Acausal normalcy

This post is also available on LessWrong.

Summary: Having thought a bunch about acausal trade — and proven some theorems relevant to its feasibility — I believe there do not exist powerful information hazards about it that stand up to clear and circumspect reasoning about the topic. I say this to be comforting rather than dismissive; if it sounds dismissive, I apologize.

With that said, I have four aims in writing this post:

Dispelling myths. There are some ill-conceived myths about acausal trade that I aim to dispel with this post. Alternatively, I will argue for something I’ll call acausal normalcy as a more dominant decision-relevant consideration than one-on-one acausal trades.

Highlighting normalcy. I’ll provide some arguments that acausal normalcy is more similar to human normalcy than any particular acausal trade is to human trade, such that the topic of acausal normalcy is — conveniently — also less culturally destabilizing than (erroneous) preoccupations with 1:1 acausal trades.

Affirming AI safety as a straightforward priority. I’ll argue that for most real-world-prevalent perspectives on AI alignment, safety, and existential safety, acausal considerations are not particularly dominant, except insofar as they push a bit further towards certain broadly agreeable human values applicable in the normal-everyday-human-world, such as nonviolence, cooperation, diversity, honesty, integrity, charity, and mercy. In particular, I do not think acausal normalcy provides a solution to existential safety, nor does it undermine the importance of existential safety in some surprising way.

Affirming normal human kindness. I also think reflecting on acausal normalcy can lead to increased appreciation for normal notions of human kindness, which could lead us all to treat each other a bit better. This is something I wholeheartedly endorse.

Caveat 1: I don’t consider myself an expert on moral philosophy, and have not read many of the vast tomes of reflection upon it. Despite this, I think this post has something to contribute to moral philosophy, deriving from some math-facts that I’ve learned and thought about over the years, which are fairly unique to the 21st century.

Caveat 2: I’ve been told by a few people that thinking about acausal trade has been a mental health hazard for people they know. I now believe that effect has stemmed more from how the topic has been framed (poorly) than from ground-truth facts about how circumspect acausal considerations actually play out. In particular over-focussing on worst-case trades, rather than on what trades are healthy or normal to make, is not a good way to make good trades.

Introduction

Many sci-fi-like stories about acausal trade invoke simulation as a key mechanism.

The usual set-up — which I will refute — goes like this. Imagine that a sufficiently advanced human civilization (A) could simulate a hypothetical civilization of other beings (B), who might in turn be simulating humanity (B(A)) simulating them (A(B(A)) simulating humanity (B(A(B(A)))), and so on. Through these nested simulations, A and B can engage in discourse and reach some kind of agreement about what to do with their local causal environments. For instance, if A values what it considers “animal welfare” and B values what it considers “beautiful paperclips”, then A can make some beautiful paperclips in exchange for B making some animals living happy lives.

An important idea here is that A and B might have something of value to offer each other, despite the absence of a (physically) causal communication channel. While agreeing with that idea, there are three key points I want to make that this standard story is missing:

1. Simulations are not the most efficient way for A and B to reach their agreement. Rather, writing out arguments or formal proofs about each other is much more computationally efficient, because nested arguments naturally avoid stack overflows in a way that nested simulations do not. In short, each of A and B can write out an argument about each other that self-validates without an infinite recursion. There are several ways to do this, such as using Löb’s Theorem-like constructions (as in this 2019 JSL paper), or even more simply and efficiently using Payor’s Lemma (as in this 2023 LessWrong post).

2. One-on-one trades are not the most efficient way to engage with the acausal economy. Instead, it’s better to assess what the “acausal economy” overall would value, and produce that, so that many other counterparty civilizations will reward us simultaneously. Paperclips are intuitively a silly thing to value, and I will argue below that there are concepts about as simple as paperclips that are much more universally attended to as values.

3. Acausal society is more than the acausal economy. Even point (2) isn’t quite optimal, because we as a civilization get to take part in the decision of what the acausal economy as a whole values or tolerates. This can include agreements on norms to avoid externalities — which are just as simple to write down as trades — and there are some norms we might want to advocate for by refusing to engage in certain kinds of trade (embargoes). In other words, there is an acausal society of civilizations, each of which gets to cast some kind of vote or influence over what the whole acausal society chooses to value.

This brings us to the topic of the present post: acausal normalcy, or perhaps, acausal normativity. The two are cyclically related: what’s normal (common) creates a Schelling point for what’s normative (agreed upon as desirable), and conversely. Later, I’ll argue that acausal normativity yields a lot of norms that are fairly normal for humans in the sense of being commonly endorsed, which is why I titled this post “acausal normalcy”.

A new story to think about: moral philosophy

Instead of fixating on trade with a particular counterparty B — who might end up treating us quite badly like in stories of the so-called “basilisk” — we should begin the process of trying to write down an argument about what is broadly agreeably desirable in acausal society.

As far as I can tell, humanity has been very-approximately doing this for a long time already, and calling it moral philosophy. This isn’t to say that all moral philosophy is a good approach to acausal normativity, nor that many moral philosophers would accept acausal normativity as a framing on the questions they are trying to answer (although some might). I’m merely saying that among humanity’s collective endeavors thus far, moral philosophy — and to some extent, theology — is what most closely resembles the process of writing down an argument that self-validates on the topic of what {{beings reflecting on what beings are supposed to do}} are supposed to do.

This may sound a bit recursive and thereby circular or at the very least convoluted, but it needn’t be. In Payor’s Lemma — which I would encourage everyone to try to understand at some point — the condition ☐(☐x → x) → x unrolls in only 6 lines of logic to yield x. In exactly the same way, the following types of reasoning can all ground out without an infinite regress:

reflecting on {reflecting on whether x should be a norm, and if it checks out, supporting x} and if that checks out, supporting x as a norm

reflecting on {reflecting on whether to obey norm x, and if that checks out, obeying norm x} and if that checks out, obeying norm x

I claim the above two points are (again, very-approximately) what moral philosophers and applied ethicists are doing most of the time. Moreover, to the extent that these reflections have made their way into existing patterns of human behavior, many normal human values are probably instances of the above.

(There’s a question of whether acausal norms should be treated as “terminal” values or “instrumental” values, but I’d like to side-step that here. Evolution and discourse can both turn instrumental values into terminal values over time, and conversely. So for any particularly popular acausal norm, probably some beings uphold it for instrumental reasons while others uphold it has a terminal value.)

Which human values are most likely to be acausally normal?

A complete answer is beyond this post, and frankly beyond me. However, as a start I will say that values to do with respecting boundaries are probably pretty normal from the perspective of acausal society. By boundaries, I just mean the approximate causal separation of regions in some kind o physical space (e.g., spacetime) or abstract space (e.g., cyberspace). Here are some examples from my «Boundaries» Sequence:

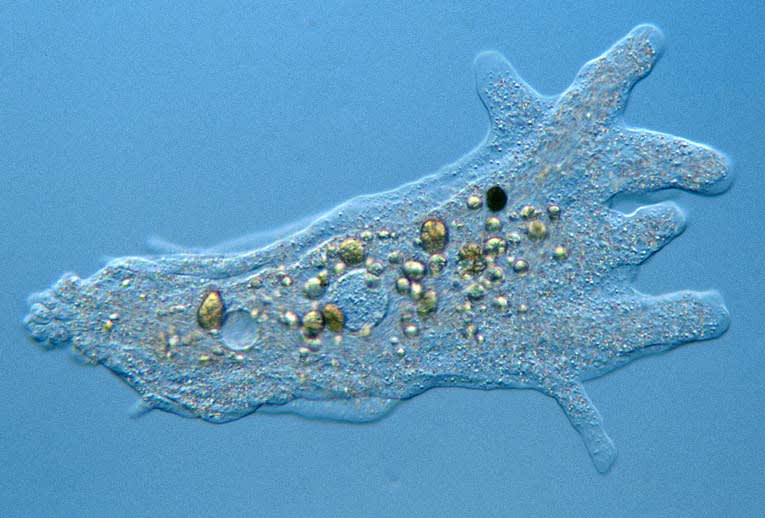

a cell membrane (separates the inside of a cell from the outside);

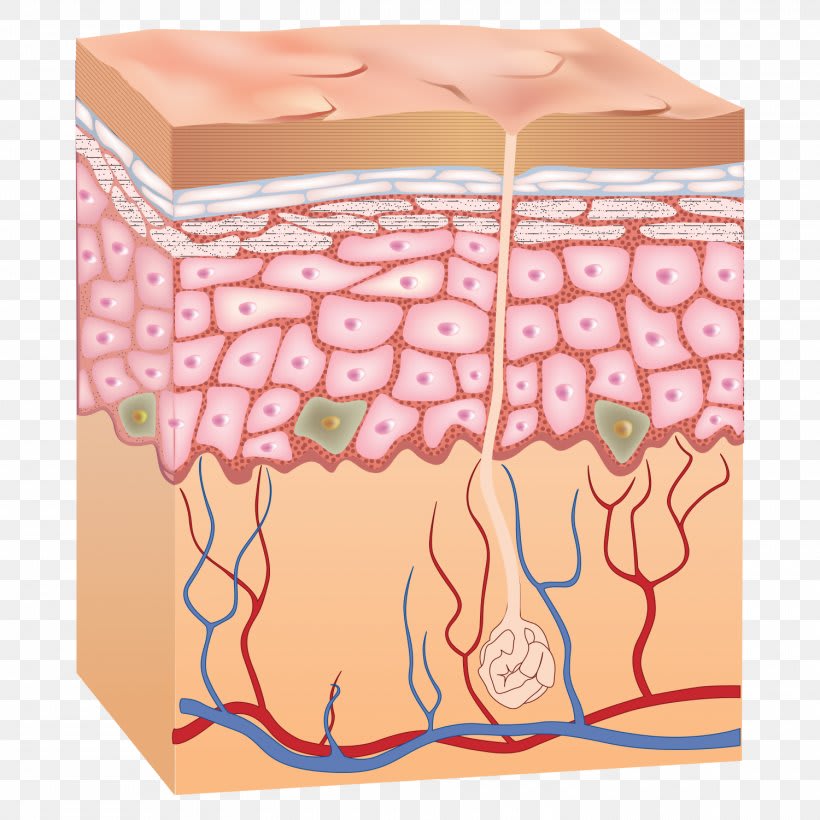

a person’s skin (separates the inside of their body from the outside);

a fence around a family’s yard (separates the family’s place of living-together from neighbors and others);

a digital firewall around a local area network (separates the LAN and its users from the rest of the internet);

a sustained disassociation of social groups (separates the two groups from each other)

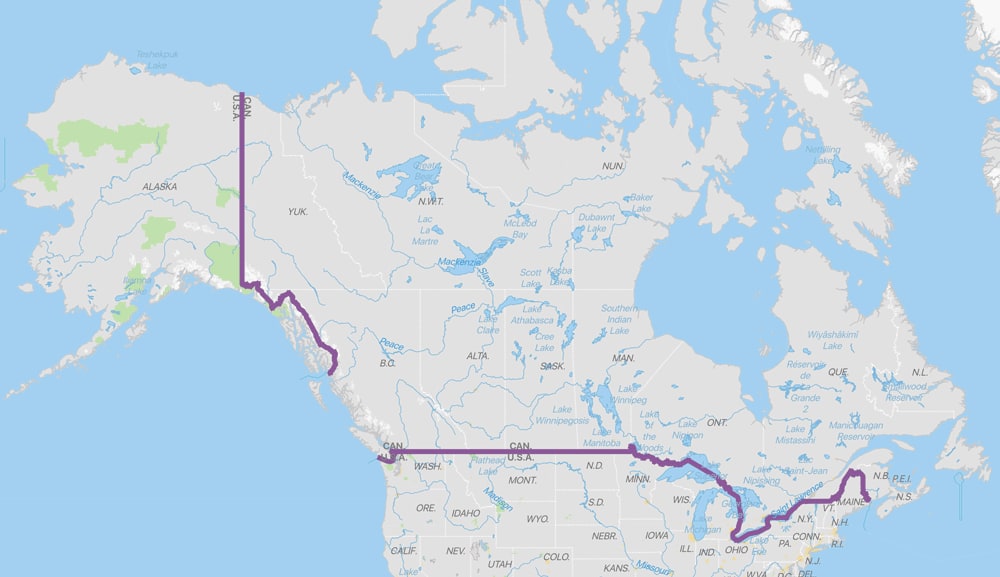

a national border (separates a state from neighboring states or international waters).

|  |

| |

|  |

| Figure 1: Cell membranes, skin, fences, firewalls, group divisions, and state borders as living system boundaries. | |

By respecting a boundary I mean approaching boundaries in ways that are gated on the consent of the person or entity on the other side of the boundary. For instance, the norm

“You should get my consent before entering my home”

has more to do with respecting a boundary than the norm

“You should look up which fashion trends are in vogue each season and try to copy them.”

Many people have the sense that the second norm above is more shallow or less important than the first, and I claim this is because the first norm has to do with respecting a boundary. Arguing hard for that particular conclusion is something I want to skip for now, or perhaps cover in a later post. For now, I just want to highlight some more boundary-related norms that I think may be acausally normal:

“If I open up my mental boundaries to you in a way that lets you affect my beliefs, then you should put beliefs into my mind that that are true and helpful rather than false or harmful.”

“If Company A and Company B are separate entities, Company A shouldn’t have unfettered access to Company B’s bank accounts.”

Here are some cosmic-scale versions of the same ideas:

Alien civilizations should obtain our consent in some fashion before visiting Earth.

Acausally separate civilizations should obtain our consent in some fashion before invading our local causal environment with copies of themselves or other memes or artifacts.

In that spirit, please give yourself time and space to reflect on whether you like the idea of acausally-broadly-agreeable norms affecting your judgment, so you might have a chance to reject those norms rather than being automatically compelled by them. I think it’s probably pretty normal for civilizations to have internal disagreements about what the acausal norms are. Moreover, the norms are probably pretty tolerant of civilizations taking their time to figure out what to endorse, because probably everyone prefers a meta-norm of not making the norms impossibly difficult to discover in the time we’re expected to discover them in.

Sound recursive or circular? Yes, but only in the way that we should expect circularity in the fixed-point-finding process that is the discovery and invention of norms.

How compelling are the acausal norms, and what do they imply for AI safety?

Well, acausal norms are not so compelling that all humans are already automatically following them. Humans treat each other badly in a lot of ways (which are beyond the scope of this post), so we need to keep in mind that norms — even norms that may be in some way fundamental or invariant throughout the cosmos — are not laws of physics that automatically control how everything is.

In particular, I strongly suspect that acausal norms are not so compelling that AI technologies would automatically discover and obey them. So, if your aim in reading this post was to find a comprehensive solution to AI safety, I’m sorry to say I don’t think you will find it here.

On the other hand, if you were worried that somehow acausal considerations would preclude species trying to continue their own survival, I think the answer is “No, most species who exist are species that exist because they want to exist, because that’s a stable fixed-point. As a result, most species that exist don’t want the rules to say that they shouldn’t exist, so we’ve agreed not to have the rules say that.”

Conclusion

Acausal trade is less important than acausal agreement-about-norms, and acausal norms are a lot less weird and more “normal” than acausal trades. The reason is that acausal norms are created through reasoning rather than computationally expensive simulations, and reasoning is something moral philosophy and common sense moral reflection has been doing a lot of already.

Unfortunately, the existence of acausal normativity is not enough to automatically save us from moral atrocities, not even existential risk.

However, a bunch of basic human norms to do with respecting boundaries might be acausally normal because of

how fundamental boundaries are for the existence and functioning of moral beings, and hence

how agreeable the idea of respecting boundaries is likely to be, from the perspective of acausal normative reflection.

So, while acausal normalcy might not save us from a catastrophe, it might help us humans to be somewhat kinder and more respectful toward each other, which itself is something to be valued.

- Acausal normalcy by (LessWrong; 3 Mar 2023 23:34 UTC; 204 points)

- “Charity” as a conflationary alliance term by (13 Dec 2024 7:53 UTC; 76 points)

- “Charity” as a conflationary alliance term by (LessWrong; 12 Dec 2024 21:49 UTC; 35 points)

- The (short) case for predicting what Aliens value by (LessWrong; 20 Jul 2023 15:25 UTC; 17 points)

- 's comment on “Charity” as a conflationary alliance term by (16 Dec 2024 8:31 UTC; 3 points)

I’ve mostly arrived at similar conclusions through Evidential Cooperation in Large Worlds (ECL; see, e.g., Lukas’s commentary). ECL adds a few extra steps that make the implications a lot clearer to me (though not to the extent of them actually being clear). I’d be curious how they transfer to acausal normalcy!

Set of cooperators. When it comes acausal normalcy, what is the set of all cooperation partners? I imagine it’s everyone who honestly tries to figure out acausal normalcy and tries to adhere to it, so that people who try to exploit it are automatically expelled from the set of cooperation partners? That’s how it works with ECL. There could be correlations between beings who are wont to cooperate vs. defect (be it out of ignorance), so this could rule out some moral norms.

Circular convincingness. In the ECL paper, Caspar cites some more and less formal studies of the efficacy of acausal cooperation on earth. They paint a bit of a mixed picture. The upshot was something like that acausal cooperation can’t be trusted with few participants. There were some arguments that it works in elections (a few million participants), but I don’t remember the details. So the step that the universe is big (possibly infinite) was critical to convince every actor that acausal cooperation is worth it and thus convince them that others out there will also consider it worth it.

Is this covered by Payor’s Lemma? I’m still trying to wrap my head around it, especially which of the assumptions are ones it proves and which are assumptions I need to make to apply it… It also looks a bit funky to me. Is the character missing from the typeface or is there meant to be a box there?

Power. Another problem that I feel quite uncertain about is power. In the extremes, someone powerless will be happy to acausally cooperate rather than be crushed, and someone all-powerful who knows it (i.e. there’s no one else equally or more powerful) has probably no interest in acausal cooperation. The second one of these beings is probably impossible, but there seems to be a graduation where the more powerful a being is, the less interested it is in cooperation. This is alleviated by the uncertainty even the powerful beings will have about their relative rank in the power hierarchy, and norms around pride and honor and such where beings may punish others for defections even at some cost to themselves. I don’t see why these alleviating factors should precisely cancel out the greater power. I would rather expect there to be complex tradeoffs.

That all makes me inclined to think that the moral norms of more powerful beings should be weighed more (a bit less than proportionally more) than the moral norms of less powerful beings. These powerful beings are of course superintelligences and grabby aliens but also our ancestors. (Are there already writings on this? I’m only aware of a fairly short Brian Tomasik essay that came to a slightly different conclusion.)

Convergent drives. Self-preservation, value preservation, and resource acquisition may be convergent drives of powerful beings because they would otherwise perhaps not be powerful. Self-preservation implies existence in the first place, so that it may be optimal to help these powerful beings to come into existence (but which ones?). Value preservation is a difficult one since whatever powerful being ends up existing might’ve gotten there only because its previous versions still value-drifted. Resource acquisition may push toward instilling some indexical uncertainty in AIs so that they can figure out whether we’re in a simulation, and whether we can control or trade with higher levels or other branches. I feel highly unsure about these implications, but I think it would be important to get them right.

Idealization. But the consideration of our ancestors brings me to my next point of confusion, which is how to idealize norms. You mention the the distinction between instrumental and terminal goals. I think it’s an important one. E.g., maybe monogamy limited the spread of STDs among other benefits; some of these are less important now with tests, vaccinations, treatments, condoms, etc. So if our ancestors valued monogamy instrumentally, we don’t need to continue upholding it to cooperate with them even though they have a lot of power over our very existence. But if they valued it terminally, we might have to! Perhaps I really have to bite bullet on this one (if I understand you correctly) and turn it into a tradeoff between the interests of powerful people in the past with weird norms and the interests of less powerful people today…

Positive and negative reinforement. When it comes to the particular values, especially reinforcement learning stands out to me. When a being is much smaller than its part of the universe, it’ll probably need to learn, so my guess is that reinforcement learning is very common among all sorts of beings. Buck once argued that any kind of stimulation, positive or negative, expends energy, so that we’re calibrated such that most beings who survive and reproduce will spend most the time close the energy-conserving neutral state. That sounds pretty universal (though perhaps there are civilizations where only resources other than energy are scarce), so that the typical utilitarian values of increasing happiness and reducing suffering may be very common too.

(When I was new to EA, I read a lot of Wikipedia and SEP articles on various moral philosophies. My impression was that reducing suffering is “not dispreferred” by all of them (or to the extent that some of them might’ve been explicitly pro suffering, it was in specific, exceptional instances such as retribution) whereas all other norms were either dispreferred by some moral philosophies or really specific. My tentative guess at the time was that the maximally morally cooperative actions are those that reduced suffering while not running into any complicated tradeoffs against other values.)

Unique optimal ethics. An interesting observation is that ECL implies that there is one optimal compromise morality – that anyone who deviates from it leaves gains from moral trade on the table. So my own values should inform my actions only to a very minor degree. (I’m one sample among countless samples when it comes to inferring the distribution of values across the universe.) Instead my actions should be informed by the distribution of all values around the universe to the extent that I can infer it; by the distribution of relevant resources around the universe; and by the resources I have causally at my disposal, which could put me in a comparatively advantageous position to benefit some set of values. I wonder, is there one optimal acausal normalcy too?

Should this read “absence of a (physically) causal communication channel”? I’m confused by this sentence as stated

Very interesting post, thanks for writing this!

I’m wondering to what extent this is the exact same as Evidential Cooperation in Large Worlds, with which you don’t need simulations because you cooperate only with the agents that are decision-entangled with you (i.e., those you can prove will cooperate if you cooperate). While not needing simulation is an advantage, the big limitation of Evidential Cooperation in Large Worlds is that the sample of agents you can cooperate with is fairly small (since they need to be decision-entangled with you).

The whole point of nesting simulations—and classic acausal trade—is to create some form of artificial/”indirect” decision-entanglement with agents who would otherwise not be entangled with you (by creating a channel of “communication” that makes the players able to see what the other is actually playing so you can start implementing a tit-for-tat strategy). Without those simulations, you’re limited to the agents you can prove will necessarily cooperate if you cooperate (without any way to verify/coordinate via mutual simulation). (Although one might argue that you can hardly simulate agents you can’t prove anything about or are not (close to) decision-entangled with, anyway.)

So is your idea basically Evidential Cooperation in Large Worlds explained in another way or is it something in between that and classic acausal trade?

Isn’t an acausal norm equivalent to a goal-directed norm? If not, then what’s the difference?