The Case for Making Professional Degrees Undergraduate Degrees

Cross-posted from Cold Button Issues

In the United States, there are many professions that are generally impossible to enter without both a graduate professional degree and an undergraduate degree, which may be in a completely unrelated field. Examples of these professions are physicians, attorneys, pharmacists, and physical therapists. Such requirements are unnecessary, as demonstrated by many developed countries that operate successfully without such a two-degree requirement. I estimate that these superfluous undergraduate degree requirements cost 730,000 person-years of work annually and foregone wages and salaries equal to 0.8% of all U.S. wages and salaries.

In the United States, occupational licensing is a state-level responsibility. These legal requirements for superfluous undergraduate degrees could be abolished in many states using ballot initiatives.

Using data on costs from recent statewide ballot initiatives, I estimate that this intervention would meet Open Philanthropy’s threshold for cost-effectiveness in some but not all states.

Why It’s Important

Research generally shows that adding additional educational requirements to enter professions produces no benefits.

Barrios (2021) showed that requiring accountants to achieve 150 semester hours instead of the traditional 120 hours is linked to fewer new accountants but not to higher ability in new accountants. Timmons and Mills (2018) showed that introducing optician licensing in the United States raised the salaries of opticians, but did not improve quality. In 2015, the Obama Administration’s Council of Economic Advisors concluded that:

Licensing laws also lead to higher prices for goods and services, with research showing effects on prices of between 3 and 16 percent. Moreover, in a number of other studies, licensing did not increase the quality of goods and services, suggesting that consumers are sometimes paying higher prices without getting improved goods or services.

More qualitatively, we can observe that these education requirements were considered unneeded in years past in the United States and are still considered unneeded in many countries around the world. For instance, a pharmacy degree used to be an undergraduate degree but has now been replaced by a professional doctorate in the United States and some other countries. In the United Kingdom, medical school is an undergraduate program. The American practice of requiring an undergraduate degree before entering many professional schools generates tremendous waste.

To estimate the lost years of work caused by required undergraduate degrees prior to professional education across the United States, I obtained the number of professional degrees granted in the 2018-2019 academic year from the National Center for Education Statistics that are generally used to enter licensed professions and that follow undergraduate degrees. I then multiplied the number of degrees granted by four, which represents the normative length of an undergraduate degree in the United States. This is not a precise estimate as some students take more or less than four years to graduate, some schools offer joint undergraduate-professional degrees to slightly speed the total time in education, some earn professional degrees but do not enter the profession, and some licenses require a certain number of credit hours rather than a specific degree.

To estimate the lost wages/salary, for each profession, I multiplied the estimated lost years of work by the median salary for that profession. I estimate that $67 billion in wages and salary is lost each year, which is roughly 0.8% of total U.S wages and salary. This also does not include any benefits such as employer-provided insurance or retirement benefits the employees would have earned, nor does it capture the benefit consumers would have enjoyed from a broader pool of professionals.

Given that occupational licensing appears to have little value in general and that it seems implausible that requiring, say, surgeons to acquire an undergraduate degree in economics or literature would improve surgical outcomes, the practice of requiring undergraduate education prior to entering professional school is tremendously wasteful.

Who Else Is Working on This?

As far as I know, no other groups or actors are currently working on the specific cause of actively abolishing the requirement to first earn a bachelor’s degree before pursuing many professional degrees.

However, there are groups working on reducing education requirements in certain fields and working to highlight the harms of restrictive occupational licensing. The Institute for Justice, a libertarian public interest law firm, produced the regularly cited and influential License to Work report about the extent of occupational licensing in the United States. The Institute for Justice also uses lawsuits to oppose, often successfully, educational requirements in fields such as hair braiding, eyebrow threading, and coffin sales. The Institute for Justice reported $38m in revenue in its recent 990. However, IOJ does not focus solely on occupational licensing reform. They also work on property rights, the First Amendment, educational choice, and economic liberty broadly.

Other groups that sometimes work to loosen educational requirements for professions are trade groups or professional associations themselves. Pharmacists have been able to win prescribing power in some states, encroaching on a traditional physician monopoly. Since pharmacists are less likely to complete a residency before starting their career, this on average reduces the amount of education required to prescribe drugs. Dental hygienists campaign for the right to practice without the supervision of a more highly educated dentist. I think these moves are good, but they’re limited in scope to the immediate benefit of certain professions.

Recent presidential administrations have also critiqued some elements of occupational licensing. For instance, the Obama administration endorsed reforms such as letting people with criminal records receive occupational licenses and suggested that it should be easier to transfer licenses between states or practice across state lines. President Trump and President Biden signaled support for similar reforms. None of these reforms took direct aim at unnecessary degrees and licensing laws are under state jurisdiction.

In conclusion, there are important actors working to liberalize occupational licensing rules. What is missing is people working for the wholesale elimination of required undergraduate education for the highest paid and most numerous occupations that results in the greatest economic waste.

How to Fix This

These requirements are laws which could be changed by their respective state legislatures. In states that allow for citizen-initiated ballot measures to enact statutes or constitutional amendments, these laws could be changed by ballot initiatives.

Roughly half of U.S. states allow voters to submit proposed language and signatures to the state government. Upon meeting a certain threshold, the proposed law or constitutional amendment appears on the ballot for voter approval. Initiatives routinely are enacted across the United States, although a substantial share of voter initiatives fail.

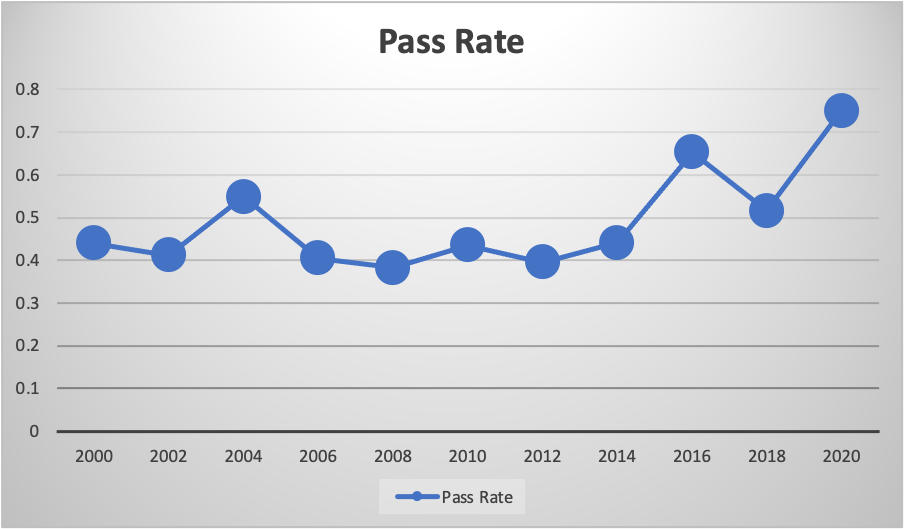

Pass rate of even-year initiatives, 2000-2021.

Data from National Conference of State Legislatures Statewide Ballot Measure Database

Estimated ROI

Not all states allow statewide ballot initiatives, and the cost of ballot access and cost of ballot initiative campaigns are not uniform across states. Campaigns in larger states cost more, as does the signature gathering process. However, the benefits of victory in such states are larger as well. I estimate the value of a state-wide ballot measure campaign in each state that allows for citizen-initiated ballot measures on this topic. Wyoming is excluded because it has not had any citizen-initiated ballot measures since 2010. Illinois is excluded because it allows for measures to change the structure of its government, but not to set public policy. Mississippi is excluded due to unavailable data on ballot access costs. All data is from Ballotpedia.

Assumption of BOTEC ROI Calculation

I assume that each state experiences lost wages due to required undergraduate degrees proportional to their share of the US population.

I assume the cost of ballot access is equal to the median cost of ballot access in citizen-initiated ballot measures in that state for the most recent year with data available from Ballotpedia.

I assume the cost of a campaign is equal to the median cost of campaigns in favor of citizen-initiated ballot measures in that state for the most recent year with data available from Ballotpedia.

I assume the odds of a successful campaign are 50%.

I assume a successful ballot initiative endures for ten years to account for the risk of reversal or some similar campaign that would occur without EA intervention.

According to my BOTEC, this intervention meets the 1,000 times bar that Open Philanthropy sets for itself, in some but not all states. States where my calculation suggests that this intervention would be cost effective include some of the larger states such as California, Florida, and Michigan.

If it were possible to reduce the costs of this intervention by EA funders for example by assuming other funders that value economic growth or economic liberty would also contribute to the costs of these ballot initiatives, then the expected ROI of this intervention would rise.

Conclusion

Abolishing the requirement for superfluous undergraduate education before pursuing a profession is important. Huge amounts of time and money are wasted fulfilling this obligation.

The issue is neglected and likely to remain that way. Professions, via their trade groups or professional associations, have an incentive to keep raising barriers to entry across the board and this will likely continue with more and more professions lengthening the amount of time required to enter their field. The costs, while large, are diffused across society and potential entrants to those fields. This is a classic example of a collective action problem. Philanthropy is one way to solve this problem. Because this initiative would go against the interests of powerful, entrenched interests, such as currently practicing physicians and attorneys as well as colleges and universities, I think it is unlikely state legislatures would amend their laws. Direct democracy seems a better approach than conventional lobbying.

The use of statewide ballot initiatives to end these requirements provides a clear path to solve this problem. Based on past costs of signature gathering, past costs of campaigns, and success rates for ballot initiatives, this plausibly clears the threshold for a cost-effective measure for Open Philanthropy.

Uncertainty about the cost effectiveness of this proposal could be alleviated by first testing a ballot initiative in a low-population state or by commissioning exploratory polls to see where such an initiative would be most popular.

This is cool; I often think about how much better the UK system is than the US when it comes to educating doctors.

I think my biggest quibble with your post is: “I assume the odds of a successful campaign are 50%.”

I would maybe revise that down to 5%? Professional organizations like the American Medical Association have their professions in a stranglehold; they have financial incentives to keep their profession difficult to access (eg allows them to demand higher wages), and they can easily manipulate the public by saying things like “Don’t you want a FULLY trained doctor? Not somebody who skipped undergraduate and went straight to medical school?”

A substantially more skeptical campaign success probability obviously lowers the expected ROI of this effort. But I wonder if other people who know more about politics are as skeptical as me.

All that being said, I would vote for your campaign if it came up on my state’s ballot!

feels possible to establish a decent base rate by looking at previous ballot initiatives by the mentioned firms and other similar ballot campaigns. I think it will vary a lot between licensing for a doctor vs hair braiding, and 50% might be reasonable for the latter.

Maybe I could get a more precise rate. The 50% assumption is close to the average success rate over the last 20 years.

There weren’t sufficiently similar ballot initiatives, IMO, to make me want to use a more specific reference class.

Did you factor in the length of the current programs vs. undergraduate programs that would replace them?

For example here in Israel an MD is an undergraduate program, but it takes 7 years to complete. There are some programs for people with an existing undergraduate degree, and those take 4 years (Edit: maybe 5) to complete. So it’s only a loss of 1 year (Edit: maybe 2) or even 0 years, depending on which undergraduate degrees they accept.