The Economic Benefits of Promoting and Protecting the Rights of LGBTQ+ Communities in Developing Countries

By Lee Crawfurd and Susannah Hares

Summary

Open Philanthropy should consider funding to promote and protect the rights of LGBTQ+ communities in developing countries. In around 70 countries (figure 1) it is still illegal—and in many cases punishable by death or imprisonment—to love who you want to. Half of these countries are in Africa and many are major recipients of aid and philanthropic money. Yet, in 2019⁄20 only 0.0004 percent of official development assistance was channelled to efforts supporting LGBTQ+ communities and only $52million was spent in sub-Saharan Africa (GPP).

Figure 1. Countries that criminalise same-sex relationships

Source Authors’ analysis from https://www.humandignitytrust.org/LGBTQ+-the-law/map-of-criminalisation/

The violation of the human rights of LGBTQ+ people is morally wrong and that justifies greater investment in its own right. But discrimination against LGBTQ+ people also damages economies through loss of productivity and labour and underinvestment in human capital. A conservative estimate of just some of the costs of discrimination against LGBTQ+ people (related to health and wages) sum to around 1 percent of GDP per year. At the high end of our ranges we arrive at striking benefit-cost ratios of over 200 in large economy countries (e.g. Nigeria) and 38 in smaller economies (e.g. Zambia) where homosexuality is illegal. Good evidence on the lived experiences of LGBTQ+ people limits our ability to confidently estimate the economic benefit of reducing discrimination and the actual economic cost of discrimination.

Major areas of uncertainty

The discrimination faced by LGBTQ+ people is challenging to quantify, because there are no existing multi-country datasets or in-country datasets within most countries (especially developing countries) on the lived experiences of LGBTQ+ people.

We may be substantially underestimating the economic impact of discrimination and we do not know if discrimination reduces more or less in years following law changes. We’ve used large ranges for both.

We don’t know enough to be able to say which interventions would work best to reduce discrimination. And we don’t have good cost estimates for the interventions we use in our analysis. Our analysis would be improved by some in depth case studies on how change in law and change in attitudes came about in developing countries (and how much that cost).

Importance

In recent years some countries have adopted more discriminatory legislation and have implemented intolerant actions toward LGBTQ+ communities and 57 countries and locations globally showed a decline in acceptance of LGBTQ+ people. The countries that were the least accepting of LGBTQ+ people in 2020 were Moldova, Ethiopia, Mauritania, Azerbaijan, and Zimbabwe, and they each became significantly less accepting since 2010. Nearly two thirds of African countries have laws that criminalise same-sex relationships. Some also criminalise LGBTQ+ advocacy. LGBTQ+ people across the continent suffer persistent violation of their human rights. A large number of people are affected: while we don’t have good data from developing countries, in the US and UK it is estimated that between 3 and 4 percent of people identify as LGBTQ+.

Badgett et al. (2019) describe how in recent decades the idea that inclusion of all groups in a population – especially women and other marginalised individuals – will promote shared prosperity and economic development has been increasingly embraced. They note that when LGBTQ+ people are denied full participation in society due to their identities their human rights are violated. Those exclusions and violations in turn are likely to have an adverse impact on a country’s level of economic development.

A conservative estimate of just some of the costs of discrimination against LGBTQ+ people (related to health and wages) sum to around 1 percent of GDP per year. We think this figure may be low, however in the absence of good evidence on the lived experience of LGBTQ+ people in most developing countries we are unable to estimate with more confidence. We therefore use a range of 0.1 percent to 1.7 percent of GDP per year for our calculations.

Tractability

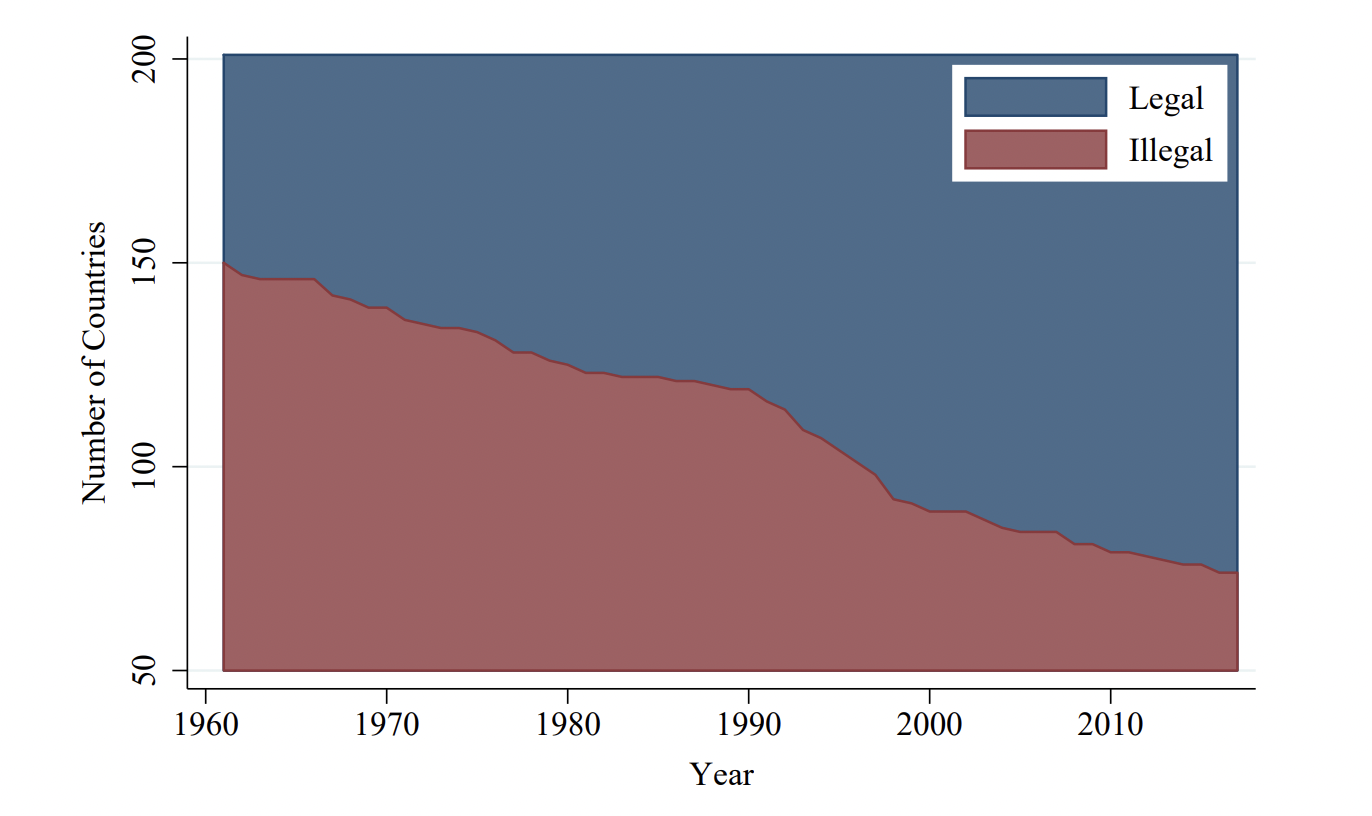

Despite the deterioration in LGBTQ+ rights in some countries described above, in the last 60 years the number of countries where same-sex relationships are legal has more than doubled (figure 2). 15 countries have decriminalised homosexuality in the last decade. In recent years Botswana and Angola have decriminalised same-sex relationships and sexual orientation is now a protected ground in Angola. In 2020 Gabon’s parliament reversed a 2019 law that had criminalised same-sex conduct for the first time. Laws are changing and, in countries where discriminatory laws and practices continue to exist, more funding could make a difference.

Figure 2. Legalisation over time

Philanthropic donors could fund efforts to promote LGBTQ+ right by bringing about change in norms or laws and changing public attitudes. Social movements and civil society organisations advocate for greater legal rights. Although the evidence is limited, some illustrative figures on costs and benefits are informative.

Take one example: the Human Dignity Trust, an organisation that “uses the law to defend the human rights of LGBTQ+ people globally”. Over the past decade they have spent less than $8.48 million in total. Their most credible direct claims of impact are Belize, where the Trust was responsible for some of the key successful legal arguments that led to decriminalisation of same sex relationships; and Northern Cyprus, where the Trust filed the court case that directly prompted the legislature to repeal the offending law. Applying the 1 percent of GDP per year estimate of the cost of discrimination to the economies of Belize and Northern Cyprus, leads to dollar amount of $60 million. (Note: Human Dignity Trust is not the only organisation engaged in litigation for LGBTQ+ rights. The Southern Africa Litigation Centre and the Eastern Caribbean Alliance for Diversity and Equality play similar roles in their respective regions. However, we have not looked at detailed information on their cost and impact.)

What effect would changing the law have on discrimination? One estimate suggests that a change in the law reduces the share of people who think that their society is a “bad place” for homosexuals by around 9 percent. If we took this to be a 9 percent reduction in the amount of discrimination, we arrive at a dollar benefit of more than $5 million. Even if this was all the Human Dignity Trust had achieved in its ten years (changing the law in Belize and Northern Cyprus), that success alone could produce an annual return on investment of 62 percent. Even focusing very narrowly on the economic case and leaving aside the more fundamental issue of basic dignity and human rights, as well as other legal topics in addition to decriminalisation that the Trust has successfully advanced, that is a promising investment.

It becomes more difficult to be precise about economic benefits in countries with larger economies, especially where attitudes toward safe-sex relationships are very negative. In our examples above, from Belize and Northern Cyprus, the Human Dignity Trust supported litigation to change laws or to prevent the repeal of laws. In Cyprus, around 35 percent of citizens believed homosexuality was never justifiable in 2011 (WVS 2011) three years before the legal change in 2014. In a 2013 poll in Belize—three years before homosexuality was decriminalised -- around 70 percent of citizens said they tolerate or accept homosexuals. But in Nigeria, where same-sex relationships remain illegal, 80 percent citizens believe that homosexuality is never justiable (WVS 2018). So we think it is probably wise to assume that changing the law in Nigeria is a much bigger task in 2022 than it was in Cyprus in 2014 - more expensive and with a high chance of failure.

We’ve suggested that you might spend $100 million on litigation in Nigeria to achieve legal reform. If you were successful, the economic benefits are striking - we arrive at a dollar benefit estimate of between $23million and over $1billion and a benefit cost ratio of between 5 and over 200. Applying the same calculations to a smaller economy (we used Zambia as our example) we get an annual dollar benefit estimate of between $1million and $23million and a benefit cost ratio of between 1 and 38. These ranges are large and they reflect our lack of confidence in estimates on the cost of discrimation and the reduction in discrimination we might see if laws did change. Our calculations including the ranges are in this spreadsheet.

Above we used litigation as an example of how we could change laws and reduce discrimination against LGBTQ+ people. But litigation is not the only way we might do this. And we don’t know if it’s the most effective or feasible way. It’s possible that litigation only works if there is a baseline level of tolerance of same-sex relationships. So we have also included calculations for two other types of intervention: mass media campaigns and more intense interventions:

Mass media campaigns. We used $75million as the possible cost of an effective mass media campaign for Zambia and $300million for Nigeria. We don’t know if these figures are realistic but with more time we could do more detailed costing estimates and analysis on how effective such a campaign might be. But with those figures, we come to a benefit cost ratio of between 0.3 and 13 for Zambia and between 1.6 and 70 for Nigeria.

More intense interventions. We assumed a cost of $10 per adult population (over 15). This figure is a guess but could be feasible based on other targeted attitude change interventions (e.g. here and assuming some economies of scale). With that cost input we arrive at a benefit cost ratio of between 0.2 and 10 for Zambia and 0.4 and 19 for Nigeria.

The calculations for these additional types of interventions are in the same spreadsheet. The BCRs of all three intervention types are summarised in the table below. “High estimate” indicates the high end of our ranges for the cost of discrimination and the reduction in discrimination following law change. “Low estimate” indicates the low end of our ranges for both.

Table 1. BCR estimates for three types of intervention

Litigation BCR | Mass Media BCR | Targeted Intervention BCR | |

| Nigeria (high estimate) | 211 | 70 | 18.9 |

| Nigeria (central estimate) | 77 | 25.8 | 7.0 |

| Nigeria (low estimate) | 5 | 1.6 | 0.4 |

| Zambia (high estimate) | 38 | 13 | 10 |

| Zambia (central estimate) | 14 | 4.6 | 3.5 |

| Zambia (low estimate) | 1 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

Neglectedness

Funding for the protection and promotion of LGBTQ+ rights, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, is low.

In 2019/2020 $576 million was spent on LGBTQ+ programmes globally. 30 percent of this come from foundation donors. When excluding US funders, the top foundation funders are Open Society Foundations and Elton John AIDS Foundation. In 2019/2020 government donors and multilateral agencies spent $138million development aid on LGBTQ+ communities, with the top donors being Netherlands, Sweden and Canada. Only 0.0004 percent of Official Development Assistance (ODA) was spent on LGBTQ+ programmes in 2019/2020 (GPP). And just $52million was spent in sub-Saharan Africa in 2019⁄20, where rights of LGBTQ+ people are most violated.

What could a new philanthropist do?

Spending more money to tackle violence and discrimination against LGBTQI people in developing countries would be a good use of philanthropic money. All else equal, aid is more effective when targeted at the most vulnerable people, so it makes sense to put a positive weight on LGBTQ+ communities in allocation decisions. Here are some examples of how money could be spent:

Fund advocacy organisations who aim to change discriminatory laws

Philanthropic donors can use aid to promote LGBTQ+ causes by funding efforts to bring about change in norms, policies or laws that advance and protect LGBT+ people’s rights and inclusion. This would include the removal of negative legislation, decriminalisation of same-sex behaviour and support for actively positive legislation for LGBTQ+ people. Social movements and civil society organisations that advocate for greater legal rights include the Human Dignity Trust and Amnesty International. Our earlier example of the Human Dignity Trust lays out the economic case for investing in changing laws.

However, in practice, authorities in many countries that have signed international treaties committing them to protect human rights continue to rule with legislation that singles out and discriminates against individuals for their sexual orientation. So while changing the law is important, it is probably not enough.

Fund advocacy organisations who aim to change public attitudes

Research suggests that pride events do have some effect on public attitudes, even in conservative societies. For example, support for pride in Sarajevo increased by 9 percentage points after the march, compared with no change in other Bosnian cities over the same period that did not have marches.

Fund organisations to help LGBTQ+ people access basic services and opportunities

Whether or not it is legal, LGBTQ+ people face barriers to services or opportunities. This includes denial of health services to people who identify as a different gender to their birth sex, discrimination in the labour market, or lower access to education or social services. Each barrier means that LGBTQ+ people have fewer opportunities to make a living and suffer worse health and education outcomes. We have not had time to research organisations that have a strong track record of reducing barriers to services for LGBTQ+ people (but would be happy to if OP had an interest in this topic).

Fund more research on particular interventions that might be successful in helping change laws and reduce discrimination.

Better evidence on the experiences of LGBTQ+ people would enable better estimates of the total cost of discrimination and exclusion of LGBTQ+ people. We also need better evaluation of efforts to reduce discrimination and barriers to services.

Appendix

A few organisations working in this area

All Out—Global campaigns group, funds campaigns and local community organisations

Amnesty International—public campaigns and behind-the-scenes lobbying

Commonwealth Equality Network—Umbrella organisation for national advocacy groups

Human Dignity Trust—focuses on strategic litigation challenging the criminalisation of homosexuality around the world

Southern Africa Litigation Centre - focuses on strategic litigation challenging the criminalisation of homosexuality in Southern Africa

Eastern Caribbean Alliance for Diversity and Equality - focuses on strategic litigation challenging the criminalisation of homosexuality in the Caribbean region.

OutRight Action International—promotes human rights for LGBTIQ people everywhere through three programme areas: advocacy, research and movement-resourcing.

Peter Tatchell Foundation—seeks to raise awareness, understanding, protection and implementation of human rights, in the UK and worldwide. This involves research, education, advice, casework, publicity and advocacy.

Westminster Foundation for Democracy—WFD’s inclusion programme is funded by the FCDO. It conducts research and supports local community organisations.

HIVOS—challenge and reform the legislative framework that criminalises and stigmatises LGBTI+ people by advocating for a liberal interpretation of relevant laws, including arrest procedures and the definition of privacy rights during arrests, while supporting the expansion of the LGBTI+ movement and increasing accessibility of health-related and legal services to LGBTI+ individuals

Note: we have not researched these organisations extensively and do not know how effective they are.

I’ll just like to mention Rainbow Railroad, a Canadian group focused on helping queer people in unsafe circumstances get to safer countries

This is a really important topic. There are a few problems.

Your article mostly focuses on gay people. They make up a tiny portion amoung a community that includes transgender, nonbinary, intersex, asexual, bisexual, pansexual, polyamourous and more people. In areas where the LGBT+ community is widely accepted, there are extrememly high portions of the populations that identify as LGBT+. Having statistics about 30% of the population is very different than having statistics about 5% of the population. Many older survey have lots of deeply closeted people. You need to intentionally include the entire community.

LGBT+ is a very western concept. You need to intentionally include cultures and cultural identities in the countries you highlighted that don’t have western concepts of gender and sexuality.

Obviously colonization, imperialism, and coersive conversion to Christianity is the cause of these issues. One very important issue to consider today are radical Chrisitans from the US that are actively advocating for violence and pushing for this bad legislation. You can’t solve this issue without finding a way to ban these people from doing that. They mostly do it in person so there’d need to be travel bans for these people.