Why scale is overrated: The case for increasing EA policy efforts in smaller countries

Estimated reading time: 40-45 minutes

-We would like to thank the following for their excellent feedback and guidance throughout this article, in no particular order: Samuel Hilton, Haydn Belfield, Rumtin Sepasspour, Aidan Goth, Gabriella Overödder, Marcel Sommerfelt, Konrad Seifert, Max Stauffer and Tildy Stokes.

1. Introduction

This article is co-authored by five members of Effective Altruism Norway as a follow-up on our previous forum post: Objective of longtermist policy making. In the current post, we argue that the EA community should invest in expanding the geographical footprint of EA policy efforts beyond current projects which are mainly focused on the US and UK. We list a range of potentially promising geographies, including emerging countries; multinational organizations; mid-tier geographies; and small, well-governed countries.. Furthermore, we present a case study on the Nordics, covering a range of areas for potential EA-aligned policy impact in the Nordics. This does not reflect a belief that the Nordics are uniquely well suited for EA efforts. We have chosen this region because we know it well, and we fully agree that there are other regions/countries that also are suitable to similar EA policy efforts.

The main hypothesis underpinning this article is that while there is some variance in the EV of policy projects across geographies, there is a relatively broad range of geographies where additional policy efforts could be impactful. Additionally, one can expect a strong “home turf advantage” for policy makers and policy advocates—a lot of the impact potential in these careers relate to your local professional network and cultural understanding—therefore, the key question that funders should ask to determine “where should I invest in additional EA policy projects” is “where is there best access to additional EA policy talent?”. This is the question we attempt to answer throughout this article.

The main ideas in this article are based on the following premises:

The EA community’s policy efforts have been mainly concentrated in the UK and US.

Most career advice for political work in the EA community points people towards working in the world’s most influential and populous countries, primarily the US and China.

EA policy efforts could have a bigger global impact by adjusting its portfolio to include a broader set of economies, with a bigger focus on certain smaller countries to utilize their relative advantages that are missing in the larger countries mentioned above.

We especially consider countries that are well-functioning, high trust societies with a global reputation for good governance. Examples include the Nordics, Singapore, Switzerland and New Zealand.

Although the primary focus of this article is policy efforts in the Nordics, many of the benefits we discuss could also apply to other countries with certain similar traits. For instance, New Zealand, Singapore and Switzerland all have small populations and favorable ratings in metrics such as PPP-adjusted GDP per capita, life expectancy and income equality. Some other features of the Nordics that make them advantageous targets for testing EA policy ideas are their strong social safety nets, strong government capacities and low social complexities.

EA policy efforts in these countries could complement efforts in larger countries in three ways:

By experimenting with policies with uncertain impacts to see which work and which don’t work

By showcasing a successful template of a policy, and thus help lobbyists in larger countries advocate for that policy

By mobilizing national representatives (e.g. diplomats) from the smaller countries to champion EA policy efforts on the multinational level

These three bullet points are all underlying mechanisms of policy diffusion, i.e. the process in which policy decisions in one place influences policy decisions made elsewhere, often leading to the spread of policies between countries.

Successful EA policies in smaller countries can be the origin of policy diffusion of EA policy ideas to larger countries. Even though the direct impact of policy efforts in smaller countries might be insignificant on a global scale, it can have a long-lasting positive influence on other countries through policy diffusion. The idea of targeting less influential, yet innovative governments with the intention of causing policy diffusion to more influential governments was first touched upon in the EA forum post “Longtermist reasons to work for innovative governments”. Factors like high GDP per capita, long life expectancies and low income inequality can contribute to an increased chance of policy diffusion to other countries. It is especially common for less developed countries to adopt policies from countries with higher scores in these metrics.

Policy implementations (both successful and unsuccessful) from well developed and reputable countries can also provide valuable information that enables evidence-based policy making in other similar countries. This information can be useful to policy advocates when advocating for EA policies and when persuading policymakers in other countries. All these secondary effects from policy implementations in smaller countries could speed up the enactment of similar policies in larger countries. In this article we list some historical examples of policy diffusion, including the women’s suffrage movement, the abolishment of slavery and anti-smoking campaigns. A deeper dive into these examples and the policy diffusion process can be found in section 2.

The ideas discussed in this article could be relevant for several different actors, both globally as well as specific actors in the Nordics or similar geographies. These actors can be divided into three groups:

Policy advocates and policymakers globally, especially in large and influential countries such as the US or China. This group can benefit from collaborating more with peers in the Nordics or similar geographies.

Resource allocators globally, e.g. EA funders, career advisors and policy researchers. This group should allocate resources to support EA policy efforts in the Nordics or similar geographies. Career advisors should advise people with a good personal fit to work in policy in these countries.

Policy advocates and policymakers that are knowledgeable about the Nordics or similar geographies, especially people native to these countries. These people’s knowledge about their respective countries’ political system and culture is a big advantage for performing well in politics in their country of expertise.

Further implications for these three stakeholder groups are discussed in more detail in section 5.

To support the hypothesis that the EA community’s policy efforts are heavily weighted towards larger countries we have found some examples from the EA Funds site. For instance, one of the highest grants are sent to reform corporate policies on animal welfare like the Compassion in World Farming USA, Wild Animal Initiative (US), and The Humane League (UK). Another popular field of interest in terms of funding is AI-research. For example, the US and China are frequently recommended as targets for political reform, as shown in 80K hours’ article on China specialists, US AI policy and their congressional staffer career review.

In addition to the Nordics and the other smaller countries mentioned earlier, there is a group of countries which we refer to as mid-tier (including e.g. the UK, Russia, Germany, Brazil and Canada). These countries are somewhere between the small well-governed countries and the global great powers when it comes to the metrics mentioned above. These countries are bigger in scale with an increased potential for direct impact, but are likely less tractable for EA policy efforts because of the high scale and competition. Intergovernmental organizations (like the UN, NATO, ASEAN or WHO) and emerging geographies (like Nigeria, Tanzania or India) are other categories of policy making institutions that may present good opportunities for EA policy projects.

Despite our arguments in this article for increasing policy efforts in small countries, we still think that the EA community should have a primary focus on some of the world’s most populous and influential countries. Especially the United States, China, and the European Union. However, the large size of these countries could make direct EA policy efforts less tractable than in smaller countries. Spreading out EA policy efforts over a larger range of countries could have multiple benefits. This idea of taking a wider portfolio approach is discussed in more detail in section 3 of the article “Doing good together” by 80000hours. An overview of our arguments for focusing on a range of policy making institutions is presented in Figure 1.1.

Some aspects of large countries like the US and China make it harder to influence policy and therefore reduce the tractability of direct EA policy efforts in these countries. One of the reasons why EA policies fail is that they are being rejected by politicians for lacking political feasibility, as discussed in “Good policy ideas that won’t happen yet” from the Global Priorities Project. Many policies are rejected for being too financially costly for either governments or their voters. Other policies lack feasibility because the general public consider them strange or foreign, i.e. being excluded from the Overton window. This often leads to politicians rejecting policies to avoid the risk of losing political capital.

Another obstacle is lack of knowledge and scientific evidence to support new policies, which can reduce the chances of successful political reform. These are just a few examples of obstacles we might face in larger countries, and is not a comprehensive list of why policies fail. Throughout this article we discuss how policy projects in smaller countries can help get around some of these obstacles also in larger countries.

The Nordic countries’ small populations, high-trust societies and strong international reputations for good governance make them advantageous targets for EA policy efforts. Countries with smaller populations often have more members of parliament per capita than more populous countries, which could make it easier for policy advocates to access and convey policy ideas to policymakers.

Other cultural factors may also shape how easily EAs can gain influence. For instance, in smaller countries there is typically a smaller number of key policy makers and lobbyists, and they often know each other; knowing a handful of these policy makers or lobbyists may be sufficient to gain access to the entire local elite network. Also, Nordic countries also have a culture of valuing research and domain expertise, which is likely an advantage for aspiring EA policy advocates.

Smaller populations also means there are fewer people to influence to shift the Overton window, which leads to reduced resistance from citizens when trying to enact experimental EA policies. The high trust societies of the Nordics might further reduce resistance from citizens when implementing experimental policies. With less resistance and better access to policymakers, the tractability of EA policy advocacy could be significantly higher in the Nordics than in contrasting countries. Countries with international reputations for good governance also increase the chance of policy diffusion to other countries, especially to less developed countries. As a result, the Nordics can sooner export learnings from successful policies and facilitate policy diffusion to larger countries.

An example of the Nordics’ good reputation is Francis Fukuyuma phrase “getting to Denmark”′ in his 2011 book “The Origins of Political Order″, where he refers to Denmark as a prime example of a stable, peaceful, prosperous, inclusive and honest society. Furthermore, in historical terms, Norwegian politicians have also influenced global policy making through roles in international organizations. For instance, the Brundtland Commission introduced the term “sustainable development” and has through their work influenced many other countries to adopt more sustainable and long-term friendly policies.

Another advantage of the Nordics is their ideal test lab conditions for experimental policy implementations. The Nordics’ strong social safety nets, strong government capacities and low social complexities all contribute to improved test lab conditions. Strong social safety nets reduce the risk of negative outcomes from failed policy implementations, especially protecting lower social classes from adversities. The strong government capacities of the Nordics, i.e. a government’s ability to design and deliver policies increases the likelihood of successful policy implementations and reduces the risk of unexpected outcomes. Lastly, the Nordics’ low societal complexities could increase the accuracy of policy impact projections, which further reduces the risk of unexpected outcomes. The advantages of the Nordics as targets for EA policy efforts is discussed in more detail in section 3.

Norway has a history of funding several long-term friendly organizations and making a variety of proactive investments for climate change mitigation and increasing sustainability, we believe that it is a good target for longtermist policy efforts. The majority of these kinds of investments made by Norway are financed by Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM) and Research Council of Norway (RCN).

NBIM manages Norway’s Government Pension Fund, which is currently the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund. The fund is regulated by a rule known as “handlingsregelen”, which is intended to secure the wealth and well-being of future generations. Handlingsregelen states an annual withdrawal limit equal to 3% of the expected long-term real returns of the fund. The 3% withdrawn follows a variety of investment restrictions to prevent unethical and unsustainable investments.

Judging by Norway’s long-term friendly past and current government, long-term friendly policies are already well within Norway’s Overton window. This is likely a big boost to the tractability of longtermist EA policy efforts in Norway, as it removes a lot of the groundwork that is necessary in many other countries. RCN’s and NBIM’s history of longtermist investments is also a reason to believe that they are open to continuing making longtermist investments, which would further increase the tractability of longtermist EA policy efforts in Norway. A more comprehensive list of the Norwegian state’s longtermist investments can be found in section 4, along with a couple examples of longtermist policy opportunities that are unique to Norway.

There are also examples of longtermist projects in other Nordic countries, for example the Swedish Institute for Futures Studies (IFFS) in 1973. IFFS is still active today and functions as an independent research foundation conducting futures studies, they also work to inform the Swedish government and citizens about how to improve the lives of future generations.

2. Policy Transfer & policy exports

Improved policies in the Nordics can have an impact on the global future if successful policies are exported to more populous and influential countries. Based on this premise, we have performed a shallow literature review to uncover key findings in major policy changes. In addition to this, we provide some research data on policy diffusion, as well as some examples of current tools that let smaller countries have a larger impact than their size would suggest.

Our key findings:

Most policy changes evolve gradually, but some occur rapidly as a response to external shocks like public outcries and national spotlight as was the case in the suffragette movement following WW1.

By establishing international norms through pressuring and incentivizing countries to adopt desirable policies countries can make a substantial impact on policies globally.

The likelihood of policy adoption relies on adoption in neighbouring districts, but also on GDP, population density and type of industry.

Some specific political tools, like high-ranking nationals and funding think tanks, are used by several small nations today to allow them to “punch above their weight” in international contexts.

Policy transfer and policy exports will be referred to as ‘policy diffusion’, meaning the process of spreading policies either within the same level of governance (horizontal diffusion) like from state to state or town to town, or between different scales of governance (vertical diffusion) like national regulations to municipalities (Shipan & Volden, 2008). See Figure 2.1 for an overview of these two mechanisms. The slave trade is discussed to showcase how policies can develop within a specific country and how such policies can spread to other countries through for instance political pressure—i.e. horizontal diffusion since it spread from one government to another. We will discuss the suffragette movement and how it developed in the UK and US to illustrate the spread of policies within a single country, i.e. vertical diffusion as it spread from local regulations to national laws. Then we will describe the case study of Indonesian smoking laws to provide a modern example of policy diffusion with some data on the policy diffusion to give this section a stronger scientific foundation. Lastly, in section 2.3, we present a few examples of policy tools that are being used by small states today to gain international influence.

2.1 Theories on policy diffusion

There are a number of different theories on why policy diffusion occurs. These include learning, competition, coercion and mimicry. The most relevant and widespread mechanism is imitation diffusion. According to Marsh & Sharman (2008), mimicry typically happens when less developed countries adopt policies of other countries with higher GDP per capita, longer expected lifespan, lower inequality or otherwise better socio-economic outcomes. Governments can thus be motivated to mimic others from a desire for legitimacy. By mimicking other states, the government relies on the social advantages, domestically and foreign associated with the policies, not on the content and direct effect of the policies. (Marsh & Sharman, 2008) However, these four types of policy diffusion are not exclusive mechanisms working independently, rather they are all part of the dynamic process of policy change.

According to the punctuated equilibrium theory policy diffusion normally occurs gradually and incrementally through imitation and competition, however in certain instances this process is sped up. Rapid diffusion of policies can occur as a result of exogenous shocks like catastrophes that capture the public attention. For instance, in the US prior to the 1979 Three Mile Islands nuclear reactor meltdown, nuclear energy was described as “cheap and renewable”, following the accident it was depicted as a potential “health and environmental threat”. (Boushey, 2012) Events of public outcry can lead to policy diffusion curves depicted as R-curves, while the standard spreading pattern is S-shaped. See figure 2.2, where the Mandatory Motorcycle Helmet Laws rapidly spread between states in the US. Boushey (2012) argues that by exerting vertical pressure nationally—i.e. from government to the local level—policies can increase the probability of rapid policy diffusion.

2.2 Historical examples of policy diffusion

Case study 1: The suffragettes

In general terms, the suffragette movement advocated for women’s rights for a long time with limited success. Then a few countries started to allow women to vote and hold office, and this sparked policy change in other countries. This case study will focus on the origin of the movement in the UK and US, i.e. the vertical policy diffusion pattern.

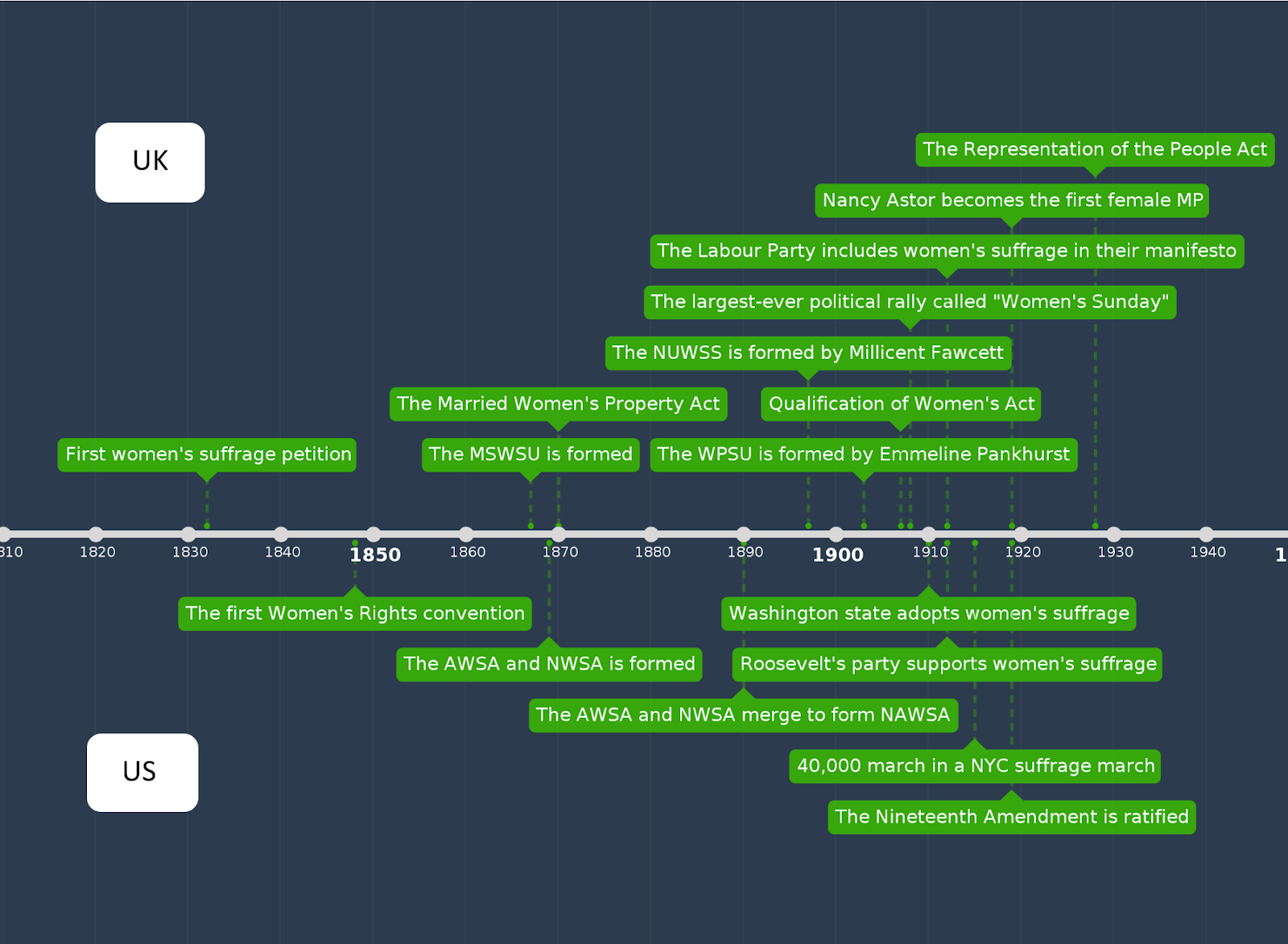

In the UK, the suffragette movement officially began in 1897, when Millicent Fawcett founded the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Society (NUWSS). (Bates, 2015) She argued for equal abilities between the sexes through peaceful protests, but she was unsuccessful in her first years. However, with the forming of Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) by Emmeline Pankhurst, the movement turned more violent to attract the attention of the lawmakers, as exemplified by their saying “Deeds not Words”. (Bates, 2015) In 1908, WSPU gathered 60,000 people to rush the Parliament, but the police held the building. (UK Parliament, 2021) By 1913, NUWSS had merged with 500 regional suffrage societies making the organization a highly influential alliance. (Myers, 2013) Finally in 1918 women were granted partial voting rights, and later in 1928, universal suffrage. See the women’s suffrage timeline above for details.

The suffragette movement struggled for a long time in the US, as exemplified by their shifting rationale, but in 1920 the movement had achieved its goal. In the beginning, some wealthy women wanted to push for universal suffrage by fighting the 15th amendment that granted voting rights to only black men. (History.com, 2009) Their attempt was futile, thus in the following Progressive Campaign in the 1890s, it was instead argued that women were different from men, and that it was their domestic virtues they possessed that made them eligible to vote. However, many middle-class white men were swayed by the argument that ensuring female suffrage would ensure a durable white supremacy. (History.com, 2009) Then, beginning in 1910 some states like Idaho and Utah began to extend suffrage to women and NAWSA president Carrie Chapman Catt promoted the “Winning Plan”. It consisted of blitz campaigning throughout the country with both the local and state level suffrage organizations. Following the end of the First World War, on August 18th in 1920, the 19th Amendment was ratified in the US and suffrage was granted to women as well.

From this case we can retain some key features that allowed this change: (1) the movement accumulated gradually in support and influence, (2) it maintained public attention to the issue, and (3) used rational arguments to convey their cause. Obviously other factors also played a role, like the racism in the US and the post-WWI changed image of women, but the main argument is oriented towards why the movement was successful in itself. Note also that in the UK, women were first granted partial voting rights in 1918, and then later in 1928, all women were allowed to vote over the age of 18. This might ensure a smoother transition and more durability in the following years.

Case study 2: The slave trade

The findings described below are inspired by Maurico’s post. We conclude that by convincing the public through local advocacy aided by economic incentives and nationalistic ideals, the UK ended its own slave trade and went on to enforce the policy change in other countries.

The abolition of the slave trade in Britain was a major policy change. The movement was led by Thomas Clarkson, who worked full-time to research the slave trade for the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. The change in policy began with local advocacy in London and Manchester by spreading information about the slave trade through pamphlets, books and newsletters. These works and other activist petitions increased public concern with the issue in 1788.

However, for a long time the slave trade lobbiest managed to defeat the abolitionists bills. It was not until the war with France and Napoleon’s attempt to strike back against a slave uprise in Saint-Domingue, that the british nationalistic ideals prevailed and the public finally called for a ban on the exportation of slaves. This bill got passed because the war with France made the slave trade economically risky and the public did not want to be associated with french morals. This bill allowed British merchants to seize ships that were exporting slaves, and so it became economically more beneficial to be opposed to the slave trade. In 1807, the UK officially abolished the slave trade and later went on to enforce the abolitionist policy on its colonies.

They promoted the policy internationally by funding abolitionist organizations, spreading abolitionist literature and directly pressuring other governments to abolish trading slaves. For instance, they forced the international Congress of Vienna to declare in 1815 that slavery is unjust and repugnant, and goes against the principles of humanity. This was then used again to pressure more countries to ban trading slaves. Although this global pressuring scheme was primarily motivated by morals, it was also economically well grounded as it ensured fewer competitors earning money on trading slaves. Thus they also worked to prevent other countries from achieving a monopoly on the trade.

By convincing the public, through local advocacy, economic incentives and nationalism, the UK ended its slave trade and went on to enforce the policy change in other countries. There is some uncertainty as to why the movement began in London, and Maurico speculates that the reason might be their dense networks, good organizing and industrialization.

In the international sphere the UK exerted significant influence and was able to use the momentum and public support to convince other countries to admit to certain principles of decency. They then used these principles to build on the agreement to force more countries to illegalize it. This shows how impactful policy change in a single country can be.

Case study 3: The anti-smoking campaigns

In recent years, most reforms are smaller in scope than slave trade and suffrage. However, modern reforms are still used to understand how policy diffusion works. One well-studied example are smoking laws. This case will focus on Septiono et al.’s (2019) policy diffusion study on Indonesia’s adoption of smoke-free policies (SFPs) from 2004 to 2015.

There are three reasons that Indonesia is an interesting case study. (1) Indonesia currently has the highest prevalence of regular male smokers (67% in 2013), in addition to (2) the highest prevalence of second-hand smoke for children under 15 (79% in 2016). Indonesia has also (3) not ratified the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) proposed by the World Health Organization. Thus the country lacks proper tobacco control on tobacco taxes, as well as general anti-smoking information. (Septiono et al., 2019) The authors of the article suggest that these conditions might be a result of a decentralized government. It is also interesting to note that Indonesia has an active tobacco industry and that this might incentivize the policy makers to enforce tobacco-friendly laws.

Septiono et al. (2019) found that in the 11 year period 143 out of the 510 distincts adopted smoke-free policies (SFPs). Herein, 15.1% adopted moderate policies and 12.9% strong SFPs. Furthermore, districts with high population density, high GDP and no tobacco production increased the probability of policy adoption. A multiple logistic regression showed that the probability of adoption in a given district increased by 2.02 if adjacent districts already had adopted SFPs (OR = 2.02; 95% CI: 1.26-3.23). Perhaps as expected, high tobacco production had a strong inverse relation to SFP adoption (OR = .036; 95% CI: 0.17-0.74).

Taken together, these findings suggest that there is a greater likelihood of policy adoption if neighbouring districts already have adopted said policies. Furthermore, other factors like GDP, population density, and the type of industry seems to influence policy adoption as well.

2.3 Current tools of policy exports used by small states

Despite somewhat limited economic and military influence, studies show that the governments of small states are purposely developing power despite their size on the few issues of high importance to them by actively influencing other nations’ governments. In the following we present a few examples.

Example 1: Small countries can address issues in international forums through high-ranking nationals or with the help of a beneficial reputation

Many small, democratic and rich countries are often disproportionately represented in international forums. In particular, many small, democratic countries have successfully placed several nationals in high-ranking positions in the UN system. Belgium, Sweden, Portugal and Norway have been particularly successful. For example, amongst the Secretaries-Generals of the UN, four out of nine have been from countries with less than 11 million habitants (Sweden, Norway, Austria and Portugal). Thorrallson explains that not only country characteristics like military and economic power provide influence; other factors seem to matter. He argues that states with significant competence in e.g. diplomacy, leadership or knowledge have an advantage in influencing the UN Security Council. The same goes for states that have a reputation of neutrality or being a “norm entrepreneur” in a particular policy field.

Example 2: Funding think tanks that influence on the world’s top decision makers

“The Center for Global Development” (CGD) is an example of a non-profit research organization that Washington lawmakers and government officials have long relied on for (more or less) independent policy analysis. Looking at their list of funding agreements active in 2021, we find political bodies of 6 countries listed, of which three have a population of less than 11 million. In 2014, the Norway Ministry of Foreign Affairs made an explicit agreement with CGD that in exchange for funding, CGD would push top officials at the White House, at the Treasury Department and in Congress to double spending on a United States foreign aid program.

3. Advantages of the Nordic countries in particular

The Nordic countries share certain traits that increase the likelihood of successful longtermist policy implementations which makes them good candidates for efforts to implement these policies. Some of these traits are easy access to policy makers, high levels of trust, a strong international reputation, and a non-hierarchical political system. In this section we will explore these traits and more, and attempt to explain why they make the Nordics well-suited for these efforts.

3.1 Easier access to current and future policy makers

Smaller countries, and nordic countries in particular, have easier access to policy makers

One can make an argument that it is easier to influence smaller countries’ governments than large countries’ due to easier access to policy makers. Figure 3.1 shows that the number of people per legislative seat increases as population size increases; there is a clear tendency of small countries having far fewer people per legislative seat. When each legislator has a smaller number of people who might seek their attention, it is reasonable to assume that each individual is more likely to reach through to a legislator who can address their view in the country’s legislative body.

Looking more closely at the small countries in figure 3.2, one can tell that Scandinavian countries (Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland) stand out even further when it comes to the number of people per legislator, also compared to countries of similar sizes.

People in the Nordics are aware that they have a high ability to influence the government

According to the OECD, Switzerland, Netherlands and Nordic countries display the highest perception of external political efficacy. External political efficacy is the perception of how much one person can have an effect on what the government does. This metric is influenced by people’s experiences when interacting with public institutions and to what degree institutions are perceived as responsive to the people’s needs.

Youth party members are accessible and likely to have a strong influence on politics in the future

Members of political youth parties are likely to become prevalent members of their parent parties. In Norway, every prime minister for the last 30 years has been a member of their youth party and over half of current cabinet ministers and parliamentary committee chairs have been members of their youth party. Leaders of youth parties are usually more available than leaders in their mother organization and might also be more open to influence. The potential to build connections/relationships with youth party members (and attempting to shape their political opinions over time) could be valuable.

When the elite is small, ideas can reach the majority of policymakers faster

Norway, Denmark, Finland and Iceland have no more than 200 seats in each of their national parliaments, which makes it much more likely that a policymaker with an idea can reach a majority of policymakers with little effort. Iceland is perhaps the most extreme example—with only 63 members of parliament, one can imagine that if one person has an idea, the necessary number of other people can quickly be persuaded so that the implementation of the policy may happen sooner.

3.2 Ideal conditions for testing policy implementation

High levels of trust increases the likelihood of sustained structural reform

The high levels of trust in governments in the nordics facilitates implementation and the sustainment of structural reform. According to the World Values Survey, the nordics score the highest in trust attitudes, with over 60% of respondents believing that people can generally be trusted. In the opposite extreme are countries such as Brazil and Colombia, where less than 10% of people believe this is the case. In low-trust societies such as these, citizens will prioritize immediate benefits and induce politicians to seek short-term gains. In high-trust societies, it is easier for governments to implement structural reform with long-term benefits. This is especially the case when these reforms require broader social and political consensus. In these climates, political reform can not only be properly implemented but also sustained long enough to bear their fruits.

The Nordic countries score highly on government capacity which increases the likelihood of successful policy implementation

In addition to high levels of trust, the Nordics also have strong government capacity. The capacity of government refers to the administration’s ability to design and deliver policies. When policies are implemented, the capacities of public institutions that deliver these policies matter a great deal for the success of that policy. If the government capacity is poor, as it often is in developing countries, policies are more likely to fail. This may happen because of corruption or power asymmetry, little will or persistance from public administrations, etc. This will also make it unclear whether the policy fails because of the nature of the policy itself or because of external conditions.

The Nordics are not affected by these issues. All Nordic countries score in the 90th percentile or above on most world governance indicators such as government effectiveness, political stability and control of corruption. The US and China range between the 20th and 90th percentile on these same metrics. This indicates that the success of policy implementations in the nordics is less likely to fail because of a lack of government capacity than in most other countries, including the US and China.

Low societal complexity and a flexible legal system lowers the risk of unforeseen consequences

The relatively lower complexity of small societies makes the risk of unforeseen failure of policy implementation smaller. One can argue that the amount of laws a country has is representative of its regulation and thereby the complexity of the society. According to Associate Professor Jon Christian Fløysvik Nordrum at the University of Oslo, American laws are 15 times as comprehensive as the Norwegian laws. Despite this, Norway is being ranked as #1 in the world in the Rule of Law Index, which might signify that fewer and/or more vague laws actually provide beneficial flexibility, which might improve the society’s ability to adapt to new policies.

3.3 Low risk of accidentally causing suffering or EA brand damage

There is low risk that policy failure will cause suffering in the Nordics

Any new policy implementation comes with risk, especially ambitious reform agendas. The outcome of the policy/reform is never certain, and failure to deliver the implementation properly could cause suffering to those the policy is intended for. Few examples illustrate this more clearly than different nations’ response to the coronavirus pandemic. The United States slow response to the virus outbreak, for example, along with the reduced funding for the CDC’s epidemic prevention activities, have very likely contributed to high death count in the United States.

These risks of ill-fated outcomes from failed policies are low in the Nordics. The Nordic nations generally have strong social safety nets and low income disparity, making the Nordic societies generally robust. Again, this is clearly illustrated by the coronavirus effect on different nations. The Nordic countries, being some of the nations that spend the most on the social contract, saw the lowest increase in government expenditure. Additionally, the nordics had the lowest increase in gross national debt, with Norway being the only OECD country to reduce gross national debt.

Because the Nordics are non-anglophone the risk of EA brand damage is low

Our hypothesis is that news stories from non-anglophone countries are somewhat shielded from information flow to the Anglosphere. This means that there is a lower risk of damage to the EA brand, should there be negative outcomes from policy implementation or reform agenda that was lobbied or endorsed by the EA movement. One analogous country that illustrates this mechanism is the clean-meat debate in France. The issue has been that the farming lobby portrays clean meat as robbing french farmers of their jobs and that this effort has strong funding from the silicon valley and is being organized by Effective Altruism. They for instance point out the Good Food Institute in France, as they have received substantial support from the silicon valley. This debate has however been mainly concentrated in France and has not transferred to other countries as of yet. As clearly stated earlier, this is anecdotal evidence, and so we encourage EA researchers to investigate this further if possible.

Note that we don’t believe that the information flow between the Nordics and the Anglosphere is entirely insulated. Therefore, an international movement of policy advocates (like the EA movement) can still leverage its active members on the ground in the Nordics and the Anglosphere to export successful policy projects from one geography to the other.

3.4 Strong international reputation increases likelihood of policy exports

The Nordics have a strong international reputation

The Nordic countries generally rank at the top or near the top in renowned international rankings, such as the UN’s Human Development Index, where all 5 Nordic countries rank among the top 11. Additionally, Nordic participation in international treaties and agreements such as NATO (with current secretary general Jens Stoltenberg, former prime minister of Norway), the EU/EEA and the OECD indicate a level of trust between Atlantic nations and the Nordics. In addition, the Nordic countries can be considered role models in terms of governance and social stability. The influence of this strong international reputation can be seen in american politics, with prominent members of the US Democratic party often referencing the Nordic model.

A strong international reputation facilitates policy exports

It is reasonable to believe that the strong international reputation of the Nordics will facilitate policy diffusion, should the policies have positive outcomes. This would be an example of policy diffusion by mimicry, which is discussed further in section 2.1. Governments may imitate their peers, especially those with a strong international reputation, simply because these high-status countries are considered to know best. This strong reputation may have facilitated the election of nordic officials to international positions such as general secretary of NATO Jens Stoltenberg or Gro Harlem Brundtland as chairperson of the now-called Brundtland Commision (formerly World Commision on Environment and Development). One might argue that this is also why the peace negotiations between Israel and PLO happened in Norway (Oslo accords).

3.5 Longtermist policy reforms are more likely to last in the Nordics

Longtermist policies have already been implemented in Norway

As of today policy implementations that are inherently longtermist have already had success, meaning they were implemented successfully and are well-liked, in the Nordics. One such example is the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Funds budgetary rule, or ‘handlingsregelen’. Handlingsregelen limits the expenditure of the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund for a single year, ensuring that the fund continues to grow for future generations. The budgetary limit was reduced from 4% annual spending to 3% in 2017, with the backing of all but one of the major national parties, which indicates some cross-party agreement on the prioritization of future generations. Another example from Norway is a government document known as ‘perspektivmeldingen’ (loosely translates to ‘the perspective message’) which outlines likely challenges Norway might face in the next 40 years, and possible solutions.

The Nordics are politically stable, with consensus-based politics

As mentioned in section 3.2, the nordics consistently rank above the 90th percentile in political stability indicators. Political stability indicates an increased likelihood that political reforms and policy implementations will last, as the risk of sudden shifts in government is relatively low. Additionally, the Nordic countries have a consensus-based policy making process. This has caused most major reforms in the Nordics to be backed across most major parties, and have made removal of political reform or implementations rare. One recent example of this is the climate settlement-reform (klimaforliket) which gathered support from 6 out of 7 parties. It is therefore likely that a longtermist reform in the Nordics could last for a long time. This would enable better analyses of the long-term impacts of the reform.

4. Examples of policies that Norway is fit to adopt

In addition to the advantages explained in section 3, Norwegian policies and institutions provide Norway with several advantages for implementing EA policies. Norway has a track record of investing in longtermist organizations, and investing proactively in e.g. electric vehicles. In addition, already existing institutions offer Norway in particular great opportunities for high impact policies. These institutions include the Norwegian Bank Investment Management (NBIM), and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Their potential for implementing EA policies will be explored in this section. In addition, Norway and other Nordic countries are digital frontrunners and can lead the research and development of artificial intelligence. The reason that we focus on Norway is because we have more in depth knowledge about Norway compared to other Nordic countries. However, other countries or regions similar to the Nordics may have equally important structures and opportunities.

4.1 Strong governmental funding for longtermist organizations

One reason why many longtermist organizations based in Norway have a substantial impact, is because they receive significant funding from the Norwegian state. For instance, Norway has a strong track record of investing in research within fields like climate change and pandemic preparedness. These organizations have proven to have a global impact and be leaders in their respective fields.

Here are some examples of longtermist organizations based in Norway:

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) is a partnership with public and private organizations that aims to develop vaccines to stop future pandemics. Together with Gavi and WHO, they are currently trying to accelerate the development and ensure a fair distribution of COVID-19 vaccines. CEPI has received 3.5 million dollars since 2014 from the Research Council of Norway.

Cicero is a globally leading climate change research institute, and aims to strengthen international climate cooperation. They have received approximately 90 million dollars in funding since 2004.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault offers safe long-term storage of seeds, and is considered one of the most important contributors in its field. Section 4.3 explores how the vault can have an even bigger impact by including genetically modified organisms. The Norwegian government established and fully funded the vault.

The Nobel Peace Prize is awarded to peace-promoting organizations or people by the Norwegian Nobel Committee. In addition to highlighting their effort and progress, the prize also highlights the importance of peace and long-term stability. Although this is a Norwegian ceremony, it is not funded by Norway. They are funded by the Nobel Foundation, which is located in Sweden.

The organizations mentioned above would presumably not have had such a massive impact without funding from the Norwegian state. Hence, Norway is a great place to start new longermist organizations focused on having a global reach and impact.

4.2 Proactive investments

Norway is actively using proactive investments to guide industries. Currently, most proactive investments are in fields related to climate change, in an effort to reduce domestic emissions of greenhouse gasses.

Examples of proactive investments:

Norway leads the world in electric vehicle (EV) adoption because of heavy proactive investments. The Norwegian Government wants all new passenger cars and city busses sold to be zero-emission by 2025. In 2020, 54% of all new vehicles sold in Norway were electric, and Norway became the first country in the world where EV sales surpassed fossil fuel vehicle sales. This is a result of proactive investments and strong governmental incentives to buy EVs. The incentives include: no purchase/import taxes, access to bus lanes and no annual road tax. A complete list of the Norwegian EV incentives can be found here.

The Norwegian Government also proactively invests in hydrogen ferries, and Norway is leading the development and technological progress in this field. The main barrier against hydrogen powered maritime transport is insufficient technological progress. Therefore, the Norwegian Government is funding research and pilot projects. The funding has resulted in e.g. the production of the world’s first hydrogen-powered ferry, which will transport both passengers and cars between Norway and Germany. There is also a Danish-Norwegian project that aims to build the world’s largest hydrogen ferry by 2027.

The Norwegian government proactively invests in actions that reduce greenhouse gas emissions from houses. Subsidies are provided by Enova, which is owned by the Ministry of Climate and Environment. Enova supports a wide range of actions including energy counseling and the installation of solar panels. A complete list, including price limits, can be found here (FYI: in Norwegian).

Norway’s openness towards proactive investments may be utilized further. Proactive investments related to climate change are probably easy to implement due to a long history of such investments. In addition, Norway can proactively invest in other areas such as pandemic preparedness.

Examples of potential future proactive investments:

Norway can increase proactive investments in fields related to climate change. As mentioned above, Norway already invests heavily in such fields in an effort to reduce domestic greenhouse gas emissions, and may further increase these investments. In addition, Norway has the opportunity to increase investments in clean energy sources. This will not reduce domestic emissions, as 98% of the electricity production in Norway comes from renewable sources, but it will support the global transition to renewable energy.

The development of meat substitutes is another potential investment area that could reduce domestic emissions, in addition to reducing the animal suffering in factory farms. It may be easier to implement proactive investments in this field since it includes reducing domestic emissions, which is generally regarded as an issue of high importance. Norway can e.g. invest in the research and development of cultured meat.

Pandemic preparedness is a non-climate change related field with enough attention and urgency to receive proactive investments. One example of how the Norwegian state has supported work in this space, is the funding of CEPI (see section 4.1) Norway could also invest in mRNA vaccine research, as this is a new and promising technology. mRNA vaccines have a high potency, can be developed rapidly, and have the potential for low-cost manufacturing.

4.3 Svalbard GMO vault

Norwegian law should allow the storage of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault to preserve GMOs and scientific progress in the case of catastrophe. With its isolated location, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault is safely storing seeds from all across the globe. Norwegian law prohibits the growth, development and importation of GMOs. Therefore, the “Doomsday” vault does not currently store any GMOs. In the case of a global catastrophe, GMOs may hence be partially or entirely lost. The loss of GMOs will also eliminate much of humanity’s scientific progress in this field, which would be an immense agricultural setback.

In addition, GMOs may be essential in the aftermath of a catastrophe because of their ability to withstand harsh conditions and to produce increased crop yields. Due to these advantages, GMOs may be crucial for the survival of humanity, and including GMOs in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault is therefore a high impact longtermist policy. This can be achieved either by nudging Norwegian policy-makers to be more GMO-friendly, or by making an exception for the vault.

4.4 NBIM ethical investments

The Norwegian Bank Investment Management (NBIM) is an impactful participant in the global investment market, and implementing ethical investments may therefore have significant consequences. The Norwegian Government Pension Fund is currently valued at 1.3 trillion dollars, and it is the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund. The current size of the fund is a result of the budgetary rule, which limits the use of oil revenues. This rule ensures that NBIM remains an impactful participant in the investment market.

Policies and statements made by NBIM get international news coverage by e.g. the Financial Times, which regularly writes articles about the fund. NBIM already has several ethical investment policies—e.g. restricting investments in coal companies, weapons manufacturer companies that are not in accordance with fundamental human rights (FYI: in Norwegian), as well as allowing unlisted investments in infrastructure for renewable energy. Such policies by the NBIM are powerful statements, and the global attention they receive often nudge the market to adopt similar policies. In the following months after the fund decided to cut investments in large coal companies, many other investors adopted similar or more radical restrictions.

By staying at the forefront regarding ethical investments, NBIM will presumably continue to create similar policy transfers. Such investments can include further divesting from fossil fuels, and investing in e.g. vaccine companies.

4.5 Leading AI research

Norway is among Europe’s digital frontrunners and may take a leading role in the collaboration, research and development of artificial intelligence. According to McKinsey, Norway and eight other European countries have the potential to drive the adoption of AI in Europe. This is because of “high levels of tertiary education, advanced digital infrastructure, populations that are amenable to new technologies, and strong corporate buy-in”.

In addition to the reasons mentioned above, Norway is a great qualifier to lead the research of AI due to high trust in the government. As mentioned in section 3.2, Norway and the other Nordic countries have high trust in their governments, which may make it easier to upscale AI-implementations to a national level.

5. Implications for stakeholders

So far, we have made the argument that there is potential for EA-aligned policy impact across a broad range of geographies, using the Nordics as a case study. In this section we cover the implications of this finding for a range of stakeholders. In short, we believe that there is a significant «home turf advantage» for some stakeholders, and that people aiming for careers as e.g. policy makers or -advocates should probably aim to do so in their own countries if there is room for more impact there. Other roles such as funders, career advisors or researchers can more easily cover a range of geographies in their work, and should therefore focus on supporting EA talent «wherever it is».

5.1 Stakeholders with domestic impact

Stakeholders with domestic impact include policymakers, policy advocates and policy developers. The policymakers decide which policies to adopt and which to discard through voting. Policy advocates aim to promote policies through lobbying. Lastly, the policy developers write up new suggestions for the policymakers to consider. However, it should be noted that these roles tend to overlap and are not necessarily as clear-cut as described here.

To succeed in these roles, the stakeholders should aim to build strong local networks and develop a good understanding of the culture. This means building lasting coalitions and exerting as much influence as possible within your political sphere. Careers like these therefore have a significant “home turf advantage”.

5.2 Stakeholders with global influence

The advantage of cross-continental stakeholders is that they can locate resources to the most promising figures/persons across national borders. These globally-oriented stakeholders include the funders, career advisors and researchers. The funders support initiatives and enable innovation across borders. Career advisors can help people around the globe with potential career pathways. Additionally, researchers can focus their efforts on either domestic or global topics, and the impact of the work can be substantial either way. These roles are generally viewed as supporting functions for those working “on the ground” since they supply talent, funding and insights.

To have impact through these roles, these stakeholders should enable impactful projects “on the ground”. As we have seen, it is possible to have impact even in geographies with smaller scale, as long as there is latent EA-aligned talent there to run the projects locally. To do this, people in these roles need to understand the geographies they support well enough to spot the best local opportunities for impact.

6. Summary

Currently, the EA funding and policy efforts are mainly concentrated around major political powerhouses like the US and UK. We recommend however, that more resources are allocated to a broader range of geographies, including emerging countries, multinational organizations, mid-tier and small, well-governed countries.

In this article, we especially consider the potential for impact in smaller countries with potential for exporting policies to other countries. This can be beneficial because smaller countries have certain advantages that enable stakeholders to exert more influence on policies. Geographies like this include: Singapore, New Zealand, Switzerland, Benelux, Canada and the Nordics.

We are most familiar with the Nordics, and think there is a strong case for EA-aligned policy projects here, because of factors like:

Easy access to current and future policy makers

High-trust society, strong government capacity and low societal complexity

Limited risk of EA brand damage or accidentally causing suffering

Strong international reputation

Norwegian policies are more durable

Finally, we consider the implications for some core groups of stakeholders in the policy space

On-the-ground stakeholders (like policymakers, policy advocates and policy developers) have a strong “home turf advantage” and should therefore strive to make domestic impact

Meanwhile, supporting stakeholders (like funders, researchers and career advisors) should aim to supply resources towards talent across geographies, not necessarily concentrated only in the geographies with the largest scale

I am a total novice in this area, but this seems like a really great post!

In addition to great content, it is well written, with crisp, clear points. It’s enjoyable to read.

I have a bunch of low to moderate quality comments below.

One motivation for writing this comment is that very high quality posts often don’t get comments for some reason. So please comment and criticize my thoughts!

The main point seems true!

I think the main point of scale and institutional advantages seems true (but I don’t know much about the topic).

Maybe another way of seeing this is that the 1% fallacy applies in reverse: in smaller countries you are much more able to effect change and the institutional lessons can then be transferred and scaled up in a second phase.

Critique: EA contributions are unclear?

I think a potential critique to your goal of attracting EA attention would be that the cause is not neglected.

To flesh this out, I think a variant of this critique would be:

Nordic planners and experts have both high human capital and are funded by state wealth (vastly larger than any existing granter). Combined with their cultural/institutional knowledge, this could be an overwhelmingly high bar for an outsider to enter into and make an impact.

Another way of looking at this, is that the premise overvalues EA—EA is a great movement. But it’s small, and it’s successes has been in neglected causes and meta-charity.

So a premortem might look like “Ok so a lot of EAs came in, but generally, their initial help/advice amounted to noise. Ultimately, the most helpful pattern was that EAs ended up adding to our talent pool for our institutions (alongside the normal stream of Nordic candidates). This doesn’t scale (since it adds people one-by-one) and doesn’t really benefit from specific EA ideas.

This point could be responded to with some “vision” or scenarios of how EAs would “win”. Maybe the EAF ballot initiative and Jan-Willem’s work on workshops would be good examples.

Longtermist policies versus good governance

You mention longtermism being implemented in Nordic countries.

Your examples included national saving withdrawals being codified at 3% per year, and programs giving explicit attention to time horizons of 40 years.

This looks a bit like “patient longtermism” (?)...but it mainly looks like “good governance” that does not require any attention to the astronomically large value of future generations.

Is it worth untangling this or is it reasonable to round off?

Thank you for your feedback! These are important points, and I’m glad you brought it up.

· EA contributions are unclear

This is a valid concern. However, we still believe EAs can add value to the policy making here, for two main reasons: 1) domain expertise on EA cause areas (that Nordic planners may lack even though they are generally competent) and 2) specialization in different parts of the policy making value chain (e.g. EAs can take roles as information suppliers providing a fact base that Nordic policy makers don’t have capacity to find themselves. The policy makers can then assess the information provided on its own merits, and hopefully reach the right conclusions (which may sometimes be different from what EAs would’ve done in their position).

· Longtermist policies versus good governance

Our main point here is not about whether Norway already has implemented the most important policies for future generations. Rather, we wanted to exemplify how longtermist initiatives already have a foothold in Norway and that this shows that longtermist values might be easier to translate into policies with enough EA policy efforts.

This makes a lot of sense. Thank you!

Agree with some of this, but:

The title should clarify that it’s “national scale” rather than scale generally that’s overrated.

US and China are probably more likely to copy their own respective states & provinces than copy the Nordics, right?

Being unusually homogenous, stable, and trusting might mean that some policies work in the Nordics, even if they don’t work elsewhere.

If we’re worried about whether govt pursues certain tech (like AI) safely over the coming 1-2 decades, then we should favour involvement in the executive over legislating, and the former can’t really transfer from the Nordics to the US. Diffusion may be rather slow.

Hi Ryan, thanks for your comment!

1) “The title should clarify that it’s “national scale” rather than scale generally that’s overrated.”

We did not use “national scale” because we cover policy making on both national-, subnational- and multinational scale. However, we agree that “scale” is very useful as a parameter in cause prioritization frameworks. You’re right that our claim is more narrow—only that it’s overrated in this specific setting.

2) “US and China are probably more likely to copy their own respective states & provinces than copy the Nordics, right?”

This is a valid point. For this reason, our logic can also be used to argue that EA should increase policy efforts in US states, or other sub-national policy entities. However, there are some policy domains that are mostly relevant on the national level (e.g. foreign policy), and there are examples where foreign examples work as better motivators (see e.g. this commercial which uses US patriotism to advocate for accelerated EV uptake in the US).

3) “Being unusually homogenous, stable, and trusting might mean that some policies work in the Nordics, even if they don’t work elsewhere.”

You’re right that some policies that work in the Nordics won’t work elsewhere! This is analogous to how some (small-scale) startups will pass a Series A round funding but not succeed at larger scale. Startups typically start with little funding and unlock increasing amounts of money. This way, if the startup fails, it fails in the cheapest possible way. Similarly, by testing new policies first in the most ideal governance environments and gradually scaling them to trickier environments with larger costs of failure, the policies that fail will do so in the least costly wa

4) “If we’re worried about whether govt pursues certain tech (like AI) safely over the coming 1-2 decades, then we should favour involvement in the executive over legislating, and the former can’t really transfer from the Nordics to the US. Diffusion may be rather slow.”

You’re right that if your main concern is linked to specific, urgent causes, you may prefer more direct routes to impact in the countries that matter most

This is such a great article! Thank you for writing it. Really interesting ideas.

Here’s a thing that came to mind when reading it.

You talk about policy diffusion seeming to be greater from high reputation countries. This seems quantifiable.

It seems both possible and powerful to build a map of the probability of policy diffusion from country A to country B for policy area X. (for all As, Bs and Xs). Simple example here (arrow size representing probability)

For example—this paper seems to have done something approximating this—see figure 1 in particular (although looks like it took a bunch of manual coding of parliamentary debate data).

The policy diffusion landscape has big implications for my own work (advising UK civil servants on where they can have impact in government), so really keen to talk to anyone working on this.

Hi Toby, thanks for the good insight and also relevant links—and apologies for the extremely delayed response! I thought I had already responded to this.

Agree that such a map would be valuable, though 1) I’m not sure if the data is rich enough to create a general map that works across all policy areas (due to substantial confounding factors throughout history), and 2) there may also be conceptual challenges (e.g., the strength of each arrow may differ by policy domain). Still, I think this is an important crux for the value of policy work in smaller countries, so agree that developing a better understanding would be valuable!

Thanks for the article, pretty interesting and really clearly written.

Minor aside, I found it interesting that (IIRC) this wrinkle of the history of abolition in Britian was not mention in William MacAskill’s What We Owe The Future, where he goes into some more detail on the history of abolition in UK.

Might be that the relevance of the conflict with France is rated as less important by other scholars?

Thank you Max, and good point! While we did try to use the state-of-the-art evidence in this piece I think I’ll defer to Will’s research team on that one—his take is probably closer to the current consensus among the relevant experts

An absolutely terrific post, thank you very much for writing this!

Thank you!