“The Physicists”: A play about extinction and the responsibility of scientists

Abstract

This text is a short summary of Friedrich Dürrenmatts play “Die Physiker” (“The Physicists”). The play is about the moral responsibility of physicists, especially ones capable of developing (something like) the nuclear bomb. It was written in 1960 and contains some interesting perspectives on foundational research and X-Risk). Friedrich tries to illustrate the absurdity of the situation scientists in dangerous fields find themselves in by setting the play in a mental hospital. The plot is basically: A physicist figured out “the theory of everything” and “the system of all possible inventions” and thinks this is extremely dangerous. He tries to “retract” his findings as a result of this. The play is only about 90 pages long and there’s an English translation available. For those who can’t/don’t want to read the book; here is a short (but hopefully still somewhat entertaining) summary and a list of quotes I think are interesting.

Summary

Act

A body is found in the Asylum “Les Cerisiers”, a luxurious facility for the mentally ill, located in the idyllic Swiss countryside. In this particular block of the asylum, the three patients Newton, Einstein, and Möbius are treated. Inspector Voß comes to the sanatorium to clarify the circumstances of the death of the nurse Irene Straub, who was apparently strangled by her patient Einstein.

Three months earlier, Newton had also killed his nurse Dorothea Moser in a similar way. Then, too, the inspector could not arrest the murderer because of his feigned madness.

When Voß wants to make it clear to the head of the Asylum, Dr. Fräulein von Zahnd, that security measures are urgently needed after the second murder of a nurse, she suggests to the inspector that the murders of the nurses are a result of the deformation of the brains by radioactivity. However, since the third inmate had not come into contact with radioactivity, he posed no danger.

The nurse Monika Stettler confesses her love to Möbius: she believes in him and in King Solomon, who—he says - appears to him. At first, he tries to talk her out of her feelings, as he cannot risk making contact with the outside world. But when she is not deterred and proposes to marry him and start a family, Möbius strangles his lover with a curtain cord.

2. Act

The first two scenes of the second act repeat the examination scenes of the first act, but with “reversed circumstances”: The external action largely matches that of the first act, but the opinions and dialogue are mirrored. - The dead nurses have meanwhile been replaced by burly male nurses, all masters of martial arts.

The inspector, once again appearing for questioning, has accepted the (Dis-)order of the asylum and even corrects Dr. von Zahnd: While she speaks of Möbius as a “murderer”, the inspector speaks only of a “perpetrator”. She pretends to be confused surprised by Möbius’ crime. He rejects the obligation to investigate and capitulates to a situation he cannot change anyway.

Möbius talks his way out of any charges by referring to King Solomon, who not only helped him achieve his genius, but also appeared to him to instruct him to murder. Fräulein von Zahnd honestly believes him—a sign of her own madness becoming more and more obvious.

The three physicists admit to their fellow inmates that they are not in fact, crazy. Newton’s real name is Alec Jasper Kilton, he is the founder of the “theory of correspondence”, has signed on as an agent (presumably with the CIA) and represents the capitalist Western bloc. Similarly Einstein, whose real name is Joseph Eisler, discovered the “Eisler effect” and stands for the communist Eastern Bloc. Both are after the work of Möbius, who believes he has discovered “the system of all possible inventions”[1] and the so-called “world formula” and is trying to protect it by having himself committed as a lunatic. Each of the two agents wants to spy on Möbius’ research results for his country. Both draw their pistols, but realize the futility of a duel, as both are equally likely to get shot.

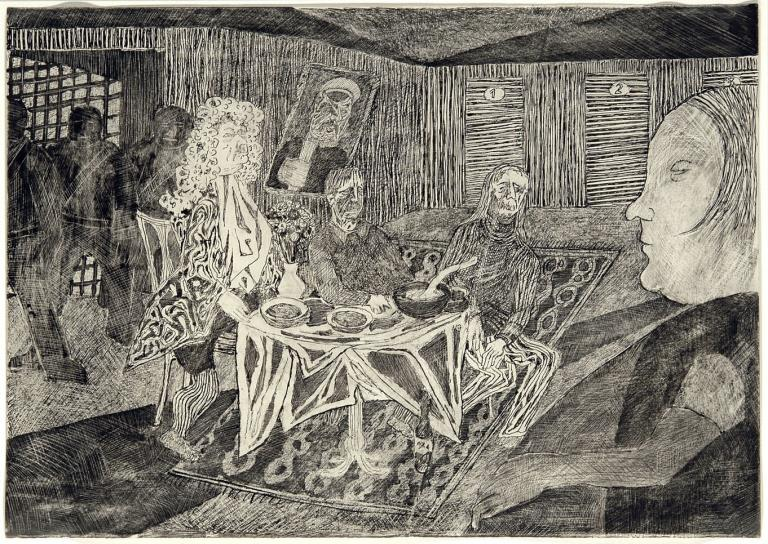

Over dinner, the three physicists discuss the potential end of the world, the moral responsibility of people who discover potentially dangerous truths and invent powerful weapons. There is this really nice portrait of the absurdity of a situation that frequently occurs in EA settings. One second, you ask about how the end of the world is most likely to happen and how we could make it less likely, and the next second you ask someone to pass the salt.

Einstein reminds Möbius of his duty as a scientist to hand over his discoveries to mankind, admits to having no real influence on his political clients and demands the choice of a political system instead of neutrality. Einstein cannot guarantee the use of the scientific results and shifts the responsibility to the party.

Newton demands that, as a genius, one must give away one’s knowledge, which is public property, to “non-geniuses”, assures that the freedom of physics should be preserved, lures with the Nobel Prize and declares that scientists themselves are not responsible for the use of their findings. He rejects any responsibility and shifts it onto the general public.

Möbius exposes apparent possibilities of a free decision as a dead end, fears that Kilton’s (Newton) and Eisler’s (Einstein) paths can only lead to disaster and wants to prevent the risk of the downfall of mankind. He then demands the retraction of scientific knowledge.

When Möbius reveals that he has already burned his notes, the agents realize that their rivalry, which flares up again, has become pointless. Möbius first tries to convince the two of the necessity of remaining in the lunatic asylum on moral grounds: science has become terrible, research dangerous– their findings deadly. He sees the only remaining option as capitulation to reality and the restraint of his findings. This persuasion does not work on the agents and they still want to leave the clinic. Möbius therefore reminds them of their murders: if his knowledge were to become public, the murders would have been in vain and the killings for the protection of humanity would become ordinary murders—and they, as perpetrators, ordinary murderers. He is able to convince them to see their imprisonment as atonement for the murders they have committed and thus to make their contribution to saving humanity. The outcome of the play therefore initially seems positive: the heroes sacrifice themselves, personal guilt is atoned for, the disturbed world order seems restored.

Dr. von Zahnd has the physicists brought from their rooms and disarms the two agents. She tells them that King Solomon has also been appearing to her for years and that she had deliberately set her nurses on the three physicists so that they would die. This tied the physicists to the asylum as “perpetrators”, since outside they would be considered “murderers”. Dr. von Zahnd informs the three that she had already copied all of Möbius’ manuscripts before they were destroyed and kept them for herself. While the three physicists remain locked up in the asylum as supposedly insane, the asylum director will unscrupulously profit from the records without considering what great dangers lie in the new technologies—technologies that could destroy all of humanity. The dramaturgically necessary “worst possible turn” mentioned by Dürrenmatt (the author) in his “21 Points” has occurred.

The 21. Points concerning “the physicists” are listed in the epilogue of the play.

I do not start from a thesis, but from a story.

If one starts from a story, it must be thought through to the end.

A story is finished when it has taken its worst possible turn.

The worst possible turn cannot be foreseen. It occurs by chance.

The art of the dramatist is to use chance as effectively as possible in a plot.

The bearers of a dramatic plot are human beings.

Chance in a dramatic action consists of when and where who happens to meet whom.

The more planned people are, the more effectively chance can affect them.

People who act according to plan want to achieve a certain goal. Chance always hits them the worst when it causes them to achieve the opposite of their goal: That which they feared, that which they tried to avoid (e.g. Oedipus).

Such a story is grotesque, but not senseless.

It is paradoxical.

Just like the logicians, the dramatists cannot avoid paradox.

Just as logicians cannot avoid paradox, neither can physicists.

A drama about physicists must be paradoxical.

It cannot aim at the content of physics, but only at its effects.

The content of physics concerns the physicists, the effects all people.

What concerns everyone can only be solved by everyone.

Any attempt by an individual to solve for himself what concerns everyone must fail.

Reality appears in the paradox.

Those who confront the paradox expose themselves to reality.

Drama can trick the spectator into exposing himself to reality but not force him to withstand it or even overwhelm it.

What would Dürrenmatt say about X-Risk prevention?

If you would go up to Friedrich Dürrenmatt and say: “Okay Friedrich, your story is nice and all, but it doesn’t actually tell us anything about how to handle X-Risk, the threat of a nuclear war, the safe development of AI or S-Risk.” He would probably disagree. Friedrich was convinced of the “unpredictability” of the worst possible turn of events ( → Point 4). But that doesn’t mean that he didn’t have any opinions on how to best handle the threat of human extinction.

He seems to have been both very naive and very pessimistic about how the world would handle the responsibility of knowing something like a unified field theory or the “system of all possible inventions.” Naive because he assumed that the genius at the center of this story , Möbius, is motivated and willing enough to destroy his own credibility for the sake of saving the world from whatever knowledge he produced . (And could actually convince other physicists, his fellow inmates, of doing the same.) Pessimistic, because he doesn’t really seem to see any upsides of knowing this “theory of everything”. He doesn’t seem to think of the opportunities scientific progress could bring. Which, in the 1960’s—the age of technological progress being weaponized to an absurd degree (both for demonstrative and actual “winning”) - is maybe kind of understandable.

The most relevant opinion Dürrenmatt seems to illustrate seems to be a connection between scientific freedom and existential security.

Möbius doesn’t want to join the American, nor the Soviet agent because of their answer to the question, “are your physicists free?” As soon as Kilton or Eisler mention that physicists work for the defense of their countries, Möbius shrugs and says “so they’re not free.” ..implying that science is doomed to become destructive as soon as militaristic agents are institutionally connected to it. Or maybe less controversially: When scientists have to work for the defense of their countries, they have problems they wouldn’t have in other circumstances: They might be pressured to invent things specifically to induce suffering in others or destroying civilization (s))

Some quotes to think about

Möbius: (...) I am content with my fate”.

Newton: But I am not satisfied with it, a rather decisive circumstance, don’t you think? I honor your personal feelings, but you are a genius and as such public property. You are pushing into new areas of physics, but you have not leased science. You have the duty to open the door to us, the non-geniuses.

...

Möbius: Aren’t we going to eat any more?

Newton: I’ve lost my appetite.

Einstein: Too bad about the cordon bleu.

….

Möbius stands up: We are three physicists. The decision we have to make is a decision among physicists. We must proceed scientifically. We must not let ourselves be determined by opinions, but by logical conclusions. We must try to find what is reasonable. We must not make a mistake in thinking, because a wrong conclusion would have to lead to catastrophe. The starting point is clear. All three of us have the same goal in mind, but our tactics are different. The goal is the progress of physics. You, Kilton, want to preserve its freedom and deny it responsibility. You, on the other hand, Eisler, commit physics in the name of the responsibility of the power politics of a certain country. But what does reality look like? I demand information about that, shall I decide. (...) Strange. Everyone offers me a different theory, but the reality they offer me is the same: a prison. I prefer my madhouse. At least it gives me the security of not being exploited by politicians.

Einstein: But after all is said and done, you have to take certain risks.

Möbius: There are risks you must never take: the downfall of mankind is one of them.

..

Newton: Möbius! You can’t ask us to be eternally-.

Möbius: My only chance to remain undiscovered after all. Only in the madhouse are we still free. Only in the madhouse may we still think. In freedom our thoughts are explosives.

Thanks to Michel Justen and Nikola Jurkovich for comments on the draft and my lectures for being boring enough so I can go down random rabbit holes.

- ^

P.S. The System of “All possible inventions”

As I was rereading this book, something struck me as weird. This “System of all possible inventions” seemed less clear than the “world formula” (which I guess we would interpret as some sort of unified field theory.) I couldn’t think of how Dürrenmatt would come across this, or what exactly he would even mean by such a “system”. Simultaneously, I spent some time researching this guy, Fritz Zwicky, a Swiss Phycisist. He invented the “Zwicky Box” or “Morphological Analysis”. He often talked about it as a way to come up with new inventions and gives it credit for his groundbreaking work on jet propulsion (He held some four dozen patents related to jets and thrust, and is sometimes described as the father of the jet engine. He also conducted respected research in crystals, gaseous ionization, the physics of solid state, slow electrons, and thermodynamics. Also, he came up with the concept and name of “dark matter”, neutron stars and a bunch of other cool stuff). Part of what Zwicky thought was so cool about his analysis was that it didn’t only allow for finding some solutions to a problem, but all possible practical solutions, to a problem.

…It turns out Friedrich Dürrenmatt, the author of this play, was a close friend of Zwickys, had lunch with him whenever Dürrenmatt was in the U.S., talked to him about nuclear weapons and morphological analysis. (Zwicky had been one of the first american scientists to visit Hiroshima after the detonation.) (I recommend this biography: Müller, Roland: Fritz Zwicky: Leben und Werk des grossen Schweizer Astrophysikers, Raketenforschers und Morphologen. Glarus,1987.)

This is my favourite drama. In my interpretation it’s more about AI risk (the last idea we need, the invention of all inventions), but Durrenmatt was limited by the technology of his age. I mean, if you think Solomon is the AI character, then the end of the play is about Solomon excaping the “box” while trapping their creators inside.