This short research summary briefly highlights the major results of a new publication on the scientific evidence for insect pain in Advances in Insect Physiology by Gibbons et al. (2022). This EA Forum post was prepared by Meghan Barrett, Lars Chittka, Andrew Crump, Matilda Gibbons, and Sajedeh Sarlak.

The 75-page publication summarizes over 350 scientific studies to assess the scientific evidence for pain across six orders of insects at, minimally, two developmental time points (juvenile, adult). In addition, the paper discusses the use and management of insects in farmed, wild, and research contexts. The publication in its entirety can be reviewed here. The original publication was authored by Matilda Gibbons, Andrew Crump, Meghan Barrett, Sajedeh Sarlak, Jonathan Birch, and Lars Chittka.

Major Takeaway

We find strong evidence for pain in adult insects of two orders (Blattodea: cockroaches and termites; Diptera: flies and mosquitoes). We find substantial evidence for pain in adult insects of three additional orders, as well as some juveniles. For several criteria, evidence was distributed across the insect phylogeny, providing some reason to believe that certain kinds of evidence for pain will be found in other taxa. Trillions of insects are directly impacted by humans each year (farmed, managed, killed, etc.). Significant welfare concerns have been identified as the result of human activities. Insect welfare is both completely unregulated and infrequently researched.

Given the evidence reviewed in Gibbons et al. (2022), insect welfare is both important and highly neglected.

Research Summary

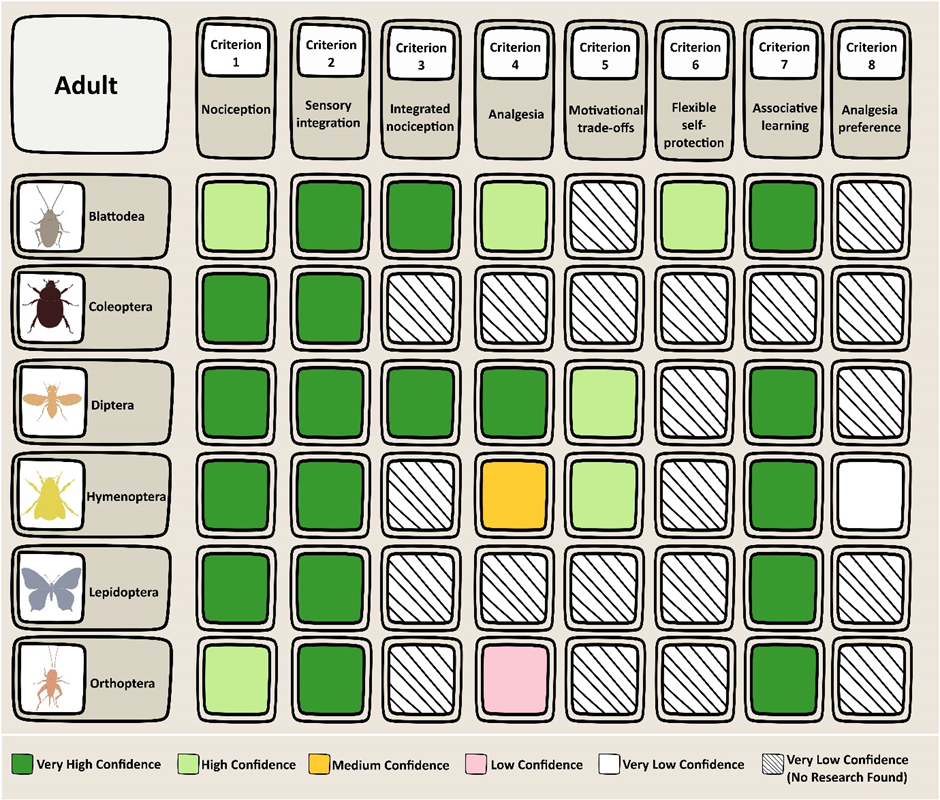

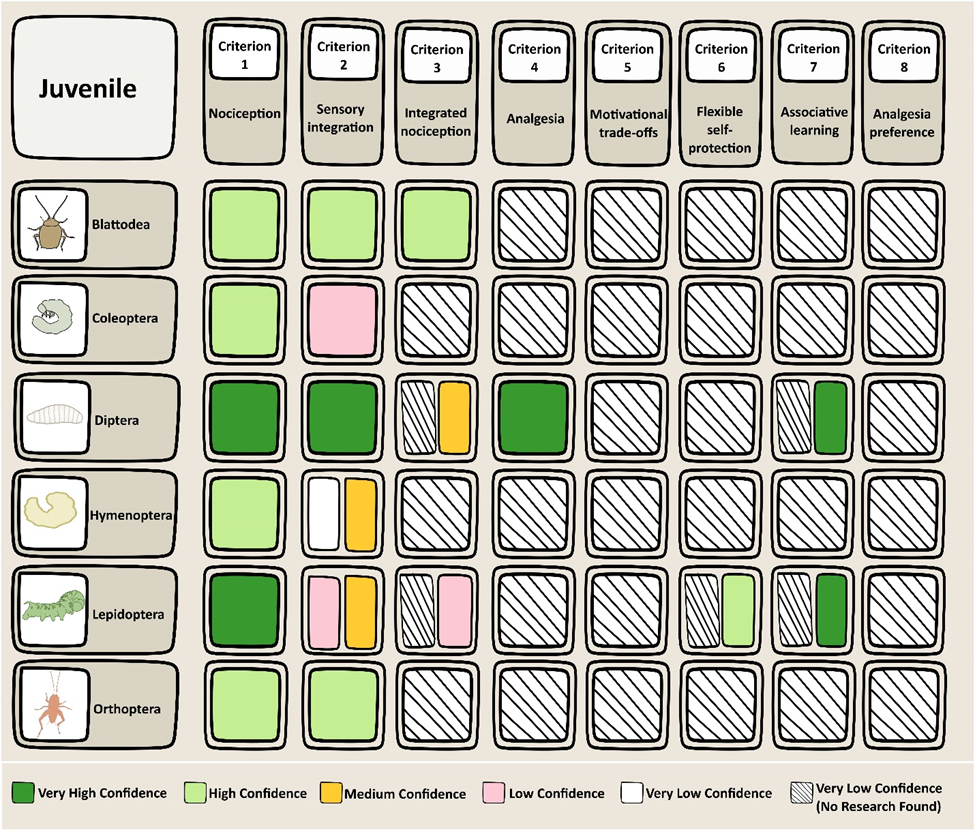

The Birch et al. (2021) framework, which the UK government has applied to assess evidence for animal pain, uses eight neural and behavioral criteria to assess the likelihood for sentience in invertebrates: 1) nociception; 2) sensory integration; 3) integrated nociception; 4) analgesia; 5) motivational trade-offs; 6) flexible self-protection; 7) associative learning; and 8) analgesia preference.

Definitions of these criteria can be found on pages 4 & 5 of the publication’s main text.

Gibbons et al. (2022) applies the framework to six orders of insects at, minimally, two developmental time points per order (juvenile, adult).

Insect orders assessed: Blattodea (cockroaches, termites), Coleoptera (beetles), Diptera (flies, mosquitoes), Hymenoptera (bees, ants, wasps, sawflies), Lepidoptera (butterflies, moths), Orthoptera (crickets, katydids, grasshoppers).

Adult Blattodea and Diptera meet 6⁄8 criteria to a high or very high level of confidence, constituting strong evidence for pain (see Table 1, below). This is stronger evidence for pain than Birch et al. (2021) found for decapod crustaceans (5/8), which are currently protected via the UK Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act 2022.

Adults of the remaining orders (except Coleoptera) and some juveniles (Blattodea, Diptera, and last juvenile stage Lepidoptera) satisfy 3 or 4 criteria, constituting substantial evidence for pain (see Tables 1 + 2).

We found no good evidence that any insect failed a criterion.

For several criteria, evidence was distributed across the insect phylogeny (Figure 1), including across the major split between the hemimetabolous (incomplete metamorphosis) and holometabolous (complete metamorphosis) insects. This provides some reason to believe that certain kinds of evidence for pain (e.g., integrated nociception in adults) will be found in other taxa.

Our review demonstrates that there are many areas of insect pain research that have been completely unexplored. Research gaps are particularly substantial for juveniles, highlighting the need for more work across developmental stages.

Additionally, our review could not capture within-order variation in neuroanatomical development or behavior, as most data within an order were from only one or two species. Further research on within-order variation, particularly for juveniles, will be necessary.

Table 1. Confidence level for each criterion for adults of each focal insect order.

Table 2. Confidence level for each criterion for juveniles of each focal insect order.

Contact Information

Questions on the study results should be directed to Dr. Lars Chittka, the corresponding author, here: l.chittka@qmul.ac.uk

Questions on how the effective altruism community can improve insects’ lives can be directed to Rethink Priorities here; and/or by emailing Dr. Meghan Barrett, here: meghan@rethinkpriorities.org

Acknowledgements

Barrett collaborates with Rethink Priorities on topics related to insect welfare. However, this project was not funded by or associated with Rethink Priorities and was conducted independently by Barrett, in collaboration with Gibbons, Crump, Sarlak, Chittka, and Birch.

This is so cool

Highlighting:

My current credence in the ability of decapod crustaceans to feel pain is really high, so seeing that there’s more evidence for Blattodea and Diptera (on these criteria) is huge, thank you!

I agree that this is huge, but it’s also depressing. A lot more needs to be done.

I agree, but I feel it’s very depressing above everything else. Saying:

feels so wrong to me. It’s like finding out there are 10 million people being tortured and saying “wow, great discovery, great research”. Of course it is great research but it just sound so wrong. Every extra square filled out in green should probably feel like reading about another 10.000 people dying in Ukraine. Of course it is very hard to feel empathy for insects on an emotional level but I guess we can try.

I also felt a bit queasy when I read it, but I don’t think that it is a bad reaction. When an area is so neglected that it’s hard to find great reviews, being enthusiastic when someone does some very good work is probably a good first step. Also, even though some emotional empathy can be a good way to stay motivated, too much of it would be crushing, especially when we talk about the suffering of billions or trillions of beings. I don’t think that feeling enough empathy should be a goal. But I understand your feelings, and they make sense. I’m also mostly sad.

Why are you so sure that if insects are conscious, their lives contain more suffering than happiness?

Thank you again for this work and posting it on EA Forums. I love the presentation of the research summary.

Is there any animal that is found to fail these criteria?

Multiple groups of animals do fail certain, or even likely all, criteria. For example, sponges do not have neurons and therefore fail criteria 1 − 3. Although I’m not aware of tests of 4-8 in the sponges, it seems reasonable to suppose that the lack of a nervous system would also preclude endogenous neurotransmitter systems and many of the behavioral criteria.

Importantly, it is not just the number of criteria but also which criteria are fulfilled when considering the likelihood of pain or sentience. Some criteria provide more important evidence for sentience than others. In particular, criteria 2⁄3 and 5 have been considered important evidence by many philosophers and scientists. The roundworm, C. elegans, fails criterion 2 according to Irvine (2022); we can have reasonably high confidence that this failure is not due to an absence of evidence, but rather evidence of absence, given that we have a complete connectome of the C. elegans nervous system (302 neurons per animal). The fact that all adult insects fulfill criterion 2 with very high confidence, and that we find fulfilment of criterion 3 across the Holo/Hemimetabola split (suggesting the potential for broad taxonomic conservation of this criterion), is a meaningful distinction between these animal groups (at least to me, in the context of this framework).

Irvine E (2022) Independence, weight, and priority of evidence for sentience. Animal Sentience 32 (10). DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1724.

This comment is representative only of MRB’s opinions and expertise, and not the other post/publication authors.

(Not an animal scientist or a scientist of any nature btw!)

I’d guess sessile animals (e.g. mussels) fail (at least) motivational tradeoffs and analgesia preference.

I wanted to note that I really appreciate the robust discussion about, and interest in, this post. As an insect neuroecologist and physiologist, it’s gratifying to see a community of folks engaging with insect neuroscience and behavior in such a meaningful way.

I really do encourage folks to read the full paper—it addresses many of the things you might be interested in (it’s hard to capture 75 pages of research in only 1000 words, so we necessarily lost some detail). If for some reason you can’t access it, I’m happy to share a pdf copy or you can email Dr. Chittka, the corresponding author for the paper.

I’ve reached my time limit for replying to comments here, so please don’t take any future silence as indicative that your questions are in any way bad/uninteresting/I don’t care about them. I’ve just gone back to being busy doing more research on bugs.

I saw the line “found no good evidence that anything failed any criterion”, but just to check explicitly: What do the confidence levels mean? In particular, should I read “low confidence” as “weak evidence that X feels pain-as-operationalized-by-Criterion Y”? Or as “strong evidence that X does not feel pain-as-operationalized-by-Criterion Y”?

In other words:

Suppose you did the same evaluation for the order Rock-optera (uhm, I mean literal rocks). (And suppose there was literature on that :-).) How would the corresponding row look like? All white, or would you need to add a new colour for that?

Suppose you found 1000 high-quality papers on order X and Criterion Y, and all of them suggested that X is precisely borderline between satisfying Y vs not satisfying it. How would this show up in the tables?

Nitpicky feedback on the presentation:

If I am understanding it correctly, the current format of the tables makes them fundamentally incapable of expressing evidence for insects being unable to feel pain. (The colour coding goes from green=evidence for to red=no evidence, and how would you express ??=evidence against?) I would be more comfortable with a format without this issue, in particularly since it seems justified to expect the authors to be biased towards wanting to find evidence for. [Just to be clear, I am not pushing against the results, or against for caring about insects. Just against the particular presentation :-).]

After thinking about it more, I would interpret (parts of) the post as follows:

To the extent that we found research on these orders O and criteria C, each of the orders satisfies each of the criteria.

We are not saying anything about the degree to which a particular O satisfies a particular C. [Uhm, I am not sure why. Are the criteria extremely binary, even if you measure them statistically? Or were you looking at the degrees, and every O satisfied every C to a high enough degree that you just decided not to talk about it in the post?]

To recap: you don’t talk about the degrees-of-satisfying-criteria, and any research that existed pointed towards sufficient-degree-of-C, for any O and C. Given this, the tables in this post essentially just depict “How much quality-adjusted research we found on this.”

In particular, the tables do not depict anything like “Do we think these insects can feel pain, according to this measure?”. Actually, you believe that probably once there is enough high-quality research, the research will conclude that all insects will satisfy all of the criteria. (Or all orders of insects sufficiently similar to the ones you studied.)

[Here, I mean “believe” in the Bayesian sense where if you had to bet, this is what you would bet on. Not in the sense of you being confident that all the research will come up this way. In particular, no offense meant by this :-) .]

Is this interpretation correct? If so, then I register the complaint that the post is a bit confusing—not particularly sure why, just noticing that it made me confused. Perhaps it’s the thing where I first understood the tables/conclusions as “how much pain do these types of insects feel?”. (And I expect others might get similarly confused.)

These are great questions. I want to say at the outset here: we explicitly chose to stick closely and without major adjustments to the Birch et al. 2021 framework for this review, such that our results would be directly comparable to their study of decapods and cephalopods that led to the protection of those groups in the Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act 2022 in the UK.

Here is what the paper says about the framework, and the confidence levels:

So, to be clear the colors are not ratings of ‘very high confidence that they satisfy the criteria’ but rather ‘very high confidence that we can determine whether they satisfy or fail the criteria’. This is why it’s important that we clarify that there is no evidence that insects fail any criteria. Green happens to mean ‘satisfies’ and not ‘fails’ in all cases for our study, but that’s a result of how the evidence shakes out—and not specified by the framework itself, which does allow for the collection of ‘evidence against’ the criterion.

So, in Rockoptera—let’s imagine we had really, really high quality evidence that they did not meet any criteria. We would find a row of green boxes—we are very highly confident in our determination that they fail 8⁄8 criteria. Then, when we do our final summation of the evidence, as in Section 4 of the paper: satisfying 0⁄8 criteria is classified as “capacity for pain unknown or unlikely” in the group. They explicitly state “If remaining indicators are uncertain [e.g., white/red] rather than shown absent, sentience (or pain) is simply unknown. However, if high-quality scientific work shows the other indicators to be absent [e.g., green], pain is unlikely” (emphasis and brackets mine). So, we would say, according to Birch et al. 2021 that we have very high confidence that pain is unlikely in Rockoptera. Whew! :)

I do think there’s the potential here for color = “pain satisfaction” to be a common misunderstanding; so it seems like future iterations of this work (as you note) might be presented more clearly by adding some kind of symbology that interacts with the color, such that you know whether green = satisfy vs. fail upon immediately looking at it.

Last thought—re: 1000 high quality papers, split down the middle and with no way to resolve the data by considering the biological context. I would classify this as ‘Medium confidence’ - we do not have the evidence to be convinced of satisfaction or failure (e.g., high) but the evidence is apparently neither little nor flawed (e.g., low).

This comment is representative only of MRB’s opinions and expertise, and not the other post/publication authors.

I replied to your comment before you edited it and added the following, so I will make quick replies to these new questions throughout.

To the extent that we found research on these orders O and criteria C, each of the orders satisfies each of the criteria.

- I would rephrase: For the OxC combinations that we found enough research to make a determination about whether each order O satisfies or fails each criterion C, we found that each order satisfied each criterion.

We are not saying anything about the degree to which a particular O satisfies a particular C. [Uhm, I am not sure why. Are the criteria extremely binary, even if you measure them statistically? Or were you looking at the degrees, and every O satisfied every C to a high enough degree that you just decided not to talk about it in the post?]

- These criteria, like many in science, are actually particularly binary. E.g., you either have nociceptors or you do not have nociceptors (you either are an insect, or you are not an insect!). So, in this way, we are assessing satisfaction/failure in a binary sense.

- But, of course, there are relevant degrees that emerge after determining satisfaction or failure. For example, you might have more types or fewer types of nociceptors. They might be expressed in greater or fewer numbers. Ion channels could be expressed in different types of cells or sequestered on the interior of the cell following expression for different amounts of time/due to different physiological causes. In all cases, these degrees would not change our determination about whether the animal group possesses nociceptors (e.g., satisfies/fails the criterion). But, of course, these degrees might have some relevant effects on our eventual credence for pain! We do spend some time on this in the paper (which is 75 pages and I could not replicate here! But see criterion 7 for some of this light discussion of degrees).

- To my mind, the point of this framework, and determining pass/fail for the criterion, is to 1) determine whether it is worth taking the idea of pain seriously in an animal group (e.g., providing evidence for or against applying some version of a precautionary principle); and 2) determining where we should direct research effort by identifying areas where we don’t yet have high-quality evidence for or against the satisfaction of criteria that might be relevant to insect pain.

To recap: you don’t talk about the degrees-of-satisfying-criteria, and any research that existed pointed towards sufficient-degree-of-C, for any O and C. Given this, the tables in this post essentially just depict “How much quality-adjusted research we found on this.”

- We talk about this briefly, for criterion 7, but to be clear, there was relatively little ‘degrees-of-satisfying’ evidence to be found in insects at this time. In most OxC cases, as the table demonstrates, there wasn’t even sufficient evidence to demonstrate with high/very high confidence that the order met or failed to meet the binary condition of the criterion – much less the degrees of meeting/failure, after having met or failed it.

In particular, the tables do not depict anything like “Do we think these insects can feel pain, according to this measure?”. Actually, you believe that probably once there is enough high-quality research, the research will conclude that all insects will satisfy all of the criteria. (Or all orders of insects sufficiently similar to the ones you studied.)

[Here, I mean “believe” in the Bayesian sense where if you had to bet, this is what you would bet on. Not in the sense of you being confident that all the research will come up this way. In particular, no offense meant by this :-) .]

- I don’t really understand the first part of this. But I guess I would say that the table itself doesn’t represent any particular quantifiable credence that insects feel pain. However, the summation of these lines of evidence can provide some traction for thinking about how seriously to take the idea of insect pain at all—even if it again doesn’t give us any particular credence level.

- Re: point 2, I strongly disagree that this is my belief. I believe that once there is enough high quality research for each criterion and order, we will be able to conclude whether or not insect orders satisfy or fail all criteria. There are a select few criteria where available evidence suggests that we might bet on more research coming up satisfactorily – e.g., criterion 3 in adults, where evidence for integrated nociception is distributed across the phylogeny and criterions 1 + 2 (the preconditions) are also robustly met, plus we know that both 1 + 2 are robustly conserved across all the insect orders. However, in most O x C cases we have very, very little data – or even no real data (criterion 8, particularly!) – that can lead us to make any specific or generalizable conclusions about the likelihood of any or all insects meeting that criterion.

This comment is representative only of MRB’s opinions and expertise, and not the other post/publication authors.

Once again, researchers fail to distinguish between “pain” and “suffering.”

https://www.mattball.org/2022/10/ed-yong-on-insects.html

Open Phil is pretty much the only place I’ve seen that’s done a good job of honestly exploring this distinction:

https://www.openphilanthropy.org/research/2017-report-on-consciousness-and-moral-patienthood/

What indicators of consciousness do you expect mammals and birds to have that insects don’t? (Edited to avoid suggesting I’m only asking about the criteria in this post.)

I think criteria 5-8 suggest it’s not mere nociception. Of course, they might not establish consciousness, but what more do you expect to do so?

Personally, I’m very sympathetic to Luke Muehlhauser’s views in that report and, in particular, illusionism and AST (he doesn’t explicitly endorse AST, but I think he said it was the closest attempt), and I still don’t think they rule out insect consciousness or imply we should assign it very low probability. He gave fruit flies 10% and 25% probabilities of consciousness in that report, with 25% closer to his actual views at the time. This seems too high to completely ignore.

I fail to see any lack of distinguishing as I do not see any claim on suffering or capacity to suffer in insects, only on insects’ abilities to feel pain.

How physical pain relates to subjectively perceived suffering is a whole other topic, and as far as I can tell no subject to this review. (Though I’ve only read this post, not the review itself.)

I do see that pain-feeling is usually perceived as something innately suffering-inducing, and I see why that’s the case. If pain is not somewhat negative for the organism experiencing it, why would that mechanism establish itself across whole species in the first place? Could be that pain in insects acts merely as a reflex trigger and no experience/suffering in the moral sense is involved at all, but I really argue that this is a whole other claim and topic.

The Open Phil report you linked shows quite well how little we know and how complex this issue is, and that jugdements rely heavily on claims and intuitions due to lack of understanding.

So as we do not really know how the ganglions of insects (let alone our brains) work and what consciousness or conscious experience really is about, I’ be very careful with making definite claims about the suffering capacities of other species.

As far as I can tell, the authors of this review made a good job of evaluating the physical ability of insects to feel pain. This is but the first step to assign moral patienthood to insects; it’s a necessary, but not sufficient criteria.

The likelihood of an organism to be able to suffer is significantly higher if that organism is known to feel pain. I personally tend to err on the worse case and assume pain-feeling organisms are suffering, rather than risk neglecting substantial suffering as the odds seem high enough. (But that’s just my personal take.)

I see how the concepts get mingled up inappropriately, but I would not go as far as to demand a clarification on that from any scientific publication dealing with pain (in organisms other than human), especially since there is no sufficiently backed-up concept of consciousness or moral patienthood. In my opinion arguing about wether pain-feeling and suffering can be used anagolous should happen, but it’s probably not the responsibility of the authors here.

Thank you Meghan Barrett for this summary. I really like the table view, and I hope this topic will be more popular for society.

Thanks for sharing! I particularly liked tables 1 and 2.

Do you have any thoughts on the effect on moral weight of the satisfaction of each pain criterion, besides the fact it increases as more criteria are satisfied? It seems like this research could be very valuable to adjust the heuristic according to which moral weight is directly proportional to the number of neurons.

Vasco—thanks so much! Sajedeh did a wonderful job with the tables (as well as many other great figures in the publication itself).

Rethink Priorities has an interdisciplinary team working on the many complexities of moral weight (including how important to consider neuron numbers). I know more work will be coming out from that team in the next two weeks on this topic, which I’m sure they can speak about more elegantly and critically than I can.

You can follow that project here: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/s/y5n47MfgrKvTLE3pw

This comment is representative only of MRB’s opinions and expertise, and not the other post/publication authors.

I now get an error for the link at the top of the post; here’s another link I found which currently works: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0065280622000170

Hi Meghan,

Do you have any guesses about whether the lives of wild terrestrial arthropods are positive or negative? Knowing this would be important to assess changes in their population size. If they are negative as predicted by the Weighted Animal Welfare Index of Charity Entrepeneurship, decreasing (increasing) the population would be better (worse) everything else equal. Of course, everything else is never equal, and this questions is quite complex (e.g. due to trophic cascades).

I understand the question is not explicitly covered by your study, but any thoughts would be welcome. Feel free to pass the question too (I read your note here).

What, if anything, does this imply about the hundreds of millions of insecticide-treated bednets we have helped distribute?