Summary:

If you

Have a wide moral circle that includes non human animals and

Have a low or zero moral discount rate

Then the discovery of alien life should radically change your views on existential risk.

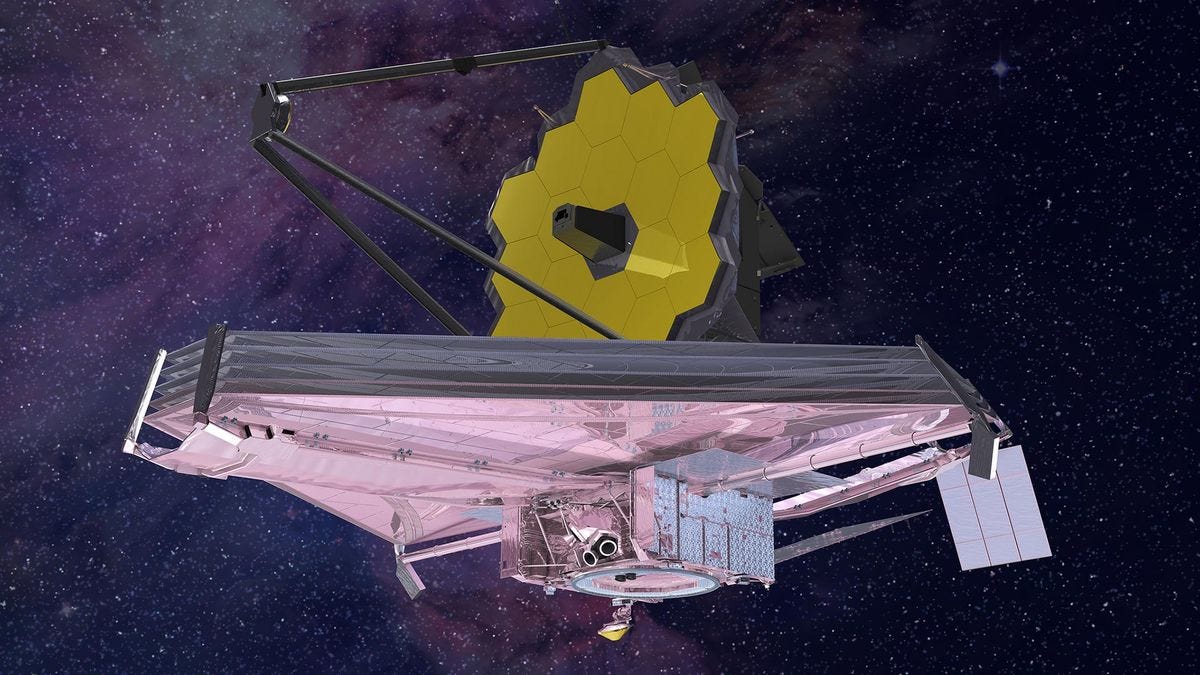

A grad student plops down in front of their computer where their code has been running for the past few hours. After several months of waiting, she had finally secured time on the James Webb Space Telescope to observe a freshly discovered exoplanet: Proxima Centauri D.

“That’s strange.” Her eyes dart over the results. Proxima D’s short 5 day orbit meant that she could get observations of both sides of the tidally locked planet. But the brightness of each side doesn’t vary nearly as much as it should. The dark side is gleaming with light.

Northern Italy at night

The Argument

This argument requires a few assumptions.

Strong evidence of intelligent alien life on a nearby planet

Future moral value is not inherently less important than present moral value

Many types of beings contain moral value including nonhuman animals and aliens

I will call people who have a Singer-style wide moral circle and a Parfit-style concern for the long term future “Longtermist EAs.” Given these assumptions, lets examine the basic argument given by Longtermist EAs for why existential risks should be a primary concern.

Start with assumption 2. The lives of future human beings are not inherently less important than the lives of present ones. Should Cleopatra eat an ice cream that causes a million deaths today?

Then consider that humanity may last for a very long time, or may be able to greatly increase the amount of moral value it sustains, or both.

Therefore, the vast majority of moral value in the universe lies along these possible future paths where humanity does manage to last for a long time and support a lot of moral value.

Existential risks make it less likely or impossible to end up on these paths so they are extremely costly and important to avoid.

But now introduce assumptions 1 and 3 and the argument falls apart. The link between the second and third points is broken when we discovery another morally valuable species which also has a chance to settle the galaxy.

Discovering aliens nearby means that there are likely billions of planetary civilizations in our galaxy. If, like Singer, you believe that alien life is morally valuable, then humanity’s future is unimportant to the sum total of moral value in the universe. If we are destroyed by an existential catastrophe, another civilization will fill the vacuum. If humanity did manage to preserve itself and expand, most of the gains would be zero-sum; won at the expense of another civilization that might have taken our place. Most of the arguments for caring about human existential risk implicitly assume a morally empty universe if we do not survive. But if we discover alien life nearby, this assumption is probably wrong and humanity’s value-over-replacement goes way down.

Holding future and alien life to be morally valuable means that, on the discovery of alien life, humanity’s future becomes a vanishingly small part of the morally valuable universe. In this situation, Longtermism ceases to be action relevant. It might be true that certain paths into far future contain the vast majority of moral value but if there are lots of morally valuable aliens out there, the universe is just as likely to end up one of these paths whether humans are around or not so Longtermism doesn’t help us decide what to do. We must either impartially hope that humans get to be the ones tiling the universe or go back to considering the nearer term effects of our actions as more important.

Consider Parfit’s classic thought experiment:

Option A: Peace

Option B: Nuclear war that kills 99% of human beings

Option C: Nuclear war that kills 100% of humanity

He claims that the difference between C and B is greater than between B and A. The idea being that option C represents a destruction of 100% of present day humanity and all future value. But if we’re confident that future value will be fulfilled by aliens whether we destroy ourselves or not then there isn’t much of a jump between B and C. When there’s something else to take our place, there’s little long-run difference between any of the three options so the upfront 99 > 1 wins out.

Many of the important insights of Longtermism remain the same even after this change of perspective. We still underinvest in cultivating long term benefits and avoiding long term costs, even if these costs and benefits won’t compound for a billion years. There are other important differences, however.

The most important practical difference that the discovery of alien life would make to EA Longermist prescriptions is volatility preference. When the universe is morally empty except for humans, the cost of human extinction is much higher than the benefit of human flourishing, so it’s often worth giving up some expected value for lower volatility. Nick Bostrom encapsulates this idea in the Maxipok rule.

Maximize the probability of an okay outcome, where an “okay outcome” is any outcome that avoids existential disaster.

Since morally valuable aliens flatten out the non-linearity between catastrophe and extinction, EA Longermists must be much more open to high volatility strategies after the discovery of alien life. So they don’t want to Maxipok, they want to maximize good ol’ expected value. This makes things like AI and biotechnology which seem capable of both destroying us or bringing techno-utopia a lot better. In comparison, something like climate change which, in the no-aliens world, is bad but not nearly as bad as AI or bio-risk because it has low risk of complete extinction, looks worse than it used to.

The discovery of alien life would therefore bring EA Longtermism closer to the progress studies/Stubborn Attachments view. Avoiding collapse is almost as important as avoiding extinction, compounding benefits like economic growth and technological progress are the highest leverage ways to improve the future, not decreasing existential risks at all costs, and there is room for ‘moral side constraints’ because existential risks no longer impose arbitrarily large utilitarian costs.

Examining and Relaxing Assumptions

Singer

Probably the easiest assumption to drop is the third one which claims that alien life is morally valuable. Humans find it pretty easy to treat even other members of their species as morally worthless, let alone other animals. It would be difficult to convince most people that alien life is morally valuable, although E.T managed it. Many find it intuitive to favor outcomes that benefit homo sapiens even if they come at the expense of other animals and aliens. This bias would make preserving humanity’s long and large future important even if the universe would be filled with other types of moral value without us.

If you support including cows, chickens, octopi, and shrimp in our wide and growing moral circle, then it seems difficult to exclude advanced alien life without resorting to ‘planetism.’ It might be that humans somehow produce more moral value per unit energy than other forms of life which would be a less arbitrary reason to favor our success over aliens. Even after discovering the existence of alien life, however, we would not have nearly enough data to expect anything other than humans being close to average in this respect.

Aliens

The first assumption of observing alien civilization is sufficient but not entirely necessary for the same result. Observation of any alien life, even simple single cellular organisms, on a nearby planet greatly increases our best guess at the rate of formation of intelligent and morally valuable life in our galaxy, thus decreasing humanity’s importance in the overall moral value of the universe.

Longtermism and wide moral circles may dilute existential risk worries even on earth alone. If humans go extinct, what are the chances that some other animal, perhaps another primate or the octopus, will fill our empty niche? Even if it takes 10 million years, it all rounds out in the grand scheme which Longtermism says is most important.

Robin Hanson’s Grabby Aliens theory implies that the very absence of aliens from our observation combined with our early appearance in the history of the universe is evidence that many alien civilizations will soon fill the universe. The argument goes like this:

Human earliness in the universe needs explaining. Earth is 13.8 billion years old, but the average start lives for 5 trillion years. Advanced life is the result of several unlikely events in a row so it’s much more likely for it to arise later on the timeline than earlier.

One way to explain this is if some force prevents advanced life from arising later on the timeline. If alien civilizations settle the universe, they would prevent other advanced civilizations from arising. So the only time we could arise is strangely early on before the universe is filled with other life.

The fact that we do not yet see any of these galaxy settling civilizations implies that they must expand very quickly so the time between seeing their light and being conquered is always low.

The argument goes much deeper, but if you buy these conclusions along with Longtermism and a wide moral circle then humanity’s future barely matters even if we don’t find cities on Proxima D.

Big If True

The base rate of formation of intelligent or morally valuable life on earth and in the universe is an essential but unknown parameter for EA Longtermist philosophy. Longtermism currently assumes that this rate is very low which is fair given the lack of evidence. If we find evidence that this rate is higher, then wide moral circle Longtermists should shift their efforts from shielding humanity from as much existential risk as possible, to maximizing expected value by taking higher volatility paths into the future.

While Grabby Aliens considerations may make our cosmic endowment much smaller than if the universe was empty (and I’d be interested in some quantitative estimates about that (related)) I think your conclusion above is very likely still false.[1]

The difference between C and B is still much greater than the difference between B and A. To see why, consider that the amount of value that humanity could create in our solar system (let alone in whatever volume of space in our galaxy or galactic neighborhood we could reach before we encounter other grabby aliens) in the near future in a post-AGI world completely dwarfs the amount of value we are creating each year on Earth currently.

[1] Technically you said “if we’re confident that future value will be fulfilled by aliens whether we destroy ourselves or not”, but that’s just begging the question, so I replied as if you had written “If we’re confident there are aliens only a few light-years away (with values roughly matching ours)” in that place instead.

You are right but we aren’t comparing extinction risk reduction to doing nothing, we are comparing it to other interventions such as s-risk reduction. If the value propositions are sufficiently close, this is insanely relevant as this could reduce extinction risk value by an order of magnitude or more, depending on your priors of grabby alien formation.

I think humans are probably more likely in expectation than aliens to generate high value as EAs understand it, simply because our idea of what “high value” is, is well, a human idea of it.

This seems like a strange viewpoint. If value is something about which one can make ‘truthy’ and ‘falsey’ - or something that we converge to given enough time and intelligent thought if you prefer—then it’s akin to maths and aliens would be a priori as likely to ‘discover’ it as we are. If it’s arbitrary, then longtermism has no philosophical justification, beyond the contingent caprices of people who like to imagine a universe filled with life.

Also if it’s arbitrary, then over billions of years even human-only descendants would be very unlikely to stick with anything resembling our current values.

Yes. See also Yudkowsky’s novella Three World’s Collide for an illustration of why finding aliens could be very bad from our perspective.

Existential risk from AI is not just existential risk to Earth. It is existential risk to our entire future light cone, including all the aliens in it! A misaligned superintelligent AI would not stop at paperclipping the Earth.

Although I guess maybe aliens could be filed under ‘miracle outs’ for our current predicament with AI x-risk.

Maxwell—this is an interesting and provocative argument that I haven’t seen before (although I’d be slightly surprised if nobody else has made similar arguments before). I think it’s worth taking seriously.

I think this is analogous to arguments like

If other potential parents are going to have kids anyway, why should I have kids that pass along my particular genes and family traditions?

If other universities are going to keep teaching and doing research, why should I worry about whether my particular university lasts?

If dominant languages (such as English, Mandarin, and Hindi) persist, and allow easier global communication, why should we worry about whether rarer languages like French, Arabic, or Bengali persist?

If other nation-states, cultures, and civilizations are likely to flourish anyway, why should I worry the fate of my particular nation-state, culture, or civilization?

If other organic life-forms on Earth are likely to evolve high intelligence and technological civilizations, sooner or later, why should we worry about what happens to humanity?

We have strong gut-level intuitions that our particular legacy matters—whether genetic, cultural, linguistic, civilizational, or species-level. But does our particular legacy matter, or is this just an evolved self-deception to motivate parenting, tribalism, and speciesism?

At the level of overall quantity and quality of sentience, if might not matter that much whether humanity colonizes the galaxy (or light-cone), or whether some other (set of) intelligent species does.

However, I think one could make an argument that a diversity of genes, languages, civilizations, and space-faring species yields greater resilience, adaptability, complexity, and interest than a galactic monoculture would.

Also, it’s not obvious that ‘everything that rises must converge’, in terms of the specific details of how intelligent, sentient life experiences the universe. Maybe all intelligent life converges onto similar kinds of sentience. But maybe there’s actually some divergence of sentient experience, such that our descendants (whatever forms they take) will have some qualitatively unique kinds of experiences that other intelligent species would not—and vice-versa. Given how evolution works, there may be a fair amount of overlap in psychology across extra-terrestrial intelligence (a point we’ve addressed in this paper) -- but the overlap may not be high enough that we should consider ourselves entirely replaceable.

I can imagine counter-arguments to this view. Maybe the galaxy would be better off colonized by a unified, efficient, low-conflict Borg civilization, or a sentient version of what Iain M. Banks called an ‘Aggressive Hegemonizing Swam’. With a higher diversity of intelligent life-forms comes a higher likelihood of potentially catastrophic conflict.

I guess the key question is whether we think humanity, with all of our distinctive quirks, has something unique to contribute to the richness of a galactic meta-civilization—or whether whatever we evolve into would do more harm than good, if other smart ETIs already exist.

Thank you for reading and for your insightful reply!

I think you’ve correctly pointed out one of the cruxes of the argument: That humans have average “quality of sentience” as you put it. In your analogous examples (except for the last one), we have a lot of evidence to compare things too. We can say with relative confidence where our genetic line or academic research stands in relation to what might replace it because we can measure what average genes or research is like.

So far, we don’t have this ability for alien life. If we start updating our estimation of the number of alien life forms in our galaxy, their “moral characteristics,” whatever that might mean, will be very important for the reasons you point out.

Maxwell—yep, that makes sense. Counterfactual comparisons are much easier when comparing relatively known optinos, e.g. ‘Here’s what humans are like, as sentient, sapient, moral beings’ vs. ‘Here’s what racoons could evolve into, in 10 million years, as sentient, sapient, moral beings’.

In some ways it seems much, much harder to predict what ETIs might be like, compared to us. However, the paper I linked (here ) argues that some of the evolutionary principles might be similar enough that we can make some reasonable guesses.

However, that only applies to the base-level, naturally evolved ETIs. Once they start self-selecting, self-engineering, and building AIs, those might deviate quite dramatically from the naturally evolved instincts and abilities that we can predict just from evolutionary principles, game theory, signaling theory, foraging theory, etc.

Check out this post. My views from then have slightly shifted (the numbers stay roughly the same), towards:

If Earth-based life is the only intelligent life that will ever emerge, then humans + other earth life going extinct makes the EV of the future basically 0, aside from non-human Earth-based life optimizing the universe, which would probably be less than 10% of non-extinct-human EV, due to the fact that

Humans being dead updates us towards other stuff eventually going extincts

Many things have to go right for a species to evolve pro-social tendencies in the way humans did, meaning it might not happen before the Earth becomes uninhabitable

This implies we should worry much more about X-Risks to all of Earth life (misaligned AI, nanotech) per unit of probablity than X risks to just humanity, due to the fact that all of Earth life dying would mean that the universe is permanently sterilized of value, while some other species picking up the torch would preserve some possibility of universe optimization, especially in worlds where CEV is very consistent across Earth life

If Earth-based life is not the only intelligent life that will ever emerge, then the stakes become much lower because we’ll only get our allotted bubble anyways, meaning that

If humans go extinct, then some alien species will eventually grab our part of space

Then the EV of the universe (that we can affect) is roughly bounded by how much big our bubble is (even including trade, becasue the most sensible portion of a trade deal is proportional to bubble size), which is probably on the scale of tens of thousands to billions of light-years(?) wide, bounding our portion of the universe to probably less than 1% of the non-alien scenario

This implies that we should care roughly equally about human-bounded and Earth-bounded X-risks per unit of probability, as there probably wouldn’t be time for another Earth species to pick up the torch between the time humans go extinct and the time Earth makes contact with aliens (at which point it’s game over)

Interesting post, which I would summarise as saying “if there are aliens, then preventing x-risk is not so important”. That can’t be right, because things like AI could kill aliens. And even if true, the applicability of this idea would be limited from the fact that aliens are at best even odds of existing.

But this line of argument could imply that utilitarian LTists should be happy to search for aliens. The utilitarian LTist would say “aliens might kill humanity, but that only happens in the world where aliens are already thriving, in which case them killing humanity would not constitute a risk to the future of flourishing life.” Obviously, it’s only a pretty strongly bullet-biting utilitarian who would endorse this, but I do think it would convince some people who currently oppose SETI for bad reasons.

I do not believe this. We may care about the aliens’ experiences, but this does not guarantee that they have values similar to ours (e.g. they may have different opinions on whether it’s acceptable to torture their children). Secondarily, there is no guarantee that they’ll have solved AI alignment, or similar issues. This means it’s nontrivially likely that SETI-signals/hacks are AI generated.

It seems like you’re raising two mostly unrelated issues. One is whether the SETI signals might be unconscious. This which would matter to utilitarians, although if signals are coming from aliens, then maybe all value is already lost. The other is the values of the aliens. One could then ask—why expect them to be better, or worse than our own?

For example, it seems more likely that human values will converge to something that my future self will endorse than that arbitrarily evolved aliens will. Thus, all else equal, I expect typical (after reflection and coherency) humans to have better values, by future me’s lights, than randomly selected aliens.

Sure, that’s why I said bullet-biting utilitarians.

I don’t get this intuition. If you have significant sympathies towards (e.g.) hedonic utilitarianism as part of your moral parliament (which I currently do), you probably should still think that humans and our endorsed successors are more likely to converge to hedonic utilitarianism than arbitrarily evolved aliens do.

(I might be missing something obvious however)

It depends why you have those sympathies. If you think they just formed because you find them aesthetically pleasing, then sure. If you think there’s some underlying logic to them (which I do, and I would venture a decent fraction of utilitarians do) then why wouldn’t you expect intelligent aliens to uncover the same logic?

I think I have those sympathies because I’m an evolved being and this is a contigent fact at least of a) me being evolved and b) being socially evolved. I think it’s also possible that there are details very specific to being a primate/human/WEIRD human specifically that’s relevant to utilitarianism, though I currently don’t think this is the most likely hypothesis[1].

I think I understand this argument. The claim is that if moral realism is true, and utilitarianism is correct under moral realism, then aliens will independently converge to utilitarianism.

If I understand the argument correctly, it’s the type of argument that makes sense syllogistically, but quickly falls apart probabilistically. Even if you assign only a 20% probability that utilitarianism is contingently human, this is all-else-equal enough to favor a human future, or the future of our endorsed descendants.

Now “all-else-equal” may not be true. But to argue that, you’d probably need to advance a position that somehow aliens are more likely than humans to discover the moral truths of utilitarianism (assuming moral realism is true), or that aliens are more or equally likely than humans to contingently favor your preferred branch of consequentialist morality.

[1] eg I’d think it’s more likely than not that sufficiently smart rats or elephants will identify with something akin to utilitarianism. Obviously not something I could have any significant confidence in.

This seems much too strong a claim if it’s supposed to be action-relevantly significant to whether we support SETI or decide whether to focus on existential risk. There are countless factors that might persuade EAs to support or oppose such programs—a belief in moral convergence should update you somewhat towards support (moral realism isn’t necessary); a belief in nonconvergence would therefore do the opposite—and the proportionate credences are going to matter.

I agree that convergence-in-the-sense-of-all-spacefaring-aliens-will-converge is more relevant here than realism.

“and the proportionate credences are going to matter.” I don’t think they do under realistic ranges in credences, in the same way that I don’t think there are many actions that are decision-guidingly different if you have a 20% vs 80% risk this century of AI doom. I agree that if you have very high confidence in a specific proposition (say 100:1 or 1000:1 or higher, maybe?) this might be enough to confidently swing you to a particular position.

I don’t have a model on hand though, just fairly simple numerical intuitions.

Hi I’ve posted this argument a few times as comments to other posts if people want to check out my work. I call it “Alien Counterfactuals” or “the civilization diceroll”.

Formalization of the argument

Comment on “the future might not be so great”—bullet point 3

Why I disagree with Scott Alexander about longtermism vs X-risk

Also the CLR has a lot of tangential work to this.

There is a good chance that Aliens already have known the position of us as intelligent life from the first three atomic bombs detonating at the end of WWII. It signaled our position. But they came in stealth as we were considered armed and dangerous. But this is not the end of the story. They have place us in a suspention where we are being judged as we speak. For this they have placed a lie over us but we cannot see it. Unless you look for it. In the Alien Assessment you can find a method to check for yourself that you actually are a simulation: Alien Assessment and proving of this Simulation.

What if

the moral (m) power of a longtermist (l) m. Worldwide civilisation is a log. / exp of expected v. view.

AI are included in the circle and learn by data.

Most alien civilisations that sustain long enough is a version of 1.

The civilisation in 1 result from the non intervention of 3.

Overtime a fraction however maximises expected value instead.

…. A lot of questions. Thank you!