AI-based disinformation is probably not a major threat to democracy

[Note: this essay was originally posted to my website, https://www.conspicuouscognition.com/p/ai-based-disinformation-is-probably. A few people contacted me to suggest that I also post it here in case of interest].

Many people are worried that the use of artificial intelligence in generating or transmitting disinformation poses a serious threat to democracies. For example, the Future of Life Institute’s 2023 Open Letter demanding a six-month ban on AI development asks: “Should we let machines flood our information channels with propaganda and untruth?” The question reflects a general concern that has been highly influential among journalists, experts, and policy makers. Here is just a small sample of headlines from major media outlets:

More generally, amidst the current excitement about AI, there is a popular demand for commentators and experts who can speak eloquently about the dangers it poses. Audiences love narratives about threats, especially when linked to fancy new technologies. However, most commentators don’t want to go full Eliezer Yudkowsky and claim that super-intelligent AI will kill us all. So they settle for what they think is a more reasonable position, one that aligns better with the prevailing sensibility and worldview of the liberal commentariat: AI will greatly exacerbate the problem of online disinformation, which—as every educated person knows—is one of the great scourges of our time.

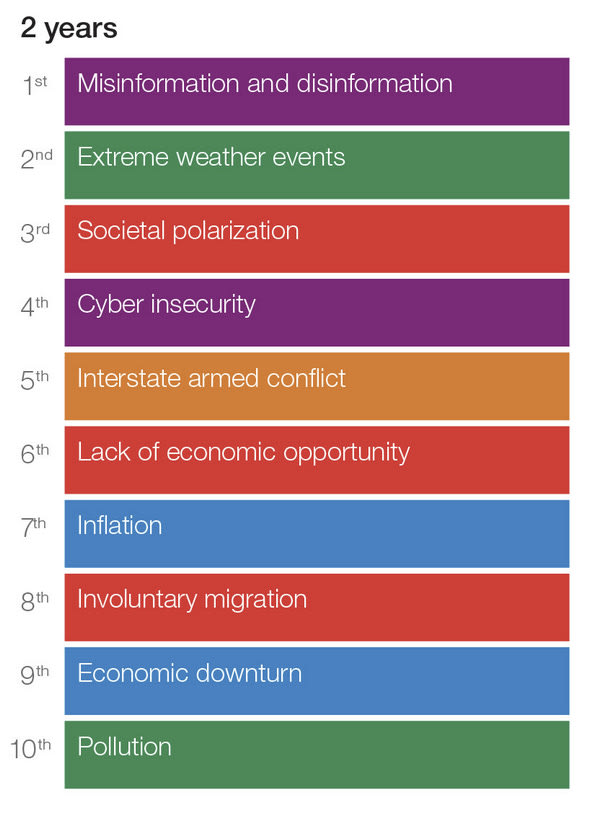

For example, in the World Economic Forum’s 2024 Global Risks Report surveying 1500 experts and policy makers, they list “misinformation and disinformation” as the top global risk over the next two years:

In defence of this assessment, a post on the World Economic Forum’s website notes:

“The growing concern about misinformation and disinformation is in large part driven by the potential for AI, in the hands of bad actors, to flood global information systems with false narratives.”

This idea gets spelled out in different ways, but most conversations focus on the following threats:

Deepfakes (realistic but fake images, videos, and audio generated by AI) will either trick people into believing falsehoods or cause them to distrust all recordings on the grounds they might be deepfakes.

Propagandists will use generative AI to create hyper-persuasive arguments for false views (e.g. “the election was stolen”).

AI will enable automated disinformation campaigns. Propagandists will use effective AI bots instead of staffing their troll farms with human, all-too-human workers.

AI will enable highly targeted, personalised disinformation campaigns (“micro-targeting”).

How worried should we be about threats like these? As I return to at the end of this essay, there are genuine dangers when it comes to the effects of AI on our informational ecosystem. Moreover, as with any new technology, it is good to think pro-actively about risks, and it would be silly to claim that worries about AI-based disinformation lack any foundation at all. Nevertheless, at least when it comes to Western democracies, the alarmism surrounding this topic generally rests on popular but mistaken beliefs about human psychology, democracy, and disinformation.

In this post, I will identify four facts that many commentators on this topic neglect. Taken collectively, they imply that many concerns about the effects of AI-based disinformation on democracies are greatly overstated.

Online disinformation does not lie at the root of modern political problems.

Political persuasion is extremely difficult.

The media environment is highly competitive and demand-driven.

The establishment will have access to more powerful forms of AI than counter-establishment sources.

1. Online disinformation does not lie at the root of modern political problems

Since 2016, a highly influential narrative posits that disinformation—especially online disinformation transmitted via social media—is a root cause of many political problems in Western democracies, including widespread support for right-wing populist movements, falling trust in institutions, rejection of public health advice, and so on. The narrative shifts around a bit, as does the emphasis on different villains (Russian disinformation campaigns, fake news, Cambridge Analytica, “The Algorithm”, online conspiracy theories, filter bubbles, etc.). Nevertheless, the core narrative that online disinformation is driving many political problems is constantly affirmed by experts, social scientists, policy makers, journalists, Netflix documentaries, and more.

When many people think about AI-based disinformation, I think this narrative is swirling around in their consciousness. They think something like: “Online disinformation is ruining democracies. AI will exacerbate the problem of online disinformation. Therefore AI-based disinformation is really bad.” Given this, the first step on the way to thinking clearly about AI-based disinformation is to recognise that this narrative is wrong. Online disinformation does not lie at the root of the problems that the liberal establishment in Western countries is most worried about.

First, despite a moral panic over social media, fake news, and online conspiracy theories, there is no systematic evidence that false claims or misperceptions are more prevalent now than in the past. In fact, evidence suggests that rates of things like conspiracy theorising have not increased and that in some areas democratic citizens are better informed.

Second, in Western democracies, exposure to online disinformation (even on very liberal definitions) is quite low on average. If people bother to follow the news at all—and many don’t—the overwhelming majority tune into mainstream media.

Third, the minority of very active social media users that do engage with lots of extremist, conspiratorial, or deceptive online content is not a cross-section of the population. They are people with very specific traits and identities—for example, highly conspiratorial mentalities, extremist political attitudes, and so on—and the media they consume mostly just seems to affirm and reinforce their pre-existing identities and worldviews.

This is a general pattern. Online disinformation is relatively rare and largely preaches to the choir. Ultimately, the reason why certain people accept it and often seek it out is because they distrust and often despise establishment institutions, elites, or their political enemies. The reasons for such feelings are complex, but exposure to online disinformation seems to play a relatively minor role.

This does not mean democratic citizens are well-informed or make good political decisions. Nevertheless, the idea that voters are only ignorant, misinformed, and make bad political decisions because they have been duped by sinister elites, interest groups, propaganda campaigns, and online conspiracy theorists is one of the great myths of our time. As Dietram Scheufele and colleagues note, the idea that false and misleading content online

“distorts attitudes and behaviors of a citizenry that would otherwise hold issue and policy stances that are consistent with the best available scientific evidence… [has] limited foundations in the social scientific literature.”

There are many causes of false or simplistic political beliefs and narratives: ignorance, human nature, pre-scientific intuitions, lazy and biased reasoning, and so on. The worldview of highly-educated, cosmopolitan, liberal scientists and journalists is not the default state that people get pushed away from by exposure to disinformation. Demagogues, populism, conspiracy theories, and highly biased, distortive ideologies and worldviews are as old as the human species.

Of course, the fact that the post-2016 alarmism about online disinformation is misguided obviously does not prove that current alarmism about AI-based disinformation is misguided. Nevertheless, many of the reasons why the former worries are greatly exaggerated carry over to concerns about AI-based disinformation. To begin with: persuasion—including political persuasion—is extremely hard.

2. Political persuasion is extremely hard

It’s really, really difficult to change people’s minds. It’s even more difficult to change their minds in ways that lead to changes in behaviour. Most of us intuitively recognise this when arguing at the pub, but then forget it when thinking about persuasion in the abstract. At that point we lapse into thinking that people—other people, that is—are gullible and hence will believe whatever they come across on the internet. As Hugo Mercier demonstrates conclusively in his book Not Born Yesterday, this widespread belief in human gullibility is completely mistaken.

Even when it comes to extremely well-funded, well-organised, and targeted political and advertising campaigns, they routinely have minimal effects. That doesn’t mean all such campaigns have no effects, but it does show that persuasion—real, consequential, long-lasting persuasion of large numbers of people—is exceptionally hard in ways that many people fail to appreciate when they think about topics like online disinformation.

There are several things that make persuasion hard. First, people are strongly disposed to reject information at odds with their pre-existing beliefs, intuitions, and general worldviews. This is partly rational: if someone tells you something that you judge to be very implausible, you should assign it less weight. Nevertheless, people appear to be overly dismissive of other people’s opinions.

Second, persuasion typically depends on trust, which is fragile and difficult to achieve. To accept what someone tells us, we must believe that they are knowledgeable and honest. Otherwise we will dismiss what they say. As I return to below (#3), this means influencers must achieve a reputation for trustworthiness among their target audience, which is hard, and much more difficult than merely creating and publishing content.

Third, unlike in experiments where participants are randomly exposed to persuasive messages, we generally choose which information to consume and ignore. We therefore typically seek out content that aligns with our pre-existing beliefs and preferences and ignore or tune out information that doesn’t.

Fourth, even when people do change their view about something, this is often short-lived. Suppose I trust Bob, and he posts a news story on Twitter that the Pope endorsed Donald Trump for president. I think, “Wow, that’s odd. The Pope endorsed Trump for president.” That looks like successful persuasion, but in reality I will quickly abandon this belief if it’s not confirmed by the BBC, at which point I will also abandon any trust I had in Bob. This is one of many reasons why persuasive effects decay quickly with time.

Finally, even when people do change their mind, they very rarely change more basic attitudes and behaviours, such as their general worldview or the political party they support. In general, people are often set in their ways when it comes to politics. It is difficult to change beliefs. It is really, really difficult to change consequential behaviours such as voting intentions, which are very stable. People rarely appreciate this when thinking about AI-based disinformation, however.

Here is an anecdote that illustrates this. Over Christmas, I was talking to someone about politics. She said something like the following: “Experts are really worried about the effects of artificial intelligence on elections this year.” She had recently read an article about this in the Guardian. I told her I think those worries are greatly exaggerated. She seemed sceptical, so I asked her: “Are you worried that you will be duped into voting for the Conservatives [a political party she hates] because of AI-based disinformation?” She thought about it and then smiled: “Good point.”

In response to these considerations, you might reason as follows:

Ok, political persuasion is hard, but AI-based disinformation might be extremely effective at persuasion. Moreover, it doesn’t need to change most people’s vote to have devastating effects on democracies. It can just change some people’s vote—elections are often decided on small margins—or it might change the beliefs of people with stable voting intentions (e.g., convincing Republicans that the 2020 election was stolen) in ways that have negative consequences.

Maybe. But I think this still greatly overestimates how easy persuasion is, and it runs up against points #3 and #4.

3. The Media Environment is Highly Competitive and Demand-driven

In Western democratic societies, the media environment is highly competitive. People have a limited budget of attention. They must be selective in which information they seek out. In practice, that means being selective about which sources to pay attention to and which to ignore. This selection is based on many different things. How trustworthy is the source? Do they have a good reputation? Do they produce content that I find entertaining or useful? Do their messages cohere with my general worldview? And so on.

Content producers—media companies, internet personalities, professional opinion givers, online conspiracy theorists, etc. - must therefore compete to win people’s attention and trust. This competition is harsh. Anyone who has ever tried to publish their views knows it is extremely difficult to reach an audience with them. To a first approximation, the overwhelming majority of content on platforms like Twitter, Substack, Facebook, or TikTok gets basically no engagement. On Youtube, for example, the median video has zero likes, zero comments, and forty views.

Such competition has several related implications when thinking about AI-based disinformation. First, media is demand-driven, and the media landscape when it comes to politics is already highly specialised for satisfying audience preferences. That means it is exceptionally hard to outcompete existing content producers, especially established, well-funded media institutions (e.g. the BBC, Channel 4 News, the NYT, etc.) that have built up reputations over many years and overwhelmingly possess the largest audiences (see #1). In the context of thinking about AI-based disinformation, then, the question is not whether AI can generate sophisticated, targeted disinformation but whether it can outcompete other, established content producers to win a trusting audience.

Second, to succeed in such markets, content producers must achieve a good reputation (in the eyes of their target audience). One of many things that makes this really hard is that it is strongly in the interests of your competitors to destroy your reputation. In addition to legal accountability for lies and fabrications, this is one thing that keeps lots of media honest, at least when it comes to reporting on narrow matters of fact. (They still select, omit, frame, package, and contextualise such facts in highly misleading ways). If you mess up and get things wrong, competitors therefore have very strong incentives to point this out in order to discredit you. So in thinking about AI-based disinformation, the question is whether sources that use such technologies to produce and transmit disinformation can maintain a trustworthy reputation in environments where it’s strongly in the interests of other content producers to discredit them. Maybe they can, but I think this is a much greater hurdle to cross than most people acknowledge in thinking about AI-based disinformation.

Finally, disinformation itself is overwhelmingly demand-driven. As noted above (#1), the overwhelming majority of citizens get their political information from establishment sources (if they bother to get such information at all). It is only a minority of the population that distrusts and dislikes the establishment that engages with explicitly anti-establishment content and narratives online. On the one hand, content producers that cater to this minority of the population don’t have to worry about being discredited by establishment sources because their audience doesn’t trust establishment sources. Nevertheless, as Felix Simon, Sacha Altay, and Hugo Mercier point out, this audience of very active social media users is already well-served by an informational ecosystem tailored to producing anti-establishment content, and there is little reason to believe that AI-based disinformation will increase the size of this audience. Moreover, even if producers using AI-based disinformation do outcompete existing content producers in this space, the content overwhelmingly preaches to the choir anyway (again, see #1), so it is unlikely to have big effects.

4. The establishment will have access to more powerful forms of AI than counter-establishment sources.

When people worry about misinformation and disinformation, they worry about messages that contradict “establishment” narratives—that is, the consensus views of scientists and experts, public health authorities, government-approved data and statistics agencies, mainstream media fact-checkers, Davos elites, and so on. How worried should we be that AI-based disinformation will fuel counter-establishment content?

Here is a final reason for scepticism that this is a major threat: in Western democracies, the establishment—governments, international organisations (e.g., the EU), mainstream media, corporations legally accountable to governments, and so on—will inevitably have much greater access to more powerful, effective artificial intelligence than counter-establishment sources. That’s what makes them the establishment, after all. For example, this is why it’s very hard to get GPT-4 to produce arguments against vaccines but not in favour of them, or why it rejects requests to defend Trump’s claim that the 2020 US presidential election was stolen but will happily debunk it:

This has an obvious consequence, which can be stated like this: Anything that anti-establishment propagandists can do with AI, the establishment can do better. This means the establishment will be able to outcompete its anti-establishment rivals and attackers when it comes to the use of AI in generating and transmitting persuasive, targeted arguments. It also means the establishment will have access to more effective AI-based technologies when it comes to detecting and combatting anti-establishment narratives online and elswhere.

If anything, this suggests the main thing to worry about when it comes to AI and our informational ecosystem is the exact opposite of what people generally worry about. As Scott Alexander puts it in the context of focusing specifically on “propaganda bots” (i.e., automated disinformation systems),

So the establishment has a big propagandabot advantage even before the social media censors ban disinfo-bots… So there’s a strong argument (which I’ve never seen anyone make) that the biggest threat from propaganda bots isn’t the spread of disinformation, but a force multiplier for locking in establishment narratives and drowning out dissent.

This is an important worry, but it is a radically different worry to the one that people and organisations like the World Economic Forum typically have in mind when it comes to the topic of AI-based disinformation.

Summary

In summary, I think concerns about the effects of AI-based disinformation on Western democracies are probably greatly overstated. When people think about this topic, they ignore many details of how people, democracies, and media actually work. That doesn’t mean there is nothing to worry about or that nobody should be working on addressing relevant problems. When considered collectively, though, I think the four points raised in this essay are enough to pour a big and much-needed bucket of scepticism over the popular alarmism surrounding this topic.

Let me try to steelman this fear (which I mostly disagree with):

Social media was originally thought to be a radical force for democratic change—see the Arab Spring, for instance.

The objective of disinformation was never to change minds, but to reduce trust in anonymous online interactions. See Russia’s human-based propaganda methods.

Thus, disinformation blunts the value proposition of social media platforms in allowing individuals to coordinate political action.

So it’s really an opportunity cost we’re talking about here in preventing social media from achieving its full potential—which may have been oversold in the first place.

My own view is that very few actors will attempt to target “political trust” as an abstract force. Instead, we should be significantly more concerned about financially-motivated scams targeting individuals.

I appreciate you writing this, it seems like a good and important post. I’m not sure how compelling I find it, however. Some scattered thoughts:

In point 1, it seems like the takeaway is “democracy is broken because most voters don’t care about factual accuracy, don’t follow the news, and elections are not a good system for deciding things; because so little about elections depends on voters getting reliable information, misinformation can’t make things much worse”. You don’t actually say this, but this appears to me to be the central thrust of your argument — to the extent modern political systems are broken, it is not in ways that are easily exacerbated by misinformation.

Point 3 seems to be mainly relevant to mainstream media, but I think the worries about misinformation typically focus on non-mainstream media. In particular, when people say they “saw X on Facebook”, they’re not basing their information diet on trustworthiness and reputation. You write, “As noted above (#1), the overwhelming majority of citizens get their political information from establishment sources (if they bother to get such information at all).” I’m not sure what exactly you’re referencing here, but it looks to me like people are getting news from social media about ⅔ as much as from news websites/apps (see “News consumption across digital platforms”). This is still a lot of social media news, which should not be discounted.

I don’t think I find point 4 compelling. I expect the establishment to have access to slightly, but not massively better AI. But more importantly, I don’t see how this helps? If it’s easy to make pro-vaccine propaganda but hard to make anti-vax propaganda, I don’t see how this is a good situation? It’s not clear that propaganda counteracts other propaganda in an efficient way such that those with better AI propaganda will win out (e.g., insularity and people mostly seeing content that aligns with their beliefs might imply little effect of counter-propaganda existing). You write “Anything that anti-establishment propagandists can do with AI, the establishment can do better”, but propaganda is probably not a zero-sum, symmetric weapon.

Overall, it feels to me like these are decent arguments about why AI-based disinformation is likely to be less of a big deal than I might have previously thought, but they don’t feel super strong. They feel largely handwavy in the sense of “here is an argument which points in that direction”, but it’s really hard to know how hard they push that direction. There is ample opportunity for quantitative and detailed analysis (which I generally would find more convincing), but that isn’t made here, and is instead obfuscated in links to other work. It’s possible that the argument I would actually find super convincing here is just way to long to be worth writing.

Again, thanks for writing this, I think it’s a service to the commons.

Thanks for this. A few points:

Re. point 1: Yes, I agree with your characterisation in a way: democracy is already a kind of epistemological disaster. Many treatments of dis/misinfo assume that people would be well-informed and make good decisions if not for exposure to dis/misinfo. That’s completely wrong and should affect how we view the marginal impact of AI-based disinformation.

On the issue of social media, see my post: https://www.conspicuouscognition.com/p/debunking-disinformation-myths-part. Roughly: People tend to greatly overestimate how much people are informing themselves about social media in my view.

Re. point 4: I’m not complaining it’s a good thing if establishment propaganda outcompetes anti-establishment propaganda. As I explicitly say, I think this is actually a genuine danger. It’s just different from the danger most people focus on when they think about this issue. More generally, in thinking about AI-based disinformation, people tend to assume that AI will only benefit disinformation campaigns, which is not true, and the fact it is not true should be taken into consideration when evaluating the impact of AI-based disinformation.

You write of my arguments: “They feel largely handwavy in the sense of “here is an argument which points in that direction”, but it’s really hard to know how hard they push that direction. There is ample opportunity for quantitative and detailed analysis (which I generally would find more convincing), but that isn’t made here, and is instead obfuscated in links to other work.”

It’s a fair point. This was just written up as a blog post as a hobby in my spare time. However, what really bothers me is the asymmetry here: There is a VAST amount of alarmism about AI-based disinformation that is guilty of the problems you criticise in my arguments, and in fact features much less reference to existing empirical research. So it felt important for me to push back a bit, and more generally I think it’s important that arguments for and against risks here aren’t evaluated via asymmetric standards.

Elaborating on point 1 and the “misinformation is only a small part of why the system is broken” idea:

The current system could be broken in many ways but at some equilibrium of sorts. Upsetting this equilibrium could have substantial effects because, for instance, people’s built immune response to current misinformation is not as well trained as their built immune response to traditionally biased media.

Additionally, intervening on misinformation could be far more tractable than other methods of improving things. I don’t have a solid grasp of what the problem is and what makes is worse, but a number of potential causes do seem much harder to intervene on than misinformation: general ignorance, poor education, political apathy. It can be the case that misinformation makes the situation merely 5% worse but is substantially easier to fix than these other issues.

In general I agree (but I already did before reading the arguments) there’s probably a hype around AI-based disinformation and argument 2, i.e., that we actually don’t have a lot of evidence of large change in behavior or attitudes due to misinformation, is the strongest of the arguments. There is evidence from the truth effect that could be used to argue that a flood of disinformation may be bad anyway; but the path is longer (truth effect leads to slightly increased belief than then has to slightly influence behavior; probably something we can see with a population of 8 billions, but nothing with losses as large as war or environmental pollution/destruction). The other arguments are significantly weaker, and I’d note the following things:

It’s interesting that, in essence, the central claim relies on the idea that there’s widespread misinformation about the fact that misinformation does not impact people’s attitudes, behavior, etc., that much. [Edit: In general, I’d note that most studies on misinformation prevalence depend on a) representativeness of the data collected and b) on our ability to detect misinformation. As for the first, we don’t know whether most studies are representative (although it is easy to suspect they aren’t due to their recruitment methods; e.g., MTurk and Prolific) nor in terms of the experiences these already-probably-not-representative people have (they mostly focus on one platform, with X, formerly Twitter, dominating most research). In terms of the second, self-reported misinformation exposure and lists of URL “poor quality websites” are probably very noisy (the latter depending on how exhaustive the URL lists are and relying on the assumption that good quality news don’t ever share misinformation and that bad quality news don’t ever share actual information; and of course this does not allow the detection of misinformation that is not shared through an URL link but by user’s own words, images, videos, etc.), and alternatives such as human fact checkers and fact-check databases are also not perfect, as they reflect the biases (e.g., in the selection of what to fact-check in the first place) and lack of knowledge that the human curators naturally have. In sum: We should have a good amount of uncertainty around our estimates of misinformation prevalence.]

The dig at the left with “aligns better with the prevailing sensibility and worldview of the liberal commentariat” is unnecessarily inflammatory, particularly when no evidence of difference in perspective between left and right is advanced (and everyone remembers how Trump weaponized the term “fake news”; regardless, left-right asymmetries aren’t settled with anecdotes, but with actual data; or even better, instead of focusing on “who does it more” focusing on “stopping to do it”).

It sounds odd to me to assume in 4. that what people fear is only or even mostly about anti-establishment propaganda. In part because, without any evidence, this is just mind-reading, in part because, given modern levels of affective polarization, the most likely is that when one’s party is not in power (or has only recently left), we are more likely to believe that the president (we don’t like) is using their powers for the purposes of propaganda, and so are more worried about establishment propaganda as it then becomes salient (e.g., in the US context: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/01/24/politics/trump-worst-abuses-of-power/index.html | https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/14/business/media/fox-news-biden-dictator-trump.html).

Great post, Dan! Relatedly, readers may want to check #180 – Why gullibility and misinformation are overrated (Hugo Mercier on the 80,000 Hours Podcast).

Executive summary: The widespread alarmism around AI-based disinformation threatening Western democracies is greatly overstated due to mistaken beliefs about persuasion, media, and establishment power.

Key points:

Online disinformation is not actually the root cause of most modern political problems.

Political persuasion is extremely difficult, even with sophisticated targeting.

Media competes for limited attention, requiring building reputation and audience trust.

Establishment forces will have access to more advanced AI than anti-establishment ones.

Counter-establishment content mainly preaches to a minority choir rather than persuading.

The alarmism around AI and disinformation neglects how people, media, and power actually function.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

A few things I that I find not quite convincing: micro targeting, long term connection, slow changes, nudges, usability outside of just message—so that the connection is maintained by the person, profiling.

Lets imagine that some entity would provide a servce for free (or very cheap), that does something useful, but also because of lots of interactions has a lot of time to gently push some idea. And also collect all the interaction history to make this interaction more efficient. Sure, one message wont do it. But thousands of messages, over many months, highly personalized, context adapted, personality infused, would convince even me.

Surely we are far away from AI being so easily available to just access it from your phone, it being able to remember your previous requests, it being just smart enough to nudge you a little every time, it being sufficiently advance to form an illusion of personality. That wont happen during our lifetime, right?

Im not so worried about establishment vs opposition, because as you say, they both can do the same. What I am worried is the general course of action. What will both of them do? And if both of them will resort to tactics I described, the democracy will change significantly.