Talking to Congress: Can constituents contacting their legislator influence policy?

Summary and Key Takeaways

The basic case: Contacting your legislator1 is low hanging fruit: it can be done in a relatively short amount of time, is relatively easy, and could have an impact. Each communication is not guaranteed to be influential, but when done right has the potential to encourage a legislator to take actions which could be quite influential.

Why do we believe that constituent communication is useful?

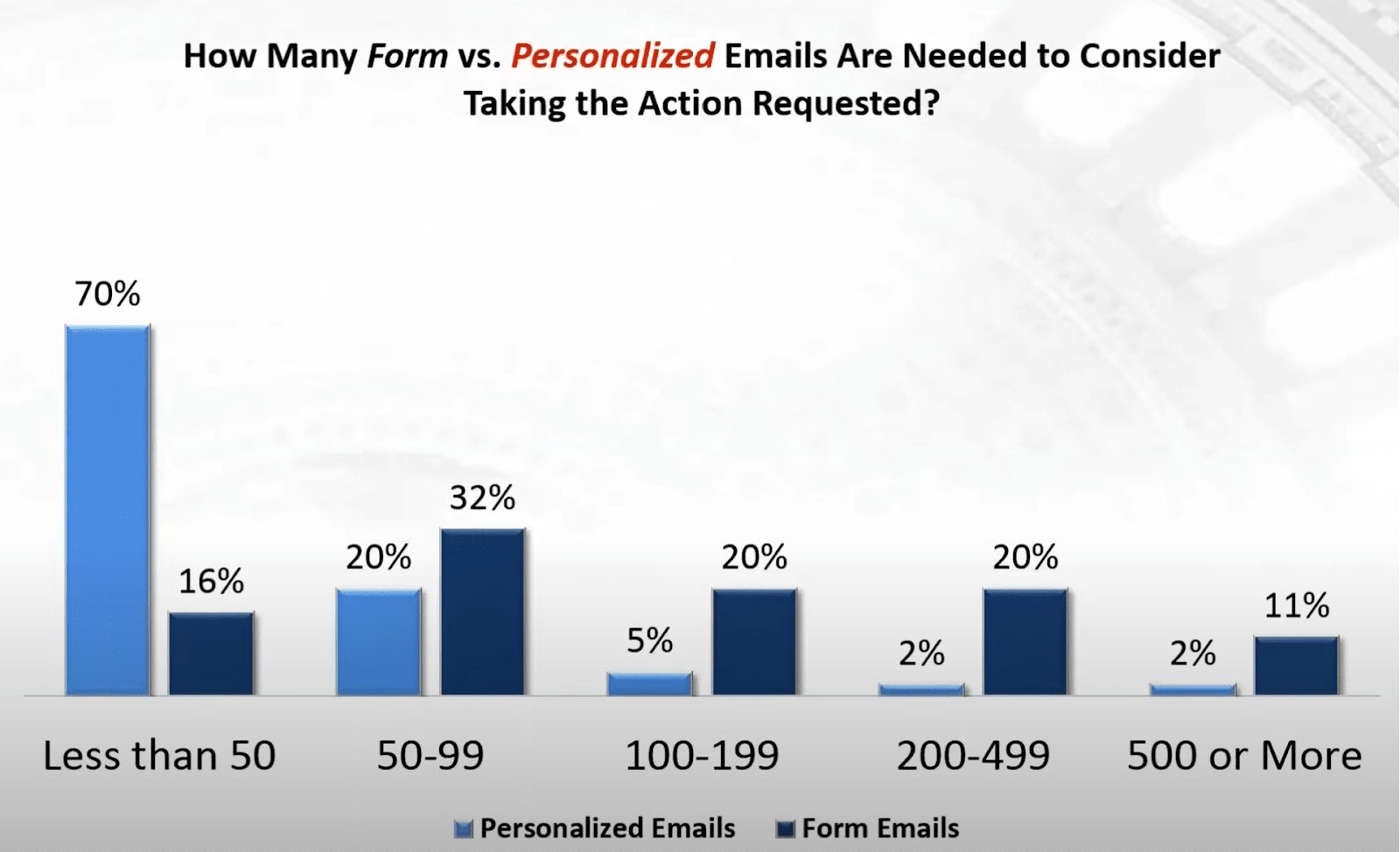

At the state level, we’ve seen two studies which have randomly assigned some legislators to receive communication[1], finding a 12% and 20% increased chance of the legislator voting towards the desired direction. At the federal level, one survey of staffers[2] indicated that less than 50 personalized messages were enough to get an undecided member to take the requested action for the majority of offices (70%).

Anecdotal accounts, both in the literature and our conversations indicated that, despite disagreement on how much impact communication has, the possibility certainly exists for it to affect what a legislator thinks.

What is the best way to conduct one of these campaigns?

Some factors are important to be aware of. Communication is best sent for issues legislators are undecided on, and to legislators with smaller constituencies. See How to Best Execute the Communication for more.

Personalized communication goes the furthest. Many advocacy groups use form email templates where you merely add your name to a pre-generated message and hit send. These might be net negative, and staffers have made clear time and again that personal messages, written by the constituent, are best.

In-person meetings are best, but letters, emails and calls are likely nearly as effective, while social media posts and messages have a more uncertain effect.

The way you frame your concern matters. You’ll have to decide whether you want to make a very specific ask to support a given bill, or want to make a more general case for concern with an issue, perhaps telling a personal story to support your position. The best messages will make use of both frames.

Know your legislators. Different legislators will have their own agendas and issues of focus[3], so being familiar with your legislator’s work is important.

Introduction

This is part of a project for AI Safety Camp undertaken to answer one chief question: can constituents contacting their legislator influence policy?[4]

In answering this question, we’re primarily speaking to two groups. First, to organizers within the broader policy/advocacy space trying to decide how to best work with Congress and if facilitating constituent communication could be a worthwhile part of that. Second, to individuals, who are concerned with the state of affairs of current risks and would like to take a further step (however small) in reducing that risk. We hope to provide below a synthesis of our findings, so that each of these groups can make a more informed decision as to whether it’s worth their time.

All in all, the below is the result of 10 discussions with current and former congressional staff, ~50 hours of collective research, and conversations with many organizations in the AI policy space. From our research and conversation with staffers, we’ve found little directly measuring the effectiveness of the method, but general agreement that it’s likely impactful given certain circumstances, and much on how it can best be executed. From our conversations with those in AI policy, we’ve found that facilitating constituent communication isn’t currently a focus for groups in the AI Safety ecosystem, but that the majority of those we’ve talked to are neutral to positive on bringing this into the ecosystem.

That being said, this post is meant to be cause-agnostic, and we plan to go into greater depth in a future post on how this can be specifically applied to AIS. If you’re interested in hearing more, please feel free to sign up to our mailing list. Do note, all opinions of the authors are their own and do not reflect their organization’s views.

Why Talk to Congress?

If you’ve been to a protest, read the news, or scrolled through social media, you have likely been encouraged at some point to call or write your legislators on a controversial issue of public debate. And if you’re like most people, you have rarely, if ever, participated. Yet few methods are as pervasive in political advocacy as constituent communication with Congress.

In the context of AI safety, congressional engagement on AI risks is unavoidable. We are already in a world where Congress is holding multiple hearings per year with frontier lab CEOs on the topic of AI risk; we do not anticipate this state of affairs to go away in the near future. The current political discourse on AI safety and regulation is dominated by a handful of executives, lobbyists, and researchers. This discredits AI safety in the eyes of many key DC insiders and potential allies who see such efforts and related policy proposals as a billionaire-backed, techno-doomist, EA-inspired attempt at regulatory capture[5]. If AI will be as transformative as many predict, we need to validate its place as a mainstream political topic. Our understanding is that many individuals writing on AI safety have traditionally expressed skepticism that the public would broadly care about the topic, and have been surprised by the level of public concern as more polling data are coming out.

The below example illustrates the change that is possible when widespread constituent communication is used to encourage congressional action on an issue the public is concerned about.

An Example

Advocates have utilized congressional campaigns for decades, often enabling policy changes that would not otherwise have occurred. One clear example of their potential comes from Fowler and Shaiko (1987):

In 1984, the House passed a bill with a large majority (323-53), providing $10 billion to clean up hazardous wastes, but the bill died in the Senate after they failed to take action on it. A similar bill was introduced in the House in 1985, this time facing steep opposition, “flatly rejected” and quickly replaced with a much weaker version. But a stronger bill did pass several months later, despite previous opposition. What changed?

The political climate shifted between 1984 and 1985. 1984, being an election year, was subject to “political forces” influencing the House vote which disappeared in 1985. But the change did not stick, as Fowler and Shaiko elaborate: “Needless to say, the environmentalists were furious. The Sierra Club quickly took action…[and their] network was activated in more than 200 key congressional districts…After five months of continuous pressure, a stronger version of the Superfund bill was passed, 391-33.”

Of note here is that the bill in question was not partisan—passing with overwhelming support from both parties—but it still took a sustained congressional campaign to ensure its passage.

Types of Congressional Communication

So how might you talk to Congress, once and if you’ve decided that doing so makes sense?

Detailed below are the major categories of congressional communication. We don’t go into it here, but if you’d like to learn more about how each of these are processed through offices, there is a well done visualization here, and we also plan to release a detailed post on the process soon.

Constituent Visits: Meeting directly with congressional staff to discuss a policy question in greater depth. These meetings can occur in the legislator’s district or D.C. office and typically last 15-30 minutes.

Emails: Likely the most common form of contact, both in the form of personal messages crafted by constituents themselves and “form” emails that are sent on behalf of a constituent by an advocacy organization that they merely have to click a button to send.

Letters: Often very similar to personalized emails, letters involve writing a personal message of concern about an issue and often asking the legislator to do something about it.

Phone Calls: Direct calls to a congressional office asking a legislator to support or oppose a given issue. These calls usually take no more than 1-2 minutes.

Social Media: This may involve “tagging” your elected official on Twitter, writing on their Facebook page, or generally posting anything on social media that is meant to engage them and convey an opinion.

Theory of Change

Our full theory of change is outlined below, with evidence to support specific connections where we have it:

Legislators are responsive to public opinion, and more specifically the opinion of their constituency.

General

“In 75% of the studies that Burstein (2003) analyzes, public opinion has a statistically significant effect on policy.”

“Both constituent opinion and objective conditions predict lawmaker behavior when the two are not aligned, but constituent opinions tend to predominate.”

“Existing scholarship has shown that constituent opinion influences Representatives’ co-sponsorship of legislation, the content of their legislative agendas (Hayes, Hibbing and Sulkin 2010) and their participation in committee and subcommittee work.”

“State legislators’ voting behavior after they’ve been informed of constituent opinion closely tracks opinion in the district.”

Some legislators are responsive because they view their job as fulfilling a delegate, rather than trustee-type, role.

“Members can often be categorized as a trustee or delegate, a trustee who has been chosen himself specifically to legislate how things appear to him (who the public have put their trust in), or a delegate who is meant to reflect as best he can the opinions of the district. Research has shown that members who identify as delegates exhibit greater policy responsiveness on salient issues and vote in line with their perception of constituent opinion more often.”

Others are responsive because failure to pay attention might cause issues for their re-election.

Legislators who depart more often from the preferences of their constituents are likely to receive a lower vote share in the next election, generating a signal of perceived weakness for future primary- or general-election challenges.

In other words, communication from constituents, and the sentiments contained within, function as a sort of threat, signaling that if the member does not act in line with the wishes of the people, voters will replace them in either the primary or general election. As a result, following the wishes of their constituents acts as a bargain for re-election.

Legislators often have imperfect views of what exactly it is that their constituents think, especially for newer or unknown issues.

“In their seminal study, Miller and Stokes (1963) found that legislators were responsive to what they thought public opinion was on various issues but their perceptions of public opinion were only weakly correlated with actual public opinion on those issues. Combined with our own results, this suggests that legislators want to act more like delegates but often fail because they are uninformed or misinformed about public opinion.”

“For foreign affairs, the correlation between actual district opinion and the Representative’s perception of district opinion is only 0.19; for social welfare, the correlation is 0.17. However, for civil rights, the “charged and polarized” issue that they study, Representatives have a much more accurate perception of constituent opinion (r=0.63).”

Constituent communication is one of the best ways to inform legislators of what their constituents think.

The majority of Americans have consistently supported further regulation of AI[6].

52% think AI should be “much” more regulated, 26% saying “somewhat” (YouGov, Aug 2023).

58% support thorough regulation (AI Policy Institute, July 2023).

79% think we need more (Harvard CAPS Harris, Jul 2023).

35% think it’s “very” important for the government to regulate AI, a further 41% finding it “somewhat” important (Fox, Apr 2023).

Across 17 major countries, 71% believe AI regulation is necessary (KPMG, February 2023).

82% think AI should be regulated (MITRE/Harris, 2022).

The majority of legislators are not supporting or investigating potential efforts to regulate AI.

This is becoming less true over time, but concern over AI does still seem rather concentrated among a small number of legislators, especially when you look for legislators that are trying to address a broad range of concerns from AI (like Hawley and Blumenthal) vs those who are drafting more narrow legislation targeting more specific risks like deepfakes.

Further constituent communication would convey constituent worry, and consequently cause more legislators to prioritize the issue.

In an experiment on a state legislature, “the legislators receiving their district-specific survey results were much more likely to vote in line with constituent opinion than those who did not.”

“Perceptions of constituent interests are ‘systematically skewed in favor of those [constituents] active in contacting or contributing to the legislative office.’”

“Staffers are more likely to identify constituent groups in the district as relevant to a certain policy when said groups have been actively contacting their office.”

Further legislators prioritizing the issue will increase the odds of regulation.

Regulation would help address AI risk.

The scope of defending this is much larger than can be addressed here and actually helping address the risk will likely be dependent on the effectiveness of specific proposals. But, given the lasting nature of policy change and the lack of fully sufficient voluntary regulation from leading labs, regulation does seem like a promising path here.

Thus, constituent communication can help address risk from AI.

Is It Effective?

In short: yes, when done in the right way.

In perhaps the most in-depth exploration of constituent communication which reviews much of the existing literature, Abernathy’s 2015 dissertation states that “members of Congress are highly responsive to constituency opinion on salient political issues.” Some of these studies have looked at the messaging as part of work by interest groups, multiple studies finding that constituent opinion can be an effective way to influence legislators, on topics ranging from confirming judicial nominees to early environmental legislation. Others have sought to execute quasi-experimental designs at the state level; a study on Michigan state legislators randomly chosen to receive constituent contact found that contact increased the probability of support for the legislation by 12%, and one on New Hampshire state legislators found a 20% increase in support for key requests[7].

Some of the literature on the effect of public opinion on legislators is also relevant here, as communication from constituents is one of the most important ways for legislators to understand public opinion. Summarizing the findings from across the literature in 2003, Burstein says: “The impact of public opinion is substantial; salience enhances the impact of public opinion; the impact of opinion remains strong even when the activities of political organizations and elites are taken into account [and] responsiveness appears not to have changed significantly over time”.

The last form of evidence to mention has come from interviewing and polling legislators and staffers to better understand their subjective sense of its effect or importance. Studies from the early 2000s indicated that citizen contacts have “a large impact on legislative decision-making”, and follow up research across the years has found constituent communication can have significant influence on issues the legislator has not decided upon. Perhaps one of the most striking findings is that less than 50 (personalized) communications can be enough to prompt the office to consider taking the requested action. Many legislators and staffers view staying in touch with constituents as a key part of their job, this importance highlighted by the remarkable amount of staff dedicated to the process in each office.

But we do wish to highlight that there’s a lack of high quality studies on effectiveness of communication at the federal level, and we’d encourage further work in this area. And we also want to emphasize that there’s some evidence that constituent communication isn’t that effective. Abernathy’s dissertation tested multiple hypotheses about factors that might modulate the effectiveness of communication, and found mostly null results. Sometimes communication just gets lost, and even when it does get logged, different mail reporting processes show that some offices don’t have effective formal mechanisms for considering communication. Others argue that the current system of communication is set up for responsiveness rather than facilitating substantive input on decision-making, where constituent opinions are turned into easily digestible, and dismissed, data points.

But the critiques above are all arguments of just how effective communication is, and we’ve yet to come across any sources that claim personal messages could have a net negative effect, and very few that claim there’s no chance of impact. All of the above critiques focus on the formal system of consideration, and don’t address the potential for the emotional impact (storytelling) frame which carries at least some possibility of impact outside of the form system. All in all, counterarguments might update you towards being skeptical of significant time investment in such a project, but seem unlikely to make quicker actions like emailing your legislator and asking them to support a specific bill a poor use of time.

So you’ve communicated with your member, now what happens? We’ll bring up other aspects where relevant, but if you’d like to understand more about how congressional offices process constituent communication, please see our companion post. The process is also outlined here.

How can you best communicate?

How Do You Frame the Issue?

The framing of any given issue—the lens through which constituents or policymakers approach the issue—is crucial. We’ve generated a number of general points on frames below, but do keep in mind that another crucial aspect of framing will be fitting it into a specific policy context, so this set should be viewed as an incomplete set of recommendations.

Receptiveness to a given frame varies widely among Congressional offices. Some policymakers are highly receptive to some frames and others to different ones. (For instance, Legislator A might care primarily about misinformation, while Legislator B might care primarily about job loss). Whatever the focus may be, make sure it’s clear.

One popular frame is telling a story, which can be particularly impactful and make your message stand out. Staff processing constituent communication have said that “telling a story is the most effective way of getting attention.” Intra-office practice reflects this: staffers often collect “unique, moving personal stories” for Congresspeople to read and respond to directly. If you want your elected official to see what you’ve written, a memorable message is your best bet.

How to Best Execute the Communication

You and your message should be easily identified and categorized. Offices will first verify that communications are from real constituents[8] and sort your message according to your ask.

In the formal process of incorporating constituent communication, messages are primarily datapoints for offices to make decisions, rather than mediums for direct persuasion. Your message should be easy for a junior staffer to summarize to their boss in the event that your issue is of interest (either because of constituent messages or separate internal conversations). Anything that makes information sharing more difficult—the length of the message, a hostile demeanor, multiple asks, etc. - should be avoided.

The best practices for messaging primarily involve clarity and conciseness:

Ideally, make a specific request regarding current legislation (including bill number[9]) and include a personal story relating to the issue.

Stay on topic throughout the message or meeting, ideally just focus on the one request.

Emphasize constituent support through national polls or any relevant local data available.

Include expert information demonstrating the impact of the issue, especially anything unique to your Congressional district if applicable.

Indicate you know the member’s current position.

Familiarize yourself with an individual congressional office’s schedule.

Be polite and thank congressional staff for their time. Positive feedback is rarely sent but often well received.

Honesty is good, don’t feign interest in an issue for other motives.

There are a number of logistical best practices as well:

Messages

Provide sufficient information to verify that you are a real constituent if it’s not requested already (specifics requested may vary depending on the office)

Include an indication of whether or not you’d like a reply.

Calling

If leaving a voicemail, send a follow up email with your request in writing.

Meetings

Make the request two to four weeks in advance.

Include all the information the Scheduler needs:

Meeting topic or reason for the meeting

Primary contact’s name

Name and short description of the group

Requested meeting date

Primary contact’s email address

Try to include visual materials which show the impact on the district or state.

Leave behind a 1 to 2 page summary of the issue and your stance (94% of offices find it helpful) or send a follow-up email with attachments (86%).

Send a thank you message and keep in touch with the office. This helps build a relationship, which can potentially enable further impact in the future.

There are also other various factors to consider when sending a message, which can also modulate the effectiveness of the communication along with the factors mentioned above:

Messages should be focused on issues for which the member is undecided.

Legislators exhibit higher levels of responsiveness as their next election nears.

Messages should be sent well before the vote on a bill to allow time for processing.

More competitive districts are more responsive to constituent opinion and conversely, more secure members are less responsive.

Junior members are more likely to pay attention to constituent opinion.

Redistricting makes members more responsive to the opinion of their new constituency.

Members with greater volumes of contact, either due to the size of their constituency or their fame nationally, tend to adopt less inclusive correspondence systems.

Traditional partisan messages should be avoided.

The Importance of Personalized Messages

A key takeaway from our research and discussions with advocates is that the more personalized a message, the better. As much as 90% of the communications legislators receive are template letters, pre-written messages which only require individuals to add their name and are often sent en masse, but there’s reason to believe these aren’t as effective as personalized messages that have been crafted entirely by the constituent.

Personalized messages demonstrate the strength and seriousness of constituent belief. Multiple studies have indicated that, in the absence of more direct information, legislators use the amount of effort required to communicate as a proxy for constituent concern.

This doesn’t just increase the chances your message is taken more seriously, it also increases the odds that your message is read by the legislator themselves. As one staffer put it, “the more effort a constituent puts into their correspondence with us, the higher the likelihood the Member will respond themselves.” You can see the clear preference for personalization in the image below:

Personalized messages also have the benefit of demonstrating diversity of constituent opinion: form letters all giving the same reasons for AI safety will likely have less impact than personalized letters written from different perspectives explaining why constituents care about the issue. And since different legislators are receptive to different arguments on AI risk, it is valuable for a campaign to introduce multiple such arguments and find what resonates.

The Importance of Coordination

There are two types of coordination worth discussing here: 1) coordination of communication, and 2) coordination with other strategies.

If you’re able to get multiple people to write to the same legislator about an issue, is it better to send messages close together in time, or to spread them out? Congressional advocacy campaigns traditionally try to concentrate their communication in a specific time period, which makes sense given current office practices for processing constituent communication, which see issues get batched together. Staff reports on communication often focus only on the “top” issues of the time period[10], i.e. which issues generated the most constituent messages in a given period.

Congressional practice indicates that, insofar as you hope to facilitate this, you might want to implement something similar to current practices of alerts or notifications that encourage people to send messages in rough unison (within the same week is a fairly safe bet). That being said, communications that aren’t batched together can still contribute positively, but for this you’ll be better off to focus on sending higher quality, emotionally appealing messages that are more likely to move the junior staffer reading it; multiple staffers have told us of processes for moving compelling, personalized messages up the chain outside of the mail report process.

Constituent communication can also be combined with other advocacy strategies, like traditional lobbying. AI companies are already beginning to lobby Congress, and if the AI safety community doesn’t engage in congressional meetings, we are essentially ceding this ground to lobbyists from said companies. However, if we do engage in congressional meetings without demonstrating constituent support, we are likely to be dismissed as outsiders with irrelevant concerns.

It is therefore important to pair lobbying with grassroots congressional communication. The “outside game” of constituent communication provides a basis of constituent support which can then be channeled by the “inside game” of direct lobbying into a more in-depth discussion of AI risk and potential policies to address it.

Various studies have found that this sort of pairing of direct lobbying and constituent communication often used by interest groups is an effective combination. We haven’t yet encountered any definitive evidence on how these strategies are best paired, but it seems like the best approach may be to facilitate constituent communication first, in order to lay the groundwork for further “inside game” progress[11].

What Form of Contact is Best?

The specific type of message matters much less than whether the message was personalized. The difference in effectiveness between e.g. in-person meetings vs. letters is small compared to the differences between personalized and form communications more broadly.

In-person visits seem to be the clear frontrunner across sources, so if you are able to visit your legislator’s DC or district office, this is likely the most effective single strategy. But a combination of strategies also seems desirable, and your best bet may be to maintain communication with the office over time, employing multiple tactics as the issue sees further development.

In-Person Visits

As put by one staffer: “the truth is that more weight is given to groups of constituents who show up in person. I hate to say that people have to fly across the country, but it really does have more of an effect.” Surveys reflect the importance of this form. Staffers were asked what influence an in-person visit from a constituent would have on an “undecided lawmaker;” 99% responded with “some” or “a lot” in 2004, 97% in 2010. Furthermore, a 2013 survey found 95% view in-person visits as “somewhat” or “very” important for developing new ideas for issues and legislation.

Email & Letters

Early work by the Congressional Management Foundation (CMF) focused on email and letters, and, when personalized, these are consistently found to be effective methods of contacting Congress. Likely anyone contacting Congress will want to use one of these as part of their strategy—most likely email for its convenience, but handwritten letters can be emotionally appealing and tell a compelling story.

Social Media

The benefits of social media are less certain. There’s evidence that social media is not very likely to matter to legislative offices, as well as evidence that it can be quite influential, making it the most contested form of communication.

The case for social media being important:

In a 2015 survey of staffers, 35% indicated that fewer than 10 social media posts were enough to get them to pay attention, with 45% indicating it takes between 10 and 25.

A 2014 survey found 75% of staffers agreeing that social media communication from multiple constituents “affiliated with a specific group or cause” would have “some” or “a lot” of influence on an undecided member.

Staffers have said:

“It’s definitely much easier/better to reach us on social media but we don’t want to tell people this because we’ll get bombarded, and we don’t quite know how to handle that.”

“Our boss looks at Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc., all the time. He sends staff screenshots of things to respond to and uses it to get a sense of what people in his district are talking about.”

The case against social media:

A 2017 survey found “social media engagement is handled inconsistently and doesn’t yet translate to the same formal tracking as other channels.”

Others have noted social media communication is almost never logged into the CRM, as it’s processed by different staff in the office than those who process the rest of constituent communication. This indicates a low likelihood that these messages or posts make it further up the chain of command (as they likely almost never make it into staff reports on the volume of communication[12]).

Staffers have said:

“We don’t track any of the contact that we have with people online.”

“Comments from social media are tracked, but I’m not sure who ultimately ends up seeing this or if/how that info is used.”

Conclusion

Our main goal in writing this post has been to demonstrate that talking to Congress is useful, and that certain types of congressional communication can be high-impact. And while the above was written to apply across risks, our project did set out to specifically address AI risk, and we wish to reiterate that we think the space would be better with further facilitation of communication. Given public support for regulation, and recent major events such as the UK AI summit, the EU AI Act, and the Biden Administration’s Executive Order, we think this moment is a window of opportunity to begin making use of this tool. Our hope in publishing this article is to help facilitate this going well for anyone in the advocacy space that’s concerned about the risks that affect us, and we’d be happy to share further thoughts if anyone is interested, especially with deployment in the AI policy space.

As we continue our project, we hope to develop a website making it easy for interested citizens to share their concerns on AI with their elected officials. If you are concerned about AI and want to keep abreast of future campaigns, please join our mailing list.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Nell Watson, Koen Holtman, En Qui Teo, Remmelt Ellen, Chris Leong, and Jacob Kraus for feedback on the project and special thanks to Christopher Negri for earlier collaboration.

Further Points of Investigation

Other levels of communication

Foreign Governments: How can what we’ve learned here be applied to foreign governments?

Congressional Committees: There are staffers for various congressional committees that might have some capacity to receive messages, but to what degree they actually listen or have the capacity to adequately process those messages is not immediately clear.

Executive Branch Requests for Comment: Most replies to RFCs seem to come from experts or groups, but there doesn’t seem to be anything barring an individual from submitting commentary; the question is just one of impact, and how much a person’s voice might matter as an individual citizen.

State Legislatures: How much does what we’ve found apply here? Are there differences in state legislatures that are relevant in considering how impactful contacting them will be (e.g. New Hampshire’s is quite different from Michigan’s).

State Executive: There are pathways to contact state attorney generals on issues; attorney generals do often carry significant weight at the state level, and perhaps don’t receive much in the way of communication, so this could be quite effective.

Other relevant methods of communication:

Town Halls: these seem quite impactful, and constituents can both attend them and play a role in setting them up and executing them by working with a local organization

“Town hall meetings are probably the most directly impactful for individual constituents to communicate with the Senator and I’m not sure people typically understand the impact that their presence and comments can have.”—Senate Communications Director

However, it is also worth noting that selection pressures from past groups using this mechanism (e.g., Indivisible) has led to fewer and more-tightly-managed town halls.

Improving constituent communication at a system level:

Should we perhaps return to a “right to petition” as a formal mechanism that the government had to be accountable to, as once was the case in the past?

There’s an opportunity for technological innovation with CRMs that could make a real difference for Congress. Many complain about current CRMs and the state of the system is such that voices are often lost within the system, a breakdown of the democratic process. Thus, a technological solution that could balance making tasks more efficient while also making sure that constituents aren’t just turned into data points, could prove impactful.

Another approach that might make sense would be to increase funding for offices to better address the increased volume of constituent communication over time.

Further reading:

Constituent Communication in Representative Democracy: Testing Platforms for Deliberation in the U.S. Congress: tests out a week-long online forum for facilitating communication

POPVOX might be worth looking at here, as a technology platform

Paradoxes of Public Sector Customer Service: could be useful in understanding the relation between offices and constituents better, but also seems to be more aimed at reforming offices

- ^

Here the communication was emails.

- ^

Staffers refers to all of the staff that are employed in congressional offices.

- ^

A quick way to get a sense of areas they care about is to see what committees they serve on.

- ^

Here we focus on the US context, and though our work has indicated similar lessons likely to cross-apply to other, similar democracies, we think there will sometimes be relevant differences.

- ^

We are reporting, not endorsing, this viewpoint.

- ^

You don’t have to have majority opinion on your side to make a difference, but it does help given that you might need to hit a critical number of communications, or make sure the message is perceived as widely held, to make a difference on a given legislator’s opinion. We’ve also put AI in here as it’s our focus, but the more general version would just be “a majority of constituents are in agreement on X issue”.

- ^

Namely, to not table the bill, and to pass it.

- ^

You should only contact your own representatives. A legislator from California is unlikely to listen to a constituent from Michigan.

- ^

Other informational content is likely helpful but not necessary, like including the bill status.

- ^

2% compile them on a daily basis, 66% weekly, 5% bi-weekly, 7% monthly, 1% annually, 9% “as needed”, 2% at random intervals, and 8% never.

- ^

Though it would be ideal to have the issue currently seen as important in the office when conducting further lobbying, so likely you’ll want such methods to also occur concurrently with any inside game efforts.

- ^

Though it is worth noting that at least some offices have processes for social media, one staffer saying “social interactions are tracked manually (but not in our CRM) and included in weekly press reports”.

- The Center for AI Policy Has Shut Down by (16 Sep 2025 17:33 UTC; 122 points)

- The Center for AI Policy Has Shut Down by (LessWrong; 17 Sep 2025 11:04 UTC; 95 points)

- Is Pausing AI Possible? by (9 Oct 2024 13:22 UTC; 89 points)

- How Congressional Offices Process Constituent Communication by (LessWrong; 2 Jul 2024 12:38 UTC; 30 points)

- Explaining the Joke: Pausing is The Way by (LessWrong; 4 Apr 2025 9:04 UTC; 25 points)

- How Congressional Offices Process Constituent Communication by (2 Jul 2024 12:38 UTC; 20 points)

- OpenAI defected, but we can take honest actions by (21 Oct 2024 8:41 UTC; 19 points)

- OpenAI defected, but we can take honest actions by (LessWrong; 21 Oct 2024 8:41 UTC; 17 points)

- Writing Your Representatives: A Cost-Effective and Neglected Intervention by (9 Nov 2025 1:33 UTC; 14 points)

- 's comment on Emergency pod: Judge plants a legal time bomb under OpenAI (with Rose Chan Loui) by (8 Mar 2025 20:05 UTC; 6 points)

- Some reasons to start a project to stop harmful AI by (22 Aug 2024 16:23 UTC; 5 points)

- Some reasons to start a project to stop harmful AI by (LessWrong; 22 Aug 2024 16:23 UTC; 5 points)

- 's comment on Ozzie Gooen’s Quick takes by (28 Jun 2024 16:57 UTC; 3 points)

- Nationwide Action Workshop: Contact Congress about AI safety! by (24 Feb 2025 15:12 UTC; 2 points)

Setting up an AI Safety Institute might get discussed in Australian Parliament because I sent approximately 15 emails and had two meetings. I’d guess about 4 hours of work.

Sorry I must have missed this earlier, but yeah we linked to your shortforum in the post, a really great example of the positive upshot of doing this sort of work! Have you done any writeups on how you went about the meetings yet? Feels like that might also be worthwhile.

Ah, I missed that. Yeah I might do a write up :)