Road Safety: The Silent Epidemic Impacting Youth

KEY FACTS

Road crashes are the #1 cause of death for young people aged 5-29, who account for 52% of the global population.

Road crashes are the #8 cause of death for the population overall, causing at least 1.35 million deaths and 50 million injuries per year.

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) account for 93% of worldwide road crash fatalities, despite having 60% of the world’s registered vehicles. Death rates are three times higher in LMICs than in high-income countries, and LMICs are home to 90% of the world’s population under 30 years old.

While 500 children die on the roads each day, this crisis not only affects families and sociocultural welfare, but also the workforce of developing nations. LMICs miss out on 3-6% GDP growth per year due to the healthcare burden, lost labor, and lost welfare caused by road crashes, summing to a global economy loss of at least $500 billion USD per year keeping as many as 70 million people in poverty worldwide.

Road fatalities and injuries can be effectively curbed in a cost-effective manner through targeted initiatives such as: child seatbelts & restraints, helmet use, speed reduction, drink driving prevention, “forgiving” road infrastructure, school zones, global advocacy, and public awareness campaigns.

DISCLAIMER OF BIAS

This is a rapid, non-exhaustive investigation of this cause area. This paper is written by Molly Stoneman and Jimmy Tang, two people passionate about road safety and working for AIP Foundation – a road safety NGO in Southeast Asia – who have studied road safety as an underfunded cause area in their professional work but are not academic experts.

Road safety is an extremely dimensional and interconnected issue with cross-cutting studies in urban planning, civil engineering, mechanical engineering, environmental sustainability, public health, education access, poverty, gender studies, human rights, and more fields. There may be relevant evidence that we have missed or assumptions we have overlooked, especially pertinent to how road safety issues manifest differently by country (and even by city within countries). This paper aims to provide a high-level look at the global problem for young people 5-29 years old.

WHAT IS THE PROBLEM?

What is the #1 killer of people aged 5-29? The answer is not malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, or infectious diseases – but road crashes. Road traffic crashes now represent the eighth leading cause of death globally, claiming more than 1.35 million lives each year and causing up to 50 million injuries, and is on track to move up in the list to the seventh leading killer by 2030.

Around the world, someone dies from a road accident every 25 seconds. This is equivalent to 5.2 jumbo jet planes crashing down per day – which would surely make global news. Yet the head of the United Nations Road Safety Fund has called road deaths and injuries a “silent epidemic,” which is needlessly ignored by many who think that crashes are accidental, unavoidable, and each individual’s responsibility to prevent.

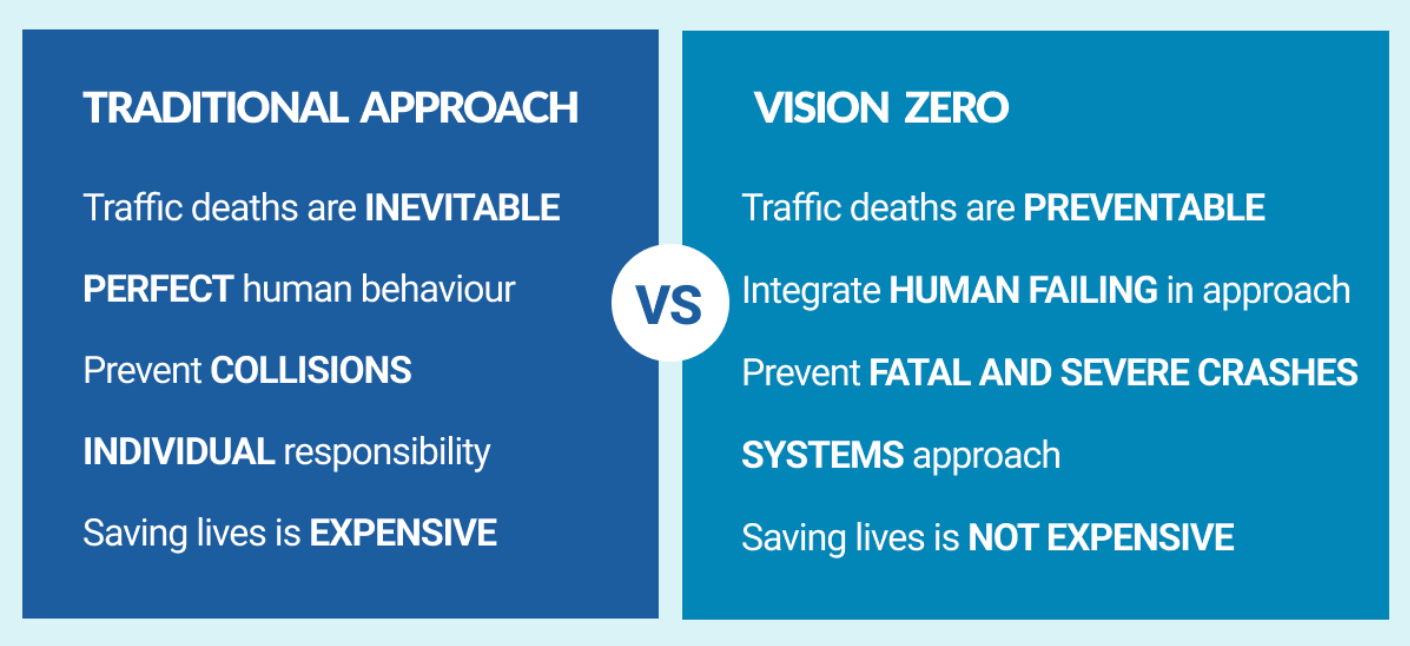

Crashes are not inevitable, but preventable.

Crashes are not a failure by an individual, but a failure by systems of transport.

Of course, not all roads are created equal. On a global level, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have seen rapid motorization that far outpaces the rate of road infrastructure development. There continues to be a strong association between the risk of road traffic deaths and the income level of a country. This is supported by the fact that LMICs account for 93% of worldwide road crash fatalities, despite having 60% of the world’s registered vehicles. Death rates are three times higher in LMICs than in high-income countries. That’s right, road safety is a social justice issue, with deep links to the global income gap.

This income gap is made stickier by road crashes’ negative impact to GDP growth. The greatest share of mortality and long-term disability from road traffic crashes happen amongst the working-age population (between 15 and 64 years old). The WHO estimates that LMICs suffer a 3-6% GDP loss per year due to road deaths and injuries (from healthcare costs, lost labor, infrastructure damage, and welfare loss to families) while the World Bank estimates a 7-22% GDP loss over a 24-year period, depending on a country’s income level. Meanwhile, on average, a 10% reduction in road traffic deaths raises per capita real GDP by 3.6% over a 24-year horizon.

Consider who is most at risk on any given road: at least 54% of global road victims are pedestrians, bicyclists, and motorcyclists.[1] Obviously, they lack external protection in case of a crash, but also tend to be lower income (those who cannot afford a car) and are more likely to be young (who cannot afford a car, are not yet legally eligible to drive, or are a passenger). The WHO notes that ‘vulnerable’ road users (youth, motorcyclists, pedestrians, bicyclists) are routinely exposed to risks on the world’s roads, largely due to gaps in road traffic system and infrastructure design. For instance, many countries still lack separate lanes for cyclists, rarely provide pedestrians with safe crossing areas, and have not made enough progress to reduce and enforce lower motor vehicle speeds.

For all this doom-and-gloom, making transport systems safer is feasible and is not rocket science. We can effectively improve the road safety crisis to better protect vulnerable road users in LMICs through coordinated support from multisectoral actors, localized interventions, and a paradigm shift around the right to a safe journey.

THE YOUTH ROAD CRISIS IS IMPORTANT

Road crashes disproportionally affect young people, as the leading killer of people aged 5-29 years worldwide. An estimated 500 children will die on the roads every day, far outpacing malnutrition (140 lives/day) and malaria (80 lives/day). Given that developing nations are home to 90% of the global population under age 30, we need to focus on the youth road crisis with priority for low- and middle-income countries. For example, the most vulnerable (i.e., pedestrians, bicyclists, motorcyclists) road users represent 59% of all road crash deaths in Southeast Asia and 53% in Africa, whereas they represent 43% of all deaths in Europe and 48% in the Americas. Furthermore, vulnerable people have to bear more of the adverse impacts of road crashes, such as costs of prolonged medical care or loss of income, which can push the impacted families into a cycle of permanent poverty.

Road traffic crashes are undermining the world economy and keeping millions in poverty. The global economy loses at least $500 billion USD per year as a result of road traffic collisions. This keeps as many as 70 million people in poverty and increases costs for businesses worldwide.

For every child that dies in a road crash, another four are permanently disabled and ten more are seriously injured. Road traffic injuries result in more than one million children each year having their education abruptly ended or severely disrupted, which restricts their right to education enshrined in Article 28 of the UN Convention on the Rights of a Child, posing enormous economic and social implications for future generations.

The combination of unsafe road conditions near schools, the special vulnerability of children, and the elevated risk tolerance of young drivers expose youth to daily risk of road injury/death. Due to their small stature, it can be difficult for children to see surrounding traffic and for drivers and others to see them. In addition, if they are involved in a road traffic crash, their relatively soft heads make them more vulnerable to serious head injury than adults.

With a safe journey to school, kids’ access to education increases. A safe journey also saves the country costs in medical care and lost labor output. With improved sidewalks, families are encouraged to walk or bike, which contributes to a healthy lifestyle of exercise and decreases carbon emissions.

THE YOUTH ROAD CRISIS IS NEGLECTED

In case you missed it: Road crash injuries are the single leading cause of death for children and young adults aged 5-29 years. This should be splashed on newspaper front pages constantly. But this is likely the first you’re hearing about the road safety movement. Why is that?

Society’s default attitude to hearing about a road crash is that it was an unavoidable accident probably stemming from the driver making a human error. Slowly, the road safety movement is pushing for a paradigm shift to reframe road deaths and injuries, centering on the fact that crashes are preventable. But like all societal shifts, progress is slow, and in this case made complicated by the fact that there is not one clear fix-all solution but many smaller, interconnected steps taken by countless multisector actors which will move the needle. These can be summarized by two dominating philosophies for transport safety improvement: Vision Zero and the Safe Systems Approach.

Road safety advocates were excited in 2004 when the United Nations and World Health Organization United Nations Road Safety Collaboration (UNRSC), a membership body of over 70 agencies, governments, foundations and academic institutes, road safety nongovernmental organizations and private companies. The UNRSC’s main functions are focused on awareness campaigns (like the annual UN Road Safety Week and establishing World Remembrance Day for Road Traffic Victims on the third Sunday in November), conducting academic research on the status of road safety, and publishing technical guidance for best practices in interventions, policies, data systems, and management systems. Notably, UNRSC is not a funding body.

The UNRSC established the Decade of Action for Road Safety from 2011-2020, with the aim of stabilizing and reducing the global rate of road fatalities over ten years. In short, the results were mixed.[2] Predictably, high-income regions tended to see a decrease in road safety fatalities/injuries while low-income regions tended to see an increase. The Decade of Action is by no means a failure, since it mobilized massive coordination and action worldwide, but following the close of the decade, we are still far from achieving our global goals. The UNRSC has since declared a Second Decade of Action for Road Safety from 2021-2030 with the ambitious goal to prevent 50% of road deaths and injuries by 2030.

In 2015, the issue of road safety was further elevated in the international development field through the integration of two Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets, Target 3.6 and Target 11.2. The inclusion of road safety in the Sustainable Development Goals was taken as a positive sign, and has been a motivating force for road safety advocates to drive attention and funding to this field.

There are many multilateral organizations, government coalitions, research institutes, development aid agencies, and on-the-ground NGOs implementing road safety projects. The big gap is in funding. (See section “Who is already working on it?” for details.) The major players for road safety funding are the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA, plus their philanthropic wing FIA Foundation), Bloomberg Philanthropies, Bernard Van Leer Foundation, Fondation Botnar, and The UPS Foundation. While appreciative of these funders, we believe that that the #1 killer of young people is a far outsized problem than this brief list can solve.

THE YOUTH ROAD CRISIS IS TRACTABLE

We can address the road crisis for young people because we have evidence for its root causes, for cost-effective solutions, and for resulting economic impact.

We have the evidence showing which behaviors make young people riskier drivers. For example, in younger drivers a combination of their undeveloped driving skills and poor judgment increases their tendency to engage in higher-risk behaviors including: speeding, following other vehicles too closely, rapid lane changes, and distracted or drunk driving. We also know that men under the age of 25 years are nearly 3 times more likely to die from a road crash than young women; several contributing factors include higher rates of alcohol consumption, concepts of masculinity in certain societies which promote a higher likelihood to engage in risky driving or risky pedestrian behavior, and higher rates of driving among men in countries where women’s mobility is restricted.

We know the most cost-effective solutions to target: speed reduction, helmet use, “forgiving” infrastructure, and public awareness campaigns. We note that these are in addition to less cost-effective solutions, such as: government advocacy and lobbying, drink driving campaigns, distracted driving campaigns, police enforcement campaigns and staffing, vehicle safety regulations for manufacturing, and comprehensive post-crash care services (including emergency transport and hospital care).

We know that road fatalities and injuries (RFI) hurt countries’ economies, with a disproportionate impact on developing nations’ economies. The 5-29 age group is deeply important to workforce contributions and sustainable development. RFI affects the economy through the loss of effective labor supply due to mortality and morbidity. Higher mortality rates reduce the population, and therefore the number of working-age individuals, while non-fatal injuries reduce productivity and increase absenteeism. Clearly, healthier individuals could reasonably be expected to: produce more per hour worked; make more efficient use of technology, machinery, and equipment; and be more flexible and adaptable to changes (e.g., changes in job tasks and the organization of labor). All of these reduce job turnover and associated costs.

Road fatalities and injuries in LMICs have been estimated to cause economic losses of up to 6 percent of GDP. Employing a fuller economic model, a related World Bank analysis suggests that RFI has a negative macroeconomic impact in low-and middle-income countries, with losses to GDP of 7% to 22% over a 24-year period. When analyzing case studies for 5 LMICs, WB found that from 2014-2038, halving deaths and injuries due to road traffic could potentially add 22% to GDP per capita in Thailand, 15% in China, 14% in India, 7% in the Philippines and 7% in Tanzania.

Meanwhile welfare gains—a more generally accepted concept of impact—are even higher. The World Bank study has quantified these gains for the five countries using a range of income and risk reduction scenarios. Measured in 2005 US dollars, the welfare gains range between $5,000 to $80,000 in Tanzania, and between $850,000 to $1.8 million in Thailand.[3]

WHY BELIEVE THESE ESTIMATED HARMS?

We believe this data is reliable and verifiable. Most of the data from this report comes from the World Health Organization, World Bank, and United Nations Road Safety Collaboration. We do not believe any public or private actors have incentive to artificially inflate the number of deaths and injuries caused by road crashes.

If anything, it is reasonable to believe police and governments have incentive to under report road crash deaths and fatalities. After a crash—especially in the case of LMICs—police may be prone to bribes not to file an official report which leads to underreported numbers. (Look no further than a famous case in Thailand where a wealthy energy drink heir drove drunk and killed a policeman, but still has not been prosecuted 10 years later.) Police are not always trained on properly reporting about the nature of the crash, meaning the cause (speeding, distracted driving, etc.) data may be skewed.

Governments—specifically, Ministries of Transport—are the main data sources to the WHO and World Bank. They have incentive to underreport crash numbers in order to show that they are making “progress” year over year to powerful multilateral organizations, who are often providing aid funding. This may also be unintentional, as LMICs tend not to have comprehensive/connected health data systems; a crash patient may die a few days later in the hospital, and without proper documentation the medical team may not know the root cause was a road crash, or the patient has been transferred through different medical teams using different record systems.

Still, the World Health Organization releases a Global Status Report on Road Safety every 2-4 years and data has remained generally consistent without suspicious spikes or dips indicating a government administration tampering with data. The WHO’s Status Report is the “holy grail” of comprehensive global data within the road safety community and has been externally verified by UNRSC members over time with consistency to similar comprehensive evidence-gathering reports by the World Bank and OECD’s International Transport Forum. The next WHO report is expected to be released in late 2023.

WHAT ARE THE POSSIBLE INTERVENTIONS?

The following graph shows the measures or interventions that could prevent road deaths and long-term morbidity.

This list of interventions is not exhaustive, and represent those with a sound evidence base as a root cause of crashes as well as cost-effectiveness to address.

In a 2021 Victoria University Melbourne study of road safety interventions for 10-24 year-olds across 77 LMICs, researchers conducted economic modeling to discover the benefit-to-cost ratio of implementing four proven road safety interventions: seat belts, helmets, alcohol, and speed enforcement. (See study for details of each intervention assumption.) By estimating the cost of implementation and the estimated fatalities and injuries avoided, the study found that across the 77 LMICs there was a benefit-to-cost ratio (BCR) on average of 16.76, with an average $1,687,143 in costs and average $22,339,220,800 in benefits. The lowest BCR was 4.6 in Peru ($1,522,000 costs to $6,996,000 benefits), while the highest BCR was 66.6 in Comoros ($9,000,000 costs to $615,000,000 benefits).

MANDATORY SEATBELTS AND CHILD RESTRAINTS

The simple act of buckling a seatbelt is one of the most effective ways to save lives. Correctly wearing a seat-belt reduces the risk of a fatal injury by up to 50% for front seat occupants and by up to 75% for rear seat occupants.

Children wearing an appropriate restraint for their size and weight are significantly less likely to be killed or injured than unrestrained children. Rear-facing restraints for children aged 0-23 months have been shown to reduce the risk of death or injury by over 90%, and forward-facing child restraints by almost 80%, compared to being unrestrained. For children 2-12 years old, the child restraint can lead to at least a 60% reduction in deaths, and for children 8-12 years old, booster seat use has been associated with a 19% reduction in odds of injury compared to using a seat belt alone.

While 84 countries have a child restraint law, only 33 countries’ laws—representing 9% of the world’s population—meet UN best practice standards. Of these 33 countries, 85% are high-income and 15% are middle-income; no low-income countries have child restraint laws that meet best practice.

In the 2021 Victoria University Melbourne study of road safety interventions for 10-24 year-olds across 77 LMICs, seatbelt usage was seen to avoid fatalities by 7-65% and injuries by 8-77%, with an average cost range of $0.09 to $1.45 per capita (2016 USD).

MANDATORY HELMET LAWS

The use of helmets in two and three-wheeled motorcycles has proven to be a good tool, reducing the risk of death by 42% and the risk of severe head injury by 69% the risk of a severe head injury. For example, Vietnam made motorcycle helmets mandatory in 2007, an estimated 90,500 DALYs were averted (due to prevented deaths and nonfatal injuries) within the first year of the law with a cost-effectiveness ratio of $1,249/DALY, close to the GDP per capita in Vietnam. (Though estimates of $469/DALY and $769/DALY were reported elsewhere.) By the end of 2008, the country saw a 24% decrease in injuries and 12% decrease in fatalities due to road crashes. After 10 years of the helmet law, a 2017 report found that 500,000 head injuries and 15,000 fatalities had been averted by the law, saving an estimated $3.5 billion USD in medical costs, lost labor output, and welfare loss.

Only 49 countries have helmet laws that align with best practice. Even within those, many nations do not have any laws requiring children to wear helmets while riding on motorcycles or bicycles, and enforcement is often lax or can be waived with a bribe.

In LMICs, it can be common to see helmets for sale at the local outdoor market or sold along the road. However, these are often cheap flimsy pieces of plastic rather than serious protection tools, mass produced (and sometimes counterfeiting quality standard stickers) for a quick buck. (A recent study in Vietnam found that only an estimated 10% of helmets being worn on the street would pass an impact absorption test.) Even if a country has mandatory helmet law, serious work is needed to (a) enforce that law, and (b) enforce quality of helmet worn to offer real protection. This can be complemented by awareness campaigns so buyers know how to identify a high-quality helmet, crack downs on counterfeit manufacturers, and the private sector or government subsidizing helmet costs.

In the 2021 Victoria University Melbourne study of road safety interventions for 10-24 year-olds across 77 LMICs, mandatory helmet use was seen to avoid fatalities by 20-42% and injuries by 18-54%, with an average cost range of $0.011 to $0.49 per capita (2016 USD).

ANTI-SPEEDING POLICY & INFRASTRUCTURE

According to theWHO, a 5% speed reduction can reduce the risk of fatalities by 30%. Of course, the risk of death and injury will look different for various crash scenarios. For pedestrians hit by car fronts, the risk of death increases rapidly, jumping 4.5x as likely to die between being hit by a car at 50 km/h and one at 65 km/h. In car-to-car side impact crashes, the car occupants have an 85% likelihood of death at 65 km/h.

While 169 countries have national speed limit laws, only 46 countries’ speed laws align with best practice. Enforcement plays an important role for speed limits, and while fixed speeding cameras are highly cost-effective in the long run, only upper-middle and high-income countries can afford the upfront costs of installation.

Anti-speeding infrastructure is one of the most effective ways to keep people safe. While there may be a high upfront cost to road construction, these tend to be the most cost-effective in the long run since kinetic obstacles necessarily slow down vehicles without relying on human choice. That said, basic road upgrades such as a speed bumps, “slow down” markings, and reduced speed limit signs are relatively cheap to implement. These can be stopgaps for slowing down traffic in the meantime before a government is ready to integrate more expensive road design projects.

In the 2021 Victoria University Melbourne study of road safety interventions for 10-24 year-olds across 77 LMICs, speed enforcement was seen to avoid fatalities by 17-25% and injuries by 6-56%, with an average cost range of $0.011 to $2.37 per capita (2016 USD).

DECREASE DRINK DRIVING

The WHO estimates that up to 35% of all road crashes involve alcohol, but also notes that alcohol in connection with crashes is drastically underreported. (Consider that a police officer who arrives to a crash scene with dead bodies is not trained to take the BAC of someone already deceased; similarly, a crash victim who makes it to the hospital may have a much lower BAC—or zero—by the time they arrive.) Globally, an estimated 370,000 deaths are due to road injuries after consuming alcohol. Strictly enforcing an effective drink-driving law can reduce the number of road deaths by 20%.

While any amount of alcohol has been shown to impair driving behavior, there is an exponential increase in risk for levels exceeding 0.05 g/dl. Reducing blood alcohol concentrations (BAC) from 0.1 g/dl to 0.05 g/dl may contribute to a 6-18% reduction in alcohol related road fatalities. Best practice recommends that countries also legalize a limit of 0.02 g/dl for young and novice drivers to account for lower alcohol tolerance and disproportionately higher risk of being involved in fatal crashes. While nearly all countries have a drink driving law, not all include a BAC limit which makes enforcement difficult. Of the 174 countries with laws, 136 provide BAC limits, and only 45 countries’ laws align with best practice criteria.The WHO estimates that 26.5% of all 15-19 year-olds are current drinkers, amounting to 155 million adolescents. Heavy Excessive Drinking (HED) peaks at the age of 20-24, and for all young people 15-24 years-old, when they are current drinkers, they often drink in HED sessions. The WHO finds that women tend to drink less often than men, and when they do drink, they drink less than men. That said, in the event of a crash, women are 20%-28% more likely than men to be killed and 37%-73% percent more likely to be seriously injured after adjusting for speed and other factors. This is primarily due to women tending to be smaller, plus the cultural norm of men desiring bigger, bulkier vehicles which do provide better protection in a crash.

In the 2021 Victoria University Melbourne study of road safety interventions for 10-24 year-olds across 77 LMICs, legal constraints on alcohol use was seen to avoid fatalities by 3-48% and injuries by 3-48%, with an average cost range of $0.15 to $2.24 per capita (2016 USD).

PEDESTRIAN, BICYCLE, AND MOTORCYCLE FRIENDLY INFRASTRUCTURE

Typically, roads are designed for cars and shipping trucks. Many young people in LMICs travel by foot, bicycle, or low-cc motorbike (scooter) due to their affordable cost and age limits on driving licenses. However, there is particularly poor infrastructure for these vulnerable modes of transport in LMICs, exposing young people to additional risk.

The International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP) uses satellite imagery, traffic flow data, and field imaging to determine how “safe” any given kilometer of road is for different types of transport on a 5-Star Scale. (Wherein 1 star is least safe and 5 stars are most safe.) Based on a 358,000km sample of roads across 54 countries, 1-2 star roads are the default for 88% of pedestrians travel, 86% of bicycle travel, and 67% of motorcycle travel.

Making a road safe is one of the most effective ways to keep people safe. While there may be a high upfront cost to road construction, these tend to be the most cost-effective in the long run since kinetic obstacles necessarily slow down vehicles without relying on human choice. That said, basic road upgrades such as a crosswalk, speedbumps, “slow down” markings, reduced speed limit sign, stop signs, and painted sidewalk extension are relatively cheap to implement. These can be stopgaps for slowing down traffic in the meantime before a government is ready to integrate more expensive measures like raised crosswalks, separated motorcycle and bike lines, traffic lights, extended sidewalk curbs, intersection midway pedestrian rests, and gated midway lines to prevent jaywalking.

DEVELOP AND ADVOCATE FOR UNIVERSAL SCHOOL ZONES

The concept of a “school zone” is a relatively privileged one, as these are not a given infrastructure tool in many LMICs. In LMICs, a school needs to be as accessible as possible to the surrounding community, which can often lead to schools being built on national highways and shipping routes so that as many towns as possible have road access to the school. Understandably, these roads are not ideal for children to travel to school, particularly if they need to commute without a parent.

There has not yet been a coordinated global movement to define what a “school zone” looks like and what infrastructure it includes. However, common guidance from developed nations indicates that the road environment around a school should include a lower speed limit (no more than 30 km/h), crosswalks near the school entrance gate, gated midway barriers to prevent jaywalking, gated sidewalks separate from the road, and speed-calming measures such as speed bumps or rumble strips.

School zones have the extra perk of focusing all of the investment and benefits of safer road infrastructure directly to children and their families.

GLOBAL ADVOCACY

Nearly 85% of the world’s countries lack adequate laws to counter the growing rates of road traffic deaths and injuries. The enactment of a strong, effective road safety policy is an important victory. However, it can be a long road to pass new laws, and each country will have its own barriers and nuances to lobbying. Given that government advocacy tends to take many months—or even years—of concerted effort by well-connected actors, this is one of the least cost-effective solutions to the road crisis. Yet this paper would be remiss to ignore the wide-reaching, often immediate life-saving effects of a well-crafted and enforced change in policy.

To become more cost-effective, advocacy work can be pushed through global organizations and multilateral institutions. When the UN established the UNRSC, included road safety targets in the Sustainable Development Goals, and declared the Decade of Action for Road Safety, this represented a noticeable change in governments taking proactive steps to learn about best practices and face pressure to align with them. This can also be done by the private sector and philanthropic sector. When Bloomberg Philanthropies announced it would dedicate funds to an Initiative for Global Road Safety, LMICs were jumping at the chance to participate, indeed proving their willingness to make programmatic and policy changes in exchange for development funding.

However, passage of a law doesn’t signal the end of a policy campaign. The law must be effectively implemented to achieve its intended goals. A separate implementation campaign to build and maintain political and public support, employing many of the same advocacy strategies and tactics needed to pass a policy, is often required to ensure the law can, and will be, followed.

PUBLIC AWARENESS AND EDUCATION

It is of utmost importance for stakeholders to invest in improving education and awareness outcomes in relation to road safety. Changing behavior begins with changing awareness, and the facts often speak for themselves. It is critical to ensure that leading risk factors are made well-known to road users, such as:

The use of helmets in two and three-wheeled motorcycles has proven to be a good tool, reducing risk of death by 42% and risk of severe head injury by 69%.

Wearing a seatbelt reduces risk of death by up to 50% in the front seat and up to 75% in the back seat.

For children, the child restraint has proven to be effective in reducing the risk of fatality by 60%, especially when using a booster seat belt and positioned on the rear seat.

In the event of a new safety law passed by the government, an awareness campaign is critical because it can (a) increase self-compliance, and (b) reduce the risk of public backlash. It is important to reach the public with clear messages to raise awareness about the new law and its benefits and to educate them about the specifics of where it applies, the date it takes effect, and penalties for non-compliance.

WHO IS ALREADY WORKING ON IT?

A chart of global stakeholders and major players according to stakeholder type can be found below:

| Stakeholder Type | Description of Role |

| International Organizations | International organizations play a key role in working with countries to help them achieve their public policy goals and objectives. These organizations facilitate cooperation among their members to promote partnerships that transcend borders to address global issues, including road safety. |

| Major Players | |

World Health Organization (WHO): Provides technical support to global road safety strategies by assessing and revising legislation; building capacities of lawyers to advocate for evidence-based road laws and regulations; and engaging journalists to promote road safety stories focused on change and solutions. Global road safety data and reports are available through the WHO Global Health Observatory. United Nations: Develops global road safety strategy to assist countries in implementing national road safety systems and provides funding to low- and middle-income countries through the United Nations Road Safety Fund (UNRSF). UN Environment Programme (UNEP): UNEP promotes policy and technical solutions for active mobility, and provision of pedestrian and cyclist infrastructure, including safe to school components. Its Partnership for Clean Fuels & Vehicles is working with authorities to improve fuel quality and vehicle standards to improve local air quality. United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR): Offers face-to-face and online training opportunities aimed at enhancing the capacity of government authorities, law enforcement officers and key stakeholders on road safety management and leadership. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): Works to address road fatalities involving school-age children and adolescents by funding and supporting improvements in road safety infrastructure near schools and engaging governments to strengthen policies on child road traffic injury. | |

| Stakeholder Type | Description of Role |

| Bilateral Development Agencies, Multi-lateral Development Banks | Multi-lateral development banks provide funding or technical and advisory assistance in line with development priorities. Projects funded by development banks may focus on construction or engineering of road infrastructure, capacity-building of governments to promote road safety management, and funding to ensure the transport needs of vulnerable populations (e.g. the poor, women and the elderly, individuals with disabilities) are being met. |

| Major Players | |

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB): AIIB aims to promote inter-connectivity and economic integration in Asia, through supporting the development of infrastructure and other productive sectors, including energy and power, transportation and telecommunications, rural infrastructure and agriculture development, water supply and sanitation, environmental protection, urban development and logistics. The Prospective Founding Members (PFMs) of AIIB include all ten ASEAN Member States. Asian Development Bank: Provides technical assistance and funding to promote road safety engineering and safer behaviors. Projects supported include construction of road infrastructure and development of road safety management capacity, with a focus on developing member countries. Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID): AusAID manages the Australian Government’s official overseas aid program. Its objective is to help developing countries reduce poverty and achieve sustainable development. China Development Bank: The China Development Bank operates as a state-owned development bank and is the world’s largest development finance institution. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH (GIZ): German development agency that provides services in the field of international development cooperation, including promoting safer transport for garment and textile factory workers in Asia. Department for International Development (DFID): The Department for International Development is a United Kingdom government department responsible for administering overseas aid. Its priorities include global peace, security and governance; crisis response and resilience; global prosperity; and addressing extreme poverty to help the world’s most vulnerable communities. DFID operates in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. DFID supports road safety interventions, including the Global Road Safety Facility, and provides funding to build the capacity of national level road safety agencies. EuropeAid Development and Cooperation: EuropeAid is responsible for designing EU development policies and delivering aid through programs and projects across the world. French Development Agency (AfD): The AFD is France’s development agency and focuses on climate, biodiversity, peace, education, urban development, health and governance. Under the agency’s Mobility and Transport focus are 4 priority areas: 1. Promoting livable and inclusive cities, 2. Developing the potential of national territory, 3. Integrating economies into global trade, 4. Accelerating the energy transition. Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA): JICA is a government agency that coordinates Japan’s official development assistance. JICA currently has 20 thematic issues, ranging from education and social security to transportation and urban and regional development, and poverty reduction. JICA has supported road safety measures, including conducting a study on road safety situations in developing countries. Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA): KOICA is a government agency which aims to combat poverty and support the sustainable socioeconomic growth of partner countries. Its primary sectors include Education, Health, Governance, Agriculture and Rural Development, Water, Energy, Transportation, STIA (Science, Technology, and Innovation), Climate Change Response, and Gender Equality. Under its Transportation sector, KOICA has 3 objectives in alignment with UN SDGs: the objectives are: 1)Improving access to transport systems and assisting economic and industrial development, 2) Developing an environmentally-friendly and safe transport system, 3) Serving a more active role in development financing. New Zealand Agency for International Development (NZAid): The New Zealand Aid Programme is the New Zealand Government’s international aid and development agency. The geographic focus for NZaid is the Pacific region, where it invests 60% of its development funding. In its Asia programming, NZaid focuses on agriculture, education, governance, renewable energy, and disaster resilience. Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida): SIDA is a government agency of the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs responsible for supporting Sweden’s Policy for Global Development (PGU). SIDA has several focus areas, ranging from health and education to sustainable societal development and market development. SIDA has funded the Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP) since 2000. SIDA aims to transfer knowledge and build capacity in developing countries to apply and adapt Vision Zero principles in their settings. United States Agency for International Development (USAID): Independent aid agency of the U.S. federal government with missions in over 100 low-income countries in regions including Africa, Asia, Latin America, Middle East, and Eastern Europe. In the field of road safety, USAID supports strengthening of road infrastructure with provision of funding and technical assistance and capacity building of government bodies and road authorities. World Bank: Through the Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF), a multi-donor fund, the World Bank provides funding and support for governments in low- and middle-income countries to develop their road safety management capacity and scale up road safety delivery. | |

| Stakeholder Type | Description of Role |

| Research Institutions and Academia | Research institutions and academic institutions provide scientific and evidence-based research on road safety on areas of interest such as road user behavior; international road policies, implementation, enforcement, and outcomes; safer roads and vehicles, and other topics of concern. Research institutions may present findings to governments in the aim of promoting evidence-based road safety policies and strategies. |

| Major Players | |

US Centers for Disease Control & Prevention—National Center for Injury Prevention & Control (U.S. CDC): Provides technical and funding support for road safety research, including WHO reports, documents, and technical packages to promote evidence-based road safety interventions. Johns Hopkins International Injury Research Unit (JHIIRU): Research unit established within the Johns Hokins Bloomberg School of Public Health which publishes scientific papers on global road safety. JHIIRU is actively involved in the Bloomberg Initiative for Global Road Safety (BIGRS) in 10 cities to find proven solutions through road safety interventions. The George Institute for Global Health Australia: An Australia-based research institute which conducts research on several health priorities, including road crash injuries. Its research teams study global measures including laws on speed, seatbelt wearing, motorcycle helmet use and driver licensing. World Resources Institute: Works with cities across the world to implement safe system street design principles, as a leading global advocate for safe and sustainable, low carbon, urban mobility. | |

| Stakeholder Type | Description of Role |

| National Governments and State/Municipal Agencies | National governments and road agencies are responsible for funding, planning, designing and operating road networks, such as road infrastructure; managing vehicle registration and driver licensing systems; and regulating and enforcing road user behaviors. Governments provide the legal frameworks in which all road safety stakeholders operate, ranging from traffic authorities to the population of road users, and thereby serve as a high-priority target for advocacy, dialogue, and cooperation. |

| Major Players | |

Information on road safety legislation, national action plans and strategies, and other relevant updates may be found on government portals and websites. Online research may be conducted on:

| |

| Stakeholder Type | Description of Role |

| Philanthropies, Foundations, Private Sector | Philanthropic foundations provide financial contributions, often in the form of grants, to support projects and interventions addressing development issues prioritized by their founding company, board, or major donors. In addition to funding projects, foundations may coordinate volunteering time to support projects and activities. Private sector stakeholders establishing foundations can fall into the following categories:

Private sector volunteers who support a foundation’s work can include:

|

| Major Players | |

Bernard Van Leer Foundation: The Bernard Van Leer Foundation funds and shares knowledge about work in early childhood development. The foundation has an Urban95 initiative which focuses on how urban planning interacts with child development. Through Urban95, the foundation has implemented several road safety projects, including safer roads to school in Mexico city with a data mapping tool to engage parents and city authorities, among other projects in its Urban95 cities. Bloomberg Philanthropies: Bloomberg Philanthropies launched the Bloomberg Philanthropies Initiative for Global Road Safety, which has dedicated nearly $260 million to reduce road traffic fatalities and injuries in low- and middle-income countries. The initiative focuses on The Bloomberg Philanthropies Initiative for Global Road Safety focuses on improving road safety laws in 5 countries and on and implementing evidence-based interventions in 10 cities. Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA): The FIA is a global association representing motor organizations and motor car users, and is the governing body for auto racing events, such as Formula One. The association joins 243 international motoring and sporting organizations from 146 countries. The FIA leads its FIA Action for Road Safety campaign, in support of the Decade of Action (2011-2020), which involves high-level advocacy, road safety programming at the local level through its clubs network, mobilizing its motor sport community, and various campaigns and partnerships, such as online pledges for road safety in partnership with institutional and corporate stakeholders. FIA Foundation: A UK-based international charity hosts and coordinates global road safety initiatives. In addition to providing funding support to each of the other partners, the Foundation also supports the following global and regional partners delivering applied research, legislative campaigns and advocacy focused on child health and mobility. Its road safety work and global initiatives can be found here. Fondation Botnar: A Swiss-based foundation which focused on the use of AI and digital technology to improve the health and wellbeing of children and young people in growing urban environments. The foundation focuses on supporting research and investing in emerging technologies with scalable solutions. The UPS Foundation: The UPS Foundation was one of the first private sector companies to join the United Nations Decade of Action on Road Safety, launched in 2011. With its fleet of thousands of UPS drivers on the road every day, UPS prioritizes safe driving in its CSR work. | |

| Stakeholder Type | Description of Role |

| Civil Society Organizations | In the road safety sector, civil society organizations include development NGOs, road safety coalitions, unions, advocacy groups, and the media. Road safety organizations and groups in the civil society sphere can:

|

| Major Players | |

AIP Foundation: A nonprofit dedicated to decreasing road crash casualties in low- and middle-income countries by providing safety interventions to vulnerable road users. Projects are centered around 5 interconnected approaches: public awareness campaigns, global & legislative advocacy, targeted education, research and evaluation, and access to safe equipment. Amend: Road safety work includes population-based scientific studies and evaluations, community-based road safety programs, advocacy, light infrastructure, media campaigns, and the social marketing of reflector-enhanced schoolbags. Global Alliance of NGOs for Road Safety: The Alliance is a collection of nongovernmental organizations that implement programs and lobby for road safety initiatives around the world. As an umbrella organization, it currently represents more than 200 member NGOs from 90-plus countries. Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP): Creates and supports multi-sector road safety partnerships and program coordination at the global level in Asia, the Americas, Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. Projects focus on key risk factors such as helmets, seat belts, drinking and driving, speed management and vulnerable road users. Supports the and for a new Child Road Safety Challenge funded by Fondation Botnar. International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP): iRAP (the International Road Assessment Programme) is the umbrella programme for Road Assessment Programmes (RAPs) implemented worldwide in over 100 countries. iRAP develops various tools for risk mapping, conducting star ratings for school safety, and policy and performance tracking with a focus on cost-effectiveness and informing government investments in road safety. International Road Federation: Headquartered in Washington, D.C., IRF assists countries in progressing safer ad smarter road systems, with a focus on providing advisory assistance, advocacy, and education programs. IRF brings together public and private sectors of the road and transport industry in its global network for information exchange and business development. National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO): The National Association of City Transportation Officials is a coalition of the Departments of Transportation in North American cities. NACTO has a Streets for Kids program as part of its Global Designing Cities Initiative, focused on developing a child-centered design guide and applying child-focused strategies in 12 cities. Plan International: Plan International is a development and humanitarian organization which works in 71 countries across the world, in Africa, the Americas, and Asia to advance children’s rights and equality for girls. Plan International also works to secure safer cities “with and for girls.” Its initiatives have included awareness-raising activities with youth in Hanoi, Vietnam, where youth representatives distributed educational comics at bus stops to raise awareness around harassment of women on public transport. Safe Kids Worldwide: A global nonprofit aimed at protecting children from preventable injuries with 400 network members in the U.S. and partners in 33 countries with a focus on research, educational programs, and public policy. Save the Children: An international NGO for child rights and welfare which advocates for safe mobility rights for children. Towards Zero Foundation: The Towards Zero Foundation (TZF) is a UK-registered charity which serves as a cooperative platform for organizations committed to the application of the Safe System approach to road injury prevention. One of TZF’s main projects is the Global New Car Assessment Programme (Global NCAP) which aims to support the universal adoption of the United Nation’s vehicle safety standards worldwide. Youth for Road Safety (YOURS): A global organization aimed at making the world’s roads safe for youth and a member of the United Nation Road Safety Collaboration (UNRSC). The organization focuses on developing youth champions from around the world through awareness campaigns, workshops, and engagement in global advocacy. | |

WHY MIGHT A NEW PHILANTHROPIST WISH TO GET INVOLVED?

Road safety is an attractive new cause area because it connects to many other important development areas. A safe road journey for young people has implications for:

Climate change through efforts to reduce vehicle emissions and improve air quality

Global health outcomes due to pedestrian and bicycling safety, as well as avoided healthcare burden from crashes

Poverty inequality due to poor communities’ disproportional exposure to road crashes and cycle of poverty after a crash

Education access due to unsafe journeys to school, particularly for children of working parent(s) who must get themselves to school

Women’s equality due to women being the primary caretakers in the event of a child’s crash, which removes women from the workforce, limits social equity, and perpetuates disadvantage for single mothers

Smart cities and technology due to emerging innovation for transportation systems, urban planning, and government enterprise data reform

Supply chain and manufacturing due to the impact of shipping/hauling routes on LMIC roads, particularly with many of the world’s outsourced factory production lines in LMICs

Consumer protection rights due to the need for vehicles, helmets, and restraint systems to be built according to high safety standards and be available/affordable in the marketplace, particularly for affordable high-quality vehicles

We cannot overemphasize that this is the number one cause of death for people under 30 years old—52% of the world’s population, 90% of whom live in LMICs—but is generally ignored in developed nations or written off as inevitable. The world must pay attention and take action.

KEY UNCERTAINTIES

Road safety interventions tend to be measured by their success in preventing fatalities and/or injuries. It is less common to measure results in the metrics most common to the Effective Altruism platform, such as DALYs, cost-to-benefit ratios, odds ratios, or social welfare improved (in $). This makes road safety a difficult issue for which to directly compare results to other issue areas.

A country’s road infrastructure and driving norms may look drastically different from its neighbor’s (and even cities within a country may look different). This means road interventions must be quite tailored to the local context, and there is not a one-size-fits-all global solution. Much like in business, the more you need to customize a product for individual consumers, the smaller your profit margin. That is, tailoring road safety interventions is expensive and time consuming with diminishing cost-effectiveness as you scale. However, in the case of most road crisis interventions, customization is crucial.

Depending on a country’s driving norms, there may be public backlash to harsher road regulations. For example, if someone’s daily commute is on a 60 km/h road near a school, and the new school zone speed enforces a 30 km/h limit, that person’s commute gets a lot more inconvenient and backed-up. Governments will need support from other actors to implement proper public awareness campaigns lobbying for public buy-in to avoid political backlash or outright refusal to comply.

- ^

Cars represent 29%, and the remaining 17% were ‘unidentified’ in police/medical records, meaning it is likely to include non-car drivers and passengers. (WHO, 2018)

- ^

Between 2010 to 2016 (the latest comprehensive road death/injury survey by WHO), road fatality rates increased in Africa and Southeast Asia; remained stable in the Americas and Eastern Mediterranean; and decreased in Europe and the Western Pacific. The global average for road safety fatalities remained stable.

- ^

To achieve these welfare gains the report lists interventions that include reducing and enforcing speed limits, reducing driving under the influence of alcohol, increasing seat-belt use through enforcement and public awareness campaigns, and integrating road safety in in all phases of planning, design, and operation of road infrastructure.

For anyone interested in pursuing this further Charity Entrepreneurship is looking to incubate a charity working on road traffic safety.

Their report on the topic can be found here: https://www.charityentrepreneurship.com/research

Congratulations! This is a very well-written and educational piece on low- and middle-income countries’ current road safety issues. Living in Vietnam myself, this is an area where I and many others would be glad to see more attention and active involvement from global players to address and improve. I liked the section “Who is already working on it”, a comprehensive summary of what is being done by whom to solve the problem.

I wish you very good luck with the initiative.

A well researched paper on a pernicious issue that needs to be addressed urgently.

A truly eye-opening read. Thank you for your contribution to this important cause affecting youth worldwide.

Well Written and very informative!