How Congressional Offices Process Constituent Communication

For anyone interested in facilitating constituent communication (emailing, calling, meeting with the legislators that represent you) to influence policy, it will be helpful to understand how offices process these various communication channels. This is what is referred to as the “formal process” in our post about the effectiveness of constituent communication on changing legislator’s attitudes, as it represents the mechanism offices have put in place to systematically intake and consider constituent opinion. I’ll start with explaining the general office structure, and then get into the process itself.

Office Structure

Before talking about how offices process communication, it’s important to have a rough understanding of who makes up a congressional office. Offices are split into two different locations, an office in DC and an office in the district, and though the roles will vary a lot office to office, a number of positions are common:

Leadership

Member: The elected official.

Chief of Staff (CoS): “Chiefs of staff serve as the key adviser to the elected official, managing staff and ensuring the smooth operation of day-to-day activities.”

Deputy Chief of Staff (DCoS): “Typically oversees a few policy issues [and manages] the Chief of Staff’s schedule, personal correspondence, and any overflow work delegated by the Chief of Staff.”

District Director (DD): “This person is responsible for handling all state-based operations for the member, including most constituent-facing functions.”

Legislative Team

Legislative Director (LD): Oversees legislative staff and helps develop legislative strategy for the office.

Legislative Assistant (LA): “These staffers are responsible for conducting in-depth research, analyzing policy issues, drafting legislation and advising the member of Congress on legislative matters.”

Legislative Correspondent (LC): “Responsible for drafting letters in response to constituents’ comments and questions and also generally responsible for a few legislative issues”

Communications Team

Communications Director (CD) or Press Secretary (PS): “Responsible for Member’s relationship with media; is the liaison for the local and national press; issues press releases”. In the House these are often combined into one role, but many Senate offices have both, where the CD will focus more on overall strategy and the PS more on handling immediate items.

Press Assistant (PA): “Press assistants support the communications team by facilitating media interactions, drafting press releases and social media posts, managing media inquiries and coordinating public relations efforts.”

District Facing Team

Caseworker (CW) or Constituent Service Representative (CSR): Mostly district office based and focus on helping constituents deal with any problems with federal agencies.

Administrative Team

Staff Assistant (SA): “The most common entry-level position on Capitol Hill, the Staff Assistant handles all front office responsibilities, answers phones, schedules tours, and often supervises the mail program. Staff Assistants also often serve as intern coordinators”

Scheduler: “Schedulers are responsible for coordinating and managing the daily and long-term schedules of the elected official and arranging meetings, briefings and events”

Systems Administrator (SyA): “This person oversees all the technology in the office” but this position is often outsourced to a third party.

Intern: “Interns assist with research, administrative tasks and constituent inquiries”

Generally speaking, Representatives have a maximum of 18 full-time employees and often less[1] while Senators will employ between 35 and 60 staffers in total. Employees are roughly evenly split between the district and DC offices, with slightly more in the DC office[2]. Given previous estimates that 75% of those in the DC office are focused on constituent communication, it’s likely that over 33% of a given office’s staff is devoted to processing, and responding to, constituent communication on issues.

What’s The Process?

So you’ve communicated with your member, now what happens? The entire process is well drawn out here, but once your communication has been received, it generally follows seven basic steps:

Receive constituent contact and verify it’s from a constituent, then sorting it into the different workstreams

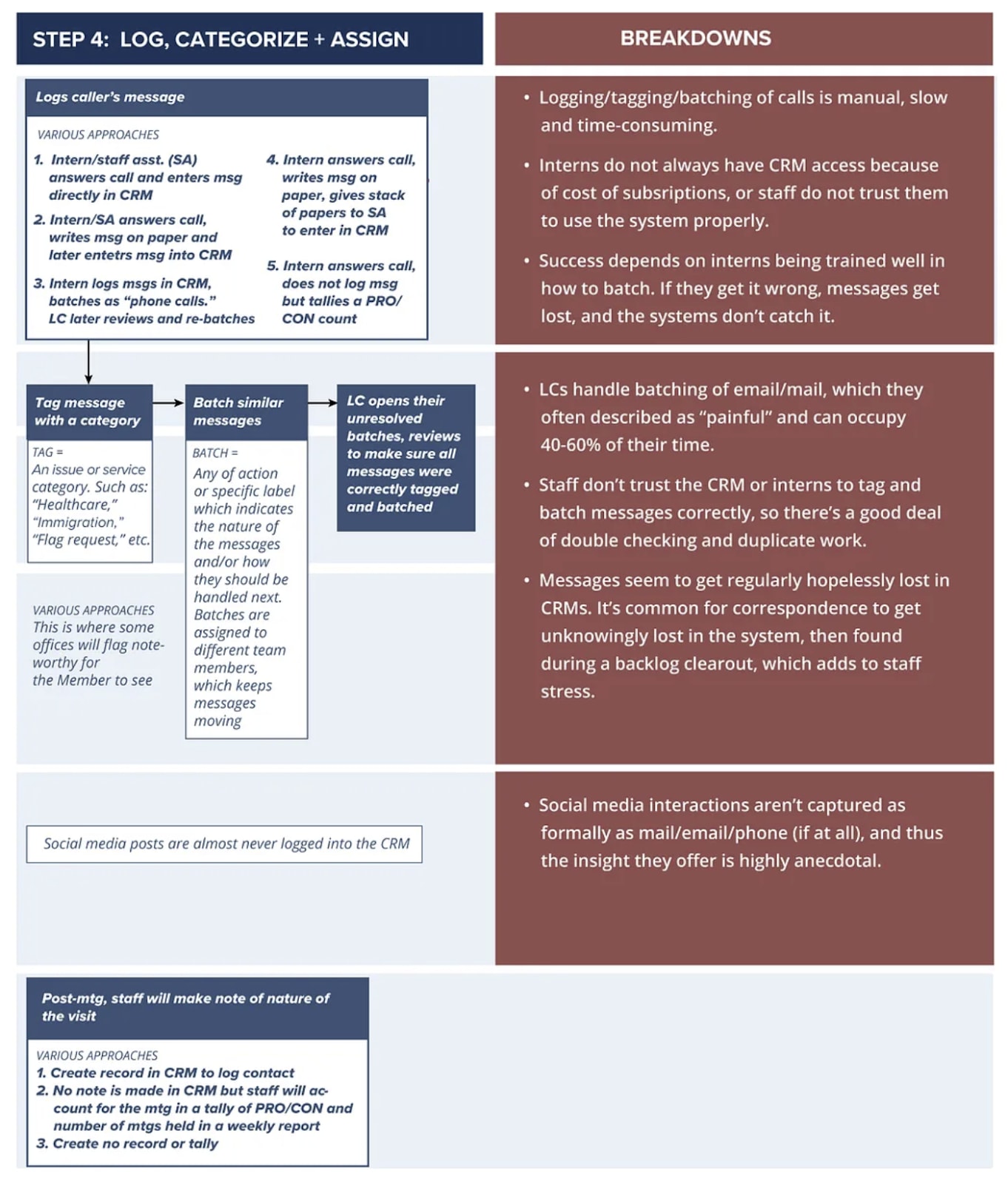

Log, categorize, and assign: Recapture the message in the office’s system, categorize them together with similar messages, and assign them to a staffer for review and follow-up.

Respond: Locate an existing response to this topic or draft a new one.

Create a “mail report”: Summarize the incoming communication topics into a presentation for others in the office (done by 92% of offices).

Step 1: Receiving Communication

Incoming messages are first categorized by the type of communication being made, generally slotting messages into one of the following categories: a constituent service request (e.g., a flag request), request for assistance with a federal program (e.g., veterans’ benefits), meeting request, or sharing input on and/or looking to learn the Member’s stance on a specific issue. Relevant here are the inquiries outside of service and assistance requests.

To get a sense of the receiving process, it’s worth noting the quantity of communication received and the type of communication. First looking to quantity, 2013 data found high variance in communication received between offices:

19% of offices surveyed received over 2000 contacts weekly, 39% receiving between 1000 and 2000 weekly and 42% receiving less than 1000. What’s more is that these numbers are likely much higher now, as there’s been a consistent, increasing trend of communications over time.

For example, the average House office received an estimated 12,500 communications per year in the 1970s, but in 2020 received an estimated 65,000 emails alone, a 5x increase[3]. And that’s just emails. In terms of total communications received, Congress received 105 million communications in 2000 which increased to over 200 million by 2004, nearly doubling in only four years. This effect is particularly acute for senate offices, some receiving over 25,000 pieces of incoming correspondence per week, indicating they process over 1,300,000 each year[4].

This is because the number of constituents represented per member has grown dramatically over time, starting at 75,000 per district in 1911 and rising to around 650,000 per district in 2008, nearly a 10x increase. The funding simply has not matched this increase and has even lead to a decrease in overall staff over time, most funding increases now going to the executive branch which gets 120x the funding. Despite all of this, it is worth noting that one survey indicated 71% of offices still feel they have the resources to handle all of this incoming information, though this is likely also due to a trend of turning this messaging into data points over time and engaging less deeply.

Coming back from this digression, we can also (in broad strokes) paint a picture of what sort of communication is received. As a lower bound, staffers estimate at least 66% of incoming messages are form emails on average, pre-generated templates organizations put out that only require someone to write their name at the bottom, but these could make up as much as 90% of total messages received.

Step 2: Log, Categorize, & Assign

There is no uniform practice across offices for managing intake of messages or the subsequent logging process, but one commonality is that this is almost always done by junior staff and interns, and for some this may be the main way they pass most of their time.

Step 3: Respond

This process generally starts with the LC reviewing, editing, and researching responses, with the LA frequently helping across the stages. If there’s already a pre-existing response matched to the subject of the message, the LC will normally match that up and then get largely procedural approval from another staff member.

If there’s no pre-existing message, the LD and CoS will often be brought in to help generate new responses, and will almost always need to approve those new responses before they can be used. It’s worth noting that the member will sometimes be involved in the process though, one study finding 28% are involved with approving the application of pre-existing messages, 26% with reviewing and editing new responses, and 42% approving new responses.

Step 4: Create a Mail Report

Mail reports see a lot of variation from office to office, but thankfully one 2015 study has captured some of that variety:

What’s included in a mail report?

34% include every issue that emerged during the time period, along with number of contacts for that issue

11% go further to list a breakdown of the pro/con stances that constituents hold

49% list the “top” incoming issues during the time period, most commonly the top 3 or 5, but ranging from 1 to 25

This tracks with responses from staffers elsewhere about what is required to make an office feel like an issue is important. Two responses given were “if there is a lot coming” or “enough to make a batch”, indicating the importance of a certain critical mass of communication for an office to take an idea seriously.

25% directly included constituent text, where some different criteria for inclusion were:

If it is unique, interesting or important (in 5 offices)

If it represents a large volume of contacts the office received (in 5 offices)

If it’s needed to help the staffer seek advice on how best to respond to a sensitive or highly technical contact (in 5 offices)

If another staffer requests it (in 3 offices)

If the sender was an important person in the district (i.e. an elected official, local leader, etc.) (in 1 office)

17% only include the rough aggregate information mentioned below

Other statistics included in reports:

71% include total volume of incoming correspondence, listing the total number of new contacts that were logged into the correspondence database for the time period covered by the report

53% include total volume of outgoing correspondence, indicating the total number of responses that were sent out to constituents for the time period covered by the report.

29% include total volume of pending correspondence, indicating the number of contact records that are still awaiting a response from the office

23% include length of time mail has been pending, identifying the age of mail that remains in their system.

20% include a status update on pending responses, listing the responses that are currently in the process of being drafted, edited or approved.

Frequency of reports:

2% compile them on a daily basis, 66% weekly, 5% bi-weekly[5], 7% monthly, 1% annually, 9% “as needed”, 2% at random intervals, and 8% never

For those who do so as needed, the motivations for creating one were: “when there was a big or high priority issue (2 offices); when a large campaign is received or a large increase in correspondence volume is observed (3 offices); when certain issues come to the House floor (1 office); when the “content of correspondence is deemed proper to share with other staff” (1 office); or at the request of another staffer in the office (1 office)”

Who receives the reports?

50% of offices share with the Member

78% with the Chief of Staff

68% with the Legislative Director

31% with the Deputy Chief of Staff

29% with the Communications Director

44% with the Legislative Assistant

30% with the Staff Assistant

19% with the System Administrator

13% with the Interns

- ^

This is due to budgetary limitations, as around 2021 offices only had $1.5 million to spend, which can’t easily support 18 full time salaries.

- ^

We could assume that this might be roughly 55% in the DC office, 45% in the District office

- ^

A similar rate of increase (4x) was found between 1995 and 2004 specifically.

- ^

One specific office saw an increase from 9,300 annual communications in 2001 to 123,000 in 2017, a 13x increase.

- ^

Every other week

Executive summary: Congressional offices have a structured process for handling constituent communications, involving multiple staff roles and steps to log, categorize, respond to, and report on incoming messages.

Key points:

Office structure includes leadership, legislative, communications, district-facing, and administrative teams, with staff split between DC and district offices.

Communication process involves 4 main steps: receiving and verifying, logging and categorizing, responding, and creating mail reports.

Offices receive high volumes of communications, with significant increases over time (e.g., 5x increase in emails from 1970s to 2020).

Majority of incoming messages (66-90%) are form emails, processed mainly by junior staff and interns.

Mail reports summarize communication trends, with varying content and frequency across offices.

Resource constraints impact offices’ ability to handle increasing communication volumes, though 71% feel they have sufficient resources.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.