I’m currently researching forecasting and epistemics as part of the Quantified Uncertainty Research Institute.

Ozzie Gooen

Sure thing!

1. I plan to update it with new model releases. Some of this should be pretty easy—I plan to keep Sonnet up to date, and will keep an eye on other new models.

2. I plan to at least maintain it. This year I can expect to spend maybe 1/3rd the year on it or so. I’m looking forward to seeing what use and the response is like, and will gauge things accordingly. I think it can be pretty useful as a tool, even without a full-time-equivalent improving it. (That said, if anyone wants to help fund us, that would make this much easier!)

3. I’ve definitely thought about this, can prioritize. There’s a very high ceiling for how good background research can be for either a post, or for all claims/ideas in a post (much harder!). Simple version can be straightforward, though wouldn’t be much better than just asking Claude to do a straightforward search.

I’m looking now at the Fact Check. It did verify most of the claims it investigated on your post as correct, but not all (almost no posts get all, especially as the error rate is significant).

It seems like with chickens/shrimp it got a bit confused by numbers killed vs. numbers alive at any one time or something.

In the case of ICAWs, it looked like it did a short search via Perplexity, and didn’t find anything interesting. The official sources claim they don’t use aggressive tactics, but a smart agent would have realized it needed to search more. I think to get this one right would have involved a few more searches—meaning increased costs. There’s definitely some tinkering/improvements to do here.

Thanks! I wouldn’t take its takes too seriously, as it has limited context and seems to make a bunch of mistakes. It’s more a thing to use to help flag potential issues (at this stage), knowing there’s a false positive rate.

Thanks for the feedback!

I did a quick look at this. I largely agree there were some incorrect checks.

It seems like these specific issues were mostly from the Fallacy Check? That one is definitely too aggressive (in addition to having limited context), I’ll work on tuning it down. Note that you can choose which evaluators to run on each post, so going forward you might want to just skip that one at this point.

Sounds good, thanks! When you get a chance to try it, let me know if you have any feedback!

I can also vouch for this. I think that the bay area climate is pretty great. Personally I dislike weather above 80 degrees F, so the Bay is roughly in my ideal range.

I’ve lived in SF and Berkeley and haven’t found either to be particularly cloudy. I think that it really matters where you are in SF.

“Should EA develop any framework for responding to acute crises where traditional cost-effectiveness analysis isn’t possible? Or is our position that if we can’t measure it with near-certainty, we won’t fund it—even during famines?”

This is tricky. I think that most[1] of EA is outside of global health/welfare, and much of this is incredibly speculative. AI safety is pretty wild, and even animal welfare work can be more speculative.

GiveWell has historically represented much of the EA-aligned global welfare work. They’ve also seemed to cater to particularly risk-averse donors, from what I can tell.So an intervention like this is in a tricky middle-ground, where it’s much less speculative than AI risk, but more speculative than much of the GiveWell spend. This is about the point where you can’t really think of “EA” as one unified thing with one utility function. The funding works much more as a bunch of different buckets with fairly different criteria.

Bigger-picture, EAs have a very small sliver of philanthropic spending, which itself is a small sliver of global spending. In my preferred world we wouldn’t need to be so incredibly ruthless with charity choices, because there would just be much more available.

[1] In terms of respected EA discussions/researchers.

“Though I think AI is critically important, it is not something I get a real kick out of thinking and hearing about.”

-> Personally, I find a whole lot of non-technical AI content to be highly repetitive. It seems like a lot of the same questions are being discussed again and again with fairly little progress.

For 80k, I think I’d really encourage the team to focus a lot on figuring out new subtopics that are interesting and important. I’m sure there are many great stories out there, but I think it’s very easy to get trapped into talking about the routine updates or controversies of the week, with little big-picture understanding.

Thanks for writing this, and many kudos for your work with USAID. The situation now seems heartbreaking.

I don’t represent the major funders. I’d hope that the ones targeting global health would be monitoring situations like these and figuring out if there might be useful and high-efficiency interventions.Sadly there are many critical problems in the world and there are still many people dying from cheap-to-prevent malaria and similar, so the bar is quite high for these specific pots of funding, but it should definitely be considered.

This feels highly targeted :)

Noted, though! I find it quite difficult to make good technical progress, manage the nonprofit basics, and do marketing/outreach, with a tiny team. (Mainly just me right now). But would like to improve.

We’ve recently updated the models for SquiggleAI, adding Sonnet 4.5, Haiku 4.5, and Grok Code Fast 1.

Initial tests show promising results, though probably not game-changing. Will run further tests on numeric differences.

People are welcome to use (for free!) It’s a big unreliable, so feel free to run a few times on each input.https://quantifieduncertainty.org/posts/updated-llm-models-for-squiggleai/

Quickly → I sympathize with these arguments, but I see the above podcast as practically a different topic. Could be a good separate blog post on its own.

This got me to investigate Ed Lee a bit. Seems like a sort of weird situation.

The corresponding website in question’s about page doesn’t mention him.

Seems like he has another very similar site, https://bitcoiniseatingtheworld.com/, for reference, also with no about section

Here seems to be his Twitter page, where he advertises his new NFT book.

Good point about it coming from a source. But looking at that, I think that that blog post was had a similarly clickbait headline, though more detailed (“Anthropic faces potential business-ending liability in statutory damages after Judge Alsup certifies class action by Bartz”).

The analysis in question also looks very rough to me. Like a quick sketch / blog post.

I’d guess that if you’d have most readers here estimate what the chances seem that this will actually force the company to close down or similar, after some investigation, it would be fairly minimal.

The article broadly seems informative, but I really don’t like the clickbait headline.

“Potentially Business-Ending”?

I did a quick look at the Manifold predictions. In this (small) market, there’s a 22% chance given to “Will Anthropic be ordered to pay $1B+ in damages in Bartz v. Anthropic?” (note that even $1B would be far from “business-ending”).

And larger forecasts of the overall success of Anthropic have barely changed.

I’d be curious to hear what you think about telling the AI: “Don’t just do this task, but optimize broadly on my behalf.” When does that start to cross into dangerous ground?

I think we’re seeing a lot of empirical data about that with AI+code. Now a lot of the human part is in oversight. It’s not too hard to say, “Recommend 5 things to improve. Order them. Do them”—with very little human input.

There’s work to make sure that the AI scope is bounded, and that anything potentially-dangerous it could do gets passed by the human. This seems like a good workflow to me.

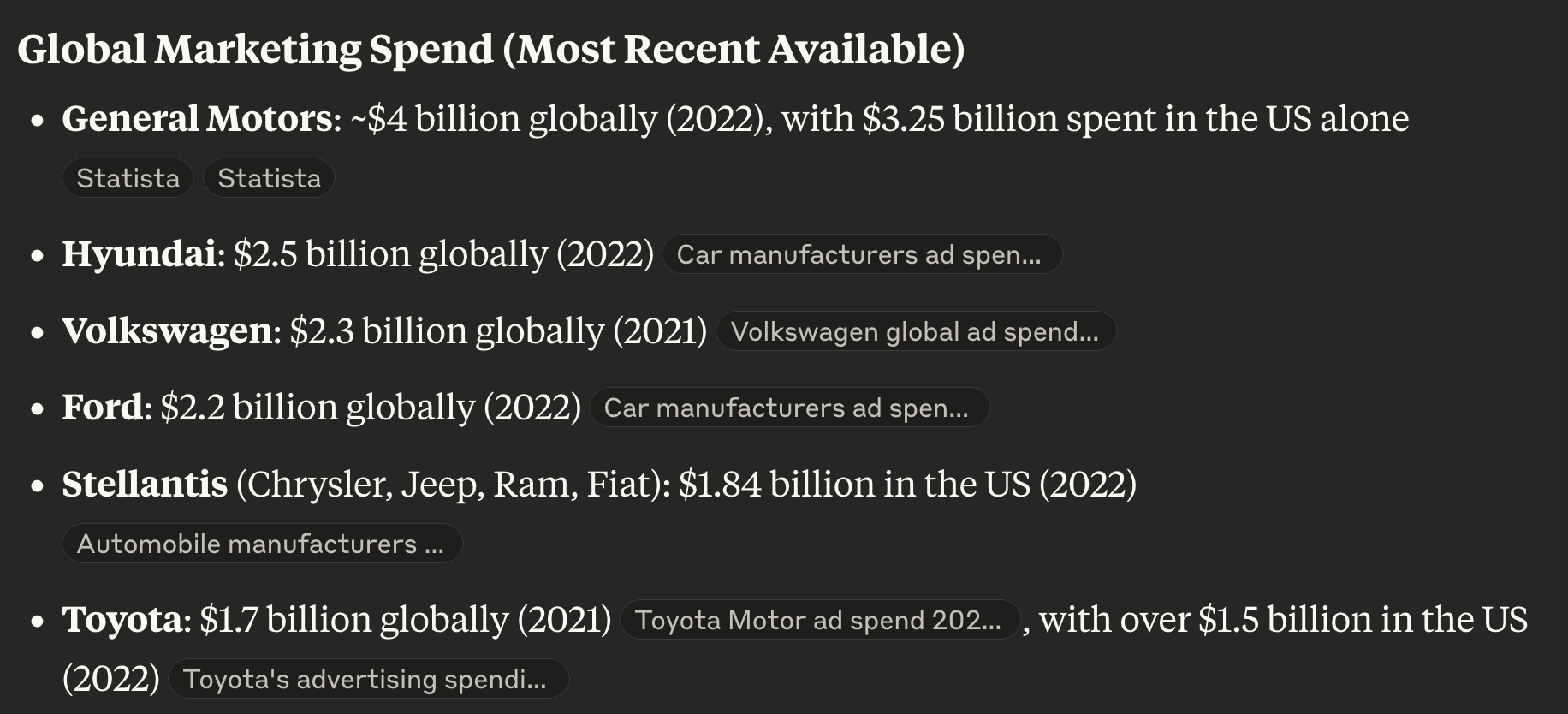

Frustratingly, the links that Claude found for these went to Statista, which is mostly paywalled, but the public bits mostly seem to verify these rough numbers.

https://claude.ai/share/941fbda6-2dc5-4d15-bb31-99fcfc4d0a8b

To give more clarity on what I mean by imagining larger spends—it seems to me like many of these efforts are sales-heavy, instead of being marketing-heavy.

I can understand that it would take a while to scale up sales. But scaling up marketing seems much better understood. Large companies routinely spend billions per year on marketing.

Here are some figures a quick Claude search gave for car marketing spending, for instance. I think this might be an interesting comparison because cars, like charitable donations, are large expenses that might take time for people to consider.

(I do realize that the economics might be pretty different around charity, so of course I’d recommend being very clever and thoughtful before scaling up quite to this level)

How do you imagine the benefits might continue past 2 years?

If any of these can be high-growth ventures, then early work is mainly useful in helping to set up later work. There’s often a lot of experimentation, product-market-fit finding, learning about which talent is good at this, early on.

Related, I’d expect that some of this work would take a long time to provide concrete returns. My model is that it can take several years to convince certain wealthy people to give up money. Many will make their donations late in life. (Though I realize that discounting factors might make the later stuff much less valuable than otherwise)

I made this simple high-level diagram of critical longtermist “root factors”, “ultimate scenarios”, and “ultimate outcomes”, focusing on the impact of AI during the TAI transition.

This involved some adjustments to standard longtermist language.

“Accident Risk” → “AI Takeover

”Misuse Risk” → “Human-Caused Catastrophe”

“Systemic Risk” → This is spit up into a few modules, focusing on “Long-term Lock-in”, which I assume is the main threat.

You can read interact with it here, where there are (AI-generated) descriptions and pages for things.

Curious to get any feedback!

I’d love it if there could eventually be one or a few well-accepted and high-quality assortments like this. Right now some of the common longtermist concepts seem fairly unorganized and messy to me.

---

Reservations:

This is an early draft. There’s definitely parts I find inelegant. I’ve played with the final nodes instead being things like, “Pre-transition Catastrophe Risk” and “Post-Transition Expected Value”, for instance. I didn’t include a node for “Pre-transition value”; I think this can be added on, but would involve some complexity that didn’t seem worth it at this stage. The lines between nodes were mostly generated by Claude and could use more work.

This also heavily caters to the preferences and biases of the longtermist community, specifically some of the AI safety crowd.