Adverse Selection In Minimizing Cost Per Life Saved

GiveWell, and the EA community at large, often emphasize the “cost of saving a life” as a key metric, $5,000 being the most commonly cited approximation. At first glance, GiveWell might seem to be in the business of finding the cheapest lives that can be saved, and then saving them. More precisely, GiveWell is in the business of finding the cheapest DALY it can buy. But implicit in that is the assumption that all DALYs are equal, or that disability or health effects are the only factors that we need to adjust for while assessing the value of a life year.. However, If DALYs vary significantly in quality (as I’ll argue and GiveWell acknowledges we have substantial evidence for), then simply minimizing the cost of buying a DALY risks adverse selection.

It’s indisputable that each dollar goes much further in the poorest parts of the world. But it goes further towards saving lives in one the poorest parts of the world, often countries with terrible political institutions, fewer individual freedoms and oppressive social norms. More importantly, these conditions are not exogenous to the cost of saving a life. They are precisely what drive that cost down.

Most EAs won’t need convincing of the fact that the average life in New Zealand is much, much better than the average life in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In fact, those of us who donate to GiveDirectly do so precisely because this is the case. Extreme poverty and the suffering it entails is worth alleviating, wherever it can be found. But acknowledging this contradicts the notion that while saving lives, philanthropists are suddenly in no position to make judgements on how anything but physical disability affects the value/quality of life.

To be clear, GiveWell won’t be shocked by anything I’ve said so far. They’ve commissioned work and published reports on this. But as you might expect, these quality of life adjustments wouldnt feature in GiveWell’s calculations anyway, since the pitch to donors is about the price paid for a life, or a DALY. But the idea that life is worse in poorer countries significantly understates the problem - that the project of minimizing the cost of lives saved while making no adjustments for the quality of lives said will systematically bias you towards saving the lives least worth living.

In advanced economies, prosperity is downstream of institutions that preserve the rule of law, guarantee basic individual freedoms, prevent the political class from raiding the country, etc. Except for the Gulf Monarchies, there are no countries that have delivered prosperity for their citizens who don’t at least do this. This doesn’t need to take the form of liberal democracy; countries like China and Singapore are more authoritarian but the political institutions are largely non-corrupt, preserve the will of the people, and enable the creation of wealth and development of human capital. One can’t say this about the countries in sub Saharan Africa.

High rates of preventable death and disease in these countries are symptoms of institutional dysfunction that touches every facet of life. The reason it’s so cheap to save a life in these countries is also because of low hanging fruit that political institutions in these countries somehow managed to stand in the way of. And one has to consider all the ways in which this bad equilibrium touches the ability to live a good life.

More controversially, these political institutions aren’t just levitating above local culture and customs. They interact and shape each other. The oppressive conditions that women (50% of the population) and other sexual minorities face in these countries isn’t a detail that we can gloss over. If you are both a liberal and a consequentialist, you should probably believe and act as if individual liberties and freedom from oppression actually cash out in a significantly better life.

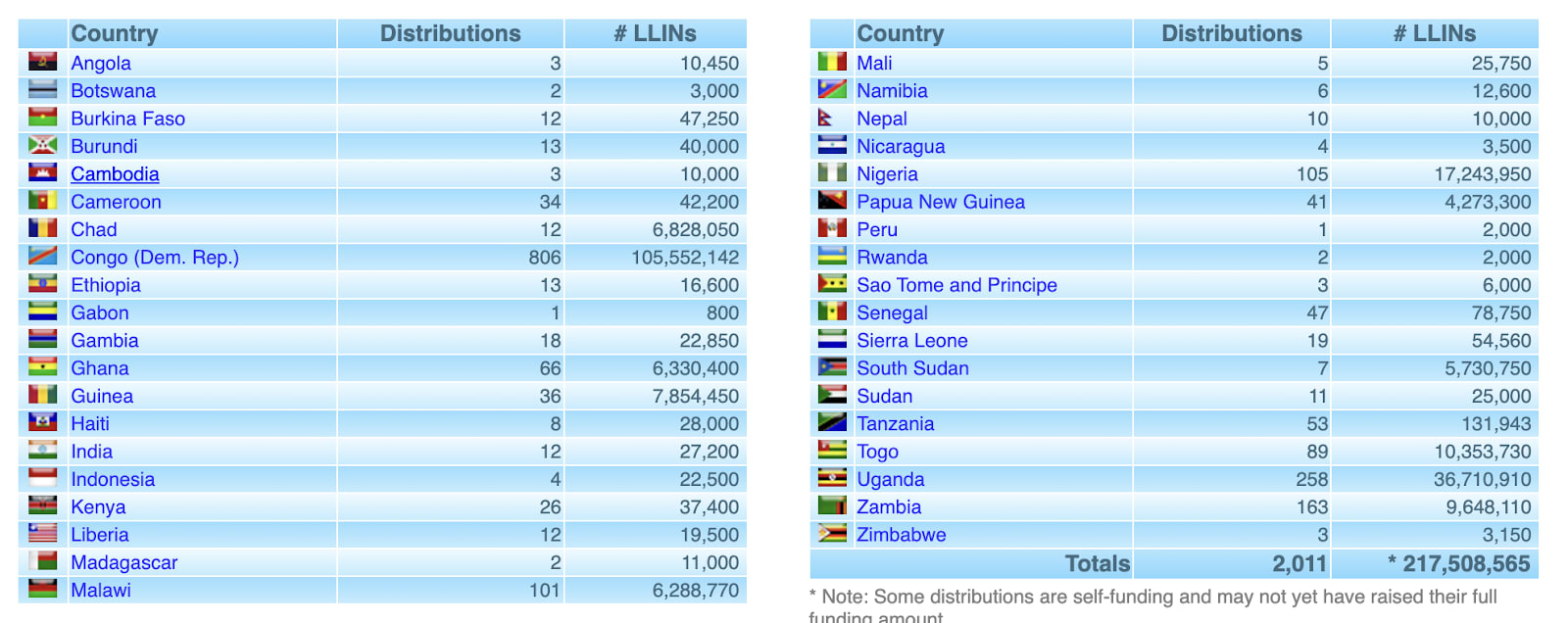

You can get a better sense of this by looking at the list of countries AMF buys most of its DALYs in:

Democratic Republic of Congo is the country that tops the list, with over 100 million bednets. These excerpts from the World Bank country profile may not come as a surprise to most of you:

“DRC ranks 164 out of 174 countries on the 2020 Human Capital Index, reflecting decades of conflict and fragility, and constraining development..”

“Congolese women face significant barriers to economic opportunities and empowerment, including high rates of gender-based violence (GBV) and discrimination. Half of women report having experienced physical violence, and almost a third have experienced sexual violence, most commonly at the hands of an intimate partner...”

“DRC has one of the highest stunting rates in SSA (42% of children under age five), and malnutrition is the underlying cause of almost half of the deaths of children under the age of five. Unlike other African countries, the prevalence of stunting in the DRC has not decreased over the past 20 years. Due to the very high fertility rate, the number of stunted children has increased by 1.5 million.”

Quantifying quality of life

Valuing a life (or life year) has three components:

Hedonic value of the life itself

Psychological trauma/grief averted by family members (when you save a life)

Externalities (how the person’s life affects others)

Whether you save a life in Congo, Sri Lanka or Australia, I can’t think of strong reasons for why #2 would vary all that much.

We should expect #1 and #3 to be some function of per capita GDP, human capital development, individual freedoms etc. As Give Well reports “People in poor countries report that they are on average less satisfied with their lives than people in rich countries. The average resident of a low-income country rated their satisfaction as 4.3 using a subjective 1-10 scale, while the average was 6.7 among residents of G8 countries”. But this doesn’t help us quantify the differential value of lives.

You could ask reasonably well off people in the developed world at what level of fixed yearly income in their own country they’d be indifferent to moving to sub-Saharan Africa with all their money. But we’d need to deal with the challenge of disentangling how much of that effect is simply an attachment to one’s own relationships, sentimentality etc. ANother way into this would be to study demand for immigration from the poorest countries. For example, “In 1990, an estimated 300,000 Congolese migrants and refugees resided in one of the nine neighboring countries. By 2000, their number had more than doubled by 2000 (to approximately 700,000), and by mid-2015, had risen to more than 1 million in the neighboring countries.”. The vast majority of migration out of Congo took place after the official end of the war, which tells us something about the baseline conditions, not just threat of imminent violence. But we should note that economic migration, both legal and illegal, is not affordable and accessible to the people who are worst off within the poorest of countries. And trying to find the cheapest lives to save will systematically bias you towards lives which are worse than any estimate gathered from immigration data would suggest.

Present vs future quality of life

Notwithstanding the methodology used, the adjustments here need to incorporate two factors—the present quality of life and expected future quality of life, especially since most life saving interventions are targeted at children.

(1) Present quality of life is a function of per capita income, income inequality and measures of human development and freedoms. It’s absurd to end up with a framework that believes a life for a woman in Saudi Arabia is just as good as life for a woman in some other country with similarly high per capita income.

(2) The expected future quality of life is some function of growth prospects, institutional quality and trends in institutional quality.

What does this point to?

At first glance, this favors saving lives in countries that are still poor or have very poor parts but much better state capacity and institutional quality and thus better prospects.(eg. Bangaladesh, India vs DRC) In these instances, DALYs may still be available at a low price but those future DALYs are much higher quality DALYs than the ones you’d be buying in countries that seem to struggle with bad political equilibria.

More generally of course, based on the magnitude of adjustments, it could just move one away from the project of saving lives in the developing world altogether, perhaps towards more of alleviating acute suffering or interventions that would have an impact on human capital (like lead removal) and institutional quality in the long run.

Conclusion

Here’s how GiveWell concludes its analysis on standard of living in poor countries :

“On one hand, people in the developing world have a tangibly lower quality of life. On the other hand, a life saved probably means many more years of functional life. We feel strongly that it’s worth addressing a major problem (such as tuberculosis or immunizations) even if other problems remain unaddressed.”

While I agree with that general sentiment, we still have to contend with the fact that these other problems remained unaddressed are not independent of how valuable it is to solve specific problems within these countries. The conclusion may or may not look vastly different from the status quo but the prospect of adverse selection means that we shouldn’t be too surprised if the shift is significant.

My impression is that GiveWell is on principle explicitly against treating different lives as having different values, even when the mechanism is as simple as different lives having different expected lengths (e.g. valuing saving someone from malaria less if you think they will have a lower life expectancy as a result of their illness).

From a straightforward, surface-level utilitarian perspective, this does seem like it would be a mistake. But I think there are good rule-utilitarian, systems-change, or co-operation-based reasons to want to take this stance.

Treating different lives as worth different amounts violates many people’s fairness and justice intuitions, which is both relevant from a moral-trade perspective (it’s a good co-operative principle to avoid doing things that other people really don’t want you to do) and a moral-uncertainty perspective (maybe they are correct to not want you to do those things!)

It’s also pretty uncomfortable that part of the reason that these people live in such difficult conditions is that previous generations have neglected to help them: a policy that discounts them on this basis will tend to reinforce existing problems.

As you say, the fact that they are the cheapest lives to save and the fact that they have poor state capacity are causally related, but they’re probably causally related the other way too, in the sense that it’s hard to demand or build good state capacity when you’re sick or barely feeding yourself. I hope that as material conditions improve in (say) the DRC, so too will political conditions; I’m no historian but that seems to have been the trend in much of the rest of the world.

(I have more to say but I have 2% phone battery so maybe I’ll make another comment later)

Yep. A significant portion of the relevant health economics literature Givewell researchers will be familiar with uses measures which do treat lives as non-equal, typically the “value of a statistical life” which represents how much society is willing to pay to save that life which is broadly proportional to GDP per capita. The rationale is basically that survivors in richer societies are capable of generating enough wealth to cover the costs of their treatment, but if you’re valuing lives from an altruistic perspective then you really, really don’t want to weight it based on future ability to pay...

That “value of a statistical life” obviously factors in differences in opportunities and values positive externalities generated from surviving, but vastly overweights differences in actual quality of life—and even on value-of-a-statistical-life grounds malaria nets and vitamin supplementation in Sub Saharan Africa is generally still seen as cost effective.[1] From a pure hedonic utilitarian perspective you might want to use some sort of subjective wellbeing factor instead. Multiply that by the expected future life of the person saved and you get the WELLBY as an alternative metric [2]

But the difference in average self-reported subjective wellbeing on a linear scale is… really not very big compared with the differences in costs between countries, and probably isn’t going to change their recommendations very much. Taking the example of the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Congoese people polled do indeed value their happiness at lower than many other countries on the World Happiness Poll’s nominally linear scale at only 3.3 out of 10. But India and Bangladesh, highlighted in the post as countries which don’t have ongoing conflict and plausibly have better economic opportunities, score only 4.1 and 3.8 respectively so factoring in the weightings of subjective wellbeing—if you believe them to be accurate—would change very little. (The main reason why comparatively few nets are dispensed in India and Bangladesh is that the local malaria variety is a lot less prevalent and a lot less lethal. The life expectancy difference to Congo shrinks if you factor out malaria too...). And if children survive infancy, their lives are typically lived over spans of 60-70 years. It’s unlikely the global distribution of happiness will be identical 30 years from now, and entirely possible that the countries with the lowest happiness will see the biggest improvement

So whilst GiveWell may have made the judgement to weight lives equally on ideological grounds, the actual data you’d need to create a robust argument for doing things differently tends to not be there or broadly inclined to what they’re already doing...

people in richer countries not only face proportionally higher healthcare costs in general, but also diminishing returns since the treatments they’re at risk of missing out on tend to be expensive and complex surgery and new experimental drugs, rather than vitamins and nets...

using national life expectancy figures which are significantly affected by malaria prevalence in infants as weights which discourage supplying malaria nets is questionable, but in theory life expectancy measures could be adjusted to factor malaria out....

Appreciate the response. Descriptively, I’m sure you’re right about the rationale behind these decisions. I think failing to factor in even the most obvious drivers of quality of lives might be politically more comfortable but has important implications, perhaps even for these specific populations. For example, making adjustments might justify:

1. Moving dollars towards interventions aimed at human capital development (lead removal, (perhaps) deworming).

2.Saving more lives in countries that have regions that are quite poor but have better future prospects.

I’m also skeptical of the idea that generally improving public health on the margin will contribute in any meaningful way to improving institutional quality. I’m not arguing as some libertarians do that doing this hampers the incentive to provide public services. But on the other hand, it’s also far from likely that improving public health will improve instituions in the long term. I agree the causation might run both ways but probably much stronger in one direction. (especially since there are all too many examples of places with much better public health but awful institutional quality (Venezuela, Iraq etc come to mind)

Fascinating, I can’t believe I’ve never heard this argument before.

The difference in subjective well-being is not as high as we might intuitively think.

(anecdotally: my grandparents were born in poverty and they say they had happy childhoods)

Doing a naive calculation: 6.7 / 4.3 = 1.56 (+56%).

The difference in the cost of saving a live between a rich and a poor country is 10x-1000x.

It would probably be good to take this into account, but I don’t think it would change the outcomes that much.

“Doing a naive calculation: 6.7 / 4.3 = 1.56 (+56%).”

Perhaps I rate things differently to most survey respondents, but for me anything less than 5⁄10 is net suffering and not worth living for its own sake.

Consider the difference between “saving” 10 people who will live 1⁄10 lives (maybe, people being tortured in a north Korean jail) and one person who will love a 10⁄10 life

Very good point. Yeah, it seems like a 1⁄10 life has to be net negative. But a 4⁄10 life I’m not sure it’s net negative.

I think you raise an important point: people legitimately have different opinions on what the scale should mean, and there might also be cultural factors that skew how people perceive they should respond on aggregate. If there is such a thing as a true hedonic scale for how people actually feel about their life that can be compared from person to person, survey data isn’t an ideal proxy for it.

But I don’t think the average person responding assumes the valence symmetry that you probably assume. Most people do want to go on living and so it’s not unreasonable to assume that the bottom half of the scale which goes all the way up to the “best possible life” isn’t supposed to represent different degrees of unbearable torture. I imagine most of the large fraction of the world’s population who awarded themselves a 4⁄10 on that scale would be utterly horrified by the idea that this might imply their life wasn’t worth living.

Executive summary: Minimizing cost per life saved in global health philanthropy risks adverse selection by systematically biasing towards saving lives in countries with worse overall quality of life, necessitating adjustments for factors beyond just disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

Key points:

Simply minimizing cost per DALY saved ignores significant variations in quality of life between countries.

Cheaper life-saving interventions are often available in countries with worse political institutions, fewer freedoms, and lower prospects.

Factors like institutional quality, individual liberties, and future growth prospects should be considered when valuing lives saved.

Quantifying quality of life differences is challenging but necessary, potentially using metrics like subjective well-being or migration patterns.

This analysis may favor interventions in poor but improving countries over those stuck in bad equilibria.

Depending on adjustment magnitudes, this could shift focus away from life-saving in developing countries towards other interventions.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.