Scriptwriter for RationalAnimations! Interested in lots of EA topics, but especially ideas for new institutions like prediction markets, charter cities, georgism, etc. Also a big fan of EA / rationalist fiction!

Jackson Wagner

it also advocates for the government of California to in-house the engineering of its high-speed rail project rather than try to outsource it to private contractors

Hence my initial mention of “high state capacity”? But I think it’s fair to call abundance a deregulatory movement overall, in terms of, like… some abstract notion of what proportion of economic activity would become more vs less heavily involved with government, under an idealized abundance regime.

Sorry to be confusing by “unified”—I didn’t mean to imply that individual people like klein or mamdani were “unified” in toeing an enforced party line!

Rather I was speculating that maybe the reason the “deciding to win” people (moderates such as matt yglesias) and the “abundance” people, tend to overlap moreso than abundance + left-wingers, is because the abundance + moderates tend to share (this is what I meant by “are unified by”) opposition to policies like rent control and other price controls, tend to be less enthusiastic about “cost-disease-socialism” style demand subsidies since they often prefer to emphasize supply-side reforms, tend to want to deemphasize culture-war battles in favor of an emphasis on boosting material progress / prosperity, etc. Obviously this is just a tendency, not universal in all people, as people like mamdani show.

FYI, I’m totally 100% on board with your idea that abundance is fully compatible with many progressive goals and, in fact, is itself a deeply progressive ideology! (cf me being a huge georgist.) But, uh, this is the EA Forum, which is in part about describing the world truthfully, not just spinning PR for movements that I happen to admire. And I think it’s an appropriate summary of a complex movement to say that abundance stuff is mostly a center-left, deregulatory, etc movement.

Imagine someone complaining—it’s so unfair to describe abundance as a “democrat” movement!! That’s so off-putting for conservatives—instead of ostracising them, we should be trying to entice them to adopt these ideas that will be good for the american people! Like Montana and Texas passing great YIMBY laws, Idaho deploying modular nuclear reactors, etc. In lots of ways abundance is totally coherent with conservative goals of efficient government services, human liberty, a focus on economic growth, et cetera!!

That would all be very true. But it would still be fair to summarize abundance as primarily a center-left democrat movement.

To be clear I personally am a huge abundance bro, big-time YIMBY & georgist, fan of the Institute for Progress, personally very frustrated by assorted government inefficiencies like those mentioned, et cetera! I’m not sure exactly what the factional alignments are between abundance in particular (which is more technocratic / deregulatory than necessarily moderate—in theory one could have a “radical” wing of an abundance movement, and I would probably be an eager member of such a wing!) and various forces who want the Dems to moderate on cultural issues in order to win more (like the recent report “Deciding to Win”). But they do strike me as generally aligned (perhaps unified in their opposition to lefty economic proposals which often are neither moderate nor, like… correct).

A couple more “out-there” ideas for ecological interventions:

“recording the DNA of undiscovered rainforest species”—yup, but it probably takes more than just DNA sequences on a USB drive to de-extinct a creature in the future. For instance, probably you need to know about all kinds of epigenetic factors active in the embryo of the creature you’re trying to revive. To preserve this epigenetic info, it might be easiest to simply freeze physical tissue samples (especially gametes and/or embryos) instead of doing DNA sequencing. You might also need to use the womb of a related species—bringing back mammoths is made a LOT easier by the fact that elephants are still around! -- and this would complicate plans to bring back species that are only distantly related to anything living. I want to better map out the tech tree here, and understand what kinds of preparation done today might aid what kinds of de-extinction projects in the future.

Normal environmentalists worry about climate change, habitat destruction, invasive species, pollution, and other prosaic, slow-rolling forms of mild damage to the natural environment. Not on their list: nuclear war, mirror bacteria, or even something as simple as AGI-supercharged economic growth that sees civilization’s economic footprint doubling every few years. I think there is a lot that we could do, relatively cheaply, to preserve at least some species against such catastrophes.

For example, seed banks exist. But you could possibly also save a lot of insects from extinction by maintaining some kind of “mostly-automated insect zoo in a bunker”, a sort of “generation ship” approach as oppoed to the “cryosleep” approach that seedbanks can use. (Also, are even today’s most hardcore seed banks hardened against mirror bacteria and other bio threats? Probably not! Nor do many of them even bother storing non-agricultural seeds for things like random rainforest flowers.)

Right now, land conservation is one of the cheapest ways of preventing species extinctions. But in an AGI-transformed world, even if things go very well for humanity, the economy will be growing very fast, gobbling up a lot of land, and probably putting out a lot of weird new kinds of pollution. (Of course, we could ask the ASI to try and mitigate these environmental impacts, but even in a totally utopian scenario there might be very strong incentives to go fast, eg to more quickly achieve various sublime transhumanist goods and avoid astronomical waste.) By contrast, the world will have a LOT more capital, and the cost of detailed ecological micromanagement (using sensors to gather lots of info, using AI to analyze the data, etc) will be a lot lower. So it might be worth brainstorming ahead of time what kinds of ecological interventions might make sense in such a world, where land is scarce but capital is abundant and customized micro-attention to every detail of an environment is cheap. This might include high-density zoos like described earlier, or “let the species go extinct for now, but then reliably de-extinct them from frozen embryos later”, or “all watched over by machines of loving grace”-style micromanaged forests that achieve superhumanly high levels of biodiversity in a very compact area (and minimizing wild animal suffering by both minimizing the necessary population and also micromanaging the ecology to keep most animals in the population in a high-welfare state).

A lot of today’s environmental-protection / species-extinction-avoidance programs aren’t even robust to, like, a severe recession that causes funding for the program to get cut for a few years! Mainstream environmentalism is truly designed for a very predictable, low-variance future… it is not very robust to genuinely large-scale shocks.

It’s kind of fuzzy and unclear what’s even important about avoiding species extinctions or preserving wild landscapes or etc, since these things don’t fit neatly into a total-hedonic-utilitarian framework. (In this respect, eco-value is similar to a lot of human culture and art, or values like “knowledge” or “excellence” and so forth.) But, regardless of whether or not we can make philosophical progress clarifying exactly what’s important about the natural world, maybe in a utopian future we could find crazy futuristic ways of generating lots more ecological value? (Obviously one would want to do this while avoiding creating lots of wild-animal suffering, but I think this still gives us lots of options.)

Obviously stuff like “bringing back mammoths” is in this category.

But maybe also, like, designing and creating new kinds of life? Either variants of earth life (what kinds of interesting things might dinosaurs have evolved into, if they hadn’t almost all died out 65 million years ago?), or totally new kinds of life that might be able to thrive on, eg, Titan or Europa (though obviously this sort of research might carry some notable bio-risks a la mirror bacteria, thus should perhaps only be pursued from a position of civilizational existential security).

Creating simulated, digital life-forms and ecologies? In the same way that a culture really obsessed with cool crystals, might be overjoyed to learn about mathematics and geometry, which lets them study new kinds of life.

There is probably a lot of exciting stuff you could do with advanced biotech / gene editing technologies, if the science advances and if humanity can overcome the strong taboo in environmentalism against taking active interventions in nature. (Even stuff like “take some seeds of plants threatened by global warming, drive them a few hours north, and plant them there where it’s cooler and they’ll survive better” is considered controversial by this crowd!)

Just like gene drives could help eradicate / suppress human scourges like malaria-carrying mosquitoes, we could also use gene drives to do tailored control of invasive species (which are something like the #2 cause of species extinctions, after #1 habitat destruction). Right now, the best way to control invasive species is often “biocontrol” (introducing natural predators of the species that’s causing problems) -- biocontrol actually works much better than its terrible reputation suggests, but it’s limited by the fact that there aren’t always great natural predators available, it takes a lot of study and care to get it right, etc.

Possibly you could genetically-engineer corals to be tolerant of slightly higher temperatures, and generally use genetic tech to help species adapt more quickly to a fast-changing world.

EcoResilience Inititative is working on applying EA principles (ITN analysis, cost-effectiveness, longtermist orientation, etc) to ecological conservation. But right now it’s just my wife Tandena and a couple of her friends doing research on a part-time volunteer basis, no funding or anything, lol.

Here are two recent posts of theirs describing their enthusiasm for precision fermentation technologies (already a darling of the animal-welfare wing of EA) due to its potentially transformative impact on land use if lots of people ever switch from eating meat towards eating more precision-fermentation protein. And here are some quick takes of theirs on deep ocean mining (investigating the ecological benefits of mining the seabed and thereby alleviating current economic pressures to mine in rainforest areas) and biobanking (as a cheap way of potentially enabling future de-extinction efforts, once de-extinction technology is further advanced).

There are also some bigger, more established EA groups that focus mostly on climate interventions (Giving Green, Founder’s Pledge, etc); most of these have at least done some preliminary explorations into biodiversity, although there is not really much published work yet. Hannah Ritchie at OurWorldInData has compiled some interesting information about various ecological problems, and her book “Not The End of the World” is great—maybe the best starting place for someone who wants to get involved to learn more?

There is a very substantial “abundance” movement that (per folks like matt yglesias and ezra klein) is seeking to create a reformed, more pro-growth, technocratic, high-state-capacity democratic party that’s also more moderate and more capable of winning US elections. Coefficient Giving has a big $120 million fund devoted to various abundance-related causes, including zoning reform for accelerating housing construction, a variety of things related to building more clean energy infrastructure, targeted deregulations aimed at accelerating scientific / biomedical progress, etc. https://coefficientgiving.org/research/announcing-our-new-120m-abundance-and-growth-fund/

You can get more of a sense of what the abundance movement is going for by reading “the argument”, an online magazine recently funded by Coefficient giving and featuring Kelsey Piper, a widely-respected EA-aligned journalist: https://www.theargumentmag.com/

I think EA the social movement (ie, people on the Forum, etc) try to keep EA somewhat non-political to avoid being dragged into the morass of everything becoming heated political discourse all the time. But EA the funding ecosystem is significantly more political, also does a lot of specific lobbying in connection to AI governance, animal welfare, international aid, etc.

Yup, I think there’s a lot of very valuable research / brainstorming / planning that EA (and humanity overall) hasn’t yet done to better map out the space of ways that we could create moral value far greater than anything we’ve seen in history so far.

In EA / rationalist circles, discussion of “flourishing futures” often focuses on “transhumanist goods”, like:

extreme human longevity / immortality through super-advanced medical science

intelligence amplification

reducing suffering, and perhaps creating new kinds of extremely powerful positive emotions

you also hear a bit about AI welfare, and the idea that maybe we could create AI minds experiencing new forms of valuable subjective experience

But there are perhaps a lot of other directions worth exploring:

various sorts of spiritual attainment that might be possible with advanced technology / digital minds / etc

things that are totally out of left field to us because we can’t yet imagine them, like how the value of consciousness would be a bolt from the blue to a planet that only had plants & lower life forms.

instantiating various values, like beauty or cultural sophistication or ecological richness, to extreme degrees

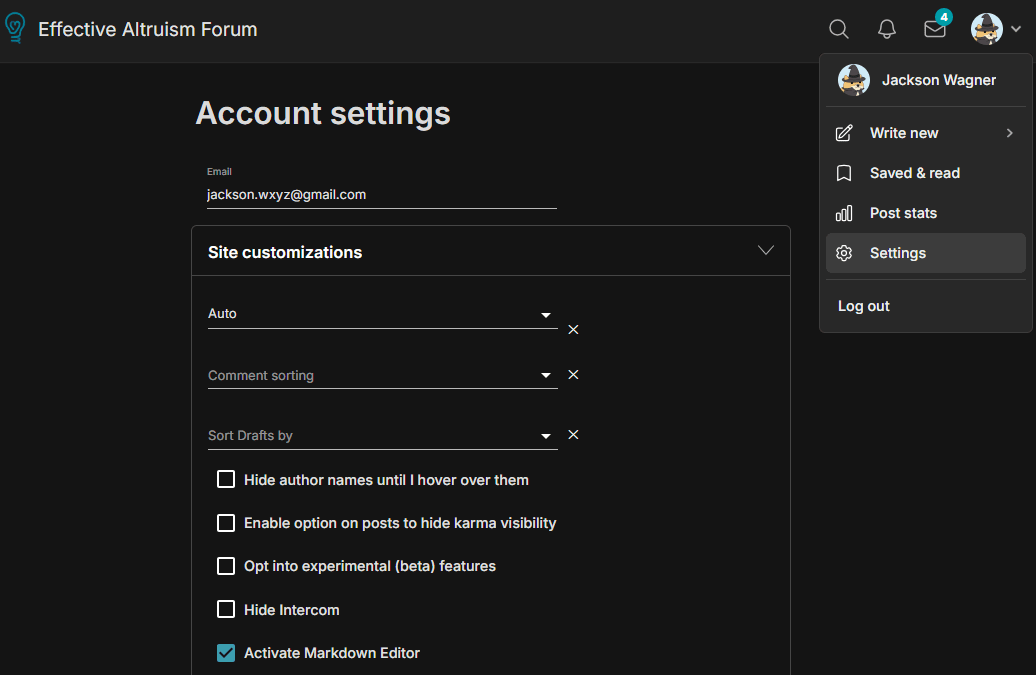

On a more practical note, the Forum does support markdown headings if you enable the “activate markdown editor” feature on the EA Forum profile settings! This would turn all your ##headings into a much more beautiful, readable structure (and it would create a little outline in a sidebar, for people to jump around to different sections).

[content warning: buncha rambly thoughts that might not make much sense]

certainly—see my bit about how my preferred solution would be to run a volunteer army even if that takes ruinously high taxes on the rest of the population. (The United States, to its credit, has indeed run an all-volunteer army ever since the end of the Vietnam War in 1973! But having an immense population makes this relatively easy; smaller countries face sharper trade-offs and tend to orient more towards conscription. See for instance the fact that Russia’s army is less reliant on conscripts than Ukraine’s.)

but also, almost every policy in society has unequal benefits, perhaps helping a small group at the expense of more diffuse harm to a larger group, or vice versa. For example, greater investment in bike lanes and public transit (at the expense of simply building more roads) helps cyclists and public-transit users at the expense of car-drivers. Using taxes to fund a public-school system is basically ripping off people who don’t have children and subsidizing those that do; et cetera. at some point, instead of trying to make sure that every policy comes out even for everyone involved, you have to just kind of throw up your hands, hope that different policies pointing in different directions even out in the end, and rely on some sense of individual willingness to sacrifice for the common good to smooth over the asymmetries.

One could similarly say it’s unfair that residents of Lviv (who are very far from the Ukranian front line, and would almost certainly remain part of a Ukrainian “rump state” even in the case of dramatic eventual Russian victory) are being asked to make large sacrifices for the defense of faraway eastern Ukraine. (And why are residents of southeastern Poland, so near to Lviv, asked to sacrifice so much less than their neighbors?!)

Perhaps there is some galaxy-brained solution to problems like this, where all of Europe (or all of Ukraine’s allies, globally) could optimally tax themselves some fractional percent in accordance with how near or far they are to Ukraine itself? Or one could be even more idealistic and imagine a unified coalition of allies where everyone decides centrally which wars to support and then contributes resources evenly to that end (such that the armies in eastern Ukraine would have a proportionate number of frenchmen, americans, etc). But in practice nobody has figured out how a scheme like that would possibly work, or why countries would be motivated to adopt it, how it could be credibly fair and neutral and immune to various abuses, etc.

Another weakness to the idea of democratic feedback is simply that it isn’t very powerful—every couple of years you get essentially a binary choice between the leading two coalitions, so you can do a reasonably good job expressing your opinion on whatever is considered the #1 issue of the day, but it’s very hard to express nuanced views on multiple issues through the use of just one vote. So, in this sense, democracy isn’t really a guarantee of representation across many issues, so much as a safety valve that will hopefully fix problems one-by-one as they rise to the position of #1 most-egregiously-wrong-thing in society.

I think that today’s “liberal democracy” is pretty far from some kind of ethically ideal world with optimally representative governance (or optimally pursuing-the-welfare-of-the-population governance, which might be a totally different system)! Whatever is the ideal system of optimal governance, it would probably seem pretty alien to us, perhaps extremely convoluted in parts (like the complicated mechanisms for Venice selecting the Doge) and overly-financialized in certain ways (insofar as it might rely on weird market-like mechanisms to process information).

But conscription doesn’t stand out to me as being especially worse than other policy issues that are similarly unfair in this regard (maybe it’s higher-stakes than those other issues, but it’s similar in kind) -- it’s a little unfair and inelegant and kind of a blunt instrument, just like all of our policies are in this busted world where nations are merely operating with “the worst form of government, except for all the others that have been tried”.

People also talked about “astronomical waste” (per the nick bostrom paper) -- the idea that we should race to colonize the galaxy as quickly as possible because we’re losing literally a couple galaxies every second we delay. (But everyone seemed to agree that this wasn’t practical, racing to colonize the galaxy soonest would have all kinds of bad consequences that would cause the whole thing to backfire, etc)

People since long before EA existed have been concerned about environmentalist causes like preventing species extinctions, based on a kind of emotional proto-longtermist feeling that “extinction is forever” and it isn’t right that humanity, for its short-term benefit, should cause irreversible losses to the natural world. (Similar “extinction is forever” thinking applies to the way that genocide—essentially seeking the extinction of a cultural / religious / racial / etc group, is considered a uniquely terrible horror, worse than just killing an equal number of randomly-selected people.)

A lot of “improving institutional decisionmaking” style interventions make more and more sense as timelines get longer (since the improved institutions and better decisions have more time to snowball into better outcomes).

With your FTX thought experiment, the population being defrauded (mostly rich-world investors) is different from the population being helped (people in poor countries), so defrauding the investors might be worthwhile in a utilitarian sense (the poor people are helped more than the investors are harmed), but it certainly isn’t in the investors’ collective interest to be defrauded!! (Unless you think the investors would ultimately profit more by being defrauded and seeing higher third-world economic growth, than by not being defrauded. But this seems very unlikely & also not what you intended.)

I might be in favor of this thought experiment if the group of people being stolen from was much larger—eg, the entire US tax base, having their money taken through taxes and redistributed overseas through USAID to programs like PEPFAR… or ideally the entire rich world including europe, japan, middle-eastern petro-states, etc. The point being that it seems more ethical to me to justify coercion using a more natural grouping like the entire world population, such that the argument goes “it’s in the collective benefit of the average human, for richer people to have some of their money transferred to poorer people”. Verus something about “it’s in the collective benefit of all the world’s poor people plus a couple of FTX investors, to take everything the FTX investors own and distribute it among the poor people” seems like a messier standard that’s much more ripe for abuse (since you could always justify taking away anything from practically anyone, by putting them as the sole relatively-well-off member of a gerrymandered group of mostly extremely needy people).

It also seems important that taxes for international aid are taken in a transparent way (according to preexisting laws, passed by a democratic government, that anyone can read) that people at least have some vague ability to give democratic feedback on (ie by voting), rather than being done randomly by FTX’s CEO without even being announced publicly (that he was taking their money) until it was a fait accompli.

Versus I’m saying that various forms of conscription / nationalization / preventing-people-and-capital-from-fleeing (ideally better forms rather than worse forms) seems morally justified for a relatively-natural group (ie all the people living in a country that is being invaded) to enforce, when it is in the selfish collective interest of the people in that group.

huw said “Conscription in particular seems really bad… if it’s a defensive war then defending your country should be self-evidently valuable to enough people that you wouldn’t need it.”

I’m saying that huw is underrating the coordination problem / bank-run effect. Rather than just let individuals freely choose whether to support the war effort (which might lead the country to quickly collapse even if most people would prefer that the country stand and fight), I think that in an ideal situation:

1. people should have freedom of speech to argue for and against different courses of action—some people saying we should surrender because the costs of fighting would be too high and occupation won’t be so bad, others arguing the opposite. (This often doesn’t happen in practice—places like Ukraine will ban russia-friendly media, governments like the USA in WW2 will run pro-war support-the-trooops propaganda and ban opposing messages, etc. I think this is where a lot of the badness of even defensive war comes from—people are too quick to assume that invaders will be infinitely terrible, that surrender is unthinkable, etc.)

2. then people should basically get to occasionally vote on whether to keep fighting the war or not, what liberties to infringe upon versus not, etc (you don’t necessarily need to vote right at the start of the war, since in democracy there’s a preexisting social contract including stuff like “if there’s a war, some of you guys are getting drafted, here’s how it works, by living here as a citizen you accept these terms and conditions”)

IMO, under those conditions (and as long as the burdens / infringements-of-liberty of the war are reasonably equitably shared throughout society, not like people voting “let’s send all the ethnic-minority people to fight while we stay home”), it is ethically justifiable to do quite a lot of temporarily curtailing individual liberties in the name of collective defense.Back to finance analogy: sometimes non-fraudulent banks and investment funds do temporarily restrict withdrawals, to prevent bank-runs during a crisis. Similarly, stock exchanges implement “circuit-breakers” that suspend trading, effectively freezing everyone’s money and preventing them from selling their stock, when markets crash very quickly. These methods are certainly coercive, and they don’t always even work well in practice, but I think the reason they’re used is because many people recognize that they do a better-than-the-alternative job of looking out for investors’ collective interests.

This isn’t part of your thought experiment, but in the real world, even if FTX had spent a much higher % of their ill-gotten treasure on altruistic endeavors, the whole thing probably backfired in the end due to reputational damage (ie, the reputational damage to the growth of the EA movement hurt the world much more than the FTX money donated in 2020 − 2022 helped).

And in general this is true of unethical / illegal / coercive actions—it might seem like a great idea to earn some extra cash on the side is beating up kids for their lunch money, but actually the direct effect of stealing the money will be overriden by the second-order effect of your getting arrested, fined, thrown in jail, etc.

But my impression is that most defensive wars don’t backfire in this way?? Ukraine or Taiwan might be making an ethical or political mistake if they decide to put up more of a fight by fighting back against an invader, but it’s not like conscripting more people to send to the front is going to paradoxically result in LESS of a fight being put up! Nations siezing resources & conscripting people in order to fight harder, generally DOES translate straightforwardly into fighting harder. (Except on the very rare occasion when people get sufficiently fed up that they revolt in favor of a more surrender-minded government, like Russia in 1918 or Paris in 1871.)

To be clear, I am not saying that conscription is always justified or that “it’s solving a coordination problem” is a knockdown argument in all cases. (If I believed this, then I would probably be in favor of some kind of extreme communist-style expropriation and redistribution of economic resources, like declaring that the entire nation is switching to 100% Georgist land value taxes right now, with no phase-in period and no compensating people for their fallen property values. IRL I think this would be wrong, even though I’m a huge fan of more moderate forms of Georgism.) But I think it’s an important argument that might tip the balance in many cases.

Finally, to be clear, I totally agree with you that conscription is a very intense infringement on individual human liberty! I’m just saying that sometimes, if a society is stuck between a rock and a hard place, infringements on liberty can be ethically justifiable IMO. (Ideally IMO I’d like it if countries, even under dire circumstances, should try to pay their soldiers at least something reasonably close to the “free-market wage”, ie the salary that would get them to willingly volunteer. If this requires extremely high taxes on the rest of the populace, so be it! If the citizens hate taxes so much, then they can go fight in the war and get paid instead of paying the taxes! And thereby a fair equilibrium can be determined, whereby the burden of warfighting is being shared equally between citizens & soldiers. But my guess is that most ordinary people in a real-world scenario would probably vote for traditional conscription, rather than embracing my libertarian burden-sharing scheme, and I think their democratic choice is also worthy of respect even if it’s not morally optimal in my view.)

Also agreed that societies in general seem a little too rearing-to-go to get into fights, likely make irrational decisions on this basis, etc. It would be great if everyone in the world could chill out on their hawkishness by like 50% or more… unfortunately there are probably weird adversarial dynamics where you have to act freakishly tough & hawkish in order to create credible deterrence, so it’s not obvious that individual countries should “unilaterally disarm” by doving-out (although over the long arc of history, democracies have generally sort of done this, seemingly to their great benefit). But to the extent anybody can come up with some way to make the whole world marginally less belligerent, that would obviously be a huge win IMO.

But there’s clearly a coordination problem around defense that conscription is a (brute) solution to.

Suppose my country is attacked by a tyrranical warmonger, and to hold off the invaders we need 10% the population to go fight (and some of them will die!) in miserable trench warfare conditions. The rest need to work on the homefront, keeping the economy running, making munitions etc. Personally I’d rather work on the homefront (or just flee the country, perhaps)! But if everyone does that, nobody will head to the trenches, the country will quickly fold, and the warmonger invader will just roll right on to the next country (which will similarly fold)!

It seems almost like a “run on the bank” dynamic—it might be in everyone’s collective interests to put up a fight, but it’s in everyone’s individual interests to simply flee. So, absent some more elegant galaxy-brained solution (assurance contracts, prediction markets, etc??) maybe the government should defend the collective interests of society by stepping in to prevent people from “running on the bank” by fleeing the country / dodging the draft.

(If the country being invaded is democratic and holds elections during wartime, this decision would even have collective approval from citizens, since they’d regularly vote on whether to continue their defensive war or change to a government more willing to surrender to the invaders.)

Of course there are better and worse forms of conscription: paying soldiers enough that you don’t need conscription is better than paying them only a little (although in practice high pay might strain the finances of an invaded country), which is better than not paying them at all.

The OP seems to be viewing things entirely from the perspective of individual rights and liberties, but not proposing how else we might solve the coordination problem of providing for collective defense.

Eg, by his own logic, OP should surely agree that taxes are theft, any governments funded by such flagrant immoral confiscation are completely illegitimate, and anarcho-capitalism is the only ethically acceptable form of human social relations. Yet I suspect the OP does not believe this, even though the analogy to conscription seems reasonably strong (albeit not exact).

Wow, sounds like a really fun format to have different philosophers all come and pitch their philosophy as the best approach to life! I’d love to take a class like that.

Reposting here a recent comment of mine listing socialist-adjacent ideas that at least I personally am a lot more excited about than socialism itself.

* * *FYI, if you have not yet heard of “Georgism” (see this series of blog posts on Astral Codex Ten), you might be in for a really fun time! It’s a fascinating idea that aims to reform capitalism by reducing the amount of rent-seeking in the economy, thus making society fairer and more meritocratic (because we are doing a better job of rewarding real work, not just rewarding people who happen to be squatting on valuable assets) while also boosting economic dynamism (by directing investment towards building things and putting land to its most productive use, rather than just bidding up the price of land).

A few other weird optimal-governance schemes that have socialist-like egalitarian aims but are actually (or at least partially) validated by our modern understanding of economics:using prediction markets to inform institutional decision-making (see this entertaining video explainer), and the wider field of wondering if there are any good ways to improve institutions’ decisions

using quadratic funding to optimally* fund public goods without relying on governments or central planning. (*in theory, given certain assumptions, real life is more complicated, etc etc)

pigouvian taxes (like taxes on cigarrettes or carbon emissions). Like georgist land-value taxes, these attempt to raise funds (for providing public goods either through government services or perhaps quadratic funding) in a way that actually helps the economy (by properly pricing negative externalities) rather than disincentivizing work or investment.

various methods of trying to improve democratic mechanisms to allow people to give more useful, considered input to government processes—approval voting, sortition / citizen’s assemblies, etc

conversation-mapping / consensus-building algorithms like pol.is & community notes

not exactly optimal governance, but this animated video explainer lays out GiveDirectly’s RCT-backed vision of how it’s actually pretty plausible that we could solve extreme poverty by just sending a ton of money to the poorest countries for a few years, which would probably actually work because 1. it turns out that most poor countries have a ton of “slack” in their economy (as if they’re in an economic depression all the time), so flooding them with stimulus-style cash mostly boosts employment and activity rather than just causing inflation, and 2. after just a few years, you’ll get enough “capital accumulation” (farmers buying tractors, etc) that we can taper off the payments and the countries won’t fall back into extreme poverty + economic depression

the dream (perhaps best articulated by Dario Amodei in sections 2, 3, and 4 of his essay “machines of loving grace”, but also frequently touched on by Carl Schulman) of future AI assistants that improve the world by actually making people saner and wiser, thereby making societies better able to coordinate and make win-win deals between different groups.

the concern (articulated in its negative form at https://gradual-disempowerment.ai/, and in its positive form at Sam Altman’s essay Moore’s Law for Everything), that some socialist-style ideas (like redistributing control of capital and providing UBI) might have to come back in style in a big way, if AI radically alters humanity’s economic situation such that the process of normal capitalism starts becoming increasingly unaligned from human flourishing.

Reposting here a recent comment of mine listing socialist-adjacent ideas that at least I personally am a lot more excited about than socialism itself.

* * *FYI, if you have not yet heard of “Georgism” (see this series of blog posts on Astral Codex Ten), you might be in for a really fun time! It’s a fascinating idea that aims to reform capitalism by reducing the amount of rent-seeking in the economy, thus making society fairer and more meritocratic (because we are doing a better job of rewarding real work, not just rewarding people who happen to be squatting on valuable assets) while also boosting economic dynamism (by directing investment towards building things and putting land to its most productive use, rather than just bidding up the price of land). Check it out; it might scratch an itch for “something like socialism, but that might actually work”.

A few other weird optimal-governance schemes that have socialist-like egalitarian aims but are actually (or at least partially) validated by our modern understanding of economics:using prediction markets to inform institutional decision-making (see this entertaining video explainer), and the wider field of wondering if there are any good ways to improve institutions’ decisions

using quadratic funding to optimally* fund public goods without relying on governments or central planning. (*in theory, given certain assumptions, real life is more complicated, etc etc)

pigouvian taxes (like taxes on cigarrettes or carbon emissions). Like georgist land-value taxes, these attempt to raise funds (for providing public goods either through government services or perhaps quadratic funding) in a way that actually helps the economy (by properly pricing negative externalities) rather than disincentivizing work or investment.

various methods of trying to improve democratic mechanisms to allow people to give more useful, considered input to government processes—approval voting, sortition / citizen’s assemblies, etc

conversation-mapping / consensus-building algorithms like pol.is & community notes

not exactly optimal governance, but this animated video explainer lays out GiveDirectly’s RCT-backed vision of how it’s actually pretty plausible that we could solve extreme poverty by just sending a ton of money to the poorest countries for a few years, which would probably actually work because 1. it turns out that most poor countries have a ton of “slack” in their economy (as if they’re in an economic depression all the time), so flooding them with stimulus-style cash mostly boosts employment and activity rather than just causing inflation, and 2. after just a few years, you’ll get enough “capital accumulation” (farmers buying tractors, etc) that we can taper off the payments and the countries won’t fall back into extreme poverty + economic depression

the dream (perhaps best articulated by Dario Amodei in sections 2, 3, and 4 of his essay “machines of loving grace”, but also frequently touched on by Carl Schulman) of future AI assistants that improve the world by actually making people saner and wiser, thereby making societies better able to coordinate and make win-win deals between different groups.

the concern (articulated in its negative form at https://gradual-disempowerment.ai/, and in its positive form at Sam Altman’s essay Moore’s Law for Everything), that some socialist-style ideas (like redistributing control of capital and providing UBI) might have to come back in style in a big way, if AI radically alters humanity’s economic situation such that the process of normal capitalism starts becoming increasingly unaligned from human flourishing.

Reposting a comment of mine from another user’s similar post about “I used to be socialist, but now have seen the light”!

* * *FYI, if you have not yet heard of “Georgism” (see this series of blog posts on Astral Codex Ten), you might be in for a really fun time! It’s a fascinating idea that aims to reform capitalism by reducing the amount of rent-seeking in the economy, thus making society fairer and more meritocratic (because we are doing a better job of rewarding real work, not just rewarding people who happen to be squatting on valuable assets) while also boosting economic dynamism (by directing investment towards building things and putting land to its most productive use, rather than just bidding up the price of land). Check it out; it might scratch an itch for “something like socialism, but that might actually work”.

A few other weird optimal-governance schemes that have socialist-like egalitarian aims but are actually (or at least partially) validated by our modern understanding of economics:using prediction markets to inform institutional decision-making (see this entertaining video explainer), and the wider field of wondering if there are any good ways to improve institutions’ decisions

using quadratic funding to optimally* fund public goods without relying on governments or central planning. (*in theory, given certain assumptions, real life is more complicated, etc etc)

pigouvian taxes (like taxes on cigarrettes or carbon emissions). Like georgist land-value taxes, these attempt to raise funds (for providing public goods either through government services or perhaps quadratic funding) in a way that actually helps the economy (by properly pricing negative externalities) rather than disincentivizing work or investment.

various methods of trying to improve democratic mechanisms to allow people to give more useful, considered input to government processes—approval voting, sortition / citizen’s assemblies, etc

conversation-mapping / consensus-building algorithms like pol.is & community notes

not exactly optimal governance, but this animated video explainer lays out GiveDirectly’s RCT-backed vision of how it’s actually pretty plausible that we could solve extreme poverty by just sending a ton of money to the poorest countries for a few years, which would probably actually work because 1. it turns out that most poor countries have a ton of “slack” in their economy (as if they’re in an economic depression all the time), so flooding them with stimulus-style cash mostly boosts employment and activity rather than just causing inflation, and 2. after just a few years, you’ll get enough “capital accumulation” (farmers buying tractors, etc) that we can taper off the payments and the countries won’t fall back into extreme poverty + economic depression

the dream (perhaps best articulated by Dario Amodei in sections 2, 3, and 4 of his essay “machines of loving grace”, but also frequently touched on by Carl Schulman) of future AI assistants that improve the world by actually making people saner and wiser, thereby making societies better able to coordinate and make win-win deals between different groups.

the concern (articulated in its negative form at https://gradual-disempowerment.ai/, and in its positive form at Sam Altman’s essay Moore’s Law for Everything), that some socialist-style ideas (like redistributing control of capital and providing UBI) might have to come back in style in a big way, if AI radically alters humanity’s economic situation such that the process of normal capitalism starts becoming increasingly unaligned from human flourishing.

Left-libertarian EA here—I’ll always upvote posts along the lines of “I used to be socialist, but now have seen the light”!

FYI, if you have not yet heard of “Georgism” (see this series of blog posts on Astral Codex Ten), you might be in for a really fun time! It’s a fascinating idea that aims to reform capitalism by reducing the amount of rent-seeking in the economy, thus making society fairer and more meritocratic (because we are doing a better job of rewarding real work, not just rewarding people who happen to be squatting on valuable assets) while also boosting economic dynamism (by directing investment towards building things and putting land to its most productive use, rather than just bidding up the price of land). Check it out; it might scratch an itch for “something like socialism, but that might actually work”.

A few other weird optimal-governance schemes that have socialist-like egalitarian aims but are actually (or at least partially) validated by our modern understanding of economics:using prediction markets to inform institutional decision-making (see this entertaining video explainer), and the wider field of wondering if there are any good ways to improve institutions’ decisions

using quadratic funding to optimally* fund public goods without relying on governments or central planning. (*in theory, given certain assumptions, real life is more complicated, etc etc)

pigouvian taxes (like taxes on cigarrettes or carbon emissions). Like georgist land-value taxes, these attempt to raise funds (for providing public goods either through government services or perhaps quadratic funding) in a way that actually helps the economy (by properly pricing negative externalities) rather than disincentivizing work or investment.

various methods of trying to improve democratic mechanisms to allow people to give more useful, considered input to government processes—approval voting, sortition / citizen’s assemblies, etc

conversation-mapping / consensus-building algorithms like pol.is & community notes

not exactly optimal governance, but this animated video explainer lays out GiveDirectly’s RCT-backed vision of how it’s actually pretty plausible that we could solve extreme poverty by just sending a ton of money to the poorest countries for a few years, which would probably actually work because 1. it turns out that most poor countries have a ton of “slack” in their economy (as if they’re in an economic depression all the time), so flooding them with stimulus-style cash mostly boosts employment and activity rather than just causing inflation, and 2. after just a few years, you’ll get enough “capital accumulation” (farmers buying tractors, etc) that we can taper off the payments and the countries won’t fall back into extreme poverty + economic depression

the dream (perhaps best articulated by Dario Amodei in sections 2, 3, and 4 of his essay “machines of loving grace”, but also frequently touched on by Carl Schulman) of future AI assistants that improve the world by actually making people saner and wiser, thereby making societies better able to coordinate and make win-win deals between different groups.

the concern (articulated in its negative form at https://gradual-disempowerment.ai/, and in its positive form at Sam Altman’s essay Moore’s Law for Everything), that some socialist-style ideas (like redistributing control of capital and providing UBI) might have to come back in style in a big way, if AI radically alters humanity’s economic situation such that the process of normal capitalism starts becoming increasingly unaligned from human flourishing.

Agreed that it’s a weird mood, but perhaps inevitable.

In terms of the inequality between running PR campaigns but “not interesting cooprating with other people’s altruistic PR campaigns”: insofar as attention is ultimately a fixed resource, it’s an intrinsically adversarial situation between different attempts to capture peoples’ attention. (Although there are senses in which this is not true—many causes are often bundled together in a political alliance. And there could even be a broader cultural shift towards people caring more about behaving ethically, which would perhaps “lift all boats” in the do-gooder PR-campaign space!) Nevertheless, given the mostly fixed supply of attention, it certainly seems fine to steal eyeballs for thoughtful, highly-effective causes that would otherwise be watching Tiktok, and it seems similarly fine to steal eyeballs for good causes that would otherwise have gone to dumb, counterproductive causes (like the great paper-straw crusade). After that, it seems increasingly lamentable to steal eyeballs from increasingly reasonably-worthy causes, until you get to the level of counterproductive infighting among people who are all trying hard to make the world a better place. Of course, this is complicated by the fact that everyone naturally thinks their own cause is worthier than others. Nevertheless, I think some causes are worthier than others, and fighting to direct attention towards the worthiest causes is a virtuous thing to do—perhaps even doing one’s civic duty as a participant in the “marketplace of ideas”.

In terms of the inequality between organizers (who are being high-impact only because others are low impact) vs consumers whose behavior is affected:This is omnipresent everywhere in EA, right? Mitigating x-risks is only high-impact because the rest of the world is neglecting it so badly!

Are we cruelly “stealing their impact”? I mean, maybe?? But this doesn’t seem so bad, because other people don’t care as much about impact. Conversely, some causes are much better than EA at going viral and raising lots of shallow mass awareness—but this isn’t so terrible from EA’s perspective, because EA doesn’t care as much about going viral.

But talk of “stealing impact” is weird and inverted… Imagine if everyone turned EA and tried to do the most high-impact thing. In this world, it might harder to have very high impact, but this would hardly be cause for despair, because the actual world would be immensely better off! It seems perverse to care about imagined “impact-stealing” rather than the actual state of the world.

It also seems like a fair deal insofar as the organizers have thought carefully and worked hard (a big effort), while it’s not like the consumers are being coerced into doing menial low-impact gruntwork for long hours and low pay; they’re instead making a tiny, nearly unconscious choice between two very similar options. In a way, the consumers are doing marginal charity, so their impact is higher than it seems. But asking people to go beyond marginal charity and make costlier sacrifices (ie, join a formal boycott, or consciously keep track of long lists of which companies are good versus bad) seems like more of an imposition.

Re: Nestle in particular, I get the spirit of what you’re saying, although see my recent long comment where I try to think through the chocolate issue in more detail. As far as I can tell, the labor-exploitation problems are common to the entire industry, so switching from Nestle to another brand wouldn’t do anything to help?? (If anything, possibly you should be switching TOWARDS nestle, and away from companies like Hershey’s that get a much higher % of their total revenue from chocolate?)

I think this spot-check about Nestle vs cocoa child labor (and about Nestle vs drought, and so forth) illustrates my point that there are a lot of seemingly-altruistic PR campaigns that actually don’t do much good. Perhaps those PR campaigns should feel bad for recruiting so much attention only to waste it on a poorly-thought-out theory of impact!

Hi; thanks for this thoughtful reply!

I agree that with chocolate and exploited labor, the situation is similar to veganism insofar as if you buy some chocolate, then (via the mechanisms of supply and demand) that means more chocolate is gonna be harvested (although not necessarily by harvested by that particular company, right? so I think the argument works best only if the entire field of chocolate production is shot through with exploited labor?). Although, as Toby Chrisford points out in his comment, not all boycott campaigns are like this.Thoughts on chocolate in particular

Reading the wikipedia page for chocolate & child labor, I agree that this seems like a more legit cause than “water privatization” or some of the other things I picked on. But if you are aiming for a veganism-style impact through supply and demand, it makes more sense to boycott chocolate in general, not a specific company that happens to make chocolate. (Perplexity says that Nestle controls only a single-digit percentage of the world’s chocolate market, “while the vast majority is produced by other companies such as Mars, Mondelez, Ferrero, and Hershey”—nor is Nestle even properly described as a chocolate company, since only about 15% of their revenue comes from chocolate! More comes from coffee, other beverages, and random other foods.)

In general I just get the feeling that you are choosing what to focus on based on which companies have encountered “major controversies” (ie charismatic news stories), rather than making an attempt to be scope-sensitive or thinks strategically.

“With something like slave labor in the chocolate supply chain, the impact of an individual purchase is very hard to quantify.”

Challenge accepted!!! Here are some random fermi calculations that I did to help me get a sense of scale on various things:

Google says that the average american consumes 100 lbs of chicken a year, and broiler chickens produce about 4 lbs of meat, so that’s 25 broiler chickens per year. Broiler chickens only live for around 8 weeks, so 25 chickens = at any given time, about four broiler chickens are living in misery in a factory farm, per year, per american. Toss in 1 egg-laying hen to produce about 1 egg per day, that’s five chickens per american.

How bad is chicken suffering? Idk, not that bad IMO, chickens are pretty simple. But I’m not a consciousness scientist (and sadly, nor is anybody else), so who knows!

Meanwhile with chocolate, the average american apparently consumes about 15 pounds of chocolate per year. (Wow, that’s a lot, but apparently europeans eat even more??) The total worldwide market for chocolate is 16 billion pounds per year. Wikipedia says that around 2 million children are involved in child-labor for harvesting cocoa in West Africa, while Perplexity (citing this article) estimates that “Including farmers’ families, workers in transport, trading, processing, manufacturing, marketing, and retail, roughly 40–50 million people worldwide are estimated to depend on the cocoa and chocolate supply chain for their income or employment.”

So the average American’s share of global consumption (15 / 16 billion, or about 1 billionth) is supporting the child labor of 2 million / 1 billion = 0.002 West African children. Or, another way of thinking about this is that (assuming child laborers work 12-hour days every day of the year, which is probably wrong but idk), the average American’s yearly chocolate consumption supports about 9 hours of child labor, plus about 180 hours of labor from all the adults involved in “transport, trading processing, manufacturing, marketing, and retail”, who are hopefully mostly all legitly-employed.

Sometimes for a snack, I make myself a little bowl of mixed nuts + dark chocolate chips + blueberries. I buy these little 0.6-pound bags of dark chocolate chips for $4.29 at the grocery store (which is about as cheap as it’s possible to buy chocolate); each one will typically last me a couple months. It’s REALLY dark chocolate, 72% cacao, so maybe in terms of child-labor-intensity, that’s equivalent to 4x as much normal milk chocolate, so child-labor-equivalent to like 2.5 lbs of milk chocolate? So each of these bags of dark chocolate involves about 1.5 hours of child labor.

The bags cost $4.29, but there is significant consumer surplus involved (otherwise I wouldn’t buy them!) Indeed, I’d probably buy them even if they cost twice as much! So let’s say that the cost of my significantly ycutting back my chocolate consumption is about $9 per bag.

So if I wanted to reduce child labor, I can buy 1 hour of a child’s freedom at a rate of about $9 per bag / 1.5 hours per bag = $6 per hour. (Obviously I can only buy a couple hours this way, because then my chocolate consumption would hit zero and I can’t reduce any more.)

That’s kind of expensive, actually! I only value my own time at around $20 - $30 per hour!

And it looks doubly expensive when you consider that givewell top charities can save an african child’s LIFE for about $5000 in donations—assuming 50 years life expectancy and 16 hours awake a day, that’s almost 300,000 hours of being alive versus dead. Meanwhile, if me and a bunch of my friends all decided to take the hit to our lifestyle in the form of foregone chocolate consumption instead of antimalarial bednet donations, that would only free up something like 833 hours of an african child doing leisure versus labor (which IMO seems less dramatic than being alive versus dead).

One could imagine taking a somewhat absurd “offsetting” approach, by continuing to enjoy my chocolate but donating 3 cents to Against Malaria Foundation for each bag of chocolate I buy—therefore creating 1.8 hours of untimely death --> life in expectation, for every 1.5 hours of child labor I incur.

Sorry to be “that guy”, but is child labor even bad in this context? Is it bad enough to offset the fact that trading with poor nations is generally good?

Obviously it’s bad for children (or for that matter, anyone), who ought to be enjoying their lives and working to fulfill their human potential, to be stuck doing tedious, dangerous work. But, it’s also bad to be poor!

Most child labor doesn’t seem to be slavery—the same wikipedia page that cites 2 million child laborers says there are estimated to be only 15,000 child slaves. (And that number includes not just cocoa, but also cotton and coffee.) So, most of it is more normal, compensated labor. (Albeit incredibly poorly compensated by rich-world standards—but that’s everything in rural west africa!)

By analogy with classic arguments like “sweatshops are good actually, because they are an important first step on the ladder of economic development, and they are often a better option for poor people than their realistic alternatives, like low-productivity agricultural work”, or the infamous Larry Summers controversy (no, not that one, the other one. no, the OTHER other one. no, not that one either...) about an IMF memo speculating about how it would be a win-win situation for developed countries to “export more pollution” to poorer nations, doing the economic transaction whereby I buy chocolate and it supports economic activity in west africa (an industry employing 40 million people, only 2 million of whom are child laborers) seems like it might be better than not doing it. So, the case for a personal boycott of chocolate seems weaker than a personal boycott of factory-farmed meat (where many of the workers are in the USA, which has much higher wages and much tighter / hotter labor markets).

“I am genuinely curious about what you consider to fall within the realm of morally permissible personal actions.”

This probably won’t be a very helpful response, but for what it’s worth:

I don’t think the language of moral obligations and permissibility and rules (what people call “deontology”) is a very good way to think about these issues of diffuse, collective, indirect harms like factory farming or labor exploitation.

As you are experiencing, deontology doesn’t offer much guidance on where to draw the line when it comes to increasingly minor, indirect, or incidental harms.

It’s also not clear what to do when there are conflicting effects at play—if an action is good for some reasons but also bad for other reasons.

Deontology doesn’t feel very scope-sensitive—it just says something like “don’t eat chocolate if child labor is involved!!” and nevermind if the industry is 100% child labor or 0.01% child labor. This kind of thinking seems to have a tendency to do the “copenhagen theory of ethics” thing where you just pile on more and more rules in an attempt to avoid being entangled with bad things, when instead it should be more concerned with identifying the most important bad things and figuring out how to spend extra energy addressing those, even while letting some more minor goals slide.

I think utilitarianism / consequentialism is a better way to think about diffuse, indirect harms, because it’s more scope-sensitive and it seems to allow for more grey areas and nuance. (Deontology just says that you must do some things and mustn’t do other forbidden things, and is neutral on everything else. But consequentialism rates actions on a spectrum from super-great to super-evil, with lots of medium shades in-between.) It’s also better at balancing conflicting effects—just add them all up!

Of course, trying to live ordinary daily life according to 100% utilitarian thinking and ethics feels just as crazy as trying to live life according to 100% deontological thinking. Virtue ethics often seems like a better guide to the majority of normal daily-life decisionmaking: try to behave honorably, try to be be caring and prudent and et cetera, doing your best to cultivate and apply whatever virtues seem most relevant to the situation at hand.

Personally, although I philosophically identify as a pretty consequentialist EA, in real life I (and, I think, many people) rely on kind of a mushy combination of ethical frameworks, trying to apply each framework to the area where it’s strongest.

As I see it, that’s virtue ethics for most of ordinary life—my social interactions, how I try to motivate myself to work and stay healthy, what kind of person I aim to be.

And I try to use consequentialist / utilitarian thinking to figure out “what are some of the MOST impactful things I could be doing, to do the MOST good in the world”. I don’t devote 100% of my efforts to doing this stuff (I am pretty selfish and lazy, like to have plenty of time to play videogames, etc), but I figure if I spend even a smallish fraction of my time (like 20%) aimed at doing whatever I think is the most morally-good thing I could possibly do, then I will accomplish a lot of good while sacrificing only a little. (In practice, the main way this has played out in my actual life is that I left my career in aerospace engineering in favor of nowadays doing a bunch of part-time contracting to help various EA organizations with writing projects, recruiting, and other random stuff. I work a lot less hard in EA than I did as an aerospace engineer—like I said, I’m pretty lazy, plus I now have a toddler to take care of.)

I view deontological thinking as most powerful as a coordination mechanism for society to enforce standards of moral behavior. So instead of constantly dreaming up new personal moral rules for myself (although like everybody I have a few idiosyncratic personal rules that I try to stick to), I try to uphold the standards of moral behavior that are broadly shared by my society. This means stuff like not breaking the law (except for weird situations where the law is clearly unjust), but also more unspoken-moral-obligation stuff like supporting family members, plus a bunch of kantian-logic stuff like respecting norms, not littering, etc (ie, if it would be bad if everyone did X, then I shouldn’t do X).

But when it comes to pushing for new moral norms (like many of the proposed boycott ideas) rather than respecting existing moral norms, I’m less enthusiastic. I do often try to be helpful towards these efforts on the margin, since “marginal charity” is cheap. (At least I do this when the new norm seems actually-good, and isn’t crazy virtue-signaling spirals like for example the paper-straws thing, or counterproductive in other ways like just sapping attention from more important endeavors or distracting from the real cause of a problem.) But it usually doesn’t seem “morally obligatory” (ie, in my view of how to use deontology, “very important for preserving the moral fabric of society and societal trust”) to go to great lengths to push super-hard for the proposed new norms. Nor does it usually seem like the most important thing I could be doing. So beyond a token, marginal level of support for new norms that seem nice, I usually choose to focus my “deliberately trying to be a good person” effort on trying to do whatever is the most important thing I could be doing!

Thoughts on Longtermism

I think your final paragraph is mixing up two things that are actually separate:

1. “I’m not denying [that x-risks are important] but these seem like issues far beyond the influence of any individual person. They are mainly the domain of governments, policymakers… [not] individual actions.”

2. “By contrast, donating to save kids from malaria or starvation has clear, measurable, immediate effects on saving lives.”

I agree with your second point that sadly, longtermism lacks clear, measurable, immediate effects. Even if you worked very hard and got very lucky and accomplished something that /seems/ like it should be obviously great from a longtermist perspective (like, say, establishing stronger “red phone”-style nuclear hotline links between the US and Chinese governments), there’s still a lot of uncertainty about whether this thing you did (which maybe is great “in expectation”) will actually end up being useful (maybe the US and China never get close to fighting a nuclear war, nobody ever uses the hotline, so all the effort was for naught)! Even in situations where we can say in retrospect that various actions were clearly very helpful, it’s hard to say exactly HOW helpful. Everything feels much more mushy and inexact.

Longtermists do have some attempted comebacks to this philosophical objection, mostly along the lines of “well, your near-term charity, and indeed all your actions, also affect the far future in unpredictable ways, and the far future seems really important, so you can’t really escape thinking about it”. But also, on a much more practical level, I’m very sympathetic to your concern that it’s much harder to figure out where to actually donate money to make AI safety go well than to improve the lives of people living in poor countries or help animals or whatever else—the hoped-for paths to impact in AI are so much more abstract and complicated, one would have to do a lot more work to understand them well, and even after doing all that work you might STILL not feel very confident that you’ve made a good decision. This very situation is probably the reason why I myself (even though I know a ton about some of these areas!!) haven’t made more donations to longtermist cause areas.

But I disagree with your first point, that it’s beyond the power of individuals to influence x-risks or do other things to make the long-term future go well, rather it’s up to governments. And I’m not just talking about individual crazy stories like that one time when Stanislav Petrov might possibly have saved the world from nuclear war. I think ordinary people can contribute in a variety of reasonably accessible ways:

I think it’s useful just to talk more widely about some of the neglected, weird areas that EA works on—stuff like the risk of power concentration from AI, the idea of “gradual disempowerment” over time, topics like wild animal suffering, the potential for stuff like prediction markets and reforms like approval voting to improve the decisionmaking of our political institutions, et cetera. I personally think this stuff is interesting and cool, but I also think it’s societally beneficial to spread the word about it. Bentham’s Bulldog is, I think, an inspiring recent example of somebody just posting on the internet as a path to having a big impact, by effectively raising awareness of a ton of weird EA ideas.

If you’re just like “man, this x-risk stuff is so fricking confusing and disorienting, but it does seem like in general the EA community has been making an outsized positive contribution to the world’s preparedness for x-risks”, then there are ways to support the EA community broadly (or other similar groups that you think are doing good) -- either through donations, or potentially through, like, hosting a local EA meetups, or (as I do) trying to make a career out of helping random EA orgs with work they need to get done.

Some potential EA cause areas are niche enough that it’s possible to contribute real intellectual progress by, again, just kinda learning more about a topic where you maybe bring some special expertise or unique perspective to an area, and posting your own thoughts / research on a topic. Your own post (even though I disagree with it) is a good example of this, as are so many of the posts on the Forum! Another example that I know well is the “EcoResilience Initiative”, a little volunteer part-time research project / hobby run by my wife @Tandena Wagner—she’s just out there trying to figure out what it means to apply EA-style principles (like prioritizing causes by importance, neglectedness, and tractability) to traditional environmental-conservation goals like avoiding species extinctions. Almost nobody else is doing this, so she has been able to produce some unique, reasonably interesting analysis just by sort of… sitting down and trying to think things through!

Now, you might reasonably object: “Sure, those things sound like they could be helpful as opposed to harmful, but what happened to the focus on helping the MOST you possibly can! If you are so eager to criticize the idea of giving up chocolate in favor of the hugely more-effective tactic of just donating some money to givewell top charities, then why don’t you also give up this speculative longtermist blogging and instead try to earn more money to donate to GiveWell?!” This is totally fair and sympathetic. In response I would say:

Personally I am indeed convinced by the (admittedly weird and somewhat “fanatical”) argument that humanity’s long-term future is potentially very, very important, so even a small uncertain effect on high-leverage longtermist topics might be worth a lot more than it seems.

I also have some personal confidence that some of the random, very-indirect-path-to-impact stuff that I get up to, is indeed having some positive effects on people and isn’t just disappearing into the void. But it’s hard to communicate what gives me that confidence, because the positive effects are kind of illegible and diffuse rather than easily objectively measurable.

I also happen to be in a life situation where I have a pretty good personal fit for engaging a lot with longtermism—I happen to find the ideas really fascinating, have enough flexibility that I can afford to do weird part-time remote work for EA organizations instead of remaining in a normal job like my former aerospace career, et cetera. I certainly would not advise any random person on the street to quit their job and try to start an AI Safety substack or something!!

I do think it’s good (at least for my own sanity) to stay at least a little grounded and make some donations to more straightforward neartermist stuff, rather than just spending all my time and effort on abstract longtermist ideas, even if I think the longtermist stuff is probably way better.

Overall, rather than the strong and precise claim that “you should definitely do longtermism, it’s 10,000x more important than anything else”, I’d rather make the weaker, broader claims that “you shouldn’t just dismiss longtermism out of hand; there is plausibly some very good stuff here” and that “regardless of what you think of longermism, I think you should definitely try to adopt more of an EA-style mindset in terms of being scope-sensitive and seeking out what problems seem most important/tractable/neglected, rather than seeing things too much through a framework of moral obligations and personal sacrifice, or being unduly influenced by whatever controversies or moral outrages are popular / getting the most news coverage / etc.”

That’s an interesting way to think about it! Unfortunately this is where the limits of my knowledge about the animal-welfare side of EA kick in, but you could probably find more info about these progest campaigns by searching some animal-welfare-related tags here on the Forum, or going to the sites of groups like Animal Ask or Hive that do ongoing work coordinating the field of animal activists, or by finding articles / podcast interviews with Lewis Bollard, who is the head grantmaker for this stuff at Open Philanthropy / Coefficient Giving, and has been thinking about the strategy of cage-free campaigns and related efforts for a very long time.

I’m not an expert about this, but my impression (from articles like this: https://coefficientgiving.org/research/why-are-the-us-corporate-cage-free-campaigns-succeeding/ , and websites like Animal Ask) is that the standard EA-style corporate campaign involves:

a relatively small number of organized activists (maybe, like, 10 − 100, not tens of thousands)...

...asking a corporation to commit to some relatively cheap, achievable set of reforms (like switching their chickens to larger cages or going cage-free, not like “you should all quit killing chickens and start a new company devoted to ecological restoration”)

...while also credibly threatening to launch a campaign of protests if the corporation refuses

Then rinse & repeat for additional corporations / additional incremental reforms (while also keeping an eye out to make sure that earlier promises actually get implemented).

My impression is that this works because the corporations decide that it’s less costly for them to implement the specific, limited, welfare-enhancing “ask” than to endure the reputational damage caused by a big public protest campaign. The efficacy doesn’t depend at all on a threat of boycott by the activists themselves. (After all, the activists are probably already 100% vegan, lol...)

You might reasonably say “okay, makes sense, but isn’t this just a clever way for a small group of activists to LEVERAGE the power of boycotts? the only reason the corporation is afraid of the threatened protest campaign is because they’re worried consumers will stop buying their products, right? so ultimately the activists’ power is deriving from the power of the mass public to make individual personal-consumption decisions”.

This might be sorta true, but I think there are some nuances:

i don’t think the theory of change is that activists would protest and this would kick off a large formal boycott—most people don’t ever participate in boycotts, etc. instead, I think the idea is that protests will create a vague haze of bad vibes and negative associations with a product (ie the protests will essentially be “negative advertisements”), which might push people away from buying even if they’re not self-consciously boycotting. (imagine you usually go to chipotle, but yesterday you saw a news story about protestors holding pictures of gross sad caged farmed chickens used by chipotle—yuck! this might tilt you towards going to a nearby mcdonalds or panda express instead that day, even though ethically it might make no sense if those companies use equally low-welfare factory-farmed chicken)

corporations apparently often seem much more afraid of negative PR than it seems they rationally ought to be based on how much their sales would realistically decline (ie, not much) as a result of some small protests. this suggests that much of the power of protests is flowing through additional channels that aren’t just the immediate impact on product sales

even if in a certain sense the cage-free activists’ strategy relies on something like a consumer boycott (but less formal than a literal boycott, more like “negative advertising”), that still indicates that it’s wise to pursue the leveraged activist strategy rather than the weaker strategy of just trying to be a good individual consumer and doing a ton of personal boycotts

in particular, a key part of the activists’ power comes from their ability to single out a random corporation and focus their energies on it for a limited period of time until the company agrees to the ask. this is the opposite of the OP’s diffuse strategy of boycotting everything a little bit (they’re just one individual) all the time

it’s also powerful that the activists can threaten big action versus no-action over one specific decision the corporation can make, thus creating maximum pressure on that decision. Contrast OP—if Nestle cleaned up their act in one or two areas, OP would probably still be boycotting them until they also cleaned up their act in some unspecified additional number of areas.

We’ve been talking about animal welfare, which, as some other commenters have notes, has a particularly direct connection to personal consumption, so the idea of something like a boycott at least kinda makes sense, and maybe activists’ power is ultimately in part derived from boycott-like mechanisms. But there are many political issues where the connection to consumer behavior is much more tenuous and indirect. Suppose you wanted to reduce healthcare costs in the USA—would it make sense to try and get people to boycott certain medical procedures (but people mostly get surgeries when they need them, not just on a whim) or insurers (but for most people this comes as a fixed part of their job’s benefits package)?? Similarly, if you’re a YIMBY trying to get more homes built, who do you boycott? The problem is really a policy issue of overly-restrictive zoning rules and laws like NEPA, not something you could hope to target by changing your individual consumption patterns. This YIMBY example might seem like a joke, but OP was seriously suggesting boycotting Nestle over the issue of California water shortages, which, like NIMBYism, is really mostly a policy failure caused by weird farm-bill subsidies and messed-up water-rights laws that incentivize water waste—how is pressure on Nestle, a european company, supposed to fix California’s busted agricultural laws?? Similarly, they mention boycotting coca-cola soda because coca-cola does business in israel. How is reduced sales for the coca-cola company supposed to change the decisions of Bibi Netanyahu and his ministers?? One might as well refuse to buy Lenovo laptops or Huawei phones in an attempt to pressure Xi Jinping to stop China’s ongoing nuclear-weapons buildup… surely there are more direct paths to impact here!

“Articulate a stronger defense of why they’re good?”

I’m no expert on animal-welfare stuff, but just thinking out loud, here are some benefits that I could imagine coming from this technology (not trying to weigh them up versus potential harms or prioritize which seem largest or anything like that):

You imagine negative PR consequences once we realize that animals might mostly be thinking about basic stuff like food and sex, but I picture that being only a small second-order consequence—the primary effect, I suspect, is that people’s empathy for animals might be greatly increased by realizing they think about stuff and communicate at all. The idea that animals (especially, like, whales) have sophisticated thoughts and communicate, and the intuition that they probably have valuable internal subjective experience, might both seem “obvious” to animal-welfare activists, but I think for most normal people globally, they either sorta believe that animals have feelings (but don’t think about this very much) or else explicitly believe that animals lack consciousness / can’t think like humans because they don’t have language / don’t have full human souls (if the person is religious) / etc. Hearing animals talk would, I expect, wake people up a little bit more to the idea that intelligence & consciousness exist on a spectrum and animals have some valuable experience (even if less so than humans).

In particular, I’m definitely picturing that the journalists covering such experiments are likely to be some combination of 1. environmentalists who like animals, 2. animal rights activists who like animals, 3. just think animals are cute and figure that a feel-good story portraying animals as sweet and cute will obviously do better numbers than a boring story complaining about how dumb animals are. So, with friendly media coverage, I expect the biggest news stories will be about the cutest / sweetest / most striking / saddest things that animals say, not the boring fact that they spend most of their time complaining about bodily needs just like humans do.