Is the US government insolvent?

Disclaimer: I am not a trained economist. The aim of the post is to start a conversation. If I am wrong about anything please let me know as I am trying to understand my blind spots. I have been interested in Macroeconomics, monetary and fiscal policy for the last few years. I have spent around 2000+ hours reading and listening about the topic. So I’m not an expert but have a good sense. I have moderate certainty about the maths behind the deficit calculations and will indicate where I feel less certain. I’ve chosen to analyze the US government budget here because it’s the most consequential and the data was easiest to find but the majority of governments around the world are in similar situations. This is also my first EA forum post so any feedback is appreciated.

Some parts of the posts were largely taken and paraphrased from the following articles, where I’ve updated some numbers. The authors of these deserve all the credit and I highly recommend reading them for a full understanding:

Acknowledgments: Thank you to two anonymous EAs for their comments and feedback.

Summary

In recent years, due to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and COVID, the debt in major nations has increased to historically high levels that are demonstrably unsustainable. In this short post, I aim to demonstrate that with inflation at decade highs and interest rates at 15-20 year highs, we may have already entered a debt spiral.

The US government currently has $31.3 trillion of debt. The interest expense alone on the debt is $482 billion per year (average 1.5% interest rates). As the debt is repriced at current interest rates (currently ~4%, but let’s take an average of 3%), the interest expense would increase by $500 billion per year to $1 Trillion per year. Additionally, the cost of living adjustments (COLA) to social security etc, combined with decreased tax receipts due to the recession, the annual deficit would organically increase at an unsustainable rate. This suggests the US government is already in a debt spiral, and the only way they can afford to finance the debt is to print money and essentially inflate the debt away.

It seems important for EAs to learn more about this not just to protect themselves against an inflationary decade (although we are currently in a short-term deflationary part of the cycle), but also so that we can consider the second-order consequences to this problem.

The US budget at a glance

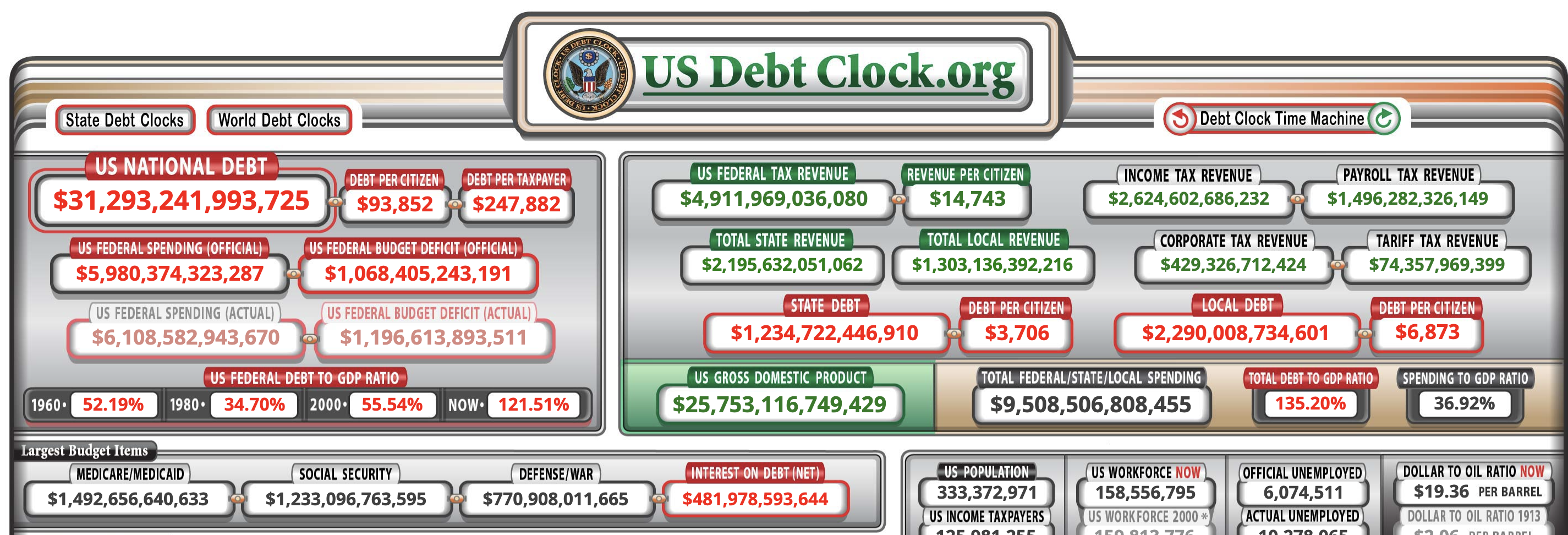

In this section, I will show that when you take the tax revenue (the majority of the revenue to the government) and subtract it by JUST the mandatory and fixed items of spending alone, the US already lack the ability to cover their interest expenses. Lets start by taking a look at the The US debt clock so we can have an overview of the problem:

Pretty staggering.

The US gov tax revenue is $4.9T. According to the CBO (Congressional Budget Office), Mandatory spending will cost $3.7 trillion dollars in 2022. This includes all entitlements and expenditures that are signed into legislation and are considered absolute obligations, such as social security and medicare. Then we add in the estimated $800B of defense spending (which is contractual), and we get a total of $4.5T.

$4.9T revenue - $3.7T entitlements - $800B defense = $400B leftover for interest expense.

The problem is interest expense itself is currently costing $482 Billion dollars. So we have at least $82 Billion in deficit, which means we have to borrow even more money to pay back the extra interest expense that we can’t pay back. Note that this doesn’t even take into account some of the other discretionary spending as well as unfunded liabilities.

As James Lavish (ex-hedgefund manager who writes The Informationist newsletter) puts it:

Think of it like this: You run up the balance on a credit card. The monthly payments are more than you have after paying for mandatory things like mortgage, car loans, and food. So, you take out another credit card to pay for some of these things. But your credit score is worse and the interest rate on this new card is higher. So, now the monthly payments are even higher. And you have borrowed more. To make those payments, you have to open another credit card…and so on…you are trapped.

It’s no different for a country perpetually operating in a deficit.

more debt → higher interest rates → higher deficits → more debt

As it worsens, investors lose confidence in the country and demand higher rates for the country’s bonds, only worsening the situation.

This is also known as the dreaded debt spiral:

But interest rates have gone up a lot...

As you may be aware, the federal reserve has been hiking interest rates at a historically fast pace in order to dampen demand and drive down inflation.

As the government debt reaches maturity, it needs to roll over and be repriced at current interest rates of 4% (but let’s take an average of 3%) - think of this as your fixed-term interest rates on your mortgage running out so you need to renegotiate a new rate with the bank. If we reprice the current $31.3T of debt at 3% interest rates, the interest expense would increase by ~$500 billion per year to almost $1 Trillion per year—That will overtake military spending as the biggest single line item for spending.

Cost of living adjustments (COLA)

It gets worse (from a government debt perspective).

Because of the highest inflation in decades, there will be an upward cost of living adjustments made to spending from social security and other programs, and the CBO projects that this will be 6-9%.

Impacts of the upcoming recession

Although it hasn’t been officially declared, by many indicators and measures, we will be, if not already, entering a recession. During a recession like in 2008 and 2020, government tax revenues tend to fall by 8-10% compared to previous years because of lower capital gains and corporate tax (less earnings); and at the same time, entitlement spending also increases because of the eventual higher unemployment.

Even excluding these additional factors, assuming steady GDP growth and no recessions, you get this ugly chart from the CBO modeled using lower interest rates from earlier this year:

If this was a company, it would be considered straight bankrupt.

Last thoughts

For decades we have been able to sustain higher national debt because interest rates kept falling, so the interest expense remained low.

Now with debt to GDP ratio at 135% and inflation finally running hot causing interest rates to go up, the debt monster may finally catch up to us. As Lyn Alden (macro investor) points out from a letter by Hirschmann Capital:

They found that over the past two centuries, 51 out of 52 countries that reached sovereign debt levels of 130% of GDP ended up “defaulting”, either through devaluation, inflation, restructuring, or outright nominal default, within a pretty wide spread of 0-15 years or so after that point.

Because the US central bank has the ability to create new dollars out of thin air, the US government will almost never hard default on the debt (less certain). In the future, I will write another post about how I expect the US government will pay back this debt, but the short answer here is: The only choice is to let inflation run hot, higher than the stated 2% target, in the hopes to raise GDP and monetize the debt. In other words, use cheaper dollars to pay off old debts. Still only a short-term solution, though, as investors will eventually demand higher Treasury rates in order to be compensated for being paid back in cheaper dollars. It is likely that the federal reserve will have to do some form of quantitative easing again to keep interest rates low. As a result, EAs should learn more about the effects of inflation, and take steps to protect their own purchasing power via investments.

I’m sure others can do a better job responding to this than I can, but a few thoughts:

It’s true that the high US debt/GDP ratio is not harmless, especially insofar as it leaves less fiscal headroom to deal with future recessions, wars etc.

If investors thought the US were likely to need to default or inflate away debt, then 30-year treasury rates would be extraordinarily high (since otherwise they wouldn’t purchase them). That’s the opposite of what we see, where long-run interest rates are less than short-run interest rates.

The US economy is growing faster than inflation. So cost of living adjustments aren’t such a big deal since tax revenue is growing as well

I’d expect US debt to grow much less in a potential upcoming recession than in 2008 or 2020. It made sense to be doing a lot of fiscal stimulus in response to the 2008 financial crisis, but if the fed intentionally triggers a recession as part of controlling inflation, fiscal stimulus doesn’t make as much sense to do.

One more note. You say

This is true of the current budget, but the US could raise taxes to cover interest payments in the future. The US has relatively low taxes compared to other rich countries. Raising the US tax/GDP ratio to that of Germany would raise about $2T more per year in taxes than the US currently takes in.

Not all the debt matures at the same time, does it? If not then maybe only the portion that matures gets repriced?

Correct, that’s why it says

My understanding is that persistent higher inflation may actually be very good for the U.S. government as it’ll essentially erode the debt as inflation eats away at the value of the loans, so that should be taken into account. Of course, it’s bad for stability, especially if you runaway inflation, but with high employment mitigating some of the downside this seems like a major positive factor for the U.S. gov given the amount of debt it holds.

Edit to add: Thanks for taking the time to write this up, found it enjoyable and was a fun thought experiment!

https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2022/aug/inflation-real-value-debt-double-edged-sword#:~:text=An%20increase%20in%20the%20price,higher%20prices%20increase%20nominal%20GDP.

So are you shorting US stonks or the USD?

At this point I’d think higher interest rates have knocked many overinflated stonks down to a reasonable level (at least based on the bloodbath that is the tech stock market over the last few months), that’s not to say of course that other risks haven’t been adequately priced in… like the most valuable company in the world for instance being hugely dependent on the manufacturing of a geopolitical competitor to the U.S.

Firstly, I want to flag that this prediction is in strong disagreement with market predictions: the rate on a 20-year treasury is 3.85% as I write this, suggesting that investors do not expect a dramatic increase in inflation. This is in one of the largest, most liquid, and most attended-to markets on the planet, the only competition I am aware of being other US Government bonds.

Secondly, the weighted average maturity of US government debt is around five years, to give a concrete value for thinking about how long the US government can have much higher inflation before markets are able to fully react. That’s a moderate amount of time, but if you say that the US government is willing to accept multiple years of 15% inflation (an extremely bold claim), you could still only get a temporary 50% reduction in the debt without fixing the underlying entitlement issues.

Which is why it is very strange that this post assumes as a hard constraint that the US government will fulfill its entitlement obligations. I’m not sure why that is assumed. Faced with the option set “inflation” and “cut Medicare and Social Security”, the government might easily choose Medicare and Social Security. Yes, there have been promises, but they are not very credible. Maybe the inflation target gets set to 3% or 4%, numbers that are still very small, but cuts to the commitments seem as or more plausible as spending expands.

Once you drop that assumed constraint, the option set of the government expands to a wide variety of more acceptable solutions.

Finally, “Inflation is going to be terrifyingly high any day now: buy gold/crypto/my special security” has been a recurrent promise of financial snake oil salesmen for decades. Always be careful when you see people claiming it, particularly if they’re also selling something. Debt fears have a similar pedigree: we might be told to be terrified of 130% now, but I remember back when it was 90%, which turned out to be an Excel error.

They might be right this time, but you should look for a lot more than a single analysis without theoretical justification, which relies heavily on datapoints following legendarily expensive wars. In the period since the 1950s, attitudes towards government defaults have shifted. Monarchies act differently from independent central banks.

I agree with the overall reasoning for why we need inflation hedges.

I also agree that US debt poses a risk, as all debts do, but I would view this risk slightly differently, using a historical rather than budgetary lens:

to a large degree, the privilege of the dollar is due to the US being the largest economy, the major world power and a stable government. That makes it “too big to fail”

eventually, the US will not be the largest economy / major world power (looking at history you have to make a strong bet against permanent supremacy). At that point, it will have to come back to Earth and make much more constrained choices like all the other countries have to

this course of events is unlikely to happen because some Fed decision about the timing of interest rates, or because some politician in the 2020s refused to cut back entitlements by a small percentage. It will happen because some other country starts to be seen as the safer option. Prolonged GDP decline, a major military defeat, and/or government overthrow could all help precipitate such an outcome.

The reason this matters is that typical US debt hawks will advocate as a main solution reduced spending on long-term infrastructure, military technology and so on.

However, if you’re concerned with debt, you should be more concerned about GDP (what you get out of the dollar) than government spending (what you put into it, so to speak); about military power than military leanness;and about government stability than government drama (including periodic debt ceiling freakouts). A strong government backed by a strong share of the world economy—that is what investors see in the US dollar. The minute they stop seeing that, the party is over and hard choices will need to be made. (Remember how the markets reacted to Liz Truss’s budget a few months ago? That is what a former empire making economic decisions looks like.)

So if you keep GDP running, prevent China from overturning the world order, and avoid obvious own-goals such as January 6 style craziness the US should be fine for a while longer.

Now, is this US-favourable outcome the most beneficial to the world? I don’t know—it may be better to shift the equilibrium at some point (though on balance, I would tend to say, probably not now). But if it is the outcome you want, those would be the key items to safeguard.

The public debt to GDP ratio in Japan is over 260% and they still haven’t defaulted (it somewhat boggles my mind that they can sustain such high debt levels even though it seems that there are reasonable explanations for it). There are ostensibly some differences between the Japanese and American contexts but nonetheless it seems possible for developed countries to sustain high levels of public debt for a considerable amount of time. I think how long of a time is still an open question. I’d expect to see the Japanese situation unravel before the American one and maybe that might give an indication of how sustainable extreme high levels of debt are if there is ever such an unraveling.