Kaya Guides Pilot Results

Summary

Who We Are: Kaya Guides runs a self-help course on WhatsApp to reduce depression at scale in low and middle-income countries. We help young adults with moderate to severe depression. Kaya currently operates in India. We are the world’s first nonprofit implementer of Step-by-Step, the World Health Organization’s digital guided self-help program, which was proven effective in two RCTs.

Pilot: We ran a pilot with 103 participants in India to assess the feasibility of implementing our program on WhatsApp with our target demographic and to generate early indicators of its effectiveness.

Results: 72% of program completers experienced depression reduction of 50% or greater. 36% were depression-free. 92% moved down at least a classification in severity (i.e. they shifted from severe to moderately severe, moderately severe to moderate, etc). The average reduction in score was 10 points on the 27-point PHQ-9 depression questionnaire. Given the lack of a control group, we can’t ascribe all the impact to our program. A percentage of completers would have gotten better with or without our involvement. In the original WHO program, 13.3% of people in the control group experienced reductions of 50% or greater, and 3.9% were depression-free.

Comparison: In the original version of Step-by-Step, 40.1% of program completers responded to treatment (compared to 72% for our pilot) and 21.1% remitted (compared to 36% for our pilot).

Estimated Effect Size: Our effect size is estimated at a moderate effect of 0.54. This is likely to be an upper bound.

Cost-Effectiveness: We estimate that the pilot was 7x as cost-effective as direct cash transfers at increasing subjective well being. This accounts for the initial effect, not duration of effects. The cost per participant was $96.27. We project that next year we will be 20x as cost-effective as direct cash transfers. These numbers don’t reflect our full impact, as we may be saving lives. Four participants said overtly that the program reduced their suicidal thinking.

Impacts: Participants reported that the program had profound impacts on their lives, ranging from improved well-being to regaining control over their lives and advancing in their education and careers.

Recruitment: We were highly successful at recruiting our target population. 97% of people who completed the baseline depression questionnaire scored as having depression. 82% scored moderate to severe. Many of our participants came from lower-income backgrounds even though we did not explicitly seek out this group. Participants held professions such as domestic worker, construction and factory worker and small shopkeeper. 17% overtly brought up financial issues during their guide calls.

Retention: 27% of participants completed all the program content, compared to 32% in the WHO’s most recent RCT. In the context of a digitally-delivered mental health intervention, which are notorious for having extremely low engagement, this is a strong result. Guide call retention was higher: 36% of participants attended at least four guide calls.

Participant Feedback: 96% of program completers said they were likely or very likely to recommend the program. Participant feedback on weekly guide calls was overwhelmingly positive and their commentary gave the sense that guide calls directly drive participant engagement. Negative feedback focused on wanting more interaction with guides. Feedback on the videos was mixed. For the chatbot, it was neutral. Feedback on the exercises was generally positive for the exercises, although there were signs of lack of engagement with some exercises. The stress reduction exercises were heavily favored.

Part 1. About the Kaya Guides Program

What is Kaya Guides and what do we do?

Kaya Guides runs a self-help course on WhatsApp to reduce depression at scale in low and middle-income countries. We focus on young adults with moderate to severe depression and have launched our program in India. We are a global mental health charity incubated by Ambitious Impact/Charity Entrepreneurship.

How the program works

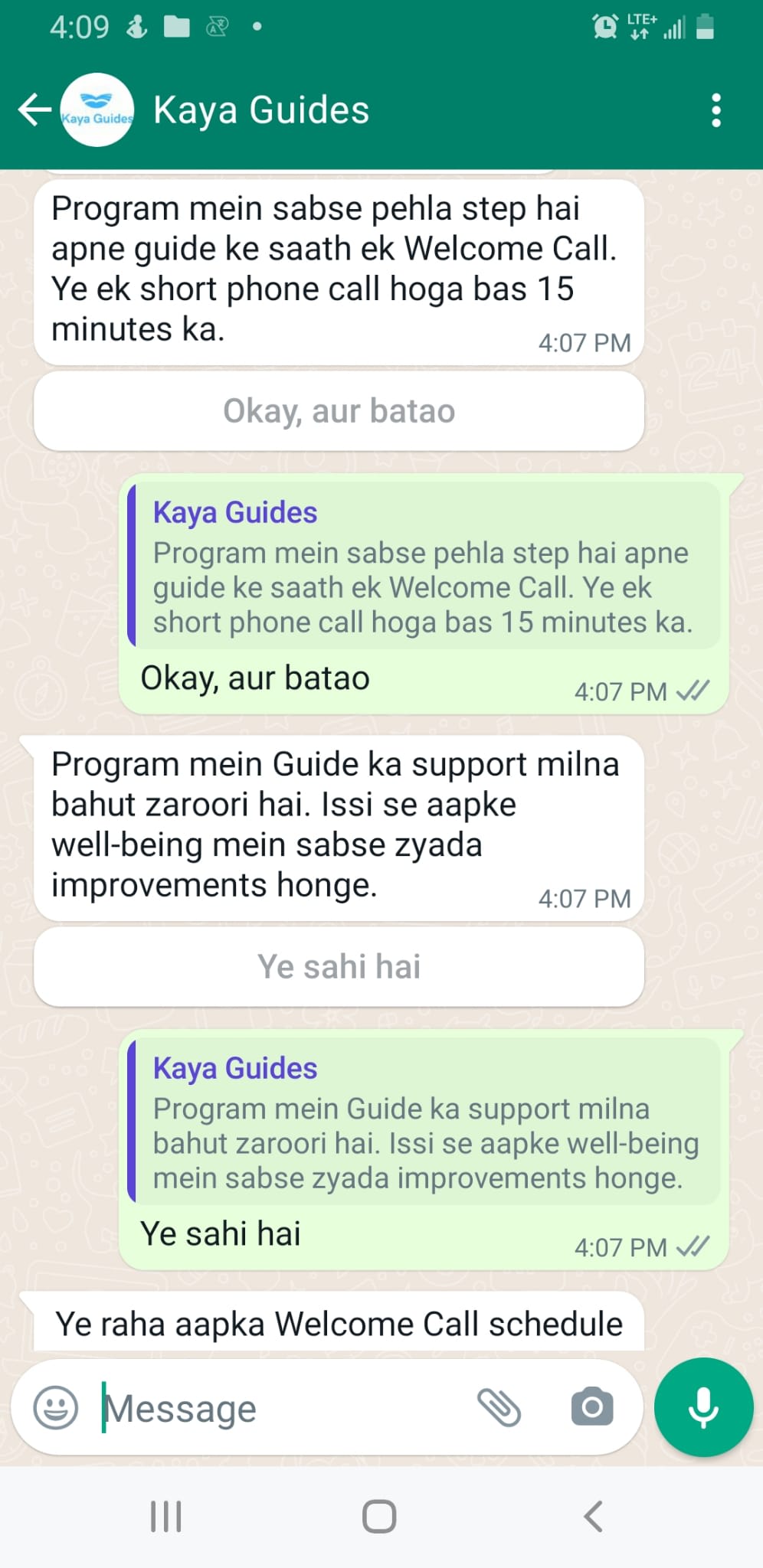

Participants learn evidence-based techniques to reduce depression through a WhatsApp chatbot which sends them videos in Hindi. Once a week, they have a 15-minute call with a trained guide. The program is self-paced and lasts for 5-8 weeks.

.

Evidence base

Overall model: Self-help combined with light-touch human support can be as effective as face-to-face psychotherapy in reducing depression. This holds true even if weekly contacts are only 15 minutes per week and the guide has no clinical background.

Kaya’s program: We adapted the World Health Organization’s digital guided self-help program Step-by-Step, which was found in two RCTs to have moderate to large effects on reducing depression. We are the first nonprofit in the world to implement the WHO’s program.

Why guided self-help is effective

The real therapy takes place on the participant’s own time, by teaching themselves the techniques and then trying them in their life. The primary purpose of a guide is to increase engagement with these techniques: adding low-touch human support keeps participants engaged for a longer period of time. However, participants who speak with a person also experience greater depression reductions than participants who learn and practice the techniques on their own. There is no direct explanation for this phenomenon, but experts speculate it has to do with having someone to talk to and feeling supported.

Why this work matters

There are very few known interventions for improving mental health, even though mental health disorders account for 5% of global disease burden and 15% of all years lived with disability. Therapy and psychiatric treatment represent the majority. Given that therapy tends to be expensive and medication for depression is hit or miss, cost-effective interventions need to be implemented more widely. Guided self-help is underutilized in the real world despite its efficacy and high potential to reach many people for a low cost. If we can scale this program successfully, this could become one of the world’s most cost-effective mental health interventions. As the first implementers of Step-by-Step besides the WHO’s original partner, we have an opportunity to validate their program outside of a research context and directly contribute to their mission of scaling the effective use of Step-by-Step globally. Kaya Guides has the opportunity to massively expand the impact we can have independently.

Program design

Each aspect of our program was designed to maximize impact to the greatest extent possible.

We adapted an existing program rather than creating our own to maximize the chances that our program will work.

We implement on WhatsApp so we can reach individuals from lower-income backgrounds who are less likely to be able to afford therapy.

We focus on individuals with moderate to severe depression because this is where the greatest disease burden lies.

We work with youth because early intervention can reduce depression throughout a person’s lifespan and young people are less likely to seek or get help than older people.

We launched our program in India because the treatment gap is the largest in the world and a large portion of the population has access to smartphones and inexpensive internet.

Target participant profile

Moderate to severe depression

Young adult (18-29 years old)

Lower-income background

Individuals with mild or no depression can participate in the program too, but they go through the content independently, without guide calls. This is to concentrate resources where they’re most needed while maximizing our impact at minimal additional cost to us.

Impact measurement

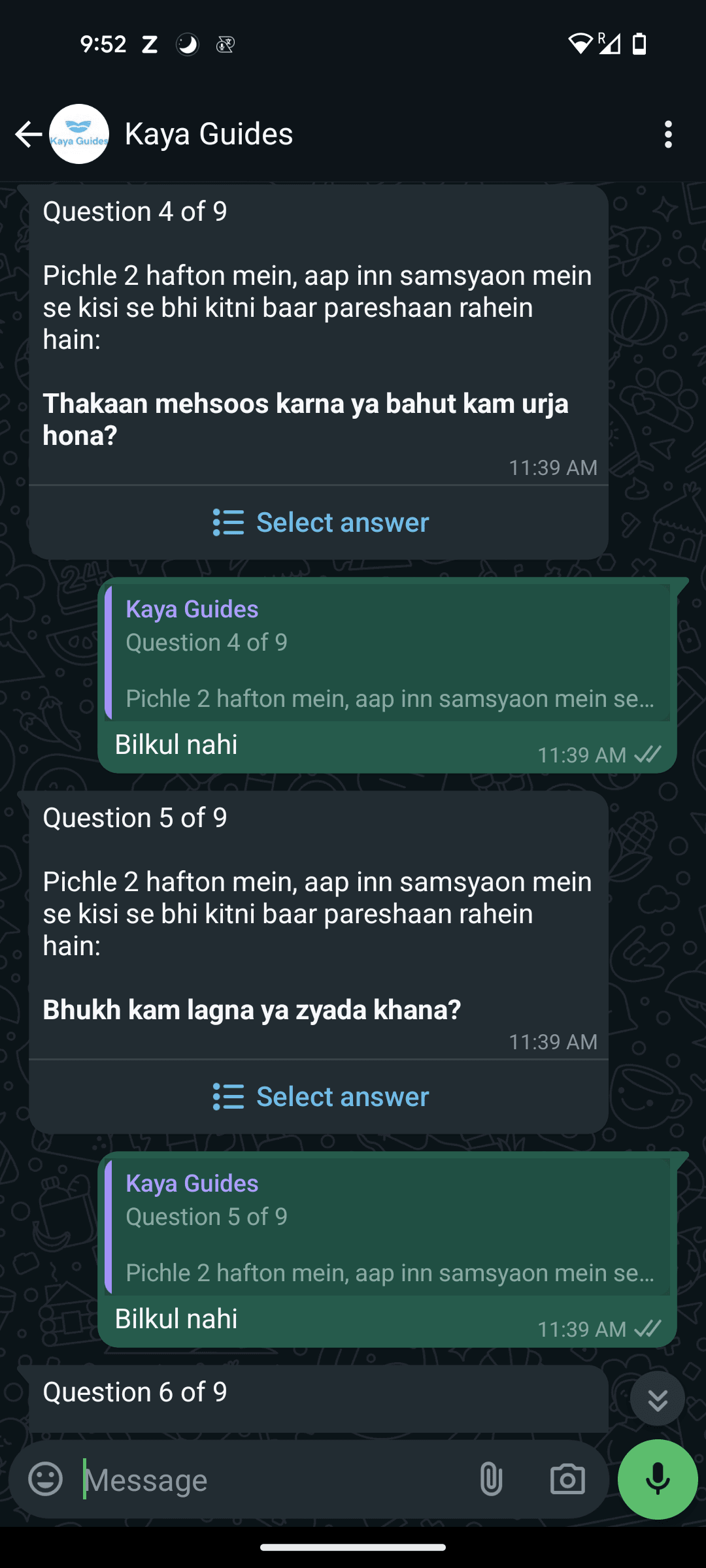

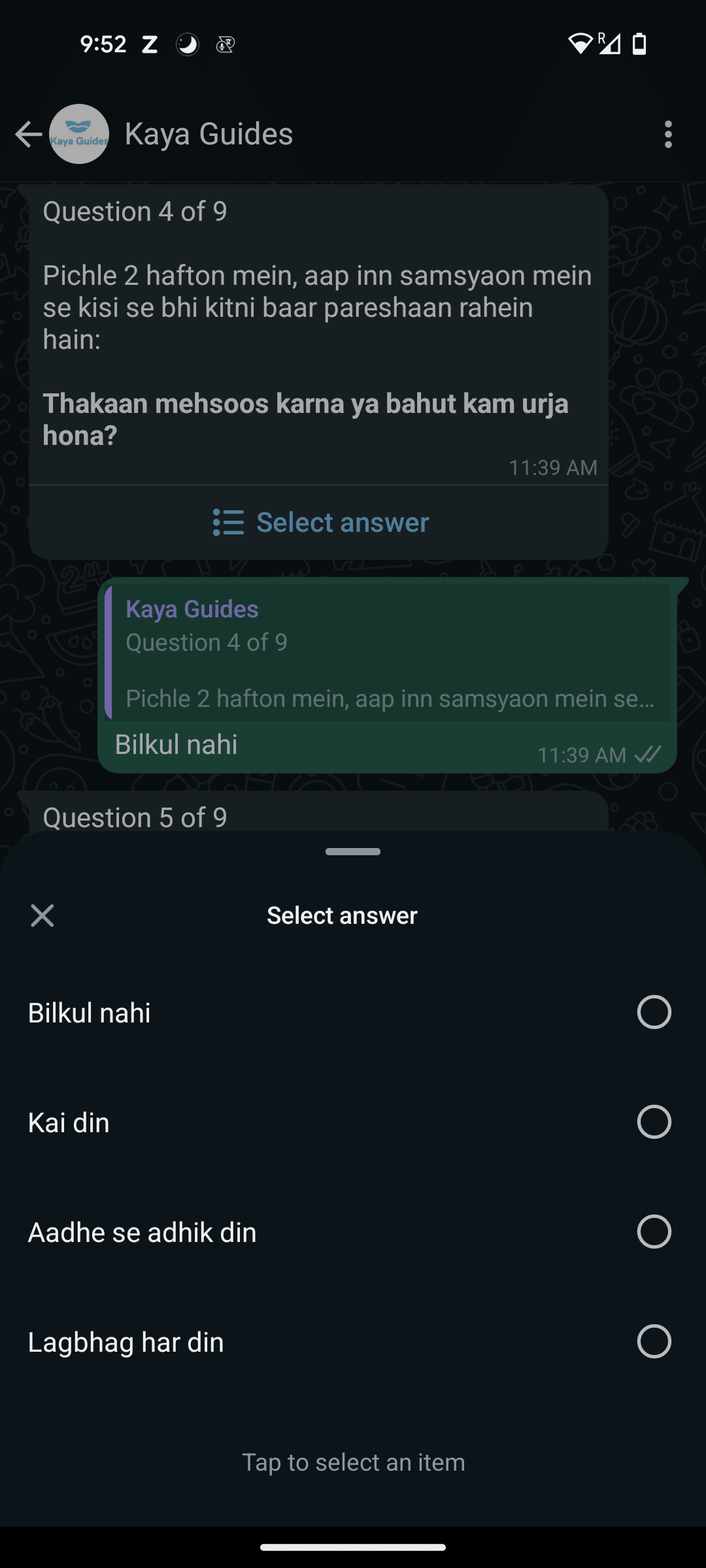

We do simple pre and post measurements of depression severity. Participants complete a nine-question screening questionnaire called the PHQ-9 which scores depression on a 27-point scale. We measure our impact based on:

Treatment Response: 50% or greater reduction in PHQ-9 score

Full Remission: Depression-free, with a score of less than 5 on the PHQ-9

Participants complete the PHQ-9 directly in their WhatsApp chat upon messaging the number, and again upon completing the program. The chatbot automatically calculates their score.

Part 2. Pilot Impact and Cost-Effectiveness

Kaya Guides piloted the program with 103 participants in India to assess the feasibility of implementing on WhatsApp with our target demographic and to generate early indicators of its effectiveness.

Impacts on depression

We are thrilled to report that our program saw significant positive results on decreasing depression. Of the participants who completed all of the program content and the endline PHQ-9:

72% experienced depression reduction of 50% or greater

36% were depression-free

92% moved down at least a classification in PHQ-9 severity (i.e. they shifted from severe to moderately severe, moderately severe to moderate, etc).

The average depression reduction on the 27-point PHQ-9 scale was 10 points.

Effect Size Estimate

These are fantastic results- to the point that they seemed too good to be true. We requested an external review of our data. Joel McGuire, a researcher at the Happier Lives Institute, performed an analysis to determine the causal effect of the pilot. He estimated that our results would translate to moderate impacts on depression, at an effect size of 0.54 standardized mean differences. The WHO’s effect size was 0.48 standardized mean differences, but for all participants regardless of how far they reached in the program. It makes sense our effect size would be higher given that it represents only the outcomes of program completers.

This means, in short, that our results are likely realistic and in line with what we would expect. Joel emphasized that this was only a naive guess based on general evidence about psychotherapy, and believed that our results were probably an upper bound. However, he felt that the results were plausible and consistent with RCTs’ pre-post changes and natural improvement observed in the control groups. He noted that if true, this would be a very respectable effect size.

There are some reasons to be skeptical:

This is a small sample size: 25 participants completed the endline PHQ-9.

We did not set a firm deadline for the pilot. Due to this, as well as mid-pilot delays due to technical difficulties with the chatbot, the pilot duration was longer than its intended length its length moving forward. A few participants participated in the program for as long as 4-5 months. It’s possible that participating for a longer period of time could increase depression impacts (although experts don’t know if this is true).

Given the lack of a control group, we can’t ascribe all the impact to our program. A percentage of our participants would have gotten better with or without our involvement. This is captured in the effect size Joel McGuire has estimated, but to give a more concrete sense of what this would look like: for the original WHO program, 13.3% of people in the control group experienced reductions of 50% or greater*, and 3.9% were depression-free.

*In their study, the control group wasn’t a pure control; they received basic psychoeducation and referral to evidence-based care. This may mean that fewer people would have gotten better had it been a pure control group.

Takeaway

Overall, these are promising initial results. The pilot outcomes suggest that this program can be implemented successfully on WhatsApp and may indicate that our adaptation of Step-by-Step has been effective, although much more data is required to confirm this. We do not expect to achieve this level of depression impact again, and set lower internal goals, but are optimistic that the program will continue to have significant impacts on depression as it’s scaled.

Cost-Effectiveness

We assess our comparative impact in terms of improvement in subjective well-being. To do this, we use cash benchmarking: we compare the subjective well-being improvements of our program with those of directly giving cash to a person living in poverty. Our estimates are based on the estimated effect size for Kaya’s pilot and the Happier Lives Institute’s cost-effectiveness analysis of GiveDirectly.

Pilot Cost-Effectiveness

Costs

We estimate that our pilot was 7x as cost-effective as direct cash transfers at increasing subjective well-being. This figure represents the degree of mental health improvement per $1K spent. Find the basic calculation linked here and pictured below. We use program completers, rather than halfway completers*, to be conservative.

Here’s our cost breakdown**. These figures represent the full cost of running the organization; they are not limited to direct implementation costs. To compare, the Happier Lives Institute’s report indicates that it costs GiveDirectly $1,185 in total to give someone $1K.

Cost Per Participant (Regardless of how far they got in the program content): $96.27

Cost Per Halfway Completer: $260.94

Cost Per Program Completer: $367.25

*We hypothesize that halfway is the point at which participants can begin to experience depression reduction, given that at this point in the program they have learned and practiced the highest-impact exercises. However, the WHO did not administer a midline PHQ-9, so we can’t be certain until we collect more data.

*The pilot duration was longer than the program will be moving forward, so to arrive at our cost-effectiveness estimate, we have used two months of organization-wide expenses during the pilot period, totaling $9,915.69.

2025 Projected Cost-Effectiveness

Our estimates indicate that next year, we will become 20 times as cost-effective as cash transfers. As with the previous estimate, this represents immediate impacts on depression upon program completion.

Projected Budget: $313,504

Effect Size: 0.48. This is the effect size in the most recent WHO RCT. We’ve used this rather than our pilot effect size in expectation that our effect size will reduce once we’re operating a larger scale.

Retention Assumption: This estimate assumes that we’re able to maintain our program completion rate of 27%.

The breakdown is as follows:

Cost Per Participant (Regardless of how far they get in the program): $31.35

Cost Per Halfway Completer: $62.70

Cost Per Program Completer: $116.11

Commentary

The pilot version of the program will be the most expensive. Our cost per participant will decrease as we scale. We did not expect the program to be cost-effective right away, and feel this is a strong early result.

However, there are some limitations to our current and projected cost-effectiveness estimates. First, they don’t account for potential lives saved due to preventing suicide. Using subjective well-being as a metric may underestimate the impact of our program given that it might not only improve lives, but save them. Second, to arrive at a true cost-effectiveness estimate, we need to compare the impacts over time, whereas these figures capture the cost-effectiveness only of the immediate benefits gained by participating in the program. We have not yet conducted this more complex analysis.

Program Impacts According to Participants

Numbers can tell us how cost-effective our intervention is relative to other solutions, but they can’t articulate the impacts that reducing depression has for an individual. We administered chatbot surveys and conducted interviews with 30 participants to understand their experience in the program, including how it helped them.

Qualitative interviews revealed that program completers had experienced profound changes in their lives, ranging from improved well-being to regaining control over their lives and advancing in their education and careers. One participant said, “every aspect of my life has changed…this has been like magic in my life.”

Suicidality: A critical impact of our program is the potential that it can save lives. In guide calls or end feedback interviews, four participants explicitly said the program had helped them to reduce or eliminate their suicidal thinking. In the baseline and endline PHQ-9 questionnaires, eight participants who had suicidal thoughts at the beginning replied at the end that they had none.

Emotional Well-Being: Participants consistently noted that they felt better than they did before.

I used to feel stressed and tense. Now there is no problem. I tried the exercises, and now I feel better.

[My guide] guided me, and now everything is normal. I learned to be happy, how to talk to people. Now I stay happy more and sad less.

Everything got better.

Social Interaction: Depression causes people to withdraw from others. Before the program, many of our participants had stopped speaking to their friends or family.

When I started, I was very low and didn’t talk to anyone. I didn’t talk to my friends or go out. Now I interact well.

Earlier, I didn’t like anything, didn’t feel like talking to anyone, or doing any work. Now I do all of those things.

I didn’t talk to anyone, not even at home… But after joining and completing the sessions, I am now in a much better state and talk to everyone and hang out with friends. I eat properly too.

Coping Mechanisms: Participants learned new ways to manage stress and anxiety. A number of participants noted they had learned to calm themselves down.

When I started, I was in a very bad state… As I did the exercises and progressed, my stress reduced and I felt a lot of relief.

It helped me a lot with my nervousness.

There’s a lot of change in overthinking; I don’t do it as much anymore.

I now run my life, unlike before, when it felt like I was controlled by a remote.

Education and Career Advancement: Depression causes difficulty focusing and reduced clarity. Several participants noted that their productivity had increased and they were better able to focus and study.

Earlier, I used to get distracted [when studying], but now it’s much better than before.

I didn’t know what to do in life, but after doing this [program], I started studying to become an electrical engineer.

Helpfulness: A chatbot-administered survey asked program completers if and to what degree the program had helped them. 100% of respondents said they felt it had helped them. 88% of those said it helped a lot.

Part 3. Recruitment

Quick Stats

97% of people who completed the baseline depression questionnaire scored as having depression, with 82% scoring in the moderate to severely depressed range.

875 people sent a message to the chatbot in one month of advertising. We spoke to similar organizations who took a full year to acquire 1K users.

12% conversion rate from sending an initial exploratory message to appearing at the first guidance call. This conversion rate is almost unheard of: in the for-profit sector, 2% would be considered very good, and unlike for-profits, we actively filtered people out (if they scored below moderate to severe depression, they were directed to a flow to complete the program independently).

$105 total spending ($0.96 per person) was how much it cost to recruit our target number of participants, almost exclusively through Instagram ads (i.e. minimal staff time was required).

Individuals had to be interested enough in joining the program to fulfill each of the steps in the process below, each of which represents a dropout point. 12% of people who sent an initial message to the bot- knowing little about the program- completed all of these steps and were moderately to severely depressed.

Participant Profile

We were surprised to find that we reached youth from lower-income backgrounds even though we didn’t use specific recruitment tactics to reach them.

Participants held professions such as domestic worker, informal shop owner, construction worker, and factory worker

During guide calls, 17% of participants explicitly discussed financial issues as a major source of stress in their lives

2⁄3 of participants came from Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities* even though our advertising also targeted megacities such as Delhi and Mumbai

Guides perceived that the majority of our participants were from underprivileged backgrounds

The interest in this program among less privileged individuals, even though the ads were marketed equally to wealthy individuals, may be an indicator that there truly is a greater need for mental healthcare among those with fewer resources. There was a spectrum, however; there were higher-income individuals in the program as well. These participants held positions such as engineer, graphic designer, and accountant. In terms of gender, participants were 60% male and 40% female.

Overall, we consider recruitment to be one of the biggest successes of the pilot. We successfully recruited our target group for a low cost, in a short timeframe, with minimal staff effort.

*“Tiered” cities is a term which refers to smaller cities. It’s a widely-held belief in India that smaller cities have much fewer resources than very large“Tier 1” cities.

Part 4. Retention

27% of participants completed all of the program content*. The WHO’s most recent RCT saw completion of 32%. We are pleased with this result: we didn’t expect to get close to the WHO’s retention on our first attempt with an MVP, given that the WHO’s program went through years of iteration.

Engagement with mental health apps is typically extremely low. The general consensus among actors in the industry is that less than 1% of users sustain their engagement beyond the first month**, let alone go beyond engagement to consistently practice the exercises they learn. In comparison, we engaged users over the course of months and successfully drove behavior change.

Guide call retention was higher than program content completion. 36% of participants completed at least four guide calls, which represents the halfway point. This may indicate that participants enjoyed the guide calls more than the program content, or found it easier to participate in calls than independently engage with the content.

We interviewed partial completers to understand why they did not continue the program. Three participants cited reasons that were related to the program: one was already familiar with a lot of what was being taught, another found it boring, and the third “could not get themselves to talk to people.” All other partial completers gave reasons related to life circumstances, including being too busy, having too much work or studying to do, going back home to their village, or family issues such as health problems or a death in the family.

*The WHO considers a participant to have completed the content if they finish Section 4 of 5. We use the same benchmark so we can compare with their retention.

**We can’t directly compare our retention to that of apps since we measure engagement from different starting points and apps typically don’t filter people out like we do. However, this can give a sense of the context in which we’re operating.

Part 5. Participant Feedback

We conducted in-depth interviews 22 program completers and 8 partial completers* to understand their experience in the program.

Acceptability: Program completers were satisfied with the program overall. In a chatbot survey, 96% said they were likely or very likely to recommend the program to a friend or family member.

Preferences: When asked what the best part of the program was- videos, exercises or guide calls- 57% of interviewed participants chose guide calls. 24% liked the videos best, and 19% liked doing the exercises best.

Guide Calls: Participant feedback on the guide calls was overwhelmingly positive. One participant referred to the calls as “the highlight of my program.” Another emphasized they completed the program because of their guide. Participants described the guides as “really nice to talk to”; “like a friend or elder sister”; “having a familial sense of belonging”′ “very sweet”; “supportive”; “understanding”; and “empathetic.” One participant said they “didn’t feel like they were talking to a stranger.” Participants also felt supported by their guides: one participant said, “I felt like someone was thinking about me” and another said it was “nice to see someone caring for me.” A third participant said their guide “made me feel like I belonged and gave me courage.” One participant believed “75% of my result is due to my guide.” This commentary gives the sense that guide calls do play a major role in sustaining participant engagement.

Negative comments related to guides focused almost exclusively on the desire to interact with them more. Some participants wanted calls at a greater frequency, for calls to be longer, and to be able to speak with their guides after the program.

Videos: Feedback on the videos was mixed. Participants who liked the videos said they could relate to the characters and their stories. They also liked that the videos were very clear and easy to understand. Participants who disliked the videos said they felt slow and repetitive; that the videos were similar and so become boring over time.

Exercises: Program completers said they found the exercises helpful. One participant said the exercises “are a part of how I function now.” Another said they found them effective in dealing with stress; a third found them “helpful and peaceful.” One participant felt the exercises helped them control their anger issues. There was no clear negative feedback on the exercises, but there were signs of lack of engagement with some exercises. When asked which exercises they planned to continue using, most participants named the breathing and grounding exercises, both of which are simple meditative stress reduction techniques. A few exercises weren’t mentioned at all.

Chatbot: Feedback on the chatbot was neutral. Participants often used the word “okay” when describing the bot. Positive comments were related to the bot’s tone- calm, polite, soft, caring, and friendly were among the descriptors. On the negative side, participants felt the bot was too robotic and disliked that it gave them repetitive responses.

*We attempted to reach more partial completers for longer interviews but could not. It’s notoriously difficult to get feedback from people who disengage.

What’s Next

The pilot worked. It demonstrated both feasibility and acceptability. We reached our target population, they liked the program, and most importantly, their depression reduced. We are heartened by the results we’ve received, but are cognizant that there’s much work ahead of us. The response from participants showed us viscerally how deep the need is. 200 million people in India suffer from a mental health disorder at any given point in time, and our experiences in the pilot have only strengthened our resolve to grow fast enough and big enough to meet the need as much as we can. We are continuously growing the program and working toward our goal to reach millions of youth who would not get care for their depression without us.

How to Donate

If you’d like to support our work, please donate at this link or contact Rachel Abbott at rachel@kayaguides.com. Per our most recent assessment, it costs us $96 to provide mental healthcare to a person in need of help. Any level of donation makes a difference to our ability to reach the people most in need of care. We have a gap of $11K to fund our work through the end of this year. Our budget to raise for next year is $313,504.

With questions, interest in supporting us or anything else, reach out to Kaya Guides founder Rachel Abbott at rachel@kayaguides.com, or submit the contact form on our website.

*This post was edited to add to the executive summary that the pilot did not have a control group and to mention the spontaneous remission rate of the control group in the WHO RCT. How to donate was removed from the executive summary. More information was added about participants’ profiles. A sentence in the “Takeaway” section was revised to more accurately reflect the organization’s view on what the pilot results signify. A comparative reference to two studies of therapy-driven programs was removed. Phrasing related to a comparison to Step-by-Step was adjusted to note that the effect sizes can’t be directly compared because the populations are different.

Congratulations on your first pilot program! I’m very happy to see more work on direct well-being interventions!

I have a few questions and concerns:

Firstly, why did you opt to not have a control group? I find it problematic that you cite the reductions in depression, followed by a call to action for donations, before clarifying that there was no control. Given that the program ran for several months for some participants, and we know that in high income countries almost 50% recover without any intervention at all within a year[1], this feels disingenuous.

Secondly, isn’t it a massive problem that you only look at the 27% that completed the program when presenting results? You write that you got some feedback on why people were not completing the program unrelated to depression, but I think it’s more than plausible that many of the dropouts dropped out because they were depressed and saw no improvement. This choice makes stating things like “96% of program completers said they were likely or very likely to recommend the program” at best uninformative.

Thirdly, you say that you project the program will increase in cost effectiveness to 20x cash transfers, but give no justification for this number, other than general statements about optimisations and economies of scale. How do you derive this number? Most pilots see reduced cost-effectiveness when scaling up[2], I think you should be very careful publicly claiming this while soliciting donations.

Finally, you say Joel McGuire performed an analysis to derive the effect size of 0.54. Could you publish this analysis?

I hope I don’t come off as too dismissive, I think this is a great initiative and I look forward to seeing what you achieve in the future! It’s so cool to see more work on well-being interventions! Congratulations again on this exciting pilot!

Whiteford et al. (2013)

There are many reasons for this, see f.ex. “Banerjee, Abhijit V., and Esther Duflo. Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty. PublicAffairs, 2011.” or “List, J. A. (2022). The Voltage Effect: How to Make Good Ideas Great and Great Ideas Scale. Random House.”

Hi Håkon, thank you for these questions!

Pilots typically are meant to indicate whether the intervention may have potential, mainly in terms of feasibility; ours certainly isn’t the definitive assessment of its causal effect. For this we will need to run an RCT. I intended it to be clear from the post that there was no control group but rereading the executive summary, I can see that indeed this was not clear in this first section given that I mention estimated effect size. I have revised accordingly, thanks for pointing this out. We decided not to have a control group for the initial pilot given the added logistics and timeline as well as it being so early on with a lot of things not figured out yet. I’ve removed the how to donate section from the summary section to avoid the impression that is the purpose of this post, as it is not. The spontaneous remission seen in the WHO RCT is noted in “reasons to be skeptical,” but I’ve added this to the executive summary as well for clarity. There’s a lot to consider regarding the finding of a 50% spontaneous remission rate in high-income countries (this post does a good deep-dive into the complexities https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/qFQ2b4zKiPRcKo5nn/strongminds-4-of-9-psychotherapy-s-impact-may-be-shorter), but it’s important to note that the landscape for mental healthcare is quite different in high-income contexts compared to LMIC contexts; people in high-income countries have alternative options for care, whereas our participants are unlikely to get any other form of help.

On the second point, it’s certainly possible that many people stopped engaging because they were not seeing improvements. I have shared the feedback we have so far. We are continuing to collect feedback from partial completers to learn more about their experiences and their reasons for deciding not to continue. It’s important to also understand the experiences of program completers and if/how they’ve benefited from the program, so we’ve shared the feedback.

On your third point, the justification is in the section “2025 Projected Cost-Effectiveness.” The figure is based on the cost-effectiveness estimate on the WHO RCT’s effect size and our projected budget for next year.

Regarding Joel’s assessment, Joel has said his availability doesn’t allow for a formalized public-facing assessment at this time, but the Happier Lives Institute is doing a much more in-depth analysis that they’ve said they aim to publish in 2024.

Thanks again for the critical read and input!

Thanks for making these changes and responding to my concerns!

Also great to hear that HLI is doing a more in-depth analysis, that will be exciting to read.

With regards to the projections, it seems to me you just made up the number 10 000 participants? As in, there is no justification for why you chose this value. Perhaps I am missing something here, but it feels like without further context this projection is pretty meaningless.

My guess is that a WhatsApp-based MH intervention would be almost arbitrarily scalable. 10 000 participants ($300,000) may reflect the scale of the grants they are looking for.

I don’t understand what you are saying here, could you elaborate?

I’ll rewrite completely because I didn’t explain myself very clearly

10,000 participants is possible since they are using Whatsapp, in a large country, and recruiting users does not seem to be a bottleneck

10,000 participants is relevant as it represents the scale they might hope to expand to at the next stage

Presumably they used the number 10,000 to estimate the cost-per-treatment by finding the marginal cost per treatment and adding 1⁄10,000th of their expected fixed costs.

So if they were to expand to 100,000 or 1,000,000 participants, the cost-per-treatment would be even lower.

I hope this is not what is happening. It’s at best naive. This assumes no issues will crop up during scaling, that “fixed” costs are indeed fixed (they rarely are) and that the marginal cost per treatment will fall (this is a reasonable first approximation, but it’s by no means guaranteed). A maximally optimistic estimate IMO. I don’t think one should claim future improvements in cost effectiveness when there are so many incredibly uncertain parameters in play.

My concrete suggestion would be to rather write something like: “We hope to reach 10 000 participants next year with our current infrastructure, which might further improve our cost-effectiveness.”

I run another EA mental health charity. Here are my hastily scribbled thoughts:

When psychotherapy interventions fail, it’s usually not because they don’t reduce symptoms. They fail by failing to generate supply / demand cost-effectively enough, finding pilot and middle stage funding, finding a scalable marketing channel, or some other logistical issue.

Given that failing to reduce symptoms is not that bigger risk, we and every other EA mental health startup I can name did not use a control group for our pilots. Doing so would increase the cost of recruitment by ~10x and the cost of the pilot by ~30% or so.

The #1 reason is that so long as you’re using an evidence-based intervention, cost explains most of the variance in cost-effectiveness.

It’s also possible that they started feeling better and they didn’t need it any more. IMO, this is a little tangential because most dropout isn’t much to do with symptom reduction, it’s more to do with:

1 - (A lack of) Trust in and rapport with the therapist

2 - Not enjoying the process

3 - Not having faith it will work for them

4 - Missing a few sessions out of inconvenience and losing the desire to continue

It’s somewhat analogous to an online educational course. You probably aren’t dropping out because you aren’t learning fast enough; it’s probably that you don’t enjoy it or life got in the way so you put it on the back-burner

This is good point. These statistics are indeed uninformative, but it’s also not clear what better one would be. We use “mean session rating” and get >9/10, which I perceive as unrealistically high. Presumably, this would have gotten around the completer problem (as we’re sampling after every session and we include dropouts in our analysis), but it doesn’t seem it to have. I think it might be because both our services are free, and people don’t like to disparage free services unless they REALLY suck.

Thanks for this thorough and thoughtful response John!

I think most of this makes sense. I agree that if you are using an evidence based-intervention, it might not make sense to increase the cost by adding a control group. I would for instance not think of this as a big issue for bednet distribution in an area broadly similar to other areas bednet distribution works. Given that in this case they are simply implementing a programme from WHO with two positive RCTs (which I have not read), it seems reasonable to do an uncontrolled pilot.

I pushed back a little in a comment from you further down, but I think this point largely addresses my concerns there.

With regards to your explanations for why people drop out, I would argue that at least 1,2 and 3 are in fact because of the ineffectiveness of the intervention, but it’s mostly a semantic discussion.

The two RCTs cited seem to be about displaced Syrians, which makes me uncomfortable straightforwardly assuming it will transfer to the context in India. I would also add that there is a big difference between the evidence base for ITN distribution compared to this intervention. I look forward to seeing what the results are in the future!

Specifically on the cited RCTs, the Step-By-Step intervention has been specifically designed to be adaptable across multiple countries & cultures[1][2][3][4][5]. Although they initially focused on displaced Syrians, they have also expanded to locals in Lebanon across multiple studies[6][7][8] and found no statistically significant differences in effect sizes[8:1] (the latter is one of the studies cited in the OP). Given this, I would be default surprised if the intervention, when adapted, failed to produce similar results in new contexts.

Carswell, Kenneth et al. (2018) Step-by-Step: a new WHO digital mental health intervention for depression, mHealth, vol. 4, pp. 34–34.

Sijbrandij, Marit et al. (2017) Strengthening mental health care systems for Syrian refugees in Europe and the Middle East: integrating scalable psychological interventions in eight countries, European Journal of Psychotraumatology, vol. 8, p. 1388102.

Burchert, Sebastian et al. (2019) User-Centered App Adaptation of a Low-Intensity E-Mental Health Intervention for Syrian Refugees, Frontiers in Psychiatry, vol. 9, p. 663.

Abi Ramia, J. et al. (2018) Community cognitive interviewing to inform local adaptations of an e-mental health intervention in Lebanon, Global Mental Health, vol. 5, p. e39.

Woodward, Aniek et al. (2023) Scalability of digital psychological innovations for refugees: A comparative analysis in Egypt, Germany, and Sweden, SSM—Mental Health, vol. 4, p. 100231.

Cuijpers, Pim et al. (2022) Guided digital health intervention for depression in Lebanon: randomised trial, Evidence Based Mental Health, vol. 25, pp. e34–e40.

Abi Ramia, Jinane et al. (2024) Feasibility and uptake of a digital mental health intervention for depression among Lebanese and Syrian displaced people in Lebanon: a qualitative study, Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 11, p. 1293187.

Heim, Eva et al. (2021) Step-by-step: Feasibility randomised controlled trial of a mobile-based intervention for depression among populations affected by adversity in Lebanon, Internet Interventions, vol. 24, p. 100380.

Very interesting, thanks for highlighting this!

I share your concerns and in our org at least we haven’t improved cost-effectiveness with scale. I think tech orgs though can sometimes be different as Stan said. Even with tech scaling though, ncreases in management staff especially can be a big source of extra costs.

I would like to push back slightly on your second point: Secondly, isn’t it a massive problem that you only look at the 27% that completed the program when presenting results?

By restricting to the people who completed the program, we get to understand the effect that the program itself has. This is important for understanding its therapeutic value.

Retention is also important—it is usually the biggest challenge for online or self-help mental health interventions, and it is practically a given that many people will not complete the course of treatment. 27% tells us a lot about how “sticky” the program was. It lies between the typical retention rates of pure self-help interventions and face-to-face therapy, as we would expect for an in-between intervention like this.

More important than effect size and retention—I would argue—is the topline cost-effectiveness in depression averted per $1,000 or something like that. This we can easily estimate from retention rate, effect size and cost-per-treatment.

I disagree with this. If this were a biomedical intervention where we gave a pill regiment, and two-thirds of the participants dropped out of the evaluation before the end because the pills had no effect (or had negative side-effects for that matter), it would not be right to look at only the remaining third that stuck with it to evaluate the effect of the pills. Although I do agree that it’s impressive and relevant that 27% complete the treatment, and that this is evidence of it’s relative effectiveness given the norm for such programmes.

I also wholeheartedly agree that the topline cost-effectiveness is what matters in the end.

The vast majority of psychotherapy drop-out happens between session 1 and 2. You’d expect people to give it at least two sessions before concluding their symptoms aren’t reducing fast enough. I think you’re attributing far too larger proportion of drop-out to ineffectiveness.

This is fair, we don’t know why people drop out. But it seems much more plausible to me that looking at only the completers with no control is heavily biased in favor of the intervention.

I could spin the opposite story of course, it works so well that people drop out early because they are cured, and we never hear from them. My gut feeling is that this is unlikely to balance out, but again, we don’t know, and I contend this is a big problem. And I don’t think it’s the kind of issue you kan hand-wave away and proceed to casually presenting the results for completers like it represents the effect of the program as a whole. (To be clear, this post does not claim this, but I think it might easily be read like this by a naive reader).

There are all sort of other stories you could spin as well. For example, have the completers recently solved some other issue, e.g. gotten a job or resolved a health issue? Are they at the tail-end of the typical depression peak? Are the completers in general higher conscientiousness and thus more likely to resolve their issues on their own regardless of the programme? Given the information presented here, we just don’t know.

Qualitative interview with the completers only gets you so far, people are terrible at attributing cause and effect, and thats before factoring in the social pressure to report positive results in an interview. It’s not no evidence, but it is again biased in favor of the intervention.

Completers are a highly selected subset of the participants, and while I appreciate that in these sort of programmes you have to make some judgement-calls given the very high drop-out rate, I still think it is a big problem.

The best meta-analysis for deterioration (i.e. negative effects) rates of guided self-help (k = 18, N = 2,079) found that deterioration was lower in the intervention condition, although they did find a moderating effect where participants with low education didn’t see this decrease in deterioration rates (but nor did they see an increase)[1].

So, on balance, I think it’s very unlikely that any of the dropped-out participants were worse-off for having tried the programme, especially since the counterfactual in low-income countries is almost always no treatment. Given that your interest is top-line cost-effectiveness, then only counting completed participants for effect size estimates likely underestimates cost-effectiveness if anything, since churned participants would be estimated at 0.

Ebert, D. D. et al. (2016) Does Internet-based guided-self-help for depression cause harm? An individual participant data meta-analysis on deterioration rates and its moderators in randomized controlled trials, Psychological Medicine, vol. 46, pp. 2679–2693.

Yes, this makes sense if I understand you correctly. If we set the effect size to 0 for all the dropouts, while having reasonable grounds for thinking it might be slightly positive, this would lead to underestimate top-line cost effectiveness.

I’m mostly reacting to the choice of presenting the results of the completer subgroup which might be conflated with all participants in the program. Even the OP themselves seem to mix this up in the text.

As far as I can tell, they are talking about completers in this paragraph, not participants. @RachelAbbott could you clarify this?

When reading the introduction again I think it’s pretty balanced now (possibly because it was updated in response to the concerns). Again, thank you for being so receptive to feedback @RachelAbbott!

Congratulations on the pilot!

I just thought I’d flag some initial skepticism around the claim:

Overall I expect it may be difficult for the uninformed reader to know how much they should update based on this post (if at all), but given you have acknowledged many of these (fairly glaring) design/study limitations in the text itself, I am somewhat surprised the team is still willing to make the extrapolation from 7x to 20x GD within a year. It also requires that the team is successful with increasing effective outreach by 2 OOMs despite currently having less than 6 months of runway for the organisation.[1]

I also think this pilot should not give the team “a reasonable level of confidence that [the] adaptation of Step-by-Step was effective” insofar as the claim is that charitable dollars here are cost competitive with top GiveWell charities / have good reason to believe you will be 2x top GiveWell charities next year) (though perhaps you just meant from an implementation perspective, not cost-effectiveness). My current view is that while this might be a reasonable place to consider funding for non-EA funders (or e.g. specifically interested in mental health or mental health in India), I’d hope that the EA community who are looking to maximise impact through their donations in the GHD space would update based on higher evidentiary standards than what has been provided in this post, which IMO indicates little beyond feasibility and acceptability (which is still promising and exciting news, and I don’t want to diminsh this!)

I don’t want this to come across as a rebuke of the work the team is trying to do—I am on the record for being excited about more people doing work that use subjective wellbeing on the margin, and I think this is work worth doing. But I hope the team is mindful that continued overconfident claims in this space may cause people to negatively update and less likely to fund this work in future, and for totally preventable communication-related decisions, and not because wellbeing approaches are bad/not worth funding in principle.

A very crude BOTEC based only on the increased time needed for the 15min / week calls with 10,000 people indicates something like 17 additional guides doing the 15min calls full time, assuming they do nothing but these calls every day. The increase in human resources to scale up to reaching 10,000 people are of course much more intensive than this, even for a heavily WhatsApp based intervention.

10000 * 0.25 * 6 * 0.27 / 40 / 6 = 16.875

(number reached * hours per week * weeks * retention / hours per week / week)

Hi Bruce! Our minimum target for this year is to help 1K people, so we’d be moving from at least 1K this year to 10K participants next year. Based on our budget projections, it should be feasible to help 10K people for a budget of approximately $300K per year. We believe it is feasible to raise this amount. If I understand correctly, I think when you say effective outreach, you’re referring to participant acquisition. If we maintain the acquisition cost of $0.96 per participant, it would cost around $10K to acquire 10K participants; spending this amount would be feasible. However, in addition, we are beginning to build out other recruitment pathways such as referrals from external organizations and partners, which can bring in many people without additional costs besides some staff time. We’re also optimistic that we’ll start to see organic growth beginning this year.

We’ve used a more conservative estimate for effect size next year. The estimated effect size for the pilot was 0.54 standard deviations but we believe this is an upper bound and don’t expect to maintain it, so we’ve used the WHO’s effect size of 0.48 standard deviations. We chose this effect size because it’s the best evidence we have. It may prove to be an overly optimistic estimate. Maybe the pilot results were a fluke and we won’t even get close.

It is a fair point that the statement about our confidence level might be too high; I’ve revised it to more accurately reflect the meaning I intended to get across (“The pilot outcomes suggest that this program can be implemented successfully on WhatsApp and may indicate that our adaptation of Step-by-Step has been effective, although much more data is required to confirm this”).

I agree with you that the main takeaway should be that the pilot demonstrates acceptability and feasibility, not that it’s a highly cost-effective intervention; there is not enough evidence for this. The purpose of the pilot was always to test acceptability and feasibility, while collecting data on end impacts to generate some early indicators of its effectiveness. On the note of donors- for funders who want to focus their charitable donations on interventions with well-established cost-effectiveness, I would not advise them to support us at this time. An organization in its second year is highly unlikely to be able to meet this bar. Supporting our work would be a prospect for donors who are interested in promising interventions that could potentially be very cost-effective, but need to grow to a point where there is enough data to confirm this.

I focused a lot of the content of the post on the tentative results we have on the end impact of the intervention because I know that is the primary interest of forum readers and the EA community in general. However, in retrospect, perhaps I should have focused the post mostly on acceptability and feasibility, with a lesser focus on the impact, given that testing A&F was the primary purpose of the pilot.

Thanks for the comments, these are all reasonable points you’ve made. Cheers!

Executive summary: Kaya Guides ran a pilot in India of a WhatsApp-based guided self-help program to reduce depression, showing promising results including 72% of completers experiencing 50%+ reduction in depression scores, but further research with a control group is needed to establish the program’s true impact.

Key points:

Kaya Guides adapted the WHO’s proven digital guided self-help program to reduce depression in India via WhatsApp, targeting young adults with moderate to severe depression.

In the pilot with 103 participants, 72% of completers had a 50%+ reduction in PHQ-9 depression scores and 36% became depression-free, a strong result compared to therapy benchmarks, but there was no control group.

The pilot’s estimated effect size of 0.54 is promising but likely an upper bound. More research is needed to establish the program’s impact.

The pilot was estimated to be 7x more cost-effective than cash transfers at improving subjective well-being. Cost-effectiveness is projected to increase to 20x next year.

Participants reported major positive life impacts, and the program successfully reached the target demographic of lower-income Indian youth.

Engagement and retention were strong for a digital mental health program. Participants gave positive feedback, especially on the guided support calls.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.