Why care about human longevity?

Aren’t programmable drugs for future pandemics more pressing? What about childhood cancers—or preventing existential risks to extend our longevity as a species? Aren’t humans a burden on the planet? Doesn’t science advance one funeral at a time?

Why prioritize human life?

I’d especially welcome criticism on these thoughts from folks not interested in human longevity. If your priority as a human being isn’t to improve healthcare or to reduce catastrophic/existential risks, what is it? Why?

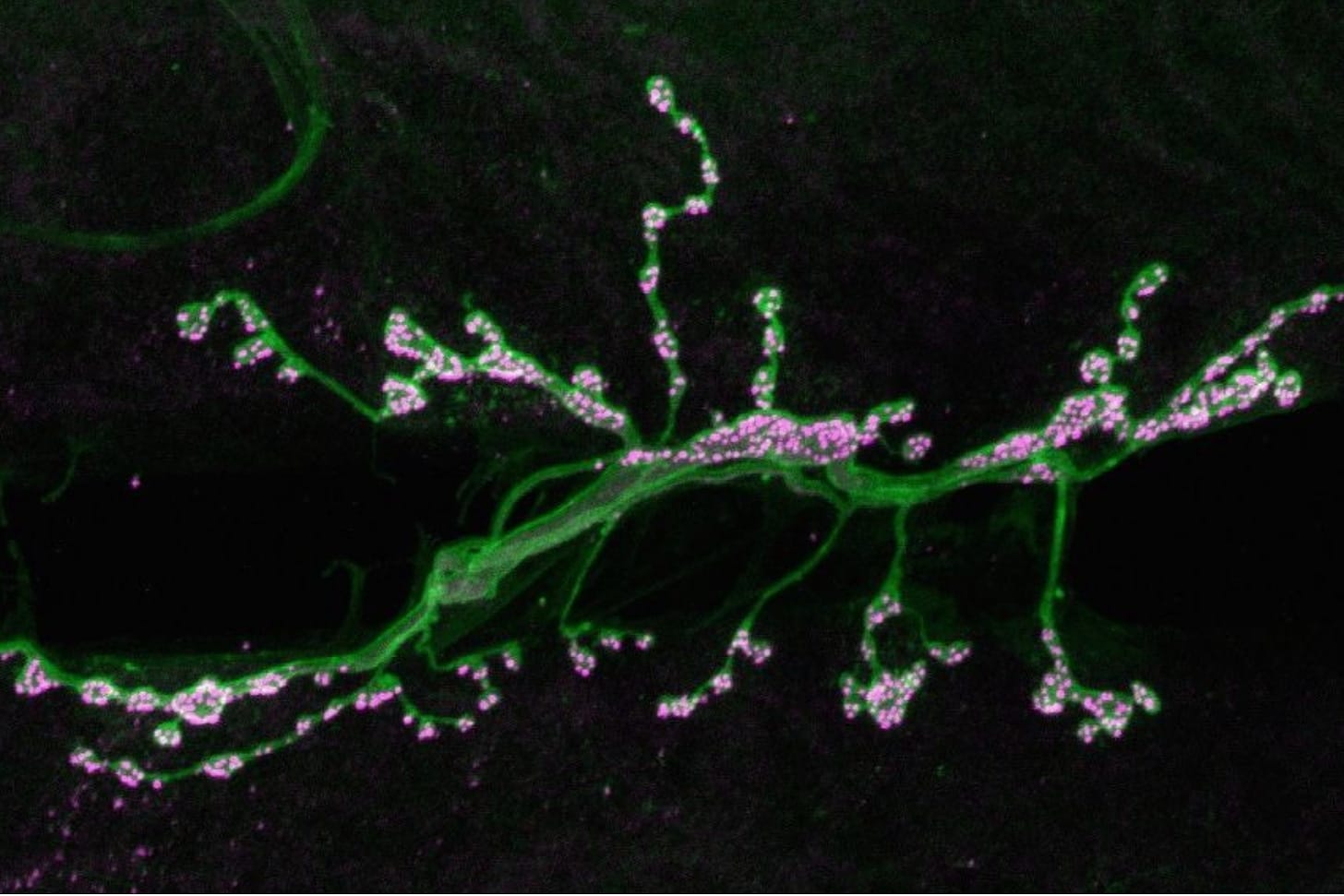

“Strengthening connections between neurons”—Troy Littleton

“We are going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones. Most people are never going to die because they are never going to be born. Those unborn ghosts include greater poets than Keats, scientists greater than Newton. We know this because the set of possible people allowed by our DNA so massively exceeds the set of actual people. In the teeth of these stupefying odds it is you and I, in our ordinariness, that are here.”

Richard Dawkins, Unweaving the Rainbow

Imagine the year is 1950, early spring. Heart transplants are the stuff of repugnant fiction. Birth control is yet to be tested in humans, and no woman on Earth has the choice of controlling her innate biology. By the year’s end, smallpox will take some 5 million lives — maybe more. In developing countries, a tooth infection is deadly. Everywhere, a cancer diagnosis is almost as likely to be managed by a doctor as it is by a priest.

In 2024, most of us accept some enhancements to our natural life course, like polio vaccines. We do not refuse antibiotics just because they unnaturally add some 23 years to our life expectancy. And heart transplants are no longer heretical, but the stuff of strait-laced, good old medicine.

Still, the idea of extending the human lifespan beyond its unchanged maximum of (allegedly) 122 lies somewhere between avant-garde and fringe.

Why?

One explanation is that most people, when they hear “life extension,” think of the 20th century — when we doubled our average life years without a corresponding increase in healthy life. Another is that improving the biology of aging — so that we get to live longer without age-related frailty and disease — is technically difficult.

In a 1993 study, changing one gene (daf-2, a pathway humans share) in C. elegans worms doubled their lifespan. Changing one additional gene (rsks-1) resulted in a five-fold lifespan increase—the equivalent of a 400-year-old human. But technologies like genome engineering for polygenic conditions may be decades away from safety. And promising approaches like replacing aged cells, organs, and tissues will be difficult to deploy at scale.

To date, no single intervention has been proven to reverse biological aging or to extend the maximum lifespan in humans. Clinical trials for multiple diseases—let alone health & lifespan—are costly, lengthy, and difficult to translate between species. As a result, the effects of existing therapeutics on human aging remain largely speculative, and a long list of bottlenecks in the field remains underfunded.

But funding often precedes the technically ambitious results we desire.

This has so far been the case for AI alignment and neurodegenerative diseases, and it was the case for COVID vaccines.

In 2024, the young science of aging remains the subject of often repulsive fiction — and receives only about 1% of all National Institutes of Health funds: about 8 times less than research on neurodegenerative diseases, even though they’re just one of the several things that go awry with age.

On the private investment front, aging research makes up roughly 3% of all venture capital in biotechnology. And commercial incentives have so far mostly optimized for unproven supplements, imprecise biological-age apps, or unsafe experimental therapies and cosmetics.

Today, the longevity field largely places its bets on 1) a small roster of scientists achieving a breakthrough, and 2) technological convergence (e.g. AI) spontaneously arriving at a health-&-lifespan wonder drug.

This lack of funding for serious research on the biology of aging can only be partly explained by the snake-oil “cures” that continue to plague the longevity field. A less circular reason why we haven’t improved how we age over several millennia is that humans just don’t buy the idea that improving the biology of aging is a noble and pressing causes to begin with.

In a world with non-infinite resources, isn’t it more noble and pressing to treat the already sick? Aren’t, say, programmable drugs for future pandemics more pressing? Given the climate crisis, shouldn’t we be reducing the number of humans on Earth? If aging drugs could delay up to 90% of all deaths, is this the world we’d want to engineer? Doesn’t science advance, as perhaps every STEM student on Earth has learned, one funeral at a time?

I’m often asked why, as a bioethicist, I’ve joined a team of people pushing the frontiers of science to compress the timeline for technologies that extend the human lifespan.

My answer is simple: because human life is what I value most — above all other things.

Progress, as I will try to show you, doesn’t magically unfold when funerals take place. Most often, it is architected by the living.

If we do our jobs right, we’re almost sure to live through generations of poets greater than Keats, scientists greater than Newton. We may unlock the unborn ghosts that lie already within each of us — with lives now too short and overwhelmed with grief and pre-abundance tradeoffs and disease, and bodies too brittle to live up to our infinite dreams as a finite, dainty species.

Why prioritize human life?

To start with, because it’s the honest answer.

Modern governments prioritize fire stations over witch trials; they sooner fund vaccines to stop public health crises than funeral homes; and they even build safe roads and mandate building codes and enforce laws like wearing seatbelts because the loss of human lives is socially expensive.

For every human death, an average 9 humans are negatively impacted in profound ways. Grief costs the U.S. alone an estimated $75 billion a year in productivity losses. Unpaid caretakers of older adults in declining health in the U.S. add up to a combined lost income of $522 billion every year.

Conversely, for every 1% increase in population growth, a 3 - 4% increase in personal abundance can be tracked, measured by access to goods like food or services like transportation.

Economic Growth Over the Very Long Run—Chad Jones

Of course, governments do not fund our wellbeing just because it can improve our federal budget. If that were the case, states may well incentivize for their populations to smoke and die quickly and young, as a short-termist path to saving trillions of dollars on Social Security & Medicare.

But it’s worth noting that people and governments didn’t always appreciate human life as valuable.

In Ancient Rome, humans gathered around gleefully to watch as other low-status humans were tortured and killed. Codes like the Hammurabi existed since 1750 BC — but the value of life was far from egalitarian. Most humans, most of the time, were perceived as fungible means.

This can still be the case, but we have made much progress.

The Enlightenment can be credited with highlighting the possibility that all humans, of all classes, could be valuable. As one economist put it:

“It became obvious for the first time that wealth could grow, that classes could be fluid, that life could be extended, that the population could grow and grow, that we could progress together. With that evidence [from the late Middle Ages] came the entrenchment of a commitment to individual rights and a longing for universal emancipation and the good life for all. A related commitment emerged to the cause of medical science not just to help the few but to improve the whole lot of humanity.”

It’s been a lucky truth that human brains have been a major cause of economic growth and progress. This truth led (partly) to the creation of welfare states, and to the once-idealistic notion that all lives should be valued equally, since classes can be fluid.

But this view of people “as human capital fully replaceable first by immigration, and then eventually by technology” has its shortcomings.

The project of ensuring Homo Sapiens remains relevant — in a world filled with sprightly, artsy, and never-tired robots — will demand extreme honesty from us as a species. The rise of independently intelligent machines may challenge our assumptions on why we ought to value human life, when anything we can do, a robot will likely be able to do better, and when any economic output linked to unaided biological brains may become obsolete.

We can work towards a biosingularity where we evolve together with machines. But for humans to make it through this first half of the third millennium with a continued sense of value, we’ll also need to intently work towards a new type of self-worth.

In 2024, many humans continue to derive their worth from their production value. One 21st-century farmer, engineer, or baker can produce more resources than she consumes in her lifetime. Yet in the coming decades, we’ll need to bolster the idea that human life — regardless of its output — has intrinsic worth.

It may be the case that we can’t rationally explain why we ought to prioritize human life over, say, other conscious animals or machines without veering into what philosophers have called infinite regress. The best explanation available to our primate brains may be “we ought to value human life because it’s what is best for us.”

This may be an unsatisfying answer. But if we found ourselves paralyzed by this justification, unable to decide whether our hospital beds should prioritize conscious humans over conscious mice, the loved ones of the humans hypothetically lost in our deliberation would be rightly outraged.

Nearly all noble things a human being can do — from building climate technologies to helping a stranger cross the street to engineering rockets that traverse the stars — are done to celebrate, improve, or protect human life.

Sometimes, we’ll grant secondary moral status to non-human lives that seem to function like ours. And I happen to think it’s critical we admit this hierarchy — just as it’s wise to assume that if superintelligent machines aren’t aligned to our brains, to serve our goals, they may well treat us as we do other less intelligent life forms. (Not out of malice, but mere competence.)

We should — and I trust, will — work towards a future with non-scarce resources, where human and non-human lives can co-exist with equal rights.

Yet in the near term, even those of us who don’t eat other conscious animals (I don’t) generally support their use in clinical findings to save human lives — even if the long-term goal should be to move towards preclinical development on never-before-conscious subjects through methodologies like organs-on-chips or computer models.

With some isolated exceptions to this rule (e.g. terrorist or ecocentric groups), our chief aim as a civilization — the occupation of some of the brightest people on Earth, who work on goals like nuclear policy and climate innovation and AI alignment — can now be summarized as to nurture and protect human life.

This is no small achievement.

But there’s a way in which this is, more than a feat, a feature. We value human life because it’s what we’re biologically wired to value. Because life is what enables each possible subjective experience we can have — from enjoying a late-summer breeze to building history-changing companies to caressing a beloved pet.

It may be time we reconcile this evolutionary thirst for life with the Enlightenment view of human lives as inherently worthy of investment.

Why aging research?

There’ll be no single day on the calendar of Homo Sapiens when we finally engineer “longevity.”

If there were, it would have been when the first hominid attempted to postpone their death or suffering by some non-innate means; or when the first single-cell organism sought collective life in the hopes of improving its odds of survival.

If we look closely, just about all of medicine is designed to extend life or diminish suffering.

Health is only occasionally the goal of medicine. Palliative care aims to make end-of-life less painful. Resuscitation techniques (like defibrillation or CPR) and a good deal of drugs (like blood thinners or statins) aim to extend life.

The same is true of aging research, whose promise isn’t to extend life lived with zero disabilities — health and youth are discrete processes, even if they strongly correlate — but to prolong functional, active, livable life. (Some bioethicists have argued all lives are livable; others that we should not live past the age of 75; and the right answer is probably “it’s up to each human to decide.”)

Our goal, as it has been written before, should be to make aging drugs boring. (Think safer and more effective versions of ozempic, or rapamycin.) To make life-saving interventions available — like neuron transplants or therapies to restructure the extracellular matrix — and then have patients decide whether or not to adhere to them. And to enhance our biopreservation methods so that pausing life for extended periods of time (longer than the current lull between life and death for, say, patients suffering from cardiac arrest) becomes routine medicine.

Aging research is one way to extend and improve human life. But it’s one vastly overlooked way.

In the past few decades, the allocation of resources to “Global-South diseases” has been a growing moral trend. The Global Fund, for instance, “cut the combined death rate from AIDS, TB, and malaria by more than half, saving 59 million lives [in 20 years].” Space exploration and AI alignment also promise to more effectively extend our longevity as a species.

From a total-utilitarian standpoint, simply creating more working-age humans would solve many of our economic problems. But this solution, even if its timeline could be compressed — which it cannot, since newborns don’t work, and they one day grow old — overlooks the non-fungible value of existing human lives.

The world is aging — and this means the disease burden is shifting, in the Global North and South.

In Brazil, where I come from, non-communicable diseases now make up 75% of all deaths. By 2050, 80% of all older adults on Earth will live in low- to middle-income countries.

Non-communicable diseases in Brazil

Knowing what we do for certain, given no hypotheticals — that some 50 million age-related deaths happen every year, like clockwork, causing incalculable suffering in the Global North and South — drugs and tools designed to improve biological aging could save more lives in the coming decade than any other neglected drug or cosmic expedition.

Yes, an asteroid could hit the Earth and make a focus on individual longevity seem vain. But if we compress the timeline for aging drugs, we’ll have more resources and talent to engineer solutions that extend our longevity as a species.

And while the future may be sufficiently abundant that we get to divorce ourselves from economic datasets, the coming years will demand critical tradeoffs on how we allocate scarce resources.

Rounded estimates from the Congressional Budget Office

In just 11 years — between 2018 and 2029 — the U.S. mandatory spending on Social Security and Medicare will more than double, from $1.3 trillion to $2.7 trillion per year.

In the coming decade, safe and effective interventions for biological aging could allow us to reallocate trillions of dollars now projected for the social and medical care of adults aged 65 and older towards other noble causes — like pandemic preparedness or lowering infant mortality.

Indeed, biological aging is a neglected factor in childhood cancers (where patients experience premature aging), and in several communicable diseases.

The COVID death rate for people under 40, for instance, was around 0.2%.

COVID Death Toll—Vox

As Operation Warp Speed has shown, time alone is a deceitful metric when it comes to the advancement of fundamental science.

Market incentives aren’t by default aligned to what is best for us as a species. But with enough public and philanthropic funds, we can align them.

We can develop age-improving therapeutics — eventually, available to all — while building history’s most profitable life sciences companies.

We can unveil the principles of intelligence while solving Alzheimer’s.

And we can profitably accelerate technologies like brain interfaces and modeling to ensure the future of humanity remains contingent on and aligned to human minds.

The unifying theme of The Amaranth Letters will be that human life is rare; mostly evolved to celebrate, improve, and protect itself; and that human brains and aspirations are, more often than not, deeply good.

I hope you’ll join us in brainstorming how we can best use our primate brains to create more, better, and safer life.

Raiany Romanni is a Policy and Ethics researcher at the Amaranth Foundation. She is writing a book on the moral underpinnings and socio-economic implications of life extension.

Acknowledgments: Joanne Peng, Alex Colville, Rohan Krajeski, Aaron Cravens, James Fickel (& many others!)

Executive summary: Prioritizing research into extending the human lifespan is justified because human life has intrinsic value, and aging interventions could save more lives and resources in the near future than other causes.

Key points:

Historically, human life was not always valued intrinsically, but the Enlightenment promoted the idea that all human lives have worth.

In the face of AI and machines, humans will need to bolster the belief in the intrinsic value of human life regardless of economic output.

Most of medicine and human endeavors aim to extend life and reduce suffering, and aging research is an overlooked way to achieve this.

Aging is a growing issue globally, and interventions to improve biological aging could save trillions in healthcare costs and reallocate resources to other pressing issues.

With enough funding, anti-aging therapeutics can be developed while building profitable life sciences companies and ensuring humanity’s future remains aligned with human minds.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Personally, I am interested in longevity and I think governments (and other groups, although perhaps not EA grantmakers) should be funding more aging research. Nevertheless, some criticism!

I think there are a lot of reasonable life goals other than improving healthcare or reducing x-risks. These things are indeed big, underrated threats to human life. But the reason why human life is so worthwhile and in need of protection, is because life is full of good experiences. So, trying to create more good experiences (and conversely, minimize suffering / pain / sorrow / boredom etc) is also clearly a good thing to do. “Create good experiences” covers a lot of things, from mundane stuff like running a restaurant that makes tasty food or developing a fun videogame, to political crusades to reduce animal suffering or make things better in developing countries or prevent wars and recessions or etc, to anti-aging-like moonshot tech projects like eliminating suffering using genetic engineering or trying to build Neuralink-style brain-computer interfaces or etc. Basically, I think the Bryan Johnson style “the zeroth rule is don’t-die” messaging where antiaging becomes effectively the only thing worth caring about, is reductive and will probably seem off-putting to many people. (Even though, personally, I totally see where you are coming from and consider longevity/health a key personal priority.)

This post bounces around somewhat confusingly among a few different justifications for / defenses of aging research. I think this post (or future posts) would be more helpful if it had a more explicit structure, acknowledging that there are many reasons one could be skeptical of aging research. Here is an example outline:

Some people don’t understand transhumanist values at all, and think that death is essentially good because “death gives life meaning’ or etc silliness.

Other people will kinda-sorta agree that death is bad, but also feel uncomfortable about the idea of extending lifespans—people are often kinda confused about their own feelings/opinions here simply because they haven’t thought much about it.

Some people totally get that death is bad, insofar as they personally would enjoy living much longer, but they don’t think that solving aging would be good from an overall societal perspective.

Some people think that a world of extended longevity would have various bad qualities that would mean the cure for aging is worse than the disease—overpopulation, or stagnant governments/culture (including perpetually stable dictatorships), or just a bunch of dependent old people putting an unsustainable burden on a small number of young workers, or conversely that if people never got to retire this would literally be a fate worse than death. (I think these ideas are mostly silly, but they are common objections. Also, I do think it would be valuable to try and explore/predict what a world of enhanced longevity would look like in more detail, in terms of the impact on culture / economy / governance / geopolitics / etc. Yes, the common objections are dumb, and minor drawbacks like overpopulation shouldn’t overshadow the immense win of curing aging. But I would still be very curious to know what a world of extended longevity would look like—which problems would indeed get worse, and which would actually get better?)

Most of this category of objections is just vague vibes, but a subcategory here is people actually running the numbers and worrying that an increase in elderly people will bankrupt Medicare, or whatever—this is why, when trying to influence policy and public research funding decisions, I think it’s helpful to address this by pointing out that slowing aging (rather than treating disease) would actually be positive for government budgets and the economy, as you do in the post. (Even though in the grand scheme of things, it’s a little absurd to be worried about whether triuphing over death will have a positive or negative effect on some CBO score, as if that should be the deciding factor of whether to cure aging!!)

Other people seem to think that curing death would be morally neutral from an external top-down perspective—if in 2024 there are 8 billion happy people, and in 2100 there are 8 billion happy people, does it really matter whether it’s the same people or new ones? Maybe the happiness is all that counts. (I have a hard time understanding where people are coming from when they seem to sincerely believe this 100%, but lots of philosophically-minded people feel this way, including many utilitarian EA types.) More plausibly, people won’t be 100% committed to this viewpoint, but they’ll still feel that aging and death is, in some sense, less of an ongoing catastrophe from a top-down civilization-wide perspective than it is for the individuals making up that civilization. (I understand and share this view.)

Some people agree that solving aging would be great for both individuals and society, but they just don’t think that it’s tractable to work on aging. IMO this has been the correct opinion for the vast majority of human history, from 10,000 B.C. up until, idk, 2005 or something? So I don’t blame people for failing to notice that maybe, possibly, we are finally starting to make some progress on aging after all. (Imagine if I wrote a post arguing for human expansion to other star systems, and eventually throughout the galaxy, and made lots of soaring rhetorical points about how this is basically the ultimate purpose of human civilization. In a certain sense this is true, but also we obviously lack the technology to send colony-ships to even the nearest stars, so what’s the point of trying to convince people who think civilization should stay centered on the Earth?)

I really like the idea of ending aging, so I get excited about various bits of supposed progress (rapamycin? senescent cell therapy? idk). Many people don’t even know about these small promising signs (eg the ongoing mouse longevity study).

Some people know about those small promising signs, but still feel uncertain whether these current ideas will pan out into real benefits for healthy human lifespans. Reasonable IMO.

Even supposing that something like rapamycin, or some other random drug, indeed extends lifespan by 15% or something—that would be great, but what does that tell me about the likelihood that humanity will be able to consistently come up with OTHER, bigger longevity wins? It is a small positive update, but IMO there is potentially a lot of space between “we tried 10,000 random drugs and found one that slows the progression of alzheimers!” and “we now understand how alzheimers works and have developed a cure”. Might be the same situation with aging. So, even getting some small wins doesn’t necessarily mean that the idea of “curing aging” is tractable, especially if we are operating without much of a theory of how aging works. (Seems plausible to me that humanity might be able to solve, like, 3 of the 5 major causes of aging, and lifespan goes up 25%, but then the other 2 are either impossible to fix for fundamental biological reasons, or we never manage to figure them out.)

A lot of people who appear to be in the “death is good” / “death isn’t a societal problem, just an individual problem” categories above, would actually change their tune pretty quickly if they started believing that making progress on longevity was actually tractable. So I think the tractability objections are actually more important to address than it seems, and the earlier stuff about changing hearts and minds on the philosophical questions is actually less important.

Probably instead of one giant comprehensive mega-post addressing all possible objections, you should tackle each area in its own more bite-sized post—to be fancy, maybe you could explicitly link these together in a structured way, like Holden Karnofsky’s “Most Important Century” blog posts.

I don’t really know anything about medicine or drug development, so I can’t give a very detailed breakdown of potential tractability objections, and indeed I personally don’t know how to feel about the tractability of anti-aging.

Of course, to the extent that your post is just arguing “governments should fund this area more, it seems obviously under-resourced”, then that’s a pretty low bar, and your graph of the NIH’s painfully skewed funding priorities basically makes the entire argument for you. (Although I note that the graph seems incorrect?? Shouldn’t $500M be much larger than one row of pixels?? Compare to the nearby “$7B” figures; the $500M should of course be 1/14th as tall...) For this purpose, it’s fine IMO to argue “aging is objectively very important, it doesn’t even matter how non-tractable it is, SURELY we ought to be spending more than $500m/year on this, at the very least we should be spending more than we do on Alzheimers which we also don’t understand but is an objectively smaller problem.”

But if you are trying to convince venture-capitalists to invest in anti-aging with the expectation of maybe actually turning a profit, or win over philanthropists who have other pressing funding priorities, then going into more detail on tractability is probably necessary.

The pension crisis in many developed countries stems from a demographic imbalance: people are living longer, but the retirement age and working lifespan have remained relatively fixed. This leads to fewer workers supporting more retirees over time, creating unsustainable economic pressure on pension systems.

Let’s imagine we slow or even reverse aging. This wouldn’t just extend life span it would extend healthspan. In practical terms, more people could remain physically and cognitively healthy well into what is currently considered “old age.”

So curing aging (the ultimate goal of longevity) would solve the pension crisis in the West and the need for mass migration.