be used as the basis for further interventions benefitting child health, such as immunizations, nutrition programs, and breastfeeding counseling, and testing for and treating communicable and non-communicable diseases that may threaten the unborn child (Kuhnt & Vollmer, 2017).

Despite the importance of ANC for the child, availability and uptake in LMICs is still less than optimal. While the WHO (2016) recommends pregnant women receiving ANC at least four—and ideally eight—ANC visits, in LMICs, only around 64% of pregnant women attend the recommended four or more ANC visits (WHO, 2023).

1.3 Antenatal care in the first trimester

Antenatal care is especially important for women to start in their first trimester and recommended by the WHO (2016). Studies have shown that early ANC initiation, preferably within the first trimester, is associated with better neonatal outcomes, including reduced risks of preterm births and low birth weight (Doku & Neupane, 2017). This is because timely ANC initiation is crucial for early detection and treatment of complications which might have detrimental effects on maternal and fetus health (Manyeh et al., 2020; Gebresilassie et al., 2019).

Despite the benefits of early ANC initiation, many pregnant women do not have their first ANC visit until their second or even third trimester. An analysis with data from The Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) for 36 Sub-Sahara African countries found that overall timely initiation of ANC visits (i.e., within the first trimester of pregnancy) was only 38%, ranging from 14.5% in Mozambique to 68.6% in Liberia (Alem et al., 2022). This means most women in these countries do not get into the system until quite late, and cannot fully benefit from preventative and curative services before giving birth.

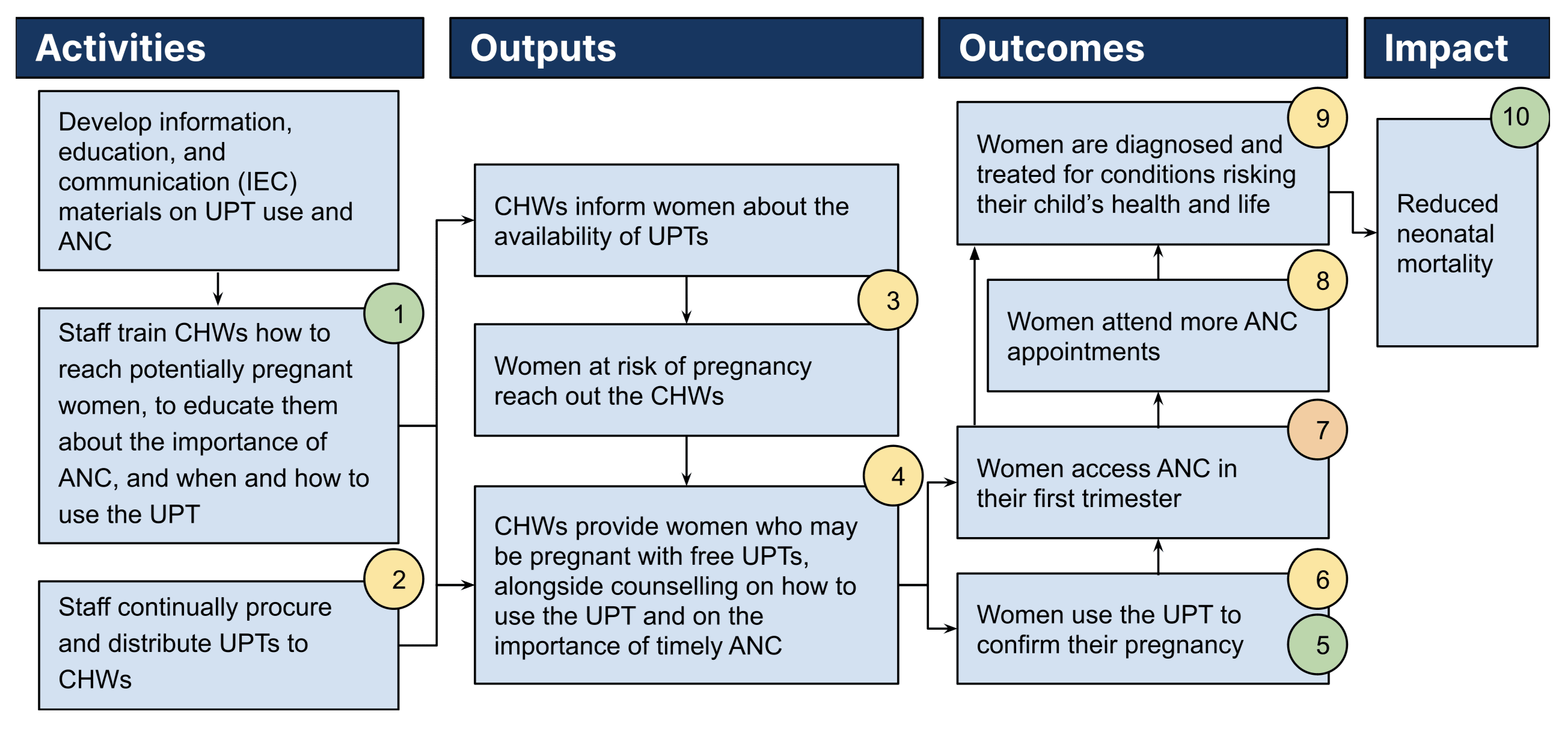

2 Theory of change

2.1 Scope of the intervention

While scoping this intervention we conducted a barrier analysis on ANC utilization in LICs and LMICs. The analysis is presented in section 3.1.1 and shows that women being uncertain about whether or not they are pregnant affects timely ANC initiation. We reasoned that, since ANC follows a schedule[1], it is likely that this also affects the total number of ANC visits made by women (since women essentially ‘miss’ their first trimester visit(s)) and logically contributes to the fact that women in LICs and LMICs do not meet the WHO recommended number of visits. Such late and low utilization of ANC in turn affects neonatal mortality. Ultimately, earlier and more frequent ANC visits should result in diagnosing and treating more conditions related to women’s pregnancy, leading to a reduction in neonatal mortality.

This intervention focuses on dispensing urine pregnancy testsand providing counseling on when and how to use UPTs, the importance and benefits of (early and frequent) ANC attendance, as well as how and where ANC can be accessed. The intermediate outcome of the intervention is to increase ANC initiation within the first trimester and, therefore, also the total number of ANC visits made by pregnant women in LMICs. By increasing ANC utilization, the intervention ultimately aims to reduce neonatal deaths.

The implementation of this intervention involves procuring and distributing UPTs to CHWs, who then spread the word that they have UPTs (perhaps framed as “quick non-invasive tests that can tell if a woman is pregnant”) and that these tests are available for free to women interested in using them (with some kind of limit e.g one test per woman and, potentially, with some kind of information on signs of pregnancy). Following this, we assume that women reach out to CHWs if they wish to use these tests and suspect they are pregnant. We have one RCT supporting this model (see section 3.1.2). Additionally, as mentioned, CHWs inform women who receive a test on the use of the test, the importance of ANC, and how they can go about accessing ANC. This allows women to confirm their pregnancy earlier, access ANC earlier, and, potentially, have more ANC visits. It also educates them on the importance of ANC, tackling a subset of barriers and misconceptions around ANC outlined in section 3.1.1 (e.g. one barrier is women believing that ANC is only required when they have health issues or pregnancy complications).

We are uncertain about whether this is the best way to increase early ANC utilization and early ANC utilization in general, because our intervention only targets potentially pregnant women who may or may not be able to make independent health decisions without the support of their families and communities. We briefly considered radio campaigns as another type of intervention that could improve ANC utilization, and think the potential impact of such an intervention deserves research. However, we chose to continue our study of urine pregnancy test dispensation, since we believe the idea showed sufficient promisingness to warrant in-depth research[2].

In addition to this, our version of the intervention initially targeted both neonatal and maternal mortality. However, while we found enough evidence on the importance of ANC and neonatal survival in our evidence review, we found limited evidence on the link between ANC and maternal deaths (see section 3.2). Hence, we chose to only focus on neonatal mortality. This is reflected in the theory of change, geographic assessment, and cost-effectiveness analysis.

2.2 Causal chain

Possible externalities of this intervention:

Increase in ANC attendance can not only reduce neonatal mortality but also reduce the risk of other neonatal conditions that do not lead to death.

Having access to free UPTs and confirming their pregnancy can enable women to access abortion services earlier, thus preventing women finding out about their pregnancy once it is too late for an abortion (see Somefun et al., 2021 and Andersen et al., 2013).

We haven’t explored these externalities in detail. However, it seems unlikely that ANC increases risk of neonatal conditions that do not lead to death. We therefore believe that this externality would positively update our conclusion on this intervention. However, we are uncertain if increase in abortions due to increased and earlier confirmation of pregnancy would result in a net positive. Whether or not abortions result in positive or negative outcomes would, amongst other considerations, depend on the quality of abortion services availed by women, which we have not looked into.

2.3 Outlining assumptions and levels of uncertainty

Our theory of change consists of several assumptions, some of which we are uncertain about. Our certainty levels for each assumption is indicated by color coding and depends on the evidence we have and our reasoning for each step (green indicates we are confident it is true, orange indicates that we think it is likely to be true, and red indicates that we are highly uncertain that it is true). These uncertainties are then further discussed and evaluated in our evidence review. The color coding of these assumptions reflects our level of uncertainty after having conducted the evidence review.

Uncertainty 1 (low): There are countries with a need for this intervention where a network of CHWs exists and it is logistically possible for staff to provide training for CHWs.

Our evidence review suggests that pregnancy confirmation is a barrier to ANC initiation and utilization in several countries studied (see section 3.1.1) and our geographic assessment finds several countries where CHWs are present (see section 5). Additionally, our evidence review also discusses related interventions in several countries that have involved training CHWs.

Uncertainty 2 (medium): The charity (or partner organizations) can procedure and distribute UPTs to CHWs on a continuous basis.

CHWs will be unable to provide potentially pregnant women with UPTs if they do not have a constant supply available to distribute. Generally, UPTs are very low-tech and seem to be very low-cost, so we expect that procurement might not be a major issue. However, distributing them to CHWs is likely to be a complex logistical challenge if the charity (or partner organizations) take care of last-mile delivery—or CHWs’ workload would increase if they have to get UPTs themselves from larger health centers which the tests are supplied to.

Uncertainty 3 (medium): CHWs successfully spread the word about the availability of free UPTs and women reach out to the CHWs operating in their communities.

We assume that CHWs spread the word that they now have UPTs (potentially framed as “quick non-invasive tests that can tell if a woman is pregnant”) and that these tests are available to women interested in using them, for free (with some kind of limit e.g one test per woman and, potentially, with some kind of information on signs of pregnancy). Following this, we assume that women reach out to CHWs if they wish to use these tests and suspect they are pregnant.

We have one RCT supporting this model (see section 3.1.2) and the model seems consistent with how CHWs provision to other medical products (like iron tablets and contraception) in the country chosen for our cost-effectiveness analysis (see section 6).

Uncertainty 4 (medium): CHWs have the ability and time to follow through on their assigned tasks.

In many countries, CHWs already perform a range of different healthcare activities around maternal care, which makes us fairly certain about CHWs’ ability to carry out the tasks relating to this intervention.

We are less certain about CHWs’ available time to follow through on their assigned task. We reviewed evidence suggesting that increasing CHWs workload does not necessarily come at the expense of other essential activities (see section 3.3). However, the degree to which CHWs are overworked and being faced with competing priorities could vary from country to country.

Uncertainty 5 (low): Women do not already have access to free UPTs.

Providing UPTs will have less effect on timely ANC uptake if many women already have access to (free) pregnancy tests. According to the literature reviewed in section 3.3, availability and costs both seem to be barriers to accessing pregnancy tests in several countries in Asia and Africa, and they are often not available at the basic primary healthcare level.

Uncertainty 6 (medium): Women are willing to use the UPT they receive (once the CHWs inform them on how to use them) and they trust the result.

Even though UPTs are provided for free, some women might choose not to use them. In order for the intervention to have an impact, UPT use would need to be high enough. Secondly, even if the women are willing to use UPTs, they may not know how to do so. However, the intervention is partly addressing women’s possible lack of knowledge on how to use UPTs since the intervention involves CHWs providing instructions on UPT use.

Uncertainty 7 (medium-high): Earlier pregnancy confirmation and receiving counseling on ANC leads to early ANC initiation.

Women’s inability to confirm their pregnancy is one of many barriers to early ANC initiation (see section 3.1.1). Therefore lowering this barrier is likely to increase ANC initiation. However, we are unsure what the extent of this increase would be, since we do not know how it compares to the scale of other barriers to early ANC initiation (also discussed in section 3.1.1). We are also unsure if ANC initiation would be the dominant result of pregnancy confirmation: some women may choose to get an abortion and not attend ANC. Finally, we have no evidence that directly looks at the relationship between pregnancy confirmation and ANC initiation.

Lack of knowledge about the availability and importance of ANC is also one of many barriers to (early) ANC attendance (see section 3.1.1). Many women may not know ANC exists, which benefits it can provide, and that ANC is recommended even in the absence of pregnancy complications. However, the evidence we find on the effect of CHWs’ counseling on ANC uptake is very weak, which is why we remain very uncertain about this assumption.

Uncertainty 8 (medium): Women who have their first ANC visit earlier in their pregnancy are able to attend more ANC visits than they would if they had their first ANC visit later.

While there are a range of barriers to accessing ANC and women can choose to no longer attend ANC after their first visit, it is plausible that early ANC initiation raises the number of visits on the margin (e.g. at least women who were going to avail ANC anyways, end up availing more ANC visits since they do not miss the first visit on the ANC schedule).

Studies have shown that early ANC initiation, preferably within the first trimester, is associated with better neonatal outcomes, including reduced risks of preterm births and low birth weight and that early ANC initiation is crucial for early detection and treatment of complications which might have detrimental effects on maternal and fetus health. This is discussed in section 1.3. This association also suggests that early ANC visits also result in more ANC visits.

Uncertainty 9 (medium): Earlier and more frequent ANC visits result in the diagnosis and treatment of more conditions related to women’s pregnancy.

This depends on the quality of ANC available to the beneficiaries of the intervention, since the intervention does not deal with the supply side of ANC. More specifically, it depends on there being at least one country in the intersection of having high quality enough ANC care but low use and/or late initiation of ANC. Initially, we assumed that the correlation between ANC quality and utilization would be high and were uncertain if such a country exists. However, our geographic weighted factor model (section 5) includes variables on ANC quality and ANC utilization and the correlation between these two variables is 0.7 (for ANC quality and ANC visits being greater or equal to four) and 0.26 (for ANC quality and first trimester visits). We think that this suggests that it is likely that there are some countries at this intersection.

Uncertainty 10 (low): Diagnosis and treatment of conditions related to women’s pregnancy result in a reduction in neonatal mortality.

Given that there is correct diagnosis and treatment of conditions related to women’s pregnancy (i.e. conditional on the uncertainty above), diagnosis and treatment of preventable conditions and risk factors of neonatal mortality would logically result in lower neonatal mortality.

Our evidence review is divided into three parts. First, we conduct a barrier analysis to identify factors that prevent timely ANC initiation and ANC utilization and provide an overview of the evidence on whether the availability of UPTs and counseling by CHWs increase ANC initiation and ANC utilization (section 3.1). Following this, we review experimental and medical literature linking ANC to neonatal mortality and maternal mortality (section 3.2). Lastly, we discuss evidence around the remaining uncertainties outlined in our theory of change (section 3.3).

Overall, the evidence base for this intervention is very weak and it is unclear whether in practice this intervention would have any impact. There are no studies looking at the effect of UPT provision on earlier ANC initiation, nor is there reliable and positive evidence on the effect on CHWs’ counseling on earlier ANC initiation. We are also very uncertain that this intervention would have any effect on maternal deaths. The only causal link which we are certain about is the one between higher ANC attendance and decreased risk in neonatal mortality—however, this relies on the quality of provided ANC, which is fairly low in many countries.

Additionally, we remain quite uncertain about many of the assumptions we made in our theory of change. This includes fundamental assumptions of this intervention, such as whether the charity would be able to tackle the logistics of distributing UPTs to CHWs on a continuous basis, whether women would be willing to use the provided UPTs and trust the results, and whether the quality of ANC is of high enough quality to actually include the necessary check-ups and treatments to lower the risk of neonatal mortality. We expect that with more time, we would have been able to review more, and more relevant studies on some of these assumptions in order to become more certain about our conclusions.

3.1 Evidence that a charity can make change in this space

3.1.1 Barriers to early ANC initiation and ANC attendance

We found several studies examining the factors behind delayed ANC access and its underutilization/late utilization in LICs and LMICs. Our focus was particularly on the relationship between women’s awareness of the significance of ANC, knowledge of pregnancy status, and delayed or infrequent ANC use.

Based on our brief analysis, we found that four of eight qualitative studies pinpointed pregnancy confirmation as a barrier to ANC utilization (this includes one of two systematic reviews included in the eight qualitative studies). And two out of five mixed-methods studies pinpointed pregnancy confirmation as a barrier to ANC utilization (this includes one of three systematic reviews included in the five mixed-methods studies). Additionally, six out of eight qualitative studies (including both systematic reviews) and four out of five mixed-methods studies (including two out of three systematic reviews) noted lack of knowledge about ANC as a barrier. Neither of the two quantitative studies we reviewed mentioned pregnancy confirmation or lack of knowledge about ANC as a factor, but this is expected since they rely on survey data which might not include pregnancy confirmation as a factor/question.

Outside of this, the studies we reviewed mentioned several other factors associated with late and reduced ANC utilization. These primarily included economic constraints, transportation and distance to health facilities, lack of support from women’s spouses or other family members, and poor quality of ANC.

A summary of the studies included in our analysis is presented in the table below (more information about each study can be found in the evidence review spreadsheet). It is worth noting that, we haven’t looked at the quality of each study or the controls it used in detail, nor whether studies overlap in systematic reviews. It is also worth noting that, although many of the studies we reviewed in fact mention lack of pregnancy awareness and lack of knowledge about ANC to be a barrier to (timely) ANC attendance, they are not reliable evidence that counseling and dispensing pregnancy tests can effectively increase ANC attendance.

Reference

Methodology

Study outcome/ focus

Barriers include lack of pregnancy awareness

Barriers include lack of knowledge about ANC

Qualitative studies and systematic reviews of qualitative studies

In general, we conclude that women’s inability to confirm their pregnancy is one of many barriers to early ANC initiation. It therefore is likely that lowering these barriers will increase earlier ANC initiation. However, we are unsure what the extent of this increase would be, since we do not know how it compares to the other barriers. This means we will look at experimental evidence for this in section 3.1.2 and 3.1.3.

3.1.2 Influence of urine pregnancy tests on ANC initiation and attendance

While lack of pregnancy awareness can be a barrier to initiating ANC in the first trimester, evidence of UPTs increasing ANC utilization is extremely limited. We found only two studies that involved distributing UPTs to CHWs, only one of which was a randomized control trial. Additionally, we found one study that looked at whether women who obtain UPTs on their own record present for ANC earlier.

Study 1: a RCT conducted in eastern Madagascar provided free pregnancy tests to CHWs who were offering reproductive services in the region (Comfort et al., 2019). The study randomized 622 community health workers into two groups[11]. In the intervention group, CHWs received a supply of UPTs and used word of mouth to let their community know about the availability of free UPTs.

The study found that CHWs in the intervention group provided services to 50% more women (6.3 vs 4.2 women), that more women knew they were pregnant at the end of their visit to the CHW (95% vs 10% women), and that a higher number of clients received ANC at the visit (67% vs 28%)[12]. All three results were statistically significant at p < 0.01 or p < 0.001. However, the study does not analyze whether ANC utilization increased after this visit to the CHWs.

Study 2: A second study in Nepal involved a similar intervention and studied the link between providing CHWs with UPTs on referrals to reproductive health services (Andersen et al., 2013). The study involved training 1,683 CHWs, 89% of which provided follow-up data at eight months. Of these, 80% reported providing UPTs to women during the follow-up period, with 3.1 UPTs dispensed per CHW on average. 53% women tested positive for pregnancy and the CHWs referred 32% of them to safe abortion services and 68% to ANC. However, the study did not provide baseline values. It is therefore not informative on whether providing UPTs to CHWs increased pregnancy confirmation or referrals to reproductive health services.

Study 3: A third study was an observational study that analyzed cross-sectional data on 158 women presenting for ANC and 164 women presenting for abortion in Cape Town, South Africa (Morroni & Moodley, 2006). It found that women who obtained UPTs of their own record presented for ANC earlier, while women who were sent from public health clinics to buy and use a UPT presented for ANC later. However, the control group was not clearly specified and there could be enough confounding factors at play to draw a sound conclusion from this paper.

In summary, given the methodological issues with Andersen et al. (2013) and Morroni & Moodley (2006), we can only draw conclusions from Comfort et al. (2019). Andersen et al. (2013) suggest that pregnancy confirmation through UPTs can change intermediary outcomes like client care-seeking behavior and services offered by the CHW. However, we are unsure of whether these results generalize to different contexts. We also cannot conclude that distributing UPTs leads to increased ANC attendance, since the study did not look at this particular outcome measure.

3.1.3 The role of CHWs in increasing early ANC initiation and ANC attendance

While one part of this intervention consists of CHWs dispensing UPTs to potentially pregnant women, the other part consists of CHWs providing counseling on the importance and benefits of (early and frequent) ANC attendance as well as in which health facilities ANC can be accessed. This should increase the likelihood of women attending ANC earlier if they confirm their pregnancy with the UPT they receive.

Our intervention is based on CHWs spreading information about free UPTs within their communities and women coming to see them in their clinics to obtain a test. However, almost all of the evidence we found on the effect of CHW counseling on behavior change, specifically on (earlier) ANC attendance, focuses on home visits made by CHWs. This approach is different to the one used in our intervention and thus the studies reviewed below are only of limited generalizability. Another limitation of the evidence is that all the studies we reviewed look at CHWs counseling pregnant women on ANC, not potentially pregnant women like it would be the case in our intervention.

The methodologically strongest study is a meta-analysis of 34 studies; however, the study pooled results from very different kinds of interventions (the shared denominator being community-based interventions to improve ANC uptake). It did not find significant results in terms of increased or earlier ANC attendance (Mbuagbaw et al., 2015).

Next, the RCTs we reviewed return mixed results:

Kayentao et al. (2023) report positive results on significantly increased likelihood of at least one ANC visit, four or more ANC visits and early ANC initiation.

Regan et al. (2023) report a significantly increased likelihood in attending four or more ANC visits but no significant increase in early ANC initiation.

Geldsetzer et al. (2019) do not find significant results in terms of increased or earlier ANC attendance.

The two weaker studies (in terms of methodology, with one being an observational study and the other one a difference-in-difference study) report more favorable evidence on CHW counseling:

Hijazi et al. (2018) find that ANC attendance is correlated with receiving information or education on ANC.

Wafula et al. (2022) find that counseling by CHWs resulted in a significantly increased likelihood of attending four or more ANC visits but found no increase in the likelihood of early ANC attendance.

Overall, the results are inconclusive. Considering the very limited generalizability of these studies, we interpret the evidence above as extremely weak evidence for CHWs counseling to increase the frequency of ANC visits, and do not regard it as evidence for CHWs’ counseling to increase ANC attendance in women’s first trimester.

3.2 Evidence that the change has the expected effects

3.2.1 Influence of (early) ANC on neonatal and maternal mortality according to field literature

In general, we found limited evidence on whether or not ANC reduces risks of maternal mortality. With respect to neonatal mortality, we found limited evidence on the impact of early ANC initiation but sufficient evidence on ANC overall.

We did not look at any of these studies in detail, and several confounding factors[13] may or may not have adequately controlled for in the non-randomized studies.

Studies looking at whether ANC was provided and/or the number of ANC visits:

Study 1: We found a Cochrane review of RCTs looking at whether reducing the number of ANC visits affected mortality (Dowswell et al., 2010). The review included four trials from HICs and three trials from LICs and found that reduced ANC visits negatively affected perinatal mortality (which was an outcome variable for five trials and was driven by results of trials in LMICs and LICs) but did not significantly affect maternal death (which was a variable for three trials, RR 1.13; 95% CI 0.50 to 2.57). However, the result for the latter has a large confidence interval and is therefore not very informative.

Study 2: Tekelab et al. (2019) conducted a systematic review of 12 studies in Sub-Saharan Africa. According to the systematic review, receiving ANC by a skilled provider was associated with lower neonatal mortality in five of the 12 studies. The review used a random-effects model and found a pooled risk ratio of 0.61 (95% CI: 0.43–0.86) and concluded that “utilization of at least one antenatal care visit by a skilled provider during pregnancy reduces the risk of neonatal mortality by 39% in Sub-Saharan African countries”.

Study 3: Tiruye et al. (2019) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 27 studies in Eastern Africa and found that “having at least 1 ANC visit during pregnancy reduced the risk of neonatal death by 42% compared to their counterparts (RR = 0.58, 95% CI [0.47, 0.71]). The pooled prevalence of NM was 8.5% (95% CI [7.3, 9.6]), with NM [neonatal mortality] rate of 46.3/1000 live births.”

Study 4: Kuhnt & Vollmer (2017) used Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data from 1990 to 2013 to analyze nationally representative data of 69 LMICs and MICs. They found that at least one ANC visit was associated with 1.04 percentage point decrease in neonatal mortality and that having at least four ANC visits and seeing a skilled provider at least once was associated with an additional 0.56 percentage point decrease in neonatal mortality. These results were statistically significant.

Studies looking at ANC timing and ANC visits:

Study 5: Doku & Neupane (2017) analyzed nationally representative cross-sectional data across 57 LMICs from 2005 to 2015, captured in the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). Their pooled analysis found a “55% lower risk of neonatal mortality [HR 0.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.42–0.48] among women who met both WHO recommendations for ANC (first visit within the first trimester and at least four visits during pregnancy)”. Additionally, the risk was 32% lower for women who met one of these two WHO recommendations. However, ANC attendance was not associated with lower risk in the Middle East and North Africa.

Study 6: Saaka et al. (2023) is an observational study that looked at the joint effect of ANC timing, frequency and content on low birth weight (LBW) and preterm delivery (PTD). The study, with a sample size of 553 postpartum women, and found that, after controlling for confounders, both risk of LBW (Adjusted OR = 0.44 (95 % CI: 0.23, 0.83)) and PTD (Adjusted OR = 0.29 (95 % CI: 0.15, 0.59) were lower for women who had more timely, more frequent and better quality ANC visits.

In general, we found limited evidence on whether or not early and or more ANC visits reduce maternal mortality. We found sufficient evidence to suggest that ANC visits reduce neonatal mortality and evidence suggesting that early ANC initiation along with number and quality of ANC reduces neonatal mortality. While Doku & Neupane (2017) mention the effects of first trimester visits, it does so in conjunction with the number of visits. Hence, we choose to estimate the percentage decrease in neonatal deaths based on Kuhnt & Vollmer (2017) and model our CEA accordingly (see section 6). We think this is a justified decision since the effect sizes of the two studies are similar[14].

Our research is far from exhaustive and we believe that allocating more time to the review would have yielded more evidence. We believe that such evidence would be directionally the same for neonatal mortality given the type and sample size of the studies we came across and reviewed but we are unsure of what such evidence would mean for the association between ANC and maternal mortality.

3.2.2 Influence of (early) ANC on neonatal and maternal mortality according to the medical literature

In addition to the field literature on the influence of (early) ANC attendance on neonatal and maternal mortality in LMICs, we also reviewed medical literature to get a better sense of what causes of neonatal and maternal mortality can be addressed during ANC, and especially during ANC in the first trimester.

According to medical literature, infections and prematurity are two of the leading causes of neonatal death, each accounting for more than a quarter of neonatal deaths (Wright, 2012):

Infections: STIs can be transferred from mother to child in utero (Bale et al., 2003), but can be prevented by medication during pregnancy (John Hopkins Medicine, n.d.). For example, syphilis can be easily treated with antibiotics, but ideally as early as possible in a woman’s pregnancy to reduce the risk of mother-to-child transmission (Murár, 2023). UTIs, if untreated, can lead to pyelonephritis, which can cause preterm delivery (Bale et al., 2003). Tetanus is another risk factor for neonatal death, and mothers can be immunized against tetanus during pregnancy (Bale et al., 2003).

Preterm birth: Prematurity can be caused by hypertension (WHO, 2023). Incidentally, hypertension is also one of the leading causes of maternal death (Say et al., 2014). Hypertension requires close monitoring during the pregnancy and women are recommended to start taking drugs, ideally at the end of their first trimester, in order to reduce the risk of prematurity (Beech & Mangos, 2021; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2019).

We also interviewed Sophia Seidler (a fellow RTP participant and pediatrician at the University Medical Center Goettingen since 2020) on the causes of maternal and neonatal mortality as well as potential treatments during ANC. She emphasized that early ANC allows for crucial counseling on avoiding toxic substances like alcohol and tobacco (which is associated with higher risks of preterm birth, which in turn is a major reason for neonatal mortality (Albertsen et al., 2004; Wisborg et al., 1996; Wright, 2012). This type of counseling can easily be incorporated into ANC programs in low-income countries as it requires no special medical equipment. Another benefit is timely nutritional counseling, specifically regarding folic acid and iron, and, relatedly, the provision of supplements. Lack of folic acid increases the risk for disabilities in children, such as open backs, which in turn increases the risk of infection and neonatal death. Iron deficiency can also increase the risk of maternal mortality, particularly in cases of blood loss at birth (anemia accounts for 9% of maternal deaths (Sitaula et al., 2021)).

All of the above primarily address neonatal mortality, not maternal mortality. Given that in the literature we reviewed in section 3.2.1 we also could not find any effects of ANC on the risks of maternal mortality, we decided to exclude maternal mortality from the scope of this intervention, and will thus also exclude it from our GWFM and CEA.

One caveat for the reviewed medical evidence is that the discussed methods for diagnosing and treating causes of neonatal and maternal mortality might not be broadly available in LMICs given the generally lower quality of healthcare in many countries. The question of ANC quality is further discussed in section 3.3.

3.3 Evidence on other key uncertainties

3.3.1 The charity (or partner organization) can procure and distribute UPTs to CHWS on a continuous basis

As for the procurement of UPTs, we weren’t completely able to confirm continuous availability of UPTs on the LIMC market. However, Arizton (2023) writes that “the global pregnancy test kits market is highly competitive and has many global, regional, and domestic players offering a comprehensive product portfolio of pregnancy test kits”. This and the fact that pregnancy tests are quite low-tech and cheap—the median price per unit is less than $0.10 (International Medical Products Price Guide, 2015)—makes us quite confident that pregnancy tests are generally available in LMICs for a charity or its partners to buy in bulk and dispense to CHWs. If they are not continuously available in LMICs, an organization could buy pregnancy tests in HICs, where the supply is likely to be more stable, and provide them to CHWs in LMICs—however, this would supposedly greatly increase (shipping) costs.

As for the distribution of UPTs to CHWs, we are uncertain how an organization may best distribute UPTs to each individual CHW. Ultimately, we think the logistical complexity of this intervention would greatly increase if the last-mile delivery of UPTs to CHWs was done by the organization itself. In contrast, if UPTs were delivered to a bigger health care facility where individual CHWs could pick them up, this would increase the workload of CHWs depending on how often they would need to travel to the health care facility to restock their supply of UPTs. It would be worthwhile to look into how CHWs usually get their material and equipment in order to better how to best handle these logistics.

3.3.2 CHWs successfully spread the word about the availability of free UPTs and women reach out to the CHWs operating in their communities

The pathway of women obtaining a UPT through CHWs is loosely based on Comfort et al. (2019): women hear about the availability of free UPTs at their CHW’s clinic and visit the CHW to obtain a test. Women who obtain a test might currently suspect they are pregnant or obtain a test for a future point in time at which they suspect they are pregnant. Crucially, the information about available pregnancy tests could also increase the women’s saliency of pregnancy, leading them to more often suspect them to be pregnant. The (cost-)effectiveness of this intervention would partly depend on how well women can identify themselves as being at risk of pregnancy. The better able women are to correctly suspect they are pregnant, the fewer tests would be handed out. Given the lack of time to gather more evidence on this assumption, we remain uncertain about it.

3.3.3 CHWs have the ability and time to follow through on their assigned tasks

There are several pieces of evidence that make us fairly certain in CHWs’ ability to provide services to women as prescribed by the intervention:

There are several studies on interventions leveraging CHWs to provide services on antenatal care, postpartum care and contraception. Judging by these studies, it seems possible to successfully engage CHWs in large-scale interventions about ANC (Comfort et al., 2019; Kayentao et al., 2023; Kachimanga et al., 2020).

Madagascar has “task-shifted some of the provision of contraceptives to CHWs as a way to expand access to FP [family planning] among women in remote, rural areas” (Comfort et al., 2016). We do not know whether this particular instance of task-shifting to CHWs has ever been evaluated. Nevertheless, we take the above as weak but positive evidence that CHWs would be able to successfully provide UPTs and counseling on ANC if they can do the same with contraception. We assume the government of Madagascar has a certain level of trust in the capabilities of CHWs or otherwise they would not have tasked them with the provision of contraceptives.

According to the WHO (2020), CHWs often perform a variety of tasks, including delivering diagnostic, treatment or clinical care, encouraging uptake of health services, providing health education and behavior change motivation, data collection and record-keeping, improving relationships between health system functionaries and community members, and providing psychosocial support. We take this as additional weak evidence that CHWs are well-suited to conduct the tasks involved in this intervention.

Another important aspect to consider is whether CHWs would have the capacity to deliver high-quality ANC counseling and UPT dispensation given their already existing workload. There are a few specific studies looking at CHWs’ workload and the change in service quality if additional tasks are added to CHWs’ duties. These studies have not been conducted in the realm of UPT dispensation or ANC, so they are of somewhat limited generalizability. Nevertheless, they find that increasing CHWs workload does not necessarily come at the expense of other essential activities. Instead, CHWs reduce their time spent on non-work activities, and the increased workload has effects on their domestic life[15][16][17] (Puett et al., 2012; Chinkhumba et al., 2022; Astale et al., 2023).

From the above we conclude that when implementing this intervention, making sure CHWs do not suffer from an increased workload is important. The scope of the service CHWs provide for this intervention is not only to dispense UPTs to women at risk of pregnancy but also to provide instructions on when and how to use UPTs as well as counseling on the importance of ANC. The extent of the counseling part on UPTs and ANC might thus be seen as a tradeoff between the amount of information women need to receive in order to maximize correct use of UPTs and uptake of ANC, and the amount of work added to CHWs existing responsibilities. Offloading last-mile delivery of UPTs to CHWs (as addressed in section 3.3.1) could also come at the expense of CHWs time and should be considered when implementing this intervention.

3.3.4 Women do not already have access to free UPTs

We are fairly certain that many women in LMICs do not have access to affordable pregnancy tests based on the following evidence:

Cost as a barrier:

Comfort et al. (2019) study the effects of dispensing free UPTs on ANC attendance and remark that in their study setting in Madagascar “tests had not previously been available outside of health centers, and their prices tended to be significantly marked up“.

Kennedy et al. (2022) reports that “[w]hile urine pregnancy self-tests are available over-the-counter in many high-income and middle-income settings, in many low-income settings, they may be financially inaccessible to most people outside of public health services, or unavailable altogether, leading individuals with the sole option of health facility-based blood tests to confirm pregnancy”.

Nganga et al. (2021) remark that in Kenya UPTs are often only available in pharmacies, which sell them with a markup, making them unaffordable for many women. Additionally, they found lack of money to pay for the test as one major barrier to getting UPTs.

Mazumder et al. (2023) found cost as one of the main factors for women not to use pregnancy tests in Kenya.

Availability as a barrier:

Comfort et al. (2016) report that women in Madagascar are sometimes faced with stock outs of tests in LMICs.

Mazumder et al. (2023) found availability as one of the main factors for women not to use pregnancy tests in Kenya.#

Yadav et al. (2021) found that urine pregnancy tests are commonly available in hospitals in LMICs but less so at the level of primary health care:

3.3.5 Women are willing to use the UPT they receive (once the CHWs inform them on how to use them) and they trust the result

Nganga et al. (2021) found that the major reasons for non-use of pregnancy tests was not thinking it was necessary and lack of knowledge about UPTs. Our intervention aims to lower the barrier of these factors, since CHWs would dispense UPTs for free and provide counseling on early signs of pregnancy as well as how to use UPTs.

Other barriers to using UPTs include lack of support from women’s partner, mistrust of accuracy in the test, preferring to rely on sign and symptoms pregnancy, and preferring to getting a test from a health facility (Ramei et al., 2023; Mazumder et al., 2023). While the trust in the test is something that could be addressed by the CHW while providing counseling, the lack of support from a woman’s partner is not. This is partly the reason why we included the Gender Inequality Index in our geographic assessment to select for countries with higher gender equality where women hopefully have greater autonomy over their own health choices.

3.3.6 Women who have their first ANC visit earlier in their pregnancy are able to attend more ANC visits than they would if they had their first ANC visit later

Although we couldn’t find any field studies on the influence of early ANC attendance on the total number of ANC visits a pregnant woman has, the logic of the connection between the two is compelling to us. Two more pieces of evidence increase our certainty in this assumption

In CE’s report researching the use of mobile phone reminders to promote ANC attendance (Hodgins & Murár, 2023), one of the interviewed experts pointed out that late ANC initiation gives women limited time to have the recommended number of ANC visits.

Benova et al. (2018) show that in the Democratic Republic of Congo, women who initiate ANC in their first trimester attend more visits than women who start ANC later in their pregnancy. However, this relationship is not causal and it could likely be the case that the relationship is mediated by, for example, ease of access to ANC.

However, as we found out in the barrier analysis (see section 3.1.1), women are faced with a number of hurdles when it comes to ANC, including quality of care, disrespect or abuse from health staff, distance to health facilities, and cost of ANC visits. Thus, it could be that after a woman’s first visit in her first trimester, she decides to no longer continue with ANC based on the hurdles above. Overall, we conclude that an ANC visit in the first trimester is a necessary but insufficient condition to completing all four WHO-recommended ANC appointments.

3.3.7 The quality of care during ANC is sufficient to improve mothers’ and children’s health outcomes

If the quality of care women receive during their ANC visits fails to impact neonatal mortality, then trying to increase (early) ANC attendance is of little benefit. The evidence we reviewed on ANC quality is mixed:

Arsenault et al. (2018) study ANC quality in 91 LMICs and find that on average, 63% of women report blood pressure monitoring and urine and blood testing at any point during the pregnancy among those who had at least one visit with a skilled antenatal care provider.

Benova et al. (2018) study ANC quality in 10 LMICs and report that “the self-reported content of care was suboptimal even among women meeting recommendations on number of ANC visits and timing of first visit at the time of survey”.

Arroyave et al. (2021) carry out a meta-analysis on ANC quality in 63 LMICs and devise an ANC-quality score (ANq, ranging from 1 to 10), which is reversely correlated with neonatal mortality. They find that the mean ANCq is 6.7 and that 57.9% of women receive ANC care according to an ANCq score of 8 or 9. They report that on average, blood pressure is measured in 92.5% of women, a blood sample is drawn from 85.9%, a urine sample is collected from 82.5% and 2+ tetanus injections are given to 55.56%.

In our barrier analysis (see section 3.1.1), disrespect, mistreatment and abuse by health staff is sometimes mentioned as a barrier to ANC.

Overall, the evidence on ANC quality is quite mixed. On top of that, only one of the three studies above report on how the observed ANC quality stands in relationship with neonatal mortality. This is why we remain very uncertain about this assumption.

In our geographic assessment, we include ANC quality as one of the factors, since this intervention is ideally implemented in a country with relatively high ANC quality, for reasons outlined at the beginning of this section.

4 Expert views

We reached out to Ben Williamson, who co-founded the Maternal Health Initiative (MHI), a charity incubated by Charity Entrepreneurship. MHI works in Ghana, a country which we identified as a potential target location for this intervention (see our geographic assessment in the next section). We posed the following questions:

Do women in Ghana usually have difficulties finding out whether they are pregnant or not? What’s the use and availability of urine pregnancy tests?

To what extent is pregnancy confirmation a barrier to accessing antenatal care and how does it compare to other barriers such as high costs or low quality of antenatal care?

In your experience, when training healthcare workers to provide additional services, how has this affected healthcare staff’s workload and service quality?

Ben mentioned that he hadn’t come across pregnancy detection as a barrier in his work in Ghana and that attendance of early ANC appointments tended to be low for cultural reasons (the pregnancy must be presented/recognised in the community before a woman will go to a health center for care). Outside of this, he was of the opinion that it would likely be feasible to train healthcare workers in tasks that place limited demands on their time and that pregnancy test delivery wouldn’t cause service quality/workload issues.

These observations corroborated our conclusions from the evidence review. We chose not to reach out to or follow up with the other experts due to time constraints and because we don’t expect expert views to substantially change the conclusions of this report.

We developed a geographic weight factor model (GWFM) to identify countries which would be well-suited for implementing this intervention.

Ideally, this intervention would be implemented in a country that fits the following criteria:

High neonatal mortality

Low attendance of ANC and late ANC initiation (i.e., after the first trimester)

High number of women not being able to easily confirm their pregnancy

High number of women living in close distance to ANC units, being able to afford the (direct and indirect) costs of ANC, and not facing many other barriers to attending ANC (e.g., they get their family’s approval or are able to make their own health decisions)

Sufficient quality of antenatal care services, including check-ups and treatments relevant for reducing neonatal mortality

High number of CHWs and ANC health staff

Sufficient infrastructure and logistical capability to deliver UPTs to CHWs

However, we did not find exact data for some of these criteria, which is why we used imperfect proxies. Ultimately, we included the weighted consideration of the following factors:

5.1.1 Scale (40%)

Neonatal deaths (22.5%) (calculated applying the neonatal mortality rate per 1000 live to the total births in the country)

4 or more ANC visits (7.5%) The percentage of women aged 15-49 with a live birth in a given time period that received antenatal care four or more times.

First trimester ANC visits (10%) The “proportion of women aged 15–49 years with a live birth in a given time period who initiated their first antenatal care visit in the first trimester (<12 weeks’ gestation) in the same period” (Mollar et al., 2017).

Our intervention is aimed at reducing neonatal deaths and the first factor tells us how many people the intervention is (theoretically) able to reach in a country.

Since the intervention aims to reduce neonatal mortality by promoting ANC attendance, this intervention is best-suited for a country with low ANC attendance rates and late ANC initiation.

One factor we wanted to include but could not find any data on is women’s ability to confirm their pregnancy or the prevalence/usage of pregnancy tests.

5.1.2 Tractability (55%)

Indices (10%)

Ease of Business Ranking (2.5%)

Fragile State Index (3.5%)

Gender Inequality Index (4%)

Health Workforce density (15%)

Doctors per 10,000 (3.75%)

Nurse and midwives per 10,000 (3.75%)

Community Health Workers (CHWs) per 10,000 (7.5%)

ANC Quality and Coverage (30%)

Antenatal Care Quality (15%) “Antenatal care quality is defined as the proportion of women who report blood pressure monitoring and urine and blood testing at any point during the pregnancy among those who had at least one visit with a skilled antenatal care provider” (Arsenault et al., 2018).

Antenatal care coverage (15%) “Antenatal care coverage is defined as the proportion of women with at least one live birth in the past 2 or 5 years who had at least one visit with a skilled provider” (Arsenault et al., 2018).

To model the tractability of the intervention, we included the Ease of Business Ranking and Fragile State Index to account for the ease of operability of a charity in a country. We also included the Gender Inequality Index which acts as a proxy for how autonomous women are in their health decisions. Not being able to make independent decisions (and instead having to seek approval from their husband or mother-in-law) came up as a barrier to using UPTs (see section 3.3.5) and attending ANC (see section 3.1.1).

The number of active CHWs per 10,000 capita tells us more about if it is feasible to use CHWs as a pathway to dispense UPTs and information about ANC to pregnant women, and about the capacity of CHWs to handle the additional task on top of their existing workload (i.e., if there are few CHWs per 10,000 capita, CHWs are likely to be unable to address a large proportion of pregnant women and to be overwhelmed with their existing workload). The number of doctors as well as nurses/midwives per 10,000 capita should tell us about the overall capacity of the health care system to deal with the additional ANC attendance of pregnant women this intervention aims to generate. The number of doctors and nurses/midwives also serves as a kind of proxy for the quality and coverage of ANC. We also include direct data about ANC quality and coverage. These two factors are crucial, since aiming to increase pregnant women’s ANC attendance adds little benefit if women cannot access ANC despite wanting to do so. Similarly, increasing pregnant women’s attendance of ANC is not very valuable if the quality of ANC is low and fails to reduce neonatal mortality.

5.1.3 Neglectedness (5%)

Number of organizations already working to increase antenatal care utilization and/or early antenatal care utilization (5%)

Due to time constraints, neglectfulness was not reviewed. The top 10 countries were identified based on the scale and tractability criteria alone. This means that the weights for all other factors are scaled accordingly[18].

The top-10 countries identified by our model are as follows:

India

0.640

Kenya

0.589

(Tanzania)

0.421

Nigeria

0.372

Ghana

0.371

Côte d’Ivoire

0.347

Rwanda

0.335

Uganda

0.308

Lesotho

0.307

(Congo, Dem. Rep.)

0.281

Tanzania and Congo, Dem. Rep. have missing data on the number of CHWs since the intervention relies on CHWs to carry out services to potentially pregnant women.

5.2 Where existing organizations work

We spent around one hour researching existing organizations, but our search did not result in any findings. Neither keyword searches for free UPT access and ANC counseling, nor looking at the programs of three of the big actors on global health whose work is evidence-based—Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Evidence Action, and J-PAL—returned any results. In general, there are quite a few results about family planning programs, such as the Lesotho Planned Parenthood Association. While they are unlikely to implement the exact intervention we research in this report, it could be that they include aspects of it, such as offering pregnancy testing (since health care providers might want to rule out pregnancy before providing women with hormonal contraception).

We expect that spending more time on this and using different search strategies, such as talking to experts, might yield more results on this front. However, we could not find any existing organizations in the field related to our intervention, so we left the column for this factor blank in the GWFM spreadsheet.

We decided to model the cost-effectiveness for a hypothetical intervention in India because it was in the top countries according to our GWFM. We didn’t have time to model the cost-effectiveness for any other country.

India has a network of CHWs stationed at villages, called ASHA workers or ”’accredited social health activists”, and another network of CHWs stationed at primary health sub-centers called ANMs, or “auxiliary nurse midwives” (Ashok et al., 2018). There are approximately 157,935 sub-centers in the country, each covering 5,662 people on average (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2022).

ASHA workers are responsible for, amongst other things, increasing health awareness and stocking condoms, iron tablets, disposable delivery kits (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2022), while ANMs are responsible for basic ailments, antenatal, postnatal, and delivery care (Ashok et al., 2018).

For the intervention, we assumed that we would train ASHA workers at their reporting sub-centers each year for as long as the charity operates (i.e. five years) and provide them with UPTs on an ongoing basis[19]. Each partner sub-center would receive training once a year. We assume the organization would scale linearly. Hence, we would hold training sessions at 20–1,600 sub-centers in the first year, twice as many in the second year, thrice as many in the third year, and so forth. The intervention would (potentially) impact the total women of reproductive age served by the partner sub-centers in any given year.

6.1 Effects

1. In order to model the effects of the intervention, we first estimated the number of women who could confirm whether or not they are pregnant without the intervention (counterfactual scenario) and the number of women who would be able to confirm whether or not they are pregnant with the intervention (intervention scenario). Thereby, we estimated the increase in women who could confirm whether or not they were pregnant due to the intervention.

This was estimated using the results from a RCT in Madagascar (Comfort et al., 2019) that found that providing CHWs with UPTs increased the number of women who sought out CWHs and the number of women who could confirm whether or not they were pregnant. The trial found that providing CHWs increased the number of women who sought out CHWs by 50% and increased the percentage of these women who knew whether or not they were pregnant by 86%[20]. For the baseline number of women seeking out CHWs in India, we used the number of women getting ANC counseling from CHWs as a very rough proxy for lack of a more accurate data source (National Family Health Survey results, as quoted by Nadella et al., 2021).

2. Following the above, we calculated the number of women who could confirm whether or not they were pregnant and were actually pregnant, by using the national pregnancy rate (i.e. the ratio of the number of pregnant women to the number of women of reproductive age in India). We adjusted the ratio for both the counterfactual and the intervention scenario, assuming that the rate of pregnancy would be higher amongst the women that seek out CHWs. With this, we calculated the difference in the number of pregnant women who could confirm their pregnancy due to the intervention.

3. Since we did not have adequate studies to extract a possible effect of CHWs’ counseling or UPT provision on ANC uptake, we used the national baseline rate of ANC access (40–49%, estimated from Mollar et al., 2017; the data from this paper was also used in the GWFM). We thus calculated the additional number of women who would receive ANC by multiplying this baseline rate by the number of pregnant women who could confirm their pregnancy earlier due to the intervention. In other words, we assumed that in both scenarios, 40–49% of all women who access CHWs and find out they are pregnant would seek out ANC (in the case of India, visit the ANMs at the primary health sub-centers for ANC)[21].

4. The consequent impact on neonatal mortality was estimated from an observational study that used DHS data from 1990 to 2013 to analyze nationally representative data of 69 LMICs and MICs (Kuhnt & Vollmer, 2017). Based on the study, we assumed that one ANC visit reduced neonatal mortality by 33% and that four visits reduced it by 51%. The 33 to 51% range is similar to the conclusions reached by other papers in section 3.2.1 of our evidence review. These effect sizes do not quantify the impact of early ANC, only the impact of one additional appointment to four minimum appointments (one being the minimum amongst women who, by definition, access ANC and four being the number that meets the minimum recommended number of appointments by the WHO). Moreover, according to most papers we reviewed, the impact of four visits typically includes the impact of having been attended to by a ‘skilled provider’.

5. Finally, we converted the number of neonatal deaths averted to the number of averted DALYs by using 33 DALYs per neonatal death. This was the same weight assigned by GiveWell (2020) to neonatal deaths due to syphilis. We also calculated the impact of the program over time, assuming the linear scaling mentioned at the beginning of this section. However, we did not include a time discount in our analysis for the sake of simplicity and because we only modeled the intervention for a five-year horizon.

6. Due to the limited and weak evidence used to calculate effects, we discounted our estimated impact by applying three discounts: a generalizability discount, certainty discount, and bias discount. Our CEA is extremely sensitive to these discounts.

6.2 Costs

We included the following costs in our model:

The costs of UPTs include shipping, delivery and the monetary incentive provided to CHWs (the latter is standard practice in India, see Government of India, 2020). The per unit cost of UPTs and the per unit incentive to ASHA workers were extracted from two separate sources, while the per unit delivery cost was estimated using Fermi estimates. UPTs are fairly inexpensive. The major uncertainty here was the delivery costs. Given that UPTs will be delivered to rural health clinics, costs for this could vary given how easily reachable these clinics are.

Costs of training of CHWs. The costs for training were estimated using Fermi estimation. The total cost was based on the number of trainers, the duration of the training and the number of training per year. All of these are estimates and can be adapted once the implementation of the intervention is planned in more detail.

Organizational costs and counterfactual costs of employees. These were provided by CE RTP team and are held constant for all CEAs conducted by CE.

Additionally, we assumed the cost for developing the training material would be in-house and included in organizational costs. We did not include the following costs due to time constraints: costs to beneficiaries, costs to government, opportunity costs of CHWs, discounts associated with government costs and costs borne by philanthropic actors.

6.3 Results and key uncertainties

Based on all of the above, our final estimates for the cost-effectiveness of this intervention in India is 98.3$/DALY (lower bound: 11.79$/DALY; upper bound: 819.60$/DALY).

Although our modeled intervention meets GiveWell’s cost-effectiveness bar of 100$ per averted DALY, we think our CEA is very speculative given that it is based on many estimates and imperfect proxies. The following factors could greatly change our cost-effectiveness estimate:

Our impact estimates do not affect neonatal/maternal health apart from reduced neonatal mortality. It also considered the monetary incentives provided to CHWs as costs while this can also be seen as an indirect benefit of income generation for CHWs who are women in the village. While we did not have time for a detailed sensitivity analysis, the point estimates in the CEA seem to be sensitive to these monetary benefits.

As mentioned in our evidence review, we were unable to find any study that directly estimated the impact of early pregnancy confirmation on ANC initiation and assumed that the baseline rate of health seeking behavior when it came to ANC remained the same. Our results were thus largely driven by the additional number of women who accessed CHWs and confirmed they were pregnant due to the intervention. These assumptions and estimates are somewhat arbitrary.

Our impact estimates also have 5-15% generalizability, bias and certainty discounts due to how context-specific this intervention is and the fact most intermediary outcomes are modeled based on one RCT. They do not include a time discount, for the sake of simplicity and because we only modeled the intervention for a 5 year horizon. Additionally, we have widened the confidence level on several of the point estimates used from studies we found in our evidence review, since we felt the results not be straightforwardly generalized.

It is also highly dependent on the scale of the charity’s operation. The above estimate assumes a linear expansion of 179 (lower/upper bound: 20, 1600) sub-centres per year. Reducing that to 77 (lower/upper bound: 20, 300) sub-centres reduces the cost-effectiveness to 141.61$/DALY (lower/upper bound: 24.7, 819.6).

7 Conclusion

In conclusion, we view dispensing UPTs to promote early ANC attendance as a low-evidenced but potentially cost-effective idea and do not recommend this intervention to be used for founding a new charity.

Our cost-effectiveness model of a hypothetical five-year program in India comes up with an estimate of 98.3$/DALY(lower/upper bound: 11.79–819.60$), with 38,530 averted DALYs in total (lower/upper bound: 3228–459,941). Although our modeled intervention meets GiveWell’s cost-effectiveness bar of 100$ per averted DALY, we think our CEA is very speculative given that it is based on many estimates and imperfect proxies which we are very uncertain about.

The evidence base for this intervention is very weak and it is unclear whether this intervention would have any impact. There are no studies looking at the effect of UPT provision on earlier ANC initiation, nor is there reliable and positive evidence on the effect on CHWs’ counseling on earlier ANC initiation. Additionally, we remain quite uncertain about many of the assumptions we made in our theory of change. The only causal link which we are certain about is the one between higher ANC attendance and decreased risk in neonatal mortality—however, this relies on the quality of provided ANC which is fairly low in many countries.

Given the strong link between increased ANC and risk of neonatal mortality, we think further research could look at ways to promote earlier ANC initiation that have a more robust evidence base, such as via mass media campaigns. Research on UPT provision and/or pregnancy confirmation and its effects on ANC would also be relevant, when based on a needs assessment in a given context.

The WHO (2016) recommends “pregnant women to have their first contact in the first 12 weeks’ gestation, with subsequent contacts taking place at 20, 26, 30, 34, 36, 38 and 40 weeks’ gestation.”

We also think it would be interesting to look at the effectiveness of radio campaigns in conjunction with the provision of urine pregnancy tests to CHWs. However, further consideration of this idea was out of scope of this report.

“Across regions, women were reported to often have a limited understanding on the purpose of early ANC and therefore the right time to seek care during pregnancy. This lack of understanding might be influenced by a perception that ANC is primarily provided to detect or treat diseases and was suggested to associate with women’s educational level literacy rate” (Gamberini et al., 2022).

“Sometimes it’s difficult to tell that you are pregnant. Some people have irregular periods, they miss periods for months only to find that they are not pregnant, so it’s better to wait, to see if you are really pregnant” (Myer & Harrison, 2003).

They found that women often delayed ANC due to uncertainty in their first trimester about their pregnancy status. Pregnancy tests were expensive and palpation at 12 weeks was used for pregnancy confirmation. Therefore, health staff typically advised women to begin ANC after they confirmed the pregnancy. This uncertainty intensified for women who had previously struggled with conception or maintaining a pregnancy. Many women started ANC after missing two menstrual cycles, but misconceptions about contraceptives leading to missed cycles sometimes caused delays (Pell et al., 2013).

“Some women, when they get pregnant, may not know that they are pregnant. They can go for months without knowing. So, when they start counting, they may be behind” (Mutowo et al., 2021).

“However, being knowledgeable of the signs of pregnancy appears to be associated with early initiation, while a lack of knowledge appears to be associated with late initiation [...]. Relatedly, unawareness of being pregnant proved a barrier [...] associated with late uptake of ANC [...]” (Grand-Guillaume-Perrenoud et al., 2021).

“Low knowledge of ANC was associated with higher odds of late ANC initiation [...] and inadequate ANC utilization [...]” (Grand-Guillaume-Perrenoud et al., 2021).

“Women’s health beliefs, specifically those who believed that ANC was beneficial, were more likely to use maternal health services compared to those who believed ANC was only for curative purposes. Additionally, many women believed that pregnancy is a natural process and care should only be sought if one becomes ill or develops complications [...]. Therefore, the type of health belief that a woman held regarding the utility of ANC played a role in whether or not they utilized it” (Alibhai et al., 2022).

“In developed countries, comparison of outcomes among women who did and did not receive antenatal care, or who first attended late vs. early in pregnancy have been shown to be confounded by socio-economic factors, education, unwanted pregnancy, maternal age and other factors that influence the outcome of pregnancy” (Carroli et al., 2001).

Study 4 presentes results in percentage point increases. When converted to percentage increases, the results show a 33% decrease in neonatal mortality for each additional ANC visit and 51% decrease in neonatal mortality for 4 ANC visits and a visit from a skilled provider. This is similar to the 32% and 55% range presented in study 5.

“This was one of the first trials adding the treatment of SAM to a CHW workload and suggests that adding SAM to a well-trained and supervised CHW’s workload, including preventive and curative tasks, does not necessarily yield lower quality of care. However, increased workloads had consequences for CHWs’ domestic life, and further increases in workload may not be possible without additional incentives” (Puett et al., 2012).

“Introduction of CCSPT was not very detrimental to pre-existing community services. CHWs managed their time ensuring additional efforts required for CCSPT were not at the expense of essential activities. The programming and policy implications are that multi-tasking CHWs with CCSPT will not have substantial opportunity costs” (Chinkhumba et al., 2022).

“CHWs in LMICs reported that they have a high workload; mainly related to having to manage multiple tasks and the lack of transport to access households. Program managers need to make careful consideration when additional tasks are shifted to CHWs and the practicability to be performed in the environment they work in. Further research is also required to make a comprehensive measure of the workload of CHWs in LMICs” (Astale et al., 2023).

We haven’t considered the exact delivery mechanism but assume that the UPTs would also be delivered to the sub-centers where training is held and distributed to the ASHA workers reporting at those.

The study was unclear on whether the 86% represented the increase in women who confirmed they were actually pregnant or increase in women who confirmed whether or not they were pregnant. We assumed it to be the latter because an 86% confirmation rate in favor of pregnancy seemed high.

Based on our evidence review, we conclude that CHWs counseling on the importance of ANC has no effect on ANC uptake and the additional ANC uptake is solely due to the additional number of women who seek out CHWs and confirm they are pregnant.

Intervention Report: Dispensing Urine Pregnancy Tests to Promote Early Antenatal Care Attendance

This report was conducted within the pilot for Charity Entrepreneurship’s Research Training Program in the fall of 2023 and took around eighty hours to complete (roughly translating into two weeks of work). It also was the first intervention report we ever wrote and we would do several things differently in hindsight. Please interpret the confidence of the conclusions of this report with those points in mind. Please also note that the intervention was assigned to us for this report.

For questions about the research process, please contact Leonie Falk at leonie@charityentrepreneurship.com. For questions about the content of this research, please contact Helene or Priyanshadirectly.

The full report can also be accessed as a PDF here.

Thanks to Leonie Falk and Filip Múrar for their review and feedback. We are also grateful to the experts who took the time to offer their thoughts on this research.

Executive summary

Every year, 2.4 million babies still die within a month after their birth. Antenatal care (ANC), which includes all kinds of health services for pregnant women, plays an essential role in reducing neonatal mortality, yet many pregnant women do not attend ANC or start attending too late in their pregnancy in order to receive appropriate care. Two barriers to attending are women not knowing they are pregnant until they are already far along in their pregnancy, and not being aware about the importance and benefits of ANC.

To overcome these two barriers, the intervention in this report focuses on dispensing free urine pregnancy tests (UPTs) at the community level so that women who suspect they are pregnant are able to confirm their pregnancy. The intervention is paired with counseling on when and how to use UPTs, the importance and benefits of (early and frequent) ANC attendance, as well as how and where ANC can be accessed so women are more likely to use these tests and have their first ANC visit in their first trimester once they confirmed their pregnancy.

The evidence base for this intervention is very weak and it is unclear whether in practice this intervention would have any impact. There are no studies looking at the effect of UPT provision on earlier ANC initiation, nor is there reliable and positive evidence on the effect on CHWs’ counseling on earlier ANC initiation. Additionally, we remain quite uncertain about many of the assumptions we made in our theory of change. The only causal link which we are certain about is the one between higher ANC attendance and decreased risk in neonatal mortality—however, this relies on the quality of provided ANC, which is fairly low in many countries.

Our cost-effectiveness model of a hypothetical five-year program in India comes up with an estimate of 98.30$/DALY (lower/upper bound: 11.80–819.60$), with 38,530 averted DALYs in total (lower/upper bound: 3,228–459,941). Although our modeled intervention meets GiveWell’s cost-effectiveness bar of 100$ per averted DALY, we think our CEA is very speculative given that it is based on many estimates and imperfect proxies which we are very uncertain about.

Overall, we conclude this is a potentially cost-effective intervention but has extremely little evidence, thus we do not recommend this intervention to be used for founding a new charity.

1 Background

1.1 Burden of disease

Neonatal mortality continues to present a critical challenge in public health, particularly in low- and lower-middle-income countries. Neonatal deaths—those occurring within the first 28 days of life—make up around 47% of all under-five child deaths, totaling about 2.4 million worldwide (WHO, 2020).

Figure 1: Number of child deaths by region (Roser et al., 2013)

1.2 Antenatal care