Climate Risk Financial Regulation in the United Kingdom

This case study was produced in response to Holden Karnofsky’s call for case studies of regulations that could be relevant to future AI safety regulations.

The case study itself does not directly discuss its relevance to AI safety. However, I believe that many of the learnings from the creation of climate risk financial regulation in the UK can be applied to AI regulation.

Key Points

Principles-based regulation can effectively cover fast-evolving areas where defining concrete rules referencing implementation details is challenging.

Offering guidance in the form of concrete examples of compliance and non-compliance can help illustrate rules and principles more effectively than just abstract discussion. Providing example cases can also help people find analogies to their situation in the regulation, making decision-making easier.

When considering Climate Risk, the United Kingdom (UK) regulators separate this into physical and transition risks.

Physical risks are risks caused by actual changes to the climate, such as extreme weather events (e.g., floods, heatwaves) and longer-term changes to our climate (e.g., sea level rise)

Transition risks are financial risks caused by governments, industries, and consumers’ changes to pursue a greener world. For example, in light of green investing trends, holding much equity in fossil fuel companies could be unnecessarily risky in capital management.

The Bank of England (BoE) runs a Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario (CBES) to simulate how the largest UK banks and insurers would respond to three climate scenarios.

Early Action: Transition to a net-zero economy starts immediately, resulting in reduced emissions by 2050 and slight global warming to 1.8°C, with a small overall impact on GDP growth.

Late Action: Policies are delayed until 2031, leading to sudden and disruptive emissions reduction, causing significant short-term macroeconomic disruption but achieving a 1.8°C warming limit by 2050.

No Additional Action: The absence of new climate policies leads to a temperature rise of 3.3°C, causing permanent impacts on living conditions, infrastructure, and GDP growth, worsening and potentially irreversible effects later in the century.

The 2021 CBES enabled better forecasts of the effects of climate change and shifts to greener energy sources on the UK financial system, as firms were forced to estimate, model, and disclose their climate risk strategy and current exposure levels.

The BoE’s Climate Change Adaptation Report mentions the differences between Capability Gaps and Regime Gaps.

Capability gaps refer to the technical challenges in identifying and measuring climate risks, even within existing frameworks. This could be caused by insufficient detailed data from firms about their climate risks or limitations in modeling techniques that accurately incorporate and estimate the impact of climate factors.

Regime gaps denote the difficulties in capturing climate risks due to the design and methodologies used in typical capital frameworks. Microprudential capital frameworks, which typically use historical data for short-term risk predictions, might underestimate future climate risks that emerge over longer horizons.

Introduction to Financial Regulation

The financial industry is critical to the functioning of the economy, and failures within this sector can precipitate widespread impacts. Protecting all stakeholders—companies, investors, and consumers—poses a high-stakes challenge. Establishing robust laws, standards, and requirements to safeguard service providers and users is crucial.

Compliance with these regulatory measures is actively encouraged through deterrents such as legal penalties, including imprisonment and fines, and by highlighting the inherent benefits of compliance. In doing so, governments aim to cultivate a healthy financial ecosystem that promotes mutual benefits for all participants.

New financial regulation is usually introduced for one of two reasons: to address risks and to promote benefits. For instance, regulations like the EU Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) were introduced to mitigate risks such as market abuse and fraud. In contrast, others, like the UK Open Banking directives, were designed to foster certain benefits, such as promoting competition, innovation, and customer empowerment in the banking and financial sectors.

While financial regulation can be reactive and proactive, it is often reactive. For example, the 1929 stock market crash in the United States (US) led to regulations like the US Securities Act. The 2008 financial crisis led to multiple new regulations worldwide, such as the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform in the US and EMIR reporting regulation in the EU.

There exist different regulatory approaches, partially influenced by cultural factors. The US, for instance, adopts a rules-based approach with rule-heavy regulations such as the Commodity Exchange Act, which sets out an extensive regulatory framework for commodity futures and swaps markets. Its scope covers a vast range of commodities and market participants with detailed regulations on business conduct, registration, reporting, and more.

The UK, on the other hand, uses a more principles-based approach with fewer explicit rules. This approach allows regulators to enforce principles even if a specific rule is not in place.

This report from the UK’s Office of Communication (OfCom) gives a good high-level description of principles-based vs. rules-based approaches to regulation, contrasting them in the context of promoting competition in digital markets. For example, it states:

The UK Government has consulted on an approach which codifies the objectives of regulation in legislation, complemented with legally binding principles that firms in scope should adhere to. In contrast, the US and EU proposals are more akin to a set of legislative rules which describe what online platforms in scope should or should not do, with a regulator that enforces these rules in court or through an administrative approach respectively.

The choice between rules and principles is not unique to the debate on how to regulate digital markets. To the contrary, it is a key factor that defines any regulatory approach.

Rules can also become outdated in highly dynamic markets. Changes in market context can create scope for new harmful conduct that is not captured by existing rules, or developments in business practices can (sometimes intentionally) allow firms to circumvent these rules. For example, if the type of data required to compete in a market changes over time due to technological progress, then prescriptive rules on which data an incumbent with substantial and entrenched market power should share with challengers may not remain effective at promoting competition over time.

Principles

Principles in financial regulation are high-level, overarching objectives that the regulatory framework seeks to achieve. They are usually broad and relatively abstract, which means they can be applied to a wide range of specific situations.

Like the tenets of virtue ethics, where general and abstract notions are set to guide moral conduct, principles can provide a moral or ethical guidepost, helping to shape the culture and values of financial institutions.

However, due to their broad nature, they often need more specificity to govern all detailed actions within a financial institution. They serve as the foundational underpinning for more detailed guidance and rules.

To see examples of Principles, we can take a look at the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) ’s Principles for Business:

| Integrity | A firm must conduct its business with integrity. |

| Skill, care and diligence | A firm must conduct its business with due skill, care and diligence. |

| Management and control | A firm must take reasonable care to organise and control its affairs responsibly and effectively, with adequate risk management systems. |

| Financial prudence | A firm must maintain adequate financial resources. |

| Market conduct | A firm must observe proper standards of market conduct. |

| Customers’ interests | A firm must pay due regard to the interests of its customers and treat them fairly. |

| Communications with clients | A firm must pay due regard to the information needs of its clients, and communicate information to them in a way which is clear, fair and not misleading. |

| Conflicts of interest | A firm must manage conflicts of interest fairly, both between itself and its customers and between a customer and another client. |

| Customers: relationships of trust | A firm must take reasonable care to ensure the suitability of its advice and discretionary decisions for any customer who is entitled to rely upon its judgment. |

| Clients’ assets | A firm must arrange adequate protection for clients’ assets when it is responsible for them. |

| Relations with regulators | A firm must deal with its regulators in an open and cooperative way, and must disclose to the FCA appropriately anything relating to the firm of which that regulator would reasonably expect notice. |

As stated in this OfCom report

It can be beneficial to require that firms adhere to broadly stated principles that describe the objective of regulation as opposed to specifying prescriptive rules that they should follow. Such a ‘principles-based’ approach also allows companies greater flexibility on how to behave to achieve these stated objectives. This can be particularly attractive where firms are better placed to identify the best approach to achieve desired outcomes, or where their actions are only harmful in some circumstances.

Guidance

‘Guidance’ refers to non-binding advice or recommendations given by regulatory authorities to help financial institutions understand how to comply with specific regulatory requirements.

The FCA Handbook contains extensive guidance alongside the rules and principles listed. This includes a combination of:

Examples of behavior that violates the rule

Examples of behavior that does not violate the rule (particularly edge cases or potentially confusing scenarios)

Suggestions of ways to prevent breaching the rule

Clarification on what is meant by various terms and phrases in the rule

For example, the FCA guidance on insider dealing provides multiple examples:

A dealer on the trading desk of a firm dealing in oil derivatives accepts a very large order from a client to acquire a long position in oil futures deliverable in a particular month. Before executing the order, the dealer trades for the firm and on his personal account by taking a long position in those oil futures, based on the expectation that he will be able to sell them at profit due to the significant price increase that will result from the execution of his client’s order. Both trades could constitute insider dealing.

For example, if a passenger on a train passing a burning factory calls his broker and tells him to sell shares in the factory’s owner, the passenger will be using information which has been made public, since it is information which has been obtained by legitimate means through observation of a public event.

Rules

Rules are specific, detailed, and enforceable regulations set by the authorities. They are legally binding, and failure to comply with them can result in penalties, including fines, sanctions, or loss of license.

Rules offer high certainty and clarity, as they explicitly state what is and is not permitted. In the UK, they are designed to implement the principles in specific, tangible ways.

However, the rigidity of rules means that they might not fully capture the nuances of every situation, and they can sometimes lead to a “box-checking” mentality where the focus is more on formal compliance than on achieving the underlying objectives of the regulation.

In instances when the standard practice is to provide additional guidance alongside rules, the rules can use more abstract phrasing, such as “act with integrity.” We can see this in COCON, where examples of rules are “You must act with due skill, care, and diligence” and “You must pay due regard to the interests of customers and treat them fairly.” However, the terms are more clearly defined with examples in the linked guidance. For example, the following guidance is provided under “Acting with due skill, etc. as a manager”:

It is important for a manager to understand the business for which they are responsible. A manager is unlikely to be an expert in all aspects of a complex financial services business. However, they should understand and inform themselves about the business sufficiently to understand the risks of its trading, credit or other business activities.

Climate Risk Financial Regulation in the UK

Context on UK Financial Regulatory Framework

The Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), and the Bank of England (BoE) are all key institutions in the UK’s financial regulatory framework.

The BoE is the PRA’s parent institution and the UK’s central bank, setting monetary policy and working to maintain the stability and integrity of the UK financial system.

The PRA, a subsidiary of the BoE, is responsible for the prudential regulation and supervision of banks, building societies, credit unions, insurers, and major investment firms.

The FCA, on the other hand, operates independently of the BoE. It is tasked with protecting consumers, maintaining market integrity, and promoting competition in financial services, effectively regulating the conduct of nearly 60,000 financial services firms and financial markets in the UK.

History of Climate Risk Considerations in the UK Financial Industry

The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) was initiated by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) in 2015 under the chairmanship of Mark Carney, who was then the Governor of the Bank of England. TCFD encouraged firms to disclose comprehensive, high-quality information about climate-related risks to promote informed decision-making. The TCFD recommendations are the basis for many climate risk standards that several entities have gradually adopted.

However, the broader history of climate risk considerations in the UK financial industry goes back to at least the early 2000s. The groundwork for these considerations was laid in 2002 when the UK’s Environment Agency, a public body established in 1996 responsible for protecting and improving the environment in England, partnered with FTSE Group, a British provider of stock market indices and associated data services, to create two new indices related to environmental performance. These were the FTSE Environment Technology Index and the FTSE Environment Opportunities Index. These indices also served as early examples of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investment, which has since become a significant trend in the financial industry worldwide.

Further back, in the 1990s, various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) were advocating for greater attention to climate risk in the financial sector, including Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace. These NGOs used a variety of strategies to press for greater attention to climate concerns, including direct action, lobbying, and research.

The UK’s consideration of climate risk has also been informed by international discussions and initiatives, such as the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment launched in 2006.

The TCFD was not a UK-specific initiative but was global in nature. However, it significantly impacted the UK due to Mark Carney’s position and the UK’s position as a global financial hub. The TCFD developed voluntary, consistent climate-related financial risk disclosures for use by companies in providing information to stakeholders. It published its final recommendations in June 2017, which include disclosure guidance across four core elements of how organizations operate: governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics/targets.

In alignment with the TCFD, the UK financial industry has been a pioneer in considering climate risks. In April 2019, building on both their 2015 insurance report and 2018 banking report, the BoE’s PRA became the first central bank and supervisor to set supervisory expectations (Supervisory Statement 3⁄19) for banks and insurers on the management of climate-related financial risks, covering governance, risk management, scenario analysis, and disclosure. The PRA also introduced a biennial climate scenario exercise to assess the resilience of the UK banking system to different climate scenarios.

In March 2023, the BoE published a report on climate-related risks and regulatory capital frameworks. This report sets out the bank’s latest thinking on the extent that climate-related risks might be captured by the regulatory capital frameworks and focus areas identified in the 2021 Climate Adaptation Report to understand the materiality of the gaps.

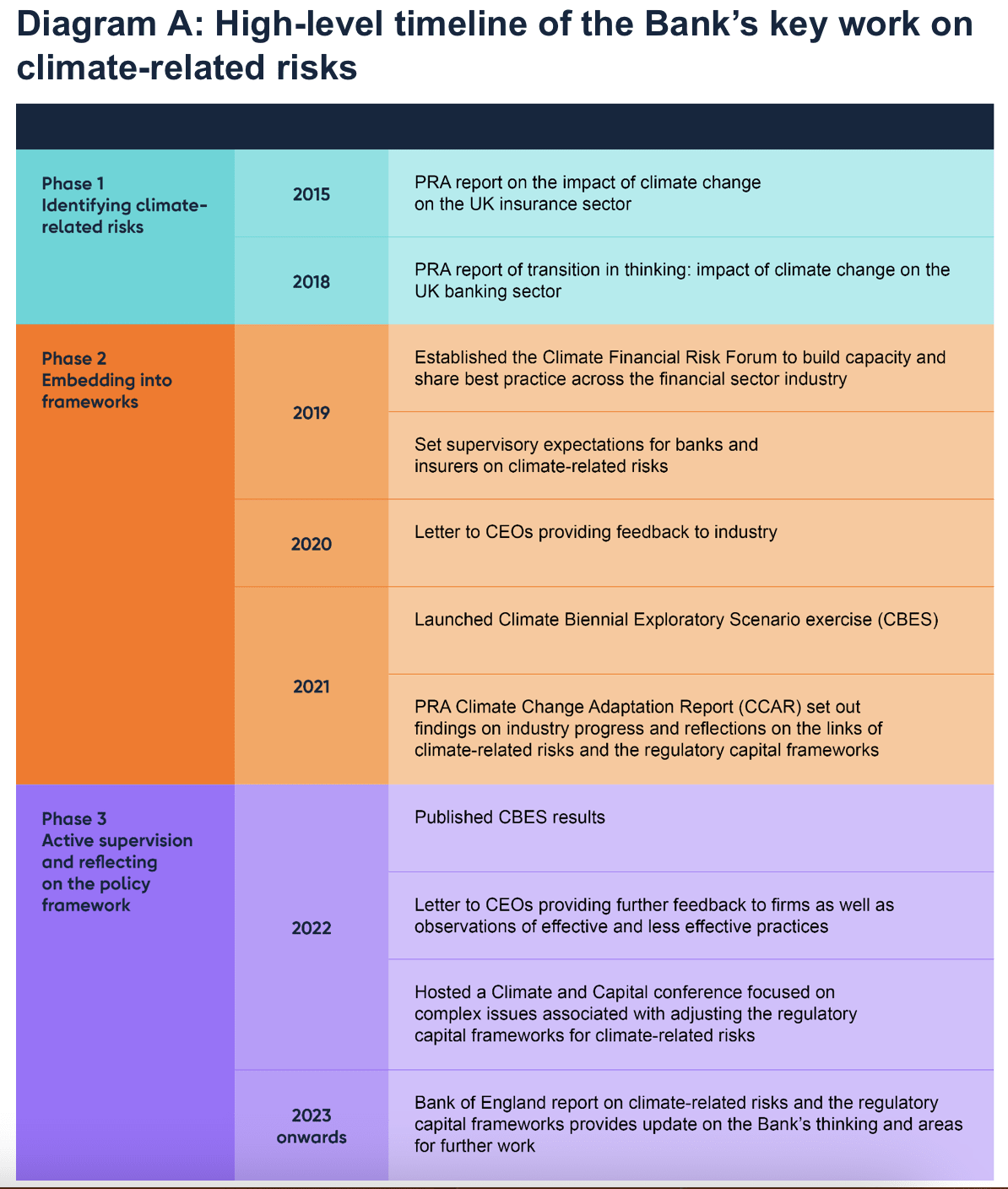

See diagrams in Appendix illustrating the BoE’s approach to Climate Risk.

Assessing Exposure to Climate Risk Involves Complex Risk Assessment

The PRA’s SS3/19 guidance advises firms to comprehensively understand how climate change can impact their business models and strategies. This means using risk management tools, including climate scenario analysis and stress testing, to assess both the short-term and long-term risks and impacts of climate change. The FCA, in turn, has enforced rules for disclosing climate-related risks, enabling transparency and facilitating more informed decision-making.

The BoE’s March 2023 report emphasizes the importance of longer-term thinking when it comes to Climate Risk:

Firms are also already expected to evidence how they would manage risks over longer scenarios than those in the capital frameworks. For example, banks and insurers are already expected to consider longer-term adverse scenarios in their ICAAPs and ORSAs and be able to evidence how they would manage those risks appropriately. Therefore, when climate risks are fully embedded within firms’ risk management frameworks, they should be able to evidence how they would manage those risks over all the relevant horizons.

Implementation of Climate Risk Standards

The PRA’s SS3/19 expects firms to integrate the consideration of climate-related financial risks into their governance frameworks, risk management processes, scenario analysis, and disclosure. Companies that fail to comply with these standards face potential regulatory sanctions.

The key expectations are for firms to:

Embed climate-related financial risks into their governance framework;

Allocate responsibility for identifying and managing climate-related financial risks to the relevant existing Senior Management Function (SMF) and ensure that these responsibilities are included in the SMF’s Statement of Responsibilities;

Incorporate climate-related financial risks into existing risk management frameworks;

Undertake longer-term scenario analysis to inform strategy and risk assessment; and

Develop an appropriate approach to climate disclosure in line with the FSB’s TCFD framework.

In July 2020, the PRA sent a letter to the CEOs of firms stating that: “by the end of 2021, your firm should be able to demonstrate that the expectations set out in SS3/19 have been implemented and embedded throughout your organization as fully as possible”.

Recognizing the challenges firms face, they were also provided with additional guidance on how to meet these expectations, feedback on progress to date across the sector, and sharing examples of good practice.

In a follow-up 2022 letter to CEOs, the PRA issued more guidance. This letter gave the following guidance:

Governance

Boards and Executives should understand and demonstrate the integration of climate considerations into business strategies, planning, governance structures, and risk management processes.

They should show a coherent approach supported by metrics and risk appetites measuring vulnerabilities to climate risk.

Firms should consider the climate in advance of business and strategic decisions.

Risk management

Firms should have climate risk understanding embedded in their Risk Management Framework (RMF), Risk Appetite Statement (RAS), committee structures, and three lines of defense.

RMF should include appropriately factored climate risks in quantitative analysis, with proper climate risk modeling, metrics, and use of assumptions and proxies where data gaps exist.

Firms should have a counterparty engagement strategy to consider climate risks in their business strategy and risk appetite.

Firms’ Own Risk and Solvency Assessments (ORSAs) or Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Processes (ICAAPs) should provide sufficient information on the analysis of climate risks and capital, including disclosure of methodologies, assumptions, judgments, and uncertainties.

Scenario analysis

Firms should demonstrate the integration of scenario analysis into risk management and business planning processes.

Firms should explain how their capabilities develop over time and how selected scenarios test their specific vulnerabilities.

Data

Firms should explain how they identify significant data gaps, plans to close them, and processes to identify and incorporate developments in data and tools.

Firms should have contingency solutions where data gaps exist using appropriately conservative assumptions, judgments, and proxies.

Beginnings as a Voluntary Framework

The TCFD began as a voluntary framework, but due to slow adoption by firms, calls for mandatory climate risk disclosures increased.

As a result, the UK announced in 2020 that it would make TCFD-aligned disclosures fully mandatory across the economy by 2025. This shift from voluntary to compulsory disclosures shows the growing recognition of climate risk as a significant factor in financial stability.

However, voluntary TCFD recommendations were highly influential in shaping later government regulations. The UK’s commitment to mandatory TCFD-aligned disclosures is an example of a voluntary standard shaping regulatory expectations.

From the press release “UK to enshrine mandatory climate disclosures for largest companies in law”

The Taskforce on Climate- Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) is an industry-led group which helps investors understand their financial exposure to climate risk and works with companies to disclose this information in a clear and consistent way. It was launched at the Paris COP21 in 2015 by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and Mark Carney, the UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance and UK Finance Adviser for COP26, and has since published a clear and achievable set of recommendations on climate-related financial disclosures.

Our decision to require mandatory disclosures comes ahead of the G20 and COP26 summits, and it will increase the quantity and quality of climate-related reporting across the UK business community, including among some of the most economically and environmentally significant companies. This will ensure businesses consider the risks and opportunities they face as a result of climate change and encourage them to set out their emission reduction plans and sustainability credentials.

Example of Proactive Regulation

Climate Risk standards aim to be proactive in preventing future climate-related financial risks. By encouraging companies to disclose their climate-related risks and incorporate them into their decision-making processes, the standard aims to mitigate the potential future impacts of these risks on the economy.

According to Sam Woods, CEO of the PRA and Deputy Governor for Prudential Regulation, BoE:

Climate change requires us to take an equally ambitious approach, and a proactive response is needed to ensure financial institutions are resilient to the financial risks from climate change and able to support an economy-wide transition to net-zero emissions. Delivering against this is a priority for the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and the wider BoE

Climate Risk Audits

The BoE ran its first exploratory scenario exercise on climate risk, involving the largest UK banks and insurers, in 2021. The CBES findings can be found in this report.

The CBES includes three scenarios exploring transition and physical risks to different degrees:

Early Action: The transition to a net-zero economy begins in 2021, with a gradual intensification of carbon taxes and other policies. Carbon dioxide emissions will reach net zero by approximately 2050, limiting global warming to 1.8°C relative to pre-industrial levels. While some sectors are more adversely affected than others, the overall impact on GDP growth is limited, especially in the latter half of the transition period, due to productivity benefits from green technology investments.

Late Action: The implementation of policy to facilitate the transition is delayed until 2031, leading to a more sudden and chaotic transition. The condensed time frame for reducing emissions leads to significant short-term macroeconomic disruption, particularly in carbon-intensive sectors, reducing employment and increasing financial risk. Despite the disruption, global warming is still limited to 1.8°C relative to pre-industrial levels by 2050.

No Additional Action: No new climate policies are introduced in this scenario. This lack of action increases greenhouse gas concentrations, leading to a temperature rise of 3.3°C by the end of the scenario relative to pre-industrial levels. The increased temperatures result in changes to precipitation, ecosystems, and sea levels and the frequency and severity of extreme weather events. These changes permanently impact living and working conditions and infrastructure, leading to lower global GDP growth and increased macroeconomic uncertainty. These impacts are expected to worsen in the 21st century, and some effects will become irreversible.

PRA’s 2021 Climate-related financial risk management and the role of capital requirements report includes charts showing the predicted changes in carbon price, emissions and temperature in the three scenarios:

Similarly, the European Central Bank runs supervisory climate risk stress tests in the EU to identify challenges banks face when managing related risks. While this exercise has no direct capital impact on banks, results could indirectly impact Pillar 2 capital requirements through the Supervisory Risk and Evaluation Process.

The Climate Financial Risk Forum (CFRF), an industry forum jointly convened by the PRA and FCA to build capacity and share best practices, published a Climate Scenario Analysis guide in June 2020 which provides more practical guidance on how to use scenario analysis to assess climate-related financial risks. Although the guide is not prescriptive and does not form part of the CBES regulation, it provides useful information for firms looking for best practices when it comes to complying with the existing Climate Risk regulation.

Penalty for Non-compliance

If a company fails to comply with the PRA’s expectations, it risks regulatory sanctions, including fines or public censure. Moreover, firms not adequately managing climate risks may face financial losses due to inadequate risk management frameworks.

Success to Date

According to PRA’s 2021 Climate-related financial risk management and the role of capital requirements report, since initiating the PRA’s climate work in 2015, firms have improved their understanding of climate-related financial risks. They are increasingly investing in managing these risks.

There are, however, varying levels of progress across key areas:

Governance: Significant progress has been made, with Senior Management Functionaries assuming responsibility for managing climate-related risks and boards demonstrating effective oversight.

Risk Management: Firms are improving risk management for climate but are often hampered by a need for granular data. Firms are encouraged to use proxies and expert judgment to manage these risks in the short-to-medium term.

Scenario Analysis: Despite data and modeling challenges, firms are exploring different approaches to scenario analysis to inform strategic decisions.

Disclosure: Many large firms now provide some form of climate-related disclosures in line with the TCFD framework.

The 2022 CBES report notes that (‘the Bank’ here refers to the BoE)

UK banks and insurers are making good progress in some aspects of their climate risk management, and this exercise has spurred on their efforts further. But the Bank’s assessment is that UK banks and insurers still need to do much more to understand and manage their exposure to climate risks. The lack of available data on corporates’ current emissions and future transition plans is a collective issue affecting all participating firms. The Bank will give firm-specific feedback to participants, and will use findings from the CBES to help target their efforts.

One recurrent theme across participants’ submissions was a lack of data on many key factors that participants need to understand to manage climate risks. Another was the range in the quality of different approaches taken across organisations to the assessment and modelling of these risks

The scenario also enabled the BoE to make some concrete predictions about the effects of climate change and shifts to greener energy sources on the financial system:

Banks’ projected climate-related credit losses were 30% higher in the Late Action (LA) scenario than the Early Action (EA) scenario. Loss rates in the LA scenario were projected to more than double as a result of climate risks – equivalent to an extra c.£110 billion of losses for participating banks over the period. Around 40% of these losses were realised during the first five years of transition. Key drivers were the large increase in carbon prices contained in this scenario, which leads to large corporate loan losses across energy users and energy producers, and the economy-wide recession, including a rise in unemployment and fall in house prices caused by the sharp adjustment process, leading to significant mortgage impairments. These household losses were particularly heavily concentrated in the first five years after the delayed start of the transition.

For general insurers, the key way that losses materialised was via a build-up in physical risks, which resulted in higher claims for perils such as flood and wind related damage. UK and international general insurers, respectively, projected a rise in average annualised losses of around 50% and 70% by the end of the NAA scenario. Staff analysis on UK insurance losses suggests increases could be as much as four times higher than firms submitted. Insurers reported that the impact of these increased domestic and international insurance claims would fall, ultimately, on households and businesses through higher insurance premiums or through lower availability of insurance cover.

Appendix: Diagrams

From BoE report on climate-related risks and the regulatory capital frameworks, March 2023

From Climate change page on BoE webpage:

At the start of your post, you said, rather tantalisingly: “I believe that many of the learnings from the creation of climate risk financial regulation in the UK can be applied to AI regulation.” Could you expand on this?

Also, I’m pleased you wrote this post :-)