James Lovelock (1919 – 2022)

The real job of science is trying to make science fiction come true.

Britain’s greatest mad scientist died recently at 103.

We’ll get to his achievements. But I can’t avoid mentioning the ‘Gaia hypothesis’, his notorious metaphor gone wrong that the Earth is in some sense a single organism whooaa. But him being most famous for this is like thinking Einstein’s violin playing was his best stuff. [1]

Lovelock was raised as a Quaker, to which he credits his independent thinking (he was a conscientious objector in WWII). Also:

“His family was poor, too poor to pay for him to go to university. He later came to regard this as a blessing because it meant he wasn’t immediately locked into a silo of academia. Somehow, he created an education for himself, taking evening classes that led, when he was 21, to the University of Manchester.”

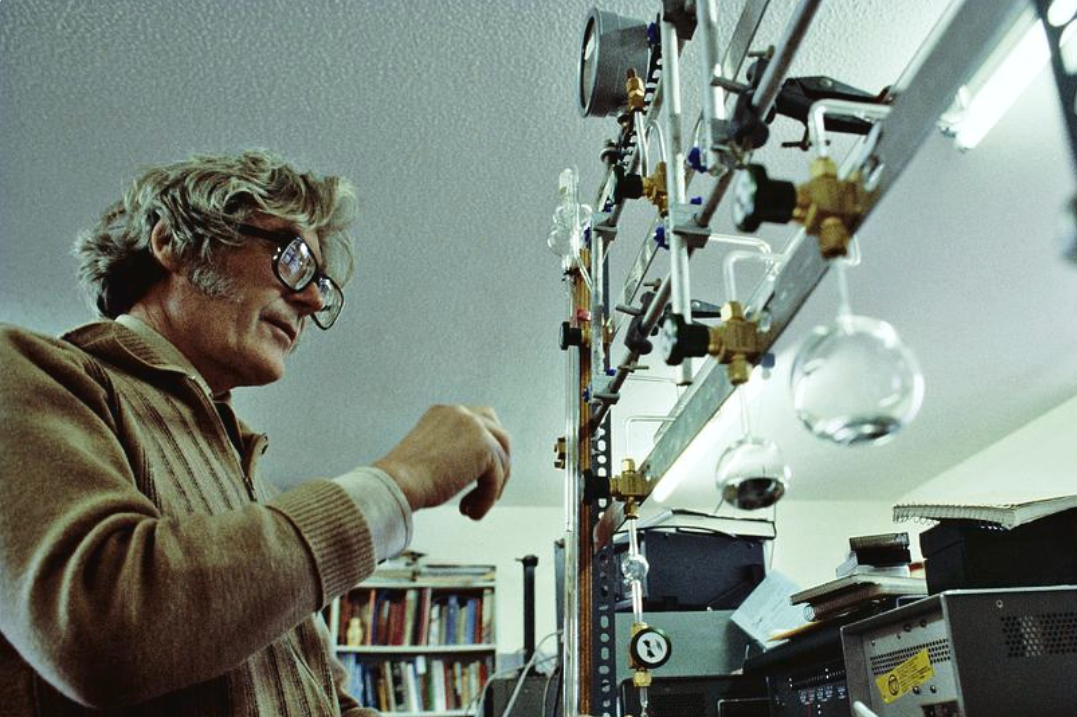

He quit work and left academia forever in 1964, instead running a one-man “ten foot by ten foot” lab from his garden in the West Country,[2] living off consulting work for NASA, Shell, HP, and MI5 and royalties from 40 inventions.

Chromatography, &, modern environmentalism

By far his biggest coup was building the electron capture detector in 1957 during his second PhD, the world’s most sensitive gas chromatograph (way of detecting chemicals in air).

When Lovelock first developed the ECD, the device was at least a thousand times more sensitive than any other detector in existence at the time. It was able to detect chemicals at concentrations as low as one part per trillion—that’s equivalent to detecting a single drop of ink diluted in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

He became curious about what the visible air pollution he saw was due to. He picked the notorious CFCs just because they were conspicuous, becoming the first person to notice the global consequences of Thomas Midgley’s almighty fuckup fifty years earlier. (CFCs later turned out to be the cause of the hole in the ozone layer, i.e. millions of skin cancer cases.) He went to Antarctica in person, “partially self-funded”, to check if they were there too, because why not. He screwed up the interpretation though, writing in Nature “the presence of these compounds constitutes no conceivable hazard”.

The ECD revolutionised atmospheric chemistry and so the study of air pollution, still one of the more important causes of premature death.

On the lawn of the house peacocks strut and mew; a pair of barn owls have built their nest above the Exponential Dilution Chamber, a sealed upper room that was built in order to calibrate the Electron Capture Device. In the garden stands an off-white baroque plaster statue: the image of Gaia.

The device was so sensitive that it showed traces of pesticides in animal tissues all over the world, including DDT. Since that led to Silent Spring, he probably helped along the perverse return of organic farming and the anti-chemicals paranoia of the second half of the C20th.

Not that he was ever one of those:

Too many greens are not just ignorant of science, they hate science… [Environmentalism is like a] global over-anxious mother figure who is so concerned about small risks that she ignores the real dangers. I wish they would grow up [and focus on the real problem]: How can we feed, house and clothe the abundant human race without destroying the habitats of other creatures?

Some time in the next century, when the adverse effects of climate change begin to bite, people will look back in anger at those who now so foolishly continue to pollute by burning fossil fuel instead of accepting the beneficence of nuclear power. Is our distrust of nuclear power and genetically modified food soundly based?

Later, he was notable for sounding the retreat (humans should start leaving coastal settlements) and for proposing geoengineering (or as he called it, “planetary medicine”). Other climate scientists were horrified, no doubt correctly, but I’m not convinced it was for the right reasons—“There is absolutely no evidence that climate engineering options work or even go in the right direction. I’m astonished that they published this.” Hm, I wonder why there’s no evidence?)

Here’s a representative sample of the scruffy green opinion about him. The feeling is mutual:

“Carbon offsetting? I wouldn’t dream of it. It’s just a joke. To pay money to plant trees, to think you’re offsetting the carbon? You’re probably making matters worse. You’re far better off giving to the charity Cool Earth, which gives the money to the native peoples to not take down their forests.”

Aerospace engineering, &, exo- and astro-biology

In 1961 NASA hired him to build a gas chromatograph for their first unmanned moon landing, one purpose of which was to check if there was life there. He did the same for the Viking Mars lander in the 70s. This was one of the founding projects of exobiology and astrobiology, now a perfectly respectable science with PhDs and everything.

One truly crazy idea for human survival appears at regular intervals in the media and in the minds of the venturesome. This is the notion that Mars could be a refuge for humanity if our life on Earth was in danger of being terminated… the Martian desert is wholly inimical to all conceivable forms of Earth life. The atmosphere is about a hundred times thinner than the summit of Everest and it provides no shield against cosmic radiation or the ultraviolet radiation of the Sun. The thin air of Mars is 99 per cent CO 2 and utterly unbreathable. There are traces of water on the planet, but it is as salty as the waters of the Dead Sea and undrinkable. The pioneer and would-be spacefarer Elon Musk has said he would like to die on Mars, though not on impact. Martian conditions suggest death on impact might be preferable.

Though 90% nonsense,[3] Gaia actually led to a sound principle in astrobiological surveying: “look for weird out-of-equilibrium chemistry. Any weird chemistry.”

It also led to the creation of something called ‘Earth system science’, which has come up with a testable form, good for them.

Biology

The fluid dynamics of airborne pathogens

A very early study of how bad droplets and aerosols are per infected person per volume.

Blood

He discovered the role of minerals like calcium ions in blood clotting.

I can’t find anything on his work on preserving sperm for artificial insemination, apparently economically crucial. I worry that is his one negative invention.

Cryonics

He invented the field! Here’s a must-watch video about his successful work on freezing and reanimating hamsters, during which he reinvented the microwave oven from scratch. He discovered the solutes you need to prevent thermal shock.

MI5

Suddenly, cheerful espionage:

In 1965, when he was in the U.S., he was asked if there was any way to find people hiding in dense tropical rainforests. This was not a casual question; America’s disastrous involvement in Vietnam had begun. His possible solution led to meetings with the CIA, which seemed to go nowhere.

...”I now know that the CIA and other American agencies did not make use of my idea until years later...”

He was more successful with British intelligence operatives. They were looking for a way to track Soviet spies. His idea was to use a chemical marker on their cars that sensors could detect. The British spies were keen, but he was puzzled by the concern they showed for the health of their targets.

“I was baffled. I imagined that few would care about the health hazards of a KGB agent in London. Not so: It was almost as if they regarded the opposition as merely rival civil servants and that they at least deserved the care needed to ensure a long and well-earned retirement at pension time.”

Actually a little too edgy for me. They only revoked his security clearance when he turned 94, which he bragged was a record.

What I love about Lovelock is that is he spouted galaxy-brain hypotheses and also solved actual problems. He bridged hippie environmentalism and the swivel-eyed transhumanism we know and love. His was one of the last vestiges of the grandiose and yet real spirit of 1950s engineering, and so the good side of the Victorian mind. We could use another million of his sort of pro-nuclear environmentalist, too.

Appendix: Prolegomena to a future biography

His last book, published at the age of 99, concerned artificial superintelligence taking over the world. But don’t worry, he was quite sure it’ll be benevolent—in fact a superior caretaker of the poor animals. His take is misguided but characteristically happy-go-lucky and metaphysical.

We are unique, privileged beings and, for that reason, we should cherish every moment of our awareness. We should now be cherishing those moments even more because our supremacy as the prime understanders of the cosmos is rapidly coming to an end.[4]

“He is withering about the attempt of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to forge a consensus, a word that he says has no place in science.”

He was mates with William Golding, the misanthropic novelist. An odd couple! Golding is also to blame for the hippie stylings of Gaia:

I was quite excited telling Bill about it, and he got excited too and he turned to me and said, “Look, if you’re going to come up with a big idea like that you’d better give it a proper name,” and I said, “What do you suggest?” And he said, “I suggest you call it Gaia.”′

Ouch

“Maybe they’ll synthesise food. I don’t know. Synthesising food is not some mad visionary idea; you can buy it in Tesco’s, in the form of Quorn. It’s not that good, but people buy it. You can live on it.”

Why not:

23-year old James Lovelock… cradling a baby in his arms who would grow to become the world’s best known scientist, Stephen Hawking… Hawking’s father… spent much of his working life at the NIMR studying parasitology. Lovelock was doing research at the time of the encounter on sneezing and disinfection.

lol:

Tentatively I mention something Teddy Goldsmith had told me, that Lovelock found out after his father died that he was a gypsy.

“A gypsy? Really? He said that?” Lovelock says. “I don’t think so. But he may have been a Baffinlander…”

“A what?”

“An eskimo,” Lovelock says, without blinking. “Do you notice a Mongolian cast to my features? That comes from my father. When I was working in America, we were quite poor. I used to sell my blood to the hospital there. And I discovered I have a rare type thought only to occur in Baffinland.

“From Baffin to boffin,” he adds, with barely a pause, “in one generation.”

He seems to have struggled to ever be unoriginal:

He is wont to refer to the traditionally privileged classes as Normans and to the rest as Saxons. “Most scientists are Saxons,” he says, clearly including himself. “Margaret Thatcher was the first Saxon Prime Minister.”

I’ve only read two of his 30+ books and I am very sure that there are dozens more ingenious ideas and absurd stories in the rest—not least his long correspondence with the all-time great crank Lynn Margulis or his giant archive.

- ^

The original piece is actually fine. Some scientists admit it ended up quite useful, closing the loop of Darwinism in a cool way. “Life evolves in response to environmental change, but the environment also evolves in response to biological change.” But the books are a bit embarrassing.

But there’s no denying this kind of shit was most of it: “If we continue to despoil her,” Lovelock says flatly, “the rest of creation will, as part of Gaia, unconsciously move the Earth itself to a new state, one where we humans may no longer be welcome.”

- ^

“The problem,” Lovelock says, “is that some compounds react with palladium, so I thought if I coated the inside of the tube with the right kind of impervious layer, the hydrogen would still go through but the other substances wouldn’t be able to see the palladium and all would be well. And to my joy I discovered that if I treat the tube with fluorine gas, of which I have a small cylinder here”—he points to a white cylinder on the floor—“it forms a fluoride, a bit like anodised aluminium, which lets the hydrogen through but leaves everything else unchanged, as I hoped.”

“If I was in an ordinary lab, I’d have hell’s delight to be allowed to do this. Health and Safety would be around saying, ‘Oh, no. Can’t possibly have fluorine in the lab. Could cause an explosion. Palladium? Don’t know about that. Sounds toxic… Could be carcinogenic…’ But here I can do what I want.”

The palladium transmodulator, I realise at this point, is a refinement of the original Electron Capture Detector, invented 34 years ago and still going strong.

“Oh yes, it’s selling like hot cakes”

- ^

JL: “[Gaia] may turn out to be the first religion to have a testable scientific theory buried in it.”

I ask him: isn’t such talk about Gaia as a religion playing into the hands of his critics?

JL: “Well, the neo-Darwinists—Dawkins and so on—are really the Jesuits of modern science. It’s they who have made a dogma of Darwinism. I think it’s because they’ve been embattled for so long with Creationists, particularly in America. But you can’t deny the presence of religious sensibility.”

I ask him if he ever thinks he should have given Gaia another name.

“Yes”, he says. “Quite often. But I was determined not to have an acronym. I hate acronyms. It was William Golding who thought it up. Perhaps you know? We were neighbours when I lived in Wiltshire. Actually, when he first suggested it I thought he said ‘gyre’—as in Yeats’ ‘turning and turning in the widening gyre’. Now that would have been really far-fetched.”

- ^

“The mistake I think we made was to continue to reason classically. We made this mistake because of the nature of speech, either spoken or written, and the fissiparous tendency of human thinking. We know that our friends and lovers are whole persons. It may seem sensible at various times to consider their livers, skin and blood to understand their special function, or for purposes of medicine, but the person we know is much more than the mere sum of these parts. As I see it, the logical problem with speech is that it proceeds step by step linearly. This is fine for the solution of essentially static problems and has served us well; it has led logicians such as Frege, Russell, Wittgenstein and Popper to offer comprehensible explanations of our world. Now, when I look back on the long arguments I had over Gaia with evolutionary biologists in the Western world, they seem to have been arguments at cross purposes. From the beginning I saw Gaia as a dynamic system. I knew instinctively that such systems cannot be explained in linear logical terms, but I did not know why.”

From another writer, you would be perfectly correct to ignore this as romantic nonsense. An irony is that he collides names with the actual Linear Logic, which is quite able to model things like his squooshy dynamics.

Thank you so much for sharing!

I was only confused by this paragraph:

Why do you consider this potentially negative?

Seems like it would contribute to the profitability and feasibility of factory farming.

That makes sense! I failed to think of non-human applications.

Edit: “economically crucial” should have been a hint.

Truly an amazing guy. See also how he invented an early microwave to make animal cryonic experiments more humane.

Came here to share this also! What a great story.

oh that guy