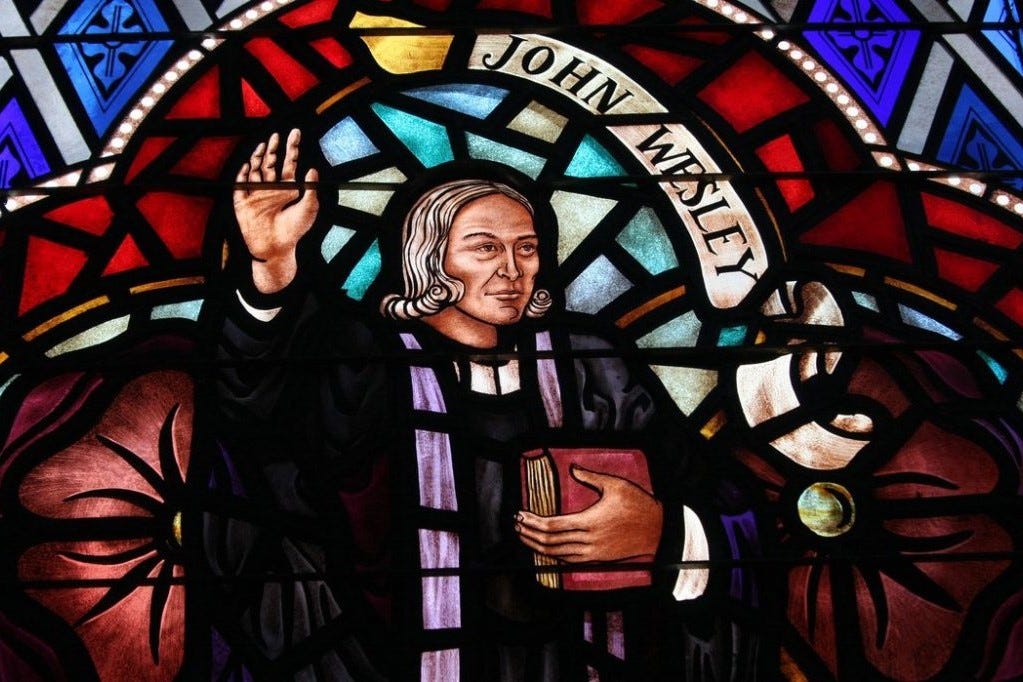

In this post in the EA for Christians community blog, Dominic Roser reflects on John Wesley’s surprisingly EA-aligned views on the use of money. Wesley was an influential Christian preacher in the 1700′s and the founder of Methodism. Wesley suggested a type of earning to give approach, summed up in a slogan “Gain all you can, save all you can, give all you can”.

The original post was published in two parts, but here they are published together. Part 1 contains an abridged form of Wesley’s original sermon in modern English, while Part 2 contains Dominic’s reflections on it.

The EACH community blog is a multi-author and multi-perspective blog. The views presented in the posts are those of the authors and do not represent the views of EA for Christians. Most of the posts in the blog share a Christian point of view.

John Wesley: The Use of Money (Part 1)

My favourite sermon is the 18th century sermon on “The Use of Money” by John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist church. His words are passionate, radical, simple, and practical. Upon reading it again, I even had wet eyes. The core message of Wesley’s sermon is: Earn all you can, Save all you can, Give all you can. This sermon might possibly be the most EA kind of thing that has been written before Peter Singer came along.

The sermon is posted below (in an abridged version). The purpose of this blogpost is simply to put the sermon up for discussion. In case anyone would like to dig deeper: there is an accompanying and somewhat lengthy blog post here which does the work of filtering out how exactly Wesley’s sermon overlaps (or stands in tension with) Effective Altruism. It also quotes some touching facts on how Wesley himself put his words into practice.

“The Use of Money” by John Wesley

(Abridged and put into modern English by Richard Hall. The full-length version is here.)

“I tell you, use worldly wealth to gain friends for yourself, so that when it is gone, you will be welcomed into eternal dwellings.” (Luke 16:9)

The right use of money is of the utmost importance to the Christian, yet it is a subject given too little attention. Wealth has often been regarded by poets and philosophers as a source of evil and yet the fault lies, not with money, but with those who use it. Indeed, money should be regarded as a gift of God for the benefits that it brings in ordering the affairs of civilization and the opportunities it offers for doing good. In the hands of God’s children, money is food for the hungry, clothing for the naked and shelter for the stranger. With money we can care for the widow and the fatherless, defend the oppressed, meet the need of those who are sick or in pain.

It is therefore most urgent that God’s people know how to make use of their money for his glory. All the necessary instructions can be condensed into 3 simple rules:

Gain all you can

Save all you can

Give all you can

Gain all you can

With this first rule, we sound like children of the world, and it is our bounden duty to do this. There are, however, limits to this rule. We should not gain money at the expense of life or health. No sum of money, however large, should induce us to accept employment which would injure our bodies. Neither should we begin (or continue in) any business which deprives us of the food and sleep that we need. We may draw a distinction between businesses which are absolutely unhealthy, such as those that deal directly with dangerous materials, and those employments which would be harmful to those of a weak constitution. If our reason or experience shows that a job is unhealthy for us, then we should leave it as soon as possible even if this means that our income is reduced.

The rule is further limited by the necessity not to undertake any employment which might injure our minds. This includes the pursuit of any trade which is against the law of God or the law of the land. It is just as wrong to defraud the king of taxes as it is to steal from our fellow citizens. There are businesses which might be innocent in themselves but which, at least in England at this time require cheating, lying or other customs which are contrary to good conscience, to provide an adequate income. These, too, we should avoid. There are other trades which many may pursue with complete innocence but which you may not because of some peculiarity of your nature. For example, I am convinced that I could not study mathematics without losing my faith, yet many others pursue a lifetime study in that field without harm. Everyone must judge for themselves and refrain from whatever may harm their mind and soul.

What is true of ourselves is equally true of our neighbour. We should not “gain all we can” by causing injury to another, whether to his trade, his body or his soul. We should not sell our goods below their market price nor should we entice away, or receive, the workers’ that a brother has need of. It is quite wrong to make a living from selling those things which would harm a neighbour’s health and physicians should not deliberately prolong a patient’s illness in order to improve his own income.

With these restrictions, it is every Christian’s duty to observe this first rule: ‘Gain all you can’. Gain all you can by honest work with all diligence. Lose no time in silly diversions and do not put off until tomorrow what may be done today. Do nothing by halves; use all the common sense that God has given you and study continually that you may improve on those who have gone before you. Make the best of all that is in your hands.

Save all you can

This is the second rule. Money is a precious gift. It should not be wasted on trivialities. Do not spend money on luxury foods, but be content with simple things that your body needs. Ornaments too, whether of the body, house or garden are a waste and should be avoided. Do not spend in order to gratify your vanity or to gain the admiration of others. The more you feed your pride in this way, the more it will grow within you.

And why should you spoil your children in this way? Fine clothes and luxury are a snare to them as they are to you. Why would you want to provide them with more pride and vanity? They have enough already! If you have good reason to believe that they would waste your wealth then do not leave it to them. Do not tempt them in this way. I am amazed at those parents who think that they can never leave their children enough. Have they no fear of hell? If there is only one child in the family who knows the value of money and there is a fortune to be inherited, then it is that one who should receive the bulk of it. If no child can be trusted in this way then it is the Christian’s duty to leave them only what will keep them from being in need. The rest should be distributed in order to bring glory to God.

Give all you can

Observing the first two rules is far from enough. Storing away money without using it is to throw it away. You might just as well cast your money into the sea as keep it in the bank. Having gained and saved all you can, then give all you can.

Why is this? You do not own the wealth that you have. It has been entrusted to you for a short while by the God who brought you into being. All belongs to him. Your wealth is to be used for him as a holy sacrifice, made acceptable through Jesus Christ.

If you wish to be a good steward of that which God has given to you on loan the rules are simple enough. First provide sufficient food and clothing for yourself and your household. If there is a surplus after this is done, then use what remains for the good of your Christian brothers and sisters. If there is still a surplus, then do good to all people, as you have the opportunity. If at any time you have a doubt about any particular expenditure, ask yourself honestly:

Will I be acting, not as an owner, but as a steward of the Lord’s goods?

Am I acting in obedience to the word of God?

Is this expense a sacrifice to God through Jesus Christ?

Do I believe that this expense will bring reward at the day of resurrection?

If you are still in doubt, put these questions as statements to God in prayer: “Lord, you see that I am going to spend this money on … and you know that I am acting as your trusted steward according to your design.” If you can make this prayer with a good conscience then you will know that your expense is right and good.

These, then, are the simple rules for the Christian use of money. Gain all you can, without bringing harm to yourself or neighbour. Save all you can by avoiding waste and unnecessary luxuries. Finally, give all you can. Do not limit yourself to a proportion. Do not give God a tenth or even half what he already owns, but give all that is his by using your wealth to preserve yourself and family, the Church of God and the rest of humanity. In this way you will be able to give a good account of your stewardship when the Lord comes with all his saints.

I plead with you in the name of the Lord Jesus, no more delay! Whatever task is before you, do it with all your strength. No more waste or luxury or envy. Use whatever God has loaned to you to do good to your fellow Christians and to all people. Give all that you have, as well as all that you are, to him who did not even withhold his own Son for your sake.

John Wesley: The Use of Money (Part 2)

John Wesley preached an amazing sermon on “The Use of Money”. I posted the sermon here. In it, Wesley anticipates a lot of EA thinking 200 years ahead of time. Even the name of the first EA organization—Giving What We Can—corresponds almost literally to the sermon’s slogan.

In case anyone would like to dig deeper: the below blogpost analyzes the sermon in detail and lists seven points of overlap (or, occasionally, tension) between Wesley and Effective Altruism. At the end of the post, I also add a quote which sheds some light on how Wesley put his words into practice.

1. Money is a great tool

Wesley is very annoyed about all the people who despise money. While he thinks that, unfortunately, money can be loved and used badly, he emphatically denies that this must be the case. To the contrary: Money can do great things. He speaks in glowing terms of its potential:

“In the hands of [God’s] children, [money] is food for the hungry, drink for the thirsty, raiment for the naked: It gives to the traveller and the stranger where to lay his head. By it we may supply the place of an husband to the widow, and of a father to the fatherless. We may be a defence for the oppressed, a means of health to the sick, of ease to them that are in pain; it may be as eyes to the blind, as feet to the lame; yea, a lifter up from the gates of death!”

When he decries luxury, he does so not only because it harms the soul of the rich. But also because luxury costs so much—and the money used for buying luxury goods could be put to better use: “Cut off all this expense! Despise delicacy and variety”.

2. We should earn as much as we can

Wesley doesn’t just think it’s permissible, or good, to earn a lot of money. He says that it is “our bounden duty” to do so.

Interestingly, he qualifies this in a similar way that some EAs qualify it: One shouldn’t harm oneself in earning a lot. For example, one should sleep enough. The advice by 80,000 Hours also stresses that one should find one’s work engaging and one should pay attention to avoid burning out.

However, it must be admitted that while Wesley says that one should not harm oneself by working too hard, some of his advice seems like a sure-thing recipe for burnout: “Every business will afford some employment sufficient for every day and every hour. That wherein you are placed, if you follow it in earnest, will leave you no leisure for silly, unprofitable diversions. You have always something better to do, something that will profit you, more or less.” I have the impression that he is a bit overly puritan here. His radical views against enjoying any leisure might be particularly off the mark in today’s time where the problem often is an over-working culture rather than sloth. (In contrast, his puritan radicalism against luxuries might be even more relevant today than it was in his days).

Wesley also diverges from EA when it comes to the limits on Earning to Give. He places much stricter constraints on the kinds of careers one may pursue than typical EAs do. These constraints are of a very deontological nature: we are not allowed to “do evil that good may come”. He also says: “for to gain money we must not lose our souls”. (One might question, though, whether his injunction against procuring money in harmful ways chimes well with the scripture on which his sermon is based).

3. Aim at the best

While Wesley doesn’t use the expressions “cost-effectiveness” and “maximizing”, his sermon is suffused with the mindset of aiming at the best rather than simply the good. Wesley highlights Jesus’ words: “The children of this world are wiser in their generation than the children of light”. The former “more steadily pursue their end”. And the children of this world more often discuss the right use of money than Christians. Wesley exhorts us to use reason and be diligent in order to improve effectiveness: “You should be continually learning, from the experience of others, or from your own experience, reading, and reflection, to do everything you have to do better to-day than you did yesterday.” We should be shrewd rather than randomly generous: “We ought to gain all we can gain, without buying gold too dear, without paying more for it than it is worth.”

Notice how many times Wesley uses maximizing expressions: He says we should understand how to employ money “to the greatest advantage”. And: “It is therefore of the highest concern that all who fear God know how to employ [money]; that they be instructed how it may answer these glorious ends [such as helping the poor], and in the highest degree.” He says: “Employ whatever God has entrusted you with, in doing good, all possible good, in every possible kind and degree”. We should do our work “as well as possible.”

4. Be radical

Wesley is radical. He speaks out against the simple rule of giving 10%: “‘Render unto God,’ not a tenth, not a third, not half, but all that is God’s, be it more or less”. He is very skeptical of leaving a bequest for one’s children: “And why should you throw away money upon your children … Have pity upon them, and remove out of their way what you may easily foresee would increase their sins”. He uses strong language throughout the sermon. Imagine a preacher using such language today!

His radicalness is accompanied by an awareness of the problem of “demandingness” which also looms large in today’s discussions of EA (i.e. the question whether a radical morality doesn’t crush our spirits by demanding “too much” of us). He even says of himself with regard to his injunctions: “Whether I would do it or no, I know what I ought to do” (in other words, he is aware that he might not live up to his high standards). And at one point, he exclaims: “Hard saying! who can hear it?”

5. Impartiality

EA promotes impartiality between humans here & there, now & later, humans & animals, etc. In contrast, Wesley has a “concentric circle” model for apportioning responsibility: First, we must look after ourselves, then after our household, then after fellow Christians, and lastly after all of humankind. However, this partiality diverges much less from EA than it might seem at first sight. Wesley here only speaks of basic needs: “Things needful for yourself; food to eat, raiment to put on, whatever nature moderately requires for preserving the body in health and strength.” As soon as my own needs are met, it is time for my household’s needs to be met, and as soon as these are met, it is the turn of the needs of the “household of faith”, and as soon as these are met, the needs of all humans must be met. In my view, this prioritization of the near & dear is not repugnant since Wesley does not suggest to give priority to increasing the welfare of the near & dear even beyond their basic needs unless the basic needs of strangers are met first. If we take his ideas seriously, we should first meet the basic needs of the poor in distant countries before considering buying nice clothes for ourselves or our children.

6. Advice on how much to give

In his blogpost [broken link], David Wohlever asked how much of our money we ought to keep and how much we ought to give away. This is a challenging question. Wesley isn’t hesitant and claims that there is an easy way to answer:

“If, then, a doubt should at any time arise in your mind concerning what you are going to expend, either on yourself or any part of your family, you have an easy way to remove it. Calmly and seriously inquire,

“(1.) In expending this, am I acting according to my character? Am I acting herein, not as a proprietor, but as a steward of my Lord’s goods? (2.) Am I doing this in obedience to his Word? In what Scripture does he require me so to do? (3.) Can I offer up this action, this expense, as a sacrifice to God through Jesus Christ? (4.) Have I reason to believe that for this very work I shall have a reward at the resurrection of the just?”

You will seldom need anything more to remove any doubt which arises on this head; but by this four-fold consideration you will receive clear light as to the way wherein you should go.

If any doubt still remain, you may farther examine yourself by prayer according to those heads of inquiry. Try whether you can say to the Searcher of hearts, your conscience not condemning you,

“Lord, thou seest I am going to expend this sum on that food, apparel, furniture. And thou knowest, I act herein with a single eye as a steward of thy goods, expending this portion of them thus in pursuance of the design thou hadst in entrusting me with them. Thou knowest I do this in obedience to the Lord, as thou commandest, and because thou commandest it. Let this, I beseech thee, be an holy sacrifice, acceptable through Jesus Christ! And give me a witness in myself that for this labour of love I shall have a recompense when thou rewardest every man according to his works.”

Now if your conscience bear you witness in the Holy Ghost that this prayer is well-pleasing to God, then have you no reason to doubt but that expense is right and good, and such as will never make you ashamed.”

Thus, he resists giving a one-size-fits-all-principle but rather instructs us to examine our character and the situation in light of certain questions and in prayer.

7. Reasons for giving

How does Wesley argue for our duty to give away money generously? His reasons diverge from standard secular EA reasoning. For one, Wesley says that everything belongs to God: “He placed you here not as a proprietor, but a steward”. A second point is that God himself gave all he had for us: “Give all ye have, as well as all ye are, a spiritual sacrifice to Him who withheld not from you his Son, his only Son”. A third point appears in the (theologically very challenging, I think) scripture on which the sermon is based and also in the closing sentence of the sermon: By giving all you have you are “laying up in store for yourselves a good foundation against the time to come, that ye may attain eternal life!”

Did Wesley put his words into practice?

The topic of money was obviously important to Wesley: He preached at least 27 times on this passage of scripture (Luke 19:9) over the course of 18 years. And he brought up the topic in many other sermons and texts (as is claimed here). But Wesley not only preached but also practised the lifestyle that he advocated. The following account is intriguing:

“While at Oxford, an incident changed [Wesley’s] perspective on money. He had just finished paying for some pictures for his room when one of the chambermaids came to his door. It was a cold winter day, and he noticed that she had nothing to protect her except a thin linen gown. He reached into his pocket to give her some money to buy a coat but found he had too little left. Immediately the thought struck him that the Lord was not pleased with the way he had spent his money. He asked himself, Will thy Master say, “Well done, good and faithful steward”? Thou hast adorned thy walls with the money which might have screened this poor creature from the cold! O justice! O mercy! Are not these pictures the blood of this poor maid?

Perhaps as a result of this incident, in 1731 Wesley began to limit his expenses so that he would have more money to give to the poor. He records that one year his income was 30 pounds and his living expenses 28 pounds, so he had 2 pounds to give away. The next year his income doubled, but he still managed to live on 28 pounds, so he had 32 pounds to give to the poor. In the third year, his income jumped to 90 pounds. Instead of letting his expenses rise with his income, he kept them to 28 pounds and gave away 62 pounds. (...) Even when his income rose into the thousands of pounds sterling, he lived simply, and he quickly gave away his surplus money. One year his income was a little over 1400 pounds. He lived on 30 pounds and gave away nearly 1400 pounds. (…)

[One] way Wesley limited expenses was by identifying with the needy. He had preached that Christians should consider themselves members of the poor, whom God had given them money to aid. So he lived and ate with the poor. Under Wesley’s leadership, the London Methodists had established two homes for widows in the city. They were supported by offerings taken at the band meetings and the Lord’s Supper. In 1748, nine widows, one blind woman, and two children lived there. With them lived John Wesley and any other Methodist preacher who happened to be in town. Wesley rejoiced to eat the same food at the same table, looking forward to the heavenly banquet all Christians will share.”

Executive summary: John Wesley, an 18th century Christian preacher, advocated an “earning to give” approach with radical and EA-aligned views on money, including maximizing income ethically, avoiding unnecessary spending, and donating all surplus to effectively help others.

Key points:

Wesley believed money was a tool for good that should be gained ethically, saved by avoiding excess, and given generously.

He took an earning to give approach, saying to maximize income ethically through hard work while minimizing unnecessary expenses.

Wesley advocated total impartiality in giving after basic needs are met, aiding strangers before indulging oneself and family.

He was very radical, arguing to give away all surplus, not just a percentage, to do the most good.

Wesley instructed assessing spending via questions of stewardship, obedience, sacrifice, and eternal reward.

He lived simply himself, limiting expenses to donate large proportions of his income.

Wesley diverged from EA in stronger limits on careers and giving priority to proximal needs first.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.