How to Become a World Historical Figure (Péladan’s Dream)

I. Introduction

Erik Hoel writes the following in reference to Roger’s Bacon’s Predictions for 2050: Black Swan Edition post (apologies if you’ve read this before, feel free to skip to the next section).

“Finally, there’s Secretum Secretorum, which eschews the idea of extrapolating from current trends and instead takes some big contrarian positions. Of particular interest is the idea of a “World Historic Individual” emerging. Specifically that

. . . by 2050 there will a living person who is widely recognized to be what early 1900s German historian Oswald Spengler called a “World Historical Figure” (The Decline of The West). Jesus, Socrates, Alexander the Great, Buddha, Genghis Khan, Muhammed, Newton, Darwin are all on the list.

It’s always struck me that my generation, the millennials, have grown up with a particular lack of World Historic individuals (in terms of impact in the long march of history, not popularity or name recognition in the moment). We missed concurrency with most of the 20th-century luminaries. My parents’ early lives overlapped with Einstein, for instance. Indeed, it’s worth asking:

Who is the most recent person that could reasonably be called a world historical figures? I say yes for Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. . . . After that. . . I’m not so sure. Off the top of my head, here’s a list of potential candidates: Mao Zedong, Osama Bin Laden, Obama, Trump, Elon Musk (sorry Bezos, you didn’t make the cut), and Xi Jinping. I think most of these people are debatable when you start to consider truly vast time horizons: what are the chances people will know about Obama, Xi, or Elon Musk 500 years from now?

Of those listed by Secretum Secretorum, the only individual I can imagine mattering in five hundred years is Elon Musk, although not for anything he’s done yet. But if he did establish a city on Mars, as there’s indeed a chance he might, getting humanity off-planet would certainly be remembered. Yet, it’s also possible the responsibility for the actual settlement of Mars will be spread out over the entire space industry, not to mention over various governments, ensuring no lasting historical credit goes to Musk.

So where are the Einsteins? Or Joans of Arc? The Ghandis? Let alone the Leibnizs or Napoleons or Christs? Perhaps there is someone unknown to us, some little girl waiting in the wings who will change everything. A comforting thought. For it is only in the brief periods when a World Historical individual bestrides the globe that humanity is no longer alone in the universe.

Right now we are children in a dark room, waiting for the hallway light to turn on and an adult to come save us. Some of us may live our whole lives in this dark.”

II. Ambition

I struggled mightily with how to preface this declaration, how I might frame it in a clever manner which concisely conveys the utter seriousness with which I make it while also subtly gesturing towards the absurd grandiosity of such an announcement. In the end, I came to the conclusion that I am incapable of conceiving of a verbal permutation that will satisfy me, and that I must simply make the declaration without preamble.

I want to be a World Historical Figure.

I want to be the Adult who leads us out of the Darkness.

There seems to be an intuition that something has shifted, that for a multitude of reasons it is now much more difficult to become a World Historical Figure than it was in previous eras (not that it was ever easy obviously). An individual going by the name of Batislu gives voice to this view in a comment on Hoel’s post.

The great people of past times lived in ages of informational scarcity compared to today…Now, our attention is splintered into thousands of eclectic directions every single day. There is so much noise, so many viewpoints from every vantage, that the half-life of an individual’s existence in our collective attention has shrunk and will continue to do so until all prominence is nothing but a fleeting blip, swallowed by the next thing as quickly as came to the forefront.

There’s a second factor that compounds this: as time goes on, it becomes harder and harder to accomplish things that are meaningfully differentiated from what came before. This follows the simple logic that “what came before” is growing larger but there’s only a finite amount of easy pickings of meaningfully differentiated accomplishments in the future. In the past, a single mind could discover relativity. Now a CERN paper will have thousands of co-authors and rely on billions of dollars of tax-payer funded instruments. Times have changed.

Indeed, times have changed, but not for the reasons Batislu thinks. We’ve never been less ambitious than we are now, never more cynical about the possibility of Greatness. Oh sure, we have our Musk’s, our Bezos’s, our Putin’s (even though he doesn’t actually exist), our Xi’s, but theirs is such a shallow, puerile ambition. Musk may take us to Mars and any living or future dictator may conquer the world, but then what? The same problems on a new planet, the same business but with new management.

Still, nothing new under the sun.

Still, time is a flat circle.

What we lack, which we didn’t before, is the most profound kind of ambition, an ambition to turn the flat circle into an ever-ascending spiral, to bring genuine novelty into this mortal plane, to emancipate us from this fallen realm. This ambition is an unquenchable thirst for spiritual awakening, for deliverance, for transcendence, not just for one’s self but for all of us—the was, the is, and the yet to be.

Precious few have ever realized this aspiration (Zoroaster, Buddha, Pythagoras, Jesus, Muhammed, Martin Luther, amongst others), but precious few of us today even try. Consequently, you have virtually no competition and it is in fact easier than ever to ignite a spiritual revolution (conversely, there is zero alpha left in anything material or digital; stop wasting your precious time—you will not “revolutionize” finance, the internet, or industry). In response to Batislu’s truly cynical comment that you read above, commenter RockyLives writes:

If WHFs were to cease appearing from the present age onwards, this would represent an unprecedented break with an aspect of humanity that we can trace back at least to antiquity. Are we really so convinced of the exceptionalism of our time that we think an unbroken continuum stretching perhaps six thousand years will now be severed?

The shrinking half life of an individual’s ability to command our attention continues only until an exceptional individual bucks the trend.

So what does this mean in practice? Quite possibly that a new WHF will come from somewhere completely unexpected (not from politics, from the established religions or from the increasingly-collaborative fields of advanced scientific research). Most likely it will be someone whom we cannot anticipate because they are (to quote Rumsfeld) “an unknown unknown” coming from a place none of us expected.

I want to be the unknown unknown.

I know it’s hard for you, dear reader, to wrap your shriveled, smooth brain around this level of ambition; even now, you think this to be a joke, a gimmick, a stunt.

“Surely, he can’t be serious. I’m not even sure what he’s talking about really—like we all should go out and try to start a cult or something?

Yes, but no—the whole pejorative notion of a cult is a psyop that They use keep us under their thumb, to keep us docile and servile (and if you have to ask who They are, you’ll never know).

You need to aim higher.

Do not create a religion, create an entirely new domain of activity and inquiry—something that is not religion, science, philosophy, or art but somehow all of them and none of them.

“Pick someone at random & convince them they’re the heir to an enormous, useless and amazing fortune—say 5000 square miles of Antarctica, or an aging circus elephant, or an orphanage in Bombay, or a collection of alchemical manuscripts. Later they will come to realize that for a few moments they believed in something extraordinary, and will perhaps be driven as a result to seek out some more intense mode of existence.”

Do this, but for all of us, forever.

They will tell you that “Utopia is that which is in contradiction with reality”, that “Utopias rest on the fallacy that perfection is a legitimate goal of human existence”, and that we must “Abandon all hopes of utopia—there are people involved”. Well then the problem is not with utopia but with humanity and reality. Take the quarks, the genes, the neurons and the neutrons, time and space, take them into your bare hands and forge a new species and a new universe, a perfect one in which all beings walk hand-in-hand towards that which should be called God, eternally.

“You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven. He causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous. If you love those who love you, what reward will you get? Are not even the tax collectors doing that? And if you greet only your own people, what are you doing more than others? Do not even pagans do that? Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.”

In saying “Love thy enemy”, Jesus, bless his sweet heart, gave us a simple, yet radical message through which we could break free from the bloody wheel of history (an eye for an eye for an eye for an eye for an eye…) and bring about the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth.

Be like Jesus, but more so—do not fail as he did. Create a message, a vision, which will not and cannot be corrupted.

Jesus died for all of our sins, but who will die for his?

(Look, I’m not saying that Christianity wasn’t the greatest start-up of all time and that Jesus wasn’t a helluva founder, we just simply have to believe that we can do better.)

III. Péladan’s Dream

It may be helpful at this point to bring it back down to earth a bit and provide an example of an individual who, in his own idiosyncratic way (to put it mildly), tried to become a World Historical Figure. From his story, we may draw inspiration and derive a few lessons which will help us in our pursuit of the same goal.

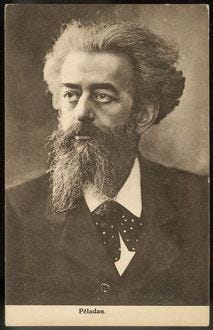

In the Paris of the 1890s, at the height of the Decadence, the man of the moment was the novelist, art critic, and would-be guru Joséphin Péladan, who named himself Le Sâr, after the ancient Akkadian word for “king” (he claimed that a Babylonian king left the title to his family). He went about in a flowing white cloak, an azure jacket, a lace ruff, and an Astrakhan hat, which, in conjunction with his bushy head of hair and double-pointed beard, gave him the aspect of a Middle Eastern potentate. He was in the midst of writing a twenty-one-volume cycle of novels, titled “La Décadence Latine,” which follows the fantastical adventures of various enchanters, adepts, femmes fatales, androgynes, and other enemies of the ordinary. His bibliography also includes literary tracts, explications of Wagnerian mythology, and a self-help tome called “How One Becomes a Magus.” He let it be known that he had completed the syllabus. He informed Félix Faure, the President of the Republic, that he had the gift of “seeing and hearing at the greatest distances, useful in controlling enemy councils and suppressing espionage.” He began one lecture by saying, “People of Nîmes, I have only to pronounce a certain formula for the earth to open and swallow you all.”

—Alex Ross, “The Occult Roots of Modernism”

Quite the character, eh? He also apparently changed his name from Joseph to Joséphin and described himself as “the sandwich-man of the Beyond” and I’m not sure why he did either of these things but I’m just happy that he did. Strangeness aside, this all sounds much more like a garden-variety cult leader than a titan of history. We will get to Péladan’s shot at glory in a moment, but first, a little more background—how did such a person come to be?

Joséphin Péladan was born in Lyon, in 1858, into a family steeped in esoteric tendencies. His father, Louis-Adrien, was a conservative Catholic writer who tried to start a Cult of the Wound of the Left Shoulder of Our Saviour Jesus Christ (note: so his father was an attempted cult leader—checks out). Péladan’s older brother, Adrien, was the author of a medical text proposing that the brain subsists on unused sperm that takes the form of vital fluid (note: lol wut). When Adrien died prematurely, of accidental strychnine poisoning, his brother perpetuated his ideas, suggesting that the intellect can thrive only when the sexual impulse is suppressed. The political views of the Péladans were thoroughly reactionary; they disdained democracy and called for the restoration of the monarchy. Péladan differed from many other occultists in insisting that his Rosicrucian rhetoric was an extension of authentic Catholic doctrine, which Church institutions had neglected (note: much more on Rosicrucianism below).

Ibid

In 1882 he came to Paris where Arsene Houssaye gave him a job on his artistic review, L’Artiste. In 1884 he published his first novel, Le vice suprême, which recommended the salvation of man through occult magic of the ancient East. His novel was an instant success with the French public, which was experiencing a revived interest in spirituality and mysticism. (Wikipedia)

Now, Péladan’s bid for greatness, his attempt at becoming a World Historical Figure; I’ll have to unpack these two passages quite a bit as they don’t even really begin to elucidate the grandness of his dream.

In 1890, he established the Order of the Catholic Rose + Croix of the Temple and the Grail, one of a number of end-of-century sects that purported to revive lost arts of magic. The peak of his fame arrived in 1892, when he launched an annual art exhibition called the Salon de la Rose + Croix, which embraced the Symbolist movement, with an emphasis on its more eldritch guises. Thousands of visitors passed through, uncertain whether they were witnessing a colossal breakthrough or a monumental joke. (“The Occult Roots of Modernism”)

As an art critic, Péladan had been vocal in critiquing the dominant trends in French art, which included officially sanctioned styles promoted by the academy, and the Impressionists. This resulted in a series of six exhibits of Symbolist artists and associated French avant-garde painters, writers, and musicians, as the Salon de la Rose + Croix. The Salon was enormously popular with the press and public, but failed to succeed in revolutionising French art, as Péladan had hoped. (Wikipedia)

For those who aren’t familiar with Symbolism (as I wasn’t before researching all of this).

“Symbolism initially developed as a French literary movement in the 1880s, gaining popular credence with the publication in 1886 of Jean Moréas’ manifesto in Le Figaro. Reacting against the rationalism and materialism that had come to dominate Western European culture, Moréas proclaimed the validity of pure subjectivity and the expression of an idea over a realistic description of the natural world. This philosophy, which would incorporate the poet Stéphane Mallarmé’s conviction that reality was best expressed through poetry because it paralleled nature rather than replicating it, became a central tenet of the movement. In Mallarmé’s words, “To name an object is to suppress three-quarters of the enjoyment to be found in the poem… suggestion, that is the dream.”

Though it began as a literary concept, Symbolism was soon identified with the artwork of a younger generation of painters who were similarly rejecting the conventions of Naturalism. Symbolist painters believed that art should reflect an emotion or idea rather than represent the natural world in the objective, quasi-scientific manner embodied by Realism and Impressionism. Returning to the personal expressivity advocated by the Romantics earlier in the nineteenth century, they felt that the symbolic value or meaning of a work of art stemmed from the re-creation of emotional experiences in the viewer through color, line, and composition. In painting, Symbolism represents a synthesis of form and feeling, of reality and the artist’s inner subjectivity.” (source)

So Péladan’s hope was that these salons would dislodge the dominant artistic currents of the day and move the Symbolist movement and its philosophical worldview to prominence. Certainly bold, but not exactly civilization-altering, however Péladan saw this aesthetic revolution as only the first step in a much broader transformation of culture and spirituality.

“His Salon de la Rose et Croix, though short-lived, was perhaps one of the most ambitious artistic undertakings the French art world has seen, featuring unique exhibitions and productions seeking to unite the arts into a revival of initiatory drama, with a philosophical underpinning rooted in the Western esoteric traditions, and with the ultimate goal of the spiritual regeneration of society. Central to Péladan’s vision was his conception of the artist as initiate; select individuals who could bring a small part of the divine into the mundane sphere.”

—Sasha Chaitow, “Who was Joséphin Péladan?”

“...Péladan sought revolution against realism and the re-enchantment of what he saw as a disintegrating and decadent society. Through his breakaway order he sought to merge his own occult theories with Catholic principles to establish a nucleus from which would emanate a whole set of religious, moral, and aesthetic values. Péladan’s vision was an attempt to return the soul to beauty and the innocence of Eden. His mission was the reinstatement of the Primordial Tradition, the old philosophia perennis of the Renaissance philosophers, through the ritualization of art, which in turn would function as the manifestation of the divine in matter.”

Ibid

“The purpose of Péladan’s vision was no less than a spiritual revolution with beauty as the supreme weapon and art as the coup de grace against the “disenchantment of the world’ so prevalent as first the scientific world-view and then the industrial revolution completed their conquest of the Western mind, in an age he regarded as characterized by rampant materialism and futile decadence. In his own words, at the opening of the first Salon (1892): ‘Artists who believe in Leonardo and The Victory of Samothrace, you will be the Rose and Croix. Our aim is to tear love out of the western soul and replace it with the love of Beauty, the love of the Idea, the love of Mystery. We will combine in harmonious ecstasy the emotions of literature, the Louvre and Bayreuth.’”

Ibid

V. Art and Reason

What lessons can be drawn from Péladan’s life and ambitions that can help us (you and I, dear reader) in our quest to ignite a spiritual revolution and attain World Historical Figure status? The first lesson is not a lesson per se but a recognition that his dream is not dead—there is nothing stopping us from taking up the mantle and attempting to succeed where he failed. For whatever lip service we pay to the importance of art, it is seen ultimately as a diversion in today’s culture, a luxury, one that is an integral part of the human experience perhaps, but still a diversion nonetheless. The cult of STEM is ascendant; all activities which do not “use evidence and reason to figure out how to benefit others as much as possible” are ultimately seen as trivial or misguided—you must aim to be “high impact” or you will have no impact at all (don’t even get me started on the philosophical abortion that is effective altruism). This attitude has infected the arts as well.

“I wish that future novelists would reject the pressure to write for the betterment of society. Art is not media. A novel is not an “afternoon special” or fodder for the Twittersphere or material for journalists to make neat generalizations about culture. A novel is not BuzzFeed or NPR or Instagram or even Hollywood. Let’s get clear about that. A novel is a literary work of art meant to expand consciousness. We need novels that live in an amoral universe, past the political agenda described on social media. We have imaginations for a reason. Novels like American Psycho and Lolita did not poison culture. Murderous corporations and exploitive industries did. We need characters in novels to be free to range into the dark and wrong. How else will we understand ourselves?”

—Ottessa Moshfegh (h/t to Erik Hoel from “How the MFA swallowed Literature”)

Also see “Literature Should Be Taught Like a Science” (not really hard to see why fewer people are reading literature than ever before and enrollment in humanities majors has plummeted in recent years).

The best minds of our generation are fiddling away in laboratories, twiddling around with opaque machine learning algorithms, or “thinking about how to make people click ads”. Unsurprisingly, we completely suck at art now. Two examples among many: old music is killing new music and old actors are killing younger actors (not literally, although I’m sure many of them wish they could).

We are also apparently incapable of making original movies or TV shows anymore.

Péladan would weep if he knew what we’ve become, for to him art was not mere diversion but divinity itself. If you or I could turn his dream into a reality, if we could catalyze a movement which made art not an accessory to spirituality but its prime mover, a movement from which a “whole set of religious, moral, and aesthetic values” would bloom, that would be a truly epoch-defining achievement worthy of World Historical Figure status.

Although my patience with all of you shape rotators and STEMcels runs painfully thin, I suppose I should offer some kind of justification for why this is a dream worth pursuing even if one’s concerns are a bit more practical and rational. Man cannot live by bread alone, and if you give her nothing but bread she will come to disdain it and will let it spoil whilst she pursues that which she lacks—love, beauty, knowledge, adventure, transcendance. All creativity and vitality, whether scientific, spiritual, artistic, or philosophical, flows from the same head waters, and if the water of one becomes fetid and stagnant, it will become so in the others as well.

Unsurprisingly, old scientists are also killing young scientists (again, not literally, although I’m sure many of them wish they could).

One manifestation of this principle is the aforementioned obsession with being “high-impact”, something which arises inevitably from our aesthetic deficiencies. As noted above, “art is not for the betterment of society” (Ottessa Moshfegh); thus, when our artistic sensibilities atrophy, when we can no longer create beauty or appreciate it, all that is left is “the betterment of society”, a rational goal which can only be achieved through rational means. However, in enantiodromatic fashion, like the closeted preacher who violently rails against homosexuality, our obsession with evaluating all altruistic efforts and scientific projects through the rational lense of “effectiveness” (efficiency, potential for impact, level of risk, etc.) has become the epitome of irrationality.

A first problem with the purely instrumental approach is that we are not nearly as good at identifying what will be the Next Big Thing or estimating our chances of success as we think we are. To take one example, perhaps not even the best one: CRISPR, the revolutionary gene-editing technology, came from studying an obscure genetic phenomenon (a weird sequence of repetitive elements) in certain groups of bacteria (shouldn’t we have been researching something more important like cancer or aging?!?). We could have poured billions into improving gene-editing technologies (and in fact we probably did if you consider the totality of efforts across academia and industry) and not made an advance as big as CRISPR.

“Rather than attempting to demarcate the nebulous and artificial distinction between useful and “useless knowledge, we may follow the example of British chemist and Nobel laureate George Porter, who spoke instead of applied and “not-yet-applied” research.”

—Robbert Dijkgraaf, “The World of Tomorrow” from The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge

Paul Graham, of course, make this point in a short but memorable essay entitled The Risk of Discovery. We might expect that Isaac Newton, of all thinkers who ever lived, was one who was particularly good at identifying promising lines of inquiry, but yet Newton spent roughly equal amounts of time working on physics/mathematics, alchemy (something which will be discussed extensively below), and theology (i.e. searching for hidden prophecies in the Bible).

Physics seems to us a promising thing to work on, and alchemy and theology obvious wastes of time. But that’s because we know how things turned out. In Newton’s day the three problems seemed roughly equally promising. No one knew yet what the payoff would be for inventing what we now call physics; if they had, more people would have been working on it. And alchemy and theology were still then in the category Marc Andreessen would describe as “huge, if true.”

Newton made three bets. One of them worked. But they were all risky.

Let us also note here that Newton’s motivations were certainly not rational and he was decidedly not trying to save the world or better society—all three of his projects were driven by spiritual impulses.

The second problem with our overly-rational and artistically-deficient culture is that it leads to excessive conformity and groupthink. The subjectivity and irrationality (or rather non-rationality) of aesthetics is a feature not a bug when it comes to scientific/technological work because the pursuit of beauty and wonder (and love and adventure and transcendance and…) is inevitably diversifying as each person’s aesthetic sense is necessarily idiosyncratic.

(It pains to me think of how much time we waste on all of this the god-awful (and I mean that literally) metascience and progress studies “research” when all it would take to bring us out of this scientific malaise is to start evaluating grant proposals by their potential aesthetic value instead of their potential “importance” or “impact”—e.g. does this research project have the potential to help us learn something truly beautiful about nature?)

Now that I have completely satisfied the gripes and concerns of all the pedants and nit-pickers (/s), we may return to the matter at hand: the spiritual transformation of mankind and the becoming of a World Historical Figure. Although the preceding discussion was a digression, it was a useful one as it leads quite naturally into what I see as the foundational principle which we can derive from Péladan’s story:

Reason will not help us achieve our goals, and indeed it will not help anyone achieve any radical ambition; simply put: if you have unreasonable goals, then you must think and act unreasonably in order achieve them.

What is it, fundamentally, that we are trying to do? What we do not want to do is “change the world”—that would be much too difficult. What we want to do is imagine a new world and then make it a reality; in other words, we want to play make-believe and then make them believe—this will be much easier. The first step requires imagination, intuition, divine inspiration, epiphany, revelation; Reason will not help us here. The second step, “make them believe”, will require the application of some but not too much rationality, and frankly most of what will be difficult is best left to the minions (there are two types of people in the world, Visionaries and minions, however there is also a third type which recognize the falsity of this dichotomy but those people are almost always Visionaries so the dichotomy still holds). Consider Péladan—this was a man that wrote “a twenty-one-volume cycle of novels, titled “La Décadence Latine,” which follows the fantastical adventures of various enchanters, adepts, femmes fatales, androgynes, and other enemies of the ordinary” yet was also a devout catholic and staunch supporter of the monarchy; this was a man that began a lecture by saying, “People of Nîmes, I have only to pronounce a certain formula for the earth to open and swallow you all.” Did he really believe this or was he lying through his teeth? This is the wrong question, as talk of belief and lying implies that he was concerned with Truth and Reason in even the slightest. Like Péladan, we must accept contradiction and embrace the absurd and become paradox. Argumentation will achieve nothing; we must create symbols, make myths, and imagine miracles.

As Niels Bohr apparently once told Einstein, “You are not thinking; you are merely being logical”

What we must do is capture hearts and minds, two things which are irrational to their very core. This is something that marketing experts know all too well, and ultimately all that we have here is a challenge of marketing—how can we get people to buy our vision of a new world? Advertising legend Rory Sutherland rightly identifies that science (broadly construed) will not help (in fact it is a hindrance) and that what we really need is alchemy, a non-rational art in which the “opposite of a good idea can be another good idea”. To this end, he provides us with 11 rules of idea alchemy, a few of which I will briefly introduce here as they will provide us with some useful insights which we will tie together in the final section (actually there’s two more sections but who’s counting).

6. The problem with logic is it kills off magic

Once you’ve devised what seems like a logical schema for problem solving, you’ve created something which is based on very simple physics and maths—something which will always give you a single right answer. But where logic exists, magic cannot.

If you want to improve someone’s experience of a hotel, logic dictates that you improve the hotel itself, rather than the perception of the hotel. But people don’t perceive the world objectively, and assuming that they do means you will be confined to improving your product exclusively by doing objective things. Context is a marketing superweapon, and it works because it works magically.

What we need to accomplish is magical in nature, and thus we cannot use logic.

We may not be able to change reality, but we can change the perception of it.

8. Test counterintuitive things, because nobody else will

Some of the most valuable discoveries don’t make sense at first, because if they did, someone would have discovered them already. This is a bit risky of course—if you have a bonkers idea and it fails, your job may be on the line, whereas if you do something rational that fails you get to try again. But, there can be an extraordinary competitive advantage if you create a small space in your business for people to test things that don’t make sense. The great value of experimenting outside of the rationalists’ comfort zone is that most of your competitors will be too scared to go there.

We need to create a small space in which we can test things that don’t make sense.

We must tread where others fear to go.

9. Solving problems using only rationality is like playing golf using only one club

Rationality has its uses, but you will improve your thinking a great deal if you abandon artificial certainty and learn to think ambiguously about the peculiarities of human psychology. In other words, if you make assumptions on what’s important to people, and how they think, decide and act, you are basing your conclusions on a very narrow view of human motivation.

For instance, if you are selling a product and you are defining motivation to buy in economic terms, the solution logically boils down to either fining people or bribing people. Those are perfectly worthwhile solutions to behaviour change. Incentives do work. But that’s one golf club among many. There are lots of reasons why people do the things they do, and economic incentives only cover a small part of them.

“It is written, ‘Man does not live by bread alone. Rather, he lives on every word that comes from the mouth of the Eternal One.’”

11. If there was a logical answer, we would have already found it.

We fetishise logic to such an extent that we are increasingly blind to its failings. It doesn’t help that rational people are everywhere and control everything – your finance department, your procurement department, the consulting firm you hire, your government and so on. But when you set logical people the task to solve a persistent problem, you’re likely to fail. Your problem most likely is logic-proof, because if the solution was logical, you would have found it already. There will most likely be a solution, but conventional, linear rationality isn’t going to find it. These are the problems that gridlock government decision making, divide politicians, make businesses obsess. And the only reason why they are still problems is because no one has had the balls to try an irrational solution to solve them.

We need to find what has never been found before, and thus we cannot use logic.

We must have giant metaphorical balls.

12. (because why restrict yourself to a predetermined number?) Dare to look stupid

One of the ways to solve a problem is to ask a question no one has asked before. There are several reasons why a specific question hasn’t been asked before. One might be because no one was clever enough to ask it. A more likely explanation is that no one was stupid enough to ask it. There are copious amounts of questions that will make you sound incredibly dumb, and you should never hesitate to ask them. The only reason they make you sound like an idiot is because there is likely a preconceived, rational answer to that particular question. But, as has been explained thoroughly, rationality is the enemy of alchemy.

We deploy more rigour and structure to our decision-making in business because so much is at stake; but another, less optimistic, explanation is that the limitations of this approach are in fact what makes it appealing—the last thing people want when faced with a problem is a range of creative solutions, with no means of choosing between them other than their subjective judgement. It seems safer to create an artificial model that allows one logical solution and to claim that the decision was driven by ‘facts’ rather than opinion: remember that what often matters most to those making a decision in business or government is not a successful outcome, but their ability to defend their decision, whatever the outcome may be.

We need to ask questions that no one has ever asked.

We must eschew explanation and abhor justification.

V. The Rosicrucian Dream

For today’s final lesson, we need to first consider the wider cultural milieu in which Péladan was operating.

The occult mania that crested in the decades before the First World War had been intensifying throughout the nineteenth century. Its manifestations included Theosophy, Spiritism, Swedenborgianism, Mesmerism, Martinism, and Kabbalism—elaborations of arcane rituals that had been cast aside in a secular, materialist age. Reinventions or fabrications of medieval sects proliferated: the Knights Templar, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (the habitat of Yeats), and various Rosicrucian orders. Péladan belonged to the Rosicrucians, who, following sixteenth-century tracts of dubious authenticity, believed in alchemy, necromancy, and other dark arts. (“The Occult Roots of Modernism”)

It was in a such an environment that Péladan formed the Order of the Catholic Rose + Croix of the Temple and the Grail and staged the Salon de la Rose + Croix exhibitions. The notion that one could form a small sect devoted to the revival of lost magic arts and the spiritual transformation of mankind seemed entirely realistic to him because he was in fact living in the midst of such a revival and transformation. Though the full triumph would not be apparent for another century or so, it was already clear by the late 1800s that Rosicrucianism had succeeded in using “esoteric truths of the ancient past” to initiate a “universal reformation of mankind”. To understand how this was achieved, we must first do a bit of stage-setting; Wikipedia, that impenetrable citadel of truth, will serve as our guide to Rosicrucianism.

Rosicrucianism is a spiritual and cultural movement that arose in Europe in the early 17th century after the publication of several texts purported to announce the existence of a hitherto unknown esoteric order to the world and made seeking its knowledge attractive to many. The mysterious doctrine of the order is “built on esoteric truths of the ancient past”, which “concealed from the average man, provide insight into nature, the physical universe, and the spiritual realm.” The manifestos do not elaborate extensively on the matter, but clearly combine references to Kabbalah, Hermeticism, alchemy, and Christian mysticism.

The Rosicrucian manifestos heralded a “universal reformation of mankind”, through a science allegedly kept secret for decades until the intellectual climate might receive it. Controversies arose on whether they were a hoax, whether the “Order of the Rosy Cross” existed as described in the manifestos, and whether the whole thing was a metaphor disguising a movement that really existed, but in a different form. In 1616, Johann Valentin Andreae famously designated it as a “ludibrium” (a trivial game). Some scholars of esotericism suggest that this statement was later made by Andreae in order to shield himself from the wrath of the religious and political institutions of the day, which were intolerant of free speech and the idea of a “universal reformation”, for which the manifestos called.

Further background on the origins of Rosicrucianism:

Between 1614 and 1617, three anonymous manifestos were published, first in Germany and later throughout Europe. These were the Fama Fraternitatis RC (The Fame of the Brotherhood of RC, 1614), the Confessio Fraternitatis (The Confession of the Brotherhood of RC, 1615), and the Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosicross anno 1459 (1617).

The Fama Fraternitatis presents the legend of a German doctor and mystic philosopher referred to as “Father Brother C.R.C.” (later identified in a third manifesto as Christian Rosenkreuz, or “Rose-cross”). The year 1378 is presented as being the birth year of “our Christian Father”, and it is stated that he lived 106 years. After studying in the Middle East under various masters, possibly adhering to Sufism, he was unable to spread the knowledge he had acquired to prominent European scientists and philosophers. Instead, he gathered a small circle of friends/disciples and founded the Rosicrucian Order (this can be deduced to have occurred around 1407).

During Rosenkreuz’s lifetime, the order was said to comprise no more than eight members, each a doctor and “all bachelors of vowed virginity.” Each member undertook an oath to heal the sick without accepting payment, to maintain a secret fellowship, and to find a replacement for himself before he died. Three such generations had supposedly passed between c. 1500 and c. 1600: a time when scientific, philosophical, and religious freedom had grown so that the public might benefit from the Rosicrucians’ knowledge, so that they were now seeking good men.

I ask you, dear reader, did a “universal reformation of mankind” not occur? Was that not the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution? Do we not have scientific, philosophical, religious, and political freedoms that were virtually unimaginable in the Europe of 1614? Is the world today not a fantastic dream compared to that of the medieval era?

But how was it done?

The manifestos were, and continue to be, not taken literally by many but rather regarded either as hoaxes or as allegorical statements. They state: “We speak unto you by parables, but would willingly bring you to the right, simple, easy, and ingenuous exposition, understanding, declaration, and knowledge of all secrets.”

Through games (“ludibrium”) and hoaxes, through allegories and parables.

In the early 17th century, the manifestos caused excitement throughout Europe by declaring the existence of a secret brotherhood of alchemists and sages who were preparing to transform the arts and sciences, and religious, political, and intellectual landscapes of Europe. The works were re-issued several times, followed by numerous pamphlets, favorable or otherwise. Between 1614 and 1620, about 400 manuscripts and books were published which discussed the Rosicrucian documents.

By promising a spiritual transformation at a time of great turmoil, the manifestos influenced many figures to seek esoteric knowledge. Seventeenth-century occult philosophers such as Maier, Robert Fludd, and Thomas Vaughan interested themselves in the Rosicrucian world view. According to the historian David Stevenson, it was influential on Freemasonry as it was emerging in Scotland.

(more on the relationship between Rosicrucianism and Freemasonry below)

The idea of such an order, exemplified by the network of astronomers, professors, mathematicians, and natural philosophers in 16th-century Europe promoted by such men as Johannes Kepler, Georg Joachim Rheticus, John Dee and Tycho Brahe, gave rise to the Invisible College. This was the precursor to the Royal Society founded in 1660. It was constituted by a group of scientists who began to hold regular meetings to share and develop knowledge acquired by experimental investigation. Among these were Robert Boyle, who wrote: “the cornerstones of the Invisible (or as they term themselves the Philosophical) College, do now and then honour me with their company...”

Discreetly and indirectly, through inspiration and influence.

If I may briefly summarize:

Three anonymous manifestos were released which vaguely described a secretive brotherhood aimed at initiating a universal reformation of mankind and promoting freedoms of various kinds through the application of ancient esoteric knowledge. This inspired a bunch of people, including some of the greatest minds of the day, to believe that a small group of people working behind the scenes could revolutionize the world and discover hidden knowledge. This led to the formation of countless clandestine sects and societies like the Freemasons and the Invisible College which eventually catalyzed the birth of modern science and the founding of a country dedicated to the principles that Rosicrucianism espoused.

If I may summarize even more briefly:

Those madmen fucking meme’d the modern world into existence.

You may think it an exaggeration to claim that the American Revolution and the Scientific Revolution can trace their origins to Rosicrucianism, but I assure you that it is so. As noted above, Rosicrucianism was quite influential in the development of Freemasonry, which in turn was practically and philosophically instrumental in the founding of the United States.

In Freemasonry in the American Revolution, published in 1924, Sydney Morse (himself a Mason) argued that Freemasonry ‘brought together in secret and trustful conference the patriot leaders in a fight for freedom’. According to Morse, it was Masons who sank the Gaspee in 1772, who organized the Boston Tea Party, and who dominated the institutions that led the revolution, including the Continental Congress. Though repeated in the 1930s by the French historian Bernard Fay, this claim was for a long time ignored by the leading historians of the American Revolution. When Ronald E. Heaton researched the backgrounds of 24I “founding fathers”, he found that only sixty-eight had been Masons. Just eight of the fifty-six signers of the Declaration of Independence belonged to Masonic lodges. For years the mainstream view was that it was doubtful whether Freemasons qua Freemasons played a significant role in the American Revolution. But this conclusion itself seems doubtful. Apart from anything else, it assumes that all founding fathers were equal in their importance, whereas network analysis shows that Paul Revere and Joseph Warren were the most important revolutionaries in Boston, the most important city in the revolution. It also understates the importance of Freemasonry as a revolutionary ideology. The evidence suggests that it was at least as important as secular political theories or religious doctrines in animating the men who made the revolution…Freemasonry furnished the Age of Reason with a powerful mythology, an international organizational structure and an elaborate ritual calculated to bind initiates together as metaphorical brothers.

—Niall Ferguson, The Square and the Tower

(See also Rosicrucian America: How a Secret Society Influenced the Destiny of a Nation)

VI. The Alchemist’s Dream

As for modern science, it was previously noted how Rosicrucianism inspired the Invisible College which became the first scientific society, however it goes much, much deeper than that. One of the esoteric arts that the Rosicrucians purported to revive was that of alchemy, an ancient intellectual tradition which is now almost universally and completely misunderstood. Ted Chiang, one of the greatest living science fictionists (and authors, period), describes this common but flagrantly false view in his podcast appearance on The Ezra Klein Show.

EZRA KLEIN: I’ve heard you refer to the pivotal moment in the history of science as the emergence of the discipline of chemistry over that of alchemy. Why was that important?

TED CHIANG: So, one of the things that people often associate with alchemy is the attempt to transmute lead into gold. And of course, this is appealing because it seems like a way to create wealth, but for the alchemists, for a lot of Renaissance alchemists, the goal was not so much a way to create wealth as it was a kind of spiritual purification, that they were trying to transform some aspect of their soul from base to noble. And that transformation would be accompanied by some physical analog, which was transmuting lead into gold. And so, yeah, you would get gold, which is cool, but you would also have purified your soul. That was, in a lot of ways, the primary goal.

And that is an example, I think, of this general idea that the intentions or the spiritual nature of the practitioner was an essential element in chemical reactions, that you needed to be pure of heart or you needed to concentrate really hard in order for the reaction to work. And it turns out that is not true. Chemical reactions work completely independently of what the practitioner wants or feels or whether they are virtuous or malign. So, the parts of alchemy which ignored that spiritual component, those eventually became chemistry. And the parts of alchemy which relied on the spiritual components of the practitioner were all proven to be false. And so, in some ways, the transition from alchemy to chemistry is a recognition of the fundamentally impersonal nature of the universe.

Here is Jordan Peterson (sorry but you had to know I was going to quote him at least once) describing Carl Jung’s (accurate) analysis of alchemy and its relationship to the birth of science.

“The idea we have that science is a useful endeavor, that we are looking to the material world for redemption, that’s all part of a narrative. I [Jordan Peterson] was absolutely staggered by Jung’s analysis of the emergence of science out of alchemy. His notion was that the alchemical tradition was a 2,000-year-old dream, a narrative dream, a counter-position to Christianity with its emphasis on abstracted spirituality, suggesting that what we lacked could be found in the depths of the material world. And so there was this motivational dream that if we paid enough attention to the transformations of matter we could find that which would confer on us eternal life, infinite health, and infinite wealth (note: he is speaking of the concept of the philosopher’s stone, a stone which could supposedly confer all of the listed benefits, the creation of which was regarded as the central goal of alchemy). Jung’s point was that until that dream was in place there would not be motivation to undertake the process of the painstaking analysis of the material world that didn’t produce any immediate gratification and it took thousands of years for that idea to assemble itself with enough force so that we could start to have scientists.”

— Jordan Peterson, from the podcast episode “An Atheist in the Realm of Myth” with Stephen Fry

Do you see?!? Alchemy was not simply a misguided precursor to modern chemistry, it was a spiritual project which transmuted our wildest dreams into reality. The spiritual elements of alchemy were not pseudoscientific baggage but catalysts for the psychological and philosophical transformations needed to create Science, the actual philosopher’s stone through which we might one day attain eternal life and infinite wealth.

“Today’s fashionable neural networks and deep learning techniques are based on a collection of tricks, topped with a good dash of optimism, rather than systematic analysis. Modern engineers, the thinking goes, assemble their codes with the same wishful thinking and misunderstanding that the ancient alchemists had when mixing their magic potions…However, we should never forget the hard-won cautionary lessons of history. Alchemy was not only a proto-science, but also a “hyper-science” that overpromised and underdelivered. Astrological predictions were taken so seriously that life had to adapt to theory, instead of the other way around. Unfortunately, modern society is not free from such magical thinking, putting too much confidence in omnipotent algorithms, without critically questioning their logical or ethical basis.”

— Robbert Djikgraaph, “The Uselessness of Useful Knowledge”

Scientific progress has brought us full circle; the Age of Alchemy is now upon us once again. If we are to make it through this epoch and reach the next stage of cosmic evolution—if we are to turn never-ending cycle into ever-ascending spiral—then we must revive the Alchemist’s Dream and the Rosicrucian Dream and initiate a next “universal reformation of mankind”.

And so, Brothers and Sisters, I say unto you:

We must band together into small groups (fraternities, sororities, societies, sects, cults, etc.) and work in secrecy and anonymity. We must spread rumors and plot subversions. We must run irrational experiments. We must create rituals, forge symbols, make myths, and imagine messiahs (or saints). We must dare to dream the most absurd grandiose dreams. We must write vague, rambling manifestos (like this one). We must proclaim self-fulfilling prophecies.

We must meme our way to paradise.

VII. Conclusion: Announcement and Q & A

This seems like the absolutely perfect time to announce that I am forming my own secret society and/or cult. If you have read this far, then you have passed the first test—clearly you are person of tremendous fortitude, someone whom I should want on my side (email matryoshka.x11 at gmail.com to express interest in joining). Get in on the ground floor, become an apostle, become a saint—what a golden opportunity you have been presented with.

In closing, I want to address a few questions and concerns that I’m sure some of you might have.

Q: Matryoshka X, you declared that you wanted to become a world historical figure, but yet you write pseudonymously on a pseudonymous friend’s blog. Won’t this prevent you from becoming a civilization-altering colossus whos name rings out through the ages?

A: Indeed it might. After all, Christian Rosenkreuz, the mythical founder of Rosicrucianism, is not a World Historical Figure (though perhaps he should be) and neither is the author of the original manuscripts (possibly Johann Valentin Andreae, but we don’t know for sure). Still, I suspect that anonymity will be critical in my quest to initiate a mass spiritual awakening and thus I remain so.

Some of you may also be suspecting that Matryoshka X is just another pseudonym for Roger’s Bacon and that it is actually he who is writing this. I assure you that this is not the case. Roger’s Bacon may even claim at some point in the future that he is the author of this manifesto—do not listen to him, Roger’s Bacon is a liar and a scoundrel. He is also a dullard and a simpleton who is wholly incapable of writing with the skill and artistry that has been displayed in this essay.

Q: I’m a little uneasy with your declared ambition to become a World Historical Figure. Don’t you think it’s a little narcissistic and egotistical of you?

A: Indeed it is and that’s the whole point.

We need characters in novels to be free to range into the dark and wrong. How else will we understand ourselves?” (Ottessa Moshfegh)

If, as they say, the road to hell is paved with good intentions, then ipso facto the road to heaven must be paved with bad intentions, with greed, selfishness, vanity, hubris, and delusions of grandeur. For all of human history, these qualities have been maligned, and yet no progress—absolutely none—has been made in their amelioration. If we truly wish to stop the serpent from biting its tail, to transcend the flat circle of time and transform the human spirit, then we must not run away from the Darkness—we must go through it.

Q: But Matryoshka X, what if you fail?

A: Of course I will fail, but my hope is to fail spectacularly, beautifully. Perhaps one day I will become a footnote in the wikipedia page of the next World Historical Figure, or even better, maybe someone will write “How to Become a World Historical Figure Part 2 (Matryoshka X’s Dream)”.

What the flying fuck is this

what don’t you understand, seems pretty clear to me