Mushroom Thoughts on Existential Risk. No Magic.

written by Carla Zoe Cremer, illustrated by Magdalena Adomeit

Merlin Sheldrake’s book Entangled Life, has much to teach us about existential resilience, conservation and the climate crisis. The world of fungi guards the secrets of longterm survival. But the principles which underlie their resilience extends much beyond the kingdom of fungi into lessons about the persistence of life.

In Sum

The ubiquity of symbiosis questions whether the prevention of our extinction can be accomplished by saving the human species alone. Avoiding extinction and existential risk appears inextricably entangled with the survival of a sizable number of other species, many of which we have yet to identify.

Fungi stretches the category ‘technology’ in my mind. Sheldrake lists a surprisingly large range of mycelium-based applications which play a role bio-sensing, factory-farming or construction. Their metabolic functions are promising technology. We should study what we already have and use it well.

At last, fungi exemplify a trade-off between yield and resilience, which questions whether the apparent arch of progress we associate with modern industry and agriculture is real – particularly from a longtermist perspective.

I present some initial thoughts on the relationship between fungi and existential risk. This is not my speciality. I chose to describe my naïve impressions frankly, but I intend to keep an openness to changing mind. My aim is not to present water-tight arguments, but instead provide a taste of a perspective. Try to indulge in the fuzziness.

I collected some facts about fungi from Sheldrake’s book, but I encourage you to read the book in full. It contains extensive references to primary literature in endnotes. If you are familiar with what fungi are and what they can do for us, feel free to skip to the last section, in which I relate those facts to existential risk.

Fungi are eukaryotes. Their biomolecular structure is closer to animals than plants. They are ubiquitous. You will find fungi in most places on the planet, including yourself. Constructed of hyphae – elongated tubes which form mycelium networks – they lack a central nervous system. And yet, they are mysteriously able to make sophisticated decisions across tough trade-offs, directions and survival strategies. In exploration of their territory, the tips of mycelia will grow outwards in a spherical from. One of many tips, upon having discovered a desirable destination, will redirect growth of the whole networks using electric pulses (possibly analogous to action potentials in brains). How exactly decisions are made, and coordination is achieved, we do not yet know.

90% of fungi species have not yet been classified. Estimates on the existing number of species range from 2.2-3.8 Million, which could be 10 times more than the number of plant species.

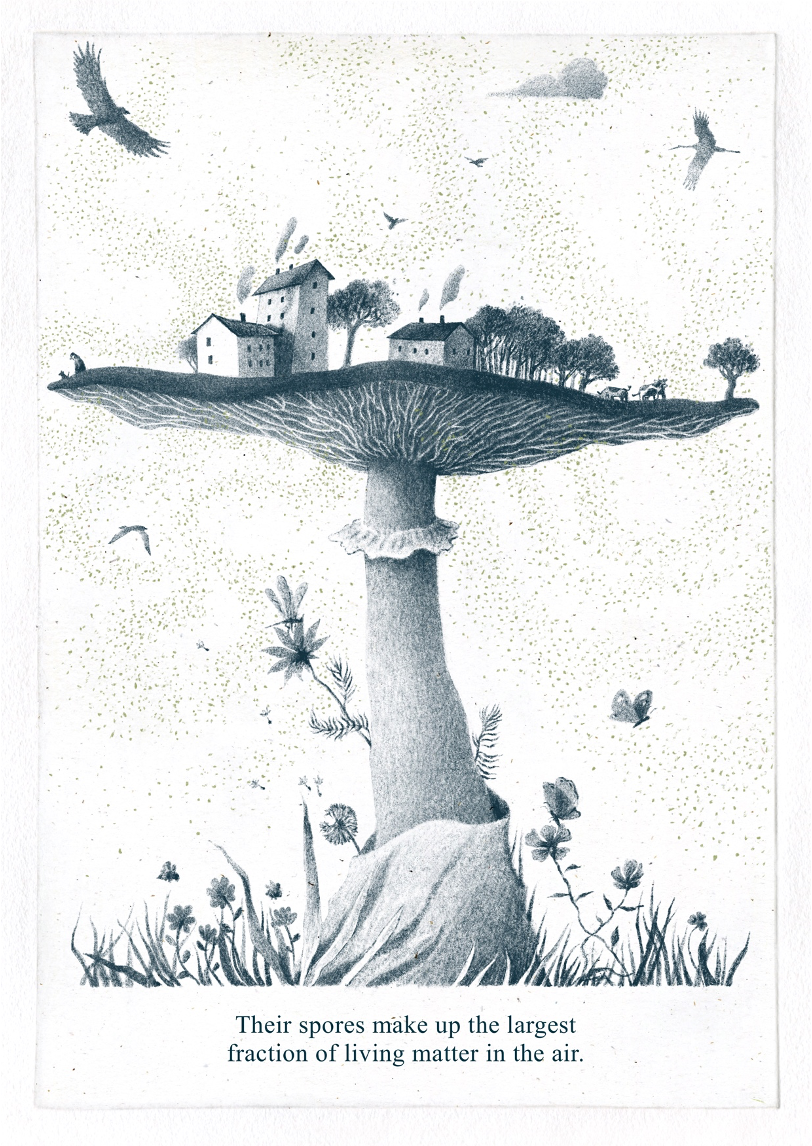

Fungi appear to be able to digest nearly everything (raw oils, TNT, stone, radioactive material…). If they can’t directly digest one material, you can teach them. Some release their spores explosively, reaching a speed of 100 km/h, making them one of the fastest organisms on the plant. Their spores make up the largest fraction of living matter in the air (50 Million tonnes per year). These spore loads affect the weather.

If you’d measure mycorrhiza hyphae in the first 10 centimetres below ground, they would cover the length of half of our galaxy (4.5 x10^17 kilometres). The largest living organism on this planet is a fungus (Armillaria in Oregon) – this specimen is 8000 years old.

For millions of years, fungi were the only large organisms. These prototaxites were meters-high, pillar-like ecosystems. Ca. 400 million years ago, plants were enabled to move onto land and grow into trees, due to mycorrhiza (fungi-roots), which granted them better access to vital phosphor.

According to computational models, the symbiotic efficiency between plants and fungi alone, can result in changes to the earth’s climate. CO2 and oxygen levels in the atmosphere were dependent on the efficiency of the trade between plants and fungi, leading to changes in global temperature (e.g. 300 Million years ago). Humans, who live in a specific temperature range, are reliant on such regulation.

We’re only beginning to understand the role of fungi in forests. The speed of forest movement depends in parts on the efficiency of their relationship to mycorrhiza. Fungi drive evolutionary variety and allow organic growth in areas that would otherwise be too hostile. The ecosystem services we derive from forests, depend vitally on the health of fungi-infused soil. Today, more than 90% of plants rely on mycorrhiza for their nutrients and information flows. Some plants cannot survive without them, which questions the very idea of separable species. In essence, fungi build trading networks for organisms in the forest, providing fertile ground for studying inequality, cooperation or defection in natural markets.

Impressive Applications of Fungi

Medication: The genus homo has long been using fungi for medicinal purposes. Most recently, humans started using penicillin, cyclosporin (used for organ transplants) and psilocybin. How many medications remain undiscovered, considering how many fungi species are still unknown?

Problem solving: A number of studies examine how fungi are able to find the most efficient path through a complex environment of obstacles. They will for example, naturally replicate the road network in Tokyo or ancient Rome.

Resilience and Space-travel: Fungi have survived all five mass extinction events. Lichen – roughly a symbiotic union between fungi and algae – are being tested as a promising candidate for surviving space conditions. Astrobiologists found them to be resistant against 6 kilograys of radiation (12.000x as much as the lethal dose for humans). At 12 kilogray, they still do photosynthesis. Dip them in liquid nitrogen of −195 degrees Celsius—nothing happens. They are found in adverse earth-bound conditions such as deserts, volcanic springs, or underneath tonnes of ice sheets, as well as kilometres deep underneath the earth’s surface in the midst of immense heat and pressure. Some of them are thousands of years old. I’d be surprised if we cannot learn a thing or two about resilience from fungi.

Both lichen and humans are an excellent example of the incredible resilience and extraordinary intelligence that can emerge from symbiotic unions.

Lichen are a mini ecosystem – a process of symbiotic, dynamic interaction between organisms who each contribute functions that the others are lacking. The survival of each depends so vitally on others, that they blur the boundaries of the concept species. While each of course is identified by their unique DNA, the ability to stay alive is ensured only through the existence of a symbiotic partner: a full set of foreign DNA.

The term holobiont tries to capture this: a cooperative assembly of separate genetic entities that form an otherwise impossible organism. Humans of course are holobionts or as Sheldrake calls us: symborgs. Both lichen and humans are an excellent example of the incredible resilience and extraordinary intelligence that can emerge from symbiotic unions.

Conservation and ecosystem services: Fungi can drastically reduce the rate of bee death. They can absorb toxins in soil or water. Mycelium sheaths will filter water from heavy metals.

They can digest toxic waste or other materials that we have no use for (which means we don’t have to burn it and pollute the air), including cigarette buds (of which we accumulate 750.000 tonnes per year), diapers (ca 15% of waste in cities), nerve gas, pesticides, TNT, synthetic colours, plastics, synthetic hormones and antibiotics, oil spills, and radioactive materials (so-called ‘radiotrophs’ thrive off radioactivity). More interestingly, if the conditions are right, fungi can learn and re-activate dormant genes, to digest materials which they usually do not digest.

The company CoRenewal uses fungi to eliminate toxins associated with oil extraction. In California, we fight the toxic sewage resulting from wild-fires in 2017 with mycelia-pipes.

Biofabrication: Fungi can be used to construct building materials, fabrics or leather. The company Ecovative has a mycelium factory for ecological packaging, furniture and bricks. NASA wants to use it to build and furnish houses on the moon and DARPA want to make self-repairing fungi-buildings. The research project FUNGAR has even more ambitious plans.

Though human extinction surely is the loss of our DNA, we will need to think beyond our gene code to prevent it.

Bio-sensing: Certain fungi such as phycomyces are highly sensitive to environmental conditions (toxins, temperature, humidity…) and could serve as a sensor to signal maladaptive changes or detrimental waste products in the environment.

Mycelium-computing: Electrical communication in mycelium networks can be used to build circuits. Prototypes, mostly for bio-sensing, are in development.

Medicinal Psychedelics: LDS and psilocybin are derived from fungi and have a long tradition of being digested by humans. They are now being investigated for their therapeutic effects on mental illness.

Fungi and Existential Risk

Surviving Alone

Human survival and flourishing never relied on human DNA alone. Though human extinction surely is the loss of our DNA, we will need to think beyond our gene code to prevent it. The number of microbes we carry (ca. 40 trillion) plausibly exceeds the number of our human cells. Our ecosystem of microbes is integral to our minds, immune function, cell function and growth. There are an unfathomable number of individuals that make us the individual we think we are. Bacteria can further host viruses, and they too affect the function of bacteria in our body.

As I considered how exactly our life form survives – which is as a holobiont and symborg – I became increasingly unsure about what other species we may need to save, if we wanted to save ourselves. Without which organisms would our survival chances plummet? We’d be wise to protect constituents of our life form whose function we do not yet understand. These functions may be more vital to us than we now recognise.

Life indispensably relies on symbiosis. Certain plants, such as Voyria, have ceased to perform photosynthesis: they cannot survive without fungi that deliver essential nutrients. Evolution does not “repair” the insufficient functionality of each organism – instead, organisms find symbiotic partners who fill their metabolic gaps. Life is distributed across species, not detained by each one of them.

The anthropologists Myers and Hustak use the term involution to describe this approach to overcoming biological limitations. Organisms drive (to survive) into the life, territory and metabolism of other, existing organisms, rather than to compete or identify niches which are not yet occupied.

Our knowledge of how exactly new shapes emerge and persist is still humiliatingly incomplete. Sheldrake calls it dark life.

Symbiosis is not nice. It is not altruistic, feminine or naïve. Organic fusions pursue an amoral strategy. Materialism underpins each union. Evolution is the game structure and symbiosis does not preclude competition to exist alongside it. But biology simply does not play a zero-sum game. It is rarely the rational choice to fend for yourself as a species on this planet.

It was a symbiotic relationship between algae and fungi that allowed plants to move on land. This transition enabled everything we now value. Symbiosis prompts the emergence of new life forms. Our knowledge of how exactly new shapes emerge and persist is still humiliatingly incomplete. Sheldrake calls it dark life.

Over the long run, humans could witness how new, unimaginable and precious life forms emerge. Symbiosis will play a role. It seems short-sightedly unwise to gamble with the extinction of current species, species which could be the foundation of a radically better and more spacious future life.

Anti-Fragility

Mycelium is one of the oldest (2.4 bn yrs) multicellular life forms ever found. Clearly fungi are rather robust. Fungi are adaptable and flexible in form and nutrient requirements. A significant fraction of their resilience can be attributed to their promiscuity in building symbiotic relationship with other organisms. The least we can do is to check whether we can learn lessons about anti-fragility from fungi and see whether they may be applicable to our own species. It would be strategically ill-informed to leave the research on fungal functions untouched and under-funded.

Permanence is fragile.

Sheldrake thinks of long-lived life forms as processes, rather than static entities. Therein lies a crucial lesson: the difference between security and anti-fragility. Permanence is fragile. We cannot afford to desire stability, to fulfil our need to control and secure. Trying to stay the same, in a dynamic, conjunctional environment is wasteful and risky. We should instead balance our form and strengthen our resilience. Humanity too is a process. We should learn to adapt to and absorb shocks.

Collecting Technology

I encounter much optimism about global biodiversity loss. Bioengineering, the optimist argues, will let us revive (de-extinct) species, if we retrospectively deem them useful. I wish I was convinced. But instead, this appears overconfident and rushed.

I have my doubts about the sophistication of our bioengineering abilities. Sheldrake describes how the truffle industry has all but failed to technologically control the yield of truffle. Incentives are not amiss: the truffle industry is ripe with murders and robberies due to the amount of money that can be made with say, a well-trained truffle dog. But the interactions between organisms and the environmental conditions in the soil are (for now) too complex to replicate in laboratory conditions. The object of desire, and in this case its aroma, is inextricable dependent on the chemical and atmospheric conditions in which the truffle grows. The species of interest is not separable from its home ecosystem.

Apart from my scepticism that we can replicate and revive whole ecosystems and their species in the near future, it strikes me irrational at best to neglect a perfectly well-functioning machinery to the point of decay, only to build a new one from scratch.

Where is the efficiency in that?

Fungi could reduce pollution, atomic waste, bio-diversity loss, toxins, mental illness… they could contribute to resilient agriculture, space travel, bio-engineered materials…the list goes on and is yet incomplete. ‘Dark Life’ is ripe with fruitful tech: picking it is a matter of choice and funding.

Imagine if little pieces of artificial intelligence were lying around on the ground. A little concept formation here, a little continual learning and causal cognition there…why would we not pick it up? We may not need AI as urgently as we think. Fungal metabolic functions can already solve a number of our problems. Our conception of technology is inconsistent. We describe the human brain as complex computer and our bodies as sophisticated machines. The logical conclusion is that non-human life forms too are little machines. We should protect their functionality with the same eagerness as we are aggressively pursuing artificial intelligence to be built and solve all our problems.

Indeed, fungal applications, will in most cases likely integrate more safely with our civilisation than an artificial machinery we build from scratch. Many good solutions will not need to be engineered in full– just like one does not need to assemble (or understand for that matter) a computer in order to write great software. As we understand how to apply metabolic functions of existing species to our needs, we enter into a symbiotic relationship. They become technology.

‘Dark Life’ is ripe with fruitful tech: picking it is a matter of choice and funding.

Origins of Existential Risk

The industrial revolution and its effect on crop yield are generally praised. But the timescales we look at are rather short. Improvements in yield may not ensure food supply longterm.

Modern agriculture has a large carbon footprint and chemical fertilisers are destroying the health of our soils (at the rate of a fertile area of 30 soccer fields/minute). Despite a 700-fold increase in the use of pesticides during the second half of the 20th century, yield remains constant but 20-40% of domesticated plants are still lost to pathogens.

A deterioration of soil health is followed by a disruption of symbiotic exchanges between fungi and plants. Fungi no longer fuel the immune system of plants. Crop resilience against pathogens, temperature extremes, heavy metals and salt decreases. As much as they help, fungi don’t generate the kind of artificial yield we have become used to: we observe a trade-off between resilience and maximal yield.

From a perspective of a longtermist, this case study is an emblematic story of how we often choose to increase yield in the short-term, in exchange for long-term benefits. And whilst our climate seems stable, modern agriculture may look like a technological success story in support of Steven Pinker. But we know the climate is about to be anything but stable. We may have traded a rich-looking exploit, for anti-fragility. This was probably an unwise trade. From the perspective of longtermism, it may simply have been stupid.

Such case studies might lead us to re-examine the origins of anthropogenic risk to our longterm flourishing. Longtermists must think more thoroughly longterm. We must consider whether what looks like an arch of progress over decades, could turn out to have been a mere depletion of resilience and thus a shift of the risk-distribution. Improvements in quantity of anything must come from somewhere, and we better make sure they don’t derive from the buffers we need in tougher times.

In Conclusion

Fungi are impressive, significantly under-explored and could be the solution to many issues. Thinking about them brings joy and challenges notions of resilience, species extinction and preservation. We should consider investing into more neglected research in this area.

Do you have one or two sources you’d recommend that make a strong case that crop yields will plausibly decline on any particular timescale? Particularly if those sources also incorporate factors like potential gains from genetic engineering, potential inefficiencies from increased meat production, etc.?

I see many references to soil health as an ongoing crisis, but I haven’t seen any forecasts about actual outcomes / tipping points that stick in my memory. Our World in Data finds gradually increasing yields since mid-century; the trends seem to have flattened a bit recently, but it’s hard to tell how much of that is the end of easy gains from Green Revolution vs. active negative trends beginning to take effect.

The EA longtermist community is tiny, and it’s easy to imagine even very strong evidence of long-term food supply risk being missed. But even ALLFED, which has a deep focus on related topics, seems to focus almost entirely on risk of crop loss from major disasters rather than ongoing climate change. I’d be interested to know about ALLFED work I’ve missed, or other good resources that people at places like Open Phil should think about.

Regarding sources that argue about risks on crop yields in the future, I have collected some over time. Apologies for not explaining them more thoroughly—they include reports of past/current crop losses as well as predictable ones, of course caused by many different factors:

Future warming increases probability of globally synchronized maize production shocks (2018)

Amplified Rossby waves enhance risk of concurrent heatwaves in major breadbasket regions (2019)

Climate Change Impacts on Global Food Security (2013)

Plant pathogen infection risk tracks global crop yields under climate change (2021)

World agriculture towards 2030/2050: the 2012 revision (2012, UN FAO)

The global groundwater crisis (2014)

Anthropogenic depletion of Iran’s aquifers (2021)

Oxfam Media Briefing 27.4.2017 https://www.oxfam.de/system/files/mb-climate-crisis-east-africa-drought-270417-en.pdf (To the trend in (mostly rain-fed) African agriculture)

Increased future occurrences of the exceptional 2018–2019 Central European drought under global warming (2020)

But this is all a bit here and there, not an expert who can evaluate the validity of this research

Thanks for the links! I appreciate your taking the time to share them, and they all seem relevant to my question.

Hi Aaron, I’m afraid as mentioned I don’t know this area very well so I’m not familar with the literature and cannot point you towards particular papers. I used this fungi case study as an example to point out that risk must be understood as more than the hazard (e.g. drought), but also the vulnerablity (e.g. resilience levels of plants against drought): if resilience has decreased, the trend in yield will not decrease to show the increased risk up until the point where the hazard hits and the vulnerability is exploited.

But I’m happy to point Open Phil towards researchers who do know and think a lot more about this. Tail-risk studies in climate change are generally neglected, so some of our peparedness efforts might have to be based on conversations with experts rather than a literature search.

If there are particular researchers you have in mind, I’d guess that ALLFED would be very interested in talking to them (if they haven’t already). I’d like to share this comment thread with the folks I know there. What are the names you were thinking of?

Carla-nice piece! I direct the Alliance to Feed the Earth in Disasters (ALLFED). We are indeed concerned about tail risks from climate change. We have also considered two different resilient foods for global agricultural shocks related to fungi: mushrooms and fungus grown in bioreactors. Mushrooms have the advantage of the potential to scale extremely rapidly and grow on fiber (e.g. agricultural residues or wood), but they are expensive. Quorn is a fungus that is currently grown on grain, so in a catastrophe, eating the grain would generally make more sense (though Quorn would be better than feeding animals). However, it would be possible to have fungus in a bioreactor grow on fiber, which would be resilient. But unfortunately, neither of these bioreactor options is very economical at this point.

That sounds cool. Happy to see that some of this work is going on and glad to hear that you’re specifically thinking about tail-risk climate change too. Looking at fungi as a food source is obviously only one of the dimensions of use I describe as relevant here, and in ALLFED’s case, cost of the production is surely only one relevant dimension from a longtermist perspective. In general, I’m happy to see that some of your interventions do seem to consider fixing existing vulnerabilities as much as treating the sympoms of a catastrophe. I’ll go through the report you have online (2019 is the most recent one?) to check who you’re already in contact with and whether I can recommend any other experts to you who it might be useful for you to reach out to.

On a seperate note and because it’s not on the Q&A of your website: are you indeed fully funded by EA orgs (BERI, EA Lottery as per report)? I found it surprising that given your admirable attempts to connect with the relevant ecosystem of organisations you would not have funding from other sources. Is this because you didn’t try or because it seems no one except EAs want to grant money for the work you’re trying to do?

I found this post interesting, thank you.

I think it’s of a very different style than most post on the forum. Those illustrations are far more intricate and artistic than anything I’ve seen here (nice work!). It reminds me a lot of pieces I’d see in more literary journals.

Looking at the current vote count, it seems like people were fairly conflicted on this particular piece. I could definitely intuit some of why; mainly because it’s so unusual. Most EA forum posts are very much to-the-point and factual, this one seems more exploratory. I’m a bit conflicted here because I could sympathize with both sides. At the same time, it’s really not fun to spend so much work on a piece and get what seems to be no engagement. (though, in fairness, I think that because this work is so speculative, and because there hasn’t been much discussion of the topic here, it is difficult to engage with)

I think that Fungi could probably use a fair amount more investigation by many sectors. They seem very promising, but also so far seemed like a huge challenge to understand and work with. There are several really neat tech companies and academics still experimenting with them.

I’m fairly conflicted on a lot of the x-risk applications discussed in this point, but would agree with a few main points:

Fungi are just really interesting, and they might have applications to fields we care about. (Definitely climate change, maybe bio risk somehow?)

Destroying the climate, including all fungi, would be an incredibly bold and likely massively destructive endeavor anytime soon (at least until we become massively more intelligent and wise)

Resilient studies could be valuable. I’m not sure how many lessons we can take from fungi, but maybe there are some.

Thanks Ozzie! Yes, I’m very aware that this is a strange post for the EA forum. In fact I think this post would have been strange anywhere. There’s no venue and a small audience for a post on fungi and existential risk.

Yet as with platforms such as instagram or twitter, I’m a fan to try defy the accepted and most rewarded formats and move the needle a little towards a more flexible format and more flexible thinking. That does of course mean that I give up likes or upvotes, but I have not spend enough time on these forums to care about this. Unfortunately I think there is a considerable number of posts that get upvoted a lot more than I would have found appropriate given their level of scholarship or originality. Lastly, the post did not take much time to write—as I mention I simply wrote up my naive impressions, in parts because I wanted to retain memory of the content of the book, in parts because there’s not much disccusion within EA on ecology-existential risk. I don’t know how long the illustrations took, but Magdalena is very talented and I suspect not much. So, thank you for you sympathy, but I’m ok :)

As for the rest of your comment: feeling conflicted seems useful! I agree with your last bullet points, even though they are so broad they are hard to argue with I guess (destroying the climate?). I have very little hope that this article alone will inspire grant funders to consider fungi research or start-ups, nor that EAs suddenly become very interested in ecology research, species extinction and the lessons we can learn from the climate crisis about existential risk.

But if I make it more likely that others who (unlike me) have studied these subjects, will write about them here and feel justified in steel-manning the position that our earthsystems and ecosystems play a vital role in existential risk, then I have moved the needle a little.

This is an incredibly beautiful piece and I think the EA forum would benefit from many more like it in style.

I live in a place and spend time with people who are very aligned with you (close to the birthplace of the modern environmental movement, direct action, etc.).

Here’s a picture from a retreat where we got up to meditate in the cold morning and do a lot of other activities like replant/move mycelium.

However I am concerned about ideas and content in this piece:

and

I think the thinking behind this might touch on issues I am worried about:

AI and Longtermism (in the specific sense of accounting for future populations with low or zero discounting) are precious cause areas/worldviews.

However, it seems that the current, apparently intense interest in it, involves messaging issues/rhetoric that can create structural problems.

(To be more specific, communication/cultural issues will create noise that disrupts activity and involvement even among informed and involved people, e.g., everyone, including informed EAs, jockeys to tag their cause with “Longtermism” and this has consequent effects on discussion and Truth).

Maybe communicating various topics better would help. Here are some candidates:

A description of prosaic AI that emphasizes it is pretty much scaled up pattern matching (see GPT series), and providing information on what non-prosaic is and is not.

Presentations of Longtermism that don’t include rhetoric or results that lend itself to overly broad interpretations, especially if the concept isn’t that hard to understand or new.

More communication about gritty operational and implementation details in projects related to Longtermism

The obvious benefit is to make the cause more accessible but there are other benefits:

“Customer service” is a critical form of leadership in many communities and underappreciated and I think the above makes this activity more feasible and productive. It will also reduce the “distance” between public discussions and actual gears-level work (e.g. MIRI papers). It will also help “taste the soup” of actual operational and implementation details of Longtermist projects.

Hi Charles, I’m afraid I didn’t really understand your comment. These are pretty pictures though!

Great piece, well done!

Thanks Kevin!

Hi Zoe, I was coincidentally browsing the ea forum this evening (I only do on odd occasion) and saw your name on this and decided to take a read—not least of all because I was interested in the piece but I had also seen Sheldrake’s name on there and thought it was funny how these two worlds of mine had seemingly collided (Merlin is an old friend). Anyway, I thoroughly enjoyed this and the speculative nature of the piece, so I just wanted to pass by and say so. Hope you and the rest of the RSP gang are well and things are going as well as ever. Best, Alex

Hi Alex—thanks for stopping by of course! Delighted you found it enjoyable to read. How cool that you know Merlin, he seems fascinating. We’ve only briefly been in contact and I can’t wait to see what he does next after this book was such a success. He seems to be a deeply creative person.

For anyone who doesn’t know Merlin and wants to get a taste: here’s a video of him eating his own words :)