When in doubt, apply*

Cross posted to my blog

I hope this post:

Provides useful tips on how to handle the process of applying, especially to EA jobs and grants, so that it is more rewarding, less stressful and helps you find a that is a good personal fit for you. I hope this post can help you avoid becoming bycatch,

Encourages you to apply to more jobs and grants (not just EA ones), and apply more widely.

“EA jobs” refers to jobs posted by organisations that are explicitly EA-aligned, similarly for “EA grantmakers”.

*A few quick caveats

Giving advice is hard. I write this post from my personal experience and observations and have shared it with multiple people working at EA organisations for review. I’ve added additional notes on sections I’m more uncertain about. I also hope the following caveats can help you determine if this advice applies to you. I encourage you to explore the relevant tags, ask questions and make sure this advice is relevant to your cause area or domain.

I assume you’ve spent time reflecting on your options and determined that applying to new opportunities in the EA space is the right step for you at this time. If you haven’t, this is far from the only option. You can explore EA ideas and opportunities more slowly while doing non-EA things—for example, by getting involved in your local community, testing out projects, skilling up or attending events. I think this is probably the right step for most people, especially people newer to the EA movement.

Don’t apply to (EA) jobs you don’t have a genuine interest in, or that you don’t think there’s at least a small chance (>25%) you’d actually take it

If you followed 2), don’t worry about wasting an organisation’s time or money evaluating your application. If they proceed with your application, trust that they have done the cost-benefit calculations already and decided it’s worth it. If you make it to the final stages, and think it’s still very unlikely you’d accept, it can be moderately costly for an organisation to make an offer as it can add delays to hiring runner-up applicants. That doesn’t mean you should pull out. Instead, explain your current options and thinking to the organisation and ask questions to help you make sure you’re making the right decision.[1] It’s good to think critically.For example, you could ask about your counterfactual impact in this role (e.g.“What would you do if I declined the offer?”). I Sometimes, the organisation may not have a second candidate in mind and not end up hiring for the role at all. This would be important information to factor into your decision.

Job applications...

are a cheap test to evaluate personal fit

Compared to normal jobs, EA job applications often have multiple rounds of work tests which can be excellent opportunities to test your personal fit for a role. For example, if you apply for a grantmaking organisation the work test might be to evaluate a sample grant. It’s a great way to get a more realistic view of what the work is like.

Some EA-aligned organisations will also give you feedback on your work tests (more so in later stages), which can also be useful for improving your skills.

can teach you things

You can learn about the kind of work an organisation does on the ground, the kinds of skills they value, and even develop those skills as you do more and more tests.[2] I have found test tasks that require me to practice specific skills such as reasoning transparency or summarising information clearly and concisely especially valuable. Practising these skills in a situation with meaningful stakes but which I didn’t find too stressful also helped me internalise these skills more than otherwise.

can often be be fun

This may be an unpopular opinion, but I (and 2 of my reviewers) think some work tests can actually be quite fun. I find that applying the EA frameworks or thinking to practical examples can be really engaging, invigorating and rewarding. A test task involving intervention evaluation for a research intern position at Charity Entrepreneurship was really fun because it was very representative of the actual work I’d do in the internship. It was really motivating to actually be able to put the theory into practice. (I’d read up a lot on CE’s research process out of curiosity, so I was maybe even more excited than someone with less background on the topic).

To do this, I think you need to have the right approach by not getting too attached to a specific role or organisation. If you’ve got your Plan Z and sufficient backup options (i.e. you’re applying to many positions), then hopefully each individual application will be less stressful.

Of course, some application rounds can be stressful (I’ve done some EA work tests that are >3 hours in one sitting, which is pretty mentally taxing) or if you have to do a lot of preparation for the interview.

Regarding grants…

The thoughts below come from discussions with a handful of grantmakers, grantees, online discussions from grantmakers and my own experience. (Also, here’s a list of places you can apply to!)

It’s okay to ask for money

Some people are a bit hesitant to ask for money, even when they are qualified. There are some cultural norms that make people generally squicky around money, but it may also feel counterintuitive in a movement which emphasises particularly careful use of our dollars, and whether you are “worth” the grant you are asking for. But, that’s why grantmakers can take some of the hard work of evaluating this off your chest!

Usually, there’s flexibility in how the money is used. Money is useful and your time is valuable. If a lack of money is a major (or even a minor) blocker in your life stopping you from doing important work (e.g. to pay for medical expenses or save time on daily tasks like cooking) then there’s a strong case to at least try for funding.

EA grantmakers don’t bite, so ask questions

If you think you might be rejected for some reason (e.g. technicalities or having projects that you think grantmakers aren’t interested in funding) you should probably double check your assumptions are right by emailing the grantmaker in question to clarify.

One grantee I spoke to said they thought for many months that they weren’t eligible for grants for various reasons before speaking with someone and realising they were. What’s more, you can use your application to start a dialogue with EA funders.

Orienting yourself to the hunt

There are many other articles which cover very useful & practical job hunting tips in detail (example, example, example, example). Here I want to focus on having a useful framing for how you approach a job hunt that might help keep you motivated in the face of rejection.

Build an environment to help you handle rejection

Rejections from EA-aligned opportunities can be harder to tackle than other opportunities because these opportunities provide social and career benefits and getting rejected from your in-group feels more personal. There is also a lot of competition for certain (high status, exciting, “sexy”) EA-aligned opportunities[3], making the chance of rejection higher (and some people may have the wrong expectations around the level of competition).

I think it’s important to create a sustainable environment for yourself that allows you to fail, but still stay motivated and bounce back. What that looks like depends on you—you might need to experiment to find out.

For me (I’ve been rejected from at least ~10 EA job applications and grants, and ~100 non-EA jobs), it’s been all the usual advice: I have back-up plans—both several career options and projects that I’m exploring, I can switch to high gear but also switch back down to a lower gear on projects if needed, I can accept that things were a mistake (and try to build models of why so I don’t make the same mistakes again), I have a close group of friends that I can talk to about my rejections (relatedly: you could consider celebrating rejection.)

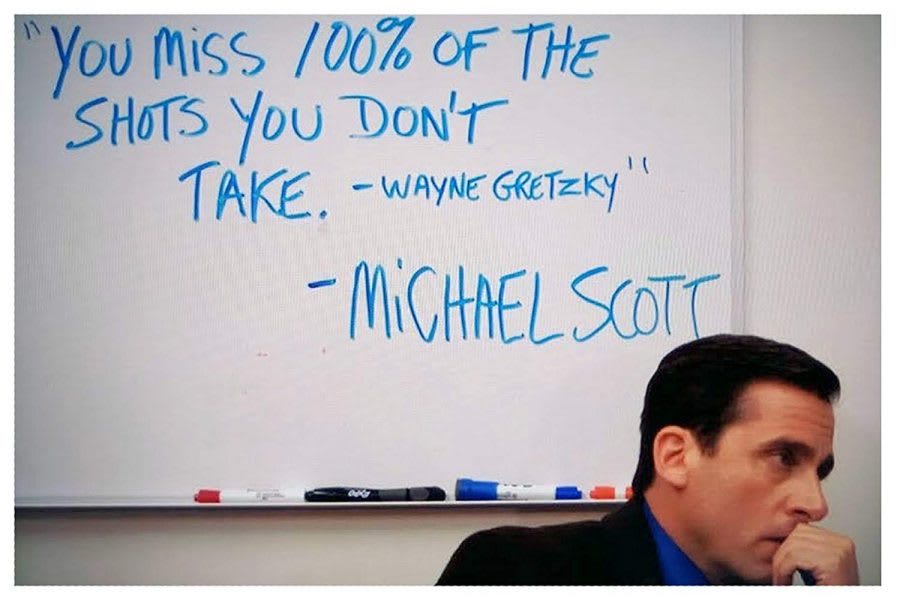

Get comfortable with rejection: Just apply!

Jobs: It’s better to apply for a job you care about with an imperfect application than not to apply at all. You can iterate & improve your application over time. Every time you apply for a new position, you can take a few minutes to tweak and improve your resume or cover letter, or perhaps answer the screening questions better, so that by the time you apply to your top jobs you feel confident in your abilities.

If you’re worried about rejection, the standard (and solid!) advice is to set up one or more backup plans. These can give you the peace of mind to take risks.

If you’re still having trouble getting even one application out the door, a little exposure therapy can help get over a fear of rejection. Find a friend, focusmate or therapist to kick you in the butt and just apply to any job you think you have a shot at getting—maybe a local tutoring gig or the first job that pops up on your LinkedIn feed. Use the application deadline as a motivator to submit something, even if it’s not amazing. The goal here is to get comfortable with applying, but importantly you don’t want to anchor yourself to these jobs.

Grants: Past rejections don’t mean you will never be funded. (EA) grantmakers can encourage people to refine their ideas and reapply, or to apply with different ideas. A rejection for a specific proposal doesn’t mean that you won’t get funding.

Don’t get too attached: Limit how much time you spend on a single application

It’s very tempting to polish and perfect an application, cover letter, or work test or practice hours for an interview, but there are many reasons to limit the time you spend per job:

Applying is a numbers game. The more time you spend on any one application will reduce the time you spend applying to other positions. This is a pretty big opportunity cost.

Spending more time on individual applications can make you more invested in each individual job, which makes rejection harder and more demotivating

If you have to spend too much time optimising for a single application, this may be evidence that you are currently not a great fit for the role. Employers have some assumptions on the distribution of effort that goes into an application. On one hand, being an outlier might indicate that you’re motivated about the job, but on the other hand it could also mean that you, your employer, or both overestimate your fit for the role. Being a bad fit can lead to burnout (on your end) and underperformance (on the impact end).

At later stages of the application process such as for the interviews, there will be some roles for which you might want to prepare more for (such as those you have a personal connection at, or your top options). But there are greatly diminishing returns to doing this too often.

Some thoughts on spending time at specific stages in the application process:

Initial job applications: I would make a one-time investment in building a solid resume/CV/cover letter that can be reused and tweaked across applications (e.g. de-emphasising less relevant experiences, see this example).

Many recruiters at small companies or orgs with relatively small hiring pools (such as many EA orgs) are looking to eliminate people who are clearly bad fits for the role, rather than trying to select the superstars. So for a first round, you just need to make sure you are passing their minimum bar.

Work tests: If you’re given a work test that abides by an honour system, you shouldn’t spend significantly more (>5-10%) of the allotted time. If you go over time, be honest. Let the recruiter know how much you went over by, and what you spent the extra time doing. (If you’re spending a bunch of time polishing this is usually not required—most organisations are okay with short/bulleted answers—they know you have limited time and everyone is facing the same constraints! Occasionally hiring managers may not put much thought into the time limit so it’s possible it was tight.[4])

Not letting them know is instrumentally bad for the community’s ability to coordinate, and, as mentioned above, can distort your/the recruiter’s ability to evaluate your fit for the role.

Spending more than that is a sign that this work may not be a good fit for you and its worth considering why it’s taking you so long to complete the test. This isn’t to say it’s definitely a sign you’d be a bad fit—some people are just not good at timed work tests—but it can be a fairly good signal!

Ultimately you want to give the employer an accurate sense of your abilities. When Linch at Rethink Priorities does test tasks he spends “<67% [of the time allotted for the work trial] because I’m psychologically capable of working less hours than most people, … and I want to give future employers an accurate assessment of my scale-appropriate actual work output.” [5]

Grant applications: For most EA grant applications, “the application can be a “dialogue”: you can apply without a 100% fleshed out idea or 100% explained reasoning, and just explicitly flag that and say you’re happy to elaborate on things but that you wanted to get the application process started because it’s time-sensitive.” [6]

You can also share your application with a mentor or friend to get their feedback, or find reviewers on the EA Editing and Review Facebook group. Here is some practical advice on making applications to the EA funds. I think many of the points can generalise to other EA grantmakers.

For non-EA grants, the above suggestions are generally not applicable. Many non-EA grants can have the opposite process with less back-and-forth. For those grants, it’s probably useful to talk to people who have experience applying to them and get advice on the best approach.

Thanks in to Michael Aird, Linch Zhang, Marisa Jurczyk and Arjun Khandelwal and a few other Rethink Priorities staff (by some coincidence) for feedback on this post. Mistakes are my own.

Changelog (01.24.2021): I’ve linked off to some cool articles that were published very soon after I published this post. I may do this periodically.

Notes

- ↩︎

H/T Marisa Jurcyzk

- ↩︎

It can even help you produce good content—one of my reviewers published modified versions of two of their work tests!

- ↩︎

There have been a few questions about competitiveness or talent gaps in the EA movement as a whole—and there isn’t one general answer on this that is valid across cause areas and domains. The variance in competition/the bar for candidates is very high. It seems positively correlated with how interesting the job seems, the status of the organisation and/or employers, job location and how much seniority/expertise/autonomy is required.

- ↩︎

One of my reviewers set the time limit for a test task by doubling the time they themselves took to complete the task themselves, while other hiring managers might ask people to test the task out beforehand.

- ↩︎

H/T Michael Aird

- ↩︎

- Don’t think, just apply! (usually) by (12 Apr 2022 8:06 UTC; 154 points)

- Advice for early-career people seeking jobs in EA by (20 Jun 2024 14:44 UTC; 134 points)

- Every Forum Post on EA Career Choice & Job Search by (31 Oct 2025 20:23 UTC; 121 points)

- Who wants to be hired? (May-September 2022) by (27 May 2022 9:49 UTC; 118 points)

- You should consider applying to PhDs (soon!) by (LessWrong; 29 Nov 2024 20:33 UTC; 115 points)

- Advice I’ve Found Helpful as I Apply to EA Jobs by (23 Jan 2022 18:53 UTC; 94 points)

- The BEAHR: Dust off your CVs for the Big EA Hiring Round! by (24 Mar 2022 8:56 UTC; 74 points)

- Who wants to be hired? (Feb-May 2024) by (31 Jan 2024 11:01 UTC; 62 points)

- Apply to fall policy internships (we can help) by (2 Jul 2023 21:37 UTC; 57 points)

- Benefits of being rejected from CEA’s Online team by (3 Jul 2023 16:34 UTC; 55 points)

- What are some artworks relevant to EA? by (17 Jan 2022 1:54 UTC; 51 points)

- EA Updates for February 2022 by (28 Jan 2022 11:33 UTC; 28 points)

- Apply to Spring 2024 policy internships (we can help) by (4 Oct 2023 14:45 UTC; 26 points)

- The 7 Types Of Advice (And 3 Common Failure Modes) by (LessWrong; 30 Dec 2025 21:55 UTC; 26 points)

- EA’s in IT (Information Technology) by (18 Feb 2023 20:17 UTC; 5 points)

I am feeling motivated after reading this. Thanks Vaidehi for writing such a piece. Hoping to come back here and write what I could achieve.

I’m glad! What kinds of roles are you applying for?

OMG what an amazing title, may I strong-upvote before even reading? <3

Update:

What??

Ok I’ll just read it

Haha I felt the title might be lacking some nuance and compensated the * but I’m glad you like the title!

This was a super motivating post. I saved many bits & pieces in a separate google keep note to look back on as I apply. I especially needed to hear the stuff about getting less attached to each application and needing to have a numbers-game mindset. Thank you for writing such a great piece!

Incredible job on the post! You really condensed all that useful info. I took notes in a separate document. 👏👏👏🎉

Also, when you said

Did you mean >25% that you’d take the job or >25% that you’d get the job?

I know it says, but I just want to be sure

Thank you! >25% that you’d take the job.