LessWrong dev & admin as of July 5th, 2022.

RobertM

Animal welfare concerns are dominated by post-ASI futures

Yes, indeed, there was only an attempt to hide the post three weeks ago. I regret the sloppiness in the details of my accusation.

The other false accusation was that I didn’t cite any sources

I did not say that you did not cite any sources. Perhaps the thing I said was confusingly worded? You did not include any links to any of the incidents that you describe.

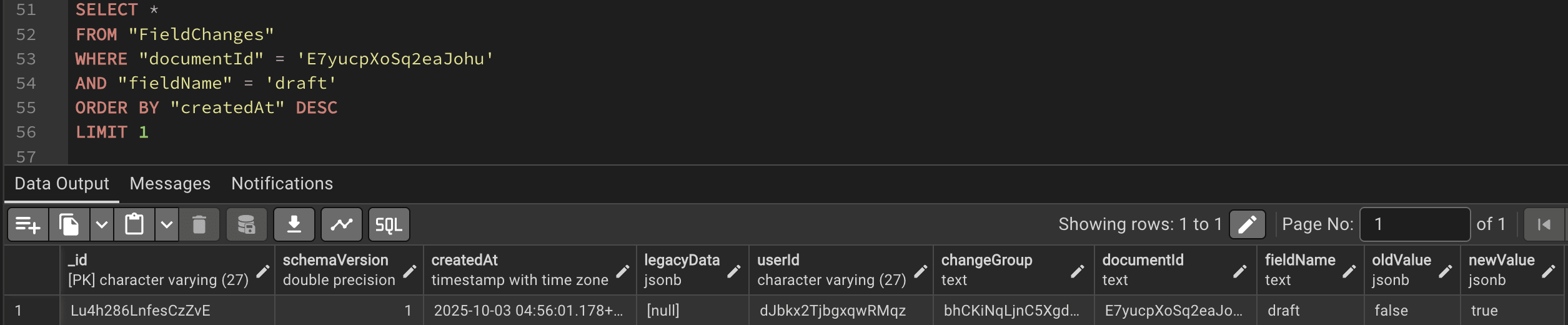

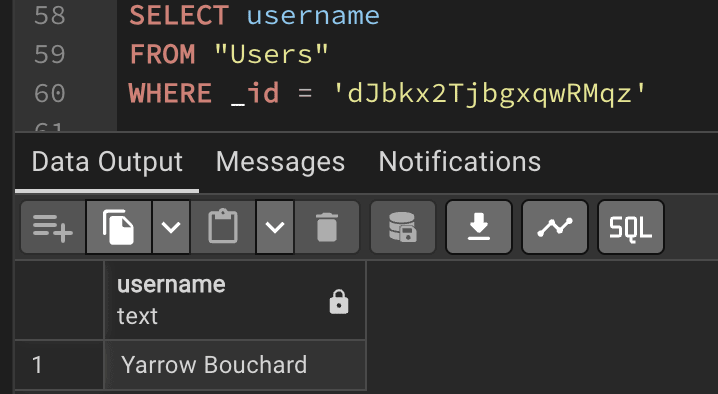

My bad, it was moved back to draft on October 3rd (~3 weeks ago) by you. I copied the link from another post that linked to it.

It’s really quite something that you wrote almost 2000 words and didn’t include a single primary citation to support any of those claims. Even given that most of them are transparently false to anyone who’s spent 5 minutes reading either LW or the EA Forum, I think I’d be able to dig up something superficially plausible with which to smear them.

And if anyone is curious about why Yarrow might have an axe to grind, they’re welcome to examine this post, along with the associated comment thread.

Edit: changed the link to an archive.org copy,

since the post was moved to draft after I posted this.Edit2: I was incorrect about when it was moved back to a draft, see this comment.

I’m probably a bit less “aligned ASI is literally all that matters for making the future go well” pilled than you, but it’s definitely a big part of it.

Sure, but the vibe I get from this post is that Will believes in that a lot less than me, and the reasons he cares about those things don’t primarily route through the totalizing view of ASI’s future impact. Again, I could be wrong or confused about Will’s beliefs here, but I have a hard time squaring the way this post is written with the idea that he intended to communicate that people should work on those things because they’re the best ways to marginally improve our odds of getting an aligned ASI. Part of this is the list of things he chose, part of it is the framing of them as being distinct cause areas from “AI safety”—from my perspective, many of those areas already have at least a few people working on them under the label of “AI safety”/”AI x-risk reduction”.

Like, Lightcone has previously and continues to work on “AI for better reasoning, decision-making and coordination”. I can’t claim to speak for the entire org but when I’m doing that kind of work, I’m not trying to move the needle on how good the world ends up being conditional on us making it through, but on how likely we are to make it through at all. I don’t have that much probability mass on “we lose >10% but less than 99.99% of value in the lightcone”[1].

Edit: a brief discussion with Drake Thomas convinced me that 99.99% is probably a pretty crazy bound to have; let’s say 90%. Wqueezing out that extra 10% involves work that you’d probably describe as “macrostrategy”, but that’s a pretty broad label.

- ^

I haven’t considered the numbers here very carefully.

- ^

I don’t think that—animal welfare post-ASI is a subset of “s-risks post-ASI”.

If you’ve got a very high probability of AI takeover (obligatory reference!), then my first two arguments, at least, might seem very weak because essentially the only thing that matters is reducing the risk of AI takeover.

I do think the risk of AI takeover is much higher than you do, but I don’t think that’s why I disagree with the arguments for more heavily prioritizing the list of (example) cause areas that you outline. Rather, it’s a belief that’s slightly upstream of my concerns about takeover risk—that the advent of ASI almost necessarily[1] implies that we will no longer have our hands on the wheel, so to speak, whether for good or ill.

An unfortunate consequence of having beliefs like I do about what a future with ASI in it involves is that those beliefs are pretty totalizing. They do suggest that “making the transition to a post-ASI world go well” is of paramount importance (putting aside questions of takeover risk). They do not suggest that it would be useful for me to think about most of the listed examples, except insofar as they feed into somehow getting a friendly ASI rather than something else. There are some exceptions: for example, if you have much lower odds of AI takeover than I do, but still expect ASI to have this kind of totalizing effect on the future, I claim you should find it valuable for some people to work on “animal welfare post-ASI”, and whether there is anything that can meaningfully be done pre-ASI to reduce the risk of animal torture continuing into the far future[2]. But many of the other listed concerns seem very unlikely to matter post-ASI, and I don’t get the impression that you think we should be working on AI character or preserving democracy as instrumental paths by which we reduce the risk of AI takeover, bad/mediocre value lock-in, etc, but because you consider things like that to be important separate from traditional “AI risk” concerns. Perhaps I’m misunderstanding?

- ^

Asserted without argument, though many words have been spilled on this question in the past.

- ^

It is perhaps not a coincidence that I expect this work to initially look like “do philosophy”, i.e. trying to figure out whether traditional proposals like CEV would permit extremely bad outcomes, looking for better alternatives, etc.

- ^

I agree that titotal should probably not have used the word “bad” but disagree with the reasoning. The problem is that “bad” is extremely nonspecific; it doesn’t tell the reader what titotal thinks is wrong with their models, even at a very low resolution. They’re just “bad”. There are other words that might have been informative, if used instead.

Of course, if he had multiple different kinds of issues with their models, he might have decided to omit adjectives from the title for brevity’s sake and simply explained the issues in the post. But if he thought the main issue was (for the sake of argument) that the models were misleading, then I think it would be fine for him to say that in the title.

If I’m understanding your question correctly, that part of my expectation is almost entirely conditional on being in a post-ASI world. Before then, if interest in (effectively) reducing animal suffering stays roughly the size of “EA”, then I don’t particularly expect it to be become cheap enough to subsize people farming animals to raise them in humane conditions. (This expectation becomes weaker with longer AI timelines, but I haven’t though that hard about what the world looks like in 20+ years without strong AI, and how that affects the marginal cost of various farmed animal welfare interventions.)

So my timelines on that are pretty much just my AI timelines, conditioned on “we don’t all die” (which are shifted a bit longer than my overall AI timelines, but not by that much).

Yudkowsky explicitly repudiates his writing from 2001 or earlier:

You should regard anything from 2001 or earlier as having been written by a different person who also happens to be named “Eliezer Yudkowsky”. I do not share his opinions.

that is crying wolf today

This is assuming the conclusion, of course.

and ask them if they are trying to get loans in order to increase their donations to projects decreasing AI risk, which makes sense if they do not expect to pay the interest in full due to high risk of extinction.

Fraud is bad.

In any case, people already don’t have enough worthwhile targets for donating money to, even under short timelines, so it’s not clear what good taking out loans would do. If it’s a question of putting one’s money where one’s mouth is, I personally took a 6-figure paycut in 2022 to work on reducing AI x-risk, and also increased my consumption/spending.

Post-singularity worlds where people have the freedom to cause enormous animal suffering as a byproduct of legacy food production methods, despite having the option to not do so fully subsidized by third parties, seem like they probably overlap substantially with worlds where people have the freedom to spin up large quantities of digital entities capable of suffering and torture them forever. If you think such outcomes are likely, I claim that this is even more worthy of intervention. I personally don’t expect to have either option in most post-singularity worlds where we’re around, though I guess I would be slightly less surprised to have the option to torture animals than the option to torture ems (though I haven’t thought about it too hard yet).

But, as I said above, if you think it’s plausible that we’ll have the option to continue torturing animals post-singularity, this seems like a much more important outcome to try to avert than anything happening today.

I think you misunderstood my framing; I should have been more clear.

We can bracket the case where we all die to misaligned AI, since that leads to all animals dying as well.

If we achieve transformative AI and then don’t all die (because we solved alignment), then I don’t think the world will continue to have an “agricultural industry” in any meaningful sense (or, really, any other traditional industry; strong nanotech seems like it ought to let you solve for nearly everything else). Even if the economics and sociology work out such that some people will want to continue farming real animals instead of enjoying the much cheaper cultured meat of vastly superior quality, there will be approximately nobody interested in ensuring those animals are suffering, and the cost for ensuring that they don’t suffer will be trivial.

Of course, this assumes we solve alignment and also end up pointed in the right direction. For a variety of reasons it seems pretty unlikely to me that we manage to robustly solve alignment of superintelligent AIs while pointed in “wrong”[1] directions; that sort of philosophical unsophistication is why I’m pessimistic on our odds of success. But other people disagree, and if you think it’s at all plausible that we achieve TAI in a way that locks in reflectively-unendorsed values which lead to huge quantities of animal suffering, that seems like it ought to dominate effectively all other considerations in terms of interventions w.r.t. future animal welfare.

- ^

Like those that lead to enormous quantities of trivially preventable animal suffering for basically dumb contingent reasons, i.e. “the people doing the pointing weren’t really thinking about it at the time, and most people don’t actually care about animal suffering at all in most possible reflective equilibria”.

- ^

Is this post conditioning on AI hitting a wall ~tomorrow, for the next few decades? The analysis seems mostly reasonable, if so, but I think the interventions for ensuring that animal welfare is good after we hit transformative AI probably look very different from interventions in the pretty small slice of worlds where the world looks very boring in a few decades.

This is a bit of a sidenote, but while it’s true that “LWers” (on average) have a different threshold for how valuable criticism needs to be to justify its costs, it’s not true that “we” treat it as a deontic good. Observe, as evidence, the many hundreds of hours that various community members (including admins) have spent arguing with users like Said about whether their style of engagement and criticism was either effective at achieving its stated aims, or even worth the cost if it was[1]. “We” may have different thresholds, but “we” do not think that all criticism is necessarily good or worth the attentional cost.

The appropriate threshold is an empirical question whose answer will vary based on social context, people, optimization targets, etc.

Object-level, I probably agree that EA spends too much of its attention on bad criticism, but I also think it doesn’t allocate enough attention to good criticism, and this isn’t exactly the kind of thing that “nets out”. It’s more of a failure of taste/caring about the right things, which is hard to fix by adjusting the “quantity” dial.

- ^

He has even been subjected to moderation action more than once, so the earlier claim re: gadflies doesn’t stand up either.

- ^

No easily summarizable comment on the rest of it, but as a LessWrong dev I do think the addition of Quick Takes to the front page of LW was very good—my sense is that it’s counterfactually responsible for a pretty substantial amount of high quality discussion. (I haven’t done any checking of ground-truth metrics, this is just my gestalt impression as a user of the site.)

My claim is something closer to “experts in the field will correctly recognize them as obviously much smarter than +2 SD”, rather than “they have impressive credentials” (which is missing the critically important part where the person is actually much smarter than +2 SD).

I don’t think reputation has anything to do with titotal’s original claim and wasn’t trying to make any arguments in that direction.

Also… putting that aside, that is one bullet point from my list, and everyone else except Qiaochu has a wikipedia entry, which is not a criteria I was tracking when I wrote the list but think decisively refutes the claim that the list includes many people who are not publicly-legible intellectual powerhouses. (And, sure, I could list Dan Hendryks. I could probably come up with another twenty such names, even though I think they’d be worse at supporting the point I was trying to make.)

This still feels wrong to me: if they’re so smart, where are the nobel laureates? The famous physicists?

I think expecting nobel laureates is a bit much, especially given the demographics (these people are relatively young). But if you’re looking for people who are publicly-legible intellectual powerhouses, I think you can find a reasonable number:

Wei Dai

Hal Finney (RIP)

Scott Aaronson

Qiaochu Yuan[1]

Many historical MIRI researchers (random examples: Scott Garrabrant, Abram Demski, Jessica Taylor)

Paul Christiano (also formerly did research at MIRI)

(Many more not listed, including non-central examples like Robin Hanson, Vitalik Buterin, Shane Legg, and Yoshua Bengio[2].)

And, like, idk, man. 130 is pretty smart but not “famous for their public intellectual output” level smart. There are a bunch of STEM PhDs, a bunch of software engineers, some successful entrepreneurs, and about the number of “really very smart” people you’d expect in a community of this size.

- ^

He might disclaim any current affiliation, but for this purpose I think he obviously counts.

- ^

Who sure is working on AI x-risk and collaborating with much more central rats/EAs, but only came into it relatively recently, which is both evidence in favor of one of the core claims of the post but also evidence against what I read as the broader vibes.

This is made up, as far as I can tell (at least re: symbolic AI as described in the wikipedia article you link). See Logical or Connectionist AI? (2008):

Wikipedia, on GOFAI (reformatted, bolding mine):

Even earlier is Levels of Organization in General Intelligence. It is difficult to excerpt a quote but it is not favorable to the traditional “symbolic AI” paradigm.

I really struggle to see how you could possibly have come to this conclusion, given the above.

And see here re: Collier’s review.