Strategies for managing jet lag and recommendation for Timeshifter app

Summary

Jet lag is caused by disruption of the circadian rhythm due to abrupt change in the timing of light and dark cycles after travelling across timezones. Jet lag symptoms can be managed by seeking or avoiding light at certain times before travel and during transit, using caffeine and melatonin, and shifting sleep and eating patterns to align with the destination timezone.

If you regularly travel internationally across timezones, I recommend a paid app called Timeshifter that creates personalised plans based on travel information (e.g., flight details) for adjusting your circadian system. Based on testimonials from other Australians, I estimate an average benefit of about 1.2 good days (range: 1 to 5) per trip from avoided / well-managed jet lag.

Jet lag is caused by an abrupt change in day/night cycle

Effective Altruism is a highly internationalised community. People work remotely across timezones, and can travel long distances to attend conferences or for work. Travelling across timezones can lead to jet lag, where our circadian rhythms are disrupted by a sudden change in day and night cycles.

The circadian rhythms are a collection of ~24-hour cyclic processes that manage many bodily functions, including wakefulness and sleep (Vosko et al 2010; Waterhouse et al 2007). A part of the hypothalamus called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) acts as a master regulator of these rhythms. The rhythm of the SCN itself is maintained by photosensitive cells in your eyes, which get more light during daytime hours and less light during nighttime hours.

The SCN regulates the circadian rhythms in several ways, such as through direct neural influence, central nervous system influence, and hormonal influence, such as signalling the pineal gland to produce melatonin in the absence of light, or suppress melatonin in the presence of light.

When you shift timezones, the pattern of daylight and nighttime abruptly changes; the SCN now receives signals from the retina that are very different from its existing rhythm. As a result, the circadian system is disrupted, leading the individual rhythms to desynchronise from each other and the SCN master regulator. Over several days, the rhythms readjust based on the new pattern of light and dark from the destination timezone.

In the meantime, you may experience symptoms like waking up and going to sleep at the wrong time, being alert / active and being drowsy / lethargic at the wrong time, sleeping for the wrong length of time (e.g., only 3-4 hours even though you usually sleep through the night), changes in appetite and digestion, and mood. This is jet lag!

Jet lag can be effectively managed by seeking and avoiding light at specific times

Systematic reviews for interventions to manage jet lag have found mostly poor quality evidence (Herxheimer & Petrie 2002; Janse van Rensburg et al 2020).

The most effective interventions rely on seeking or avoiding bright light during the period before and after cross-timezone travel, accelerating the natural adaptation of the suprachiasmatic nucleus.

Other interventions with some positive evidence include using melatonin, using caffeine, shifting sleep schedules, or shifting food times. Each of these interventions is based around accelerating adaptation to the destination timezone. This means that they might be in tension with other needs and goals relevant to your lifestyle or travel (e.g., do you need caffeine to stay awake for a presentation on the first day at your destination? Are you willing to go to bed at 8pm on the last night of your trip?)

Seeking and avoiding bright light

The primary method of managing jet lag is to seek and avoid bright light at times consistent with daytime and nighttime at the destination timezone.

The specific pattern of seeking and avoiding light depends on your home timezone and a destination timezone.

In general:

If your destination timezone is later / ahead / eastward than your home timezone, you should seek light early in the morning and avoid light late in the afternoon and evening.

If your destination timezone is earlier / behind / westward than your home timezone, you should avoid light early in the morning and seek light late in the afternoon and evening.

It’s important to recognise that online information often refers to ‘eastward’ and ‘westward’ travel and uses terms like ‘earlier’ or ‘later’; this is easiest to understand in the United States and Europe, but becomes complicated for very long haul travel or travel that crosses the International Date Line (e.g., Australia to UK; China to the US).

Using melatonin

Melatonin can be useful to further accelerate adaptation if synchronised with desired regular sleep times at the destination timezone; a systematic review found no difference in efficacy between 0.5mg and 5mg dose (Herxheimer & Petrie 2002).

Using caffeine

Caffeine may be useful to help stay awake for other adaptation activities (e.g., seeking/avoiding light, sleep schedule), but can reduce sleep quality and make adaptation worse.

Shifting sleep schedule

Napping during transit can be helpful for staying awake until bedtime at the destination timezone, so long as this doesn’t interfere with seeking / avoiding light.

Trying to sleep and wake at times consistent with the destination timezone (e.g., while in transit) can be helpful for adaptation, and can also help to reduce the fatigue of travel.

Shifting food times

Changing your meal times to align with the destination time may be helpful for improving lifestyle and digestive adaptation to the destination.

Caveats

The relevance and usefulness of these interventions depends on when you are travelling (e.g., during the day or night), how you are travelling (e.g., stopovers or flight changes), opportunities, needs and responsibilities before and after travel (e.g., work and caring responsibilities, social events), and other factors.

It’s also worth noting that jet lag and travel fatigue are separate issues that are experienced concurrently. So even if you reduce the disruption of circadian rhythms from jet lag, you may still have flown 8+ hours in a cramped seat and feel exhausted!

Example management plan for jet lag: London to New York City

In this management plan, the traveller is flying from a home timezone of London UTC+0, to a destination timezone of New York City UTC-5. This is so-called ‘westward’ travel, where NYC is earlier than / behind London.

| Timezones | Home (London): UTC+0 Destination (New York City): UTC-5 9am in London is 4am in New York City |

| Common terms of comparison | New York City is earlier than London New York City is behind London New York City is ‘westward’ from London |

| Example flight | Virgin Atlantic VS45 13:20 LHR − 16:25 JFK (8 hour flight) |

| Jet lag management plan | Avoid bright light in the morning (e.g., wear sunglasses everywhere) and seek bright light in the evening before you leave London. This will delay your internal clock so that you are awake later and sleepy later. Also consider:

Avoid bright light in the morning and seek bright light in the evening for the first few days after arriving in New York City. Depending on the details of the return flight, execute the opposite strategy for seeking / avoiding light when returning to London. |

Timeshifter: A paid app to create personalised management plans for jet lag

Timeshifter is an app that creates personalised plans for managing jet lag. After the first free trip, it requires an annual subscription of $25 USD for unlimited additional trips. The key value proposition of the app is that it figures out what you need to do to manage jet lag for a specific trip (i.e., it automates the management plan).

Timeshifter advertises itself as using ‘the science of jet lag’ to make recommendations about seeking / avoiding light, sleeping, using caffeine and/or melatonin, pre-adaptation, etc. Based on my brief research (see references at end of article), its recommendations are consistent with the best public scientific evidence for managing jet lag.

Creating a management plan in Timeshifter

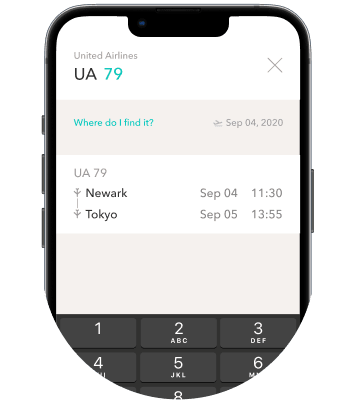

Creating a plan in Timeshifter involves entering the flight details for your trip and giving personal preferences (e.g., whether you wish to use caffeine, your chronotype).

Once your flight details have been entered (multiple segments of a journey are supported, e.g., MEL—AUH—LHR), the app creates a jet lag management plan with directions about when to seek / avoid light, use / avoid caffeine and melatonin, and nap or sleep.

Effectiveness of Timeshifter for managing jet lag

Several people in the Australian EA community have used Timeshifter for international travel. Here is what they said when I asked how many more good days they got during international travel when using Timeshifter vs. not using Timeshifter:

“About 5 days per year are about 50% better than they otherwise would have been, at a time where those days are 2-10x more important than typical days of the year”

“About 1-2 days per international trip”

“I’ve used it once from Aus to UK and back, and I’d say it gave me a net benefit of a full productive day”

“I get about 3 days per trip at 70% of normal instead of 30% of normal”

I estimate that this is a range of about 1 to 5 ‘good days’ per trip, with a median of about 1.2 days per trip.

The bottom line

If you travel long distances internationally, you should consider using Timeshifter to get an average benefit of about 1.2 days of avoided / well-managed jet lag.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Grace Adams, who must be recognised as the first and rightful discoverer of Timeshifter, and who generously shared it with Australian EAs including me. Thanks also to several Australian EAs for sharing their experience with jet lag and Timeshifter. I declare no conflicts of interest in writing this article.

References

Herxheimer, A., & Petrie, K. J. (2002). Melatonin for the prevention and treatment of jet lag. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), CD001520. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001520 [open access]

Janse van Rensburg, D. C., Jansen van Rensburg, A., Fowler, P., & et al. (2020). How to manage travel fatigue and jet lag in athletes? A systematic review of interventions. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54, 960-968. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101635 [open access]

Vosko, A. M., Colwell, C. S., & Avidan, A. Y. (2010). Jet lag syndrome: Circadian organization, pathophysiology, and management strategies. Nature and Science of Sleep, 2, 187-198. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S6683 [open access]

Waterhouse, J., Reilly, T., Atkinson, G., & Edwards, B. (2007). Jet lag: Trends and coping strategies. The Lancet, 369(9567), 1117-1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60529-7 [subscription required]

I really like time shifter but honestly the following has worked better for me:

Fast for ~16 hours prior to 7am in my new time-zone.

Take melatonin, usually ~10pm in my new timezone and again if I wake up and stop feeling sleepy before around 5am in my new timezone. (I have no idea if this second dosing is optimal but it seems to work).

I highly recommend getting a good neck pillow, earplugs, and eye mask if you travel often or on long trips (e.g. if you are Australian and go overseas almost anywhere).

Thanks to Chris Watkins for suggesting the fasting routine.

Glad that fasting works for you! I have tried it a couple of times and have found myself too hungry or uncomfortable to sleep at the times I need to (eg, a nap in the middle of the flight).

Great points on equipment; I think they are necessary and think that the bulk of a good neck pillow in carry on luggage is justified because I can’t sleep without it. I also have some comically ugly and oversized sunglasses that fit over my regular glasses and block light from all sides.