StrongMinds (6 of 9): Organisation-specific factors

This is the sixth in SoGive’s nine-post sequence evaluating StrongMinds, authored by Ishaan with substantial input and support from Sanjay and Spencer.

Post 1: Why SoGive is publishing an independent evaluation of StrongMinds

Post 3: What’s the effect size of therapy?

Post 4: Psychotherapy’s impact may be shorter lived than previously estimated

Post 5: Depression’s Moral Weight

This post: StrongMinds: Organisation-specific factors

Executive summary

About StrongMinds: StrongMinds delivers interpersonal group psychotherapy in Uganda and Zambia through a variety of programs including in-person group therapy, teletherapy, and therapy delivered via government and NGO partners.

Our overall view of the StrongMinds team is positive. In our experience it’s rare (possibly unique?) to find a mental health NGO that (a) consistently tracks their results on a before-and-after basis (b) incorporates cost-effectiveness in their monitoring, and (c) puts that information in the public domain.

Our cost adjustments: StrongMinds reports spending around $64 per person treated through all of their programs. After making some subjective judgement calls which attributed 17% of the impact to StrongMind’s partners, we bring this figure up to $72.94 on a total costs basis. This is the main quantitative output of this document.

We recommend restricting funding to low income countries: Most of StrongMinds’ work takes place in low income countries, but not all of it. Using some subjective judgement calls, we estimate that restricted funding might be more cost effective, at $62.56 per person.

We anticipate that StrongMinds costs will continue to lower over time. StrongMinds has an exciting new volunteer based program with costs that may fall under <$15 per person, and a track record of pushing for improvements in cost effectiveness. We think $62.56 and $52.98 are reasonable guesses for where StrongMinds might be next year with unrestricted and restricted funding, respectively.

Our quantification of the organisation-specific elements of our model includes a number of subjective assessments, and several of them could be improved with further work.

StrongMinds Phase I and Phase II pilot data has previously come under criticism. We find that the data can be explained by risk of bias factors and is consistent with what we would expect from a simple “collect data before-and-after treatment” methodology. In our meta-analysis, studies which did not do double blinding, careful randomisation, and intention to treat analysis found similar results as what StrongMinds found in their pilot studies.

We think StrongMinds internal data is useful as a form of monitoring treatment outcomes. We don’t think StrongMinds should be pressured to regularly collect higher quality data that includes double blinding and careful randomization because that would be too expensive. However we prefer to use academic sources with double binding, randomisation, and intention to treat analysis to estimate the true effect size.

Introduction

What is StrongMinds

StrongMinds provides free group interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT-G) to low-income women and adolescents with depression primarily in Uganda and Zambia. There is also work in Kenya, with plans to expand to other countries, including the USA. The therapy is delivered by laypeople who have undergone two weeks of training from a therapist specialising in IPT-G. The practice of training a layperson to perform psychotherapy is called “task shifting”, and it is important for reducing the costs of the intervention. Groups consist of 5-12 people who meet for 90 minutes a week, over six sessions.

StrongMinds has a particularly strong M&E program

The StrongMinds program is modelled off of Bolton (2003), a randomised trial which reported a particularly high effect size, with a follow-up study by Bass (2006). StrongMinds’ has conducted Phase I and Phase II pilot studies and follow up reports as well as continually publishing quarterly updates assessing clients before and after therapy. StrongMinds is the only organisation that we know of in the mental health sphere which internally collects this level of data.

StrongMinds treats both directly and via partners. We attribute some of StrongMinds impact to its partners

StrongMinds treats some beneficiaries directly, but most beneficiaries are treated via programs delivered via government and NGO partners. We think that partner programs are helpful in increasing StrongMind’s total impact and cost effectiveness, leveraging resources that otherwise might not have gone to equally cost-effective interventions (though they may be trickier to monitor and make impact attribution confusing).

We attribute 17% of the total impact to the partners themselves, rather than to actions by StrongMinds. In other words, we model that 17% of StrongMinds current impact via partner programs might have happened without StrongMinds intervention, due to positive actions by the partners themselves. This figure involves many judgement calls and arbitrary guesses. See our section on Estimating Impact of Partner Programs to learn more about how we arrived at this figure.

Attributing some credit to partners drives the cost per person up from $64 to $72.94. This is the main quantitative output of this document, which will be plugged into our overall cost-effectiveness analysis.

We are cautiously optimistic about cost effectiveness improving over time

StrongMinds has an exciting new partner program which may cost as little as $15 per person. StrongMinds has a track record of reducing costs over time and moving resources towards more cost-effective programs and away from less cost-effective ones. The existence of programs which achieve costs <$15 per person suggests that the price has not yet found its floor and that there is room for past trends to continue. On balance, based on our experience of following their work over the years, we are more inclined to believe that costs will continue to decline. After removing the pandemic year, we think the trend suggests a cost reduction of 14% per year. Forecasting this is difficult, but we’re cautiously optimistic about StrongMinds becoming more cost-effective over time.

Donors should investigate options restricting funding to low income countries.

StrongMinds has ambitions to expand further with StrongMinds America and StrongMinds Global, but these programs will be in higher income settings and involve a higher cost per person treated. We think donors considering StrongMinds should restrict funding to cost-effective programs in low-income countries, and be aware of fungibility and displacement concerns. We estimate that restricted funding might be more cost effective, at $59.36 per person, but this figure also involves subjective judgement calls. Despite generally being cost-effectiveness oriented within-country, we don’t think StrongMinds will always reliably choose to prioritise lower-income regions where therapy costs less when given unrestricted funding.

Our quantitative estimates are not resilient

Relative to our work on the effect size and duration of psychotherapy in general, we spent much less time investigating the costs and counterfactuals and fungibility adjustments of StrongMinds specifically. We anticipate that it would be possible to find considerations or information which would change our answers without too much extra work.

We also want to emphasise that these estimates are our own, and involve a lot of guesswork. Because of time constraints, several elements have not been checked by StrongMinds for quality or accuracy. If there were enough donor interest, we believe we would be well-positioned to improve this area of analysis further.

Regarding StrongMinds internal M&E and its accuracy

The StrongMinds Phase I trial reports that the treatment group improved by 5.1 PHQ-9 points over the control group, which would correspond to an effect size of around 1.2. Phase II and StrongMinds Quarterly Report data are in line with this. This data has previously come under some criticism on the EA forum.

In our meta-analysis, What’s the effect size of therapy?, we find that academic studies which do not blind assessors, do not blind patients, do not do rigorous randomisation, and do not apply intention to treat analysis (in other words, studies which do a simple before-and-after measurement) had a pooled Hedges g of 1.2, replicating StrongMind’s results.

This implies that StrongMinds internal data is consistent with what one would expect if you collected basic “before and after treatment” data from intervention and control, without doing the adjustments necessary to discover the “true” figure for what the actual impact of therapy was on the client.

After applying the necessary adjustments, our meta-analysis suggests that the true effect size after therapy would be g = 0.41 equivalent to 1.7 PHQ-9 points, adjusted to 0.32 (or 1.3 PHQ-9 points) for having only six sessions. We think this better reflects the underlying true figure.

StrongMinds seems optimistic that their higher internal figures do reflect a genuinely higher quality of the intervention - we think this a mistake, albeit one that reasonable people could make. We think more scepticism from StrongMinds regarding the validity of their internal data is warranted.

We don’t think StrongMinds should be pressured to collect higher quality data, as full randomisation and double blinding would probably be quite expensive. We think it’s best to use StrongMind’s M&E as an assurance that each patient is receiving therapy and having their before-after progress monitored, and we should estimate the effect size of therapy via academic sources.

Estimating Cost Per Per Person for StrongMinds Uganda and Zambia

StrongMinds aims to achieve $64 per person treated in 2023, and has historically met or exceeded quarterly goals. Based on unreleased documents, we tentatively estimate that 30% of these costs are currently going to expansion-related costs, which includes StrongMinds America but may include expansions to other low and middle income countries. Based on this we estimate that the cost per person after subtracting expansion related costs is $44.80.

Estimating Impact of Partner Programs

StrongMinds has three main types of partner programs:

Volunteer-led programs are often led by people who have received psychotherapy themselves. We are particularly excited about these programs, as the costs for these programs can go under $15 per person.

Programs run by StrongMinds Staff: StrongMinds has a telehealth program in Uganda and an in-person, staff led program in Zambia. We estimate that the average of these programs costs $87 per person (with telehealth being the more expensive of the two, and after removing the portion of the program’s resources allocated to expansion).

Partner programswith the Ugandan government and with Ugandan and Zambian NGOs. StrongMinds helps partners start up their own psychotherapy programs, including but not limited to training, technical assistance, monitoring for quality assurance. Partner programs cost less than programs run by StrongMinds staff, but more than volunteer programs.

Since 2022 the majority of StrongMinds patients are treated by partner programs. Partner programs involve StrongMinds giving 8 weeks of training to another organisation. The use of partner programs has enabled rapid scaling and a reduction in costs—though a majority of patients are treated by partners, only about half the costs seem to be associated with partners.

We want to calculate cost-effectiveness in a way that rewards StrongMind for creating partner programs and leveraging partner contributions, while also acknowledging the impact of the partners and avoiding “double counting”[1] by attributing all of the impact to StrongMinds alone.

We broke down spending into four categories

Impact of programs run directly by StrongMinds staff or volunteers is attributed to StrongMinds

Impact of spending by StrongMinds to support partners is attributed to StrongMinds

The impact of estimated contribution made by partners towards working with StrongMinds are split

Leverage: Some proportion of this contribution would not have been as well spent if not for StrongMinds, and its impact should be attributed to StrongMinds

The remainder should be attributed to the partner, under the assumption that the partner would otherwise have spent these resources well, and should therefore represent an increase in the overall costs of the StrongMinds intervention.

We have no data on partner spending, so we make an estimate. We estimate that it costs StrongMinds around $87 to treat one additional person using staff-led programs, with no partners involved. We model that whenever a partner program costs less than $87 per person, the partner program is effectively “contributing the difference”—for example, if StrongMinds was paying $45 per person for a partner program, we would assume the partner was contributing the other (1-$45)/$87=51% of the value.

Having acknowledged partner contributions, we also want to StrongMinds credit for

influencing the partner to choose to do this program instead of something less effective

enabling the partner to do the program where they otherwise might not have the right skills

improving the efficiency with which the program is run relative to how it would have been otherwise

To quantify this element of StrongMinds counterfactual impact, we need to estimate how cost-effective each partner might have been even without StrongMinds’ involvement. In other words, how well might the resources that the partner is putting towards StrongMinds have been used otherwise?

Happier Lives Institute suggested (McGuire, 2023, p71) reported the following regarding NGOs

Based on a subsample of partner NGOs that we have more information about, 2 out of 5 of them (but representing 60% of NGO cases) appear to have a prior commitment to providing mental health services. This raises the possibility that part of the NGO cases…would have been treated without StrongMinds intervention

Based on this report, we estimated that if StrongMinds hadn’t gotten involved, NGO partners would have been only 75% as cost-effective with the same resources that they invest into their StrongMinds partnership.

Happier Lives Institute suggested (McGuire, 2023, p71) reported the following regarding government programs

We think that the government-affiliated workers (CHWs and teachers) are trained and supported (with technical assistance and a stipend) to deliver psychotherapy on top of their other responsibilities. We don’t think that they would have treated mental health issues, or that this additional work displaces the value of the work they do (p71)… This is especially salient for CHWs who may also provide valuable treatments to diseases such as malaria. But we discussed this with a doctor working in Uganda and they were unconcerned about this as an issue, saying that CHWs tend to have light work loads and that in their experience even busy CHWs rarely work more than half a day (p 71 footnote 92).

Based on this report, we estimated that if StrongMinds hadn’t gotten involved, government partners would be only 50% as cost-effective with the same resources that they invest into their StrongMinds partnership.

After making these estimates, we finally attribute 17% of StrongMind’s total impact to the partners. This brings the total cost per person treated within low income countries up from $44.80 to $53.74. After adding expenditure related to expanding to other countries and StrongMinds America back in, the headline figure rises from $64 to $72.94, which is the main quantitative output of this document.

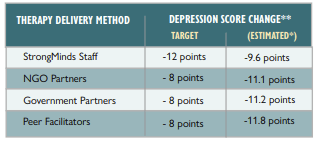

Please note that these charts and figures reflect estimates by SoGive based on fairly limited information and involving many subjective judgement calls, and should not be considered as endorsed or confirmed by StrongMinds.

StrongMinds did provide us with a per-program cost breakdown which we used to make some of our estimates. It is currently confidential, but we will add a link if and when it is released. However, the figures displayed here remain largely reflective of SoGive’s subjective judgements rather than data, and should be treated accordingly with respect to level of scepticism.

Estimating Cost Per Per Person for Restricted Funding

We previously established our estimate that it costs $53.74 to treat people in Uganda and Zambia after including the “counterfactual” social cost to partner programs, and that this rises to $72.94 after including the costs of activities related to expansion, which may include high income countries (such as StrongMinds America) as well as low and middle income countries like Kenya, Ethiopia, and Ghana. We don’t have information about the exact breakdown of expansion related funding, so we insert our own estimates here.

Fungibility adjustments: Because money is fungible, restricted grants can change how organisations choose to allocate unrestricted funding. If we make a subjective guess that 13% of restricted funding will be lost to these displacement effects, restricted funds might have a cost-effectiveness of $61.77.

While StrongMinds does generally focus on cost-effectiveness within countries, we recommend restricted funding to programs in low income countries because we are uncertain as to whether StrongMind’s cost person metrics would be fully impartial with respect to nationality.

Our impression is that StrongMinds doesn’t necessarily promise to prioritise putting unrestricted grants towards StrongMinds Uganda and Zambia rather than StrongMinds America, even though working in the United States would likely cost on the order of $500 per person even at scale (which is very cost-effective within the American context, but not on a global scale). However, these expansions are only recently beginning, and to our knowledge all current patients are being treated within Africa. Future donors should watch as the situation evolves.

Strong track record of successful scaling, and reducing costs at scale

Information about StrongMinds’ most recent costs can be found in their quarterly reports. StrongMinds costs have been going down, in part due to scaling and partner programs, and in part due to shortening the number of sessions and increasing group sizes over time.

2020 − 2021 was a transitional year for StrongMinds. While the ongoing Core programs remained cost-effective, starting new Youth programs temporarily raised costs (e.g. startup costs associated with youth-specific things like setting up parental consent paperwork). The Covid pandemic provided impetus to launch tele-therapy programs, which raised costs as well.

HLI, McGuire (2021) previously collected detailed data on each of StrongMinds program’s costs and features during the 2020-2021 year. The details are summarised in this table, with the higher costs for the new programs marked in red.

| Program Type | Country | 2021 budget | Cost per Person | Group size | Length | Description |

| Core | Uganda | 20.85% | $128.49 | 12-14 | 10-12 weeks | Facilitators have 1 year Columbia U IPT-G certification guided by mental health professionals |

| Core | Zambia | 12.97% | $101.70 | |||

| Youth | Uganda | 14.07% | $197.15 | Core but with adolescent female clients. | ||

| Peer | Uganda | 5.70% | $72.00 | 6-8 | Led by graduates of the “core program” with 6 months of co-facilitator training, saving costs | |

| Tele | Uganda | 23.85% | $248.06 | 5 | 8 weeks | mix of facilitators and peers. Inflated cost due to startup. current costs lower. |

| Tele | Zambia | 7.47% | $439.44 | |||

| Youth Tele | Uganda | 6.94% | $215.64 | |||

| Covid, Refugee & Partner (Peer) | Uganda | 8.15% | $86.35 | Covid program is socially distanced. Refugee program serves displaced people from S Sudan and DRC. Partner programs are when SM trains other orgs to implement intervention. | ||

| Average | 185.82 | |||||

In 2023, the costs of the youth program came down as expected. The teletherapy program has gotten cheaper as well, and the proportion of resources allocated to teletherapy has reduced as well, presumably due to it involving higher costs per person. In their 2023 Q2 report, StrongMinds writes:

The average cost-per-patient for teletherapy was three times higher than any other delivery channel. This is due to the relatively smaller group size required for teletherapy, the need to mobilize via radio ads, and expenses related to teleconferencing. In other words, for every person we mobilize, treat, and evaluate via teletherapy, we can serve three people via in-person therapy. We have therefore decided to pause teletherapy as a StrongMinds offering, reverting the program to our Innovations Lab for further exploration and refinement. With our new financial metrics in place, we can examine other cost drivers and categories of expenses more carefully, comparing them between districts, countries, and delivery channels and sharing best practices between departments. The goal, as ever, is to maximize the impact of each donor dollar invested, ensuring we reach as many depression sufferers as possible

We think this demonstrates StrongMinds’ ability to pivot and scale, as well as a willingness to experiment and shut down programs which are too expensive, and a general alignment with EA priorities regarding cost-effectiveness. which we see as strongly positive.

In a preliminary analysis which is not yet published, some volunteer-led programs fall under $15 per person, suggesting that the potential is there for StrongMinds to become even more cost effective. Volunteer led programs are often run by former clients turned group facilitators, and these can often be much more cost-effective than staff led programs.

StrongMind’s track record of pivoting to the most cost-effective options, the transition away from teletherapy, and the promise of excitingly efficient volunteer led programs makes us feel optimistic that StrongMinds will be able to continue to cut costs in the future.

If we take 2019 and 2023 as representative and exclude the intervening years (which included the covid pandemic) we find that costs have been dropping by 14.23% a year. Therefore we think $62.56 and $52.98 are reasonable guesses for where StrongMinds might be next year with unrestricted and restricted funding, respectively. If we are correct in this, then we would predict that StrongMind’s headline quarterly report by this time next year would report around $55 per person.

How accurate is StrongMind’s M&E?

From choosing to model an intervention off using RCTs with strong results (Bolton (2003) and Bass (2006)), to running Phase I and Phase II pilot studies and follow up reports, to regularly publishing quarterly summary statistics about their costs and average impacts every year, to participating in an upcoming RCT StrongMinds stands out among psychotherapy organisations in producing and being informed by research and analysis.

That being said, the current top post regarding StrongMinds on the EA forum questions the validity of StrongMinds Phase I and Phase II pilot data.

We think that Strong Minds internal results do contain inaccuracy, and that these can be entirely explained by the same methodological issues relating to risk of bias in study design that we outlined previously.

What does StrongMinds M&E say?

In pilot studies, StrongMinds reported PHQ-9 raw scores from people who received treatment as well as from control groups who did not receive treatment.

The StrongMinds Phase I trial reports that the treatment group improved by 5.1 PHQ-9 points over the control group. According to our MetaPsy derived data on PHQ-9 standard deviations, this corresponds to an effect of 5.1 / 4.21 = 1.21 sds. Overall, treated participants are reported to have improved by 11.7 points.

The StrongMinds Phase II trial reports that the treatment group improved by 4.5 PHQ-9 points over the control group, or 1.1 SDs. The treatment group is reported to have improved by 13.1 points.

Most of StrongMind’s quarterly reports report between 6 and 14 points of improvement before and after therapy, matching the Phase I and Phase II trial findings, though results vary (we suspect primarily with number of sessions, though we have not done a careful analysis).

These results can be fully explained by risk of bias factors

In our meta analysis, What’s the effect size of therapy?, we compared how correcting for four risk of bias factors—blinding of assessors, blinding of patients, adequate randomisation, and intention to treat analysis to account for dropout rates—distorted effect sizes. We found that studies which failed to design around these four risk of bias factors had a pooled effect size of hedges g = 1.23.

StrongMinds internal data does not account for these factors, and the results are more or less in line with the level of inflation that we would expect from failing to account for these factors. Among studies that accounted for these factors, the aggregate effect sizes of 0.41. Our guess is that the true impact of StrongMinds is as good as the average RCT—no more, no less.

We therefore guess that the true effect size is 0.32, We derived this by taking the pooled effect size 0.41 and making an adjustment for the fact that StrongMinds currently delivers six therapy sessions (the average RCT study has nine sessions).

Despite bias, we don’t necessarily think StrongMinds needs to run fully randomised double blind trials

Full randomisation and double blinding would probably be quite expensive, and we do not think StrongMinds should be criticised for foregoing them. We think it’s best for evaluators to use StrongMind’s M&E as a form of quality assurance that each patient is receiving therapy and having their before-after progress monitored, and we should estimate the actual effect size of therapy via academic sources.

Awareness of these sources of bias may be decision relevant for when it comes to longitudinal data

StrongMinds uses their internal data to improve the impact and cost-effectiveness of their program. We view this very positively.

The sources of bias described above might not necessarily compromise StrongMind’s ability to compare between programs (since the source of bias might be constant between comparisons), but it may create problems when comparing changes over time, such as when deciding the number of psychotherapy sessions that are necessary.

That said, our attempts, attempts by HLI (McGuire 2023), as well as attempts by Cuijpers (2013) to ascertain impact over time and number of sessions seem to have also run into problems and counterintuitive results—this is generally a difficult and messy area.

We’re sceptical of arguments that StrongMinds is better or worse than the typical RCT.

In our analysis of StrongMinds, we have relied heavily on

the pooled effect size of therapy for all randomised controlled trials which passed four risk of bias tests (blinding of participants, blinding of assessors, adequate randomisation, and intention to treat analysis.)

Spontaneous remission and relapse rates from the academic literature to estimate the time course of therapy.

Our method has throughout involved the assumption that psychotherapy has more or less the same effect regardless of the details of implementation, and that the effect of psychotherapy in high quality randomised trials reflects StrongMind’s implementation.

Therefore, we favoured basing our judgements on “large amounts of broader indirect evidence” about the effectiveness of psychotherapy as a whole, rather than putting much weight on smaller amounts of specific and direct evidence regarding StrongMinds, to make our judgements about the effect size of therapy.

While we think favouring indirect evidence this is a fairly defensible proposition, it is also controversial. We present here some of the arguments to the contrary.

Arguments for StrongMinds having exceptionally good therapeutic effects via direct evidence

We think StrongMinds is unusually cost-effective among mental health interventions primarily because they have succeeded at keeping costs low, rather than because the intervention is more effective than other forms of psychotherapy.

However, during a video call with us, Sean Mayberry cited some factors in support of StrongMinds being exceptionally good, better than the typical RCT, and in support of taking data from StrongMinds’ Phase I and Phase II trials relatively at face value:

That Bolton (2003), an RCT in rural Uganda off of which StrongMinds is modelled, backs up the findings of StrongMind’s Phase I and Phase II trials.

We confirm this as true: Bolton (2003) has an effect size of g = 1.32, implying an improvement equivalent to 5.6 PHQ-9 points, similar to that reported by the StrongMind’s Phase I and Phase II trials

Further, we consider Bolton (2003) a well designed study which does intention-to-treat analysis, has adequate randomisation, and blinding of assessors (but not blinding of the participants, some participants may have known which trial they were in prior to agreeing to enrol.) This passes three out of four Risk of Bias factors that we considered in our meta-analysis.

At 6 month post-treatment follow-up, Bolton (2003) reports that only 11.6% of subjects had depression relative to 54.9% of the controls, which is unusually good.

That group therapy specifically creates social bonds that may not be captured in academic trials.

There is some evidence for this: in Bass (2006) most participants continued to attend informal group meetings on their own initiative after the trial was over, with the 14% who did not do so having similar outcomes whilst the therapy was ongoing but worse outcomes after the therapy ended.

We do not agree with these arguments, although we do think these are reasonable arguments in the context of a complex topic, and that reasonable people might disagree about how much to weigh these different sources of evidence.

As outlined previously, we do think that StrongMinds internal data is inflated by not doing intention-to-treat analysis, inadequate randomization and double blinding.

We think that Bolton (2003) is a well designed study. But when we look at the wide range of effect sizes found in the wider literature, we have the intuition that there is generally a lot of “noise” going on in psychotherapy trials, and we feel more comfortable using the results of a meta-analysis than a single study.

Some additional arguments cited in favour of taking StrongMinds’ internal data at face value include:

That some of their data is collected by third parties, and it corroborates their internal data.

We were unable to confirm or deny this, as the full raw data was not released on our request. However, it doesn’t necessarily address our belief that the results are inflated, as we think the inflation stems from accidental study design flaws which third parties would also be vulnerable to, and not from any self-serving bias in reporting. We therefore don’t think that this materially strengthens the case for the data.

StrongMinds also collects data on nutrition and school attendance, which is also improving, adding robustness to the hypothesis that something real is occurring.

We would generally believe this could be true in principle, though potentially subject to similar types of study design biases. However we were unable to independently confirm or deny this as the full raw data was not released on our request, so we did not include those impacts in our analysis.

Arguments for StrongMinds having below average therapeutic effects via direct evidence

An RCT by Baird and Ozler is complete and awaiting publication. We were unable to acquire a draft of this document. Some tweets by one of the study’s authors have led to speculation on the EA forum that outcomes are likely negative. This is not confirmed, and it is possible that the comment is unrelated.

McGuire (2023, p60) wrote that “the Baird et al. study is reported to have a small effect”. They responded to this by using data from Bolton (2003) and Bass (2006) to make an estimate and then applied a very steep ×5% adjustment to anticipate negative results by Baird and Ozler. This figure was considered to be “StrongMinds-specific evidence”.

McGuire (2023, p60) also estimated the effect of psychotherapy in low and middle income countries, using delivery format (lay person therapist, group format) and number of sessions as moderators.

Finally, McGuire (2023, p60) combined these estimates using a Bayesian model that used the effect of psychotherapy in low and middle income countries with moderators appropriate to StrongMinds as an informed prior, and the ×5% adjusted “direct evidence” figure using Bolton (2003) and Bass (2006) as an update to that prior.

Figure: HLI, McGuire (2023) used a meta-analysis of LMIC psychotherapy studies with various moderators to set an “informed prior” and added a pessimistic update to anticipate negative results from Baird and Ozler

In a comment, Gregory Lewis argued that this didn’t go far enough, and that negative results from Baird and Ozler would suggest that StrongMinds was a weaker option “even among psychotherapy interventions” since “picking one at random which doesn’t have a likely-bad-news RCT imminent seems a better bet”.

(Note: In HLI’s previous analysis, HLI, McGuire (2021), see Table 2, including more direct evidence from StrongMinds, as well as looking at studies with “StrongMinds like traits,” made the intervention look better. Hints that Baird and Ozler would produce pessimistic results were not available at the time.)

We symmetrically give less weight to these arguments for pessimism for the same reason that we give less weight to the arguments for optimism—we think that for this intervention, the ups and downs of specific RCTs are less informative than the aggregated evidence from all psychotherapy RCTs in general.

We favour looking at broader evidence over individual RCTs, and strongly emphasise the importance of reducing risk of bias in study design..

Our overall stance on these debates is

Accounting for Risk of Bias in Study Design is very central to our estimate

We can’t rely on StrongMind’s direct evidence because of risk of bias in study design

Differences between HLI’s meta-analysis and ours are explained by not accounting for risk of bias in study design

For any given trial, differences in how risk of bias is accounted for can easily contribute more to their headline reported result than the true effect.

We think broad and high quality evidence from many contexts is better than a small number of RCTs which share many factors with the intervention, or a single RCT on site.

Our intuition is that it’s easy for two RCTs measuring the same underlying thing to give wildly different results, and therefore using a broader evidence base is better

Bolton (2003) and Bass (2006) are well designed, but even well designed RCTs do vary wildly in effect size, not to mention that the intervention in question was chosen because the RCT results had a high effect size, so we should anticipate some regression to the mean

We hesitate to update very negatively on Baird and Ozler (under the scenario where the results are pessimistic) for many of the same reasons we hesitated to update too positively on Bolton (2003) and Bass (2006). We are aiming for a robust estimate, and we think over-updating on individual RCTs will lead to a bit of a random walk rather than an accurate estimate of the true impact.

We favour broader meta-analyses over meta-analyses that are trying to tackle specific reference classes.

Unlike HLI, we did not restrict our meta-analysis to the reference class of low and middle income countries (though it happens to be the case that after risk of bias filtering, it wouldn’t have made any difference if we had) because that would reduce the number of studies available which passed all of our risk of bias criteria

Unlike HLI, we did not incorporate our moderator analysis into our final estimates. E.g. We don’t add an adjustment for lay-counsellor vs trained therapist, or for individual vs group care, because we don’t think there’s enough evidence that these factors make a big difference, and we don’t think meta-regressions can robustly identify the differences that may be there. (Consider, for example, the failure of meta-regressions to identify the impact of number of therapy sessions, a finding which goes against common sense)

These three stances interact with each other—for example, using a single RCT or a very small number of RCTs often means making compromises with respect to the number of studies that pass all risk of bias criteria. We would consider weighing a single RCT with an optimistic finding more strongly if it were to pass all four aforementioned Risk of Bias assessments, but Bolton (2003) only passes three. An RCT which gave a very pessimistic answer would decrease our confidence in StrongMinds would only drop by a small amount, not a large amount

Figure: Effect sizes vs standard error colour coded by risk of bias in study design, with a visually apparent trend towards fewer criteria passed showing higher effect sizes. Risk of bias is an example of a factor which has nothing to do with the underlying phenomenon being measured, yet creates variation in the data. There is a very large amount of variation even after accounting for risk of bias, much of it over unrealistic ranges. The variation is caused by factors that are not well understood by us, and we haven’t seen anything to suggest that it really corresponds to variation in the underlying thing being measured, leading us to favour pooled estimates. Recall that our review discovered that factors such as therapist experience and therapy type, which we might have hoped would explain this variation, made very little difference.

For these reasons, we tend to reject both optimistic and pessimistic interpretations of direct evidence in favour of our broader estimate of the effects of psychotherapy. We rely on our academic estimates of effect size and duration to quantify the effect size of therapy. Our analysis of StrongMinds itself therefore focuses mostly on the basics outlined in the previous sections: did some form of psychotherapy get delivered, to how many people, and at what cost?

Citations

Resources from StrongMinds

StrongMinds phase 1 and phase 2 and followup evaluations

Follow Up Evaluations for Phase 1 & Phase 2

StrongMinds quarterly updates

https://strongminds.org/quarterly-reports/

StrongMinds General Media

Frontpage—https://strongminds.org/

StrongMinds America—https://www.strongmindsamerica.org/

YouTube—https://www.youtube.com/c/StrongMinds

Twitter—https://www.strongmindsamerica.org/

LinkedIn—https://www.linkedin.com/company/makestrongminds

Facebook—https://www.facebook.com/MakeStrongMinds/

RCTs pertaining to StrongMinds

StrongMinds upcoming RCT pre registration

Negative comments from study author on twitter causing people to anticipate negative results: Özler, B [@BerkOzler12] (2022, Nov 24). No good evidence that Strong Minds is effective [Tweet] X. https://twitter.com/BerkOzler12/status/1595942739027582977

See also EA forum comment and discussion of tweet https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/ffmbLCzJctLac3rDu/strongminds-should-not-be-a-top-rated-charity-yet?commentId=Agn8cLJd4bTTXJFu9

Bolton (2003) RCT and Bass (2006) followup off of which StrongMinds is based

Other citations

HLI 2023 updated analysis

HLI’s estimate of psychotherapy interventions

McGuire, (2021a) “Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Group or task-shifted psychotherapy to treat depression”, Happier Lives Institute

HLI’s estimate of StrongMinds

McGuire, J. (2021b) “Cost Effectiveness Analysis—Strongminds”, Happier Lives Institute

Number of sessions and effect size

- ^

“Double counting” is an error caused by attributing all impact to a lone actor when multiple actors are involved. If someone benefits from a StrongMinds partner program, donations to both StrongMinds and to the partner were involved in creating that result—attributing all of the impact to either party would result in an inflated cost-effectiveness estimate.

Executive summary: SoGive estimates that StrongMinds, a charity providing group psychotherapy in Africa, treats depression for $72.94 per person, after making subjective adjustments for partner contributions and expansion costs. Restricted funding focused on low-income countries may increase cost-effectiveness.

Key points:

StrongMinds has an unusually strong monitoring and evaluation program for a mental health NGO, tracking before-and-after results and cost-effectiveness.

SoGive attributes 17% of impact to StrongMinds’ partners, adjusting the cost per person treated from $64 to $72.94. This estimate involves many subjective judgment calls.

Restricting funding to low-income countries like Uganda and Zambia may increase cost-effectiveness to $62.56 per person, but this is uncertain.

StrongMinds’ internal M&E data is likely biased and inflated compared to the true effect, but is still useful for basic monitoring. Effect sizes should be estimated from academic studies.

StrongMinds has a good track record of increasing cost-effectiveness over time. Costs may continue to decline by around 14% per year.

SoGive favors relying on broad, high-quality meta-analyses rather than individual studies to estimate the true effect size of StrongMinds’ intervention.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Are these cost-savings due to not paying for labour, or because the staff are cheaper to train due to personal experience, or something else?

That’s an interesting question and i don’t know! I had myself implicitly been assuming it was from volunteer labor being unpaid for. But now that you put the question to me explicitly I realize that it could easily be due other factors (such as fewer expenses in some other category such as infrastructure, or salaries per staff, hypothetically). I don’t think the answer to this question would change anything about our calculations, but if we happen to find out I’ll let you know.

In an earlier draft I was considering counting the volunteer labor as a cost equal to the size of the benefits from the cash that the volunteer might have earned otherwise, but I left it off because it would have been too small of an effect to make a notable difference.

Yeah, I was asking w/r/t that counterfactual cost of labour. Perhaps this is a dumb question, but if that cost would’ve been negligible, as you say, then what explains the gap? Is the counterfactual cost of volunteer labour really that much smaller than staff labour?

If you’re interested in the question of why I figure that doing voluntary unpaid labor for most people involves negligible harm or opportunity cost of the type that ought to change our effectiveness estimate, my napkin calculation goes something like: suppose I personally were to replace half my compensated work hours with volunteering. That would be several tens of thousands of dollars of value to me and would half my income, which would be a hardship to me. But it should only take ~$285.92 to “offset” that harm to me personally, by doubling someone else’s income—theoretically the harm i experience for losing one day’s labor can be fully offset by giving a givedirectly recipient 0.78 cents. Obviously my own labor is worth more than 0.78 cents a day on the market, but matters being how they are, 0.78 cents seems to be around what it takes to “offset” the humanitarian cost to me personally (and the same to any volunteer, with respect to them-personally) of losing a day’s labor.

Having established that, how much unpaid labor are we talking about?

Assuming 8 hours of capacity-to-work per day, a volunteer does 5.6-13.5 days of labor per client treated. 1.5 hours × 6 sessions × (5 to 12 people) / 8 hour workday = 5.6-13.5 days of labor per client treated

So if we imagine that volunteers are actually missing work opportunities and sacrificing income in order to do this, $4.37-$10.53 donation to GiveDirectly per client treated might represent the cost to “offset” these potential “harms”. But hopefully volunteers aren’t actually choosing to forgo vital economic opportunities and taking on hardship in order to take on volunteer labor, and are doing it because they like it and want to and get something out of it, so maybe the true opportunity cost/disvalue to them is <20% of the equivalent labor-hours, if not zero?

anyway, this all seems kind of esoteric and theoretical—just something i had considered adding to the analysis (because at first I had an intuition, perhaps one which you had as well to motivate your question, that volunteer labor isn’t really free, just because it is unpaid), and then discarded because it seemed like the effect would be too negligible to be worth the complications it added. Like i said in the other comment, all of that is quite different from the other matter of what it might cost to pay a staff member or volunteer—staff and volunteers presumably have more earning potential as givedirectly recipients who are selected to be low income, and might be able command salaries much higher than that. And I don’t, actually, know the answer with respect to what the program might cost if all volunteers were instead paid, or exactly to what extent main costs are actually about the labor of people directly playing therapist roles (total staff salaries vs other costs might be easier to grab, but that’s answering a different quesiton than you asked, staff infrastructure won’t be all about leading therapy sessions).

To clarify, when i said it “would have been negligible” what I meant more precisely is that “doing voluntary unpaid labor does negligible harm (and probably actually confers benefits) to the volunteer, so I didn’t factor it into the cost estimate”. This is very different from the question of “how much would the cost change if the volunteers were to be paid”—which is a question that I do not know the answer to.