Stakeholder-engaged research in emerging markets: How do we unlock growth in Asian animal advocacy?

Thanks to Kaho Nishibu, Elly Nakajima and Ella Wong for providing feedback on this post.

Summary

Large, emerging markets, particularly in Asia, are key to improving global animal advocacy, but research on what works best to support and promote these movements remains neglected

Capacity building interventions are often discussed in the context of supporting emerging markets, but effective implementation requires well-informed, country/region-specific strategies

We argue that stakeholder-engaged research methods are particularly suited for identifying effective approaches in these countries, where we know less about what works, and where different cultural and contextual factors may have tremendous influence on the success of interventions

We summarise two studies to illustrate how stakeholder-engaged research can be used to understand capacity building opportunities in Asia

1) Animal Advocacy Africa’s Asia Landscape study, which engaged advocates to map and rate different potential interventions

2) Animal Alliance Asia’s Animal Advocacy Forum study, which held interactive forums to explore challenges to movement growth in multiple Asian countries

We conclude with some of our learnings from using stakeholder engaged methods over the last 3 years, and where we hope to take it from here

We’re also launching a series of co-creation workshops later in 2023, with the vision of building a Research-to-Action lab, where we can systematically facilitate the process of translating research into effective action for animals. Please get in touch at team@goodgrowth.io if you’re interested in participating or funding this initiative.

Introduction

This is part of a series of forum posts about stakeholder-engaged research (SER) methods in EA. In our previous forum posts, we’ve introduced the idea of stakeholder-engaged research—integrating various stakeholders into the research process to improve research outcomes and increase research usage. Our first piece looked at Good Growth’s origins in the EA Meta/ Community Building space, we then looked at how we have used a similar framework to support the animal welfare community in China. This third piece expands the scope to Asia more broadly, taking a detailed look at two landscape studies to understand how stakeholder-engaged research can be used to improve movement capacity in emerging locations.

Background

In the previous post, we highlighted the reasons for focusing on animal welfare in emerging markets- growing economies with increasing levels of animal product consumption- using China as an example. Relieving animal suffering in these countries is hugely important, neglected and, given recent successes in animal advocacy globally, looks potentially tractable. As one of the key bottlenecks is building effective local movements throughout Asia, this post looks at ways of addressing this.

Broad interest in large Asian countries means that funding is generally available for projects, particularly from EA-aligned farmed animal funders. A recent survey of funders found that: “Asia was the most-often-mentioned region for expansion, particularly India and China, followed by Africa”. However, in 2021, only $37.5 million (under 20% of the total year-on-year funding) went to projects outside of North America and Western Europe. This mismatch between interest and funding allocation seems to indicate that there aren’t enough promising projects to meet the funders’ capacity.

Currently, a high proportion of funding in neglected countries goes towards supporting international organisations. For example, since 2016, over 75% of Open Philanthropy’s Asian grants in farmed animal welfare have gone to international organisations[1]. Newly-incubated EA charities are also focusing their work on emerging markets (Fish Welfare Initiative, Shrimp Welfare Project). This has the advantage of bringing existing talent, infrastructure and resources from the EA-aligned global animal advocacy movement into neglected regions.

However, while there are merits to this approach, we think there are major advantages to supporting existing local organisations and individuals, for example:

Local advocates know the culture, politics and languages of their home country, and recognise the distinct challenges faced by advocates there

They also have ‘skin in the game’ and strong attachments, therefore have greater incentives and ability to commit long-term to their home country

Perceptions of advocacy movements as ‘home-grown’ are likely to build more local support from the public and government

But most animal advocacy organisations in Asia are still relatively small and have access to fewer resources than their international counterparts. As such, there is increasing interest in building capacity for Asian animal advocacy organisations.

Capacity building encompasses many activities that make animal advocates better able to do their jobs, from providing access to funding to pro-bono support, or facilitating cooperation with other groups. It can focus on making individuals, organisations or systems more effective, and can support, or work in tandem with community or movement building- in our case, growing the community of people who are working to improve outcomes for animals.

Thanks to recent developments elsewhere, we have increasingly good evidence of how a large, high-capacity animal-advocacy movement can drive meaningful change. Essentially, the major progress made in the animal movement in the west, from rapid increases in cage-free egg production to the collapse of the European fur industry, has been made possible due to a network of a large infrastructure of trained staff, volunteers, supporters, plant-based consumers, experts within industry and academia, and a network of mutually supporting organisations.

To achieve similar success in Asia, regional movements will likely require increased capacity. Capacity building interventions can use insights gained from the international animal advocacy movement, climate movement, and other successful social movements to equip organisations with the tools to become more effective and impact-focused. This might involve improving research use, prioritisation, promoting better epistemics, and improving M&E practices.

Capacity-building interventions in the Asian animal advocacy movement have a few other characteristics that make them more promising:

Building scale. Working with an existing network has the potential to amplify the impact of advocacy work through harnessing the high potential of large-scale social movements for creating change.

Low-hanging fruit. There are likely to be some simple, cost-effective interventions that local advocates are already well-placed to address that can have a significant impact, such as establishing cage-free industry standards where none currently exist (as has recently happened in Thailand and China), and integrating already-aligned individuals into the advocacy movement.

Path dependency. While the Asian animal advocacy movement is growing, there is outsized potential to shape the movement in an effective and evidence-based way

How can stakeholder-engaged research facilitate capacity building?

Effectively capacity building for local animal advocacy organisations in Asia requires a nuanced understanding of various cultural, economic and political contexts. It also requires integrating these insights into how we design and implement interventions. We argue that stakeholder-engaged research provides a promising approach for achieving these goals.

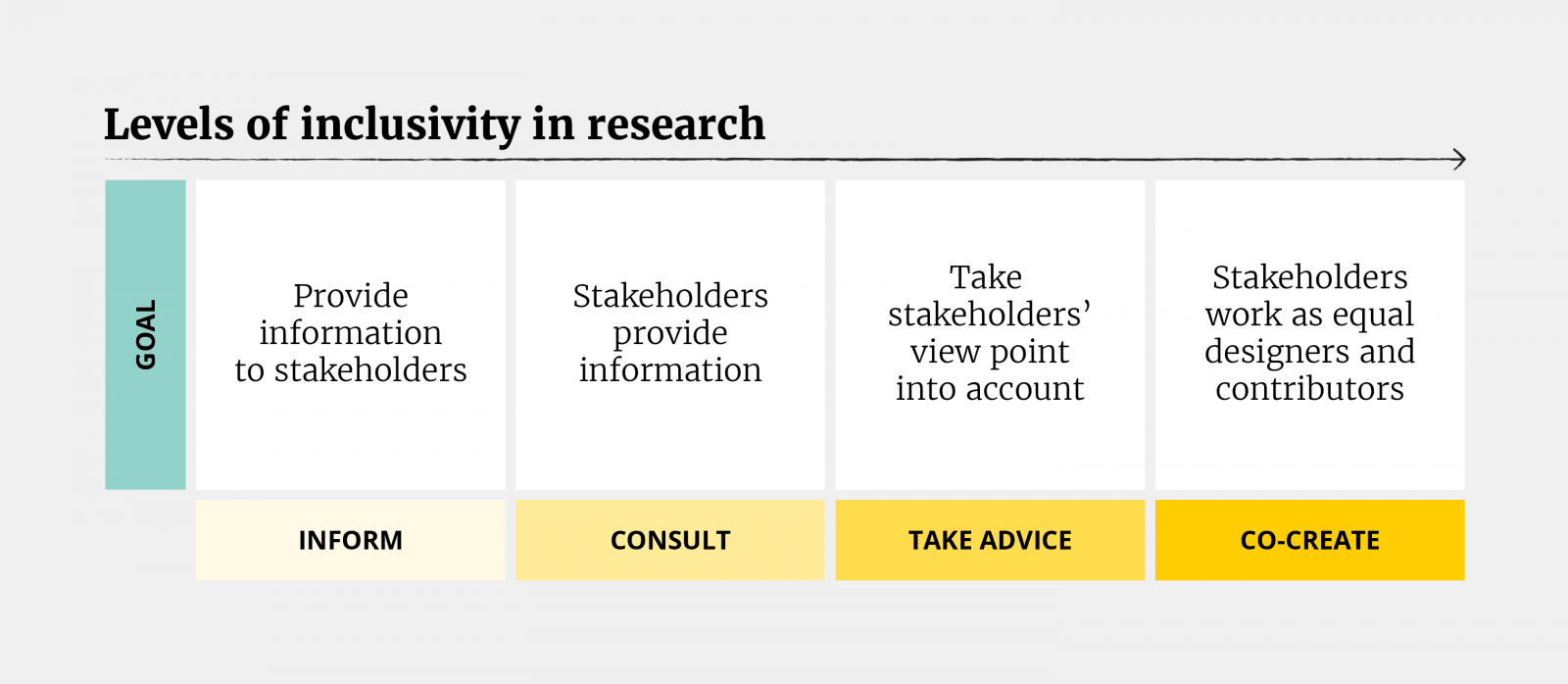

Stakeholder-engaged research (SER) can range from simply exchanging information amongst stakeholders, to consulting with and taking advice from stakeholders, to co-creating research. Different levels of engagements are associated with different goals and outcomes. Lower-level engagement, such as disseminating findings to stakeholders, can facilitate uptake of research and reduce misunderstandings. Higher levels of engagement, such as research co-creation or participatory research, can have distinct advantages when there are numerous interest groups that will be affected by and able to act upon research findings, whose viewpoints provide genuinely valuable, difficult-to-obtain information, and who have the ability to contribute to the research and implementation process.

These approaches expect that stakeholders will contribute significantly to the project. Although there might be some costs to researchers in involving more stakeholders, primarily the initial time and resource investments, there are some obvious benefits:

Joint ownership fosters an environment where stakeholders are more inclined to contribute their valuable insights to the research process.

There are more incentives for stakeholders to actually use the research, as they’ve contributed to it and feel a sense of ownership

Stakeholder-engaged research (SER) establishes pathways for communication and collaborations that support continued cooperation, which can be more efficient in future iterations

Examples of high-engagement approaches are well-established in the medical field, where medical professionals are increasingly encouraged to engage at increased levels in the research projects, and where co-creation of research with a capacity building element has been identified as a valuable tool for improving patient outcomes.

Another interesting dimension is that stakeholder-engaged research can be used both on and as capacity building.

While research is often seen as informing impactful interventions, what is often overlooked is that the process of research itself can produce capacity building outcomes. Using stakeholder engaged research methods can produce more useful, informed and relevant findings and insights—in the case of capacity building, making sure that research correctly identifies the relevant contextual factors, and gets to the real questions faced by organisations. But the process of being engaged in the research actually allows organisations- animal advocacy nonprofits in our case- to build their own capacity.

The benefits of SER are demonstrated in a recent meta-review of 675 studies, which found that the reported outcomes of engaging stakeholders included:

“(1) stakeholders experienced personal benefits from working in a research partnership (n = 104 of 675; 15%); (2) partners reported that the research partnership can create high quality research (n= 80, 12%); (3) stakeholders experienced increased capacity, knowledge and skills related to research processes (n = 74, 11%); (4) partners reported that the research partnership can create increased capacity to conduct and disseminate the research (n= 69, 10%); and (5) partners reported that the research partnership can create system changes or action (n= 65, 10%).”

So, while research outputs can be improved through SER, the mere process of performing stakeholder-engaged research can also be an inherently capacity building process. Stakeholders who are involved throughout the research process, for example, can become more aware of existing research (e.g. through the literature review process) and better understand different research methods (e.g. through discussions around research design). Engagement can also strengthen relationships between implementing organisations, academics and funders, which can increase trust in research findings and support future collaborations.

The study also shows that capacity building through SER doesn’t just benefit the partner/ implementing organisations- researchers and research organisations also benefit. For example, working closely with stakeholders can provide improved access to information, generate new ideas through increased interaction, and build institutional knowledge. More indirectly, SER can create a sense of a shared mission, and having a direct connection between your research and real-world impact can improve morale and motivation for researchers.

We believe the capacity building benefits of SER shouldn’t simply be seen as “positive externalities”. Instead, we should actively consider and design SER projects to deliver impact, both through their end products and the research process. We explore how various benefits of stakeholder-engaged research could be achieved in the two case studies below:

The Studies

In the spirit of representing views from different stakeholders, our studies come from two different sources to illustrate the use of SER methods across the space. Firstly, we use one of our projects conducted in collaboration with Animal Advocacy Africa (AA Africa), followed by some valuable research produced by Animal Alliance Asia (AA Asia). The main differences between the pieces were that:

The AA Africa project was focused on ‘market-entry’, while AA Asia was focused on consolidating and improving their role supporting animal advocates across the continent.

AA Africa was focused on Farmed Animal Welfare/ Vegan organisations, while AA Asia’s research includes all animal advocates

We (Good Growth) were involved in the AA Africa study, but had no direct involvement with the AA Asia work

Read on for details of both studies:

Study One: Asia Capacity Building Study (Animal Advocacy Africa)

In 2021, Animal Advocacy Africa were thinking of expanding their capacity building program to include parts of Asia. As both continents remain relatively neglected by international advocates and may face some similar challenges, AA-Africa believed that their model may also have worked effectively in the Asian context. They engaged us to better understand the internal challenges and bottlenecks faced by farmed animal welfare / vegan organisations in Asia. The main goals were:

Explore what capacity building actions/interventions are most needed to solve the challenges faced by organisations in the region

Assess whether Animal Advocacy Africa’s capacity building programme should be replicated in Asia

Methods

After conducting some desk research into publicly available reports and media interviews with advocates we engaged stakeholders directly with a research project using qualitative methods. Our research stages were comprised of:

Desk Research. We started by analysing publicly available reports from animal advocacy organisations, charity evaluation reports, and available media resources

Interviews. We then conducted semi-structured interviews with four regional capacity builders/grantmakers and six local organisations, followed by three informal chats/email interviews with additional regional and local organisations to identify the most important challenges.

Idea Generation. To address the challenges identified during our research, we developed some capacity building ideas based on these interviews.

Validation. We validated these ideas through a small-scale survey with local organisations.

Report. By synthesising the feedback from the interviews and the survey, we summarised the major challenges and needs of Asian advocates, and were able to recommend high-potential ideas for other capacity builders and donors to consider implementing or exploring in Asia.

What we learnt

We discovered that it isn’t easy working as an animal advocate in Asia, but that there are many ways that capacity building could help. Based on our interviews, we divided potential intervention areas into six separate categories, 1) HR, Finance and Communications, 2) Learning and Development, 3) Fundraising, 4) Hiring, 5) Research and 6) Individual Advocate Support. We then split these into specific interventions, which advocates were able to vote for in the survey.

The following charts indicate which areas the organisations surveyed said they would want support with:

Source: Animal Advocacy Africa Report (Unit = Number of organisations choosing an option)

Source: Animal Advocacy Africa Report

Firstly, most local groups said that they would benefit from direct, work-related training. Recognising the high impact of corporate and legal interventions, many respondents told us that training in corporate outreach best practices would be especially valuable, with public outreach campaign management and government-related work also seen as important. Ideas included providing effective and context-sensitive training in these areas through work exchanges, knowledge-sharing workshops, or with personal mentorship.

Next, groups struggled with the practical challenges of communications and operations. Coming up with an effective outreach strategy requires lots of organisational skills, as do the technical tasks of designing appealing social media posts or short videos. Operations represent a bottleneck in many organisations, as there are few available dedicated operations specialists. As such, a highly-recommended suggestion was to support Asian groups in this respect by providing discounted/sponsored or pro-bono outsourced services for communications (e.g. social media or design consultants) or operations.

Securing funding is almost always a challenge for local animal advocates. The organisations we interviewed were almost completely reliant on western funding sources, especially for specific farmed animal welfare and vegan advocacy work. This requires appealing to Western funders through grantmaking procedures, which sometimes involves language barriers and other communication issues. Advocates may also have to face potentially restrictive local laws around accepting foreign funding. Finally, as most organisations were relying on a limited set of foreign funding sources, organisations felt vulnerable and had limited opportunities for growth. As such, support with engaging new funding sources was proposed as a high-impact capacity building intervention. Solutions might include developing a local base of donors, or partnering with online platforms such as abillion or crowdfunding sites to develop a global small donor reach.

Although fewer organisations identified these as high-potential interventions, advocates also mentioned the need for locally-relevant data and research. For example, one local organisation expressed the need for additional funding to engage academia in local research related to animal welfare standards. They highlighted how this could provide more convincing arguments when speaking with industry and government stakeholders. The organisation also suggested that general market data, such as import/export numbers and regional success stories for high-welfare products, could support their prioritisation and communications.

Finally, hiring the right talent was seen as a problem. The budget for hiring animal advocacy staff in Asian countries is generally limited, and organisations struggle to provide the kind of salaries that would attract highly-skilled graduates from competitive fields. Sadly, the nonprofit sector in many Asian countries tends to be seen as a low-potential, low-salary career path, which, especially in the more competitive, achievement-focused cultures seen across parts of Asia, puts a lot of talented people off animal advocacy careers. Some solutions to these problems are offering professional development opportunities, considering more competitive salaries for certain roles, matching skilled volunteers and working with existing fellowship programs to offer early career opportunities to work in local organisations.

Something that was not explicitly identified as a capacity building intervention, but that came up in the interviews, was the merits of working with social movements outside of animal advocacy that could provide support for the Asian animal movement. As the number of dedicated animal advocates in each of these countries is likely to remain small, advocates pointed out the value of allying with other social movements, such as those involved in climate or sustainability activism, sustainability-related businesses, as well as motivated academics and researchers. Some of the successes from other local movements could be used to inspire creative solutions, and this process could play a key role in building an active advocacy movement in Asia.

Conclusions

Ultimately, our partners at Animal Advocacy Africa decided not to launch their capacity building program in Asia. This research project allowed them to realise that the needs of the broader African and Asian animal welfare movements were more distinct than expected, and that their strategy was less suited to the Asian movement. However, they have decided to make the study publicly available to inform advocates, capacity builders and funders of the exciting opportunities available to support the Asian advocacy movement to become larger and more effective in the years to come.

Lynn Tan, Co-founder of Animal Advocacy Africa said that the research: ”… directly guided/informed our internal decision making…[and] potentially saved us enormous amounts of time and helped us avoid making difficult-to-reverse actions”.

Check out the full report here.

Study Two: Animal Alliance Asia

Animal Alliance Asia is an organisation that focuses on supporting advocates in Asia. Their core mission is focused on building a more inclusive and effective animal movement from within Asia, with a strong emphasis on bringing together and empowering local animal advocates. They focus on delivering programmes like the Animal Advocacy Academy, Country Forums, and their annual Animal Advocacy Conference Asia to help educate, create networking opportunities necessary for collaboration, and provide support to individual advocates and organisations across the region. They are currently looking to introduce new programmes such as the Future Leaders Asia Summit, a regranting program and multiple Asia-specific research projects.

This particular example is an in-depth qualitative study based on the 2022 version of the annual country forums held by Animal Alliance Asia in 10 different countries. We’ve chosen to highlight it here as a creative example of engaging stakeholders in research, and the potential impact of such engagement.

Their goals of this study were to:

Support local organisations and advocates to reflect and improve on their advocacy by sharing the culturally-specific challenges, opportunities and solutions discussed in the forums;

Facilitate capacity-building organisations in Asia to identify areas where they can support local animal advocates; and;

Assist funders who are interested in supporting animal advocacy in Asia to better understand the needs of local organisations and initiatives and maximise the effectiveness in their fund allocations.

Methods

In 2022, Animal Alliance Asia conducted a series of forums for advocates across Asia in order to build relationships with Local Animal Advocates (LAAs) and explore culturally specific challenges, opportunities and solutions. Ten Asian countries participated, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam, each with its own forum sessions. These forum sessions were semi-structured discussions using open and closed questions, and were designed by AA Asia’s internal team. Country coordinators were encouraged to recruit participants, facilitate discussions and conduct online or offline forums, depending on the country-specific circumstances. Discussions were conducted in local languages and later translated into English. The findings were filled into a standardised form by the country coordinators, and additional desk research and observations were used to complement the data, then a research assistant compiled and analysed the findings.

The motivation for holding the forums was “to listen to the voices of advocates and better understand their experiences on the ground before determining “what works best in each country”.

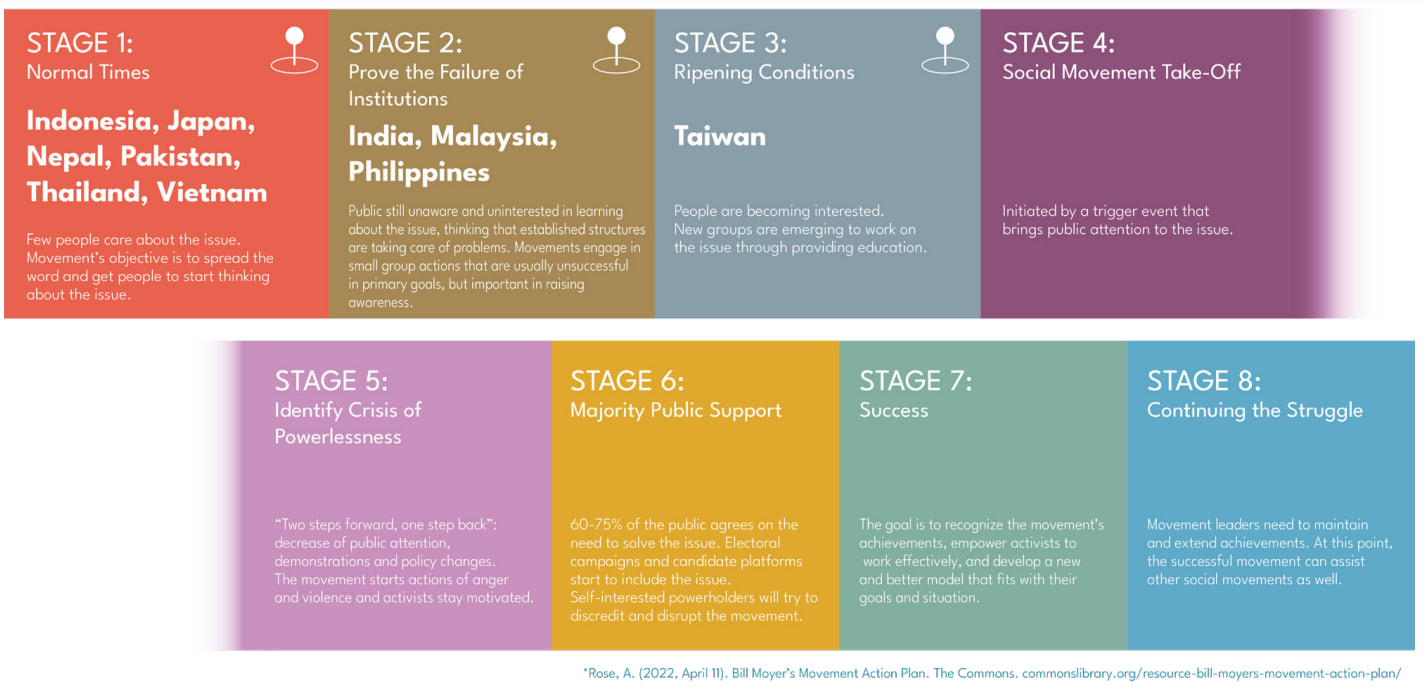

During these forums, qualitative data was collected for a cross-country analysis. As part of in-depth discussions, country coordinators were also asked to assess the progress of the animal advocacy movement in their country according to Bill Moyer’s Movement Action Plan (MAP) framework. The MAP identifies 8 stages of a social movement, with 1 indicating that the movement is in the beginning stage, and 8 being that the movement has tentatively succeeded in its goals.

These methods are interesting for a couple of reasons—firstly, while the methods were open-ended and qualitative, AA Asia came into the study with an established theoretical framework for movement growth, working under the assumptions that social movements tend to follow broadly similar trajectories. Second, the researchers used interactive forums instead of focus groups/ interviews, which are more commonly used qualitative methods.

Findings

In terms of the MAP framework, the research confirmed that the animal welfare movement is still at a nascent stage in most of Asia. Only Taiwan was identified as somewhere where ‘conditions were ripening’ for the animal advocacy movement, while other countries were in the earlier stages. This provides an interesting update as to how we want to look at building the movement across Asia.

Some of the bottlenecks and challenges identified in the study were similar to those we identified in the previously mentioned study, providing some support for the claims we had made.

For example, LAAs (Local Animal Advocates) across ten countries reported gaps in the animal advocacy space regarding country-specific knowledge, advocacy training, and, most significantly, funding. Funding gaps make it difficult to create programs and paid opportunities for LAAs, which in turn is an obstacle to LAAs attempting to pursue animal advocacy as their career path. With this lack of training opportunities, LAAs rarely had any formal training in animal advocacy, and instead had to learn their skills in the field. LAAs emphasised the need for workshops and training to build skills such as leadership, nonprofit management, fundraising, and communication.

There were also some interesting insights that we hadn’t identified:

Advocates from many countries expressed the desire for a “middle entity” or mediator to facilitate collaboration between organisations, or the sharing of resources.

There is a significant lack of country-specific data and research on local animal advocacy tactics, animal welfare violations, animal agriculture systems, and levels of animal abuse.

As well as these insights into capacity building, the study also provided some insights into the struggles faced on the ground by advocates, and the kind of advocacy work that would be valuable in specific countries.

Friendly and considerate, rather than antagonistic, methods were predicted to be the most effective tactic by advocates. Although this hasn’t been explicitly tested in these regions, advocates report more successful corporate and awareness-raising campaigns when they target audience sympathy rather than guilt.

When advocates were asked which approaches they believed to be effective in their specific context, most groups emphasised the importance of creating public awareness. This suggests that approaches that may not directly result in a high number of animals saved, such as active rescue work, are seen as contributing significant value through the indirect impact of promoting visibility. These efforts are seen as potentially contributing to community growth, enabling organisations to garner local support, and enhancing fundraising opportunities.

Attempts to influence policy/ legal reform will vary greatly from countries with effective political/ legal systems (Japan) to those with struggling legal systems (Thailand)

Islamic countries in particular require nuanced approaches that account for halal dietary norms, and consideration of different stakeholders, such as religious groups

Finally, there were some interesting takeaways from the relationship between funders and local advocates. Funding usually comes with the pressure to focus on specific areas chosen by foreign funders as a prerequisite condition, which generally doesn’t allow for the input of local advocates. This created challenges for advocates, who were often discouraged from pursuing the interventions that they considered to be more practical or effective in the context.

Limitations

There are inherent limitations to this kind of research.

With the AA Africa study, we had a moderate response rate (8 out of 18 target organisations responded to the survey), a limited sample size, and we weren’t able to conduct studies in local languages, meaning that we selected for organisations and countries with some English proficiency. To compensate for this, we also reached out to regional organisations first to provide a better overview of issues across Asia, before diving into some local issues. Therefore the study was more likely to capture broad regional trends, than details with regards to all the specific countries and sub-cause areas where advocates were operating.

Many of our findings are still at a preliminary insight stage, and need to be tested more rigorously. With AA-Africa, we obtained enough information to target capacity building for the organisations in question, by testing key findings with a small quantitative survey. However, due to the small sample size, external validity is likely to be limited. With both these studies there are some important actionable insights, but there is also a wide range of hypotheses that should be tested more rigorously (see here for a list).

Discussion

There are many interventions that funders and international advocates can use to support Asian advocacy groups in tackling community-building challenges. Providing training, fellowships, work exchanges, and pro-bono support for Asian animal organisations are particularly promising. More ambitiously, taking a systematic approach to building an international ecosystem of support for Asian organisations would better allow us to combine the experience and resources of the international movement with local advocates’ understanding of their countries’ distinctive needs.

These are likely to be high impact interventions, largely because building the capacity of the Asian advocacy movement has the potential to be self-reinforcing. Attracting more skilled people with improved resources leads to advocacy organisations generating better, more fundable ideas, which then allows them to provide evidence of success and build their profile, thus allowing them to attract attention from both local stakeholders and international funders. This process could potentially be a virtuous cycle, where increasing the capacity of a local advocacy movements can be self-perpetuating.

Conclusion—What have we learned from (3 years of) doing SER in Asia?

This post and the previous post have illustrated our experiences using stakeholder-engaged research methods in Asia over the last few years, and we’ll finish this post with a quick overview of some of our learnings.

Working across Boundaries

Firstly, we’ve learned a few different things about working across cultural boundaries that can inform our perspective on animal welfare interventions:

We’ve found that local and international animal advocates have different perspectives on what might work, and we typically have high uncertainty about who might be right in a given context. For example, local advocates have informed us that corporate outreach and pressure campaigns, which are often supported by international advocates, may be ineffective and create backlash in certain Asian contexts. On the other hand, smaller-scale interventions, such as direct action (rescues) are sometimes seen by local advocates as playing a role in generating publicity, changing minds and building grassroots support. One of our future goals is to improve communication between international and local groups to test which of these viewpoints is the more accurate, and improve prioritisation based on this.

In the China studies, engaging with consumers has challenged our views on meat reduction and alternative proteins. The array of associations people link to meat-alternatives in China: “mystery” meat and “zombie” meat with suspicious origins, soy replacements high in additives, and mock meat served in Buddhist temples, call for very different messaging around protein alternatives. We also found that the differences between modern plant-based meat and mock meat are rarely well understood by regular consumers in China or elsewhere in Asia, which adds an additional challenge to the development of localised marketing strategies.

We also learnt from our focus groups that older Chinese consumers (grandparents) seem particularly susceptible to meat reduction messaging for health reasons, and were also sympathetic towards welfare messaging. This was a surprising finding that goes against the more common view, held by advocates we’d spoken to, that older people in China are less susceptible to change. We also noted that grandparents have a role in food shopping and preparation for many Chinese families, suggesting that they may have an outsized influence on a family’s diet. Our more recent research has found this to have resonance across multiple Asian contexts, which could inform different outreach strategies for the advocacy movement across Asia.

These are examples of how our initial assumptions about working in new markets can be wrong or incomplete- this is especially true when assumptions are made by international actors with little experience in diverse contexts. Of course, locally-based advocates can also be wrong, pointing to the need for more engaged research with multiple stakeholders. These findings can allow us and our partners to work better across national and cultural boundaries, to make better decisions and avoid costly mistakes.

As well as these national and cultural boundaries, we’ve also noted the challenges of working across epistemological boundaries—in particular, the gap between people grounded in the EA movement, and local advocates working under a different set of ideas or assumptions.

The two studies in this article both used qualitative approaches to address similar questions, but had slightly different epistemological approaches. Our approach (with AA Africa) was more positivist—we used mixed-methods approaches to generate and test hypotheses for effective capacity building interventions—while AA Asia took more of an advocate-led and justice-focused approach to address problems faced by local animal advocacy movements.

These approaches aren’t necessarily contradictory—the practical considerations that come from the social justice approach, such as prioritising respect for local animal advocates, while acknowledging power imbalances in the field, shouldn’t contradict principles of transparency, evidence-based theories of change, and effectiveness. However, this raises interesting issues regarding working more closely with organisations that have different values, or views about what is important, and about how knowledge should be created.

While EA organisations tend to share a common epistemological framework, this framework is not universally shared by most of the stakeholders any EA-aligned organisation is likely to work with. But as long as preventing animal suffering is a shared goal, navigating these challenges provides increased opportunities to build a more resilient and effective movement.

Changing Strategies through Stakeholder-Engaged Research

We’ve observed that stakeholders in international animal advocacy, including our partners, have updated their approaches to stakeholder engaged research, and increased consideration of stakeholder-engaged methods is starting to affect the way that organisations develop their strategies.

A direct example of SER affecting strategies is the extent to which AA Asia and ourselves have made some changes based partly on the findings mentioned in this forum post. AA Asia have launched a new ReRoot Asia regranting fund to address funding challenges that local advocates identified in the forums. At Good Growth, two of our potential upcoming projects respond to some of the challenges identified in this research. The first involves satisfying the need for improved information and data with an online Asia data library, while the second involves using user research and country workshops to tackle hiring challenges, and effectively grow and retain animal advocacy talent in Asia.

Through working in this space, we’ve also noted that stakeholders in international animal advocacy are increasingly identifying the need for more engaged contextual research. Funders and larger advocacy organisations are identifying challenges that are more difficult to address with more straightforward desk-based or survey research, and we’ve noticed an increased demand for more engaged methodologies. On the advocate side, while disseminating our research, multiple local animal advocacy organisations we’ve engaged with have reached out to us to express their interest in learning about SER methods, while others have asked how they might be able to build their research capacity and/or conduct similar research.

Process and Product—Different ways that research can have an impact

Most organisations go into a research project assuming that the benefits will accrue at the end of the research, when ideas are published and disseminated to stakeholders. However, as we’ve explored more ways of conducting SER, involving more stakeholders at different stages, we’ve identified more benefits elsewhere in the research process. These have involved developing connections, empowering advocates to better use their local knowledge, and capacity-building. This has led to further collaboration with local groups, increasing their contribution to projects and potentially improving their alignment with our goals.

This increased collaboration and partnership has led us to think about two different ways that research can have an impact, which can be categorised into product and process outcomes.

The product outcomes are those that result directly from the research outputs—a physical product, a new strategy or intervention, or a set of insights. Engaging stakeholders in product-focused research can improve these outcomes by generating better, more relevant and/or innovative research products, resulting in more usage of the research and improved decision-making. In our case, conducting engaged research with multiple stakeholders on the AA Africa project was intended to improve the quality of our insights, and therefore help the organisation make better strategic decisions.

On the other hand, the process of participating in research can also produce valuable outcomes. For example, the research literacy of stakeholders might be improved through a ‘learning through doing’ framework or, as in the case of AA Asia’s forums, the research process can facilitate relationship-building between stakeholders, alongside the sharing of knowledge, experience, problems and solutions. Research participation can also empower groups who don’t usually have a say in research decisions to contribute. Another benefit from a shared research process can also be psychological or relational—co-creating research can change the behaviour and attitudes of the participating individuals and groups. This could be a process of cultivating greater value alignment or building links between less aligned communities. These aspects of research process can lay the foundation for collaboration, and potentially lead to improved research design in the future.

Our main update here has been through becoming more cognisant of the benefits accrued through the process of research, and to increasingly consider these benefits while designing research. Better identifying the influence of engagement in both the product and process of research is something that we’re hoping to focus on in the near future.

Trade-Offs and Uncertainties

As a small research organisation with multiple obligations to funders and partners, we’re very aware that engaging stakeholders takes up time and resources. While an online survey can be designed, tested and conducted within a few weeks if necessary, more engaged research methods take longer, while cross-cultural communication can also be challenging and frustrating.

We haven’t seen a good cost-effectiveness analysis looking at the trade-offs to increased levels of engagement. It seems likely that the benefits from increasing from zero engagement to some engagement with stakeholders- in particular, significantly decreasing the downside risks when working in new cultural contexts- will outweigh the costs. However, moving from moderately- to highly-engaged research methodologies is likely to entail larger trade-offs, which we hope to look at in more detail in the future.

Developing a Better Model of Impact

Considering stakeholder-engaged methods has helped us to reconsider how research leads to impact. We were previously thinking in terms of a more simplistic, linear model where we use rigorous methods to produce reliable evidence, which leads to evidence-based interventions, which leads to impact. However, this model misses out some important steps towards reaching our goals, and doesn’t capture many of the ways by which impact is created through research.

A lot of our research has depended on developing new insights into animal advocacy and alternative proteins in Asia. After uncovering an insight that stakeholders are able to use, we have to ask: “What do we do with this?”. We can publish it in a report or forum post and hope that someone chooses to act upon it. Or we can get in touch with particular stakeholders to start the process of converting insights into interventions or future behaviour, often through workshops, presentations and other events across Asia.

But we’re increasingly seeing ways in which this kind of dissemination can be sub-optimal, and results in a lack of integration between research and action. When implementers (advocates in our case) and researchers are working separately, implementers don’t always have access to the most up-to-date research that could inform their interventions, while researchers don’t always have access to implementers who could transform their research into action when they design and conduct their research.

An promising approach to address this is co-creation, where stakeholders are actively engaged in identifying research questions, interpreting insights and brainstorming new solutions. Here, partners work together to integrate insights into the decision making process of the implementers, and leverage the contextual knowledge of the implementing/ on the ground partner to develop new strategies and solutions.

In fact, we’re going to try implementing this idea through a series of co-creation workshops later this year, in collaboration with several animal-related conferences. Our goal is to take 3 years worth of research insights and work with local stakeholders to produce novel, context-sensitive solutions to improve the lives of animals. Our vision is to build a Research-to-Action lab, where we can systematically facilitate the process of translating research into effective actions for animals. We are currently seeking partners and funders for this work, so please get in touch at team@goodgrowth.io if you’re interested in participating or funding this initiative.

- ^

Calculated based on these grants. Total funding was USD $45.1 million for farmed animal welfare from 2016 to Jan 2023. I calculated that $8-12 million went to organisations that could have been classified as “local”. We get slightly different figures when we class organisations such as Sinergia, a Global-South focused advocacy organisation founded in Brazil, as local/ international.

Initial thoughts: Very much needed! Strong upvote. Also found the AA Africa study of Asia quite useful. Context sensitive country based research is the need of the hour. And once we have the problems/solutions, I also feel we currently fall short on the ability of operationalising the solutions within orga. Looking forward to more SER work in Animal advocacy especially in global South.