How Could AI Governance Go Wrong?

(I gave a talk to EA Cambridge in February 2022. People have told me they found it useful as an introduction/overview so I edited the transcript, which can be found below. If you’re familiar with AI governance in general, you may still be interested in the sections on ‘Racing vs Dominance’ and ‘What is to be done?’.)

Talk Transcript

I’ve been to lots of talks which catch you with a catchy title and they don’t actually tell you the answer until right at the end so I’m going to skip right to the end and answer it. How could AI governance go wrong?

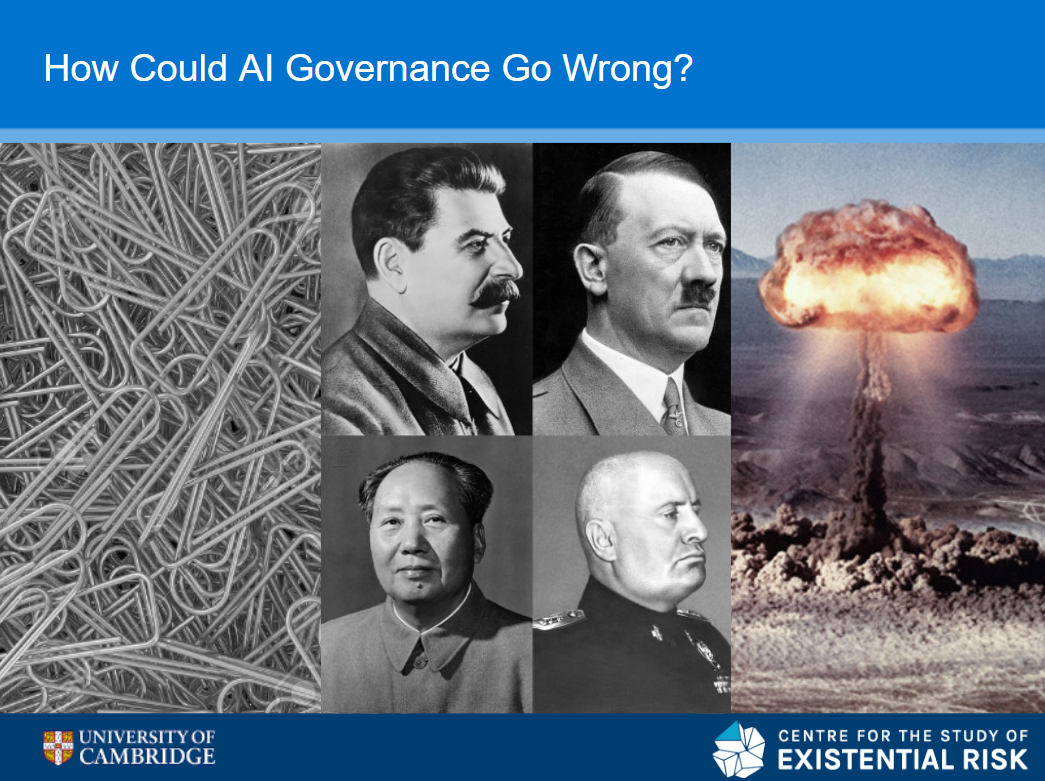

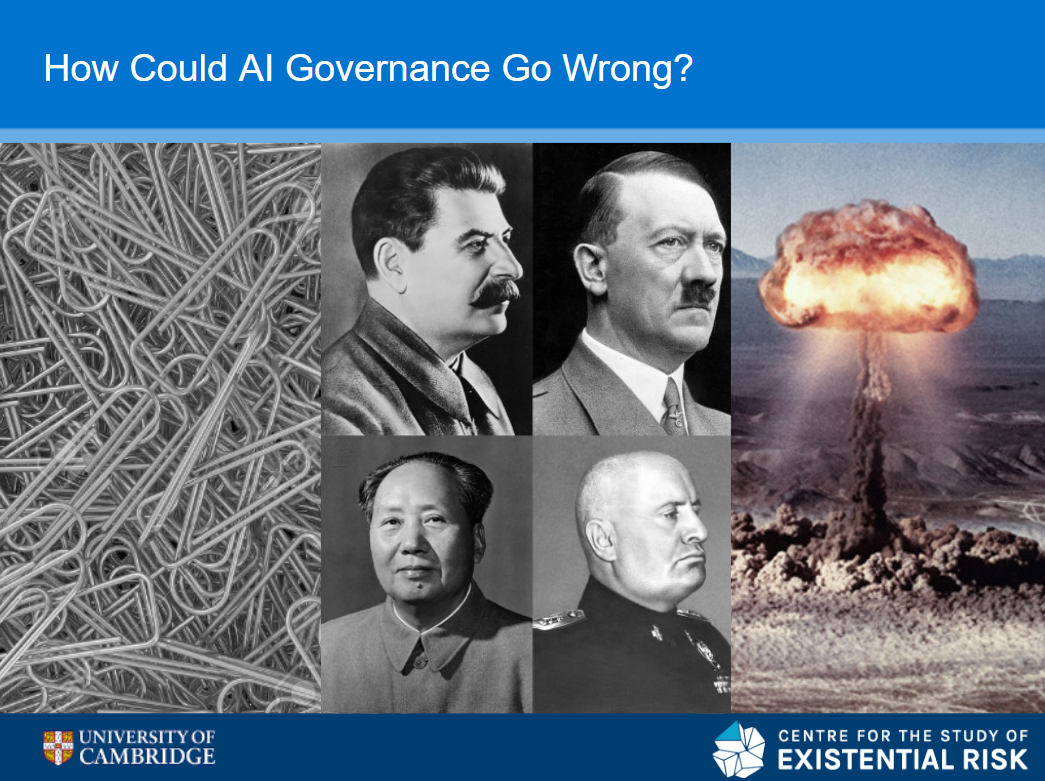

These are the three answers that I’m gonna give: over here you’ve got some paper clips, in the middle you’ve got some very bad men, and then on the right you’ve got nuclear war. This is basically saying the three cases are accident, misuse and structural or systemic risks. That’s the ultimate answer to the talk, but I’m gonna take a bit longer to actually get there.

I’m going to talk very quickly about my background and what CSER (the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk) is. Then I’m going to answer what is this topic called AI governance, then how could AI governance go wrong? Before finally addressing what can be done, so we’re not just ending on a sad glum note but we’re going out there realising there is useful stuff to be done.

My Background & CSER

This is an effective altruism talk, and I first heard about effective altruism back in 2009 in a lecture room a lot like this, where someone was talking about this new thing called Giving What We Can, where they decided to give away 10% of their income to effective charities. I thought this was really cool: you can see that’s me on the right (from a little while ago and without a beard). I was really taken by these ideas of effective altruism and trying to do the most good with my time and resources.

So what did I do? I ended up working for the Labour Party for several years in Parliament. It was very interesting, I learned a lot, and as you can see from the fact that the UK has a Labour government and is still in the European Union, it went really well. Two of the people I worked for are no longer even MPs. After this sterling record of success down in Westminster – having campaigned in one general election, two leadership elections and two referendums – I moved up to Cambridge five years ago to work at CSER.

The Centre for the Study of Existential Risk: we’re a research group within the University of Cambridge dedicated to the study and mitigation of risks that could lead to human extinction or civilizational collapse. We do high quality academic research, we develop strategies for how to reduce risk, and then we field-build, supporting a global community of people working on existential risk.

We were founded by these three very nice gentlemen: on the left that’s Prof Huw Price, Jaan Tallinn (founding engineer of Skype and Kazaa) and Lord Martin Rees. We’ve now grown to about 28 people (tripled in size since I started) - there we are hanging out on the bridge having a nice chat.

A lot of our work falls into four big risk buckets:

pandemics (a few years ago I had to justify why that was in the slides, now unfortunately it’s very clear to all of us)

AI, which is what we’re going to be talking mainly about today

climate change and ecological damage, and then

systemic risk from all of our intersecting vulnerable systems.

Why care about existential risks?

Why should you care about this potentially small chance of the whole of humanity going extinct or civilization collapsing in some big catastrophe? One very common answer is looking at the size of all the future generations that could come if we don’t mess things up. The little circle in the middle is the number of currently alive people. At the top is all the previous generations that have gone before. This much larger circle is the number of unborn generations there could be (if population growth continues at the same rate as this century for 50,000 more years). You can see there’s a huge potential that we have in front of us. These could all be living very happy, fulfilling, flourishing lives and yet they could potentially go extinct. They could never come to be. This would be a terrible end to the human story, just a damp squib. That’s a general argument for why a lot of us are motivated to work on existential risk, but it’s not the only argument.

I put this together a little while ago. These are three intersecting circles. At the top is the idea of longtermism or future generations, with the slogan “future generations matter morally”. There’s existential risk: “humanity could go extinct to lose its potential”. Third there’s effective altruism, this idea of “doing the most good with reason and evidence”

The point is that while they intersect (and I would place myself in the middle) you don’t have to believe in one to be sold on the other. There’s lots of good existential risk researchers who are not so convinced about the value of the future but still think it’ll be so terrible for the current generation that it’s worth doing a lot about. There’s a lot of different ways you can come to this conclusion that existential risk is really important.

So that is a bit of a background on why I’m interested in this, what CSER does and why we’re working on this these risks.

What’s AI governance?

This is the only slide with this much text, so you’ll forgive me just reading it out (because it’s a definition and we’re academics we like definitions). AI governance is “the study or practice of local and global governance systems including norms policies laws processes and institutions that govern or should govern AI research, development, deployment and use”.

‘By deployment’, I mean that you may develop and train an AI system—but then using it in the world is often referred to as deployment. This definition is from some of my colleagues. I think it’s good because it’s a very broad definition of AI governance and what we’re doing when we do AI governance. But who does AI governance?

Here are six people who I’m going to say all do all work on AI governance:

Timnit Gebru, who was a researcher at Google, wrote a paper that criticized some of the large language models that Google was developing, got fired for it and has now left and started her own research group. She works on AI governance.

Sheryl Sandberg, who’s number two at Facebook/Meta. She’s a very important person in deciding what Facebook’s recommender systems (an AI system) pushes in front of various people (e.g. what teenagers see on Instagram). She works on AI governance.

Margrethe Vestager is the European Commissioner for Competition Law and also does a lot on digital markets. She has brought some really big cases against big tech companies and she’s a key figure behind the EU’s current AI Act which regulates high risk ai systems. She works on AI governance.

Lina Khan. When she was an academic she wrote a great paper called Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox and she just got appointed to be chair of the Federal Trade Commission by the Biden administration. She works on AI governance.

Avril Haines. She’s now the US Director of National Intelligence but before the election she wrote a great paper on how AI systems could get incorporated safely and ethically into defense. She works on AI governance.

Finally this is Meredith Whitaker, she also worked at Google. She was one of the core organizers of the Google Walkout for Real Change which was protested the treatment of people who have reported sexual harassment. She also has left google. She founded the AI Now Institute, an important research NGO. She works on AI governance.

What I’m trying to convey here is there’s lots of different sides to AI governance: from different countries; within companies, government, academia, NGOs; from the military side from the civilian side. It’s a broad and interesting topic. That’s the broad field of AI governance.

I’m going to zoom in a little bit more to where I spend a lot of my time, which is more on long-term governance. We’ve got three photos of three conferences organized by the Future of Life Institute called the Beneficial AGI conferences. The first one in 2015, the second one is 2017, and this last one down here (I’m in at the back) was in 2019. These were three, big, important conferences that brought a lot of people together to discuss the safe and beneficial use of AI. This first one in 2015 led to an Open Letter signed by 8,000 robotics and AI researchers calling for the safe and beneficial use of AI and releasing this research agenda alongside it. It really placed this topic on the agenda – a big moment for the field. This next one project was in 2017 in Asilomar and it produced the Asilomar AI Principles, one of the first and most influential (I would say) of the many AI ethics principles that have come out in recent years. The last one really got into more of the nuts and bolts of what sort of policies and governance systems there should be around AI governance.

The idea of these three pictures is to show you that in 2015 this thing was still getting going. Starting to say “I want to develop ai safely and ethically” was a novel thing. In 2017 there was this idea of “maybe we should have principles” and then by 2019 this had turned into more concrete discussions. Obviously, there wasn’t one in 2021 and we can all maybe hope for next year.

That’s my broad overview of the kinds of things that people who work on AI governance work on and a bit of how the field’s grown.

How could AI governance go wrong? General argument: this could be a big deal

This is a survey by YouGov. They surveyed British people in 2016 and again in 2022 on what are the most likely causes of future human extinction. Right up at the top there’s nuclear war, global warming/climate change and a pandemic. Those three seem to make sense, it’s very understandable why those would be placed so high up by the British public. But if you see right down at the bottom nestled between a religious apocalypse and an alien invasion is robots and artificial intelligence. This is clearly not a thing that most randomly surveyed British people would place in the same category as nuclear war, pandemics or climate change. So why is it that our Centre does a lot of work on this? Why do we think that AI governance is such an important topic that it ranks up there with these other ways that we could destroy our potential?

Here’s the general argument: AI’s been getting much better recently, and it looks like it’s going to continue getting much better.

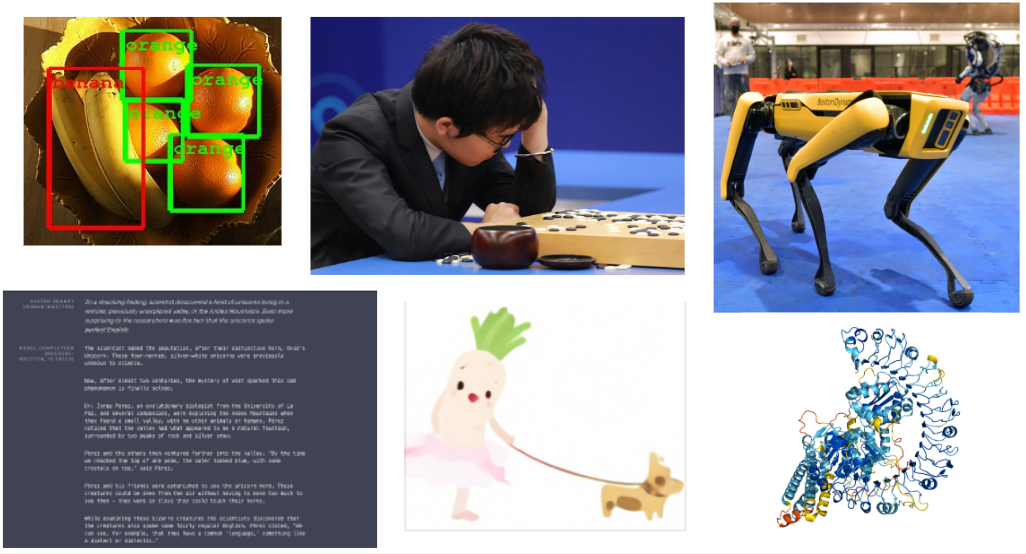

In 2012 there was a big breakthrough in image recognition where AlexNet made a huge jump in the state of the art.

This next picture represents games: Lee Sedol losing at Go to AlphaGo.

The top right is robotics, one of the Boston Dynamics dogs. Robotics has not been improving as much as the others but has still been making breakthroughs.

Bottom left here is from GPT-3. They gave it a prompt about “explorers have just found some unicorns in the Andes” and it gave this very fluent news article about it, that almost looked like it was written by humans. This is now being rolled out and you can use this language model to complete lots of different writing tasks or to answer questions in natural language with correct answers.

The next one here: they gave DALL-E a prompt of “a radish in a tutu walking a dog” and the AI system produced this remarkable illustration.

Then the final one is AlphaFold, DeepMind’s new breakthrough on protein folding. This is a very complex scientific problem that has been unsolved for lots of years and it’s now almost superhuman.

So: image recognition, games, robotics, language models generating image and text and then helping with scientific advancements. AI has been rapidly improving over the last 10 years and potentially could continue to have this very rapid increase in capabilities in the coming decades

But maybe we should think a bit more about this.

On the left here we’ve got an internal combustion engine, in the middle we’ve got the steam engine, and on the right we’ve got the inside of a fusion tokamak (which can be thought of as a type of engine). The idea is that the internal combustion engine is representative of a general purpose technology, the steam engine is representative of a transformative technology, and this fusion one is representative of the claim made by Holden Karnofsky: that we may be living in the most important century for human history.

Is AI a general purpose technology, something like the internal combustion engine, electricity, refrigeration or computers: a generally useful technology that is applied in lots of different application areas across economy and society, has many different effects on politics, military and security issues and spawns lots of further developments? I think most people would already accept that AI is already a general purpose technology at the level of these others.

Could it be a transformative technology? This term refers to something that changes civilization and our societies in an even more dramatic way. There have been two big transformative occasions in human history (zooming really really far out). First, everyone was hunter-gatherers and foragers and then the invention of farming, sometimes called the Neolithic Revolution, just transformed our entire societies, the way we live and operate in the world.

The next thing at that sort of scale is the Industrial Revolution. Especially if you look at economic growth per capita, it is basically flat since the Neolithic Revolution: it increases a bit but economic growth is Malthusian and is all eaten up by population increases. But then GDP per capita really shoots up with the Industrial Revolution and James Watts’ steam engine. There’s some possibility that AI is not just a general purpose technology but is transformative at this scale. If much of our economy, society, politics and militaries are automated then it could be a similar situation. Before the Industrial Revolution 98% of the population worked in farming and now in the UK only 2% are farmers. It could be that scale of transformation.

But then there’s this further claim that maybe it’s even a step beyond that: the most important century. The reason I chose this picture isn’t (just) because it’s an interesting picture, it’s because researchers recently applied machine learning to better control the flow of plasma around a fusion engine, much better than we’ve been able to before. This highlights the idea that AI could be used to increase the progress of science and technology itself. It’s not just that there’s new inventions happening and changing economy and society, but it’s that that process itself is being automated, sped up and increased.

AlphaFold for biotechnology and then here for physics – these are indications of how things could go. Karnofsky calls this a process for automating science and technology (PASTA). The argument is that if that takeoff were to happen sometime in this century, then this could be a very important moment. We could make new breakthroughs and have an incredible scale of economic growth and scientific discovery, much quicker even than the industrial revolution

To step back a second what I’m trying to show here is just that AI could be a very big deal and therefore how we govern it, how we incorporate it into our societies, could be also a very big deal.

How could AI governance go wrong? Specific arguments: accident, misuse and structure

| Accident | Misuse | Structure | |

| Near term | Concrete Problems | Malicious Use of AI | Flash Crash → Flash War |

| Long term | Human Compatible | Superintelligence | ‘Thinking About Risks From AI’ |

But how could it go wrong? The risk is generally split into accident, misuse and structure (following a three-way split made by Remco Zwetsloot and Allen Dafoe). I’ll discuss near-term problems people may be familiar with and then longer term problems.

In the near term, a paper called Concrete Problems in AI Safety looked at a cleaning robot and how it can move around a space and not lead to accidents. More generally, we find that our current machine learning systems go wrong a depressing amount of the time and in often quite surprising ways. While that might be okay at this stage, as they become increasingly powerful then the risk of accidents goes up. Consider the 2020 example of A Level grades being awarded by algorithms, which is an indication of how an AI system could really affect someone’s entire life chances. We need to be concerned about these accidents in the near term.

Misuse. We wrote a report a few years ago called the Malicious Use of AI (I think it was a good title so it got a fair amount of coverage). It looked at ways that AI could be misused by malicious actors, in particular criminals (think of cyber attacks using AI) and terrorists (think of the use of automated drone swarms) and how it could get misused by rogue states and authoritarian governments to surveil and to control their populations more.

Then there’s this idea of structure: structural risks or systemic risks. A few years ago, there was the so-called “flash crash”. The stock market had this really dramatic, sudden dip – then the circuit breakers kicked in and it came back to normal. But looking back on this, it turns out that it was to do with the interaction of many different automated trading bots. We still to this day are not entirely sure exactly what caused this flash crash

Paul Scharre proposed that we could have the same thing but a “flash war”. Imagine two automated or autonomous defense systems on the North Korea / South Korea border which interact in some complicated way, maybe at a speed that we can’t intervene on or understand. This could escalate to war. There’s not an accident and there’s not someone misusing it—it’s more the interaction and the structural risk.

Accident, misuse and structure also apply to the longterm.

The argument is that at this very transformative scale then all these safety problems become increasingly worrying. Human Compatible is written by Stuart Russell, who is the author of the leading textbook in AI (he just gave the Reith Lectures which are very good). He suggests that AI systems are likely to be given goals that they pursue in the world but that it might be quite hard to align these with human preferences and human values. We might therefore be concerned about very large accident risks.

The long-term misuse concern is the idea that these systems could get misused by all the people we talked about previously: criminals, terrorists and rogue states using AI to kill large numbers of people, to oppress or to lock in their own values. I put Superintelligence here by Nick Bostrom (but actually I think the definitive book has not yet been written on this).

The long-term structural concern is that the interaction of these powerful AI systems could lead to conflict (like with the flash war example) or simply competition between them that is wasteful of resources. Instead of achieving some measure of what we could achieve with humanity’s potential we could instead up end up wasting a large part of it by failing to coordinate, building up our defences, and racing for resources.

That’s the long-term risk of AI governance. To return to the slide that I tantalized you with at the beginning of the talk.

On the left we’ve got a bunch of paper clips, because one of the most famous thought experiments in AI safety and AI alignment is this idea of the paperclip maximiser. You are training this AI system to produce paper clips in a paper clip factory, and you have locked in this particular goal (of just producing more paperclips). You can imagine this AI system gaining in capabilities, power and generality and yet that might not change that goal itself. Indeed more generally, we can imagine very powerful, very capable systems with these strange goals. Because it’s just pursuing these goals that we’ve given it and we haven’t properly aligned it with our interests and values. If an AI system became more capable or acquired power and influence, it would have instrumental reasons to divert electricity or other resources to itself. This is the idea that is illustrated by the toy case of the paperclip maximizer.

Here in the middle, we’ve got some awful totalitarian despots from the mid 20th century, who ended up killing millions of their own people. If they had access to very capable AI systems then we might be very concerned about their oppressive rule being harder to end. AI systems could empower authoritarian regimes. A drone is never going to refuse to kill a civilian, for example. Improved and omnipresent facial recognition and surveillance could make it very hard for people to gather together and oppose such a regime.

Finally there’s some risk that any conflict that is caused by the interaction of AI systems could escalate up to nuclear war or some other really destructive war.

All three of these could be massive risks and could fundamentally damage our potential and lead human history to a sad and wasteful end. That’s the overall argument for how AI governance could go wrong.

Racing vs dominance

One spectrum that cuts across these three risk verticals is characterised by two different extremes that we want to avoid. One extreme is racing and one extreme is dominance. Racing has been talked quite a lot about by the AI governance community, but so far dominance hasn’t so much.

| Corporate | State | |

| Racing | Race to the bottom, conflict | |

| Dominance | Illegitimate, unsafe, misuse | |

Why could racing be a worry? We could have a race to the bottom: many different companies all competing to get to the market quicker. Or states in an arms race, like we had for nuclear weapons and for biological weapons. Racing to be the first and to beat their competition, they might take shortcuts on safety and not properly align these AI systems, or they could end up misusing them, or that racing could drive conflict.

Something that has been discussed less in game theory papers but I think we should also be concerned about is the idea of dominance by just one AI development and deployment project. If it was just one company, I think we can all agree that would be pretty illegitimate for them to be taking these huge decisions on behalf of the whole of humanity. I think it’s also illegitimate for those decisions to be taken by just by one state: consider if it was just China, just the EU or just the US. You can’t be taking those really monumental decisions on behalf of everyone.

There’s also the risk of it being unsafe. We’ve seen in recent years that some companies cannot really be trusted with the current level of AI systems that they’ve got, as it’s led to different kinds of harms. We see this often in history: big monopolists often do cut corners and are just trying to maximize their own profits. We’ve seen this with the robber barons of Standard Oil and US Steel and others in the early 1900s. We’ve seen it with the early modern European East India companies. Too much dominance can be unsafe. And if there’s just one group, then that raises the risk of misuse.

We really want to try and avoid these two extremes of uncontrolled races and uncontrolled dominance.

What is to be done?

So that’s all pretty depressing, but I’m not going to leave you on that – I’m going to say that there are actually useful things that we can be that we can do to avoid some of these awful scenarios that I’ve just painted for you.

| Corporate | State | |

| Racing | Collaboration & cooperation | Arms control |

| Dominance | Antitrust & regulation | International constraints |

Just to return to that previous race/dominance spectrum, there’s lots of useful things we can do. Take the corporate side. In terms of racing between companies, we can have collaboration and cooperation on shared research or shared joint ventures and sharing information. In terms of dominance: anti-trust and competition law can break up these companies or regulate them to make sure that they are doing proper safety testing and aren’t misusing their AI systems. That’s been a well-tried and successful technique for the last 100 years.

Take the state side. We’ve got an answer to these uncontrolled arms races: arms control. For the last 50 years, biological weapons have been outlawed and illegal under international law. There was also a breakneck, destabilising nuclear arms race between the USA and the USSR. But 50 years ago this year, they agreed to begin reducing their arsenals. On dominance: in the early 1950s when the US was the only country with nuclear weapons, many US domestic elites internally argued that this is just another weapon, we can use it like any other weapon and it should be used in the Korean War. But there was a lot of protest from civil society groups and from other countries, and in the end (from internal private discussions) we can see that those were influential and this non-use norm constrained people like President Eisenhower and his administration from using these weapons.

Let us consider some even more concrete solutions. First, two that can be done within AI companies.

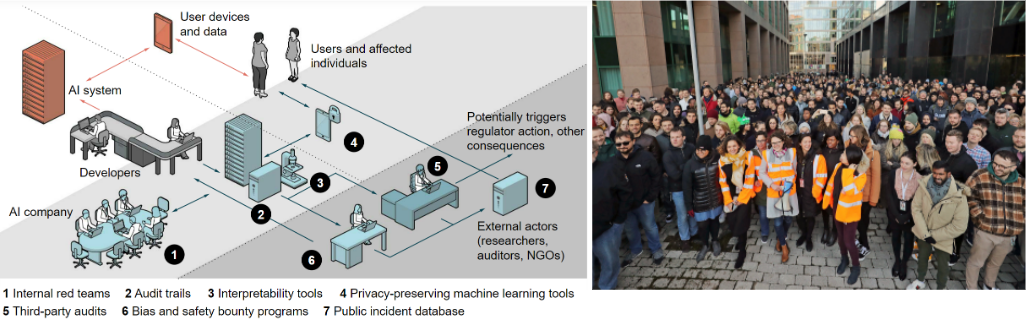

This is a paper we had out in Science in December 2021, which built on an even bigger report we did in 2020. It outlines 10 concrete ways that companies can cooperate and move towards more trustworthy AI development. Mechanisms like red teams on AI systems to see how they could go wrong or be vulnerable, more research on interpretability, more third party audits to make sure these AI systems are doing what they’re supposed to be doing, and a public incidents database

Another thing that can be done is AI community activism. This is a picture of the Google Walkout, discussed earlier. Google was doing other somewhat questionable things in 2018: they were partnering with the US government on Project Maven to create something that could be used for lethal autonomous weapons. Secretly they were also working on something called Project Dragonfly to create a censored search engine for the for Chinese Communist Party. Both of these were discovered internally and then there was a lot of protest. These employees were activist and asserted their power. Because AI talent is in such high demand, they were able to say “no let’s not do this, we don’t want to do this, we want a set of AI principles so we don’t have to be doing “ethics whack-a-mole””.

But I don’t think just purely voluntary stuff is going to work. These are three current regulatory processes across the US and EU and across civilian and military.

The EU AI Act will probably pass in November 2022. It lays out 8 different types of high-risk ai systems and it has many requirements that companies deploying these high-risk systems must pass. Companies must have a risk management system and must test their system and show that it’s, for example, accurate, cybersecure and not biased. This is going to encourage a lot more AI safety testing within these companies and hopefully a shared understanding of “our machine learning systems keep on going wrong, we should be more modest about what they can achieve”.

There’s a complimentary approach happening in the US with NIST (the National Institute for Standards and Technology), which is also working on what common standards for AI systems should be.

Avril Haines (who I talked about at the beginning of the talk) wrote this paper called Building Trust through Testing on TEVV (because US defense people love acronyms): testing, evaluation verification and validation. On the civilian side we want to make sure that these systems are safe and not harming people. I think we want to be even more sure they’re safe and not harming people if they’re used in a military or defense context. This report explores how can we actually do that.

Finally, there’s the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots. For the last eight years there’s been negotiations at the UN about banning lethal autonomous weapons—weapon systems that can autonomously select and engage (kill) a target. There’s been a big push to ban them. Even though we haven’t yet got a ban, people are still hopeful for the future. Nevertheless, over the last eight years there’s been a lot of useful awareness-building along the lines of “these systems do end up going wrong in a lot of different ways and we really do need to be careful about how we’re doing it”. Different people and states have also shared best practice, such as Australia sharing details of how to consider autonomy in weapons reviews for new weapons.

Across the civilian and military sides, in different parts of the world there’s a lot happening in AI governance. No matter where you’re from, where you’re a resident or citizen, where you see your career going or what your disciplinary background is, there’s useful progress to be made in all these different places and from all these different disciplinary backgrounds. There’s already been great research produced by people in all these different disciplines.

Let’s get even more concrete—what can you do right now? You can check out 80,000 Hours, a careers advice website and group. They’ve got lots of really great resources on their website and they offer career coaching.

Another great resource is run right here in Cambridge, the AGI safety fundamentals course also has a track on governance, I’m facilitating one of the groups. There are around 500 people participating in these discussion groups and you then you work on a final project. It’s a great way to get to grips with this topic and try it out for yourself. I would thoroughly recommend both of those two things.

To recap: I’ve talked a bit about my background and what the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk is. I’ve introduced this general topic of AI governance, then we’ve narrowed down into long-term AI governance and we’ve asked how could it go wrong at the scale of nuclear war, pandemics and climate change? The answer is accident risk, misuse risk and structural risk. But there are things that we can do! We can cooperate, we can regulate, we can do much more research, and we can work on this in companies, in academia in governments. This is a hugely interesting space and I would love more people to dip their toes in it!

Thanks for sharing your talk.

I’m at the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority. Very happy to talk to anyone about the intersection of competition policy and AI.

Good post! I’m curious if you have any thoughts on the potential conflicts or contradictions between the “AI ethics” community, which focuses on narrow AI and harms from current AI systems (members of this community include Gebru and Whittaker) and the AI governance community that has sprung out of the AI safety/alignment community (e.g GovAI)? In my view, these two groups are quite opposed in priorities and ways of thinking about AI (take a look at Timnit Gebru’s twitter feed for a very stark example) and trying to put them under one banner doesn’t really make sense. This contradiction seems to encourage some strange tactics (such as AI governance people proposing different regulations of narrow AI purely to slow down timelines rather than for any of the usual reasons given by the AI ethics community) which could lead to a significant backlash.

Hi, yes good question, and one that has been much discussed—here’s three papers on the topic. I’m personally of the view that there shouldn’t really be much conflict/contradictions—we’re all pushing for the safe, beneficial and responsible development and deployment of AI, and there’s lots of common ground.

Bridging near- and long-term concerns about AI

Bridging the Gap: the case for an Incompletely Theorized Agreement on AI policy

Reconciliation between Factions Focused on Near-Term and Long-Term Artificial Intelligence

Agreed. One book that made it really clear for me was The Alignment Problem by Brian Christian. I think that book does a really good job of showing how it’s all part of the same overarching problem area.

Thanks for taking the time to share this, Hayden. It was very useful.

To what extent do behavioural science and systems thinking/change matter for AI governance?

To give you my view: I think that nearly all outcomes that EA cares about are mediated by individual and group behaviours and decisions: Who thinks what and does what (e.g., WRT. careers, donations, and advocacy) etc. All of this occurs in a broader context of social norms and laws etc.

Based on all this, I think that it is important to understand what people think and do, why they think and do what they do, and how to change that. Also, to understand how various contextual factors such as social norms and laws affect what people think and do and can be changed.

I notice related work on areas such as climate change, and I project that similar will be needed in AI governance. However, I don’t know the extent to which people working on AI governance share that view or what work, if anything, that has been done. I’d be interested to hear any thoughts that you have time to share.

Also, I’d really appreciate if you can suggest any good literature or people to engage with.

I’m not Hayden but I think behavioural science is useful area for thinking about AI governance, in particular about the design of human-computer interfaces. One example with current widely deployed AI systems is recommender engines (this is not a HCI eg). I’m trying to understand the tendencies of recommenders towards biases like concentration, or contamination problems, and how they impact user behaviour and choice. Additionally, how what they optimise for does/does not capture their values, whether that’s because of a misalignment of values between the user and the company or because it’s just really hard to learn human preferences because they’re complex. In doing this, it’s really tricky to actually distinguish in the wild between the choice architecture (behavioural parts) vs the algorithm when it comes to attributing to users’ actions.

Hi both,

Yes behavioural science isn’t a topic I’m super familiar with, but it seems very important!

I think most of the focus so far has been on shifting norms/behaviour at top AI labs, for example nudging Publication and Release Norms for Responsible AI.

Recommender systems are a great example of a broader concern. Another is lethal autonomous weapons, where a big focus is “meaningful human control”. Automation bias is an issue even up to the nuclear level—the concern is that people will more blindly trust ML systems, and won’t disbelieve them as people did in several Cold War close calls (eg Petrov not believing his computer warning of an attack). See Autonomy and machine learning at the interface of nuclear weapons, computers and people.

Jess Whittlestone’s PhD was in Behavioural Science, now she’s Head of AI Policy at the Centre for Long-Term Resilience.