Tensions between different approaches to doing good

Link-posted from my blog here.

TLDR: I get the impression that EAs don’t always understand where certain critics are coming from e.g. what do people actually mean when they say EAs aren’t pursuing “system change” enough? or that we’re focusing on the wrong things? I feel like I hear these critiques a lot, so I attempted to steelman them and put them into more EA-friendly jargon. It’s almost certainly not a perfect representation of these views, nor exhaustive, but might be interesting anyway. Enjoy!

I feel lucky that I have fairly diverse groups of friends. On one hand, some of my closest friends are people I know through grassroots climate and animal rights activism, from my days in Extinction Rebellion and Animal Rebellion. On the other hand, I also spend a lot of time with people who have a very different approach to improving the world, such as friends I met through the Charity Entrepreneurship Incubation Program or via effective altruism.

Both of these somewhat vague and undefined groups, “radical” grassroots activists and empirics-focused charity folks, often critique the other group with various concerns about their methods of doing good. Almost always, I end up defending the group under attack, saying they have some reasonable points and we would do better if we could integrate the best parts of both worldviews.

To highlight how these conversations usually go (and clarify my own thinking), I thought I would write up the common points into a dialogue between two versions of myself. One version, labelled Quantify Everything James (or QEJ), discusses the importance of supporting highly evidence-based and quantitatively-backed ways of doing good. This is broadly similar to what most effective altruists advocate for. The other part of myself, presented under the label Complexity-inclined James (CIJ), discusses the limitations of this empirical approach, and how else we should consider doing the most good. With this character, I’m trying to capture the objections that my activist friends often have.

As it might be apparent, I’m sympathetic to both of these different approaches and I think they both provide some valuable insights. In this piece, I focus more on describing the common critiques of effective altruist-esque ways of doing good, as this seems to be something that isn’t particularly well understood (in my opinion).

Without further ado:

Quantify Everything James (QEJ): We should do the most good by finding charities that are very cost-effective, with a strong evidence base, and support them financially! For example, organisations like The Humane League, Clean Air Task Force and Against Malaria Foundation all seem like they provide demonstrably significant benefits on reducing animal suffering, mitigating climate change and saving human lives. For example, external evaluators estimate the Against Malaria Foundation can save a human life for around $5000 and that organisations like The Humane League affect 41 years of chicken life per dollar spent on corporate welfare campaigns.

It’s crucial we support highly evidence-based organisations such as these, as most well-intentioned charities probably don’t do that much good for their beneficiaries. Additionally, the best charities are likely to be 10-100x more effective than even the average charity! Using an example from this very relevant paper by Toby Ord: If you care about helping people with blindness, one option is to pay $40,000 for someone in the United States to have access to a guide dog (the costs of training the dog & the person). However, you could also pay for surgeries to treat trachoma, a bacterial infection that is the top cause of blindness worldwide. At around $20 per surgery, you could cure blindness for around 2,000 people – helping 2,000x more people for the same amount of money![1]

For another example, the graph below ranks HIV/AIDS interventions on the number of healthy life years saved, measured in disability-adjusted life years, per $1,000 donated (see footnote for DALY definition).[2] As you can see, education for high-risk groups performs 1,400 times better than surgical treatment for Kaposi’s Sarcoma, a common intervention in wealthy countries. And we can all agree it’s good to help more people rather than fewer, so finding these effective interventions is extremely important to our theory of doing good.

Complexity-inclined James (CIJ): This all sounds great and I totally agree we should help as many people as possible given our resources, but I worry that we will just focus on things that are very measurable but not necessarily the most good. What if other organisations or cause areas are actually producing greater benefits but in hard-to-measure ways? I mean, the very same source you linked about the cost-effectiveness of animal welfare-focused corporate campaigns says as much:

“However, the estimate doesn’t take into account indirect effects which could be more important.”

QEJ: Well if something is beneficial, surely you can measure it! Otherwise what impact is it actually having on the real world? The risk with not quantifying benefits or looking objectively is that you might just have some unjustified emotional preference or bias for some issues, such as thinking dogs are cuter than cows, which pulls you in the direction of actually achieving less on the cause you care about. Motivated reasoning like this is the reason why we often spend so much charity money to help people in our own country. However, if we truly value beings equally, we should be doing our utmost to help people who are the worst off globally, which often means donating to charities working in low-income countries. For example, I’m sure the charities recommended by GiveWell or Giving Green are much more effective than a random global health or climate charity you might pick – again highlighting the benefits of numerical evaluation over intuition alone.

CIJ: Okay, well, let’s take this one point at a time. On your point of understanding the impact of indirect benefits, an example might be achieving wins that have symbolic value, like winning a ban on fur farming, or the government declaring a climate emergency. The number of animals helped or carbon emissions affected directly might be relatively small, but they’re probably important stepping stones towards larger victories.[3] Or by simply demanding something much more radical, like a total end to all meat and dairy production, you could shift the Overton window such that moderate reforms are more likely to pass. This would certainly be beneficial to the wider ecosystem working on the issue, although the specific organisation in question might get little praise.

QEJ: On your first point, what actually is the benefit of these symbolic wins though? What is it actually good for: do you mean it increases public opinion for further support, or something else?

CIJ: Well yes, it might inspire a bunch of advocates that change is possible, so there is renewed energy within the field, potentially drawing in new people. It could also lead to advocates forming good relationships with policymakers, leading to future wins. It might also mean we get good experience working on passing policy, which might make future more ambitious things go well. Also if there’s media coverage of this, which there usually is, that definitely also seems useful for public support and salience on our issue!

QEJ: Okay, that seems reasonable. But that just seems like a limitation of the current evaluation methodology and something we could actually include in our cost-effectiveness calculations! We will just model flow-through effects and second-order effects, such as the impact of policy on growing the size of a movement, then we can include all these other factors too.

CIJ: Sorry to rain on your parade, but I don’t think your models will ever be able to capture all the complexity in the real world. I think we really are fairly clueless to the true impact of our actions. Even worse, I think sometimes (maybe even often!) these unquantifiable consequences will outweigh the quantifiable consequences, so your model might actually even point in the wrong direction.

QEJ: But then how do you decide which actions you take if you want to do the most good? The problem is that we have very limited resources dedicated to solving important global problems—and we want to use this as best as possible. Saying something like “it’s too complex, we could be wrong anyway” doesn’t seem particularly useful on a practical level for making day-to-day decisions.

CIJ: Yes—I totally agree! It definitely doesn’t feel as satisfying as numbers, but I don’t think life is that simple. It just seems extremely bizarre if all the best ways to do good have easily quantifiable outcomes. Wouldn’t that strike you as a bit suspicious? Especially if you’re a bunch of people with a more quantitative background (e.g. the effective altruism community) – that sounds like motivated reasoning to me!

QEJ: Well, maybe, but I’m still not convinced that there is a better alternative which can provide objective and action-guiding answers.

CIJ: Yes – maybe there isn’t, but whoever said doing good was going to be easy! Maybe it just comes down to having a clear vision of your theory of change and a good understanding of the issues at hand.

I mean social change is extremely complex so wouldn’t you think it’s slightly naive to think we can significantly change the world by pursuing a very narrow quantifiable set of approaches? I mean sure, corporate welfare campaigns create extremely impressive measurable good to help animals, but it’s still not clear that they’re actually the most cost-effective animal charity.

QEJ: Yes it’s not clear they’re the best, but they seem better than most! How else do you propose we make decisions like this? There are many ineffective organisations, and some of them are probably making the situation even worse. Do you think we should support them all equally?

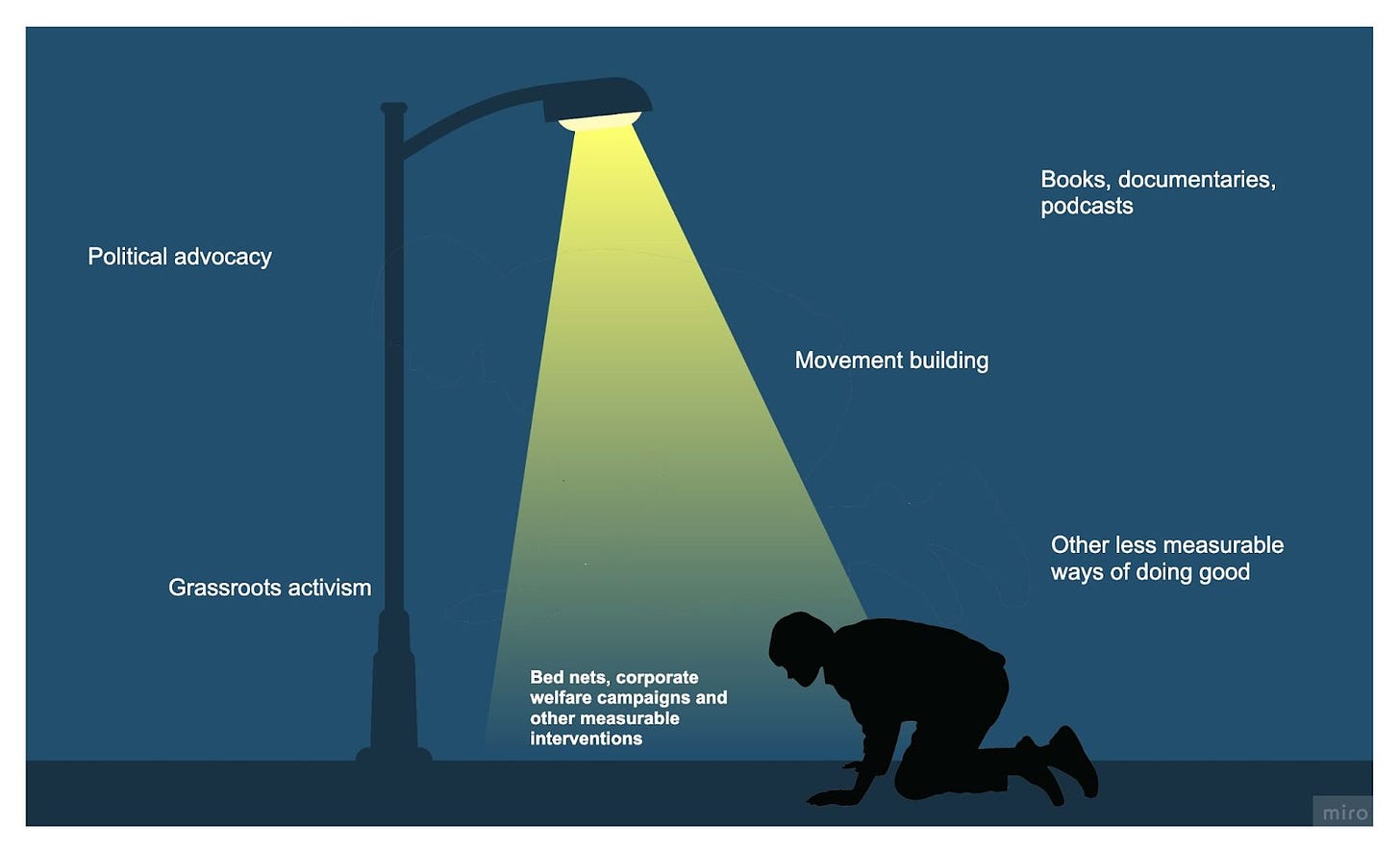

CIJ: Not quite. First, I think we shouldn’t be so quick to discard interventions that are difficult to measure as interventions that aren’t important. As illustrated by this very relevant quote, “Absence of Evidence does not mean Evidence of Absence”. And just because we can see stuff better under a streetlight, it doesn’t mean that it has the stuff we actually want to find!

Additionally, I just think some more epistemic humility might be needed before calling some organisations “the most effective” or even “effective”. Sure, it’s “effective” in achieving some set of narrow metrics, but those metrics often only capture one small part of what is actually required to make progress on the problems we care about. That said, I do agree that measurement and evaluation is important, but that it might just require tools that are not strictly quantitative.

QEJ: Okay fair enough, I take those points. Although I should note, I don’t just think we should focus on measurable things, even though that is definitely useful for feedback loops. I definitely do think we should support things that are more speculative but potentially very high value. Ultimately, what we do care about is maximising expected value—not just high confidence in some positive value. For example, a 10% chance of helping 10 million people (so we would, on average, expect to help 1 million people) is better than a 100% chance of helping 100,000 people. Would you agree with that?

CIJ: Yes definitely! This has the same problem though—you’re forced to quantify the benefits and in doing so, you could miss out on potentially many important effects. The immeasurable (either literally or practically) effects are likely larger than the measurable effects, and they could easily change your bottom-line answers. Therefore, maximising expected value is unlikely to happen by naively maximising estimated expected value. There are many reasons we can’t take expected value calculations seriously. For example, we saw what happened when Sam Bankman-Fried (probably) made naive expected value calculations when considering how much money he could make via fraud. As others might do, he neglected the less tangible negative consequences, such as those on the Effective Altruism movement he was reportedly supporting. In this case, that looked like widespread negative press coverage in the following months, potentially leading to many people not wanting to get involved with the effective altruism community, a loss in future donors or otherwise painting it in a bad light for influential actors. Before the FTX incident, these negative outcomes would have been almost impossible to quantify accurately, but this didn’t make them any less real (or bad).

QEJ: Ah, well of course we’re against naive consequentialism! It’s paramount that we have as solid a grasp on the issues as possible, and take actions that maximise our potential benefits whilst limiting the negative consequences. Sam’s failure was simply one of not fully understanding the risks and benefits involved (as well as not wanting to obey common-sense morality, as most effective altruists advocate for).

CIJ: This we can definitely agree on. But it just seems to be interesting which speculative bets one prioritises, when considering this expected value approach. For example, you might prioritise somewhat speculative technological solutions to global problems, such as cultured meat or carbon capture & storage. Then when other people advocate for speculative political solutions to our society, such as reforming our political or economic system, they get called “idealistic”. Surely both parties are being idealistic, and the main difference is our starting beliefs, and what we’re being idealistic about?

QEJ: Hm, I think it’s more nuanced than that. We can actually write out a concrete and tangible story why technological solutions like cultured meat and carbon capture will actually lead to good. For example, inventing cultured meat could essentially displace all animal meat with nothing else but simple market forces if it tasted the same, was cheaper and more accessible. How the hell would “bringing down capitalism” lead to the same thing?

CIJ: Well, leaving aside the argument that people’s food choices are much more complex than just price, taste and accessibility, I think your approach feels like a local optimum, rather than a global optimum. In your world, we would still have unsustainable levels of resource consumption, lack of concern for the environment or other species, as well as many other social ills, such as inequality and poverty. These issues, be it climate change, animal suffering or global poverty, can be seen as symptoms of large issues facing our society. These broader systemic issues (e.g. around the misallocation of capital in our economy or myopia of elected political leaders) won’t be solved simply by addressing these symptoms. Instead, we do need much broader political and economic reforms, whether that’s more deliberative democracy, prioritising wellbeing over GDP, and so on. This is what we often mean when we say “changing the system” or “systemic change” – things that would quite fundamentally reshape modern politics and our economy. We’re not simply referring to what effective altruists have previously called “systemic change”, which seems to refer simply to any act that changes government policies (i.e. the political system).

QEJ: Well, of course it would be great to create an economic system that prioritises well-being and we can ensure that no human lives in poverty, but it’s just not realistic. I mean what are the chances that the current set of political and economic elites will concede enough power such that this actually happens? I think it’s basically 0.001% in our lifetimes.

CIJ: I’m sure critics of Martin Luther King said something broadly similar when he was trying to win voting rights for black people in the 1960s: that he was being too bold, asking for too much, and he would be effective if he made more moderate asks. But looking back now, it clearly worked, and has made the world an immeasurably better place as a result of his and other civil rights activism. What’s to say we can’t achieve similarly large changes to our political & economic systems in our lifetimes?

You might assign it a probability of 0.001% such that it’s highly unlikely to happen, but I think it could be more like 0.1%. And like you’ve mentioned, if we’re also valuing low-probability outcomes that could be extremely important, this kind of fundamental restructuring of economic and political priorities seems like a clear winner (in my opinion). Due to the different biases or worldviews we hold, you think technological solutions might be the best thing to pursue, due to their relative tractability, neglectedness and importance, but I can make the same plausible-sounding arguments for “systems change” stuff.

QEJ: Sure, that might be the case. And I take the point that we will all have different biases that lead us to different conclusions. But from my reading of history, when we’ve had rapid societal change (what you might call revolutionary change), this has usually led to bad outcomes. As such, I feel much more positive about making small improvements to our current political and economic systems, rather than wholesale changes. Just look at what happened with Stalin after the Russian Revolution of 1917 and all the bloodshed that caused. Do you want to risk other horrible times like that?

CIJ: Well, there’s a number of reasons why I don’t think that’s the kind of “revolutionary change” we’re after, not least because it was followed by a huge consolidation of political power and a dictatorial regime—the opposite of what I think is good! I do think such larger-scale changes need to be considered thoughtfully, but I also believe moving slowly can be equally as bad or worse. Imagine if we moved slowly on abolishing slavery—what would the world look like today? That was a fundamental change in our economy and how we valued people, similar to how it might be if we might move away from solely prioritising GDP, and I’m sure we all wish that would have happened sooner. Additionally, by never pursuing “step-change” approaches, we might always be stuck at the local optimum, rather than a global optimum.

Ultimately, what I’m saying is that we need a “portfolio approach” of ways to do good, where we’re supporting a wide range of things that could plausibly have huge impacts on the world. Given the vast uncertainties I’ve spoken about, hedging our bets across different worldviews and different theories of change seems like a crucial way to ensure good outcomes across the range of ways the world could turn out.

QEJ: Whilst I might not agree with all of your points, I definitely do agree that we need to pursue a variety of approaches to achieve change. At least we can agree on something!

— end dialogue—

Obviously, this is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of some disagreements these two types of worldviews might have with each other! It could go on and on, but I’m not sure I could ever do it justice. For example, there could be a whole other dialogue or section on the value of democracy, the benefits of different ways of thinking, and how socio-demographic diversity might support better decision-making. Regardless, I hope it was at least somewhat enlightening in terms of how these two different camps may think.

For additional reading on different ways of doing good, I recommend a great blog post by Holden Karnofsky, called Rowing, Steering, Anchoring, Equity, Mutiny. It presents an interesting typology of different ways people are trying to improve the world, using the analogy of the world as a ship, seen in the table below.

- ^

I’m assuming that the $20 dollars per surgery includes operational costs & overhead but even if not, the difference is still very large.

- ^

A DALY is a disability-adjusted-life-year, a common measure used to quantify how beneficial some interventions are, based on how many additional years of healthy life they provide.

- ^

In terms of relative proportions, whilst there might be around 100 million animals farmed for their fur annually (which is terrible) there are around 80 billion vertebrate land animals killed for food each year.

Hey James, thanks for posting this! I really liked your steelman of “Complexity-inclined James”. I think EAs should always be considering other perspectives, and being able to understand where others come from is incredibly important—especially critics, and especially those where both sides can be made better off through good-faith dialogues, even if we still disagree.

I get that this is the very tip of the iceberg, but I’ve got a few points that I’d like to hear your thoughts on:

In practice, those on the side of CIJ are usually a lot less epistemically humble and more vitriolic than he is. Not all of them, of course, but many of them aren’t calling for a ‘portfolio approach’ at all, but their approach. Cluelessness cuts both ways! And many activist critics of EA don’t seem to apply cluelessness concerns to their own theories of change.

I don’t quite think “looking under the streetlight” is a fair characterisation of the problem. I think it’s more like a Multi-Armed Bandit approach, where AMF is the top-scoring bandit[1] and it does pretty well, and options CIJ is looking at moving towards (‘protest’, ‘building class consciousness’, ‘put the whole system on trial’) look quite dubious in comparison. Tl;dr: Saving someone’s life from malaria is not a ‘narrow metric’ imo

Finally, I think you underestimate the extent to which a significant part of the community would actually be in favour of various kinds of systemic changes and interventions! My intuition is that people are very uncertain about what to propose here, cautious about backfiring effects from them, and in general may lack the experience and skills to make significant progress on them at the moment.

In any case, I liked the post, and look forward to seeing more posts from you along these lines :)

Adjusted to your most-effective option accordingly

Adding that when I first did EV estimates of successful protest/activist movement that:

Activism is never really convenient or “high-EV”. I think the public generally holds contradictory and unrealistic expectations of activism. For one, it’s very easy to put off activism as “not a priority” because it doesn’t lead to obvious career/monetary benefit and always costs time and poses perceived reputation risk. Whenever I hear someone say they care about a cause but don’t have time to advocate for it, I just tell them they’ll never find a better time. A busy, career-focused 20 year old becomes a busy, career-focused 30 year old becomes and busy, career-focused 40 year old then they forget whatever they cared about. There’s a reason EA skews so young, time works against wanting to do meaningful things.

Activism is almost always either controversial/untractable or unnecessary. For the simple reason that if everyone’s already convinced of an idea, you don’t really need activism. Progress would, by definition, be crucial on issues that seem controversial or so niche that it seems people will “never understand”. So when someone tells me that issue [X] is unpopular/controversial/too obscure, I’m like … yeah, that’s the point. Of course the current discourse makes progress seem untractable, that’s how all activism starts out and aims too induce beliefs away from. Perhaps more annoying is when activists spend years being harassed and dismissed, then when the Overton Window finally shifts, people just accept the ideas as obvious/default and go back to dismissing the value of activism for the next topical issue, without acknowledging the work done to raise the sanity waterline.

I think these paradoxes are hard to explain to people, because if one never engages/participates in activism, it’s very easy to be cynical and dismiss activism as frivolous/misguided/performative. Which is as true as dismissing EA orgs with “I read somewhere that nonprofits are just a way for rich people to launder money while claiming admin costs”.

Sigh, oh well.

I agree that activism in particular has a lot of idiosyncrasies, even within the broader field of systems change, that make it harder to model or understand but do not invalidate its worth. I think that it is worthwhile to attempt to better understand the realms of activism or systems change in general, and to do so, EA methodology would need to be comfortable engaging in much looser expected value calculations than it normally does. Particularly, I think a separate system from ITN may be preferable for this context, because “scope, neglectedness, and tractability” may be less useful for the purpose of deciding what kind of activism to do than other concepts like “momentum, potential scope, likely impact of a movement at maximum scope and likely impact at minimum or median scope/success, personal skill/knowledge fit, personal belief alignment” etc.

I think it’s worth attempting to do these sorts of napkin calculations and invent frameworks for things in the category of “things that don’t usually meet the minimum quantifiability bar for EA” as a thought exercise to clarify one’s beliefs if nothing else, but besides, regardless of whether moderately rigorous investigation endorses the efficacy of various systems change mechanisms or not, it seems straightforwardly good to develop tools that help those interested in systems change to maximize their positive impact. Even if the EA movement itself remained less focused on systems change, I think people in EA are capable of producing accurate and insightful literature/research on the huge and extremely important fields of public policy and social change, and those contributions may be taken up by other groups, hopefully raising the sanity waterline on the meta-decision of which movements to invest time and effort into. After all, there are literally millions of activist groups and systems-change-focused movements out there, and developing tools to make sense out of that primordial muck could aid many people in their search to engage with the most impactful and fulfilling movements possible.

We may never know whether highly-quantifiable non-systems change interventions or harder-to-quantify systems change interventions are more effective, but it seems possible that to develop an effectiveness methodology for both spheres is better than to restrict one’s contributions to one. For example, spreading good ideas in the other sphere may boost the general influence of a group’s set of ideals and methodologies, and also provide benefits in the form of cross-pollination from advances in the other sphere. If EA maximizes for peak highly-quantifiable action, ought there to be a subgroup that maximizes for peak implementation of “everything that doesn’t make the typical minimum quantifiability bar for EA”?

Hi James, I just wanted to say that I think this post is great and is a helpful way to understand the different perspectives! I think it’s critical for us to be listening to other groups who are also trying to create a better world.

One idea I have in my mind (that is probably not well thought out at all) is that having a mix of activists and pragmatists might actually be the best solution to create change. In my mind, the activists are the visionaries who paint a picture of how the world could be, and the pragmatists in many cases are slowly making the change happen, across many fronts. Just a stray thought :)

I really enjoy reading your work and think it makes a valuable contribution!

Great post, James! I think you described the 2 positions well.

Some notes:

I like to distinguish between implicit and explicit quantification (which is a matter of degree, not a binary). Whenever we say an intervention A is better, worse or as good as an intervention B, we are implicitly quantifying the goodness of interventions A and B, even if we do not use any numbers, or do any cost-effectiveness analyses.

In this sense, it is possible to quantify the effects of any intervention at least explicitly.

The optimal degree of explicit quantification can vary greatly. For each individual factor which influences the effects of an intervention, I think explicit quantification requires more time, but also leads to better results. So there is a trade-off:

Less quantitative methods allow us to cover more factors, but do not cover them as well as more quantitative ones.

More quantitative methods cover factors better, but cover fewer of them.

I believe it is imporant to have in mind the portfolio approach (or something similar to it) should apply to whole world, not just to the EA community, and definitely not just to each individual. I would say it makes sense for each individual to fully work on / donate to the areas whose marginal cost-effectiveness is higher, because those are the ones whose share in the global porfolio should be increased.