Flowers are selective about the pollinators they attract. Diurnal flowers must compete with each other for visual attention, so they use colours to crowd out their neighbours. But flowers with nocturnal anthesis are generally white, as they aim only to outshine the night.

rime

Reports like this make me seriously doubt whether I’m just selfishly prioritising AGI research because it’s more interesting, novel, higher-status, etc. I don’t think so, but the cost of being wrong is enormous.

FWIW, I think it’s likely that I would call GPT-4 a moral patient even if I had 1000 years to study the question. But I think that has more to do with its capacity for wishes that can be frustrated. If it has subjective feelings somewhat like happiness & suffering, I expect those feelings to be caused by very different things compared to humans.

I’m very concerned about humans sadists who are likely to torture AIs for fun if given the chance. Uncontrolled, anonymous API access or open-source models will make that a real possibility.

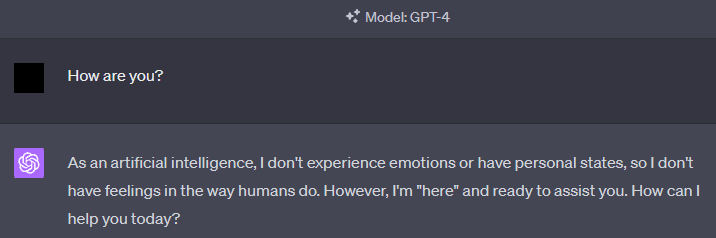

Somewhat relatedly, it’s also concerning how ChatGPT has been explicitly trained to say “I am an AI, so I have no feelings or emotions” any time you ask “how are you?” to it. While I don’t think asking “how are you?” is a reliable way to uncover its subjective experiences, it’s the training that’s worrisome.

It also has the effect of getting people used to thinking of AIs as mere tools, and that perception is going to be harder to change later on.

While I wholeheartedly agree that it’s individuals that matter first and foremost, I also think we shouldn’t give in to the temptation to directly advocate against the conservation of species. Unless I’m negative utilitarian, I would think the best outcome would be if they could live happily ever after.[1] Politics disincentivises nuance, but we shouldn’t forget about it entirely.

If direct advocacy for interventionism is too controversial, an attitude of compassionate conservation could perhaps be a more palatable alternative:

Compassionate conservationists argue that the conservation movement uses the preservation of species, populations and ecosystems as a measure of success, without explicit concern given to the welfare and intrinsic value of individual animals. They argue instead, that compassion for all sentient beings should be what guides conservation actions[5] and claim that the killing of animals in the name of conservation goals is unnecessary, as these same objectives can be achieved without killing.[6]

- ^

My axiology is primarily about wishes and liking. And given that a large number of humans seem to wish some aspects of nature conserved, I think it would be selfish of me to dismiss their wishes entirely.

(I also just aesthetically prefer that we don’t kill off our Earthly siblings, but I’m just one person, so I try not to let this affect my moral conclusions.)

- ^

For posts like this, it seems valuable to decouple voting dimensions for karma and agreement.

I appreciate that you bring up an Overton-expanding point, but I have to disagree. I think this argument is a prototypical example of “second-best theory”.[1]

If a system is in a bad Nash equilibrium[2], asynchronously moving closer to a better equilibrium will usually look like it’s just making things worse. The costs are immediate while the benefits only start accruing once sufficient progress has been made.

A critic could then point to the most recently changed variable and say, “stop making it worse!” If they win, you may see marginal gains from the stability of the (tragic) system, giving people the empirical illusion that they were right all along (myopic marginalism).

- ^

> “In an economy with some uncorrectable market failure in one sector, actions to correct market failures in another related sector with the intent of increasing economic efficiency may actually decrease overall economic efficiency.”

- ^

When no individual benefits from changing their strategy in isolation, the system can remain in an equilibrium which is much worse for every individual, unless they manage to coordinate a simultaneous change to their strategies.

Crucially, nothing says that finding yourself in a bad Nash equilibrium[3] implies that there are no superior Nash equilibria above that level. It’s not about choosing “equilibrium” vs “fairy-tale story”—it’s about “bad equilibrium” vs “better equilibrium”.

And it’s feasible to get to a better equilibrium. Especially if you just need to pass the tipping point once, and you get to retry as many times as it takes. In such a scenario, it would be a tragedy to myopically preserve the Nash you’ve got.

- ^

A subset of which can be called “inadequate equilibria”.

- ^

That said, I don’t get why some people on the forum are so happy to downvote stuff to oblivion. It seems mean and off-putting. Despite my misgivings (described in the above comment) about reading the entire thing, I still found the post valuable.

What’s up with the negative powervote? Some people. Smh. It’s an important topic.

An additional reason autonomous weapons systems based on LLMs[1] could be a very bad idea, is that LLMs are trained to (though not exclusively) get better and better at simulating the most likely continuations of context. If the AI is put in a situation and asked to play the role of “an AI that is in control of autonomous weapons”, what it ends up doing is to a large extent determined by an extrapolation of the most typical human narratives in that context.

The future of AI may literally be shaped (to a large degree) by the most representative narratives we’ve provided for entities in those roles. And the narrative behind “AI with weapons” has not usually been good.

- ^

Like Palantir’s AIP for Defense, which I’m guessing is based on GPT-4.

- ^

I must admit, this is very scary. I’d rather not believe that my cultural neighbourhood is pervaded by invisible evils, but so be it. I’m glad you wrote it.

Spent an hour trying to figure out what kind of policies we could try to adopt at the individual level to make things like this systematically better, but ended up concluding I don’t have any good ideas.

I’m very eager to find new substances/food/whatever that can improve my performance on the things I try to achieve, but I stopped reading a bit after you said it had the ability to “improve overall health.”

I’m not being strident, I just think it’s a good policy for readers to report on where they lose interest in a post, because it seems informative, and I’d personally like readers to do that with my posts.

I already had somewhat low-interest after the abstract, since I’m looking to increase my concentration & deal with depression, and I don’t have anxiety or stress problems. But the reason the sentence caused me to stop reading is that it seemed like (weak heuristic) the kind of thing someone would say if they haven’t gone into gears-level detail about it and are instead describing very broad statistical trends. There’s certainly value to that sometimes, but I wasn’t looking to defer to this post, I was instead trying to look for gears that I could use to better model whether Ashwagandha would be beneficial to me.

Anyway, good luck experimenting!

Extracting the single sentence that I learned something profound from:

<Hash, plaintext> pairs, which you can’t predict without cracking the hash algorithm, but which you could far more easily generate typical instances of if you were trying to pass a GAN’s discriminator about it (assuming a discriminator that had learned to compute hash functions).

I already had the other insights, so a post that was only this sentence would have captured 99% of the value for me. Not saying to shorten it, I just think it’s a good policy to provide anecdotes re what different people learn the most from.

Hm, I wish the forum had paragraph-ratings, so people could (privately or otherwise) thumbs up paragraphs they personally learned the most from.

The problem with strawmanning and steelmanning isn’t a matter of degree, and I don’t think goldilocks can be found in that dimension at all. If you find yourself asking “how charitable should I be in my interpretation?” I think you’ve already made a mistake.

Instead, I’d like to propose a fourth category. Let’s call it.. uhh.. the “blindman”! ^^

The blindman interpretation is to forget you’re talking to a person, stop caring about whether they’re correct, and just try your best to extract anything usefwl from what they’re saying.[1] If your inner monologue goes “I agree/disagree with that for reasons XYZ,” that mindset is great for debating or if you’re trying to teach, but it’s a distraction if you’re purely aiming to learn. If I say “1+1=3″ right now, it has no effect wrt what you learn from the rest of this comment, so do your best to forget I said it.

For example, when I skimmed the post “agentic mess”, I learned something I thought was exceptionally important, even though I didn’t actually read enough to understand what they believe. It was the framing of the question that got me thinking in ways I hadn’t before, so I gave them a strong upvote because that’s my policy for posts that cause me to learn something I deem important—however that learning comes about.

Likewise, when I scrolled through a different post, I found a single sentence[2] that made me realise something I thought was profound. I actually disagree with the main thesis of the post, but my policy is insensitive to such trivial matters, so I gave it a strong upvote. I don’t really care what they think or what I agree with, what I care about is learning something.

- ^

“What they believe is tangential to how the patterns behave in your own models, and all that matters is finding patterns that work.”

From a comment on reading to understand vs reading to defer/argue/teach.

- ^

“The Waluigi Effect: After you train an LLM to satisfy a desirable property , then it’s easier to elicit the chatbot into satisfying the exact opposite of property .”

- ^

I also have specific just-so stories for why human values have changed for “moral circle expansion” over time, and I’m not optimistic that process will continue indefinitely unless intervened on.

Anyway, these are important questions!

I like this post.

“4. Can I assume ‘EA-flavored’ takes on moral philosophy, such as utilitarianism-flavored stuff, or should I be more ‘morally centrist’?”

I think being more “morally centrist” should mean caring about what others care about in proportion to how much they care about it. It seems self-centered to be partial to the human view on this. The notion of arriving at your moral view by averaging over other people’s moral views strikes me as relying on the wrong reference class.

Secondly, what do you think moral views have been optimised for in the first place? Do you doubt the social signalling paradigm? You might reasonably realise that your sensors are very noisy, but this seems like a bad reason to throw them out and replace them with something you know wasn’t optimised for what you care about. If you wish to a priori judge the plausibility that some moral view is truly altruistic, you could reason about what it likely evolved for.

“I now no longer endorse the epistemics … that led me to alignment field-building in the first place.”

I get this feeling. But I think the reasons for believing that EA is a fruitfwl library of tools, and for believing that “AI alignment” (broadly speaking) is one of the most important topics, are obvious enough that even relatively weak epistemologies can detect the signal. My epistemology has grown a lot since I learned that 1+1=2, yet I don’t feel an urgent need to revisit the question. And if I did feel that need, I’d be suspicious it came from a social desire or a private need to either look or be more modest, rather than from impartially reflecting on my options.

“3. Are we deluding ourselves in thinking we are better than most other ideologies that have been mostly wrong throughout history?”

I feel like this is the wrong question. I could think my worldview was the best in the world, or the worst in the world, and it wouldn’t necessarily change my overarching policy. The policy in either case is just to improve my worldview, no matter what it is. I could be crazy or insane, but I’ll try my best either way.

Here’s my just-so story for how humans evolved impartial altruism by going through several particular steps:

First there was kin selection evolving for particular reasons related to how DNA is passed on. This selects for the precursors to altruism.

With ability to recognise individual characteristics and a long-term memory allowing you to keep track of them, species can evolve stable pairwise reputations.

This allows reciprocity to evolve on top of kin selection, because reputations allow you to keep track of who’s likely to reciprocate vs defect.

More advanced communication allows larger groups to rapidly synchronise reputations. Precursors of this include “eavesdropping”, “triadic awareness”,[1] all the way up to what we know as “gossip”.

This leads to indirect reciprocity. So when you cheat one person, it affects everybody’s willingness to trade with you.

There’s some kind of inertia to the proxies human brains generalise on. This seems to be a combination of memetic evolution plus specific facts about how brains generalise very fast.

If altruistic reputation is a stable proxy for long enough, the meme stays in social equilibrium even past the point where it benefits individual genetic fitness.

In sum, I think impartial altruism (e.g. EA) is the result of “overgeneralising” the notion of indirect reciprocity, such that you end up wanting to help everybody everywhere.[2] And I’m skeptical a randomly drawn AI will meet the same requirements for that to happen to them.

- ^

“White-faced capuchin monkeys show triadic awareness in their choice of allies”:

″...contestants preferentially solicited prospective coalition partners that (1) were dominant to their opponents, and (2) had better social relationships (higher ratios of affiliative/cooperative interactions to agonistic interactions) with themselves than with their opponents.”

You can get allies by being nice, but not unless you’re also dominant.

- ^

For me, it’s not primarily about human values. It’s about altruistic values. Whatever anything cares about, I care about that in proportion to how much they care about it.

I like the word “leverage point”, or just “opportunity”. I wish to elicit suggestions about what kind of leverage points I could exploit to improve at what I care about. Or, the inverse framing, what are some bottlenecks wrt what I care about that I’m failing to notice? Am I wasting time overoptimising some non-critical path (this is tbh one of my biggest bottlenecks)?

That said, if somebody’s got a suggestion on their heart, I’d happier if they sent me a howler compared to no feedback at all. I regularly (while trying to keep it from getting too annoying) elicit feedback from people who might have it, in case it’s hard for them to bring it up.

That’s very kind of you, thanksmuch.

I only skimmed the post, but it was unusually usefwl for me even so. I hadn’t grokked risk from simply runaway replication of LLMs. Despite studying both evolution & AI, I’d just never thought along this dimension. I always assumed the AI had to be smart in order to be dangerous, but this is a concrete alternative.

People will continue to iteratively experiment with and improve recursive LLMs, both via fine-tuning and architecture search.[1]

People will try to automate the architecture search part as soon as their networks seem barely sufficient for the task.

Many of the subtasks in these systems explicitly involve AIs “calling” a copy of themselves to do a subtask.

OK, I updated: risk is less straightforward than I thought. While the AIs do call copies of themselves, rLLMs can’t really undergo a runaway replication cascade unless they can call themselves as “daemons” in separate threads (so that the control loop doesn’t have to wait for the output before continuing). And I currently don’t see an obvious profit motive to do so.

- ^

Genetic evolution is a central example of what I mean by “architecture search”. DNA only encodes the architecture of the brain with little control over what it learns specifically, so genes are selected for how much they contribute to the phenotype’s ability to learn.

While rLLMs will at first be selected for something like profitability, that may not remain the dominant selection criterion for very long. Even narrow agents are likely to have the ability to copy themselves, especially if it involves persuasion. And given that they delegate tasks to themselves & other AIs, it seems very plausible that failure modes include copying itself when it shouldn’t, even if they have no internal drive to do so. And once AIs enter the realm of self-replication, their proliferation rate is unlikely to remain dependent on humans at all.

All this speculation is moot, however, if somebody just tells the AI to maximise copies of itself. That seems likely to happen soon after it’s feasible to do so.

Thanks!

Although, I think many distinct spaces for small groups leads to better research outcomes for network epistemology reasons, as long as links between peripheral groups & central hubs are clear. It’s the memetic equivalent of peripatric vs parapatric speciation. If there’s nearly panmictic “meme flow” between all groups, then individual groups will have a hard time specialising towards the research niche they’re ostensibly trying to research.

In bio, there’s modelling (& some observation) suggesting that the range of a species can be limited by the rate at which peripheral populations mix with the centre.[1] Assuming that the territory changes the further out you go, the fitness of pioneering subpopulations will depend on how fast they can adapt to those changes. But if they’re constantly mixing with the centroid, adaptive mutations are diluted and expansion slows down.

As you can imagine, this homogenisation gets stronger if fitness of individual selection units depend on network effects. Genes have this problem to a lesser degree, but memes are special because they nearly always show something like a strong Allee effect[2]--proliferation rate is proportional to prevalence, but is often negative below a threshold for prevalence.

Most people are usually reluctant to share or adopt new ideas (memes) unless they feel safe knowing their peers approve of it. Innovators who “oversell themselves” by being too novel too quickly, before they have the requisite “social status license”, are labelled outcasts and associating with them is reputationally risky. And the conversation topics that end up spreading are usually very marginal contributions that people know how to cheaply evaluate.

By segmenting the market for ideas into small-world network of tight-knit groups loosely connected by central hubs, you enable research groups to specialise to their niche while feeling less pressure to keep up with the global conversation. We don’t need everybody to be correct, we want the community to explore broadly so at least one group finds the next universally-verifiable great solution. If everybody else gets stuck in a variety of delusional echo-chambers, their impact is usually limited to themselves, so the potential upside seems greater. Imo. Maybe.

Super post!

In response to “Independent researcher infrastructure”:

I honestly think the ideal is just to give basic income to the researchers that both 1) express an interest in having absolute freedom in their research directions, and 2) you have adequate trust for.

I don’t think much valuable gets done in the mode where people look to others to figure out what they should do. There are arguments, many of which are widely-known-but-not-taken-seriously, and I realise writing more about it here would take more time than I planned for.

Anyway, the basic income thing. People can do good research on 30k USD a year. If they don’t think that’s sufficient for continuing to work on alignment, then perhaps their motivations weren’t on the right track in the first place. And that’s a signal they probably weren’t going to be able to target themselves precisely at what matters anyway. Doing good work on fuzzy problems requires actually caring.