Thank You For Your Time: Understanding the Experiences of Job Seekers in Effective Altruism

Summary

The purpose of this research is to understand the experiences of job seekers who are looking for high-impact roles, particularly roles at organizations aligned with the Effective Altruism movement (hereafter referred to as ”EA job seekers” and “EA organizations,” respectively).[1]

Organizations such as 80,000 Hours, Successif, High Impact Professionals, and others already provide services to support professionals in planning for and transitioning into high-impact careers. However, it’s less clear how successful job seekers are at landing roles that qualify as high impact. Anecdotally, prior EA Forum posts suggest that roles at EA organizations are very competitive, even for well-qualified individuals, with an estimated range of ~47-124 individuals rejected for every open role.

Given that some EA thought leaders (Ben West, for example) have suggested working in high-impact roles as a pathway to increasing one’s individual lifetime impact (in addition to “earning to give”), it seems important to understand how well this strategy is working. By surveying and speaking with job seekers who identify as effective altruists directly, I have identified common barriers and possible solutions that might be picked up by job seekers, support organizations (such as those listed above), and EA organizations.

The tl;dr summary of findings:

A majority of EA job seekers are recent graduates or early career professionals with <10 years of experience.

Self-reported perceptions about their job search are overwhelmingly negative, with 89% of survey respondents citing negative feelings such as stress, frustration, and hopelessness.

In 1:1 interviews, subjects cited problems with employer hiring practices (lack of transparency, inconsistent definitions, and lack of feedback provided) as well as perceptions that EA organizations are seeking elite, Western talent. Lack of elite credentials, the “right” connections, and both economic and geographic barriers were cited.

Possible solutions include more networking and pursuit of alternatives (for job seekers), more practical guidance (provided by support organizations), and improving transparency and feedback (for employers).

None of these recommendations, however, will address the core problem of demand for “high impact” jobs outstripping supply. Job seekers may find it helpful to consider a wide variety of opportunities across the nonprofit, government, and private sectors. Creating a broad definition of what “impactful” work means (and/or which organizations are considered “effective”) may also reveal more options.

Research Questions

Where are EA job seekers in their career journey?

How do EA job seekers feel about their current search?

What barriers do EA job seekers face?

What resources, beyond what’s currently offered, might help EA job seekers prepare for and obtain high-impact roles?

Existing Evidence

The EA community has already done quite well in provisioning individuals with resources and services to support their transitions into a high impact career field. The most well-known resource is 80,000 Hours, which provides a job board, career guide, and very limited 1:1 coaching. Successif provides customized services aimed at mid-career professionals including coaching, mentoring, training, and matching. High-Impact Professionals provides a directory and “impact accelerator” workshop for professionals who want to identify different pathways to impact. All three organizations appear to be grant-funded and apparently offer their services for free. All appear to have a competitive application process and limited capacity to meet demand from job seekers. There are other organizations with similar missions, but these three seem to be the most well known.

As for the experiences of EA job seekers, we have mostly anecdotes. I reviewed relevant EA Forum posts and summarize main themes below (with links to a few posts that are illustrative):

Roles at EA organizations are highly competitive. Job seekers perceive that organizations are looking for elite talent with outstanding credentials.

Existing connections seem to increase one’s chances of landing a role.

Applying for EA roles is reported to be more costly than applying for non-EA roles due to time-consuming work tests and trials. Even if paid, there is an opportunity cost for working professionals who have difficulty finding time for these activities.

I did not find enough information about EA job seekers themselves or where they were in their career journey to make meaningful generalizations. Many posted anonymously or provided limited information about their backgrounds to avoid reputational risk.

Methods

The research was conducted in two parts: a brief online survey, and 15-min semi-structured interviews with respondents who opted-in to be contacted. The survey was distributed in two EA Slack channels (EA DC and EA Anywhere), the Successif Discord server, and the 80,000 Hours LinkedIn group, and was open from August through September 2023. A total of 91 responses were received, and of those, 59 respondents (65%) opted-in to be contacted for an interview.

Interviews were conducted on a rolling basis until theoretical saturation was reached. The interview format included a set of standard, open-ended questions: why each respondent felt as they did about their current search, what strategies they’ve tried that worked well (or did not work well), and what resources would be most helpful to them. A total of 19 video or phone interviews were conducted. Interviews were not recorded; only manual notes were taken.

Because of the exploratory nature of the research and lack of prior assumptions about EA job-seekers’ personal experiences, a grounded theory method of analysis[2] was used. Responses were broken down into discrete data chunks and open coded. Next, the codes were grouped into broader categories. Lastly, selective coding was used to identify common themes.

Survey Results

Career stage

Nearly half (47.3%) of respondents were early-career professionals with less than 10 years of work experience (Figure 1). The second largest group were mid-career professionals (26.4%), followed by recent graduates (16.5%), students (6.6%) and senior professionals with 20+ years work experience (3.3%).

Feelings about job search

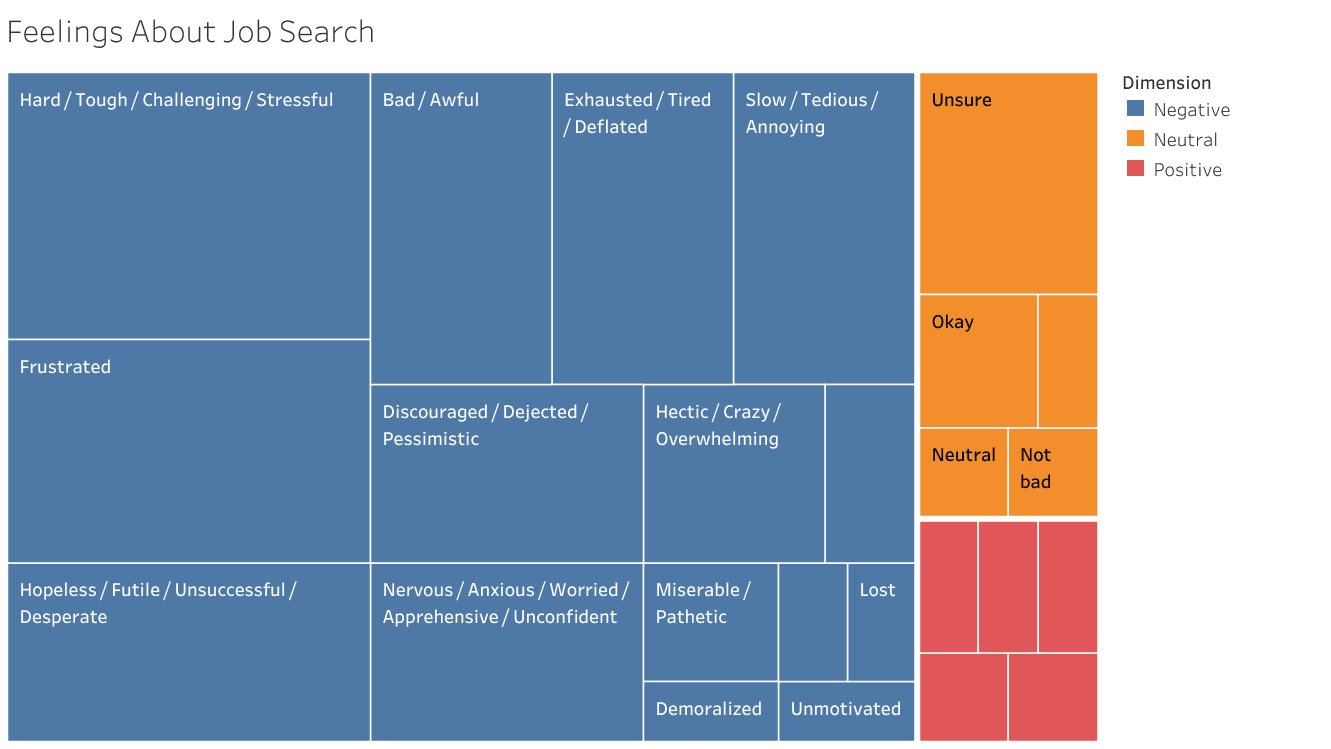

When asked how they felt about their job search, 92% provided a response (N=84). The responses were overwhelmingly negative in tone. Some responses included both positive and negative feelings and were coded for both (this is why the number of responses below add up to 90). A total of 75 (89%) of respondents shared negative feelings, 10 (12%) shared neutral feelings and 5 (6%) shared positive feelings. The content analysis below (Figure 2) shows the frequency of each feeling word used, grouped by synonyms wherever possible. Overall, looking for a job is hard on one’s emotional well being, both in EA and, I suspect, outside of it as well.

Barriers to finding the right job

There were clear themes among responses to the question of what barriers were preventing job seekers from finding the right job, which align with those cited in existing literature on the EA Forum. These themes were:

Barriers arising from one’s own background or skills, which included: needing to switch fields (also expressed as being in the “wrong” field), with 19 mentions; personal psychological issues such as low confidence or imposter syndrome (15 mentions); age[3] (11 mentions), and lack of a professional network (7 mentions).

Barriers presented by employers and the overall job market, which included: competition for roles (13 mentions), difficulty finding roles that would be a good fit (11 mentions), immigration issues or perceived discrimination against people from one’s country/region (11 mentions), perceived unreasonable expectations from employers during the hiring process (10 mentions), and lack of transparency around what employers are actually looking for (8 mentions).

Barriers of personal circumstance, which included: inadequate time to spend on the job-seeking process (5 mentions), and salary requirements (4 mentions).

Helpful resources and supports

The most helpful resources cited by survey respondents were the 80,000 Hours website and job board (23 mentions), professional networks and connections (20 mentions), and LinkedIn (16 mentions). The top three supports that would be helpful to job seekers, if made available, were strategies for better networking and connection building (60 responses), help preparing for interviews (50 responses), and adaptive courses to strengthen knowledge or skills (45 responses). Additional results are included in the Appendix.

The survey also asked about broad skill areas in which respondents would like to attain expert-level knowledge. The objective of this question was to understand where individuals might invest their time in learning something new, rather than their perceptions about which skills were marketable or useful to the job search. Because responses were nearly evenly distributed with a high number of “Other” responses, the results were inconclusive and are included in the Appendix.

Interview Results

The 1:1 interviews provided important context for the survey results, helping to explain why job seekers felt as they did. The 19 interviewees were located across four continents (Africa, Europe, North America, South America, and Oceania)[4]. Their career interests included AI safety and governance, animal welfare, climate change, democracy preservation, and global health and development. The amount of time interview subjects had spent searching ranged from as little as a month to as long as three years, but the average was 4 months.

In analyzing interview notes, I identified 11 initial categories which were divided among 5 major themes that encompassed the barriers job seekers face, and solutions (proposed by job seekers themselves) that might address these barriers.

Barrier 1: Employer Hiring Practices

Lack of transparency

The majority of interviewees mentioned a lack of transparency in the hiring process. Several used the words “black box,” despite the organization clearly laying out steps in advance. My interpretation of this finding is that there are actually two tiers of process for every search: the one that is explicit (i.e., clearly laid out steps on the organization’s website from interest form to work trial), and the one that is implicit (i.e., how decisions are actually made about who to hire). It is this implicit process that, I believe, most interviewees were referring to and caused them the most frustration. One interviewee put it this way:

“Yes, the application process seems transparent but there’s an invisible black box around it, something nebulous happening behind the scenes.”

The desire for more transparency applied not only to the hiring process, but also to the organization itself. For example, several interviewees spoke of not being sure the jobs (or organizations) were real. The practice of re-posting a position after it had ostensibly been filled was a red flag. In the words of one interviewee, “Hundreds of people apply, and then it’s re-posted again. What was the problem?”

Small organizations with only 1 or 2 existing employees that claimed to have achieved significant impact were also viewed with suspicion.

“I question how impactful a lot of these organizations really are.”

Inconsistent definitions

The most common complaint among interviewees was the lack of standardization around what “entry level” means in job announcements and stated requirements. The “Chief of Staff” role seemed to be particularly confusing as it could be either a senior or a junior role depending on the organization’s definition. Some even posted the same job at two different levels of seniority intentionally (e.g., “we’re looking for either a COO or a Chief of Staff”) which made it seem like the organization didn’t really know what they needed. Others spoke of being well-qualified for a role that should be entry level, but a PhD or 10+ years of experience was being asked for.

“Some companies don’t even consider you unless you have a master’s degree. So, you’re entry level at that company?”

Others mentioned that employers asked for so much in a job description, it seemed like the role should be more senior or better compensated. For example: operations roles that were delegated tasks a senior employee did not want to do including, in some cases, “standing in” for the executive in meetings, contributing to strategic planning, and writing in their “voice.”

Lack of feedback

The biggest barrier for many was the lack of substantive feedback offered by potential employers after a rejection. Interviewees spoke of not knowing why they were eliminated after devoting many hours to a work test or trial, nor what they could do to improve. Should they write better cover letters, reach out to more people, or acquire more technical knowledge? Not knowing which strategies would be effective led to many negative feelings including anxiety and discouragement.

“I’m positive that they have a clear hiring process, but within that clearness you get this classic email, your application is great but we decided to go with other people and there’s not a lot of feedback.”

Even when job seekers asked for feedback and received it, they didn’t learn much. Employers tended to provide mostly positive comments, perhaps in an attempt to make the rejected individual feel better about themselves. Interviewees spoke of not knowing whether it was the same problem that led to repeated rejections or something different each time.

Barrier 2: Preferences for Elite, Western Talent

Lack of elite credentials

Several individuals mentioned their lack of a degree from an elite institution was the thing that prevented them from landing a job, particularly for entry level positions that are the most competitive.

“The main thing missing from my profile, I have concluded, is a degree from a prestigious university like Harvard or Oxford.”

The perception that EA organizations were looking for an elite workforce demoralized some job seekers, particularly when this perception was reinforced by support organizations (for example, many spoke of being rejected for 80,000 Hours career counseling).

Lack of connections

There was a perception among interviewees that personal connections still matter more than performance in the application process and on work tests, even in EA. One interviewee mentioned that being involved in EA circles while at university was the ticket to an EA job. Two others mentioned the need to attend EAG in order to meet the right people.

“It’s hard to get access to organizations to learn about them and meet people. Even offering to volunteer is not well received.”

Economic barriers

The imperative to attend EA conferences also came up in discussion of economic barriers, as those from more disadvantaged backgrounds lack the financial resources or citizenship status needed to travel to these events. One interviewee said they lacked a reliable computer and internet access, and could only apply for jobs while at work, using their employer’s resources. Lastly, the multi-step application process which involved work tests and trials made the costs of applying particularly steep for some individuals, who could not afford to take time away from work or family commitments to proceed.

Simply being unemployed for too long was another financial pressure. When asked what would be most helpful to them in their job search, multiple subjects laughed and said, “A job.” Several spoke of their savings running out while they searched, and not having enough time to pick up the new knowledge or skills they felt some jobs required.

“At this point, I just need money. I haven’t had a full time job for years now.”

Geographic barriers

Others spoke of the inability to relocate to another country for a job, a problem particularly acute for those outside of the UK and the United States as many EA organizations are located there. Though remote jobs are an obvious solution, citizenship and time zone issues remain (along with the fact that these jobs are fiercely competitive).

“One of my criticisms of [the 80,000 Hours job board] is these great, interesting jobs are based in Europe.”

Inevitably, this will lead to more individuals from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) missing out on roles, further fueling the lack of geographic diversity in EA that some have written about previously on the Forum (for example, here), and opportunities to learn from these individuals’ experiences.

“A lot of EA organizations engage in the Global South, but it’s rare to see someone involved in the decision making. It’s rare to see, for example, an African person being involved. Consider how valuable it would be to involve people who have experienced that kind of stress. If you come from Harvard, maybe you haven’t had that experience.”

Solution 1: Actions for Job Seekers

Prioritize networking

“Every job I’ve ever had, I’ve gotten because I’ve known the right person.”

Multiple interviewees mentioned they were called back for more interviews after re-directing their attention from applications to networking. “Networking” included contacting people on LinkedIn who were second-level connections (making it more likely they’d respond), asking for feedback on their writing or research from people working in the field, and setting up informational interviews. Nearly half of those interviewed indicated a desire to learn more about networking and improve their skills.

Several interviewees thought that large conferences were important places to meet people but, surprisingly, did not indicate such opportunities had been useful to them in the past. I think this is important for two reasons: first, that networking encompasses a broad set of activities including, but not limited to, “working a room” at events; and second, it’s still possible to network successfully despite economic and geographical barriers.

Look for “side doors”

“It’s worth risking making the wrong impression to have any impression”

Simply applying for open positions is not enough to land a role. Several interviewees felt they made more progress by pursuing “side door” options such as starting an independent project that focused on a cause area of interest, volunteering, and freelancing. Others mentioned writing articles and blog posts on topics they wished to work on, though this could become time consuming. These activities helped job seekers get noticed, build a portfolio, and test their fit for different roles before committing full time.

Solution 2: Actions for Support Organizations

Support organizations such as 80,000 Hours and Successif were generally viewed positively and suggestions for improvement were very minor. However, several interviewees expressed a desire for more practical advice on how to break into new fields, meet the right people, and get hired. One individual interested in AI safety mentioned they would appreciate regular, 1:1 mentoring from someone working in the field who could advise them on how to improve their skills. Another thought that support organizations might connect them to other job seekers in the same cause area so they could help motivate each other and serve as “accountability partners.”

Two other specific suggestions that emerged from the interviews: 1) provide referrals to mental health support services, and 2) reduce the emphasis on applying for “operations” roles, as these roles appear to be the most competitive compared to technical roles.

Solution 3: Actions for Hiring Organizations

Before sharing specific suggestions, I’d like to make a case for why employers might want to consider evaluating and improving their hiring practices, even if they receive hundreds of applicants for each open role. First, organizations might consider how providing feedback to rejected applicants will help those individuals find high-impact careers elsewhere, thereby increasing the organization’s overall impact. Second, consider what rejected applicants might think and feel about your organization after going through your hiring process. Would they be motivated to continue engaging with your work in other ways, as donors, volunteers, or advocates? Lastly, look at the diversity (broadly defined) of your existing workforce. Are you creating opportunities for individuals from LMICs who could contribute meaningfully to your work, particularly if your organization operates in those countries? Are you employing people who are affected by the problem you’re trying to solve in general? It seems logical for organizations committed to Effective Altruism to regularly interrogate their own policies and practices to see if they are working as intended.

The following suggestions came directly from the interviews with job seekers. I don’t intend to provide additional supporting evidence for all of them, as this would be beyond the scope of my research. If those reading this post have additional evidence in support of, or against, any of these practices, I encourage you to share that evidence in the comments.

Focus on what’s actually required to do the job when writing position descriptions.[5]

If a role has an entry level title and salary, the responsibilities should be aligned accordingly.

Provide salary transparency. Job seekers deserve to know the ranges, as this is an important input in deciding whether to spend time applying.

Have explicit closing deadlines (rather than saying “open until filled”) so that candidates know when to expect a response.

Consider the first 100 applications and then close recruitment.[6]

Provide feedback whenever possible, particularly if a candidate has gone through multiple interviews and/or work tests.

Only contact references if you are seriously considering making an offer.

Conclusion

The process of looking for a job requires a tremendous amount of resilience, as repeated rejections and the absence of feedback can take a mental toll. Those who face economic and geographic barriers, and who lack social capital and connections, will have to work particularly hard to land a role. The results of this research suggest that focusing on networking and pursuing alternatives can open up new possibilities for job seekers that will help them progress toward their longer-term career goals. Most importantly, job seekers should recognize the competitive nature of EA organizations and consider carefully what “impactful” and “effective” mean to them personally (not just how they are defined within the EA community). Hiring organizations, for their part, might consider providing feedback to rejected applicants with the goal of steering more great talent into high-impact roles at other organizations.

Limitations and Mistakes

I didn’t collect demographic data out of a desire to make respondents feel more comfortable answering the survey. In retrospect, this was a mistake, as I was unable to say anything meaningful about how experiences differed across gender identity, race/ethnicity, and nationality. Another limitation is the exclusive focus on job seekers, which means the perspectives of hiring organizations, support organizations, and funders are missing. Lastly, because I conducted this research independently without support (and with life getting in the way), it took nearly a year to complete all the steps. If I had been able to publish earlier, the results could have been more helpful to the people I interviewed.

Appendix

Additional helpful resources

The audience for this post may be interested in learning what other EA-specific resources were mentioned, so I’ve listed them here along with the number of mentions in parentheses:

EA Slack Workspaces (3)

High-Impact Professionals (2)

Animal Advocacy Careers (1)

EA Facebook Group (1)

EA Forum (1)

Greater Good Science Center (1)

Impactpool (1)

Magnify Mentoring (1)

PCDN Global (1)

Training for Good (1)

Additional survey data

Themes from the “Other” comments included: AI alignment or philosophy (3 comments), co-founding or incubating startups (3 comments), absorbing information quickly (2 comments), networking or partnerships (2 comments), research (2 comments), and UI/UX design (2 comments). The following skills received only one mention each and are listed in alphabetical order: ecosystem development, longtermism, machine learning, moral decision-making, negotiating, neural network architecture, project management, technical skills, and tech policy.

There were 9 comments in the “Other” field, but no clear themes emerged. The following topics were mentioned: a need for support with finding mentors (2 mentions), help searching for the right roles, grants to pay for additional training, peer groups, and understanding labor market needs. Three of the “Other” responses were aimed at employer organizations and academic institutions: reduce ageism, provide more volunteer positions, and provide more career planning support to students while in college.

About the researcher

Julia Michaels is a self-described mediocre EA and mid-career professional. She has applied for 17 roles at EA organizations, was rejected from 15 of these roles, and withdrew her candidacy from 2 searches. Her alternative pathways to impact are volunteering for the EA DC group, donating to effective charities, and parenting two children who may someday have impactful careers. In her spare time she conducts unsolicited and unfunded research projects, such as this one.

- ^

What is an EA Organization anyway? Though this is not a clearly defined group, I used this map as a guide for organizations and initiatives that could be considered EA Organizations: https://whimsical.com/ea-relevant-orgs-and-initiatives-4EAx6c2MPbTRVjtjUBXfhx

- ^

For an overview of this method, see: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6318722/

- ^

For age, responses were nearly evenly divided between “too young” and “too old,” with some responses unclear (simply citing “age”).

- ^

Time zone differences prevented me from interviewing respondents in Asia.

- ^

A helpful resource on this topic from The Management Center: https://www.managementcenter.org/resources/must-haves-starter-kit/

- ^

An interviewee cited the “Secretary Problem” in support of this recommendation. Here is an overview: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Secretary_problem

- A Proposal For An EA Young Professionals Group by (19 Dec 2024 19:10 UTC; 20 points)

- 's comment on hbesceli’s Quick takes by (23 Jul 2024 6:00 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on Joseph’s Quick takes by (10 Jul 2024 21:03 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on What resources should job seekers know about? by (10 Jul 2024 20:43 UTC; 1 point)

A quick note regarding people who want help preparing for an interview: I’m happy to do a mock interview/practice interview, give feedback, and bounce around ideas. I’ve done this with a handful of people already, and they seemed to find it helpful.

Note that this would not be some kind of “divulging secrets that let you cheat/game the system,” but more along the lines of allowing you a practice your responses, getting frank/honest feedback, and to provide some suggestions for improving your chances.

Thank you Joseph!

A very half-baked thought: I wonder if we should encourage orgs to depend less on networking instead of encouraging applicants to network more? Networking seems to depend, at least partially, on a bias towards people you know and therefore like more. I suppose it may also increase trust in the applicant if mutual contacts can vouch for them and I don’t know where the balance of benefits / drawbacks lands.

It may be half-baked, but it strikes me as valid.

This is tricky, and for exactly the reason you would expect. The less networking is involved, the more fair/neutral/unbiased hiring tends to be, and the more fair/neutral/unbiased hiring tends to be, the higher quality employees you will hire (in expectation, of course). However, personal recommendations tend to result in higher quality employees than applications.

I hate the idea that John Doe doesn’t get a chance for a job simply because he couldn’t attend a conference, or because he wasn’t allowed into a gatekept group (a reading/discussion group, a student club, or even an informal social group). But I also hate the idea that organizations ignoring a source of high quality candidates, simply because they happen to be better networked/resourced than the average person.

It does sometimes occur that lots of people apply to a job, and none of them perform well enough to convince the organization to hire them. So while it is possible there is some sort of malfeasance going on, I suspect that the more likely scenario is simply that organizations have very high (or very specific) requirements.

We could certainly discuss to what extent this implies the organizations are being too picky, or the organizations are overly risk averse regarding false positives (making a hire that ends up not working out), or if the candidates really do lack the skills, or if something else is a major factor here. But I would be hesitant to suggest that the org is posting a “fake” job posting without additional evidence.

To be clear, I don’t think re-posted jobs are fake (although that was truly the perspective of one person I interviewed). Having been in the hiring manager chair enough times and overseeing several failed searches, it’s usually a) requirements are too specific, b) salary offered is too low, or c) the new hire didn’t work out—rare, but it happens. What I don’t know is whether EA jobs are re-posted more frequently than jobs in the rest of the universe. My guess is that it’s a universal problem but it would be interesting to find out for sure, and if that points to a more systemic problem (EA orgs consistently offering below-market salaries, for example).

I’m not sure whether ‘alternative’ was meant to be diminutive but, just in case, I want to say that donating effectively and organizing (and, possibly, other approaches) are fine and good and not merely a fallback approach. Not everyone in the EA movement is going to end up working for the EA movement.

Thanks for doing this research!

I expect that a major reason employers don’t like doing this is because hiring is a very imperfect science. Even the best hiring processes regularly result in rejecting qualified applicants for pretty stupid reasons.

I’m curious if you had any interviewees who received feedback that they thought was dumb and how it influenced their perception of the employer? I have a vague sense that people do actually feel better after having been informed that they were rejected for an arbitrary/ stupid reason, but I’m not sure if this is actually true.

You’re absolutely right. And not even for “stupid” reasons per se. As an employer I’ve found myself considering several finalists for a job and all 3 are great and can do the work...but at the end of the day, there can be only one hire and I just have to pick. It’s nothing personal. Where I think people are getting hung up is not necessarily feedback on why they didn’t get hired for a specific role, but not knowing what will help them improve their success rate in the job search overall. Because we all want to improve.

Looking back at my notes, I think what I observed across the interviews was that being ignored or getting a formulaic email reply was associated with feeling slightly antagonistic toward the employer (from what I can gather). Getting any kind of personalized feedback was appreciated, even if it wasn’t ultimately that useful. So I guess that kind of supports your theory that giving a stupid reason is better than no reason.

Personally, I’ll share that the most helpful feedback I got was from Charity Entrepreneurship (now called something else), after I explicitly asked for it. They said I wasn’t creative enough in my final interview and that was a core skill required for incubating a charity. I consequently stopped considering entrepreneurship as a pathway and refocused my energies toward finding a job, which was a big relief and (I think) helped me get hired faster.

I love that you spent the time to do this investigation and speak with people and consolidate the info here. I am biased (because I love hiring and social psychology and thinking about power dynamics and inclusion) but I really appreciate you putting in this work and sharing this post.

Hey Julia,

Thank you so much for doing this write-up, it’s really valuable. I just sent you a DM through the Forum because my organisation could be interested in contracting you for a short-term interviewer role, as part of our impact assessment.

I’m just putting it out here because I’m not sure how effective message notifications are on the Forum :) Plus, I might inspire/encourage others who were considering something similar when seeing good work on these platforms :)

I appreciate the initiative and helpful presentation of results! A lot of people want to work for an EA org, I think on the basis that this action seems extremely EA-approved and charting your own impactful career path seems very nebulous and daunting. I fairly frequently repeat something like “okay but I want you to pay attention to the mountain of rejected EA resumes over here”, so I appreciate this resource and novel reporting about how people actually felt about the process.