Focusing on bad criticism is dangerous to your epistemics

TL;DR: Really low quality criticism[1] can grab my attention — it can be stressful, tempting to dunk on, outrageous, etc. But I think it’s dangerous for my epistemics; spending a lot of time on bad criticism can make it harder to productively reflect on useful criticism.

This post briefly outlines why/how engaging with bad criticism can corrode epistemics and lists some (tentative) suggestions, as I expect I’m not alone. In particular, I suggest that we:

Avoid casually sharing low-quality criticism (including to dunk on it, express outrage/incredulity, etc.).

Limit our engagement with low-quality criticism.

Remind ourselves and others that it’s ok to not respond to every criticism.

Actively seek out, share, and celebrate good criticism.

| I wrote this a bit over a year ago. The post is somewhat outdated (and I’m less worried about the issues described than I was when I originally wrote it), but I’m publishing it (with light edits) for Draft Amnesty Week. 🦋 |

Notes on the post:

It’s aimed at people who want to engage with criticism for the sake of improving their own work, not those who might need to respond to various kinds of criticism.

E.g. if you’re trying to push forward a project or intervention and you’re getting “bad criticism” in response, you might indeed need to engage with that a lot. (Although I think we often get sucked into responding/reacting to criticism even when it doesn’t matter — but that might be a discussion for a different time.)

It’s based mostly on my experience (especially last year), although some folks seemed to agree with what I suggested was happening when I shared the draft a year ago.

Some people seem to think that it’s bad to dismiss any criticism. (I’m not sure I understand this viewpoint properly.[2]) I basically treat “some criticisms aren’t useful” as a given/premise here.

As before, I use the word “criticism” here for a pretty vague/broad class of things that includes things like “negative feedback” and “people sharing that they think [I or something I care about is] wrong in some important way.” And I’m talking about criticism of your work, of EA, of fields/projects you care about, etc.

See also what I mean by “bad criticism.”

How focusing on bad criticism can corrode our epistemics (rough notes)

Specific ~belief/attitude/behavior changes

I’m worried that when I spend too much time on bad criticisms, the following things happen (each time nudging me very slightly in a worse direction):

My position on the issue starts to feel like the “virtuous” one, since the critics who’ve argued against the position were antagonistic or clearly wrong.

But reversed stupidity is not intelligence, and low-quality or bad-faith arguments can be used to back up true claims.

Relatedly, I become immunized to future similar criticism.

I.e. the next time I see an argument that sounds similar, I’m more likely to dismiss it outright.

See idea inoculation: “Basically, it’s an effect in which a person who is exposed to a weak, badly-argued, or uncanny-valley version of an idea is afterwards inoculated against stronger, better versions of that idea. The analogy to vaccines is extremely apt — your brain is attempting to conserve energy and distill patterns of inference, and once it gets the shape of an idea and attaches the flag “bullshit” to it, it’s ever after going to lean toward attaching that same flag to any idea with a similar shape.”

I lump a lot of different criticisms together into an amalgamated position “the other side” “holds”

I start to look down on criticisms/critics in general; my brain starts to expect new criticism to be useless (and/or draining).

Which makes it less likely that I will (seriously) engage with criticism of any kind in the future.

Feedback (or criticism) fatigue

Additionally, I think engaging with a lot of criticism is emotionally difficult for most people, and makes it broadly harder to engage with every new criticism in a productive way. So (especially if we’re already getting a lot of criticism) we should be somewhat selective in what we engage seriously with.

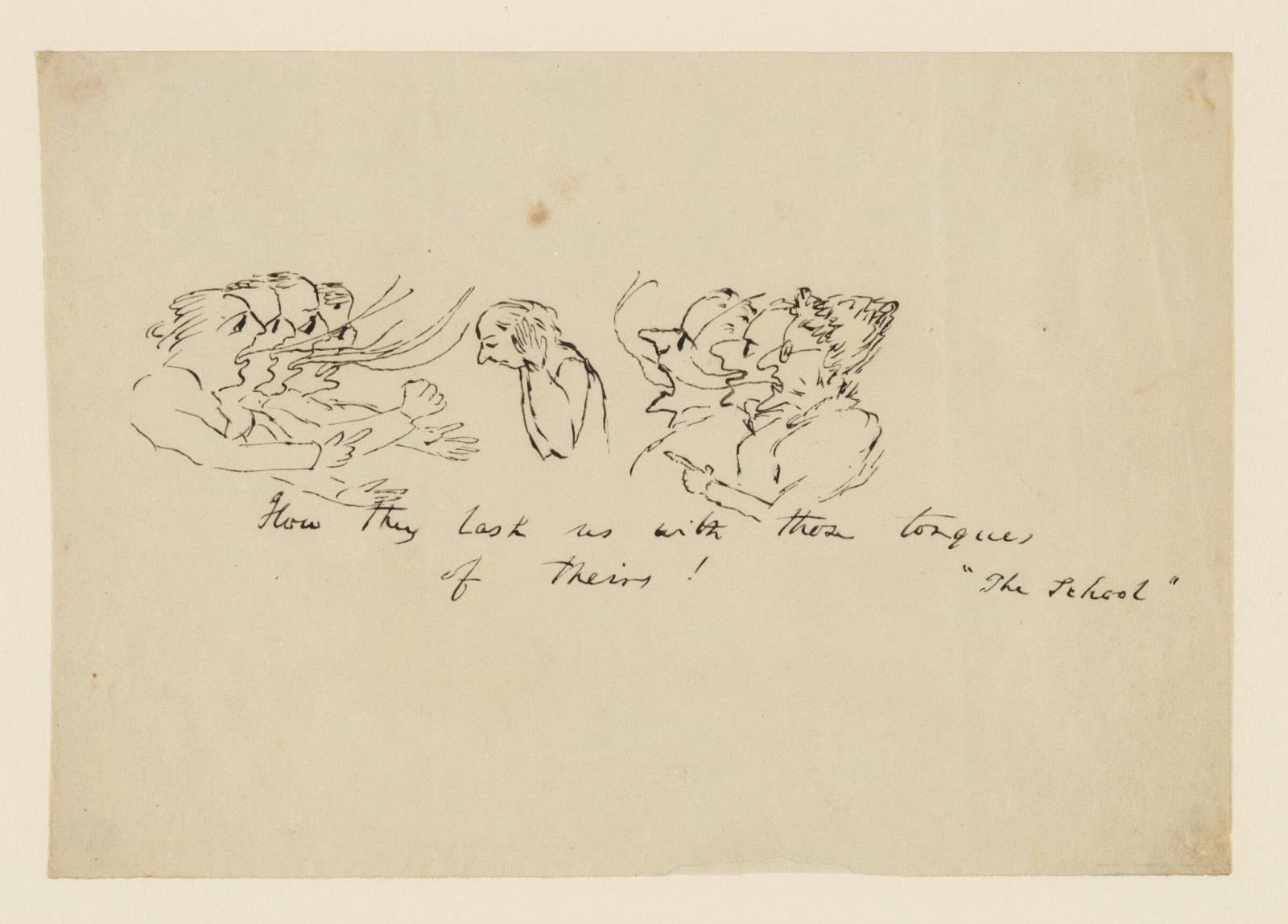

In the framework of this highly accurate & researched diagram, we should make sure we’re getting the “best” feedback before we’re too tired to engage with new feedback productively.

Danger factors

We’re particularly susceptible (i.e. we’re bad at productively engaging with criticism) when:

We’re stressed or tired (emotionally or otherwise)

We’ve recently gotten a lot of criticism

We or something we care about (the thing being criticized) is in a precarious situation

(Probably not an exhaustive list.)

Some suggestions

I think we should probably try to engage more with high-quality criticism, and less with low-quality criticism. In particular:

Avoid casually sharing low-quality criticism, at least without explaining why it might be relevant or useful (including to dunk on it, express outrage/incredulity, etc.).

People or groups who are being criticized a lot sometimes joke around about recent low-quality criticism (I do this, too), but I think this often encourages a dismissive/condescending or tribal mindset towards a pretty broad set of criticisms.

Limit your own engagement with low-quality criticism.

Maybe view low-quality criticism as basically spam; block people on social media if they share it a lot, remind yourself that this is probably a waste of time/energy, resist the urge to read the dramatic criticism (resist the FOMO?), etc. Consider giving yourself a regular quota of time to spend on this kind of criticism, if you tend to get sucked in (and maybe timebox engagement with specific criticisms).

Remind people (and yourself) that it’s ok to not respond to every criticism.

(And support them if they feel pressured to respond.)

Actively seek out, share, and celebrate good criticism.

Relatedly, help improve the average quality of criticism that people hear, e.g. by helping (good-faith) critics with their work. One way to do this is to be more legible; criticism will be better if people know more about the thing they’re criticizing, so they’re criticizing the right thing.

Also relatedly, consider “translating” good or potentially-important points from bad criticisms into a form that’s easier for people to engage with. E.g. if there’s a new polemic that makes a bunch of poor arguments or random accusations that also includes some interesting points, consider summarizing and sharing those.

Other suggestions (not related to limiting engagement):

Notice these phenomena and try to train yourself to notice if e.g. you’re allowing yourself to lump all criticisms on a certain topic into one pile (in a way you don’t endorse).

Share more positive feedback.

We could try to address each of the issues I listed separately, e.g. by learning to correct somewhat misguided criticisms until they’re more useful, trying to steelman criticisms[3], etc.. I general, do think it’s quite valuable to broadly teach ourselves to engage productively with all sorts of criticism.

Note that there’s a real danger that we’ll be biased in our assessment of what’s good or bad, and this will lead us to overlook or underweight particularly scary criticisms. I think this can be mitigated by paying attention to the failure mode, practicing skills described in “Staring into the abyss,” and e.g. asking friends whose views are far from ours to help us understand certain points of view or to sanity check our assessments sometimes.

See also

Some of my other posts on related topics

Other potentially useful/related links

Appendix: What I mean by “bad criticism”

Notes: (1) it’s not about the tone,[4] (2) I’m not carefully differentiating between how I’m using “bad” vs. “unhelpful” vs. “low-quality,” (3) I’m not listing specific examples, and (4) criticism can be more or less “bad.”

When I say “bad criticism,” I’m generally thinking of criticism that:

Is deliberately misleading (strawmans) or seriously mischaracterizes what is being criticized

Made-up example: “The EA Forum is terrible because it’s a pro-big-oil lobbying coordination platform…”

Is just very wrong about the points being made

I.e. the premises might be right, but the arguments don’t make sense/ the conclusions don’t follow. Maybe the criticism just doesn’t really make sense.

Lacks substance; it just insinuates that something is bad

Some things tend to make criticisms worse, but critiques with these qualities might still be pointing to something important. Examples:

It’s extremely unspecific (or doesn’t really argue its point, heavily over-generalizes from one example, etc.)

The person writing has an agenda

The writer doesn’t seem to (try to) understand your perspective, and maybe the criticism ignores tradeoffs or frames complicated issues as black-and-white[5]

It seems to be (part of) a bravery debate (see also this shortform)

Parts of the criticism are wrong

It’s very overconfident

It lists a large number of possible arguments for its claim, and it’s not clear which are actually important to the author (see relevant discussion), or maybe the arguments are just very hard to clarify enough to argue with them

It’s exaggerated, hostile, mocking, or sarcastic

It employs (possibly accidentally) various ~rhetorical tricks, like:

“Cat couplings” (“naive optimism” in the quote: “Pessimism has its downsides, but is still preferable to naive optimism”), using very loaded words, using loaded analogies

Implying that X is bad because of Y, then arguing emphatically/thoroughly for why Y is true — a point most readers almost certainly agree with — and never seriously explaining the logical connection between “X is bad” and “Y is true.”

Spuriously citing stuff

Implying that readers are bad if they disagree (“obviously any reasonable person believes…”)

- ^

Of your work, of EA, of fields/projects you care about, etc. See the Appendix in the post for what I mean by “low quality” or “bad” criticism.

- ^

Maybe it’s something like; we’re bad at identifying which criticisms are low-quality because we’re biased, so we should err very heavily on the side of engaging with all criticism as if it might be informative/useful. I think there’s some truth to the premise, but I do think it’s reasonably possible to accurately determine that some criticism (of your work) isn’t actually helpful and the costs probably outweigh the benefits for me.

- ^

People have pointed out various potential issues with steelmanning — I’m not getting into this now.

- ^

Changing the tone of criticism can make it easier to respond to productively, though, and e.g. if I’m trying to create a healthy/good team culture, I would aim for productive tones, too (not just substance).

- ^

Although beware: The fallacy of gray is a common belief in people who are somewhat advanced along the path to optimal truth seeking which claims, roughly, that because nothing is certain, everything is equally uncertain.

More see also:

This comment I wrote a while ago

Other people are wrong vs I am right

The cow pox of doubt

Yeah more broadly I try to only share criticism if it has points that someone thinks are valuable. I don’t think it’s defensible to say “oh I thought people might want to read it”. I should take responsibility—“why am I putting it in front of people”.

Nice! I realised that I can’t think of the last time I received low-quality criticism (but can think of a moderate amount of fairly high-quality criticism) so I am probably quite lucky in that regard, as my work/writing thus far has either been privately shared or public but not very provocative. (Of course the flipside is having more people engage with one’s writing is one way to increase impact.)

I hadn’t heard the “idea inoculation” term before—that does seem like a useful framing. I wonder if that is part of the explanation for some of the AI safety/x-risk backlash, that someone hears a third-hand snippet of an argument for why AGI/TAI might be dangerous, or consumes some not-very-realistic fiction about this, and later is pretty reluctant to engage with more careful work on the subject.

I think in general the argument makes sense, but I’d point a few things:

Bad arguments of the fallacy type actually do not take a long time to reply to. You can simply suggest to the person that you think X is a fallacy because of Y and move on.

Bad arguments of the trolling type require you detecting when a person is not interested in the argument itself but making you angry, etc. Trolling is typically a feature of anonymous communication, although some people enjoy doing this face-to-face. In general, one should avoid feeding the trolls, of course, because doing so achieves nothing other than to entertain (or even give money to in certain platforms) the troll. In person, throw the troll-might-be your best argument and see how they react. If their answer does not reveal reflection, just move on.

“Bad arguments” of the sort “people just say X is wrong” typically just reveal a difference in values. It’s possible to argue, e.g., about the positive and negative things associated with a given thing (e.g., homosexuality, cultural appropriation), but it’s not possible to argue the valence of the thing in itself (e.g., whether these things are bad in and of themselves). Sometimes you can argue based on internal logic of a value system (e.g., “Ok, so you think homosexuality is bad because the Bible says so, but it also says you shouldn’t eat pork or seafood and you do it. Why do you care about it for some things and not others?”), but I find these discussions are usually not worth it unless done for enjoyment of both parties or between people who will have a long-term close relationship, in which value-alignment or at least value-awareness is important.

In general, I think it’s good to practice letting go and just accepting that you can’t win every argument or change everyone’s mind on any one thing. I’d say Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Meditation might be good suggestions for people who frequently get worked up after an argument with others and that ruminate (with associated negative feelings) on the argument for hours to days after the fact.

good post! enjoyed reading this.