Facilitating international labor migration via a digital platform

TLDR: This report explores the idea of incubating a nonprofit organization that would support temporary international labor migration using a digital information and job-search platform paired with transparent, low-cost facilitation.

We’re seeking people to launch this idea through Ambitious Impact (Charity Entrepreneurship) next August 12-October 4, 2024 Incubation Program. No particular previous experience is necessary – if you could plausibly see yourself excited to launch this charity, we encourage you to apply. The deadline for applications is April 14, 2024. Apply here.

Research Report:

Facilitating international labor migration via a digital platform

Author: Filip Murár

Review: Aidan Alexander, Samantha Kagel, Sam Hilton

Date of publication: February 2024

Research period: 2023

We are grateful to the experts who took the time to offer their thoughts on this research: Professor Mushfiq Mobarak, Professor Samuel Bazzi, Dr. Tutan Ahmed, Jason Wendle, Prerna Choudhury, and Pall Kvaran.

We thank Professor Mushfiq Mobarak for bringing this topic to our attention.

For questions about the content of this research, please contact Filip Murár at filip@charityentrepreneurship.com. For questions about the research process, please contact Sam Hilton at sam@charityentrepreneurship.com.

Executive summary

International labor migration has the potential to create large financial returns for workers and their families. While permanent migration is often not legally possible for citizens of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), temporary labor migration – also known as guest work – is highly prevalent. LMICs in regions such as South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Africa collectively send millions of workers every year to richer countries in neighboring regions, such as countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council, Malaysia, or Singapore. However, this type of migration is a complex, risky, and often costly process for the migrants, reducing the returns for those who manage to migrate and incurring losses for those who don’t.

Potential migrants typically learn about and get access to job opportunities via networks of intermediaries who use their privileged position to charge exorbitant fees – often multiples of people’s annual salaries – and extract value from the market.

Existing intermediaries often have incentives to underinform or misinform their clients, resulting in migrants accepting jobs with lower-than-expected salaries and worse working conditions. Individuals who start the application process but, for whatever reason, fail to migrate often suffer huge losses and sink their families into debt.

The idea behind this charity is to create a “one-stop shop” service to support potential migrants along the process of learning about working abroad, finding the right job, and fulfilling the necessary requirements for successful migration. It would achieve this by creating a digital platform featuring a job board paired with free, transparent information on the pros & cons and the practicalities of migrating, personalized one-to-one support (via a call center), and recommendations to high-quality third-party services.

While there are many existing organizations that offer some of these services, we have not found any that provide all of them on a unified platform. Additionally, the existing market is dominated by for-profit organizations that often exploit individuals’ motivation and extract value from them. A new, impact-oriented nonprofit organization operating in this space could create large economic and welfare gains. There is good evidence that well-managed international labor migration can create such returns, and the barriers to achieving this are also relatively well understood. While the theory of change behind this charity is somewhat complicated, most of the activities have been done by past actors, demonstrating their tractability.

We have modeled several cost-effectiveness estimates for this charity. A model that assumes the charity would only reduce the cost of migrating, and not result in a counterfactual increase in migration rates, estimates 13 DALY-equivalents per $1000 spent (or, equivalently, $78/DALY) for a charity operating in Nepal. If the charity charged its successfully-migrating users a modest $50 fee, it would achieve 25 DALYs per $1000 (or $39/DALY). Lastly, if it managed to create some counter-

factually additional migration, its cost-effectiveness would be 38 DALYs per $1000 (or $26/DALY), even in the absence of fees. This means that the charity would be more cost-effective than the top charities recommended by the charity evaluator GiveWell.

We have several uncertainties about this charity’s operation, including how difficult it would be to gain users’ attention their trust for them to use the platform and benefit from it; how many (potentially costly) personalized services the charity would have to offer on top of the digital platform itself; and where it should aim to operate.

The experts we spoke with agreed that misinformation, high fees, and exploitative practices are extremely prevalent, and that solutions to address these problems are needed in multiple countries. While they have warned that an information-only platform may fail to attract users and effectively support them on their migration journey, they believed that a more personalized recruitment/facilitation service could achieve this, potentially at significant financial and well-being benefits to the migrants.

Our main model of this charity assumes that most migrants would go to established destination countries with relatively saturated labor migration markets. Therefore, we did not assume that the charity would create additional, counterfactual migration. However, we think that there is a potential upside where this charity manages to work directly with employers in destination countries (potentially in less well-establishedd markets) and thereby create new migration that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. Given the large financial returns to working abroad, this could significantly increase the charity’s impact and cost-effectiveness. However, such expansion might be complex and costly to undertake, so we haven’t factored it into our main models.

Overall, our view is that this is an idea worth recommending to future charity founders.

1 Introduction

This report evaluates the idea of a digital “one-stop shop” platform for international migrant workers from LMICs. The aim is to assess how promising it is for the Charity Entrepreneurship (CE) Incubation Program.

CE’s mission is to cause more effective non-profit organizations to exist worldwide. To accomplish this mission, we connect talented individuals with high-impact intervention opportunities and provide them with training, colleagues, funding opportunities, and ongoing operational support.

CE researchers chose this idea as a potentially promising intervention within the broader areas of the best targets within the Sustainable Development Goals. This decision was part of a multi-month process designed to identify interventions that are most likely high-impact avenues for future non-profit enterprises.

This process began by listing hundreds of ideas, gradually narrowing them down, and examining them in increasing depth. We use various decision tools such as evidence reviews, theory of change assessments, group consensus decision-making, case study analysis, weighted factor models, cost-effectiveness analyses, and expert inputs.

This process is exploratory and rigorous but not comprehensive – we did not research all ideas in depth. As such, our decision not to take forward a non-profit idea to the point of writing a full report does not reflect a view that the concept is not good.

2 Background

2.1 Cause area: Sustainable development goals

In this research round, CE focused on identifying promising ideas for new charities within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Researching these two areas meant evaluating ideas from various fields, including maternal health, chronic diseases, neglected tropical diseases, migration, public administration governance, and education.

Best targets within the Sustainable Development Goals

The SDGs are a mechanism designed to focus global action toward specific objectives. Like the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) before them, these goals aim to redirect efforts and funding toward an agreed-upon list of priorities. They were agreed to by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly as part of its post-2015 ambitions (Wikipedia contributors, 2023). Unlike the MDGs, the SDGs have grown significantly in number of goals and targets (from eight to 17 and 21 to 169, respectively).

Figure 1: The United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

The global community succeeded in some of the most critical MDGs. MDG targets related to poverty reduction and safe drinking water, among others, were met. Despite missed targets, observers have noted the role of a concise list of eight priorities in focusing energies and driving progress. By drawing comparisons to the MDGs, observers have criticized the SDGs for being too many and too broad (Lomborg, 2023).

Progress toward achieving SDG goals has stalled. Only 15% of SDG targets are on track to completion, 48% are moderately or severely off-track, and 37% are regressing or stagnating (United Nations Publications, 2023).

The purpose of this research round was to investigate if a nonprofit organization of the style CE incubates could support the progress toward the goals and associated targets cost-effectively. We used the list of goals from the Copenhagen Consensus’ Halftime to the SDGs project as an initial departure point, listing all interventions prioritized in that project and supplementing the list with research from other sources, such as the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel’s smart buys in education (Banerjee et al., n.d.), and our own brainstorming and consultation exercise.

2.2 Topic area: Supporting international migrant workers via better information and facilitation of services

Why care about international labor mobility

There is a staggering amount of income inequality between countries. Some 60% of the variability in global incomes can be explained by people’s country of citizenship (Milanović, 2010). This inequality exists even for people with the same skills: The exact same worker may earn 10+ times more money (in nominal terms) in some countries than in others (Clemens et al., 2008).

One reason these differences exist is that much of the economic productivity of a worker is determined not by their work itself but by the economy of their place of work. Workers providing services in higher-income places create a greater economic value than workers providing similar services in lower-income places. Regionally, such differentials will often result in a reallocation of labor, with workers seeking out jobs in places where productivity and wages are higher (such as in cities instead of rural areas). However, internationally, significant differences in productivity and wages may persist in the long term due to a range of legal and practical barriers preventing workers from migrating and getting higher-paying jobs.

While many of these returns are only theoretical and unrealized, there is growing evidence that international labor mobility can be transformative for families experiencing poverty. For instance, the families of the winners of a visa lottery that allowed some Bangladeshi citizens to migrate for work to Malaysia experienced a 109% increase in their household incomes (Mobarak et al., 2023). Observational evidence also shows that employment abroad allows workers to send back home considerable amounts of money as remittances and that a 10% increase in remittances is, on average, associated with 3.5% decline in the share of people living in poverty (Adams, 2009).

The potential benefits are, in reality, reduced by a range of factors:

Overcharging by intermediaries: Intermediaries – i.e., individuals and organizations that assist people with getting jobs abroad – often capture 10-30% of the monetary returns to migration (Migration Data Portal, 2021).

Exploitation by intermediaries and employers: Intermediaries and employers have a lot of power over migrant workers and often abuse it. For instance, migrants’ passports are often withheld by intermediaries or employers, thereby not allowing them to switch to another intermediary or a different employer (a so-called “hostage mechanism”).

Migration via illegal means, which benefits some migrants but puts many at risk of harm, exploitation, and financial loss.

Extensive misinformation, which leads to migrants making suboptimal decisions or decisions they later regret and attempt to revert.

Migration failure: As a result of misinformation and fraudulent practices, people often fail to migrate – in as many as 15-30% of cases in India and Bangladesh. This typically incurs a financial loss of several hundred dollars.

Opportunities for charitable interventions

Governments of migrant-sending countries, as well as intergovernmental organizations, have been trying to address the issues discussed above. So far, however, top-down approaches have only had limited success. For example, the International Labor Organization (a UN agency) and the Institute for Human Rights and Business (a think thank) have been pushing for all costs to be covered by employers – the so-called “Employer Pays Principle” (IHBR, n.d.). However, this has yet to happen. Governments of countries like Nepal have also tried to set ceilings on the fees intermediaries can charge; however, these are often not followed in practice (Amnesty International, 2017; The Kathmandu Post, 2023). As Martin (2017) says, overcharging may often go unreported if workers get what they want, i.e., a well-paying job abroad.

This situation creates a high-impact opportunity for nonprofits to intervene and assist potential migrant workers in getting jobs abroad in an affordable, safe, and well-informed way. We believe that “bottom-up,” migrant-focused solutions may be especially effective in this environment where there is political support for change, but the on-the-ground reality is lagging. In section 3 of this report, we map out the barriers to better-quality labor migration and explore the range of activities nonprofits in this space can undertake.

The main nonprofit idea explored in this report is to create a “one-stop shop” service consisting of a digital platform – a website plus a mobile app – and light-touch personalized facilitation aimed to help potential migrants find suitable jobs, fulfill any migration-relevant requirements (obtaining visas, medical checks, skill certificates, etc.), and be informed about the pros & cons and the risks of migrating. This process currently typically relies on large networks of intermediaries who transmit information about job opportunities from large agencies to potential migrants living in local towns and villages and who then assist their clients with securing those jobs. We expect that this charity could have a positive impact in several different ways:

By digitizing much of the facilitation process and providing the service either for free or at cost (without a profit motive), this service could reduce the large inefficiencies in this market and reduce the intermediation fees paid by migrants by up to an order of magnitude (from over $1,000 to potentially less than $100).

By creating maximum transparency and not charging potential migrants upfront, the charity should be able to significantly reduce the rates of costly migration failure.

By making the service digital first and significantly reducing the fees, it could open the possibility of labor migration to less well-off and more rural candidates than the current costly in-person facilitation process.

It could help fill jobs that would otherwise remain vacant, thereby increasing the number of people who reap the benefits of labor migration.

Further value could be created by directly offering relevant services, such as skill certification, or by signposting users to verified good-value third-party services.

The focus of this report is primarily on temporary low- to mid-skilled voluntary and regular migration (also known as guest work), from low- and lower-middle-income countries to upper-middle-income countries. It does not focus on permanent migration, irregular migration, or refugee support, and it gives comparatively less attention to high-skilled migration and migration to high-income countries in Europe, North America, or East Asia – even though the charity could conceivably expand to serve these types of migrants as well.

The reasons for this focus are:

Temporary labor migration is a widespread form of migration. While we couldn’t find exact estimates, out of the 169 million international labor migrants worldwide (ILO, 2021), the majority may be temporary rather than permanent. For example, nearly all labor migration within Asia is temporary (ILO, 2007). Focusing on temporary migration is also more tractable due to generally higher political acceptability.

Most people experiencing poverty don’t have advanced degrees or specialist skills. While skilled laborers (such as nurses, doctors, and engineers) can obtain greater returns to migration when expressed in dollar terms (Maskus, 2023), low- and mid-skilled laborers are those who can gain the most from the point of view of welfare and poverty reduction.

Economic migration is receiving very little philanthropic attention despite the potentially large social impacts. This stands in contrast to work focused on irregular migration and forced displacement – the focus of a range of national and international organizations – and skilled migration, which is relatively better catered to by the private sector (although still arguably neglected).

Migrants traveling via legal channels with a confirmed job at the destination are less likely to suffer detrimental outcomes (like poverty, unemployment, or forced labor) than irregular migrants, and we are therefore more confident that this type of migration is net beneficial.

Migration to upper-middle and high-income countries in the Middle East and Southeast Asia is already prevalent, and the processes and barriers to impact are well understood (see section 3.1). In contrast, migration to high-income countries in Europe, North America, and East Asia is currently more limited, less well understood, and the process is often more complicated, requiring workers to speak the local language and be more highly skilled. That being said, migration to these countries – especially via counterfactually new pathways – could create especially large returns. We explore the possibility of the charity expanding into this space in section 3.4.

The focus on temporary labor migration is also in line with the priorities of governments, as well as intergovernmental organizations, such as the UN or the World Bank, all of whom have recently been creating new formal pathways for workers to get jobs abroad (based on our expert interviews).

3 Theories of change

3.1 Barriers

There is a complex set of barriers preventing potential migrant workers from getting good, fair jobs abroad and migrating safely at a low cost. These barriers must be simultaneously overcome for labor migration to be successful and generate greater social returns.

We can organize these barriers into multiple levels:

Personal barriers on the level of individual migrants

Lack of awareness of opportunities: Potential migrants may not be aware of existing opportunities matching their skills and preferences.

Lack of knowledge of how to navigate opportunities: International migration is a complex process, and most migrants need support with it, either from friends and family members or from dedicated organizations.

Misinformation about costs and potential earnings: To make good decisions, people need to know how much the process of migrating costs and how much they can expect to make at the destination. However, past studies have found evidence of misinformation: Migrants from Tonga to New Zealand expected to earn about 40% less than typical migrants actually earn (McKenzie et al., 2007) – likely resulting in a reduced supply of migrants – while people in Bangladesh typically overestimate earnings abroad, by as much as 50% (Ahmed & Bossavie, 2022) – often resulting in disappointment and indebtedness.

Limited awareness of the risks of working abroad: International migration carries a number of risks to one’s physical and emotional well-being. This is especially true in the case of low-skilled migration, which may expose migrants to hard working conditions and various forms of exploitation. However, awareness of such risks is low: some 60% of Bangladeshi migrants are never exposed to information about how to migrate safely (Bosssavie, 2023).

Uncertainty and fear: On top of incorrect information, potential migrants experience a high level of uncertainty: They may simply not know what it is like to live and work abroad and prefer the known over the unknown (McKenzie, 2023). Relatedly, fears of undesirable outcomes may keep people from migrating. These factors are likely more prominent in regions with currently low levels of migration where people can’t learn from the experiences of others in their communities.

Lack of necessary skills, such as language skills: Language skills often form a barrier to obtaining visas and foreign employment, even in lower-skilled jobs such as agriculture and hospitality. However, these are less of a concern in the destination countries we are considering (such as the Gulf countries), where the large numbers of migrant workers, even at managerial levels, allow people to work there without knowing the local language very well.

Lack of certifications for existing skills: Obtaining such certifications may be difficult or costly.

Lack of financial resources: Potential migrants need money upfront to pay for visas, upskilling, skill certification, travel, and any intermediation services that help them in the migration process.

Barriers related to local countries of origin

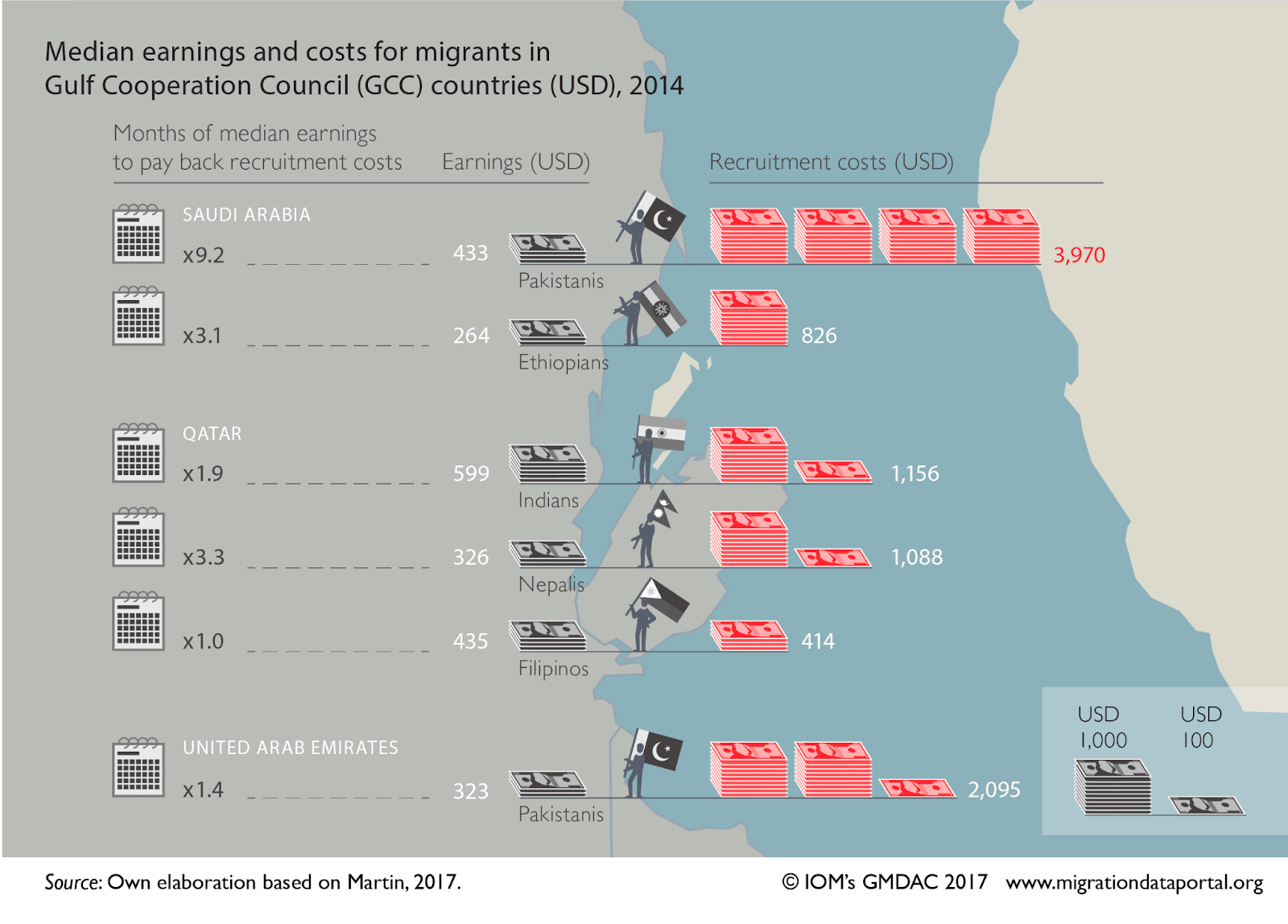

Expensive intermediaries: Many countries with large potential-migrant populations (such as India or Bangladesh) rely on large numbers of local intermediaries who offer services like help finding jobs and obtaining the necessary paperwork. These often long chains of intermediaries create an inefficient and expensive system. Typical recruitment costs range from around $1,000 in India, Ethiopia, and Nepal to over $3,000 in Bangladesh – equivalent to almost ten months of earnings at the destination (Migration Data Portal, 2021).

Fraud and exploitation: In some cases, intermediaries may be fraudulent or undertake various exploitative practices, which can result in failure to migrate and huge financial losses for the person and their families (Das et al., 2014).

Lacking or low-quality migration-related services: Some regions may not have a sufficient supply of quality services for migrants, such as language training or skill certification. In our conversation with the Labor Mobility Partnerships (LaMP), an NGO, we learned that healthcare workers from Kenya may need to travel to South Africa to obtain employer-recognized certificates.

Lack of financial services geared toward international migrant workers: International migrant workers often require borrowing money to finance skill acquisition or travel expenses, but there is a lack of financial organizations willing to provide them with credit.

Barriers related to destination-country employers

Finding workers: Employers may not know where to look for potential migrant workers and how to effectively advertise their jobs abroad (although this is somewhat less of a concern in well-established migration corridors).

Recognizing workers with relevant skills: Employers may struggle to recognize which potential workers have relevant skills and, therefore, be reluctant to hire them.

National/international barriers

Limited visa options: Many developed countries restrict the number of worker visas they issue or make it difficult for potential migrants to obtain them.

Global priorities of funders: Labour mobility has not been a major priority for international aid organizations. LaMP estimates that only 0.5% of private philanthropy goes toward the economic inclusion of people on the move, and only a fraction of this focuses on providing opportunities for potential migrants – as opposed to supporting refugees or actively deterring migration.

The importance of each of these barriers will vary substantially between different countries. For instance, countries with an extensive culture of labor migration (like Nepal) will experience different barriers (and enablers) than countries where international labor migration is currently more limited.

3.2 Potential charity activities to support international labor migration

There is a wide range of services that charities in this space can offer to increase labor migration rates and ensure that people can migrate safely and affordably and reap the benefits they expect to get from working abroad. In Figure 2 below, we map the needs of potential migrants (in grey) and show how they relate to potential charity activities/services (in yellow). The figure also displays several “enablers,” i.e., features that enable the usage of the yellow services. These include transparent information (about what services are needed and what exactly is being offered), recommendations for high-quality (third-party) services, and financial affordability, which can either be achieved by making the services low-cost or by offering financial products, such as loans or insurance.

The relative importance of each of these services will depend on the specific context in which the charity operates. Different countries of origin may be experiencing different gaps in service provision that act as the key barriers to migration – charities in this space will need to assess local needs and services that are already available to determine where they can be most effective. They may also choose to provide a combination of services, such as linking job boards with initial stages of recruitment or offering pre-departure training on top of language training and certification.

Figure 2: Barriers, services, and enablers needed for prospective migrants (in countries where visas and job opportunities are available).

While all of these services are important, we believe that transparent information provision paired with job boards and low-cost support with applications are especially promising. This is for several reasons:

Extensive evidence indicates that potential migrants lack access to high-quality information about how to get jobs abroad and how to migrate in a way that is safe and that maximizes one’s financial returns (se

Information also serves as an enabler of existing services. In many places, services such as language training or skill certification may already exist, but potential migrants may struggle to find them or identify high-quality providers (Bazzi et al., 2021). By providing recommendations for third-party services, the charity may help facilitate migration without providing these services directly.

While information is important, it alone may not be enough to attract people’s attention: What potential migrants look for are job opportunities and assistance with applying, rather than information per se (based on our expert interviews). As such, a charity is much more likely to gain users (and achieve impact) if it actively helps people get jobs abroad – and provides high-quality information at timely points along the process.

Information provision and support with the application process can be provided in a cheap, scalable way – especially if the charity uses a digital-first approach.

By directly helping people get jobs, the charity will have options for creating sustainable financing models. The experts we spoke with indicated that some past projects in the space of international labor migration failed because they couldn’t attract long-term funding. A charity that actively helps match migrants with jobs will have the option to charge a small fee for its services – either to the migrants or to the employers/employment agencies – thereby reducing its reliance on donor funding. We discuss this in more detail in section 7.

Experts we spoke with highlighted access to finance as a priority need. This is especially true for individuals intending to get higher-skilled jobs abroad, which may require expensive certificates and months-long language courses. However, for lower-skilled migrants, most expenses are spent on intermediary fees (see Figure 6 in section 4.2). As such, we believe it is more tractable and cost-effective to work on reducing these fees rather than providing loans to help cover them.

Note that the mapping above assumes that a lack of job opportunities or visas would not be a major barrier. This is unlikely to be the case: in fact, a promising avenue for a charity may be to focus on advocacy for increased numbers of work visas between specific countries of origin and destination. However, based on our conversation with Prof. Mushfiq Mobarak, we have deprioritized this option, for the following reasons:

The expansion of international migration corridors is already the focus of large international organizations, such as the World Bank and the Center for Global Development.

Reaching agreement between pairs of countries is a complex political task, and it is unlikely that it is where a new, small charity could make the most difference.

An arguably better way for a new charity to contribute to these efforts is to help strengthen the argument that international labor migration can be done safely and effectively.

A charity that focuses on the “supply” side of the migration issue can still achieve a significant impact. Firstly, by improving the “quality” of migration (reducing the costs and risks), and secondly, by helping to fill jobs that are currently harder to fill.

In the following section, we explore how exactly a charity focused on information provision could operate and how it would achieve social impact.

3.3 Theory of change of this charity

The key idea behind this potential charity is to create a semi-automated service consisting of a digital platform and one-on-one facilitation, aiming to reduce the many inefficiencies, information gaps, and exploitative practices that potential migrant workers in LMICs experience. There are multiple ways such a platform could be developed to address different kinds of migrant needs. Correspondingly, this charity may need to undertake a range of activities and may have several ways of achieving impact. The charity founders will need to engage in repeated strategic planning and re-evaluations to identify the highest-impact marginal activities.

In Figure 3 below, we explore these different theories of change in detail. The diagram highlights which elements of the theory of change we consider to be key for any charity in this space but also includes elements that we think are optional or secondary in importance.

Figure 3: Theory of change of the charity. Boxes with full outlines signify key activities, outputs, outcomes, and ways of achieving impact; dotted boxes highlight optional activities or secondary ways of achieving impact. See Appendix 1 for a simplified version.

Each numbered circle is associated with an assumption about the link between elements of the theory of change. We explore these assumptions below:

The charity can gather necessary information and organize it in a user-friendly format on a website or an app (likely): Creating a user-friendly app with high-quality information will be a key activity of the charity. This is not an easy task: it will require extensive web-based and in-person research paired with quality web/app development. However, we believe that this is a tractable challenge.

The charity can collect information and set up systems in such a way that the provided information is up to date (likely): A major challenge of creating a large service like this is ensuring that all of the information (e.g., about visa options, job opportunities, or government regulations) is up to date. Setting up such a system will require careful planning and may require a mixture of algorithmic solutions, in-country contractors, and user input. While challenging, this is also where major value can be created for the users.

It is possible to create a functional job board (highly likely): A job board can be created either by connecting directly with employers or by working with existing employment agents and third-party job boards. Unless there are local restrictions preventing a charity from advertising jobs, this should be a tractable task.

It will be possible to partner with employers and/or international organizations to create new job opportunities (medium uncertainty): We expect employers and international organizations in the labor migration space to be happy to collaborate with this charity. We are unsure whether this is likely to lead to the creation of new job opportunities or only better information about existing opportunities. Note also that new job opportunities are only possible between pairs of countries where the governments have agreed to allow temporary labor migration.

It is possible to partner with existing organizations (highly likely): Our expert interviews indicate a large willingness of different actors in this space to collaborate, either to increase their impact as nonprofits or to increase their revenues as businesses.

It is possible to assess the quality of third-party services (medium uncertainty): Creating a well-functioning rating and recommendation system may not be an easy task, but there are plenty of existing organizations (apps like Yelp, Trustpilot, etc.) that the charity could learn from.

It is possible to set up algorithms for personalized recommendations (highly likely): Setting up at least a simple recommendation system should be a tractable task for skilled software developers.

The charity will be able to provide other high-quality services at a low cost (medium uncertainty): We have not explored this question in detail. We believe that the provision of some services (such as skill certification or pre-departure training) should be feasible, though it may require significant additional effort and may not be as cost-effective as other activities of the charity.

The charity can set up a call center to provide extra support where needed (likely): In order to build trust and minimize risks, it may be necessary to set up a system through which users can receive personalized human support if needed, such as via a call center. While we have some concerns about the cost implications, we think that this would be a tractable activity for the charity.

Outreach and advertising activities can create user trust and lead to uptake of the service (key uncertainty): In many migrant-sending countries, the process of migration relies on a network of intermediation services provided in person by individuals trusted by potential migrants. Creating enough trust in a largely digital service without prior brand recognition may be a key challenge for the charity. The charity may initially have to invest heavily in various outreach and advertising activities to get early users on board. While we believe that this will require careful attention, we do not think that this is an intractable problem.

Online/over-the-phone support is sufficient for most users (medium uncertainty): Our model of this charity assumes that users of the platform will be able to successfully migrate using the information and functionality provided by the platform supported by personalized human assistance (via WhatsApp or phone calls). However, it is possible that some users will require assistance beyond this; for instance, being escorted to government offices issuing visas or having their paperwork reviewed. We have some uncertainty about the need for these in-person tasks, how often users may need them, and how easy or difficult it may be to delegate them to third parties.

The platforms will reduce the cost of migrating compared to counterfactual options (highly likely): By focusing on maximizing the value for the users, designing efficient systems, and not seeking to make a profit, it is highly likely that the charity will be able to reduce users’ cost of migrating, compared to their counterfactual options.

The platform will help reduce loss of money due to migration failure (highly likely): By providing transparent information about what jobs are available, how much they pay, and how to get them, the platform will very likely reduce the rates of migration failure and the associated loss of money.

The platform will help migrants get better jobs (likely): Depending on the exact activities of the charity, it may be able to help individuals who would have migrated anyway to get better jobs – jobs that better match their skills and preferences, that pay more, or where they are treated better.

The charity can discourage some people from migrating (likely): We find it likely the charity can discourage from migrating some people who aren’t a good fit for it. For instance, by providing transparent information on all the costs and benefits, those who would otherwise overestimate the financial returns may now decide against migrating.

Usage of the platform will lead to an increased number of migrants (medium uncertainty): Whether the charity would be able to create additional (“counterfactual”) migration depends on the saturation of the job market and on whether some jobs would otherwise go unfilled. Some experts we spoke with believed that markets in destinations such as the Gulf countries and Southeast Asia are saturated, and additional migration is, therefore, unlikely. In contrast, others indicated that some jobs still go unfilled, and a digital service with a wide reach and low fees may be able to help fill these vacancies. Overall, we are somewhat uncertain about the exact balance between these two arguments. (See also section 3.4 for additional considerations on this point.)

The platform helps workers generate greater returns to migrating (highly likely): If the charity manages to decrease the intermediary fees and rates of costly migration failure (and potentially increase the rate of migration and help people find better-matching jobs), it is very likely that it will increase migrants’ total financial benefit. See section 4.4 for evidence on this point.

Greater financial returns lead to more remittances (highly likely): Migrant workers who earn more are very likely to remit more; see section 4.4.

Greater incomes lead to improved welfare (highly likely): An extensive literature documents a close link between incomes and self-reported well-being. See, for example, Ortiz-Ospina and Roser (2013).

The charity will generate valuable information for CE and other actors (highly likely): International labor migration is a highly understudied field, with few large-scale academic and nonprofit projects underway. This organization could make a significant contribution to the knowledge base about what works to improve migration, thus supporting other future efforts in this space.

The above analysis focuses primarily on activities targeted at individuals who intend to migrate but haven’t done so yet. However, the charity could conceivably provide services that support the full life cycle of a migrant, from before they even consider migrating to support during migration and after return (Bossavie, 2023). We omit these from this report, as we don’t think their inclusion is critical for deciding in favor of or against this charity idea. However, we encourage potential future founders to think about such additional services they may be able to provide.

3.4 Potential expansions of this theory of change

The main path to impact assumed in the previous section is improving the quality of low- and mid-skilled international labor migration, by improving access to information, reducing fees migrants are asked to pay, and reducing the chance of migration failure. However, there are additional ways that this charity could achieve positive impact:

Helping higher-skilled workers to migrate

Increasing the amount of migration (to current destination countries)

Facilitating migration to novel, higher-income destinations

Allowing poorer people to migrate

These are generally less well-evidenced, or we are less confident in their feasibility, but they may be worth considering for the charity founders.

1. Helping higher-skilled workers to migrate

The charity could use much of its infrastructure built for supporting low- and mid-skilled workers to also support high-skilled workers to migrate. Based on our shallow review of the evidence and conversations with experts, we understand that high-skilled workers – such as engineers, IT staff, education workers, or healthcare workers – also face extensive information barriers that prevent them from migrating, such as information about available visa options or achievable job opportunities.

However, high-skilled workers may also face additional barriers not experienced by lower-skilled workers, such as needing to know the language of the destination country to a high level of proficiency, having their skills certified by an internationally recognized agency, or otherwise being able to demonstrate their skills to employers from a different country and cultural background. These additional barriers may necessitate additional charity activities. While these could be costly, they may still be cost-effective, as the returns to high-skilled migration can be especially high: In terms of benefit-to-cost ratios, skilled migration was actually identified as one of the “best investments for the SDGs” by the Copenhagen Consensus Center (Maskus, 2023).

Additionally, helping skilled workers migrate raises the risks of causing harm through brain drain. This is most concerning to us in the domain of healthcare, where the emigration of professionals may have significant negative consequences on care provided in the country of origin. However, this topic is a complex one, with experts disagreeing about the effects and their magnitudes. For instance, Clemens and McKenzie (2009) argue that physician emigration creates incentives for more people to locally train as physicians, thereby being net positive. But Bhargava et al. (2011) found that while emigration does induce more training, the magnitude of the effect doesn’t fully offset the loss due to migration. We do not have a strong view on this debate, but we highlight these considerations in case future founders wish to expand in this direction.

2. Increasing the amount of migration (to current destination countries)

We are uncertain about the amount of counterfactually additional migration that the basic charity model would create. On the one hand, multiple experts we spoke with indicated that migration to well-established destination countries (such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) or Qatar) is very saturated, with high awareness of this option by populations in the migrant-sending regions and a resulting high supply of potential workers. This would mean that any migrant who is assisted by this charity to get a job would displace another potential migrant, who then wouldn’t get the job. On the other hand, anecdotal evidence shared with us by Dr. Tutan Ahmed indicates that this is only true for low-skilled jobs, and that recruitment gets harder for mid-skilled jobs, many of which go unfilled. If this is the case, then this charity may be able to create additional migration – and thereby the large impact associated with migrating (see section 4.2.2 for evidence) – by following the basic theory of change outlined in the previous section. This uncertainty is reflected in section 7 where we model cost-effectiveness in two ways: assuming no additional migration and assuming that some migration is additional.

In summary, if the charity wants to be more confident that it is creating additional migration (without an offsetting effect), we recommend that it focuses more on finding candidates for more mid-skilled jobs (such as cooks, tailors, carpenters, truck drivers, car mechanics, etc.).

3. Allowing poorer people to migrate

A charity in this space may also be able to create impact by changing who migrates, without increasing the overall quantity of migration. Generally, the poorer a worker (and their family) is, the more they benefit from migrating. However, the current high cost of migration and the poor information environment (see sections 4.1 and 4.2) mean that international guest work is often out of reach for the migrant-sending countries’ poorer and more rural members. By reducing recruitment fees and improving access to information – as the main theory of change assumes – the charity may achieve this benefit automatically.

The charity may also try to actively recruit lower-income users in order to boost this path to impact. This may involve, for instance, conducting outreach activities in particularly poor regions of the target country, or by trying to target their online advertising at users with very low incomes.

4. Facilitating migration to novel, higher-income destinations

The highest-impact expansion option would likely be for the charity to send migrant workers to very high-income destinations, such as Western Europe, South Korea or Japan. Given the high typical wages in those countries the potential returns are very large. These migration pathways are currently not very well established, so much of this migration would likely be fully counterfactual.

While the potential returns are high, the barriers for workers are also higher. Unlike countries in the Persian Gulf or Southeast Asia, these destinations typically look for at least mid-skilled workers. Additionally, given that only a small proportion of employees at the destination firms will typically be of the same migrant background, these migrants will typically be required to learn the local language. Language training alone is estimated to cost around $2000 and requires 6-12 months of full-time study, which not only creates a high opportunity cost but also increases the risks of losing money in case of migration failure. As such, if the charity wanted to expand in this direction, it may need to provide additional services, such as help finding high-quality language schools and offering low-cost loans (or other financing solutions) to make these upfront expenses possible.

In contrast to existing destinations, additional work would be required to activate employer demand. Given that employers in those destination countries may have limited experience with advertising their jobs abroad or employing foreign workers, the charity would likely need to engage extensively with specific employers and support them in expanding their recruitment to the target LMICs.

Although we are excited about the migration opportunities to these destinations, the evidence base is currently too limited for us to confidently recommend this option. Various pilot projects are underway to test models of facilitation migration to very high-income countries (by organizations such as LaMP, Malengo, or Imagine Foundation), but few of these have been sustainably scaled up or rigorously studied and evaluated. We recommend that the charity founders stay in touch with organizations and researchers in this space and review their options for this form of expansion in several years, by which point the evidence base may have grown.

4 Quality of evidence

Judging whether this charity idea is worth recommending requires a chain of evidence and reasoning. We explore these in the following subsections: Section 4.1 examines the information aspect of this charity idea: whether potential migrants are currently well-informed or misinformed (section 4.1.1), and how good the current information channels are (section 4.1.2). Section 4.2 then explores the evidence that charities in this space can have a positive impact. First, section 4.2.1 focuses on the (avoidable) harms experienced by migrant workers; then, section 4.2.2 reviews the evidence on the potential financial benefits from temporary international labor migration; and section 4.2.3 briefly reviews the evidence on non-financial considerations related to migrant workers’ well-being. Lastly, section 4.3 provides evidence that a charity can achieve this.

Overall, international labor migration is an academically understudied field, with limited high-quality observational evidence and even less causal evidence of the impact of interventions. In fact, the renowned economist Lant Pritchett has called it “development’s missing agenda” (Harvard Center for International Development, 2018). Even where labor migration has been explored, it has often focused on dealing with migration that is already happening or on ways of discouraging irregular migration – as opposed to increasing or improving voluntary, legal and orderly migration.

Nevertheless, there is much that we can learn from existing data, and given the large effects that international migration can have on people, there is arguably less need for rigorously conducted trials for us to make the argument in favor (or against) the idea.

4.1 Evidence that people currently lack good-quality migration-related information

For this charity to have a counterfactual impact, it needs to (1) provide information to people that they don’t already know, and (2) provide information in a way that is more accessible or useful than information provided by other sources. There will surely be huge differences across countries, with some populations having bigger knowledge gaps and worse access to information. However, given that our evidence review suggests that such gaps exist even in countries with high migration rates and in high-income contexts, we believe that it is likely that these gaps are widespread, with this charity likely being additional in many different locations.

4.1.1 Evidence that people are under- or mis-informed

Much of the existing evidence on knowledge gaps comes from South Asian countries, many of which have a strong culture of labor migration. Studies suggest that potential migrants are often misinformed about the basic aspects of working abroad, such as how much they can earn. As shown in Figure 4 below, Bangladeshi migrants often expect to be able to earn significantly more than they end up earning. These misaligned expectations can result in them being willing to pay unreasonably high fees to intermediaries with the hope of quickly recouping their losses. They are also the leading reason for migrants’ disappointment at their destination and for returning home earlier than planned (Ahmed & Bossavie, 2022). The situation is similar for Nepalese and Pakistani migrants.

Figure 4: Wage levels expected before departure compared with wages actually earned overseas by temporary migrants from Bangladesh. (Ahmed & Bossavie, 2022, p. 14)

Some of these realities, however, may be highly country-dependent. In the case of Tongans migrating to New Zealand, McKenzie et al. (2007) found a large underestimation of potential earnings, by about 40% on average. In the context of Nigerians intending to migrate to Europe, Beber and Scacco (2022) also find evidence of underestimated earnings.

Potential migrants are also often under-informed about how to migrate safely. Bosssavie (2023) cites research indicating that some 60% of Bangladeshi migrants were never exposed to information about how to migrate safely, and of those who say they have learned about safety, 58% say that they got this information from their friends (rather than via any formal channels).

4.1.2 Evidence of deficiencies in existing information channels

While the reasons for this lack of information or misinformation are complex, there are reasons to believe that current channels are often insufficient or ineffective in providing accurate and up-to-date information to potential migrants.

In the South Asian region, networks of private agents and middlemen are the most common way for people to obtain information (conversation with Dr. Tutan Ahmed; Bosssavie, 2023). While these agents have a profit motive to connect potential migrants with real job opportunities and services, it may also be in their interest to systematically misrepresent information, such as understating costs and risks and exaggerating potential returns. It may also not be economical for them to operate in rural areas, thereby leaving much of the population with limited access to information (Bosssavie, 2023).

Intermediaries are a crucial part of the migration process. In many regions, essentially all migrant workers use intermediaries (e.g., 100% of the sample of Indian guest workers in Saudi Arabia, as observed by Naidu and colleagues, 2023). Inter- mediaries help aspiring migrants navigate complex immigration bureaucracies and address the many uncertainties prospective migrants face (Jones & Sha, 2020). They conduct various activities to facilitate migration, including helping broker visas, arranging birth certificates and passports, booking transportation, guiding, finding jobs and accommodation, connecting migrants to healthcare and medical tests, etc. They may also arrange training and assist in candidate selection.

The charity described in this report would try to reduce the need for in-person intermediaries. Instead, it would provide information for free in a digital format and scale up semi-automated ways of offering the above-described services at a low cost.

Governments sometimes step in to provide information to migrants and prepare them for working abroad. For instance, governments in the Philippines and Sri Lanka organize comprehensive pre-departure programs for all international migrant workers (Ahmed & Bossavie, 2022). In many other countries, however, such services are more limited. In Bangladesh, the government does provide some formal sources of information, but they are rather limited in their extent and quality (Bosssavie, 2023). In India, the government behaves more like a regulator of migration rather than a direct service provider, so its role is even more limited (conversation with Dr. Tutan Ahmed).

In some countries, information sharing is also being done by local NGOs. For instance, in Bangladesh, District Employment and Manpower Offices collaborate with local NGOs to share information on safe migration across Bangladesh. However, these NGOs tend to have limited capacity to run their programs at scale and struggle to reach rural populations (Bosssavie, 2023). BRAC, Bangladesh’s largest NGO, also provides extensive services to potential (as well as current and returning) migrants. Between 2006 and 2018, it provided 937,000 potential migrants with information on safe migration. However, to our knowledge, its programs also tend to be community-based, which – while being ideal for building trust and providing personalized support – likely limits the scale and ability to deliver fully up-to-date information.

The above-discussed channels – private, government-provided, and community-based nonprofits – could be supplemented, enhanced, or replaced by a high-quality web-based platform delivered by an impact-maximizing nonprofit. Given the high smartphone penetration rates in many developing countries (e.g., 71% in India; Statista, 2023), there is an opportunity to bring this information directly to users instantaneously and at no cost to them.

What do existing web-based services offer? While it was not feasible for us to do a comprehensive assessment of the current websites and online services, we have conducted a quick review of the websites that come up when searching the web for information on how to work abroad from the perspective of a worker in India (the top country in our geographic assessment). We found the following types of websites:

Websites of travel insurance companies

Websites focused on visa information (such as VisaGuide.world)

Recruitment agencies – see Table 1 below

Standalone articles on how to get jobs or how to migrate safely on websites that are not exclusively dedicated to migration

Government websites of the receiving-country governments that provide information on how to immigrate or obtain a visa to that specific country (these usually only come up when searching for specific destination countries).

Table 1: Large recruitment agencies (with an online presence) in India and the type of information and services they offer.

| Website | Type of organization | Information and services offered |

| Ambe International | A large employment agency and consultancy that has helped make over 350,000 placements since 1983. They have worked with unskilled, semi-skilled, and highly skilled workers in the oil & gas, construction, and other sectors globally. |

|

| Magic Billion | A company offering support with getting jobs abroad, including upskilling, assessment, financing, and helping with visa documentation. |

|

| G.Gheewala | An employment agency and consultancy in existence since 1978. It’s focus is both on low and semi-skilled jobs (construction, oil & gas, mining, manufacturing, hospitality, transportation, agriculture) and highly skilled jobs (e.g., healthcare and IT). |

|

| Kansas Overseas Careers | A large company (200+ employees) providing personalized guidance, legal advice, and interview training to help people study or work abroad. |

|

| Global Tree | A company that intends to be the one-stop shop to support Indians’ international career plans. They provide personalized advice and guidance on various ways of emigrating. |

|

While all of these websites are informative, we do find significant gaps:

Transparent and comprehensive information about the costs and returns to migrating – job boards often list the salaries people can be paid but don’t contain information on living costs, transportation costs, or the typical intermediation and training fees.

Information on safety – we generally found little information on safety aspects (while it may be provided later, it was not displayed prominently).

Information on who should and shouldn’t migrate – private services typically do not try to discourage customers from migrating, even though it may not be a good option for them.

Helping migrants decide what kinds of destinations or jobs are a good match for them – this is normally only offered to customers after a consultation.

Recommendations for third-party services – most companies either direct users to their own services or don’t offer any guidance on where else to go.

The services typically provide much of this information, but typically for a fee rather than in a free and transparent manner.

The experts we spoke with also agreed that a service like the one imagined in this report doesn’t currently exist (at least in India and Indonesia, which they have the most experience with). One reason may be that mobile and internet penetration has only recently gotten meaningfully high in these regions, so such digital services are yet underdeveloped (Prof. Samuel Bazzi). Another reason may be related to organizations’ business models: For-profit companies are not incentivized to provide information for free; nonprofit organizations may struggle with sustainability if they do not generate any revenue (Jason Wendle). This suggests that an appropriate model for this organization may be of a revenue-generating nonprofit: one that aims to maximize welfare (not profits) but can sustain itself by generating income and not being entirely dependent on donor money. We briefly explore this option in the Appendix 2.

In sum, we have found extensive opportunities that a nonprofit in this space could fill and that would likely provide significant value to potential migrants.

4.2 Evidence that work on temporary international labor migration can generate a positive impact

There are three main ways in which this charity may have a positive impact:

Increasing the number of people who migrate

Improving the “quality” of the migration

Changing who migrates to be those with more to gain (lower at-home incomes)

A charity may be able to create all three of these paths to impact simultaneously. However, we see this as a helpful way to analyze the quality of evidence and think about what the charity should focus on. The table below summarizes our views on the potential impact and tractability of these three paths to impact.

Table 2: Summary of main paths to impact.

| Path to impact | Primary mechanism of impact | Potential scale of impact | Evidence of tractability |

| (1) Increasing the number of migrants | Increasing wages of low-income individuals and their families | Very high – experts estimate millions of new migration opportunities could be created | Low – evidence exists from pilot projects, but we are not yet confident in the scalability and sustainability of their models |

| (2) Improving migration quality | Increasing average returns by decreasing costs | High – multiple countries suffer from problems affecting millions of people | Medium-high – extensive of evidence of the problems, more limited evidence of solutions |

| (3) Changing who migrates | Increasing the relative returns by decreasing the baseline salary | Low-medium | Uncertain – we have explored this option less so are uncertain about the state of the evidence |

In this report, we focus on improving the quality of migration. This is due to a combination of good-quality evidence on the problem and its potential solutions paired with a large scale of potential impact. Moreover, we believe this charity may naturally change who migrates (benefit (3)) by reducing the cost of migrating, and it may additionally be able to expand to focus on increasing the number of migrants (benefit (1)), as discussed in section 3.4.

4.2.1 Evidence that migrants currently experience harms

While the evidence is somewhat limited, we believe that there are good reasons to believe that this charity could improve the quality of migration and improve its returns for migrants and their families.

The first way this may be achieved is by lowering the costs associated with migrating. The largest fraction of these costs are due to fees paid to intermediaries and employment agents (see Figure 5). These fees can be extremely high, equaling years of at-home salaries and months of full-time salaries at the destination (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Intermediation costs for Bangladeshi migrants in 2018/2019, split by component. Intermediary costs consistently make up the majority of migration-associated expenses (Ahmed & Bosssavie, 2020, p. 51)

The reasons for such high fees are complex but seem to primarily be the result of:

The fact that the current situation relies on a time-intensive process whereby migrants receive a range of personalized services from intermediaries (such as assistance with finding job opportunities, handling visas, travel arrangement, insurance, etc.),

Asymmetry of information between potential migrants and intermediaries, allowing the well-informed intermediaries to extract excessive value from under-informed migrants, and

An oversupply of workers, which puts intermediaries in a position of power (Bosssavie, 2023).

By creating an easy-to-use web platform that potential migrants can use directly and for free, many of these middlemen can be removed from the process, increasing efficiency and reducing costs (supported by our conversation with Dr. Tutan Ahmed).

Figure 6: The costs of migrating for selected pairs of countries (Migration Data Portal, 2021).

There are reasons to believe reducing these fees is possible. As shown in Figure 6, these costs vary widely across migrant-sending countries. Filipinos, whose labor migration is managed by the government, pay about three times less than Indians, where the migration market is much less regulated. In the example of Bangladesh, a visa lottery that allowed some workers to migrate to Malaysia under a government-managed scheme lowered fees from the typical USD$3,000-$4,000 to around $400 (Mobarak et al., 2023). This points to inefficiencies and overcharging in these countries that an impact-maximizing charity could tackle.

Another way a charity could increase the quality of migration is by reducing the likelihood of migration failure and its associated costs. Bossavie (2023) says: “The current lack of formal information sources about migration opportunities in Bangladesh [...] leads to frequent migration failures. One-third of migration attempts from Bangladesh currently end in failure.” (pp. 15-16) On top of misinformation, failure may simply be the result of changing preferences or situational factors of the potential migrant (based on our conversation with Dr. Tutan Ahmed). In such cases, however, the typical practice in countries like India and Bangladesh is that the intermediaries keep the fees paid to them instead of returning them to the customer.

Such financial losses can be substantial. The medium and average losses associated with failure to migrate from Bangladesh were $250 and $818, respectively (Das et al., 2014). In the context of West Bengal, data collected by Dr. Tutan Ahmed indicates an average loss of $580. Given average monthly household incomes of $250-$300, these are very large expenses, often putting families significantly in debt.

Again, an impact-maximizing – rather than a profit-maximizing – organization could likely significantly reduce these costs, either by not charging the user at all or by setting fees without any margins, and returning fees in cases of migration failure. By providing transparent information about the costs, returns, and risks associated with migration, the charity may also discourage from migrating those who wouldn’t benefit from it (as was observed in the Safe Migration for Bangladeshi Workers pilot program run by BRAC in Bangladesh; Das et al., 2014).

Relatedly, extensive inefficiencies likely exist in information-poor environments regarding the choice of other migration-related services – such as language training or skill certification – where uninformed customers may inadvertently use poor-quality, high-cost services. If a charity could develop a reliable recommendation system for third-party services, it could likely save users non-trivial sums of money. Two experimental studies support this contention:

Bazzi et al. (2021) ran a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in Indonesia, in which individuals interested in migrating abroad were given information about the quality of intermediaries. This helped participants get better pre-departure training and have better experiences abroad. The authors say: “our results suggest that prospective international migrants in Indonesia face substantial information frictions when selecting placement services” (p. 23) and “quality disclosure interventions could be particularly effective in settings like ours where intermediaries are numerous and the market is fragmented.” (p. 1)

Fernando and Singh (2023) performed an observational study examining the effects of publicly revealing the results of an intermediary rating program in Sri Lanka. They found that the nationwide disclosure program actually improved the market: It induced intermediaries to improve placement quality by better screening employment opportunities abroad. This suggests that, if the charity managed to achieve meaningful scale, such third-party rating mechanisms could not only improve migrants’ choices but also improve the quality of third-party services that are being offered.

There are also non-financial ways in which this charity could increase migration quality. One of these is migrant safety. Temporary labor migrants can suffer from issues such as forced labor, having their passports withheld by employers, delayed wage payments, and other forms of abuse and discrimination (Reza et al., 2019). A charity focused on maximizing migrant welfare (as opposed to its own profits) could implement systems to collect information on such abuses and discourage future migrants from taking up jobs with problematic employers. One way to do this would be to allow current migrants to fill out surveys or upload video testimonials about their migration and job experience for future migrants to see; this is currently being trialed on the platform developed by Dr. Tutan Ahmed for migrants from India. While migrants from LMICs are often willing to undertake a significant risk of harm, it is highly likely that they would switch to safer alternatives if the charity provides them with such options (based on our conversation with LaMP).

By improving access to information and decreasing the costs of migrating, the charity may achieve additional impact by changing who migrates (benefit (3) in Table 2 above). Migrants from lower-income families stand to earn more from the same job abroad, since their relative wage increase is higher. At present, however, migrant workers typically come from families with close connections to past migrants, and only those who can afford the high upfront fees can reap the benefits of working abroad. Clemens (2020) found that people preparing to migrate out of low-income countries typically have incomes 30% higher than the average. In Bangladesh, only 2% of the households in the bottom consumption quintile have one or more migrating family members, compared to over 15% in the top quintile (i.e., a sevenfold difference; Ahmed & Bosssavie, 2020). In Nepal, where costs are lower, the effect of income is weaker, with the respective figures being 12% and 26% (i.e., a roughly twofold difference).

4.2.2. Evidence that temporary international labor migration (compared to no migration) has a positive effect on earnings

The evidence on the causal impacts of international labor migration is generally limited. However, we find sufficient reasons to believe they are substantial. The main benefits we consider in this section are the financial returns to migrants and their families and the associated well-being gains. The primary risks that we consider are those of financial loss and of being mistreated at the destination. There is a range of additional positive and negative considerations that we don’t have space to address in this report. These include the effects on the economies of sending and receiving countries, concerns around “brain drain,” effects of return migration, the value of information (to CE and the broader migration-research community), non-utilitarian considerations (such as agency, equality of opportunities, dignity etc.), and effects that orderly labor migration may have on the acceptability of international migration more broadly. Overall, we believe these are less important than the primary effects and more likely to be net positive than negative.

Estimating the causal effects of migration is challenging since migration is difficult to randomize, and observational estimates suffer from severe selection effects. Past studies have employed methodologies such as matching, instrumental variables, regression discontinuity designs, and panel data techniques (see Mobarak et al., 2023 for references).

Here, we will only review randomized experiments and studies that exploited natural experiments, arguably the most robust non-experimental method. We are only aware of three such studies. One is an RCT and two studied the effects of visa lotteries (quasi-experimentally). This gives them a clear causal identification strategy, with the downside that they cannot isolate the effect of migrating for work per se but only the effect of migrating for work under the visa RCT/visa-lottery program. The winners of one of the programs also received government-provided intermediation services that losers weren’t eligible for. Nevertheless, these are the best empirical estimates available.

All three of these studies find large financial returns for the migrant and their close family members:

McKenzie et al. (2010) studied the effects of a visa lottery that allowed some Tongans to migrate for work to New Zealand. This program allowed 250 randomly selected individuals – and their nuclear families – to permanently relocate to New Zealand. The authors found that migration in this context led to a 263% gain in income (in the first year after migration and similarly afterward), and that the nuclear family benefitted similarly.

Mobarak et al. (2023) studied the effects of a visa lottery that allowed some 30,000 Bangladeshi individuals (chosen at random from over a million applicants) to migrate to Malaysia for agricultural work, under a government-managed program. This program only allowed workers themselves to migrate, with their nuclear families staying back home. The study found large positive returns: The families of those who won the lottery and decided to migrate experienced a 109% increase in their household incomes (compared to those who lost). Both the migrants themselves and their families benefited, the latter via a large increase in income from remittances.

Naidu et al. (2023) ran an RCT in which one group of participants was randomly offered the option to migrate for work from India to the United Arab Emirates (UAE). They found that workers typically doubled their total net compensation (after subtracting migration-related expenses).

Out of these three studies, the latter two are more relevant to the idea explored in this report, as they study the effects of temporary migration of workers unaccompanied by their family members, which is the predominant mode of international labor migration. Both of these found a rough doubling of household incomes – which can be transformative for families experiencing poverty.

4.2.3 Well-being effects of international labor migration

Financial returns are the primary motivation for people to migrate internationally under temporary work visas. However, they should not be the only consideration for organizations working in this space. Whether or not this form of migration is net beneficial for people’s welfare will depend also on non-financial factors, the key one of which is the experienced well-being of migrants during their time abroad.

Temporary migrant workers are exposed to a high risk of exploitation and harm, owing to the fact that their permit to stay is typically tied to their jobs and that they often need to work for several months just to repay the debt they took on in order to migrate. While these risks exist everywhere, the situation in the countries of the Persian Gulf – the top destination for many low-skilled migrant workers – is especially concerning. Numerous reports over the years have reported on the abuses these workers experience, including long working hours, poor housing conditions, confiscation of passports, limited food allowances, and insufficient workplace safety (e.g. Sherman, 2022). They may also have to endure racism and xenophobia from the local population. Ahmed and Bossavie (2022) report that about half of Nepali migrants in Qatar report violations of their rights, with the commonest issues being prolonged exposure to extreme heat, inability to change employers, and withholding of travel documents. Similar findings were also common in the literature review by Reza et al. (2018) on Asian migrant workers.

Experimental evidence supports the concern that workers at destination suffer negative well-being effects. In the experiment with Indian construction workers by Naidu et al. (2023) described in the previous section, the authors found that roughly 50% of participants in the treatment group did not take up the offer to go to the UAE and instead stayed in India, an observation which the authors explain by an expectation of disutility at destination (“the jobs in the UAE are particularly unattractive relative to jobs in India,” p. 2). Those who did migrate reported significant falls in their well-being, driven by primarily by increases in physical pain, effort, and heat, and, to a smaller extent, by non-significant increases in loneliness, stress, and anger. Overall, though, the well-being decrease was modest, around 0.16 standard deviations (on a composite measure of well-being).

It may, however, be somewhat misleading to look at the well-being of these migrants at the destination, without the broader context of their pre- and post-migration quality of life. In fact, many migrants come from families at risk of severe poverty and may be experiencing comparable risks to their well-being in their home countries.

One way to examine this question is to ask whether these migrants are experiencing worse conditions than they expected and whether third parties with better knowledge should discourage or try to eliminate it – what some authors call a “repugnant transaction.” This is what Clemens (2018) did in his analysis of data from a natural experiment of Indian construction works in the UAE, who either did or didn’t get a quasi-randomly visa, depending on their application’s timing.