I recently completed a PhD exploring the implications of wild animal suffering for environmental management. You can read my research here: https://scholar.google.ch/citations?user=9gSjtY4AAAAJ&hl=en&oi=ao

I am now considering options in AI ethics, governance, or the intersection of AI and animal welfare.

Tristan Katz

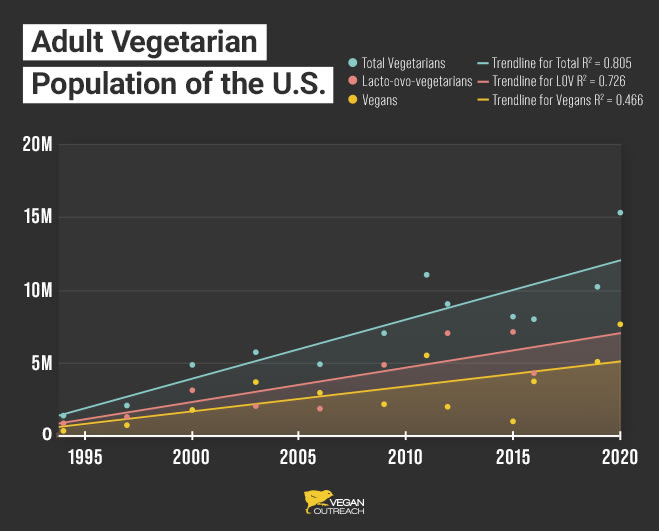

stagnant levels of veganism over the past few decades (between 1%-5%

I don’t think this is true. It would be true if you talked about the last one decade—survey results seem to show a pretty clear fluctuation, rather than rise. But I’m afraid that EAs are over-updating because of this. Although survey data is more patchy before that, they show a pretty remarkable rise in veganism over my lifetime (i.e. 30 years) and I definitely see that in my own life.

I agree with all of this. But does this mean your answer is: yes, in most cases we should treat veganism as a moral baseline? Since the norms you say we should push for (plan-based, avoiding animal testing) do seem to entail veganism. I can imagine this varying by context—pushing for these norms might mean treating veganism as a baseline for advocates in Germany, but maybe not in Spain or China*, given that it’s just way harder to follow those norms strictly there.

*Countries chosen based on my ignorant perception of them

Thanks a lot for this!

If you are a UK resident/citizen you can fill in the consultation:

The form itself doesn’t seem to require any evidence for either. Just...pointing that out.

Hey Mal, this is a great point, I completely agree. The disease doesn’t have to be worse than all possible ways of dying if you know that the counterfactual is likely to be a particular mid-intensity harm. Although the welfare gains should still be significant in order to justify the ecological risks.

Oh I see I’d misunderstood your point. I thought you were concerned about lowering the number of warble flies. This policy wouldn’t lower the number of deer—it would maintain the population at the same level. This is for the sake of avoiding unwanted ecological effects. If you think it’s better to have more deer, fair enough—but then you’ve got to weigh that against the very uncertain ecological consequences of having more deer (probably something like what happened in Yellowstone Nationa Park: fewer young trees, more open fields, fewer animals that depend on those trees, more erosion etc)

No—and I wasn’t meaning to say that less beings with higher welfare is always better. Like I said, I don’t think the common sense view will be philosophically satisfying.

But a second common sense view is: if there are some beings whose existence depends on harming others, then them not coming into existence is preferable.

I expect you can find some counter-example to that, but I think most people will believe this in most situations (and certainly those involving parasites).

You’re right that this is philosophically controversial. I find the debate interesting, and don’t mean to dismiss it—but I also find it incredibly difficult.

The challenge I see is whether such philosophical debates, ones that are totally unresolved, should inform our practical thinking and policy recommendations. Because within ordinary, day-to-day thinking, the idea that “it’s preferable to have more beings with lower welfare” is controversial. If you were committed to this view, and thought insects have positive welfare (I agree with @Jim Buhler that this isn’t clear), then it seems you would also have to say that the Against Malaria Foundation is doing overall bad work. Maybe you’re willing to bite that bullet—but my own inclination is to assume a more common-sense view, even if philosophically incoherent, until there is something closer to a consensus on this topic.

Thanks Michael! And definitely, all of these interventions should ideally be pursued only after trying to predict as many of the effects as possible. I gave a bit more of an answer on this point below.

I can also imagine incrementally moving down the ladder of worst harms… but I expect things will get harder as interventions become more pervasive, and at some point we would need more comprehensive modelling or to really think about how we want to shape the ecosystem as a whole.

Thanks for this point!

My argument is that while such outcomes are possible, the outcomes of the opposite effect are also possible, and often there just doesn’t seem reason to assume one to be more likely than the other (this is in simplest terms what people mean when they talk about cluelessness). Given that, I think it makes sense to assume the effects which we cannot predict are on expectation neutral (most likely, they will be a mix of good and bad) and then pursue it if the effects we can predict are clearly good.

So for example, treating chronic wasting disease in deer will surely affect populations of very small mammals, reptiles, and insects in subtle but nonetheless large ways, due to the numbers of these species. But it’s going to be a mix of benefits and harms, which are incredibly hard to predict. The benefit for the deer, however, is really certain, so if it can be done without great environmental disruption, then I’d say the expected value is pretty good.

Thanks Diego!

Yea, I largely disregarded political/cultural tractability in this analysis, as well as cost. So while I would LOVE to see ecological islands created for animal welfare, this would be prohibitively expensive for activists, and it’s hard to imagine governments deciding to do it anytime soon. I think the main purpose of the paper was to show that positive WAW interventions are feasible (and desirable) in the near-term future, even if still all-things-considered unlikely.

That said, I think the other interventions would be easier on this dimensions. Most ordinary people do sympathize with animals suffering particularly severe diseases or nasty parasites. We don’t place as much value on these the way we do for other species. So if this could be shown to be cheap, I think people might support it, particularly if it were part of a rewilding project (where people think they have more responsibility for the animals) or also affect farm animals. So to be clear, I do think the work of Screwworm Free Future is a great idea and totally worth pursuing!

Similarly, people seem to sympathize with urban animals a lot more, and we already see urban planning projects taking animal welfare into account (I think that dovecotes used to reduce urban pigeon reproduction, for example, are very likely to improve welfare).

And for promoting high-welfare ecosystems… this would be tractable if it was something people were tempted to do for other reasons. For example, if desert greening improves welfare, then we should encourage desert greening. If it doesn’t, then we can leverage reasons for opposing it e.g. it not being natural.

At the end of the day, I think the main bottleneck is just that we’re not trying enough things (but I think Rethink Priorities is looking to change this).

Improving wild animal welfare reliably

It seems like the wrong framing to talk about a “positive vision” for the transition to superintelligence, if that transition involves immense risks and is generally a bad idea. If you think the transition could be “on a par with the evolution of Homo sapiens, or of life itself” but compressed into years, then that surely involves immense risks (of very diverse kinds!).

From what I’ve heard you say elsewhere, I think you basically agree with this. But then, surely you must agree that the priority is to delay this process until we can make sure it’s safe and well-controlled. And if you are going to talk about positive visions, then I would say it’s really important that such visions come with an explicit disclaimer that they are talking about a future we should be actively trying to avoid. I’m afraid that otherwise these articles might give people the wrong idea.

Edit: to make my point clearer, I think a good analogy would be to think of yourself right before the development of nuclear power (including the nuclear bomb). Suppose other people are already talking about the risks, and it seems it’s likely to happen so maybe it’s worth thinking about how we can make a good future with nuclear. Ok. But given the risks (and that many people still aren’t aware of them), talking about a good nuclear future without flagging that the best course of action would be to delay developing this technology until we’re sure we can avoid catastrophe seems like a potential infohazard.

I think a big challenge is that often different interventions appear better or worse depending on the time horizon. That’s apparent in this case: if corporate campaigns get a dozen companies to commit to buying cage-free eggs, that will have benefits in a matter of years. It’s not clear what the long-term impacts will be (maybe a changing corporate culture that becomes more conscious of animal welfare? Maybe higher prices, leading to lower consumption of animal products?) but the theory of change isn’t normally spelled out over that time horizon. For alternative proteins, the short-term benefits are rather modest, and the much more important benefits seem long-term, if it can lead to a much bigger plant-based market, there’s a high chance that people will be more willing to consider changing their diet (and their ethics) completely.

I would really like to see more long-term theories of change within animal advocacy. I even find it a bit odd that it isn’t more normal, given the buzz around longtermism within EA.

To be clear, my reason for disgust isn’t because I think that eating meat is impure. It’s because seeing dead animals, or parts of dead animals, reminds me of the life that once existed and is now gone. This is the same reason for why I would never be appetized by human flesh—seeing dead people fills me with sorrow, and seeing many dead people in places where dead people shouldn’t be (such as on supermarket shelves) fills me with horror, because it reminds me of the atrocity that continues.

Many vegetarians don’t have these emotions because they haven’t fully recognized the atrocity for what it is. They aren’t really coming to terms with the scale of suffering. Many vegans don’t either, but I don’t think it’s possible to really be cognizant of the atrocity for what it is and not have this emotional reaction, for most people. For this reason, I want to be horrified, disgusted by meat, because I don’t want to ignore the scale of the suffering around me. I want to be aware of and motivated by this wrong (except of course it is overwhelming and counterproductive). And I’m referring to myself here, but I think we would have much more pro-animal action if other people also tried to internalize nonspeciesm in this way too.

I hope that makes sense.

Sorry I missed this comment when you originally made it.

These are good arguments, but I disagree that you’re hitting the same benefits. They’re the same kind of reasons for adopting that diet, but the benefits are different:Even if you consider your empathy ‘sufficient’, it’s not clear you’re feeling the same empathy. Speaking anecdotally: I went vegetarian and vegan gradually, bit by bit, and I know that something clicked in my mind when I gave up meat altogether. If you really cared about other animals and saw them as conscious beings, you should be disgusted by meat, in a similar way to how you would feel about eating human meat. You should be horrified—at least, if your emotions work the way they do for most humans. So assuming that you’re not highly neurodivergent in a way that makes you the exception to this rule, I assume that you’re not empathising with animals at the same level. This has implications for how you do cause prioritisation, where you donate, what career you choose etc.

You’re giving a different social signal (that eating chicken is wrong, rather than eating meat is wrong).

I’ll agree with the third point, not eating chicken is clearly easier.

Regarding the last point, I would agree… except that supply of meat is increasing, both globally and in the west. Efforts to change the minds of individual people aren’t working, and won’t work as long as structural issues e.g. the subsidisation of meat continue.

Hey Arnold, thanks for the message. Hmm do I understand the question correctly as: if I’m optimising for impact, but wary of burnout, I want to donate as much as possible without lowering my standard of living to an unsustainable level? And you’re saying what’s personally satisfying might not be the best thing?

That’s certainly true. I’m almost sure that I could do more. I suppose I’m just wary of trying to optimise too much, because I think it can be emotionally draining. To be honest I think that social factors can be really important for this though—I would be willing to try to optimise more if those around me were doing it more. But I’m not really sure if that responded to your question!

My intention would be to gradually increase. So in the past I was earning just slightly above the median, but gave 15%. In general I think it’s good to have an idea of what income you’re comfortable with, and then increase donations significantly as you pass that point. But I set the bar really high here just because I’m aware that my perception of what is enough might change in different life-stages.

To be honest I think my model is super crude and probably not ideal, I would really like to see other models like this!

Hey, totally agree that the sentiment isn’t always helpful—it’s one that motivates me, but it’s definitely not what I say in my elevator pitch to encourage others to donate!

Like others I find the question to present a false dichotomy.

Similarly, I find it much easier to take someone’s commitment to animal advocacy seriously if they’re vegan, and I think it’s the best way to be internally consistent with your morals. I also think that anyone who is buying meat is contributing to harm, even if they offset. In that sense it’s a ‘baseline’, but I still think offsetting is good, and I don’t want to exclude anyone from being animal advocates, because I know veganism is hard and people are motivated by different things.

I think of it like anti-smoking campaigns: smoking is not good. If you donate and smoke, well that’s good overall but still I’d rather you didn’t smoke. And your smoking shouldn’t stop you from being able to fight the tobacco lobby!

So: yes, a baseline, but not a requirement. Offsetting is good, but not a legitimate stopping point.