Shrimp Paste and Animal Welfare

Shrimp Welfare Project (SWP) produced this report because we believe it could have significant informational value to the movement, rather than because we anticipate SWP directly working on a shrimp paste intervention in the future. We think a new project focused on shrimp paste could potentially be very high impact and would be excited to collaborate with organizations working in this space.

This report was written by Alethea Faye Cendaña and Trinh Lien-Huong, with feedback provided by Shannon Davis, Aaron Boddy, Michael St Jules, Ren Ryba, and Zuzana Šperlová. We are grateful to all the stakeholders who took the time to offer their thoughts for this study. We would like to thank the external reviewers for their valuable insights and contributions. All errors and shortcomings are our own.

Executive Summary

Acetes shrimps are among the most — if not the most — utilized species for food globally. Harvested from the coastal regions of Asian countries, these shrimps are not only cooked into various dishes but also crucial in the production of shrimp paste: a salty, tangy condiment served in many Southeast Asian dishes.

Despite the enormous scale of production, there’s scarce information about the shrimp paste industry and its impact on Acetes shrimp welfare. Thus, it is crucial to explore and understand the industry to identify and implement welfare interventions effectively. This report discusses an overview of the shrimp paste industry and highlights welfare issues and challenges to determine opportunities for welfare interventions. We take Vietnam, one of the largest producers, as a case study to gain a deeper understanding of the industry

Shrimp paste is an integral condiment for Southeast Asian cuisine, valued for its unique umami flavor and nutritional properties, including vital omega-3 fatty acids. The production process primarily involves sun-drying, grinding, and fermenting Acetes shrimps, which varies in duration and technique across countries. While deeply rooted in cultural heritage and social practices, shrimp paste is also a significant commercial product, with villages selling locally and countries like the US, UK, Canada, and Australia importing from top-producing countries like Thailand and Indonesia.

The industry provides livelihood opportunities for small coastal communities, where activities are divided among families with roles in catching, trading, and processing. Manufacturing facilities with capital, usually located near coasts, employ manual labor to mix, ferment, and cook the shrimp paste before packaging it for commercial sale. All producers face significant issues in raw material supply due to their reliance on natural shrimp stocks. These stocks are subject to fluctuations and environmental threats. Moreover, there are additional challenges related to food wastage, as well as food hygiene and safety concerns in both traditional and commercial production methods.

Acetes shrimps are likely to endure significant suffering throughout the capture, retrieval, and processing stages in shrimp paste production. They experience injury, exhaustion, and suffocation during capture, often dying from hypoxia due to overcrowding or suffocation when removed from water. Additionally, during processing, they could suffer from osmotic shock, dehydration, and stress due to salting, grinding, and sun-drying, which are methods used to prepare them for paste production.

Our Vietnam case study explores the fishing practices, the economic and cultural importance of shrimp paste, and the operational dynamics and challenges of small communities and large companies involved in the industry.

We propose interventions to alleviate the suffering of Acetes shrimps, such as gentler capture methods and humane slaughter practices. Developing vegan versions could be promising to reduce reliance on wild-caught Acetes shrimps. Innovations to address challenges in market accessibility, cost, and achieving the desired gastronomic qualities are important to the success of any potential alternative.

This scoping study provides foundational information on the suffering of Acetes shrimps harvested for the shrimp paste industry. Further research on Acetes shrimp sentience, the shrimp paste industry, and customers is needed to develop specific and effective solutions.

Introduction

Shrimps are the most commonly utilized aquatic animals in the world. However, there is burgeoning evidence that decapods like shrimps might be sentient (Shrimp Welfare Project, n.d.) and, thus, may be aware of the suffering they go through as they are caught and killed for human consumption.

Acetes shrimps, mostly the A. japonicus species, are tiny shrimps captured in the coastal regions of India, Korea, Japan, China, and other Southeast Asian countries where they are turned into shrimp paste. According to Rethink Priorities’ estimate, 4.1 to 55 trillion individual A. japonicus shrimps were captured in 2020 (Waldhorn & Autric, 2023). This outnumbers the sum of all vertebrate animals farmed for food globally, making A. japonicus one of the most utilized species for food production.

Shrimp paste is a region-specific food product, yet it could impact the welfare and well-being of many aquatic animals. Furthermore, very little information is available about the industry, such as shrimp quantities processed, socioeconomic influences, and welfare impacts. Therefore, this study aims to:

Provide an overview of the shrimp paste industry and identify the welfare issues and challenges surrounding it;

Determine opportunities for welfare interventions; and

Provide a case study on one of the top-producing countries to further examine and understand the industry.

Global overview of the shrimp paste industry

Shrimp paste is a traditional Southeast Asian condiment that originated from the Cham and Mon people of Indo-China (Indochina) and eventually spread to the entire region. It is an essential ingredient for many meals due to its rich umami flavor and nutritional value (Pamungkaningtyas, 2023). Each Southeast Asian country has its own production process, name, and dedicated uses for shrimp paste based on their cultural preferences and practices.

Use

In general, shrimp paste plays a vital role in Southeast Asian cuisine and diet. Shrimp and fish condiments are found to have measurable quantities of polyunsaturated fatty acids such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which is an omega-3 fatty acid suitable for the heart and needed by the brain (Aung et al., 2004). Thus, shrimp paste is regarded as a low-cost source of dietary protein when consumed with raw vegetables, edible leaves, and rice. It is also used as a dipping sauce for meat and seafood for what many consider to be an elevated eating experience.

Shrimp paste can come in three types of consistency: the first is extremely dry and firm; the second is a thick fluid; and the third is watery—depending on the salt level and the sun drying process. The first can be used to marinate food, while the latter two types can be used both as dipping sauce or seasonings.

The color, consistency, texture, and taste of the condiment differ in each country. Table 1 below summarizes some of the unique uses per country and their physical characteristics and appearance.

| Country | Local Name | Uses | Physical Appearance |

| Indonesia | Terasi | Terasi-udang is often mixed with chili, garlic, and salt to create sambal-terasi, a condiment added to rice meals, snacks, vegetables, and fruit dishes. | A semi-solid paste with a red brownish color |

| Malaysia | Belacan | Belacan is usually mixed with chilies and limes to create the famous Malaysian condiment called sambal-belacan (Hajeb & Jinap, 2012). One to two teaspoonful of this is typically added to dishes to boost their flavor. It can also be enjoyed directly with rice. | A semi-solid paste with a red brownish colour Sara Khong (2019) |

| Philippines | Alamang | Alamang is often consumed raw or cooked as a condiment with meat, vegetables, or fruits (Hajeb & Jinap, 2012). This ingredient is also frequently incorporated as an extra flavor enhancer in various Filipino dishes. | Thick paste with pinkish color Picture from Agatha Gregorio (2021) |

| Thailand | Kapi | Thai meals are never complete without nahm prik, hot and spicy dipping sauces for vegetables and fish with shrimp paste as the main ingredient. Belacan-kapi, which is kapi mixed with chili, is also a favourite condiment in Thailand (Hajeb & Jinap, 2012). | A semi-solid paste with a pinkish or purplish grey color Picture from Shayne Chammavanijakul (2022) |

| Vietnam | Mam tom Mam tep Mam ruoc | In Vietnam, shrimp paste is used as a dipping sauce for boiled meat, tofu, and boiled vegetables. It is also added to broth dishes. | A thick paste or liquid sauce with pinkish color Picture from VinWonders (2022) |

| Table 1. Uses and physical appearance of shrimp paste in Southeast Asian countries | |||

Aside from culinary purposes, shrimp paste is also deeply embedded in cultural heritage and social practices. The Indonesian term, terasi is believed to be derived from “asih,” which means admiration, and combined with “ter,” which means most; resulting in a word that means most admired (Surya et al., 2023). In Malaysia, belacan represents diversity as each state has its version of the paste. It is also a highly-regarded gift from the Malaysian royal family to its neighboring countries, such as Singapore. In the Philippines, making and sharing shrimp-paste based condiments is a communal activity during festivals or special occasions (Aster et al., 2023).

Production

Acetes is the most common genus used in its raw form in shrimp paste production. Acetes are shrimps that prefer the environment just below the ocean’s surface up to approximately a depth of 100 meters. They are usually found in bays and tend to aggregate in the surface layer of the sea, making it easy to catch vast numbers of them at once.

The harvesting of wild Acetes shrimps is usually carried out during their months of occurrence and abundance in coastal areas (Deshmukh, 1991). Different species of Acetes shrimps are used depending on their availability in each country. Table 2 lists the Acetes species used in Southeast Asian countries in 1990 (Hajeb & Jinap, 2012). The most commonly used species are A. indicus, A. erythraeus, A. vulgaris and A. japonicus.

| Country | A. erythraeus | A. indicus | A. intermedius | A. japonicus | A. sibogaesibogae | A. vulgaris |

| Indonesia | x | x | ||||

| Malaysia | x | x | x | |||

| Myanmar | x | x | x | |||

| Philippines | x | x | x | |||

| Singapore | x | x | x | |||

| Thailand | x | |||||

| Vietnam | x | |||||

| Table 2. Acetes species used in shrimp paste production in Asian countries (Hajeb & Jinap, 2012) | ||||||

The production of shrimp paste generally involves three processes: (1) sun-drying, (2) grinding, and (3) fermentation. Salt is added during sun-drying or grinding to prevent food deterioration and enhance flavor.

Freshly caught shrimps are initially exposed to direct sunlight to kill microorganisms and increase shelf life by reducing their moisture content. Sun-drying typically takes 4-24 hours depending on the preferred paste consistency (semi-solid or liquid). In Malaysia and Indonesia, the process takes up to 24 hours and is done in multiple batches to achieve a semi-solid product, while in the Philippines and Vietnam, the shrimp are dried briefly as those countries prefer a more liquid paste.

The shrimps are ground using a mortar and pestle (or sometimes by human feet) for a smoother consistency. The dried ground shrimp is left to be fermented inside a container (usually a deep jar) to produce short-chain peptides and free amino acids that give the paste its umami flavor. The fermentation process typically spans from a few days to a few months, depending on the desired aroma and flavor of the paste. Table 3 details the different processes for shrimp paste production across Southeast Asia (Pamungkaningtyas, 2023).

| Country of origin | Shrimp paste | Process and conditions |

| Cambodia/Thailand | Kapi | Main species: krill (Acetes vulgaris or Mesopodopsis orientalis)

|

| Indonesia | Terasi | Main species: Planktonous shrimp (Schizopodes or Mytis sp.)

|

| Malaysia | Belacan | Main species: krill/caught in sea water

|

| Myanmar | Ngapi | Main species: Mysis sp. Shrimps washed, mixed with salt

|

| Philippines | Bagoong-alamang | Main species: Atya sp. or Acetes sp.

|

| Vietnam | Mam tom Mam tep Mam ruoc | Main species: Acetes japonicus

|

| Table 3. Shrimp paste production in Southeast Asian countries | ||

Shrimp paste, typically produced by fishing families in coastal villages, is often sold and consumed locally. Additionally, some of this paste is transported by vendors to nearby towns, particularly those without their own fishing villages. Acetes shrimps not being sold/consumed locally are immediately sold to middlemen and distributors who process and sell commercialized shrimp paste (National Research Council, 1992).

There are a few countries, such as the US, UK, Canada, and Australia, that import shrimp paste from top exporters, such as Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines. The demand usually comes from immigrants from the exporting countries who buy Asian spices and products from Asian specialty stores.

Supply chain

Small producing communities

The commercial utilization of A. japonicus has thrived throughout the years and has been an important source of livelihood for small villages in coastal areas. For example, in the Philippines, 500 families in a town called Tigbauan depend on the industry (Iguban et al., 2017). These households are employed throughout the supply chain in roles such as catching, raw shrimp trading, processing, and processed shrimp trading.

Below is a diagram of the shrimp paste supply chain in two coastal municipalities in the Philippines (Iguban et al., 2017). This seems to be representative of the model for shrimp paste sold in informal markets.

| Figure 1. Supply chain of Acetes shrimp in Oton and Tigbauan Philippines adapted from Iguban et al., 2017 |

Traditionally, shrimp catching is male-dominated, as they are perceived to have stronger muscle power, more endurance, and more stamina which is required in setting up nets and carrying boxes to load and unload shrimps. In the Philippines, raw shrimp traders are mostly female since they are considered to have better negotiation skills. They purchase from shrimp catchers and sell to retailers in nearby villages/barangays (the smallest administrative division in the Philippines, akin to a village) and municipalities. Some also deliver to restaurants and food establishments in cities up to 20 km away.

Equipment used

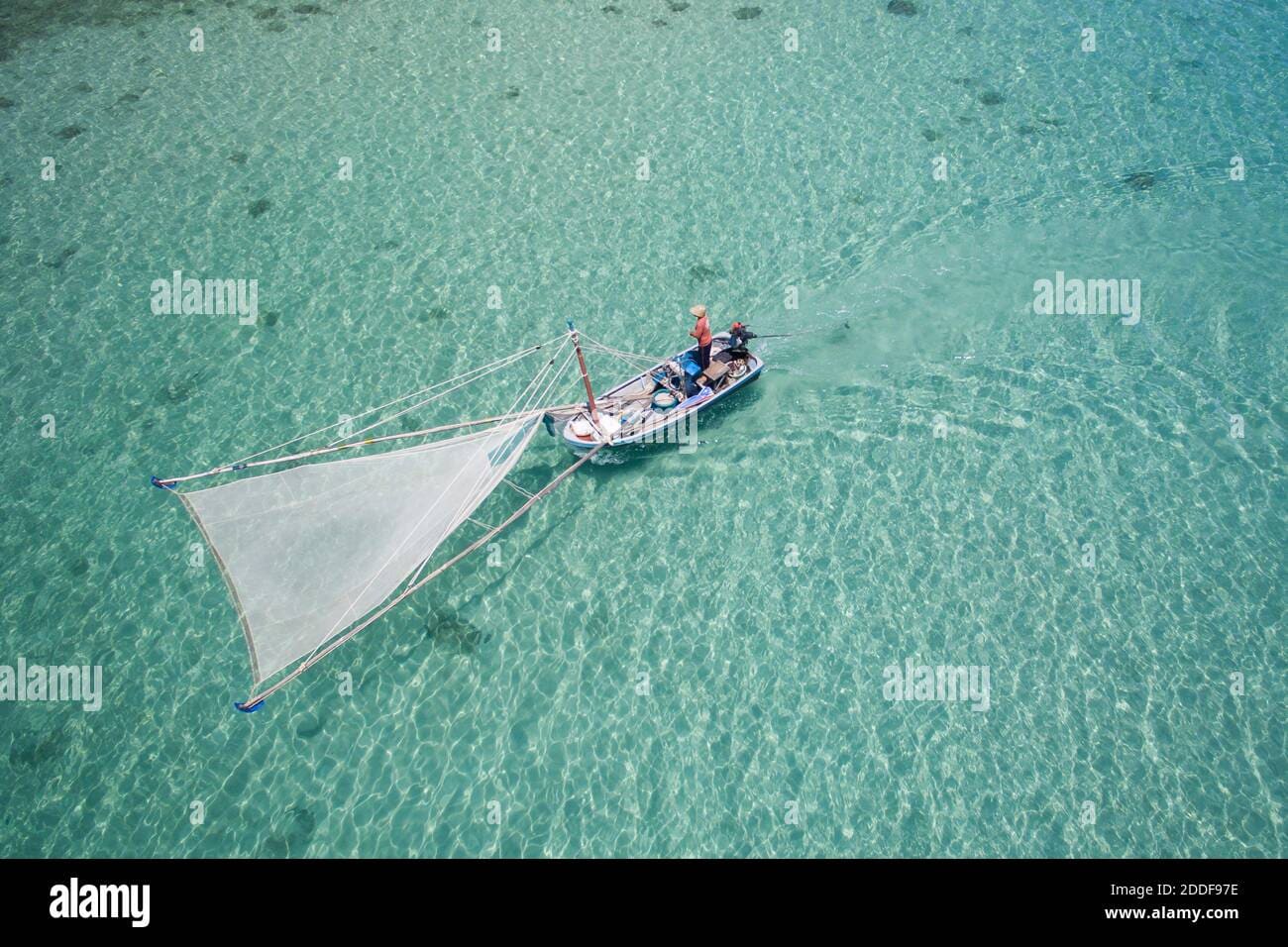

Shrimp catchers use two main gears: a filter bag net (called a saluran or tangab in Filipino), and a motor-operated skimming net. Filter bag nets are stationary nets that are set or moved against the currents. Skimming nets are active fishing gear with a big triangular net and a motor-driven boat. Higher tides typically result in bigger harvests when using filter bag nets. On the other hand, it is not preferable to use a motor-operated skimming net under bad weather conditions.

| Figure 2. Pictures and illustration of a saluran or filter stationary net with wings used to trap Acetes shrimps in estuaries: (a) One filter net setup, (b) A series of filter nets interconnected by bamboo bridges often owned by one fisherman, (c) Parts of a saluran; the wings provide additional stability, the net mouth allows entry of shrimps, the net body sieves the water column to capture the shrimp, and the cod end is where the shrimps are retained (Monteclaro et al., 2017) | |

| |

| Figure 3. Pictures and illustration of a shallow-water tangab or non-winged type filter net or stow net used to trap Acetes shrimps in estuaries: (a) One shallow-water tangab. Fishermen can easily uproot the bamboo posts to transfer the setup to areas with abundant shrimp (b) Parts of a tangab; the posts act as pillars that ensure the mouth of the net is properly opened, the net mouth spans from the seafloor to the surface and lets shrimps enter, the net body sieves the water column, and the cod end is where the shrimps are trapped (Monteclaro et al., 2017) | |

|  |

| Figure 4. (a) A motor-operated skimming net operated in Iloilo, Philippines (Bagarinao & Recente, n.d.) and (b) the aerial view of the same gear type in Thailand (Milnes, 2017) | |

Shrimp paste manufacturers

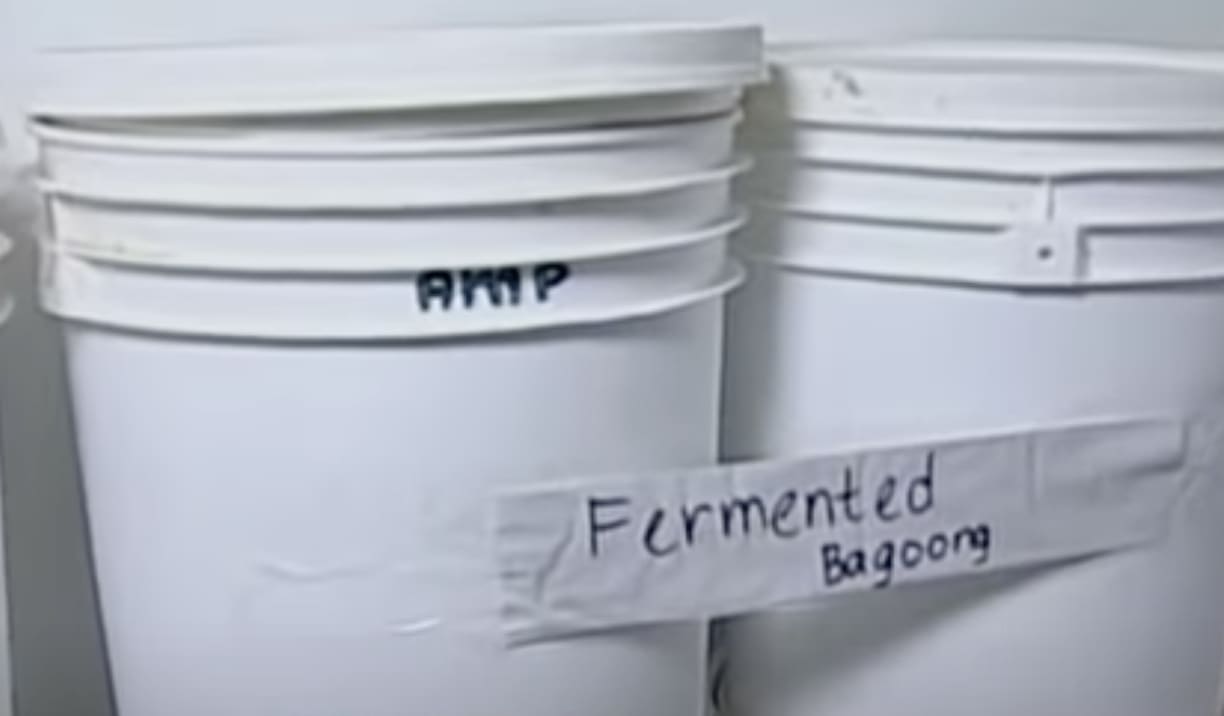

Shrimp paste sold in supermarkets is usually produced in manufacturing facilities that hire workers to manually mix salt with the Acetes shrimps before fermentation. For the case of the manufacturer in the Philippines shown in the pictures below, instead of ceramic jars, the shrimps are stored in plastic buckets for at least three days. The fermented batches are sorted by hand to remove the small fish and shells to achieve a uniform quality. After processing, the shrimp paste is cooked in different flavors, such as spicy, garlic, and sweet, and then packed in a jar (GMA Public Affairs, 2019).

|  |

|  |

| Figure 5. Pictures from a shrimp paste manufacturing facility in the Philippines; (a) shrimps are sorted to remove by-catch and stones, (b) batches fermented in plastic buckets, (c) the shrimp paste is cooked with garlic, oil, salt, and sugar to produce a flavored commercial product, (d) filling of glass bottles with the cooked shrimp paste (GMA Public Affairs, 2019) | |

Some manufacturing facilities are situated near coastal areas. They usually buy freshly caught shrimps from fishermen, which are brought straight to the factory.

Issues in the industry

The shrimp paste industry is fairly small and informal, which makes it susceptible to different challenges. There is a limited number of producers and it has a very niche market that is widely unregulated.

The first challenge is its high dependence on the variable population of the stock in nature (Nugraha et al., 2017). Acetes shrimp catchers usually operate in months when shrimps are abundant in the coastal areas, which leads to downtimes during off-peak months when shrimp populations are low. Shrimp populations are influenced by their fluctuating migration patterns and unpredictable climate conditions.This variability results in frequent disruptions to the business, which make it difficult to have predictability and stability.

In the past, the industry has also threatened mangrove biodiversity as local people in villages near mangroves fish for Acetes shrimp in these areas (Macintosh et al., 2002).

| Figure 6. A Thai local fishing for Acetes shrimp in front of a mangrove area (Macintosh et al., 2002) |

Conversion of coastal areas into commercialized beaches also threatens the industry, especially the small producing communities. Increased human activities displace Acetes shrimps from their natural habitats. Furthermore, commercial development can cause the local community to be prohibited from conducting their usual production or even forced to relocate their homes (FEATR, 2023).

|

| Figure 7. A scenic beach area in Guimaras, Philippines where the small community depends on shrimp paste for livelihood. A private individual has purchased their town and plans to turn it into a resort (FEATR, 2023). |

Another issue, which was observed often in the Philippines, is food waste. Since shrimp paste has a strong flavor and high sodium levels, people usually do not consume large quantities per meal. Fresh shrimp paste is usually stored in bulk and kept in the refrigerator or at room temperature for anywhere between 6-12 months.. After a few months, the smell and taste of shrimp paste becomes undesirable, and people often prefer to buy fresh shrimp paste. Many sellers in informal markets also need to regularly dispose of older, unsold shrimp paste since consumers tend to prefer fresh.

Food hygiene and safety are also big concerns for both commercially and traditionally produced shrimp paste. In general, commercially sold shrimp paste should follow laws on Food Safety, such as in Vietnam (National Assembly of Vietnam, 2010) and in the Philippines (Food Development Center, 2013). Furthermore, for the Philippines, consumers are warned by the Food and Drugs Administration not to purchase unregistered shrimp paste products as their quality and safety have not been evaluated (FDA Philippines, 2023).

However, there are instances when shrimp paste products are still sold without strict compliance. One concern among consumers revolves around the method of mixing and massaging shrimp paste by foot, which is viewed as unhygienic (FEATR, 2023). In manufacturing facilities, foreign objects or small animals such as insects or lizards can get mixed into the paste and go undetected since the paste is often homogenous and has a strong smell (Lang & Tam, 2017).

|  |

| Figure 8. Hygienic concerns with shrimp paste processing; (a) a fisherman in Iloilo, Philippines grounding shrimps as part of making bagoong the traditional way (FEATR, 2023) (b) a lizard corpse found in a shrimp paste tank in a manufacturing facility in Thanh Hoa (Lang & Tam, 2017) | |

Welfare issues

Unlike other wild-caught fish species, much is unknown about the suffering that Acetes shrimps experience from capture to processing.

Capture and retrieval

Acetes shrimps caught through stationary nets and motor-operated skimming nets likely experience suffering or death during the capture and retrieval process. The shrimps can get caught in the net for hours and are densely crowded. They can sustain injuries and become exhausted while struggling to wiggle out of the net, while also having the weight of other shrimps pressing against them. When they are taken out of the water, any shrimps still alive likely die of asphyxiation as their gills dry out and they are unable to extract oxygen from the air.

Another issue related to capture and retrieval is by-catch. Small fishes and shellfish are usually caught unintentionally but unavoidably in the net. Some of them are as small as the Acetes shrimps and are typically noticed and removed after the fermentation process. Sometimes, they are mixed and grounded and become part of the paste.

| Figure 9. By-catch of tangab fishery (stationary on-winged type net) in Iloilo, Philippines (Bagarinao & Recente, n.d.). Tangab catches generally have equal amounts of ‘good fish’ and ‘trash fish’. ‘Good fish’ are sold in the neighborhood while ‘trash fish’ are sun-dried for human consumption and the undesirable species are used in fishmeal production. |

Processing

If the shrimps do not die from suffocation or other stress during capture, they may suffer during the paste production. Depending on the nature of processing, they might first be salted, grounded, or sun-dried while still alive, though likely very few shrimp survive up to this point.

Shrimps, like other crustaceans and fishes, are accustomed to optimal salinity ranges in freshwater or saltwater habitats. When transferred to salinity levels outside the range, they typically experience osmotic shock, which is the stress that occurs when there is a sudden change in the salinity around their cells. This leads to a rapid movement of water across the shrimps’ cell membranes. When the shrimps are salted, their bodies will respond such that water will rapidly flow out of their cells to balance the salt concentration outside and inside. This causes their cells to shrink, which typically results in dehydration, impaired physiological functions, and death. In the case of Acetes shrimps, the outcome is fatal but not instant, and they first undergo stress due to osmotic shock.

The main purpose of sun-drying is to evaporate water from the shrimp’s body. This process dries out the shrimps’ cells while they are still alive.

In some countries, such as the Philippines, freshly caught shrimps are laid out underneath the sun and mixed uniformly with salt by hand. For big manufacturers, salt is added directly and put in a tub to begin the fermentation immediately. In some shrimp paste recipes, such as in Vietnam, the shrimps are ground and mixed with salt before sun-drying or fermentation.

Vietnam Case Study

Vietnam is one the countries that produce and export high volumes of shrimp paste in Southeast Asia, and their industry is well-documented. Shrimp paste is a significant commodity and food export for the country.

Last December 2023, shrimp paste was included by the country’s Ministry of Industry and Trade in its “One Commune, One Product” (OCOP) program (Van, 2023). The OCOP program seeks to promote Vietnam’s internal resources, such as raw materials or local culture/labor to increase their product value and contribute to rural economic development. New products are created and old products are improved through science and technology to meet local and international needs (Nguyen, n.d.). The inclusion of shrimp paste in the OCOP program not only emphasizes its cultural significance as a staple ingredient in Vietnamese cuisine but also highlights its potential to contribute to rural economic development.

Given the scope of this report, Vietnam was chosen as a country to examine in-depth through a case study, focusing on identifying and detailing the unique challenges within their shrimp paste industry.

Industry overview

The sea is considered by Vietnamese fishermen as “a blessing from heaven” (Thuy & Quang, 2023). In Thanh Hoa, a province in northern Vietnam, one of their most valued commodities is the small Acetes japonicus shrimp. The wild-caught shrimps are typically processed into various dishes, such as stir-fried shrimp, sour soup, and shrimp paste.

The Acetes japonicus fishing season in Thanh Hoa begins at the end of May and lasts until the end of October. If the weather is favorable, the season comes early. A. japonicus typically appears on cloudy days.

Between 3-5 in the morning, the beaches are crowded with rafts and basketboats used to catch A. japonicus shrimps. Each commune — a cluster of villages managed by a local council — has about 100 year-round rafts for seasonal fishing. Since the shrimps live near the shore, the rafts only travel 1-2 nautical miles to catch them. Each trip (going out to the sea and returning) takes about 3 hours. Each raft can make an average of 4-5 trips per day (K. Tuan, 2019).

|  |

| Figure 10. Shrimp-catching rafts operated by at least two people in Quang Hai Commune in Quang Xuong district in Thanh Hoa (Hoàng, 2023) | |

To determine an A. japonicus fishing area, the fishermen drop a small bag into the water and travel around. If there are A. japonicus shrimps in the bag when they pull up, they will put down the nets to catch more. After around two hours, the net containing the catch is hauled onboard and transported to the mainland for unloading.

As soon as the raft returns to the shore, the shrimps are bought at an average price of 7,000-10,000 VND or $0.29-$0.41 per kilogram. These are very good prices for fishermen. The average monthly income in rural areas is around 4 million VND or around $160 (General Statistics Office, 2023). Each raft typically catches 2-3 quintals (1 quintal = 100 kg), rendering profits of several million VND per day for fishermen (Hoàng, 2023).

|  |

| Figure 12. On the shores of Tien Trang beach, the caught shrimps by the fishermen are bought immediately by traders to be sold to processors or in markets (Hoàng, 2023) | |

| Figure 13. The trading scenes in Hoang Truong and Hoang Thanh communes of Hoang Hoa district: (a) people buying for trading or household consumption, (b) a fisherwoman bringing the shrimps to the shore, (c) shrimps bought by traders waiting for transportation (d) buyers negotiating with a trader (Minh, 2017) | |

According to Mr. Pham Van Hoan, the owner of a shrimp processing and purchasing facility in Quang Hai, the purchased Acetes shrimps are sold at markets in the province. Large quantities are also processed into dry dishes and condiments. The shrimps are immediately dried in the sun or processed as they would become mushy and unusable after two hours post-catching.

Some fishermen prefer drying the shrimps first before selling them. The price of dried shrimps is about 45000-50000 VND/kg (Hoàng, 2023). Based on rough calculations of people in fishing communities, the earnings from 10 kg of fresh A. japonicus is equivalent to the earnings from 3 kg of dried A. japonicus shrimps (Tuan M., 2023).

Interview with a fisherwoman from Thanh Hoa

We interviewed a fisherwoman from the Sam Son district of Thanh Hoa. She answered a few of our questions based on her experience of observing neighbors who fished Acetes and produced shrimp paste commercially. She does not fish Acetes but purchases from her neighbors to make shrimp paste for home use. She also mentioned buying shrimps on the shore when they were just pulled up from the sea.

She informed us that the daily production varies per day from 5 to 100 tons. The shrimp paste producers maintain a ratio of 5 baskets of shrimps to a basket of salt. She and her neighbors mostly used shrimps to make mam tep (a dish made by adding powdered grilled rice to harder-shelled shrimps). Mam tom (smoother in texture) takes more effort to make.

In the Sam Son district, the Bac Son and Trung Son communes are the major Acetes fishing areas. In these communes, people are semi-fishery farmers (wild fishery and vegetable farming) and depend on tourism for their livelihood. Fishermen catching Acetes shrimps usually fish from morning to noon and use drag nets. On the shore, fishermen sell directly to companies or to people who make shrimp paste. They also sell to tourists or wholesale to companies.

September to October is the primary fishing season for Acetes because their shells are hard, making them ideal for processing into dried goods. Meanwhile, from July to August, the shells of Acetes are soft, which makes them suitable for shrimp paste. When Acetes are out of season, they will catch another species.

The fisherwoman said that typically the Acetes shrimps are dead when they are brought ashore; they are so fragile that they are already dead after being lifted off the water and landing on the boat. She was not able to share about the socio-economic challenges of the shrimp paste makers and Acetes catchers as she was not that involved.

Large company processors

Large companies such as the Hoan Thanh Seafood Company Limited Hoa invest in building kilns to dry the shrimps. These have a capacity of 30-40 tons/day and can perform the job regardless of weather. In 2022, the company exports to China, Korea, Japan, and Malaysia, earning billions of dong (~$40,000) per year (Hai, 2022).

| Figure 14. Mr. Pham Van Hoan, owner of Hoan Thanh Seafood Company Limited Hoa, a shrimp processing and purchasing facility in Quang Hai commune (Hai, 2022) |

The company acquires its shrimps by buying freshly caught products from fishermen on shore. The shrimps are cleaned with fresh water and divided into two types: export quality and the remainder for shrimp paste. The export quality shrimps are processed for use in dried and wet products, with most of the wet products being exported to countries like Korea, where it is consumed with kimchi. In 2022, the company has over 40 processing workers and 80 fishermen partners, each expected to have an average income of 8-12 million VND or $300-$500 per month.

Challenges

Fishing for A. japonicus also comes with hardships. A fisherman from the Tien Trang commune described the job as dependent on luck. There were bad days when he went out rafting and came back with broken machines, broken nets, and minimal harvest (K. Tuan, 2019). He proceeded to confide (translated to English): “When there’s a good harvest, we smile, when there’s a bad harvest, we cry, but we love the sea and our job, so for generations, people here have had to cling to it no matter what.” A fisherman from the Hoang Thanh commune mentioned that when the A. japonicus season comes later than usual, most fishermen focus on other sources of income.

Furthermore, the job is very difficult and laborious. It typically requires two people on each raft who will make 4-5 trips on the beach per day, each lasting 2-3 hours. They do this under the intense heat of the sun with temperatures that range from 35℃ to 42℃. Despite the grueling trips and the hot weather, the fishermen regard the income as quite good, with each raft earning 1-1.5 million VND or $40-$60 profit per day, and on really good days, 2-3 million VND or $80-$120. The monthly income per capita in 2022 was 4.67 million VND which is around $190 (General Statistics Office, 2023).

The COVID-19 pandemic also had an impact on the export of dried A. japonicus, with one company reporting a 3-4 time decrease in revenue from exports (Hai, 2022). Domestic markets were also impacted, prompting them to offer products on e-commerce platforms. By 2022, the traditional markets had reopened.

Another reported issue for the shrimp paste industry in Vietnam is food and hygiene safety concerns. In 2017, there was a published article and video of an investigation of a large-scale shrimp paste production facility in Ngu Loc commune in Thanh Hao that processed and sold tons of shrimp paste every month (Lang & Tam, 2017). Buckets of shrimp paste were placed on the ground beside dustpans and plastic brooms. The workers pumped the shrimp paste into plastic containers with bare hands and bare feet. The soaking tank was made of dirty concrete, filled with a few pieces of plastic, nylon, and a moldy fibro cement cover. The tank was found to have maggots. There were lizards and cockroaches, both alive and rotting, floating in the shrimp and fish sauce. Despite this, the facility had legal documents certifying proper food hygiene and safety practices. This included a claim that they did not use any chemical additives, which was false, according to a worker who specialized in cooking additives and colorants for the facility. She mentioned using an amniotic red colorant to achieve a dark to light pink color. This releases a pungent smell when cooked, which requires gloves and masks because the fumes make it difficult to breathe. They only added the chemicals before bottling and selling, so the sample from the processing tank would incur no violations.

|  |

|  |

|  |

| Figure 15. Food safety and hygiene issues identified in certain manufacturing facilities in Vietnam: (a) maggots and spider corpse (Lang & Tam, 2017) and (b) lizard corpse in the mixing tank, (c) dirty concrete tank with mixing stick (Food and Health, 2021), (d) fermentation tub with dirty rims, (e) and (f) unhygienic bottling of shrimp paste products (VTV24, 2017) | |

Opportunities for intervention

To improve the welfare of the Acetes species, the following interventions in the value chain and alternatives to shrimp paste can be considered.

In the supply chain

A capture method should be designed such that the shrimps experience minimal levels of injury, stress, and mortality. In order to successfully develop this, a deeper investigation into how Acetes shrimps are captured must be carried out to determine the following:

The duration of time shrimp spend in motor-driven and stationary nets

Net volume and stocking density that doesn’t overly crowd shrimps

Optimal depth for capture such that the shrimps will not experience abrupt changes in water pressure or temperature and will not take a long time to land

It is also important to use knotless nets made of soft material to lessen physical injuries or stress to shrimps.

Commercial shrimp paste manufacturers can also be approached to implement higher welfare and humane slaughter practices.

Other promising interventions for improving wild-caught Acetes shrimp welfare are also discussed by (Ryba et al., 2023).

Shrimp paste alternatives

There are widely available vegan alternatives to shrimp paste that can be used to add umami flavor and/or texture to many dishes, such as miso paste, fermented bean paste, seaweed, vegan fish sauce, tamari, soy sauce, and shitake mushrooms (Dan & Jess, 2023). Recipes and tutorials for vegan versions of dishes that use shrimp paste can also be found on the internet.

Vegetarian and vegan shrimp paste are already commercially available in Southeast Asian countries. There are also recipes available to create homemade vegan shrimp pastes (Jeeca, 2021; Lainey, 2020).

| |||

| Figure 16. Vegan shrimp paste products from Australia (Red Lotus, n.d.), Vietnam (Prestashop, n.d.),Philippines (Plantlab, n.d.), Malaysia (Everleaf, n.d.) | |||

The small vegan shrimp paste industry faces two main challenges:

The first one is increasing market accessibility through lower selling prices. For example, in the Philippines, 1kg of fresh shrimp paste approximately costs Php 110 (~$2) while 225g of vegan shrimp paste costs around Php 275 (~$5). This makes the price per gram of the vegan shrimp paste approximately 10 times the price per gram of the animal product.

The second one is replicating the unique umami taste and texture of shrimp paste. Technological innovations are needed to both lower production costs and improve gastronomic properties.

Raising Consumer Awareness

Consumers can influence industry standards and government regulations. When consumers are well-informed about the conditions under which the Acetes shrimps are harvested and processed, they will be more likely to demand higher welfare standards and responsible sourcing. Awareness of the welfare issues and the food safety issues in commercial shrimp paste production may also make them more receptive to exploring shrimp paste alternatives.

Remaining research questions

The opportunities for intervention presented are informed by our knowledge of the shrimp paste industry, and interventions that have been explored for other wild-caught fishes. Further investigation and research on specific welfare problems in the industry are required to develop effective solutions.

Acetes shrimp sentience and welfare

What are the stress indicators and welfare conditions of Acetes shrimps during capture and processing?

When do the major mortality events occur in the fishery/production process?

Shrimp paste industry

What percentage of the wild-caught Acetes shrimps is consumed as a dried good and as processed shrimp paste? Is it possible that a significantly smaller portion of the catch is used to make shrimp paste?

What percentage of the industry is processed by big manufacturing facilities and small communities (sold in informal markets)? This could inform intervention approaches (i. e. corporate vs. community level).

Are there existing fishery regulations governing the fishing of Acetes shrimps in any of the Asian countries? Are these actively enforced?

Are health and safety standards set for commercial shrimp paste production, and are they actively enforced?

Fisher communities

How does intensive fishing affect the population dynamics of Acetes shrimps?

Could there be protected fishing zones enforced by the government?

How do cultural attitudes towards shrimp paste and Acetes shrimps affect the potential for welfare improvements?

What are the barriers for consumers to switch to vegan shrimp paste alternatives if they were cheaper?

What are the professions that fishers explore when Acetes shrimp are not abundant? Which alternative professions can the government or an NGO support to become sustainable?

References

Please find all the references here.

FWIW, shrimp paste alternatives seem morally ambiguous and have a significant risk of backfiring.

Shrimp paste alternatives would probably increase paste shrimp populations. If you think paste shrimp have overall bad lives naturally, then increasing their populations this way would be bad. If you’re highly uncertain about this, then the effects on their population would be highly morally ambiguous.

Shrimp paste alternatives could increase paste shrimp catch (if they’re overfished; see my recent post).

I don’t know how common this is or will be, but I’ve also seen a few articles about paste shrimp (mostly from India) being used as farmed animal feed, like fishmeal. Shrimp paste alternatives could divert paste shrimp catch towards feed and therefore support and increase aquaculture, including shrimp farming, where fishmeal typically makes up >10% of shrimp diets.[1] However, it could also make it harder for insects to compete as a fishmeal substitute, and so decrease insect farming.

Whether or not paste shrimp are fed to farmed shrimp, they could increase the supply and reduce the prices of fishmeal and fishmeal substitutes, and so reduce fishmeal prices for shrimp farms.

Thanks Michael! I was asking myself exactly these questions when reading the article.

Executive summary: The shrimp paste industry, which relies heavily on wild-caught Acetes shrimps, raises significant animal welfare concerns that warrant further research and potential interventions to reduce suffering.

Key points:

Acetes shrimps are likely the most utilized aquatic animal for food globally, with trillions harvested annually for shrimp paste production in Southeast Asia.

Shrimp paste production involves sun-drying, grinding, and fermenting the shrimp, and is deeply rooted in the region’s cultural heritage and cuisine.

Small coastal communities and larger manufacturing facilities are involved in the supply chain, both facing challenges related to fluctuating shrimp populations, food safety, and waste.

Acetes shrimps likely endure significant suffering during capture (injury, suffocation) and processing (osmotic shock, dehydration, stress) while still alive.

Potential interventions include developing gentler capture methods, implementing humane slaughter practices, and promoting vegan alternatives, but more research is needed on Acetes shrimp sentience and industry specifics.

Raising consumer awareness about welfare issues and responsible sourcing could help drive higher industry standards and regulations.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.