In this academic session, Zach Groff, a PhD student at Stanford University whose research areas include welfare economics, discusses a 1995 paper whose authors argued that nature contains more suffering than enjoyment. After analyzing the model used in that paper, Groff found that an error negated its original conclusion, and that evolutionary dynamics imply that enjoyment may predominate for some species. In addition to this result, Groff discusses suggestions for the empirical study of wild animal welfare.

Below is a transcript of Zach’s talk, which we’ve lightly edited for clarity. You can also watch it on YouTube and read it on effectivealtruism.org.

The Talk

Thank you. Today I’m going to present a paper I wrote with Yew-Kwang Ng, an economist at Fudan University, who anticipated many of the ideas in the effective altruism movement decades earlier through his work on utilitarianism. Our paper is called “Does Suffering Dominate Enjoyment in the Animal Kingdom? An Update to Welfare Biology.”

The core of the paper is a correction of an error in a 1995 paper by my coauthor, in which he [explored] the idea of welfare biology and — in one of the first academic papers on the subject — proposed that we study wild animal well-being systematically. Among the many perceptive conclusions he offered [was his theory] that suffering is doomed to dominate enjoyment in the wild, based on a number of reasonable assumptions.

It turns out that this finding is incorrect. When the error is fixed, the balance of suffering and enjoyment can go either way. There could be more suffering than enjoyment, or more enjoyment than suffering. I should also note that I’ll be using the terms “suffering,” “pain,” “enjoyment,” “happiness,” and so on fairly casually. These are often controversial terms; There are a lot of debates in economics about whether you can quantify and compare these things. I’m going to take for granted [that we can], and [in doing so], see what we can assume.

I think revisiting [Ng’s original] theory is a promising [place to start] as we work to establish organizations in wild animal welfare, because the paper was one of the earliest to [address] this question [of suffering and enjoyment].

Ng’s 1995 paper asks three questions:

1. Which animals have experiences — and specifically, experiences that can be said to be positive or negative? Those are the experiences we’re concerned about when trying to improve well-being.

2. Is their welfare positive or negative, and how can we figure that out?

3. What can we do to help wild animals?

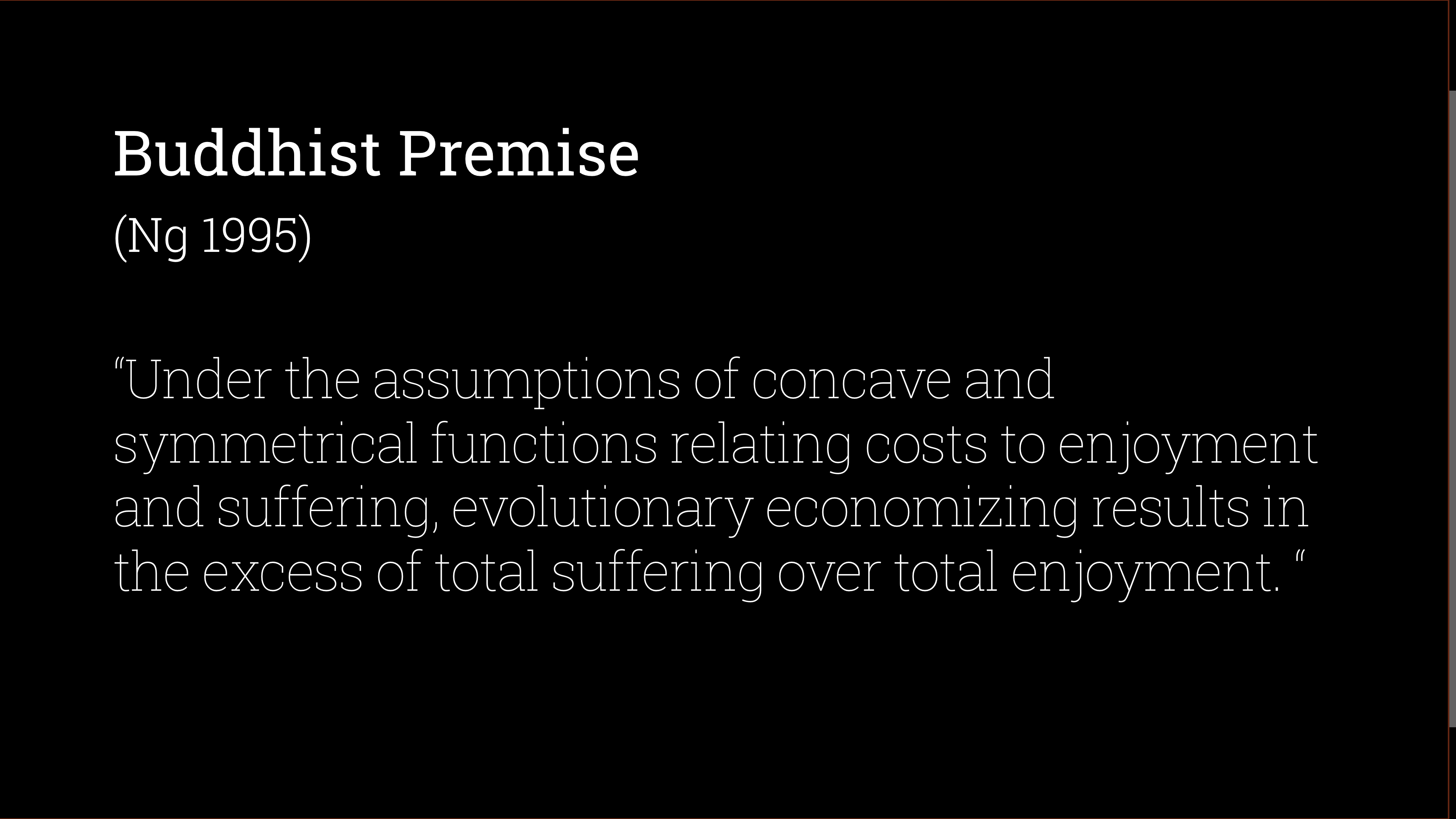

In addressing whether animals have positive or negative well-being, Ng arrives at what he calls “the Buddhist Premise,” a claim that under the assumptions of concave and symmetrical functions relating costs to enjoyment and suffering, we should see the dominance of suffering over enjoyment. I’ll go over those conditions in a bit.

This was one of the first papers to look at this question. And to date, the vast majority of papers on the issue [address] the moral question of what our obligations are toward wild animals. There are very few that try to tackle what it’s like to be a wild animal. [Ng’s paper] is also cited and commonly discussed in effective altruism circles.

The conditions that Ng uses to derive this Buddhist Premise are listed on the left.

First, Ng posits that suffering and enjoyment serve to increase evolutionary fitness by inducing organisms to engage in behaviors that increase their chances of reproductive success — and discourage organisms from engaging in behaviors that detract from reproductive success. This is an assumption that basically ties positive emotions to behaviors that are selected for and negative emotions to behaviors that are not selected for.

If it’s the case that positive and negative emotions have this kind of reinforcing effect and induce behavior that increases reproductive success, then there has to be a reason why we don’t see infinite amounts of enjoyment and suffering. So Ng assumes that enjoyment and suffering must be costly to produce; there must be some type of evolutionary cost to an organism experiencing enjoyment and suffering.

Furthermore, Ng assumes that these costs increase with the magnitude of suffering or enjoyment. [In other words,] as you invest more in creating a positive or negative experience, you get less bang for your buck.

So in the graph from the 1995 paper [on the right-hand side of the last slide], the X axis shows the cost of suffering or enjoyment, or the amount of resources invested in producing a certain experience. And the Y axis is the magnitude and direction of the experience. Basically, as you increase the amount invested in the costs of enjoyment or suffering, the curve flattens out. It is also assumed that the costs are similar for enjoyment and suffering; there’s not any reason to think that it should be easier to produce the sensation of happiness or the sensation of suffering.

Under these conditions, Ng arrives at the Buddhist Premise. I should also note that for symmetry, you don’t necessarily need the functions to be exactly the same. You just need them to be similar enough.

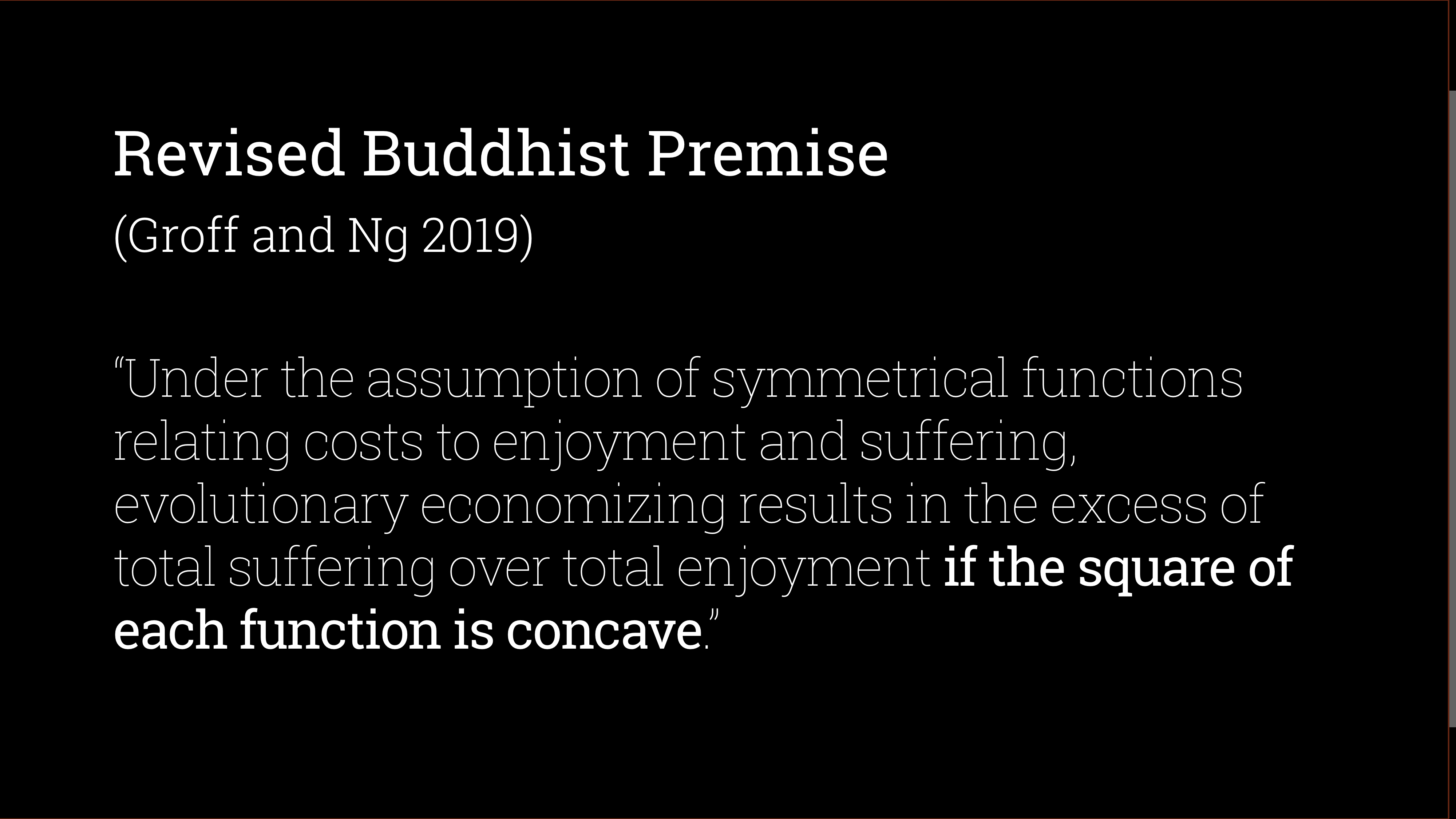

We show that when you do the math correctly, you arrive at this revised Buddhist Premise.

It looks largely the same under the assumption of symmetrical functions relating costs to enjoyment and suffering. Evolutionary economizing results in the axis of total suffering over total enjoyment if the square of each function is concave. Now, rather than needing the enjoyment produced for certain costs to flatten out, we need the _squared_ enjoyment to flatten out. This might sound weird and technical, and you might not know what that means. I think that’s actually [an appropriate] reaction. There’s not really much of an intuitive [sense of] what this means or whether we should expect this condition to hold.

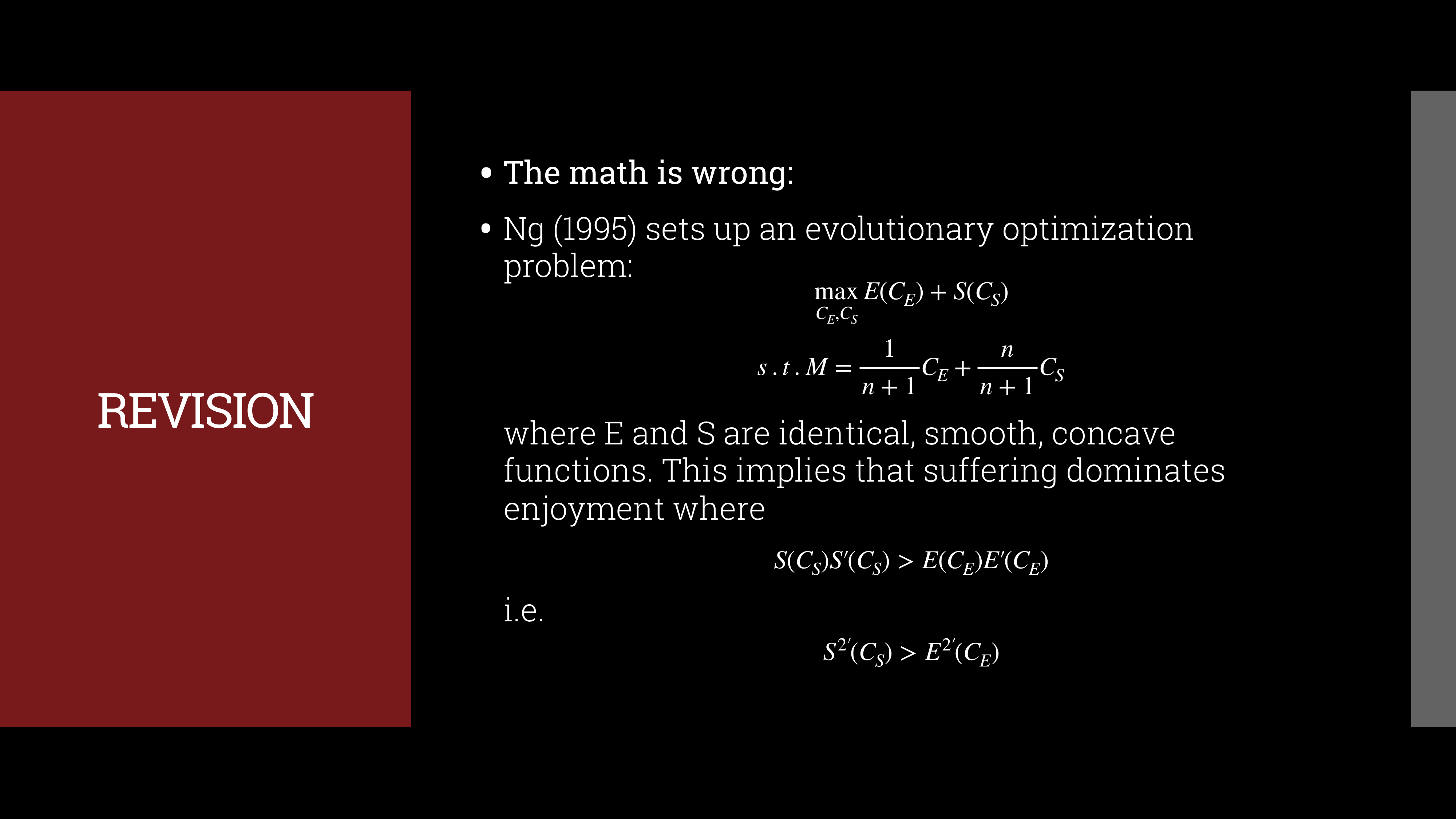

This [slide] shows the math [involved in more detail]. Essentially, Ng sets up what we call an “optimization problem,” where evolution selects for genes that maximize the total amount of enjoyment and suffering, because enjoyment serves to induce behaviors that increase reproductive success and suffering discourages behaviors that detract from it.

You could also think of suffering as negative enjoyment: the difference between what you experience when you behave in ways that increase the likelihood of reproductive success and what you experience when you behave in ways that detract from it.

In that case, the costs of enjoyment and suffering, [shown] on the second line [in the slide above], are weighted by the probability of experiencing enjoyment or success and suffering or failure. That’s to say that “N” [in the slide above] is the number of organisms failing or suffering for every organism succeeding and achieving enjoyment. The reason for this weighting is that evolution will select for genes that minimize the expected cost of suffering and enjoyment; that cost will be weighted by how likely you are to experience these things.

[When considering] this problem [as it relates to] Ng’s 1995 paper, the function is not concave — and suffering does not dominate enjoyment. Instead, there is a condition [indicating] that the square of the functions must be concave for suffering to dominate enjoyment in nature.

This inequality really does not give rise to any obvious intuition. And so, based on this model, we arrive at complete uncertainty. The model cannot tell us whether suffering or enjoyment dominates. There are a lot of functions with the property that the square of the function is concave — and a lot without it. And sometimes functions have this property in some parts of their domain and do not have it in other parts of their domain.

I’ll note that Ng provides two arguments for thinking that there’s more suffering than enjoyment in nature: (1) the mathematical argument that we just discussed and corrected and (2) the intuitive argument, similar to the one you often hear in effective altruism circles, that many species of animals’ offspring die shortly after being born. Based on that, it seems that there should be more suffering than enjoyment in nature. Therefore, the error that we’ve corrected [applies to] the mathematical argument, but does not directly challenge the intuitive argument.

Once we [determine] that you can’t say which way the balance goes, a question that might arise is whether you can make additional assumptions. What happens if we assume there is a specific relationship between the costs of producing suffering and enjoyment, and the amount produced? We can assume that certain costs producing enjoyment or suffering are logarithmic. The reasons are very speculative; I would not assume this in general. I’m simply assuming it for the sake of exploring the dynamics in this model.

The first reason is called the Weber-Fechner law in psychology: a finding that the reaction to a change in a stimulus is proportional to the initial magnitude of the stimulus. So a change in the length of a line is noticed in proportion to how long the line is. Also, happiness studies in economics have found that happiness increases logarithmically with income. [Both of these analogies] require huge leaps; again, this is very speculative. We do this purely for the sake of being able to illustrate the model a little bit and play around with it to see what we can find.

We find that even with this more specific function for costs, we still get an “anything goes” result in which the balance [of net suffering or enjoyment] can go either way. Two things happen that explain this result. First, when a lot of organisms are born and then immediately die or in some way fail reproductively, obviously the number of organisms suffering increases. At the same time, each failing organism suffers less under this model. Again, this is not to say that this is necessarily true in general, but under the model here, we find that as “N” or the number of organisms that succeed increases, it becomes more costly to invest in suffering, because the cost is weighted by the probability of failing or succeeding.

For example, if you compare a species of animals where 50 out of 100 of the offspring die shortly after birth to a species where 99 out of 100 die shortly after birth, this model suggests that in the latter case, each one of those 99 that fail should suffer less.

Not only is it the case that the balance of suffering or enjoyment can go either way, we can’t even find a relationship between the rate of evolutionary failure and the balance of suffering or enjoyment. It could be that as the likelihood of dying an early death increases, it becomes more likely that the species experiences net suffering — or more likely that the species experiences net enjoyment.

This graph is an illustration of that. On the X axis we have the number of animals dying or failing to achieve reproductive success. And on the Y axis we have the net amount of suffering. Zero means that there is an equal amount of suffering or enjoyment. As you go up [on the graph], suffering dominates, and as you go down, enjoyment dominates. “M” is a number whose meaning is honestly open to interpretation and I wouldn’t [ascribe] too much meaning to it. In our model, M was the total cost of suffering or enjoyment, so one interpretation might be that the size of the organism or the intensity of experiences [can affect the balance of suffering or enjoyment]. But I would caution that this is very speculative. The deeper point is that by altering a parameter in the equation, you can [change] the balance of suffering or enjoyment. You can affect not only whether it is positive or negative, but whether it goes up or down [depending on] the probability of [a species] failing to reproduce.

Where does this leave us? A lot of people say that this is cause for optimism because [we’ve updated our thinking] from a result indicating that there was net suffering in nature. But [we’ve not shown] that there’s net enjoyment in nature. Our result simply says that from this model, we cannot derive a finding.

However, I think there’s cause for optimism in research. Working with this model shows how we might make progress on high-level questions in wild animal welfare.

I propose a three-step process to pursuing research:

1. List all of the possible evolutionary explanations for suffering or enjoyment. This [task] is at the intersection of philosophy and evolutionary biology.

2. [Identify] the empirical facts that we would expect to see in the world if the explanations [we arrive at in the first step] hold. This requires thinking about what “the costs of suffering or enjoyment” could mean. Do we mean the energy cost — that experiencing intense emotions as a side effect is distracting? And then how can we quantify the intensity of these experiences? There are probably a number of different measures yet to be developed. But by thinking about these measures and trying to explore these relationships, we might be able to say, “There are facts that don’t seem to match a certain evolutionary picture and do seem to match this other picture.”

3. Use our cost functions to work through the type of optimization problem that I showed a few slides ago. [This will allow us to] arrive at a sense of which way the balance [of net suffering or enjoyment] is likely to go. That’s going to lead to results that are much more fine-grained — and much less obvious — than the Buddhist Premise. [We’ll be able to determine what kinds of situations in which] you would expect more or less suffering. And that should allow us to make some progress on these issues.

Finally, it’s rare to hear the mathematical argument from this paper mentioned in EA discussions. You don’t hear people talking about the optimization problem or the specifics of this paper. I think the intuition behind the paper does have some relationship to the mathematical model [to the extent that] the amount of suffering each organism experiences goes down as the [survival rate] goes up. But if you look at the academic literature and even the nonacademic literature on wild animal suffering, you see a lot of citations [pointing to] the claim that suffering dominates enjoyment. I think that even if we’re not consciously making the mathematical argument in our heads, there’s a good chance that we’ve anchored our thinking to it.

If we have anchored on the result, that’s cause [to take] a more uncertain view of the balance of enjoyment and suffering in nature. Through a combination of the three steps I laid out, and by using theory from evolutionary biology, philosophy, neuroscience, economics, and empirical study, we can make further progress on answering these high-level questions. Thank you.

Moderator: Our discussant for this session will be Michelle Graham. Michelle is a researcher at Wild Animal Initiative. Her projects have included work on research and intervention, prioritization, and categorization. In addition, she’s currently pursuing a PhD in engineering mechanics at Virginia Tech. Her dissertation focuses on the movement behaviors of jumping and gliding snakes. Previously, Michelle studied physics and philosophy at the University of Oxford, and has worked with animals in shelter, veterinary, farm, and zoo environments.

Michelle Graham [Discussant]: Hello. I think this is a really interesting paper. Overall, I’m very optimistic about the future possibilities for economic-style and biology-style approaches to come together and [allow us to make] really good progress on broad questions about wild animal welfare.

I’m going to make a point that I think Zach will agree with: At the moment we have very, very little empirical data about anything in nature that is relevant to these issues. A general principle of using models is that you need to be able to check your assumptions against data. And at the moment, I don’t think we have enough data to assess the assumptions of Zach’s model and test its predictions against results. We don’t even have a framework in welfare biology right now for checking results.

So I think that, for now, we should be thinking about models as hypothesis generators and, as Zach does, using them as ways to explore what kinds of questions we might be asking to better inform our models.

One thing I particularly like and want to explore with you, Zach, is the common practice in economics of optimizing [in terms of] the optimal of a cost function. Evolution is rarely able to truly optimize on individual traits because there are a lot of constraints in evolution; animals carry genetic baggage, and the history of their ancestors going way into the past governs how they are able to evolve now.

An example is the human backbone. If you were going to engineer a bipedal [animal], you would not make your spine like ours. But because our evolutionary history [includes time spent] in trees, we have traits that are adapted for arboreal life that have now moved into terrestrial environments. It seems to me that under the framework [you presented] it’s quite complicated to optimize under these totally unknown sets of constraints. And I wonder how you might think about that using an economics framework.

Zach: Yeah, I think this is a very good point. It makes complete sense and ultimately underlines why, [in my proposed steps for research], the first one is to think through the different theories in evolutionary biology. It’s not something I ever would have thought of from an economic standpoint. My thought [process] was: Let’s think of all of the relationships between cost and suffering and the optimization problem — rather than [considering] what type of problem we should begin with.

I think that, more generally in economics, we assume things get optimized on a global scale, which is an assumption that’s troubling not just when we’re going outside of our field. Even in our field, we assume that people optimize in general, when often it’s a local optimum or not even an optimum. I think this is a good example of that — and a reason why we need to constantly be in dialogue with people who’ve thought about evolutionary dynamics in wild animals.

Moderator: We have a few questions from the audience. One person asks, “What evidence is there that premature death equates to suffering?”

Zach: Well, that’s a big question. I think the evidence on all of these wild animal welfare questions is very uncertain. And despite all of the research and biology that has been done, no one has really focused on this question for very long.

There are people in effective altruism who’ve talked about this, and in the context of wild animal suffering, Brian Tomasik’s essays have been pretty influential, although I think the view that suffering dominates enjoyment in nature has been moderated somewhat among people working at wild animal welfare nonprofits. But in general, there’s a lot of discussion of this early-death phenomenon where you have, say, 2,000 offspring and one survives. It’s often a very quick intuitive claim that [in such cases], those who died presumably had a pretty bad life.

Michelle: I would also say that I think it’s more intuitive for animals that are more closely related to us, specifically [in terms of] the relationship between failing to reproduce and welfare. If you take an example of social insects like ants, where the vast majority of ants are not reproductively active and just the queens are, that isn’t necessarily a strong claim. You need to moderate [your opinion relative] to how much you know about the way the animal works.

Moderator: We have another question from an audience member who claims that the premise that greater intensity of enjoyment or suffering having a higher cost is counterintuitive. Suppose there is no difference in cost. Does that have implications for whether net experience is positive or negative?

Zach: Yeah, this idea of “costs” is kind of counterintuitive. I think there are a lot of [scenarios] that don’t [reflect] a specific cost of suffering or enjoyment. It’s more like there’s a complex web of connections between suffering, enjoyment, and other things. And through this complex web of costs, as suffering goes up, other good things go up, some good or bad things go down, etc.

[The model I presented] is a way of approximating that web of connections. Somewhere in that web of connections there must be something [keeping animals from experiencing] an infinite amount of suffering or enjoyment. We [reached the assumption about higher cost] because in this optimization model, [it’s necessary]. If enjoyment and suffering [are cost-free] and help reward and punish behavior, then you would have an infinite amount of suffering and enjoyment.

But I do think it’s a point well-taken. This may not be an accurate way of describing it. And if that’s the case, we need to rethink how we set up the problem.

Michelle: Yeah. I will say that it’s reasonable to [assume] that if pain is, in fact, a reinforcement learning mechanism, it is common for reinforcement learning mechanisms to have diminishing returns. For example, if you punish [an animal] for behaving a certain way, and you continue to do so over and over, [the result can be] learned helplessness. The animal [may] just stop responding to the stimulus at all. So it’s not a totally unreasonable assumption. It’s just something we don’t have a lot of empirical data [to support].

Moderator: And this might be a good wrap-up question: What are your own best guesses as to the predominance of suffering in nature?

Zach: I think my attitude is that, basically, we’re uncertain, and [we should] proceed as we would with complete uncertainty. People have asked me, “Does this mean that wild animal suffering is a lower priority because the scale is less?” I don’t think that’s the case. We didn’t show that there are fewer wild animals out there and honestly, this [paper] probably doesn’t show that there’s more or less suffering per se. If you thought that there’s a large amount of suffering out there before, I think you should still think that. Maybe the main thing [this paper] does is suggest that we should pause before engaging in any kind of radical action based on thinking that there’s net suffering.

Michelle: I definitely agree and also refuse to answer the question. [Laughs] But I will say that I think even if we knew for certain that average net welfare in the wild was positive — which is something that most people think about humans — that doesn’t mean you abandon the problem of wild animal welfare. We care about human welfare even though the average human potentially has a good life. It’s not that average net welfare being positive indicates that there are no problems, or that all problems are fixed. I definitely encourage people to think about more than a single number as a metric [for determining] the scale of animal problems. Animal problems are really important because there are tons of animals. And animals matter. And if they face problems, those problems are high in magnitude.

Moderator: That’s a great way to end this session.

Zach’s EA Forum post on this.