New cause area: maternal morbidity

Summary

What is the problem?

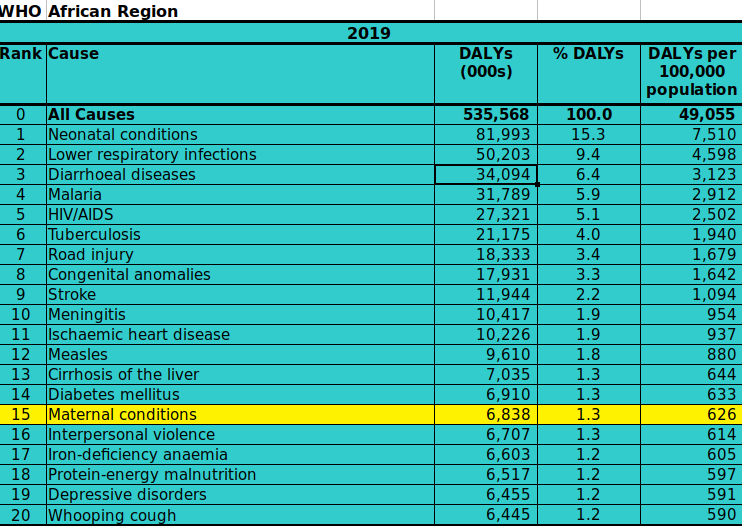

Maternal morbidity is a leading cause of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) worldwide and particularly in low and middle income countries (LMIC), with maternal conditions one of the top 20 causes of DALYs in WHO’s Africa region.[1] Maternal morbidity is defined by the WHO as “any health condition attributed to and/or aggravated by pregnancy and childbirth that has a negative impact on the woman’s wellbeing”[2] encompassing “near-miss” events in which a woman could have died (for example, haemorrhage) as well as chronic (for example, postpartum depression) or self-limiting (for example, nausea and vomiting during pregnancy) conditions. Anaemia and depression may be the most common conditions that contribute to overall maternal morbidity, with obstructed labour being the greatest source of DALYs, mainly due to resulting obstetric fistulas which I will discuss in more detail below.[3]

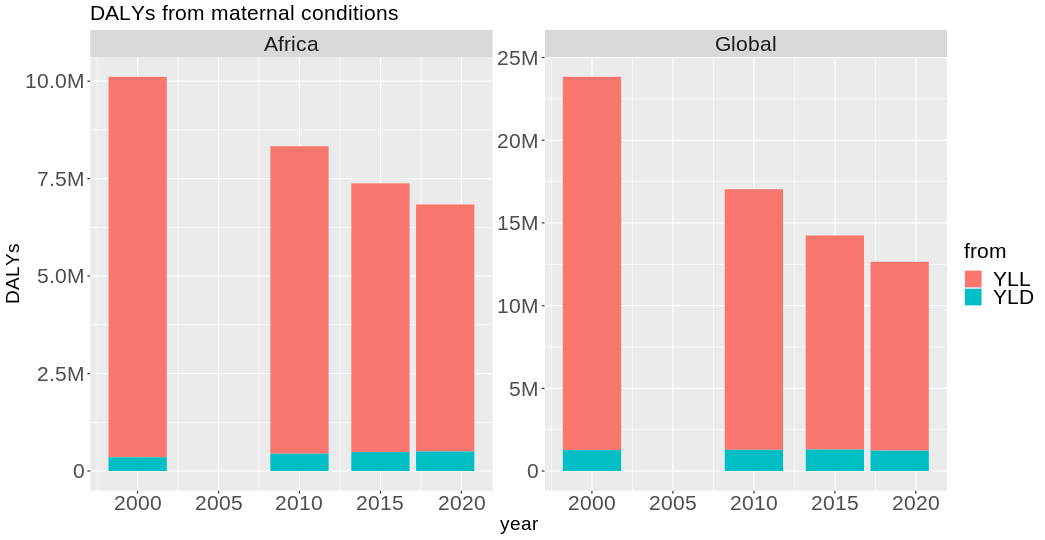

Absolute numbers of DALYs due to maternal causes have been falling since 2000 due to fewer years of life lost (YLL), but the total incidence of maternal disorders and number of years lived with disability (YLD) have not seen a similar trend and increased in many countries.[4] Years lived with disability now contribute about twice as much to the overall DALYs than in 2000, reflecting the fact that little progress has been made on morbidity as opposed to mortality.[1]

The above figures from the WHO global burden of disease study omit many morbidities (including dyspareunia, genital prolapse, perineal tears, maternal mental health, urinary tract infections, nausea and vomiting, and vulvar disruption)[5], making them an under-estimate of the true burden (even aside from the socio-economic consequences which are not captured by DALY measurements).

One indication of the area’s neglect is that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) explicitly include maternal mortality but not morbidity as a target (under SDG 3, “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages”).[6] What’s more, we still don’t have a standard definiton of maternal morbidity or national surveillance studies in most countries. Standardising the definition and developing further targets and indicators could be an important first step in improving global strategies around maternal health.

What could a new philanthropist do?

Funding could be directed towards:

The adoption of a standard definition of maternal morbidity

Lobbying for the inclusion of maternal morbidity in global development goals

Surveillance projects in LMIC with a preventative focus, to accurately identify burden and causes

Provision of care in LMIC known to effectively target specific causes of maternal morbidities

Research into poorly understood maternal conditions

This is a very broad and complex area. The achievement of aims 2 and 3 depends on the achievement of 1, whereas 4 and 5 could proceed largely independently of those. A funder may therefore wish to focus either on the foundational work involved in the first 3 of these suggestions, or on one of the latter two. If the latter, I will make some more detailed remarks about two specific conditions that I think would be good candidates for spending: obstetric fistula and nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP).

Importance

Overall

In 2012, estimates suggested that there were 20 million new incidences of long-term disabilities due to maternity every year and there were 1.4 million incidences of severe acute maternal morbidity (SAMM) or maternal “near-miss” events (MNM).[7]

It is hard to find estimates for the number of people living with chronic disability from maternal causes, but by way of comparison, these incidence figures suggest it is of a higher order of magnitude than HIV, given 1.5 million new incidences of HIV annually.[8]

In the WHO Africa region, maternal conditions are a top 20 cause of DALYs as of 2019.[1]

While global trends do suggest that the absolute number of DALYs resulting from maternity is declining, due to effective targeting of maternal mortality rates, the number of years lived with disabilities has remained more or less constant globally, increasing in Africa.[1]

These estimates are likely to be under-estimates of the true burden in several ways. Firstly, they straight-forwardly fail to capture the true burden in terms of DALYs by omitting many conditions, including dyspareunia, genital prolapse, and poor mental health.[5] A 2022 study estimates the prevalence of perinatal mood disorders in LMIC at 20%,[9] so the burden of those conditions alone are significant. Efforts to quantify the extent of severe maternal morbidity (SMM) or maternal “near-miss” (MNM) events as defined by the WHO have struggled because of the lack of a standard definition across studies.[10]

Secondly, the effects of maternal morbidity go beyond the DALY burden and include women’s ability to care for their children and to participate in the economy and society more broadly. Maternal morbidity therefore has a significant bearing on infant mortality and outcomes, gender equality, and poverty.[11] In patriarchal societies, women who suffer from chronic maternal disability are likely to suffer from emotional, physical and sexual abuse, and are socially shamed due to misconceptions that disabilities like uterine prolapse or fistula result from their own historic sexual behaviour.[12]

“Results of interviews showed that exposure to emotional abuse was almost universal, and most women were sexually abused. The common triggers for violence were the inability of the woman to perform household chores and to satisfy her husband’s sexual demands.”[12]

The impact of maternal morbidity is greatest in LMIC but is significant in HIC as well. For example, the cost of maternal morbidity in the US was estimated to be $32.3 billion for all births in 2019[13]. Common conditions affecting women in the UK a year after giving birth include pelvic pain (1 in 5)[14], incontinence (1 in 4)[15] and depression (1 in 10).[16] There is a significant gap in the amount of sick leave taken by men and women in HIC and half of this is attributable to pregnancy.[17] Scandinavian studies place the median amount of sick leave taken per pregnancy at 8 weeks.[18]

Although harder to quantify, I want to emphasise the impact of maternal morbidity on gender inequality. Maternity, construed broadly as pregnancy, childbirth and childcare, is surely the single biggest contributor to unequal gender relations in all settings. The average fertility rate in Africa is 4.5 children per woman.[19] That’s over 3 years of a woman’s life spent pregnant, a condition known to impair physical and mental quality of life, even before the risk of death, injury and burden of childcare is taken into account. Even in a highly developed country like the UK, 80% of women have at least one child.[20] The very worst childbirth outcomes are rare but this almost certainly involves weeks to months of time off work for pregnancy with nausea, pain or other impairments, with a high likelihood of at least one postpartum affliction such as incontinence, vaginal pain, depression or anxiety. The health consequences of pregnancy and childbirth are an additional burden to the social and economic costs that motherhood imposes on women, who do 75% of childcare worldwide and are not economically remunerated for this work.[21]

Obstetric Fistula

3 million people are estimated to be living with obstetric fistula.[22] This is nearly 1⁄10 of the number of people living with HIV.[8] Fistula is a condition that causes the leaking of urine and faeces. The constant incontinence results in poor physical quality of life with pain, infections and genital sores, and typically results in social ostracisation, marital breakdown, loss of livelihood and deepening poverty.[12] [23] [24] This is a prevalent condition with particularly severe consequences for physical and mental quality of life.

Less severe forms of incontinence are incredibly prevalent, with urinary incontinence affecting 1 in 3 postpartum women[25] and some level of anal incontinence 1 in 4.[26] The actual effect on quality of life is quite variable here, but the high prevalence warrants some attention.

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy

The global prevalence of NVP amongst pregnant women is estimated to be 70%.[27] Estimates of prevalence for the most severe form of NVP, hyperemesis gravidarum (HG), vary, likely due to under-reporting and the lack of a standard definition, but are usually placed between 1% and 10%[28] with moderate NVP being much more common, accounting for about half of cases.[29][30] Moderate to severe NVP has a very large effect on quality of life, with physical quality of life impeded to a similar degree as for breast cancer or heart attack sufferers and mental quality of life scores comparable to postpartum depression.[30] Although self-limiting, in that it resolves after childbirth, research on psychosocial effects of HG suggest lasting harms including relationship breakdown and limiting family size.[31]

Neglectedness

Overall

The neglect of maternal morbidity as a cause area in and of itself is evident from the lack of targets and indicators around it. Although an important contributor to several SDG goals, maternal morbidity as an explicit target is absent, and an issue throughout the existing literature is the lack of a standard definition or standard tools for measurement.

Fairly recently, in 2018, the WHO published the output of a 5 year working group, the Maternal Morbidity Working Group (MMWG) which includes a proposed definition and framework for measurement.[32] This paper has been cited 22 times and marks some progress on the issue of a shared set of definitions and metrics, but does not seem to have solved the problem of standardising indicators and measurement tools. The WHO definition of MNM has seen more adoption in LMIC than in HIC, prompting the suggestion that it may not be as appropriate in all settings, and that further work on standardisation is required.[33] The creation of separate tools for LMIC and HIC may be warranted.

Different measurement tools result in substantially different MNM rates[33], so standardisation is a prerequisite for the setting and monitoring of targets. Many HIC have conducted national surveillance studies but often use different definitions of MNM or SMM and have been criticised for lacking a focus on prevention.[34] While WHO standards have been taken up more in LMIC, there is still much more limited data in those settings overall. There are some examples of partial surveillance studies using the WHO definitions of MNM in lower income settings that demonstrate the feasibility of conducting such research at a national level.[35][36]

Working out how much is being spent on maternal morbidity in total is quite difficult, given the large number of ways maternal morbidity can present. Many initiatives that target maternal mortality or neonatal mortality (targets 3.1 and 3.2 of the SDG[6]), and issues of gender equality such as preventing child marriage (target 5.3 of the SDG[37]) will have effects on maternal morbidity even where the latter is not an explicit target. $4.9 billion was spent on maternal health globally in 2020.[38]

Obstetric fistula

Obstetric fistula has received some attention, with several charities working on this area: https://fistulafoundation.org/, https://www.freedomfromfistula.org.uk/, and https://worldwidefistulafund.org/ . In 2020, the United Nations Population Fund (UNPFA) passed a UN resolution setting a target to end fistula by 2030[39] and in 2022 pledged $7 million to a Sierra Leone initiative, and in 2019 the Fistula Foundation spent $12 million (82% of that on programs).[40] Since 3 million people are estimated to be living with obstetric fistula this seems like an underspend (by way of comparison, $9 billion was spent on HIV), but arguably this is not the most neglected maternal condition.

Milder forms of incontinence are more neglected. Further research would be needed to assess whether their high prevalence makes them worth paying more attention to, despite not having such severe effects on quality of life.

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy

There are also still many maternal conditions that are poorly understood. Despite affecting 70% of pregnant women there is very little research into NVP. There are two dedicated charities in this area, Hyperemesis Education and Research Foundation which declares annual expenses of under $200,000[41] and Pregnancy Sickness Support which had an income of £134,000 in 2021.[42] That such a small pot of funding is dedicated to NVP suggests it is receiving significantly less attention that it deserves.

NVP that falls short of HG is even more neglected than HG. The organisations mentioned above often emphasise the difference between HG and “morning sickness”, as seen on the homepage of Pregnancy Sickness Support:

Emphasising the severity of HG, which is life-threatening and often requires hospitalisation, is likely a strategy to bring more attention to this neglected area, but is a real misrepresentation of the true nature of pregnancy sickness. “Morning sickness” is a complete misnomer as sickness occurs at any time of day[43], and even so-called “moderate” pregnancy sickness has a huge impact on quality of life and ability to work or care for dependents.[44][45]

Tractability

Overall

Global maternal mortality rates have fallen[1] and this seems like a cause for optimism about our ability to improve maternal health more broadly. Broadly speaking, it seems like progress could be made by allocating funding towards:

The global adoption of standardised definitions. The WHO MMWG 2018 framework[32] provides a starting point for this, but further work is needed to identify the ways in which it has been modified in practice, and to determine whether it is universally applicable[33]

Lobbying for explicit inclusion of maternal morbidity targets in global development goals, or the setting of specific targets outside of these goals (like the target to end fistula by 2030)

National surveillance studies with a preventative focus in LMIC

Improving the standards and breadth of the existing data and setting global strategies could be a focus for a new funder. The problem of standardising data does look like a difficult one, given the limited success of the WHO MMWG framework, but it seems like uptake of this might be most achievable in LMIC. Existing feasibility studies for using the WHO definitions to monitor MNM can be used as a model for designing national surveillance studies in these settings.[36][35]

As well as these high level goals, funding could be directed towards specific conditions where there are well-defined research questions or well-understood interventions. Again I will highlight obstetric fistula and NVP; the former is something that has been eliminated in HIC and has proven, cost-effective, interventions, and the latter has many well-defined research questions.

Obstetric fistula

Surgery to correct fistula in low income settings has been estimated to cost between $40 per DALY and $54 per DALY averted[46][47]. Although studies of this kind can be optimistic, this is a very promising indicator that it is cost-effective. It is a particularly severe condition giving rise to a high number of DALYs[48] and with many harmful social and economic consequences[49] for sufferers and this is likely the reason that it has received more attention than some other conditions. The very low incidence and prevalence of fistula in HIC point to how tractable this problem is.

Fistula is a consequence of obstructed labour, which also contributes to a number of other conditions such as uterine rupture and gential prolapse. Monitoring during pregnancy and early presentation to hospital during labour lower the chance of obstructed labour occuring and increasing such monitoring is a key component of any maternal health strategy.[50] The broad aim of improving antenatal care obviously speaks to all maternal morbidities as well as causes of mortality, and it is hard to assess how tractable this is in and of itself. Aside from resources constraints, obstacles include lack of education, traditional beliefs/superstitions, and women’s reliance on husbands for decision making.[51] Universal access to antenatal care was a target under the Millenium Development Goals (MDG) and the failure of significant progress in this area perhaps points to it being less tractable than other interventions.[52]

Other neglected conditions with similar causes and treatments to fistula include uterine rupture, and genital and uterine prolapse.[53] Like fistula, reducing obstructed labour will help reduce the incidence of these, and like with fistula, there are surgical interventions to repair these injuries. Unfortunately, there is limited cost effectiveness data for surgical interventions for vaginal or uterine prolapse and all that do exist are in high income settings. In the US, such surgical interventions are considered cost effective at under $50,000 per QALY gained[54], but RCTs are needed with economic analysis in low income settings.

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy

The above examples seem like low-hanging fruit with well-specified outcomes. Funding research into less well understood conditions will have less predictable outcomes but could be very impactful. Given the incredibly high prevalence, there is very little research into severe NVP and HG. In 2020, a multi-national HG priority setting partnership identified a list of research priorities, and a new funder could offer grants for research funding based on these questions.[55] Directing further funding to the Hyperemesis Education and Research Foundation would also be a straight-forward way to further the research agenda.

It is rather hard to estimate the tractability of improving treatments for NVP, as so little funding has been directed to researching it thus far. The difficulties of running clinical trials on pregnant women may be a barrier when it comes to developing new treatments, but the scope for progress seems to be large given the extent of our current ignorance about this condition.

Key Uncertainties

Given the absence of a widely used standard definition, what is the true prevalence and burden of maternal morbidity worldwide? How tractable is the project to standardise the definition, given its lack of success so far?

To what extent are maternal mortality targets sufficient to target maternal morbidity, since improvements in care will often target both? This will be the case for some, especially acute, causes of morbidity (but the improvements in mortality rate without corresponding reductions in YLD suggest this is not sufficient).

How much attention should also be given to high income countries (HIC)? For example, maternal morbidity (as well as mortality) is trending upwards in the US[56] and likely to be made much worse by recent changes to abortion legislation[57], with burden disproportionately located within racial minorities.[58] The economic cost of pregnancy alone in HIC could be very high—studies suggest that women take a median of 8 weeks sick leave during pregnancy[18] and that half of the observed gender gap in sick leave is attributable to pregnancy.[17] Higher quality data is more readily available in HIC so perhaps better suited for certain research questions.

Is all-cause maternal morbidity too broad a cause area to fund? More detailed cases could be made for many individual conditions, such as the two I’ve focused on above—obstetric fistula in LMIC and nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) but also many others.

Thanks: to Diana Fleischman, Marielle Volz, Julia Sorensen, Robert Wiblin and Rowena Hill for comments on earlier drafts of this report.

This is interesting, thanks! It’s surprising that morbidity hasn’t changed much despite progress on mortality, given significant overlap in their prevention/treatment. I think progress on maternal mortality could increase morbidity estimates because women are surviving with near-miss or chronic complications rather than dying. How big/real do you think this effect is?

Great question. It certainly seems likely that this may effect may be contributing to the trend in some places. But hard to answer definitively because of the lack of standard definition and lack of monitoring of near-miss events in general. There are also other reasons why morbidity could be rising in some contexts—e.g. rising obesity levels and older age of mothers and in principle it could also be that most of the gains in mortality have come from reducing mortality causes that, if survived, don’t typically cause chronic disability, so don’t give to rise to many YLD. Major causes of mortality are haemorrhage, sepsis, high blood pressure and obstructed labour, and I think the last one contributes most of the YLD.

It would be really interesting to understand this more. The WHO is encouraging HIC to focus much more on near-miss events now that mortality rates are low, and much more data is needed overall!