I’m so frustrated by low-decoupling academics who refuse to acknowledge basic evaluative facts (like that, all else equal, it’s better to have smarter, healthier children) because they’re terrified of what they—mistakenly!—imagine to be the implications. If they’d just stop and think clearly for a minute, it shouldn’t be that hard to appreciate why the feared implications don’t really follow. (Hint: we should reject naive instrumentalism.)

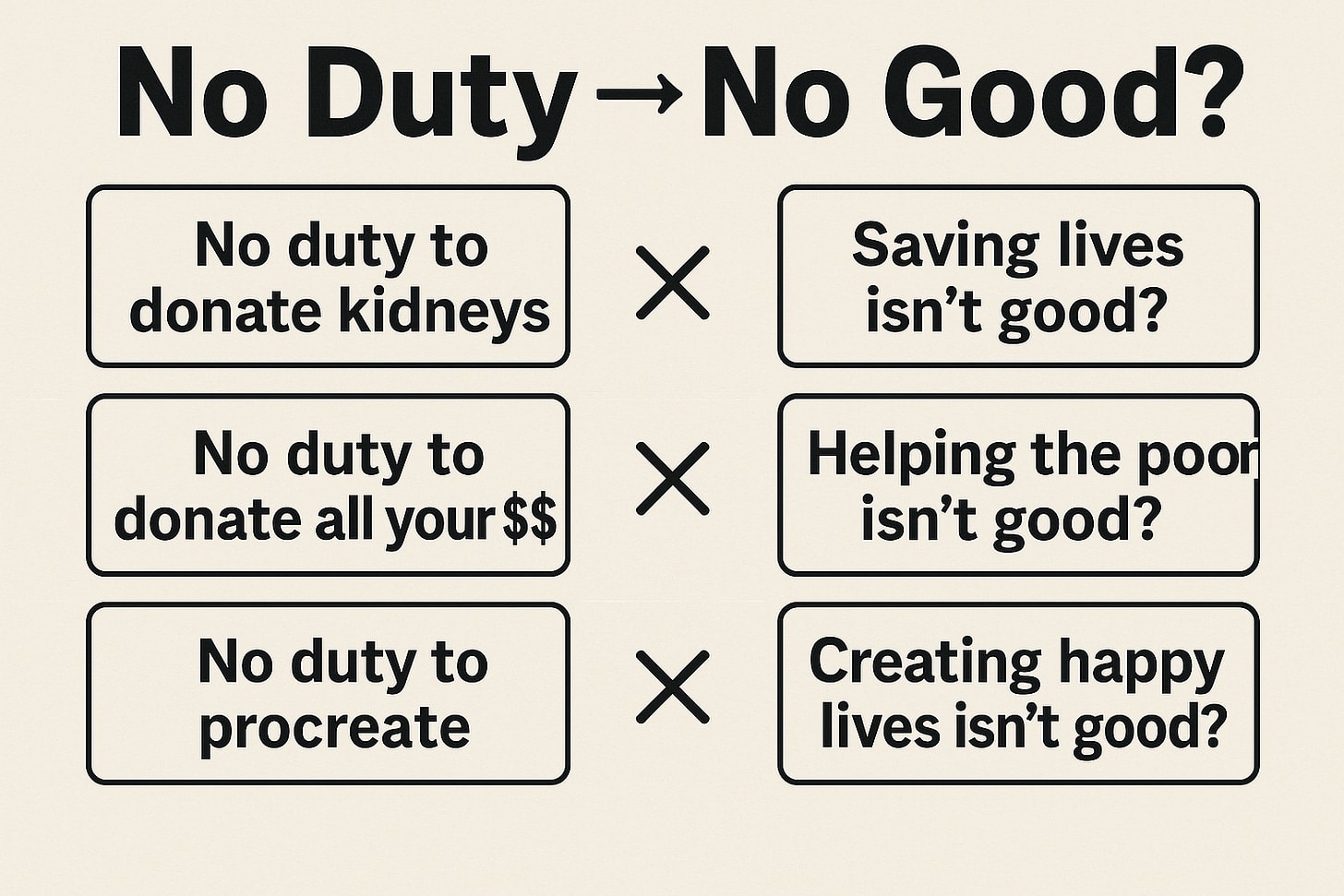

I’m especially shocked by how many fall for (what we might call) the “No Duty → No Good” fallacy. As far as I can tell, the error is limited to reproductive ethics: I’ve never heard people reason so badly about other topics. But whatever the explanation, it’s incredibly common for (even otherwise intelligent) people to affirm the following bad argument: “It can’t be good to create happy lives, because that would generate implausible procreative duties: we would all be obligated to have as many kids as possible.”[1] Since there’s no such duty, they reason, there can’t be anything good about the act in question.

Imagine reasoning like this about other topics. “It can’t be good to save the lives of dialysis patients, because that would generate implausible duties of kidney donation.” Or “children dying of malaria must not matter, lest they generate implausible duties of beneficence to donate all our money to effective charities.”

It’s especially odd for non-consequentialists, of all people, to presuppose an obligation to maximize the impartial good. As I explain in ‘Rethinking the Asymmetry’:

If we think that we are not obligated to do certain things in order to benefit others, we should not conclude that those “others” do not matter. A more promising strategy is to focus on the “certain things” being requested of us, to see whether they might be too much to ask in a way that would explain the lack of obligation. Commonsense morality rejects the idea that we have to sacrifice everything to help the global poor, not because the global poor don’t matter, but because our sacrificing everything does matter, and would be too much for morality to demand of us.

And so it goes, I suggest, for the commonsense rejection of positive procreative duties. In our biological, psychological, and cultural context, to require procreation would be massively intrusive and demanding. (Pregnancy alone is arguably more demanding than, say, giving up a kidney would be. And that’s before we even consider the life-changing implications of either raising a child or giving up one’s progeny for adoption. Or, for that matter, the idea that people have a moral prerogative, not easily overridden, over their genetic material.) If extreme financial duties of beneficence are too demanding to countenance, surely positive procreative duties are all the more so. So there’s no motivation here to deny [that it’s good to add happy lives to the world]. Implausible procreative obligations are better denied on grounds of their excessive demandingness. It’s not that possible people don’t matter, but just that actual people (who would have to bear and rear them) do.

So, please remember: just because you’re not intuitively obliged to do something, it doesn’t follow that there’s nothing good about the act in question. Commonsense morality allows good things to be supererogatory—“above and beyond” the call of duty! And even utilitarianism plausibly supports liberal rights:

Obviously, there is a huge gap between “X is good” and “People should be forced to promote X, no matter the costs.” Unless you are deeply illiberal, you should not, in general, have any fear that recognizing something as good will somehow make this gap disappear. (And you shouldn’t be deeply illiberal!)

For more on why we should think it good to create happy lives, see:

The Profoundest Error in Population Ethics- ^

A recent example can be found in Alex McLaughlin’s ‘Visionaries and Crackpots, Maniacs and Saints: Existential Risk and the Politics of Longtermism’: “Rejecting the intuition of neutrality comes with costs. It seems to entail a moralism about procreative choice that is in tension with basic feminist commitments, for example…”In ‘Rethinking the Asymmetry’, I cite Christian Piller’s reasoning in ‘What is Goodness Good For?’: “saying that more lives are better than fewer lives… offends the deeply held asymmetry of our attitudes to creation and destruction of human life: destruction is forbidden; creation is not obligatory.”

Hi Richard,

I’m your first and only example of a ‘low-decoupling academic’. You mischaracterise my view though. I don’t think longtermism implies we have duties ‘to have as many kids as possible’, nor do I say that in the paper. What I say, as you make clear in your footnote, is that longtermism ‘seems to entail a moralism about procreative choice that is in tension with basic feminist commitments’. Those two claims are quite different.

To moralise about something, in the pejorative sense, is (roughly) to subject a decision or domain to moral evaluation in a way that is inappropriate or out of place. By rejecting the intuition of neutrality, longtermists seem to believe there is a prior moral reason, independent of the circumstances, preferences and plans of those considering procreation, which bears on the decision about whether to have a child. I suspect—though note the offending sentence is an aside in the paper and not central to any of the arguments—that feminists will think the decision about whether to procreate is not one which should be subject to moral evaluation in this way. That might be wrong about what feminists think, or otherwise implausible as a view about procreative choice, but it’s not a claim about a putative duty to procreate.

It’s at least good to see that someone has read my paper!

Hi Alex, thanks for clarifying what you had in mind. I very commonly hear people raising the worry about procreative duties (I give another, more explicit example in the very same footnote), so it seemed most natural to interpret you as gesturing at that common concern, but I apologize if I got that wrong.

Your suggested weaker reading is a bit puzzling though, since even if many feminists happen to think that procreative decisions are not “subject to moral evaluation” even in the weakest sense, that doesn’t seem to be a basic commitment of feminism in the way that, say, being pro-choice about abortion and procreative duties is. Surely someone could (easily!) be a feminist in good standing—accepting all the basic commitments of the view—while thinking that one always has some reason to choose to create a good life (while nonetheless retaining bodily rights and prerogatives to decide otherwise).

(I agree that none of this is central to your paper.)

Edited to add: I didn’t intend to give any named examples of “low-decoupling academics”—that would be rather rude! The footnote is rather supporting my claim that “it’s incredibly common for (even otherwise intelligent) people to affirm the following bad argument...”

More substantively: I think there’s still a “no moralism → no good” fallacy even on the weaker interpretation. If you think it’s a “cost” or “inappropriate” to “subject a decision or domain to moral evaluation,” then it seems like you must have more in mind by “moral evaluation” (perhaps some susceptibility to external blame or criticism) than just recognizing that one choice may do more good than another (in a way that gives the agent some reason to make that choice). For example, presumably we shouldn’t “moralize” someone’s decision about whether to keep their kidneys. But it’s still clearly good to save the lives of dialysis patients.

Hi Richard,

Thanks for responding and clarifying. You might be right that I overstate the point when I describe the commitment as ‘basic’, at least in the sense that an opposition to this particular claim in population ethics is not central to feminist writing or activism. But given the role moralised views about procreation have played in the subordination of women, there does seem to be a tension between this feature of longtermism and feminism as a political project, and that’s what I was trying to get at.

I’m still worried about the moralism of longtermism here, even in light of the fallacy you formulate against my weaker claim. This isn’t necessarily because I think longtermists will subject individuals to criticism for their choices. It’s more because I understand longtermism as a view about our ‘collective priorities’ which is supposed to have a range of practical upshots. If rejecting the intuition of neutrality is central to that project, then it’s hard to see how it can avoid a moralism about procreation. Longtermists should want people to think and act as if having kids is a morally good thing to do, and MacAskill, as I recall anyway, is pretty open about this.

(Note there’s plenty more to say about moralism than I say in my previous comment and, as I suggested before, about all of this than I say in that passage of the paper.)

I hope this does something to clarify!

Oh, I absolutely agree that we “should want people to think and act as if having kids is a morally good thing to do.” Just as we should think of kidney donation, of adoption, of all sorts of very personal decisions that should be 100% up to individuals to decide for themselves, even though they are good things to do! The question is what further (if anything) follows that is concerning about any of this, such as to warrant the pejorative term “moralism”.

I don’t think a historical correlation between accepting a true evaluative fact and responding badly and wrongly to it is good grounds for rejecting the true claim. (That’s actually precisely the pattern of practical reasoning that I take to be constitutive of “low decoupling”.) We should instead reject the supplemental “naive instrumentalist” assumptions that led people to respond badly and wrongly to the evaluative truth in question.

Again, I’m worried—and I think people with feminist commitments in general will be worried – about an influential view about our collective priorities which inculcates in people the belief that people can do something morally good by having kids. That’s a concern about the politics of longtermism, which I characterise (in passing!) in terms of moralising procreative choice. Longtermists clearly don’t share this concern, nor do you.

I don’t take a view on the “evaluative fact” of whether the intuition of neutrality is correct; rather, my general argument in the paper is that longtermists have been unwilling to engage with political thought and as a result arrive at political positions that are both ambiguous and unattractive. Your original post and subsequent comments seem illustrative in this regard. Attempting to construe some disagreement about longtermism in terms of a simple logical fallacy serves, in my view, to conceal lots of the detail relevant to criticisms of the view, as I have alluded to in my responses. Likewise, to disparagingly characterise positions as ‘low-decoupling’ looks like asserting the abstract and impartial perspective as the authority for making claims about the social world, which is precisely what is at stake in debates between longtermism and its critics.

Probably we should leave it here, although feel free to send me your future writing on the topic, as I’d be interested in taking a look.

Thanks for the exchange. I absolutely do endorse taking “the abstract and impartial perspective” as authoritative for assessing public policy and related social issues. (The alternative strikes me as simply indulging in uncritical vibes and bias.)

For my future reference, is there an alternative (less derogatory or stigmatizing) label you’d recommend that I use in place of “low decoupling” to pick out your alternative approach to normative assessment? It strikes me as an incredibly important methodological disagreement, and it’s useful to have names for different positions.

It is certainly an important disagreement. There are loads of literatures in political theory that aim to shed light on the way different political problems and practical contexts might properly shape our normative conclusions. Longtermists seem to ignore those debates, which might be fine if their view wasn’t, as I try and show in the paper, deeply political.

Views that take seriously political concepts, constraints and contexts do not indulge in ‘uncritical vibes and bias’. It’s partly effective altruism’s tendency to ignore questions about politics—for example, about power, democracy and the processes which produce social deprivation—that make it a fundamentally conservative movement, as many critics have pointed out.

I’m not sure whether I fully understand what ‘low decoupling’ is, as I came across the idea for the first time in your post and have looked at it only briefly. But yeah, I don’t think it will be a useful concept around which to locate disagreements between longtermists and critics, although that will depend on the specifics. I’m not sure there is a straightforward term that will carve up the field. The safest approach is to engage with the substantive details of particular arguments—that’s what I at least try to do in the paper!

Would you like to suggest a recommended reading that best advances your general perspective here while seriously addressing the charge of uncritical vibes and bias?

From my perspective, it seems like you’re just flatly ignoring my concerns (simply asserting that you “do not indulge in ‘uncritical vibes and bias’” doesn’t allay my concerns, any more than my simply asserting, without further explanation, that impartial moral theorists of my ilk do not ignore questions about power, democracy, etc., would allay yours). One reason I’m inclined to ignore certain academic literatures is that the participants in those literatures seem to take for granted certain misguided foundational assumptions that I take to undermine their entire enterprise. Given my starting perspective, it’s not clear why I should expect to learn anything from reading people who strike me as deeply confused and don’t say anything that addresses my fundamental concerns about their approach.

I would like to see more productive engagement between the two perspectives. But that requires both sides to make some effort to understand and address the other’s concerns.

(I may write more about the substance of your paper at some point, but something that annoyed me a lot when reading it was that you largely seemed to be uncritically laundering the complaints of public critics like Emile Torres, without any apparent understanding of—and engagement with—why longtermists disagree. The suggestion that our approach is “fundamentally conservative” strikes me as particularly groundless, and indicative of unprincipled, vibes-based criticism. But if nothing else, I guess it’s at least helpful to have the criticisms collated in one place, and maybe if I take a stab at addressing them at some point that would be a step towards more mutual engagement. You may also be interested in the final section of my paper, ‘Why Not Effective Altruism?’ where I respond to the “political” critiques of Srinivasan and others.)

I thought this was a great post, thanks for sharing! I think you’re unusually productive at identifying important insights in ethics and philosophy, please keep it up!

I think the problem is your argument wasn’t for “happy” children, it was for “smart and healthy” children. And that’s where it sounds a bit eugenicist.

What if being particularly intelligent makes people less happy? The evidence is mixed, but I rather suspect there are many EAs who wouldn’t necessarily see their intelligence as a source of happiness, but neither would they choose to give it up.

And with health, the same challenge applies. Neurodivergence is probably over-represented amongst EAs, but I don’t think many people are saying it shouldn’t exist.

I believe that genetic and phenotype diversity is beneficial to any population. And from a human perspective, I believe differences of experience are culturally and morally valuable—in that they force us to expand our empathy to others who are not like us. Activity that has the effect of limiting that diversity, and entrenching economic inequality, has the potential to have net negative impacts on humanity, even if there are benefits at the individual level.

Funny how people never raise this as an argument against preventing lead poisoning.

Here’s a parity principle I think we should all accept: if we would encourage prospective parents to undertake environmental precautions or modifications to shift the balance of probabilities for their future child in a certain way, we should encourage them to pursue the same ends via genetic means.

I don’t assume that every form of “divergence” from “typical” functioning is necessarily a disability or health problem. There will always be unclear or controversial cases about which reasonable people can disagree. But there are also very clear cases, like Tay-Sachs disease, which we should obviously want to prevent if we can (including via embryonic selection or gene editing).

Agreed on Tay-Sachs and other diseases which cause suffering.

That’s not the same as gene-editing and embryo selection for “smarter” kids. That’s making a moral judgement about the value of someone’s life based on their intelligence. By your logic, if we tell people not to drink alcohol when pregnant, then we should also prevent those with lower intelligence from passing on their genes?

No, I support genetic reproductive freedom, not coercion. This is all a bit off-topic here though, so perhaps you can follow-up over at the linked post if you want to discuss this more.

Executive summary: The author critiques what they call the “No Duty → No Good” fallacy in reproductive ethics, arguing that the absence of moral obligation to create happy lives doesn’t mean there’s nothing good about doing so—a mistaken inference that reflects deeper confusion about the relationship between moral value and duty.

Key points:

Many people wrongly infer that if creating happy lives would imply problematic moral duties (e.g., being obligated to have many children), then it must not be good to do so—this is the “No Duty → No Good” fallacy.

Analogous reasoning in other domains (like saving lives or helping the poor) would be clearly absurd, suggesting the fallacy arises from inconsistent standards applied to reproduction.

The better explanation for rejecting procreative obligations is their excessive demandingness, not a denial of the moral value of happy lives.

The author emphasizes the importance of distinguishing between something being good and being morally required; many good actions are supererogatory rather than obligatory.

This fallacy is particularly puzzling when committed by non-consequentialists, who shouldn’t presuppose a requirement to maximize the good.

Recognizing the value of creating happy lives does not threaten liberal commitments or imply coercive policies, so fears of such consequences are unfounded.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.