A note for EA Forum: While the issue of men’s health isn’t perhaps a high priority in terms of Effective Altruism, it’s worth thinking about how many of society’s problems are caused by anti-social male behaviour. This post explores the issue under the guidance of experts and offers some solutions.

HOW THIS POST CAME ABOUT

When I put a call out for non-zero-sum topics from subscribers, it was my brother who first replied with masculinity—pointing me to the work of author Richard Reeves.

“I think the danger of zero-sum thinking is present … men are suffering because women are rising. But it’s also true—when I try to persuade policymakers to do more stuff about boys and men, they’ll say No, no, no, it’s women and girls who need help. No, no, they both need help.” — Richard Reeves

I had also been listening to Scott Galloway echo many of the same sentiments. This seems to be part of a more healthy discussion around masculinity—a counterpoint to the toxic extremes of the Manosphere.

“We’ve conflated toxicity with masculinity” — Scott Galloway.

This post is far from a comprehensive analysis of the issue, but I have followed the guidance of experts; Reeves, Galloway, and Christine Emba—whose work I recommend for a deeper dive. We will, as always, explore the issue from a non-zero-sum angle—looking for win-wins.

MEN’S… RIGHTS?

I have to admit, I haven’t taken an interest in “men’s rights” until now, because of the way I had experienced the subject being represented, in the past, by Men’s Rights Activists — promoting a traditionalist model of masculinity, while emphasising their victimhood, in a world where, as a man, I personally felt I still benefitted from many advantages, and saw the women around me still facing barriers I did not. But I have now found my dismissal of the issue may have been misguided.

THE PROBLEMS

There are numerous reasons to rescue masculinity from toxicity, after all, men cause a lot of problems for everyone through anti-social behaviour (this is, by no means, an exhaustive list).

MEN ARE…

Men are a group that poses risks to society, and yet they are an at-risk group themselves.

Scott Galloway points out that, if this was any other group, we would talk about it in terms of needing better social programs and empathy. But a call for empathy can seem like quite an ask for those who are the victims of male anti-social behaviour. However, as we will explore, empathy is not a reward for bad behaviour but the key to preventing it—that is, when it is adopted by responsible people.

“If responsible people don’t address real problems in a straight forward way, irresponsible people are going to exploit them.” — Richard Reeves

EMPATHETIC MANFLUENCERS?

When journalist Christine Emba, author of “Rethinking Sex: A Provocation”, interviewed young men about what they gain from those she terms ‘Manfluencers’ such as Jordan Peterson, Joe Rogan and Andrew Tate, she too found the resounding answer was “Empathy”.

I am hesitant to put Peterson, Rogan, and Tate in the same category (Manfluencers) because I think they all have very different approaches and effects; Jordan Peterson focuses largely on self-improvement, taking personal responsibility and conservative values, Joe Rogan is a more liberal voice who can at times be very insightful and at other times go bonkers, while Andrew Tate is at the extreme end of the misogynist spectrum.

However, they do share one commonality. Emba points out that ‘Manfluencers’ not only offer empathy to alienated young men but they speak about masculinity in aspirational terms; as a right of passage, a challenge or a summit to be met physically and mentally.

“… and these guys are cheering them on, and that’s appealing” — Christine Emba

Emba warns that this vision of masculinity has a significant downside—in that it is often placed in opposition to femininity; from blaming feminism, female agency and women’s studies to excusing rape and taking part in sex trafficking.

“What is it exactly about ‘Women’s Studies’ that you believe is fostering revolution?” — Joe Rogan questioning Jordan Peterson

It’s a very exclusive, zero-sum conception of masculinity.

IT DOESN’T HAVE TO BE A ZERO-SUM GAME

There is zero-sum thinking on both sides, both from the toxic masculinity side and from the mainstream.

“People see it as a zero sum game where, if you feel empathy for men, it must mean that you are anti-women. And so there’s a lack of empathy and what I call zero-sum gaming it, you know, Civil Rights didn’t hurt white people, it helped them, Gay Marriage doesn’t hurt heteronormative marriage, it enhances it. So, to talk about empathy for young men is in no way, and should in no way be seen as, anti-women.” — Scott Galloway

BUT CAN WE FOCUS ON EVERYONE?

I actually had some trouble reconciling this idea. Because the question immediately occurred to me—if we focus on men as well as all the traditionally vulnerable groups: minorities, women, the poor, children, the LGBTQ community, aren’t we then just focusing on everyone? And therefore not actually focusing on anyone?

But the programs initiated to focus on a particular demographic aren’t just one-size-fits-all line items in a government budget that simply give an advantage to that group. Policies that focus on particular demographics do so by helping that demographic deal with their particular struggles. If one demographic is struggling with poverty, then that becomes the focus of their program, if another is struggling with safety, or imprisonment, or rights, or representation then that becomes a focus of their program.

“Let’s do ourselves the favour of assuming we can think two thoughts at once” — Richard Reeves

Men’s issues can be approached in the same way. Men might not need preferential quotas or scholarships for university, or abortion rights, or greater representation in government. But they might need more exposure to male teachers in primary school, access to apprenticeships or prison reform.

POLICIES FOR MEN CAN BENEFIT ALL

What’s more, these programs can benefit everyone. My daughter, for instance, at 10, has her first male teacher—his tone, approach and energy are different, and my daughter is benefiting from that. Greater diversity in primary education is a benefit to all.

There is also the benefit of having well-adjusted men in society, which is essential to a functioning system—because we’re a real liability otherwise.

“Women are, I think, ready for more economically and emotionally viable young men. Women are dating older and older, because they’re having trouble finding what they would perceive as viable young men.” — Scott Galloway

“A world of floundering men is very difficult to imagine as a world of flourishing women, or vice versa and I think that was one of the central insights of the Women’s Movement.” — Richard Reeves

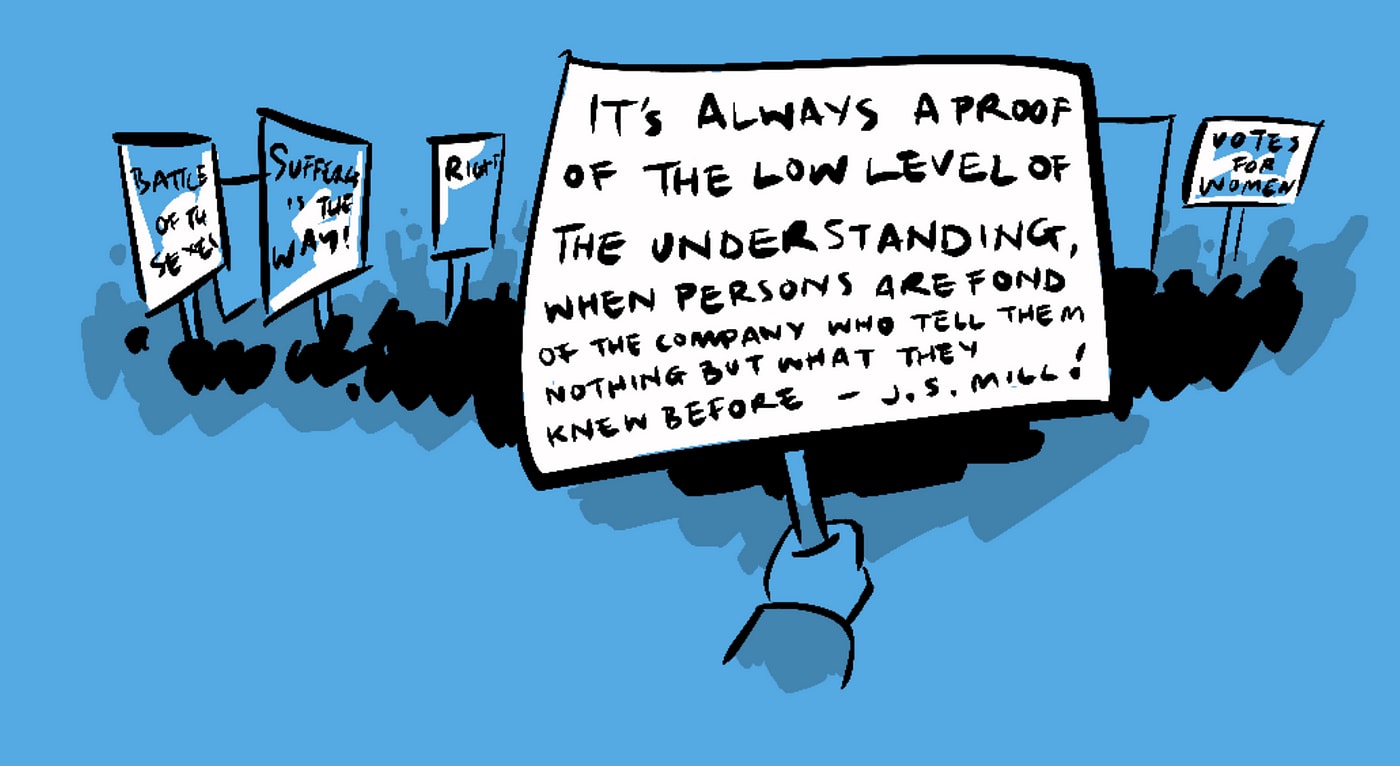

John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor Mill, in their feminist treatise “The Subjection of Women”, made the case, to men, that by denying women education, they were condemning themselves to life-long relationships with uneducated wives, who they will find dull and uninteresting. Now we are faced with the opposite situation, with men falling behind academically and retreating to the online world of video games and pornography.

Mill’s argument could be reprised today—partners thrive together, and if one is addicted, depressed and withdrawn or worse, that’s no good for either.

Mill’s insight was that for men to be strong doesn’t mean women have to be weak. In fact, J.S Mill proposed that the inclination to limit women’s education resulted from a weakness in men—a fear of being challenged. The fact is, strength begets strength, stronger men and women urge each other on to reach their potential.

“If we want our society to survive and flourish, both sexes have to be doing well.” — Christine Emba

COURAGE IS THE SOLUTION

Galloway takes the view that masculinity is a construct made up of different elements, each of which can be positive or negative, and can be adopted by anyone of any gender. He talks about reclaiming the term masculinity with a focus on the positive aspects.

Christine Emba too thinks we need to a positive vision of masculinity but…

“… not one that says Well men, to be non-toxic you need to be more like women.” — Christine Emba

Emba’s research found that strength, leadership, responsibility, self-mastery and care for others were positive traits that men associated with masculinity. She believes we should shape a pro-social vision of masculinity around these values.

There can be an issue with these traits though. Many have a dark side; strength can be misapplied as aggression, leadership as dominance, and self-mastery as narcissism.

But there is one characteristic that is safeguarded against this dark side. The key characteristic that encapsulates positive pro-social masculinity is courage—let me explain.

RISK-TAKERS

Males are statistically less risk averse, which can make us do crazy things, but also noble, selfless acts. Men are more likely to risk their lives in battle or crisis and, in particular, are more likely to do so for a stranger. These heroic acts of courage are an affirmation of masculinity no amount of lamborghinis or Rolexs can amount to.

But how often are we faced with such a situation; a test of our courage or demonstrate our bravery?

Barely ever, right?

SURROGATE COURAGE

We can, however, play a gun-toting hulk in a video game, we can floor it in our sports car around a bend, we can posture and pose in front of women, or worse, intimidate them with aggressive behaviour. These actions give some of us a taste of risk-taking, but these risks are empty, they’re not courage—courage is risk-taking for what is right.

“Positive masculinity means using traits that feel distinctive to men for the good of others.” — Christine Emba

COURAGE TODAY

A courageous act today might be speaking up in a meeting in support of a colleague when it would have been easier not to, or to tell someone how you feel about them—how they hurt you or how they made your day. Courage might be saying “I’m sorry”, or perhaps letting go of your self-consciousness long enough to really hear someone else. It could be calling out racism, sexism or homophobia, or it might be stepping in to mediate when an argument gets heated.

These acts are difficult, embarrassing or potentially dangerous but they are courageous, and doing these hard things with consistency will make you feel more like a master of your own will, more of a leader and more masculine, regardless of your gender.

I want my daughter to have this sort of courage, and for any men in her life to have it too (including me).

SO…

There is a problem with men, at present, that is causing problems for everyone. It requires the empathy and the attention of responsible people. But at the same time, this focus on men need not be at the expense of other groups—in fact, particular measures that will help men, can benefit all.

It is ultimately the responsibility of men to solve this issue, to be better, to change—not by turning away from masculinity but by embracing a more pro-social masculinity, which can be found in courage.

New voices like Reeves, Galloway and Emba are proposing a non-zero-sum perspective that draws attention to and encourages the positive aspects of masculinity. In doing this, they are exhibiting the very courage we need—to speak up in a difficult conversation and push it in a positive direction.

Opportunities to exhibit courage may be different today, but I think courage is a positive attribute that all men can agree is important to their sense of masculinity. It is also somewhat protected from the extremes because it is, by definition, something we exercise in the interests of others and is therefore pro-social. Courage is non-zero-sum.

I want to thank my brother Nick for his idea to explore masculinity and for his collaboration with this post. It has been heartening to explore the new voices in this space, and makes me hopeful for the future. Love you bro :)

RELATED MATERIAL

My brother Nick Brown knows a lot about masculinity, he is, after all, a drummer in a band. Check them out — musical wizardry combined with lyrical hilarity.

The quotes from Reeves, author of “Of Boys and Men”, come from a panel discussionwith other experts in the field.

Scott Galloway’s quotes are chiefly from his appearance on the Rich Rollpodcast.

Christine Emba’s quotes are from Big Think.

I have made some claims relating to Andrew Tate in this article without sources, this is not because there are not references available, but rather that I do not want to be responsible for sending anyone in his direction.

Hi! I haven’t had a chance to read your article yet, but I wanted to let you know that I love the images you’ve used in your post. Did you make them yourself?

Thanks, yes, I draw them myself on an iPad, lots get recycled when they are relevant to new posts but I usually do 3 or 4 new sketches per post. It’s my little push back against the generative AI Revolution

nicely done mate!

Your point about zero-sum games is particularly interesting to me. The typical argument in the circles I run in is that we’re better off spending our resources on eliminating patriarchy, because it’s the major cause of masculine issues. The general theory of change there is that patriarchy creates a system that lies to men about things they’re entitled to (power, respect, sexual partners) but can never actually deliver on those promises; weakening patriarchy comes with a period of upheaval & reaction (we are here) where men struggle to adjust their expectations. If true, higher rates of male despair & dereliction occur because coming to terms with this betrayal is emotionally difficult. (FWIW, I am presenting this view in neutral terms but I generally believe it).

I also don’t believe that my ideal future genders terms like ‘courage’, just as much as it doesn’t gender terms like ‘care’. This just seems antithetical to removing those barriers. But I am on the extreme end of gender abolition, so I don’t want to revolve my point around this.

In particular, this world model contends that attempts at ‘positive masculinity’ have to compete with people who can just lie. These kinds of grifters survive in the market because (a) there are always new grifters with untested track records and (b) there are always new young men who haven’t learned not to trust them. Any attempt at positive masculinity therefore must promise things to men that grifters can’t also claim, which, in these terms, is to reveal that they have been betrayed by patriarchy and that they should work on dismantling that system rather than climbing or withdrawing from it.

I don’t like Scott Galloway’s take on this in particular, because he just says ‘someone should do something about this’—but without getting your hands dirty, you won’t realise that the reason there aren’t ‘positive masculine’ role models is because they keep getting outcompeted in the market by liars.

Believers of this world model would advocate for two things to happen in the world:

‘Positive masculinity’ types to focus more on helping men adapt to and cope with this betrayal

To continue to weaken & dismantle patriarchy and focus on debunking these kinds of lies

For anyone interested in following this more, I really like Shaun’s 40-minute video on the topic. I feel like, for me, it hit these points with an unusual clarity.

A really interesting comment, you’ve obviously had some experience thinking about this from a different angle to me, but nice to see we agree on the positive masculinity types.

Patriarchy: Strangely enough the idea of patriarchy didn’t even occur to me while writing this, which is a bit of an admission, as it’s obviously relevant! I hadn’t conceived of a male-initiated down-with-the-patriarchy movement, but it makes sense, when you point to the way in which patriarchy manipulates the expectations of young men, which inevitably leaves them disappointed and vulnerable to radicalisation.

Gendering ideas: I tend to agree with you, and it was a concern while writing. My reason for going along with the gendering of courage (although I do at three points mention that women also have these attributes) was that I am trying to get at the issue of men who find their masculinity very important, and perceive that it’s being denied them, or stripped away, outlawed. By recognising the positive aspects of masculinity, and not denying it I hope not to alienate those who I most want to reach.

Getting outcompeted by liars: I hear you. I may be yelling into the wind, but hopefully if enough of spout enough sense we can drown out the anti-social voices. Or perhaps, if we keep discussing these things we’ll come up with more effective argument and convince them with reason… (wishful thinking I know).

Thanks for your critique, I appreciate you helping me hone my ideas and bringing other important pieces to the puzzle. I will check out that video :)

Earlier in the article you reject the idea of telling men to be more like women, but I don’t see how ‘telling someone how they hurt you’ can possibly be regarded as a distinctively manly virtue—we’re trying to produce a substitute for cavalry charges and fighting wolves and crewing a Ship of the Line here! People wouldn’t regard a women mediating an argument as behaving in a manly way—in fact it seems somewhat feminine to me—so I don’t see how it can be distinctively masculine.

To produce a modern positive conception of manliness, I think you need to start from a place of thinking about awesome things men do and then think about how to make them more accessible and how to stop undermining them. This article feels more like you are trying to take a list of things you like and find a way to call them masculine.

It’s also not clear to me that courage doesn’t also have a dark side—just being courageous doesn’t seem like it has any guarantee that the side you support is the right one. Wars are fought by courageous soldiers on both sides. I do not buy your argument that ‘by definition’ courage is pro-social unless we are going to totally gerrymander what courage is.

Fair points.

To me courage is doing what you’re afraid of doing when you know it’s the right thing to do. It has a two-fold definition that protects it somewhat from abuse. Strength for instance does not have this additional aspect. Now, I agree it can go wrong if someone has a flawed idea of what is right, but that’s an additional issue that’s complicates literally everything—if something had to be immune to a flawed sense of right and wrong then nothing would pass that test. Courage at least requires good intent, and it furthermore requires something difficult, so it guards against convenience too.

I agree, though in my defence this is exactly what I was trying to do, pointing out men’s risk-seeking nature and their ability to do courageous things, as a major positive and trying to apply it to a world where opportunities for exercising courage are different.

Given the world we live in, courage—doing the hard thing when it’s the right thing to do, does play out in workplaces and homes, it can play out in physical exploits too (perhaps I could have talked about the thriving rock climbing community of which I am a part) but if you try doing the hard thing for the right reasons even in those mundane situations, I can assure you, from experience it does make you feel more masculine. In saying this, of course (and I clarify this 3 times in the post) courage is not the sole purview of men, women do courageous things all the time—but I think all men can agree that if there is such a thing as masculinity, courage is a significant part of it.

I disagree that saying someone hurt you can’t...

I can only say that, from experience, there is a distinctively masculine experience that a man has when they are honest despite their pride or habits. It is the same act—doing the difficult thing—that running toward enemy fire is, and takes a lot more courage to do than the simulacra of courage we take part in when playing Call of Duty for instance.

Exhibiting genuine courage in a different environment, with different variables is not about re-defining courage, it’s about finding what that very same courage means in a new context.