[Subtitle.] Sentience and moral priority-setting

This is a crosspost for The shrimp bet: When big numbers outsprint the evidence by Rob Velzeboer, which was originally published on 27 January 2026.

TLDR: Shrimp welfare looks like the ultimate “scale + tractability” slam-dunk: massive numbers, cheap fixes, grim-sounding deaths. But the flagship farmed species—the penaeid shrimp L. vannamei—is an evidential outlier: beyond basic nociception, the sentience case is close to empty, and the limited evidence we do have points the wrong way on key markers. In the report that kicked off this wave, it was included for administrative clarity, not because sentience looked likely. If you let precaution plus expected-value reasoning run on that evidential bar, you don’t stop at shrimp, but you get pulled into insects and the rest of modern life’s collateral killing. My view is that we shouldn’t let raw numbers and optimistic assumptions about sentience guide our moral priorities: most weight should go to high-confidence, severe, tractable suffering, and extremely low-confidence beings with high numbers should be treated as explicit research-and-standards bets, unless at least some higher-order evidence actually suggests pain.

“At least I’m not a shrimp.”

It’s a line I’d often repeat to myself back in 2016, when I started taking animal suffering seriously and realized how fortunate I was to live a human life.

Of course, to most people this thought sounds entirely absurd, especially those who don’t take animal sentience seriously. But I figured if you accept that animals, like ourselves, are sentient, that each has an individual life, and that we only get to live one life on this planet, then the odds that I’d be born human, rather than as a shrimp (or some other animal whose life plan is basically “get eaten”), were astronomically small.

By some crude moral arithmetic, I estimated that for every one human born on this planet, somewhere between 70-700 trillion shrimp-like creatures were born, living short lives and meeting what I assumed were horrible deaths, likely being acidified inside a predator’s stomach.

I didn’t know whether this was fully accurate, but the possibility felt overwhelming. By sheer statistical luck, we won the jackpot of human existence, and did so in an era of unprecedented peace, medicine, knowledge, and wealth.

This shrimp sentience thought experiment is no longer just hypothetical. Whether shrimp can feel pain—and if so, how much—has become a central and increasingly serious debate within suffering-focused practical ethics, particularly among effective altruists (EAs), and has gained mainstream coverage in newspapers such as The Guardian[1] and Vox[2].

The 2021 report that set off EAs’ focus on this issue—Review of the Evidence of Sentience in Cephalopod Molluscs and Decapod Crustaceans[3]—was led by Jonathan Birch, who acted as the supervisor of my Master’s dissertation on how cognitive sophistication affects moral status. So as a former animal sentience student who is focused on reducing suffering, I felt compelled to dig into the evidence to see if my beliefs about moral priorities needed updating.

PART 1: SHRIMP

Why focus on shrimp

My default view has been that those who are serious about reducing suffering should focus on the plight of chickens. Not just because their living conditions are clearly bad[4][5], but precisely because they are so numerous[6], particularly when compared to cows[7], and the number we kill looks to keep growing rapidly for at least the next few decades[8][9]. I thus share most of the underlying beliefs of those who promote focus on shrimp welfare: the scale, tractability, and neglectedness of pain matter.

Shrimp are the perfect case to match this logic: their scale is enormous (farmed shrimp amount to close to half a trillion a year[10]—about five to six times as many as chickens, and more than 1,500 times as many as cows), their death seems painful (they tend to be killed in ice slurries, freezing to death[11]), improvements are highly tractable (simply using electric stunners rather than ice baths makes their death instant rather than potentially painful and drawn out), and, until recently, no one was doing anything about it.

The cost to improve things? About $1 per 1,000-1,500 shrimp that are switched from slowly freezing to being instantly electrically stunned to death[12]. May sound macabre, but if the logic holds, it’s hard to argue you can get a better welfare bang for your buck. [Slowly asphyxiating is more accurate than slowly freezing according to Aaron Boddy, Shrimp Welfare Project’s (SWP’s) chief strategy officer. 1 k to 1.5 k shrimps helped per $ assumes the electrical stunning is adopted 1 year earlier. I guess the acceleration is more like 7.5 years, which implies 10.5 k shrimps helped per $ (= 7.5*1.4*10^3) for SWP’s estimate of 1.4 k shrimps helped per year per $.]

Despite their sheer number, I’ve historically placed less moral priority on aquatic animals like shrimp. Part of this is undoubtedly terrestrial bias, but much of it is evidential.

For wild-caught aquatic animals—the majority of seafood by biomass up until 2024[13]—I’ve never been too convinced that human capture is that morally distinctive from the violent deaths these animals would otherwise face in nature. Among farmed ones, the welfare picture is also far less clear than it is for terrestrial livestock[14]: we lack strong evidence that their lives are dominated by the kinds of chronic growth disorders, infections, and injuries that seem to make the lives of animals like chickens a net negative[15][16].

Most importantly, we simply weren’t sure whether many aquatic animals feel pain at all[14]. While the evidence for pain in fish has grown increasingly persuasive[3], shrimp in particular remained a genuine question mark.

Enter Birch’s work. In his 2024 book The Edge of Sentience[17], he offers a framework for decision-making under uncertainty about a being’s sentience. He argues that when there is credible evidence placing one near the “edge of sentience,” the asymmetry of moral risk favors precaution: the harm of mistakenly denying sentience to a sentient being is typically much greater than the harm of mistakenly extending protections to a non-sentient one.

His sentience framework reviews evidence for sentience across eight criteria:

1. Presence of nociceptors

2. Integrative brain regions

3. Connections between nociceptors and integrative brain regions

4. Responses affected by local anesthetics or analgesics

5. Motivational trade-offs

6. Flexible self-protective behavior

7. Associative learning that goes beyond habituation or sensitization

8. Behavior indicating valuation of analgesia

As more of these criteria are met, Birch argues, it becomes increasingly implausible that no phenomenological, subjectively felt experience is present. At some point, it is more reasonable to assume that the animal feels something, however minimal, than that it performs complex behavior in a complete experiential vacuum[17].

His decapod review, which recommends “that all cephalopod molluscs and decapod crustaceans be regarded as sentient animals for the purposes of UK animal welfare law,”[3] (p.8) has been highly influential. It helped inform the UK government’s decision to include crustaceans within animal welfare law[18][19]—effectively banning practices such as boiling lobsters alive—and now serves as the central evidence cited by shrimp welfare advocates.

The evidence for shrimp pain

What should stand out right away in the decapod review is that the evidence varies dramatically across taxa. Among the six decapod taxa reviewed, true and anomuran crabs have been relatively well-studied, astacid lobsters, spiny lobsters, and caridean shrimp less so, and the shrimp species most commonly consumed by humans—Litopenaeus vannamei[20][21]; part of the penaeid shrimp family and the focus of shrimp welfare projects—sits at the bottom of this evidence spectrum.

L. vannamei scores low confidence on all but two of the eight criteria, the exceptions being (1) presence of nociceptors and (4) responses affected by local anesthetics or analgesics. Importantly, “low confidence” for a criterion here often means we don’t know, rather than negative findings: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and L. vannamei remains understudied on most of the criteria[3] (p.6).

The most direct behavioral finding supporting pain experience in L. vannamei is that during the common industry procedure of eyestalk ablation—the cutting of one or both eyestalks to accelerate maturation[22][23]—they exhibit reactions such as erratic swimming and tail flicking, which is reduced by the topical application of the anesthetic lidocaine[24].

This suggests the reaction may involve nociceptive pathways that can be dampened pharmacologically, which is consistent with possible pain experience. But rather than specific relief of pain or an aversive state, it could also simply reflect generalized motor suppression or reduced responsiveness.

Beyond this, the picture for L. vannamei is muddy. One study on a caridean shrimp species—not peneaid, like L. vannamei—called Palaemon elegans, found that exposure of one antenna to low-pH acetic acid or high-pH sodium hydroxide elicited location-specific grooming and rubbing behavior—indicative of pain or irritation—which was attenuated by the local anesthetic benzocaine[25].

However, a later study, using three decapods—including the penaeid shrimp Litopenaeus setiferus, a close relative of L. vannamei—found no such directed grooming or rubbing, even when stronger pH stimuli were used[26].

Given the lack of solid direct evidence, the case for pain in L. vannamei is thus often an argument by association: better-studied decapods such as crabs and lobsters show evidence of pain-like behavior, so it’s argued that L. vannamei likely has similar capacities[27].

As noted, the decapod report concludes with the recommendation to include all decapods, including L. vannamei, in animal welfare law. But Birch is candid about what this policy recommendation actually rests on.

In the conclusion, he writes:

“We have noted that there is very little evidence of sentience at present in penaeid [including L. vannamei] shrimps. However, if caridean shrimps were included, but penaeid [L. vannamei] shrimps excluded, the potential for confusion [emphasis added] would be high. Therefore, on balance, we reject the suggestion that protection should only be extended to specific infraorders of decapod.”[3] (p.81)

L. vannamei gets included not because the evidence converges on “sentience looks likely,” but because excluding them while including other shrimps would make the law confusing in practice. So even within Birch’s broadly precautionary posture, L. vannamei are an awkward outlier, included for administrative clarity rather than scientific confidence.

Three years after the decapod report, he sharpens and explains this choice in his book[17], noting that a neuroanatomical survey found that decapods generally have “hemiellipsoid bodies”[28]—integrative regions linked to learning and memory—but that in L. vannamei specifically, these regions appear miniaturized and weakly differentiated[17] (p.256).

Birch emphasizes why this matters: nervous tissue is metabolically expensive to run, so dramatic reduction is often what we expect to see when a system is no longer functionally significant. On this basis, he reports low confidence that L. vannamei has functional integrative brain regions—not that such regions are entirely absent, but that the evidence does not support treating them as doing substantial integrative work. Without integration, it becomes harder to confidently argue an animal is feeling pain, rather than merely reacting through nociceptors.

He then draws a sharper taxonomic line: Pleocyemata—walking decapods and caridean shrimps—do count as sentience candidates (the evidence is substantial enough to warrant some precaution), while Dendrobranchiata, which include penaeid shrimps such as L. vannamei, do not[17] (p.258-262). In other words, across the six decapods he reviews, L. vannamei is the only one he does not class as a sentience candidate.

And that matters, because the move made by some shrimp advocates is extrapolation: if crabs and lobsters show pain-like responses, it is argued shrimp probably do too. For example, one commonly cited welfare-range model explicitly approximates shrimp’s probability of sentience as equivalent to the prior distribution used for crabs[29]. But critics point out that, given the structural differences between decapod lineages, this kind of taxonomic borrowing across suborders is shaky[30].

None of this is a full denial of sentience in L. vannamei, and Birch entertains the possibility that some lineages could evolve integrative capacities and later lose them. But the practical conclusion he draws is that L. vannamei is precisely a case where the integrative-architecture story looks too insecure and the evidential base too thin to treat sentience as likely, even within a precautionary framework[17] (p.257-258).

Because of the lack of research on L. vannamei and potentially large welfare stakes, Birch places them into the “investigative priority” category, together with beings such as worms and insect larvae[17] (p.276-281).

Skepticism

The overall L. vannamei evidence picture, in terms of where (very few) studies actually exist, thus looks roughly like this: there is high confidence that they (1) possess nociceptors and medium confidence that (4) their responses can be modulated by local anesthetics or analgesics[3][24]. There is low confidence that they (2) have functional integrative brain regions[3][28][31] or (6) that they show self-protective behavior in response to noxious stimulation[3][26].

There appear to be no studies bearing on (3) connections between nociceptors and integrative brain regions, (5) motivational trade-offs, (7) associative learning, or (8) behavior suggesting valuation of analgesia. And while that absence is not decisive, it matters that—to my knowledge—there are no animals for which these higher-order criteria are supported in the absence of at least some confidence in (2).

Even allowing for selection effects, nociceptors alone are doing virtually all the work here, which is essentially a baseline feature across the animal kingdom. And if we can’t safely generalize from related taxa, the sentience case for L. vannamei becomes extremely thin.

A plausible reason we commonly see framing along the lines of “we just haven’t studied shrimp enough yet, but it’s reasonable to assume they likely feel pain based on other decapods” is Birch et al.’s confidence scoring itself. In their system, low confidence can reflect two very different situations: either that a criterion has not been investigated in the relevant species, or that it has been investigated and the results have been weak or negative.

As a result, it is easy to read the gap between shrimp and better-studied decapods as only a research gap. And to a large extent, that’s true. But the limited evidence that is available is unsupportive on two crucial pain-relevant markers. This ambiguity in what “low confidence” denotes—an issue brought up by critics of Birch’s original approach[30], which he appears to have addressed in later reports[32]—could therefore blur the distinction between “we don’t know yet” and “the evidence so far leans against”.

Another place where some caution about confidence is warranted is the welfare impact of ice slurry, the slaughter method often contrasted with electrical stunning.

Electrical stunning is rightly treated as one of the most humane commercially available options because it is designed to render animals rapidly insensible[33]. However, Birch, while recommending it as best current practice based on the available evidence (and indeed ahead of ice slurry), is explicit that we still don’t know what the neural activity induced by electrical stunning feels like from the animal’s point of view, or whether the resulting unresponsive state is truly unconsciousness rather than some form of continuing experience[3] (p.71-72).

At the same time, we also don’t fully know whether chilling (from ice slurry) is actually painful in shrimp[3] (p.73)[34], and its effects are at least not uniform across species. One review notes that lobsters and crabs retained sensory-central nervous system responses in very cold conditions—suggesting chilling may not reliably anesthetize them—but for L. vannamei it describes a rapid collapse in activity when transferred to ice, interpreted by the authors as consistent with anesthesia[33]. This is a liberal interpretation, however, since reduced activity alone cannot establish insensibility.

None of this shows that ice slurry is humane or painless, and electrical stunning does have the strongest welfare-based rationale. But it does make confident “ice = obvious agony” or “electrical stunning = painless” harder to state as if it’s fact. The Shrimp Welfare Project is trying to get more peer-reviewed scientific data on this issue[11], which is a good thing.

This is also not at all to say that the science on L. vannamei is anywhere near settled, or that more evidence on their potential sentience isn’t needed. But I do think taking the case seriously based on current evidence opens an—almost literally—enormous can of worms.

PART 2: PRIORITIZATION

The implications of this view

Indeed, if one does consider the case for L. vannamei as being enough to warrant precaution and acting on it, then Birch’s own consistency arguments make it hard to deny comparable consideration to at least ants, fruit flies, and mosquitoes.

In fact, when these same sentience criteria are applied to insects, as Birch and colleagues have done in another report, flies and mosquitoes score high to very high confidence evidence for six out of eight criteria, and ants do so for four out of eight, compared to only one criterion for L. vannamei[32]. Importantly, this includes a functional central complex that L. vannamei appears to lack. Birch indeed proposes that, unlike L. vannamei, all adult insects are sentience candidates[17] (p.272).

We currently farm and kill about one trillion insects, and this is expected to increase to about ten trillion by 2030[35] (though estimates vary). Slaughter methods include boiling, freezing, freeze-drying, blast drying, spraying with hot water, mechanical crushing, and shredding[17] (p.294), most if not all of which may be extremely painful.

By precautionary expected value reasoning, insects appear to make a stronger case than shrimp: they show more markers of sentience, are much larger in (projected) scale, and killed in equally (if not more) seemingly painful ways. Tractability might be one point where shrimp is stronger, though active work on insect welfare practices[36], instantaneous killing[36][37] and humane insecticides[38] could well exceed it there too.

Birch’s framework is designed for ethical decision-making under uncertainty, where the evidence is incomplete, and the potential downside of getting it wrong could be massive. The difficulty is that, once you combine this precautionary posture with EA-style expected value reasoning, the moral priorities landscape easily gets hijacked by these low-probability, ultra-high-scale cases.

Insects are stitched into the basic metabolism of life: conservative estimates place annual insect deaths in agriculture at hundreds of trillions; others, once you include pesticides, habitat destruction, and crop harvesting, estimate around 3.5 quadrillion[17][38]. That’s about half a million insects per human per year.

A tiny credence multiplied by an astronomical number of individuals multiplied by even very modest negative experience thus threatens to dominate moral attention. If one considers shrimp welfare as the “precautionary frontier,” by this logic, insects aren’t at the frontier, but already over the line. On this view, the main ethical crisis built into modern life is the quadrillions of insects we kill just to move around, wash, and eat food—under our shoes, beneath our tires, in our sinks, and across our food crops.

And there the epistemic problem becomes practical: when you cut back on meat, you can tell a legible story—avoid something like ~10 chicken meals and, roughly, one chicken doesn’t have to be raised and killed—but with insects you can’t even define, let alone verify, the “insects not killed” counterfactual, so the moral arithmetic starts to outrun anything a human can responsibly act on. Just one fruit salad might rack up more deaths than your conscience can even render.

We can accept this “moral explosion” if we think it is simply the logical consequence of an otherwise coherent worldview—one that gestures toward something Benatarian: a view on which the cleanest way to reduce suffering appears to be to reduce sentient life itself[39]. That’s not to say it’s definitively wrong; perhaps the world really is largely made up of enormous invertebrate suffering.

Alternatively, we can try to add principled constraints that prevent low-confidence, ultra-high-n cases from hijacking the moral landscape.

Birch manages some of the high-n runaway logic through proportionality (distinguishing unavoidable collateral harms from avoidable, high-risk practices; e.g., accidentally stepping on an ant vs. killing ants for food without effective stunning)[17] (p.154-170); democratic deliberation (using informed citizen processes to settle what trade-offs are proportionate)[17] (p.138-153); and making distinctions between sentience candidates and investigation priorities (the former getting precaution, the latter urgently needing more research)[17] (p.123-127), which are sensible brakes for governance as they prevent policy whiplash.

However, besides it seeming unlikely people will ever care about mosquito welfare—even after fifty years of modern animal advocacy[40] there is little evidence of a shift away from industrially farmed animal products at the population level, with chicken slaughter per person roughly quadrupling during this period[6][7]—these constraints don’t solve the cause-prioritization problem, because they don’t tell you how to compare 10 billion high-confidence extreme sufferers against 10 trillion low-confidence ones.

And even granting the usual EA filters—tractability, neglectedness, feasibility, and evidential robustness—the scale gradient from shrimp to insects (via agriculture-related deaths) is so steep that these filters don’t, by themselves, explain why the precautionary logic should settle on shrimp. All else equal, once you shift to a target that is thousands of times larger, an intervention could be far less effective [in terms of robustly increasing welfare in expectation] and still compete on expected impact.

Pain severity

I think it helps here to consider a set of observations that Birch collects that, whatever they ultimately imply about sentience, sit awkwardly with our usual inferences about suffering.

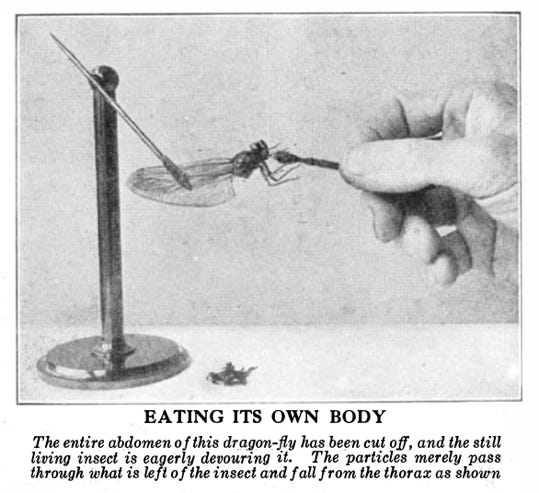

He notes that insects “will continue normal feeding and mating behaviours despite catastrophic injury”[17] (p.264), with examples including “a dragonfly eating its own detached abdomen” and “a sleeping moth that is not woken by being pinned to a tree”[17][41] (p.264).

Though based on observation rather than experimentation—so not proper evidence in the clinical sense—Eisemann et al. describe their insect pain behavior observations in unusually vivid terms:

“… our experience has been that insects will continue with normal activities even after severe injury or removal of body parts. An insect walking with a crushed tarsus, for example, will continue applying to the substrate with undiminished force. Among our other observations are those on a locust which continued to feed whilst itself being eaten by a mantis; aphids continuing to feed whilst being eaten by coccinellids; a tsetse fly which flew in to feed although half-dissected; caterpillars which continue to feed whilst tachinid larvae bore into them; many insects which go about their normal life whilst being eaten by large internal parasitoids; and male mantids which continue to mate as they are being eaten by their partners.”[42]

Even if insects have aversive experience, this injury-tolerance profile suggests that severe injury does not reliably manifest as the kind of global motivational suppression we normally associate with intense, disabling suffering in other animals.

That does not settle the sentience question. The profile could reflect brief or highly local negative states, limited integration, context-dependent suppression of protective behavior, or simply that our behavioral heuristics do not transport across taxa. It should be noted here too that there is some evidence of wound-tending in cockroaches and moth larvae[32], as well as evidence of motivational trade-offs in fruit flies[43] and bees[32][44].

[I recommend reading Meghan Barrett’s and Bob Fischer’s thoughts on whether insects often behave normally after severe injuries. “evidence for this claim is entirely anecdotal, and not based on a quantitative, methodologically rigorous survey of insects’ responses to different injuries. Quantitative analysis might indicate that many of these behaviors are actually unusual”.]

Still, taken as a whole, the pattern is at least compatible with the notion that a tiny, low-neuron nervous system may be sentient in a thin sense while having sharply limited capacity for integrated, persistent, life-dominating negative states. Of course, this remains a substantive assumption, and one that we may never get definitive answers to. (And no, neuron counts aren’t good moral status proxies; yes, they can plausibly constrain pain capacity.)

Indeed, the current insect and general sentience literature is much better at answering “can they avoid or respond to noxious stimuli?” than “can they enter sustained, life-dominating distress?” Sentience markers often function as threshold tests but are poorly calibrated to severity. And the feasibility of “properly” studying pain severity in a clinical way (beyond observation) by intentionally inducing prolonged distress states seems ethically fraught and experimentally intractable.

The issue with severity is that it’s a felt state that we don’t get access to in other species. Even in humans, severity is not read directly off behavior or physiology; it’s inferred from a bundle of self-report, choice, and bodily signals. In nonhumans we can’t prove severity, but we can find some markers. When an adverse state produces persistent, system-wide motivational collapse (reduced feeding, exploration, sociality, mating), scales with objective harm (lesion burden, disease severity), and reverses under interventions that reduce harm, that is at least consistent with a life-interfering negative condition, not just local avoidance.

Conversely, when catastrophic injury leaves behavior broadly intact (feeding and mating continue with little suppression), that pushes the plausible interpretation toward highly local, easily overridden aversion, extreme compartmentalization, or no aversive experience at all. None of this delivers certainty, but it does bear on whether the system plausibly supports severe pain. We cannot establish that insect negative experience is “thin,” but it is a tenable interpretation.

On a severity weighting view, moral priority-setting turns on what kinds of negative states a system can support. It can be encoded as a strict override (the controversial lexical priority view that even a moment of excruciating pain defeats any amount of moderate discomfort, which has serious issues[45]), or more modestly as extreme weights that make “disabling” or “excruciating” pain dominate “annoying” or “hurtful” pain by large orders of magnitude.

There is some empirical support for the general shape of this idea: in evaluations of aversive episodes people tend to overweight peak intensity and show surprising insensitivity to duration[46][47][48][49][50][51][52], and pain unpleasantness appears to increase extremely nonlinearly with intensity[53][54][55]. The Welfare Footprint Institute’s categories make this discontinuity in pain explicit: “annoying” and “hurtful” still leave room for positive welfare, whereas “disabling” and “excruciating” are, by definition, inconsistent with it[53].

Put succinctly, there is a (perhaps qualitative) difference between local aversions that leave a life largely intact and states that can crowd out positive experience and become life-dominating. A simple way to see the distinction is to consider mild human discomforts: a low-grade dehydration headache, a brief chill, a tired jaw from chewing too hard. Multiply those annoyances across billions of people and you can generate an enormous aggregate “amount” of unpleasantness, yet it seems hard to argue this is the kind of suffering that should dominate moral attention. What plausibly deserves priority are states that are severe and disabling—agonizing terminal illness, never-ending cluster headaches, debilitating depression, or sustained disabling states like severe lameness under rapid growth, suffocation from ascites, or stunning failures that leave one conscious through intense fear and pain at slaughter.

You don’t need a precise exchange rate to see the shape of the moral landscape on this view: it allows large numbers to matter in some way, while giving special weight to evidence-backed, severe, life-disrupting suffering. The critical question is whether shrimp or insects can support the kinds of negative states that make suffering severe, rather than merely possible.

Prioritization

On the pro side, shrimp welfare has a rare combination of features that make an intervention attractive: large numbers, a concrete and legible intervention, and a plausible story of large gains at very low cost. On the view that we shouldn’t wait for proof when the downside risk could be large, shrimp appear like a reasonable place to act, especially insofar as the interventions are relatively low-regret and may generate spillovers like improved industry norms for other aquatic invertebrates—simply stunning before killing is a pretty low bar.

But the case is weaker than it often sounds, because the flagship species, L. vannamei, is supported by almost the thinnest evidential profile you can possibly have while still talking about pain at all. Beyond nociceptors, there is no good evidence for sentience, and some evidence that is unsupportive. Among the six decapods he has reviewed, it is telling that Birch only excludes L. vannamei from sentience candidacy. If you respond to that level of uncertainty with precaution plus expected-value arithmetic, the logic expands to insects more strongly, given their stronger sentience markers and their vastly larger numbers (and they are, indeed, considered “sentience candidates”).

The severity-weighted approach seems attractive in cases like this: it does not deny that thin, uncertain harms can matter, but it says we should be cautious about letting astronomical low-certainty beings dominate the moral landscape when we remain unsure about both sentience and the capacity for severe, integrated distress. The empirical problem is that welfare science is much better at detecting negative states of some kind than at measuring how intense those states are, and it is far better developed for vertebrates than for invertebrates. Much of what passes for “severity” inference leans on vertebrate-centric proxies and human analogies, and the injury-tolerance cases in insects suggest those analogies may not transfer. However, if even spectacular tolerance to ripped off limbs can’t count as any evidence against life-dominating distress, then it’s unclear what observable pattern could ever count against it—and “severity” risks becoming insulated from evidence.

A final friction is practical: shrimp welfare is, unavoidably, a bet. If penaeid shrimp turn out not to be sentient, which I think is a plausible read given current evidence, the direct welfare impact collapses to near zero (leaving only indirect spillovers like better standards). That’s a different kind of intervention from high-certainty cases, where the same dollars almost certainly reduce felt suffering, and such funding is desperately needed. That trade-off matters.

In practice, this pushes me toward a portfolio view with heavy emphasis on proven, serious suffering. I’d put the bulk of effort into high-confidence, disabling to severe suffering, ideally with proven interventions, and reserve a small share for high-n uncertain cases—treated more like research, standards-setting, and low-regret improvements than like a primary welfare bet. The precise percentages aren’t the point; where the chance of near-zero direct impact is substantial, it’s rational to limit how much you stake on it, and treat the work as a smaller, exploratory allocation.

On that view, shrimp welfare can be a component, particularly as a research and standards target, but not the default priority implied by simple “scale + tractability” arithmetic. I’d find shrimp welfare a bit more compelling if confidence accumulates that they can at least meet one basic sentience criterion outside of nociception—especially a higher-order one (5-8). Until then, I think it’s reasonable to act with modesty: to treat it as worth some attention, but to resist the feeling that the numbers should settle what we ought to do, and to keep our focus on reducing large-scale severe suffering in proven cases.

Disclosure: I’m not neutral. I’ve focused on chicken welfare since at least 2017. I should also note that in my 2020 LSE thesis I defended a fairly binary view of pain—either a being can suffer in a robust way, or it can’t suffer at all—I’m less confident in that picture now. Some of that is genuine updating, but some of it might be motivated reasoning too.

- ^

Stock P. Do prawns feel pain? Why scientists are urging a rethink of Australia’s favoured festive food. The Guardian [Internet]. 2025 Dec 21 [cited 2026 Jan 8]; Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/dec/22/crustaceans-feelings-sentient-christmas-new-year-prawns-australia

- ^

Matthews D. The case for caring about shrimp. Vox [Internet]. 2025 Sep 11 [cited 2026 Jan 8]; Available from: https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/461008/shrimp-welfare-project-controversy

- ^

Birch J, Burn C, Schnell A, Browning H, Crump A. Review of the Evidence of Sentience in Cephalopod Molluscs and Decapod Crustaceans [Internet]. London School of Economics and Political Science; 2021 Jan. Available from: https://www.lse.ac.uk/News/News-Assets/PDFs/2021/Sentience-in-Cephalopod-Molluscs-and-Decapod-Crustaceans-Final-Report-November-2021.pdf.

- ^

Schuck-Paim C, Alonso WJ. Quantifying Pain in Broiler Chickens: Impact of the Better Chicken Commitment and Adoption of Slower-Growing Breeds on Broiler Welfare. 2022. 458 p.

- ^

Schuck-Paim C, Alonso WJ. Quantifying Pain in Laying Hens: A blueprint for the comparative analysis of welfare in animals. 2021. 338 p.

- ^

Surveys—Poultry Slaughter [Internet]. United States Department of Agriculture—National Agricultural Statistics Service; 2024. Available from: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Surveys/Guide_to_NASS_Surveys/Poultry_Slaughter/index.php

- ^

Surveys—Livestock Slaughter [Internet]. United States Department of Agriculture—National Agricultural Statistics Service; 2024. Available from: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Surveys/Guide_to_NASS_Surveys/Livestock_Slaughter/index.php

- ^

Global meat consumption [Internet]. Our World in Data. [cited 2026 Jan 20]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-meat-projections-to-2050

- ^

Jia J, Dawson TP, Wu F, Han Q, Cui X. Global meat demand projection: Quo Vadimus? Journal of Cleaner Production. 2023 Dec 1;429:139460.

- ^

McKay H. Three Numbers That Make The Case For Shrimp Welfare [Internet]. Faunalytics. 2024 [cited 2026 Jan 20]. Available from: https://faunalytics.org/three-numbers-that-make-the-case-for-shrimp-welfare/

- ^

Humane Slaughter for Shrimp: Q&A with Shrimp Welfare Project [Internet]. Shrimp Insights. 2026 [cited 2026 Jan 20]. Available from: https://www.shrimpinsights.com/advertorial/humane-slaughter-shrimp-qa-shrimp-welfare-project

- ^

(Shr)Impact [Internet]. Shrimp Welfare Project. [cited 2026 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.shrimpwelfareproject.org/shrimpact

- ^

The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture [Internet]. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2024 [cited 2026 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/publications/fao-flagship-publications/the-state-of-world-fisheries-and-aquaculture/en

- ^

Browman HI, Cooke SJ, Cowx IG, Derbyshire SWG, Kasumyan A, Key B, et al. Welfare of aquatic animals: where things are, where they are going, and what it means for research, aquaculture, recreational angling, and commercial fishing. ICES J Mar Sci. 2019 Jan 1;76(1):82–92.

- ^

Bessei W. Welfare of broilers: a review. World’s Poultry Science Journal. 2006 Sep;62(3):455–66.

- ^

Broilers | Pain Track [Internet]. Welfare Footprint Institute. [cited 2026 Jan 11]. Available from: https://cp.pain-track.org/broilers

- ^

Birch J. The Edge of Sentience: Risk and Precaution in Humans, Other Animals, and AI [Internet]. Oxford University Press; 2024 [cited 2026 Jan 11]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/9780191966729.001.0001

- ^

Lobsters, octopus and crabs recognised as sentient beings [Internet]. GOV.UK. [cited 2026 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/lobsters-octopus-and-crabs-recognised-as-sentient-beings

- ^

Courea E. Boiling lobsters alive to be banned in England amid animal cruelty crackdown. The Guardian [Internet]. 2025 Dec 22 [cited 2026 Jan 11]; Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/dec/22/boiling-lobsters-alive-banned-animal-cruelty-crackdown

- ^

Liao IC, Chien YH. The Pacific White Shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, in Asia: The World’s Most Widely Cultured Alien Crustacean. In: Galil BS, Clark PF, Carlton JT, editors. In the Wrong Place—Alien Marine Crustaceans: Distribution, Biology and Impacts [Internet]. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2011 [cited 2026 Jan 11]. p. 489–519. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0591-3_17

- ^

Cheney J. An Overview of Shrimp and its Sustainability in 2024 [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2026 Jan 11]. Available from: https://sustainablefisheries-uw.org/shrimp-sustainability-2024/

- ^

Lumare F. Reproduction of Penaeus kerathurus using eyestalk ablation. Aquaculture. 1979 Nov 1;18(3):203–14.

- ^

Sainz-Hernández JC, Racotta IS, Dumas S, Hernández-López J. Effect of unilateral and bilateral eyestalk ablation in Litopenaeus vannamei male and female on several metabolic and immunologic variables. Aquaculture. 2008 Oct 1;283(1):188–93.

- ^

Taylor J, Vinatea L, Ozorio R, Schuweitzer R, Andreatta ER. Minimizing the effects of stress during eyestalk ablation of Litopenaeus vannamei females with topical anesthetic and a coagulating agent. Aquaculture. 2004 Apr 26;233(1):173–9.

- ^

Barr S, Laming PR, Dick JTA, Elwood RW. Nociception or pain in a decapod crustacean? Animal Behaviour. 2008 Mar 1;75(3):745–51.

- ^

Puri S, Faulkes Z. Do Decapod Crustaceans Have Nociceptors for Extreme pH? PLOS ONE. 2010 Apr 20;5(4):e10244.

- ^

Are Shrimps Sentient? [Internet]. Shrimp Welfare Project. [cited 2026 Jan 12]. Available from: https://www.shrimpwelfareproject.org/are-shrimps-sentient

- ^

Strausfeld NJ, Wolff GH, Sayre ME. Mushroom body evolution demonstrates homology and divergence across Pancrustacea. Behrens TE, Carr CE, Carr CE, Osorio D, Katz P, editors. eLife. 2020 Mar 3;9:e52411.

- ^

Fischer. Rethink Priorities’ Welfare Range Estimates [Internet]. Rethink Priorities. 2023 [cited 2026 Jan 26]. Available from: https://rethinkpriorities.org/research-area/welfare-range-estimates/

- ^

Mallatt J, Feinberg TE. Decapod sentience: Promising framework and evidence. Animal Sentience. 2022 Jan 1;7:1.

- ^

Meth R, Wittfoth C, Harzsch S. Brain architecture of the Pacific White Shrimp Penaeus vannamei Boone, 1931 (Malacostraca, Dendrobranchiata): correspondence of brain structure and sensory input? Cell Tissue Res. 2017 Aug;369(2):255–71.

- ^

Gibbons M, Crump A, Barrett M, Sarlak S, Birch J, Chittka L. Can insects feel pain? A review of the neural and behavioural evidence. In: Advances in Insect Physiology [Internet]. Academic Press; 2022 [cited 2026 Jan 12]. p. 155–229. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/chapter/bookseries/pii/S0065280622000170

- ^

Rotllant G, Llonch P, García del Arco JA, Chic Ò, Flecknell P, Sneddon LU. Methods to Induce Analgesia and Anesthesia in Crustaceans: A Supportive Decision Tool. Biology. 2023 Mar;12(3):387.

- ^

McKay H, McAuliffe W, Romero Waldhorn D. Welfare considerations for farmed shrimp. 2023 Dec 7 [cited 2026 Jan 22]; Available from: https://osf.io/yafqv

- ^

Barrett M, Fischer B. Challenges in farmed insect welfare: Beyond the question of sentience. Anim Welf. 2023 Jan 26;32:e4.

- ^

Insects raised for food and feed — global scale, practices, and policy [Internet]. Rethink Priorities. 2020 [cited 2026 Jan 23]. Available from: https://rethinkpriorities.org/research-area/insects-raised-for-food-and-feed/

- ^

Barrett M, Miranda C, Veloso IT, Flint C, Perl CD, Martinez A, et al. Grinding as a slaughter method for farmed black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae: Empirical recommendations to achieve instantaneous killing. Anim Welf. 2024 Mar 12;33:e16.

- ^

Howe H. Improving pest management for wild insect welfare [Internet]. Wild Animal Initiative. 2021 [cited 2026 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.wildanimalinitiative.org/library/humane-insecticides

- ^

Benatar D. The Human Predicament: A Candid Guide to Life’s Biggest Questions. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017. 288 p.

- ^

Singer P, Harari YN. Animal Liberation Now: The Definitive Classic Renewed. New York: Harper Perennial; 2023. 368 p.

- ^

Bastin H. Do Insects Feel Pain? Scientific American. 1927;137(6):531–531.

- ^

Eisemann C, Jorgensen W, Rice M, Cribb B, Webb P, Zalucki M. Do insects feel pain? — A biological view. Experientia. 1984 Feb 1;40:164–7.

- ^

Kaun KR, Azanchi R, Maung Z, Hirsh J, Heberlein U. A Drosophila model for alcohol reward. Nat Neurosci. 2011 May;14(5):612–9.

- ^

Gibbons M, Versace E, Crump A, Baran B, Chittka L. Motivational trade-offs and modulation of nociception in bumblebees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2022 Aug 2;119(31):e2205821119.

- ^

Huemer M. Lexical Priority and the Problem of Risk. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly. 2010;91(3):332–51.

- ^

Fredrickson BL, Kahneman D. Duration neglect in retrospective evaluations of affective episodes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65(1):45–55.

- ^

Redelmeier DA, Kahneman D. Patients’ memories of painful medical treatments: real-time and retrospective evaluations of two minimally invasive procedures. Pain. 1996 Jul 1;66(1):3–8.

- ^

Kahneman D, Fredrickson BL, Schreiber CA, Redelmeier DA. When More Pain Is Preferred to Less: Adding a Better End. Psychol Sci. 1993 Nov 1;4(6):401–5.

- ^

Redelmeier DA, Katz J, Kahneman D. Memories of colonoscopy: a randomized trial. Pain. 2003 Jul 1;104(1):187–94.

- ^

Auriemma CL, O’Donnell H, Jones J, Barbati Z, Akpek E, Klaiman T, et al. Patient perspectives on states worse than death: A qualitative study with implications for patient-centered outcomes and values elicitation. Palliat Med. 2022 Feb 1;36(2):348–57.

- ^

Patrick DL, Starks HE, Cain KC, Uhlmann RF, Pearlman RA. Measuring preferences for health states worse than death. Med Decis Making. 1994;14(1):9–18.

- ^

Wade JB, Hart RP. Attention and the stages of pain processing. Pain Med. 2002 Mar;3(1):30–8.

- ^

Alonso WJ, Schuck-Paim C. Pain-Track: a time-series approach for the description and analysis of the burden of pain. BMC Res Notes. 2021 Jun 5;14(1):229.

- ^

Schuck-Paim C, Alonso WJ, Hamilton C. Short agony or long ache: comparing sources of suffering that differ in duration and intensity [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2026 Jan 20]. Available from: https://welfarefootprint.org/2024/02/20/shortagony-or-longache/

- ^

Gómez-Emilsson A, Percy C. The Heavy-Tailed Valence Hypothesis: The human capacity for vast variation in pleasure/pain and how to test it [Internet]. PsyArXiv; 2022 [cited 2026 Jan 20]. Available from: https://osf.io/krysx_v1

I know the OP may not read this comment. I made it on his Substack post and I’m sharing it here in case it’s of interest to others on the Forum.

Thanks for your post, Rob. Meghan Barrett and I have a detailed reply to Eisemann et al. 1984 in the Quarterly Review of Biology. You can see it here:

journals.uchicago.edu/d…

Short version, very little in that paper has stood the test of time and the particular passage you quote has many problems. I’d encourage you to reconsider including it!

Hi Rob. A few more thoughts. I grant you that the evidence for sentience in PWS is thin and I certainly don’t want to suggest otherwise. Still, I’m not sold on some of the bases for skepticism that you’ve flagged.

First, you suggest that the miniaturized hemiellipsoid bodies in PWS provide evidence against integrative processing of the sort relevant to pain. That inference is plausible in some contexts, but not all. Small structures can be highly functional, and in small animals “miniaturization” is often just what efficiency looks like rather than what loss looks like. After all, selective pressures have done that in many other species and current breeding practices are, effectively, intense selective pressures: they might push toward compact integrative circuitry rather than cause the loss of integration. In addition, morphology is a weak proxy for function. For instance, people used to think that the mushroom bodies in insects were solely for processing olfactory information, largely because the olfactory afferents were obvious and the visual inputs weren’t. We now know that visual information also reaches the mushroom bodies and that these regions integrate multiple sensory modalities and support cross-modal learning. Even in very well-studied taxa, we’ve repeatedly underestimated what regions are doing. (Moreover, insofar as we know what the hemiellipsoid bodies in crustaceans are for, the comparative neuroanatomy suggests that variation in their size and complexity may track the amount of olfactory input, which has nothing to do with sentience. See the end of this paper for details.) Finally, even if the hemiellipsoid bodies are small relative to our expectations, other integrative regions—like the medulla terminalis and structures plausibly homologous to the insect central complex (central body + protocerebral bridge)—aren’t obviously reduced in the same way. So, we should be wary of placing much weight on this neuroanatomical point.

Second, I worry that the post puts too much weight on that one negative behavioral result—namely, the failure to observe directed grooming/rubbing in PWS under extreme pH stimuli. First, null results in animal behavior are notoriously common. Second, there are some additional reasons for caution in this particular case. For example, the authors used extremely high concentrations of NaOH and HCl for two species because lower concentrations produced no response in preliminary trials; they also explicitly note that such pH levels may be ecologically irrelevant, which raises the possibility that the stimulus wasn’t being processed in the expected way at all. On top of that, the behavioral coding differed from the studies they were attempting to replicate: for example, they didn’t count antennae contact with the tank wall as grooming, whereas earlier work did. More broadly, directed grooming is only one possible self-protective response. In many taxa, pain manifests as withdrawal, guarding, reduced feeding, or altered exploration. Third, animals are sensitive to many kinds of damage. Even if we don’t see responses to pH, it would be shocking if there weren’t any sensitivity to mechanical injury, for instance. Taken together, this makes it hard to treat the null grooming result as a strong strike against pain-like processing in PWS.

Third, you’re skeptical that nociception plus pharmacological modulation should shift our priors much. But granting that anesthetics can suppress movement in a fairly general way, pharmacological modulation is still one of the classic tools used to distinguish mere reflexive responsiveness from centrally mediated aversive processing in animals. So I think there’s some risk of people reading the post as saying “nociceptors, therefore basically nothing,” when a more accurate characterization is that we have at least some of the kinds of markers that pain researchers take seriously in other contexts.

Finally, while you’re right to caution us with respect to extrapolating across taxa, that’s abandoning one of the only tools available in our current, data-starved situation: phylogenetic inference. Decapods probably share a lot of conserved neural and behavioral machinery, and many pain-relevant capacities—learning, motivational tradeoffs, and injury-related protective behavior—appear across the group. Given that, the default evolutionary expectation isn’t obviously that pain-like processing appears in crabs and lobsters but is absent in shrimp unless we have strong reasons to think a major functional transition or loss event occurred. And I’m not sure we do. So, yes, taxonomic differences matter, and suborder distinctions may well track meaningful neurobiological differences, but they don’t by themselves defeat inference from related taxa.

Again, none of this is to claim that the evidence for pain in PWS is already strong or that skepticism is unreasonable. Just trying to push back a little on how skeptical we should be.

Rob has a thoughtful reply here.

I very much agree. Moreover, I do not even know whether electrically stunning farmed shrimps increases or decreases welfare due to effects on soil animals and microorganisms.

I think suffering matters proportionally to its intensity. So I would not neglect mild suffering in principle, although it may not matter much in practice due to contributing little to total expected suffering.

In any case, I would agree the total expected welfare of farmed invertebrates may be tiny compared with that of humans due invertebrates’ experiences having a very low intensity. For expected individual welfare per fully-healthy-animal-year proportional to “individual number of neurons”^”exponent”, and “exponent” from 0.5 to 1.5, which I believe covers reasonable best guesses, I estimate that the expected total welfare of farmed shrimps ranges from −0.282 to −2.82*10^-7 times that of humans, and that of farmed black soldier fly (BSF) larvae and mealworms from −4.80*10^-4 to −6.23*10^-11 times that of humans. In addition, I calculate the Shrimp Welfare Project’s (SWP’s) Humane Slaughter Initiative (HSI) has increased the welfare of shrimps 0.00167 (= 2.06*10^5/0.0123) to 1.67 k (= 20.6/0.0123) times as cost-effectively as GiveWell’s top charities increase the welfare of humans.