Theories of Change for Track II Diplomacy [Founders Pledge]

You can find a PDF version of this Founders Pledge report here.

With thanks to Tom Barnes, Stephen Clare, Oliver Guest, Matt Lerner, Rani Martin, Conor Seyle, Sharon Weiner, and others for their helpful input and feedback on this project.

Background

At Founders Pledge, we have made or advised on grants to several track 1.5 and track 2 diplomatic dialogues:[1]

U.S.-China dialogue organized by Carnegie China ($100,000)

U.S.-China AI dialogue organized by Brookings ($100,000)

U.S.-China AI dialogue for a session on AI-bio risks organized by INHR and CACDA (€115,000)

U.S.-China dialogues on strategic nuclear risks organized by Pacific Forum and CFISS ($200,000)

U.S.-China-Russia dialogues tied to Project Averting Armageddon at CEIP (part of a larger $2.4 million grant)

U.S.-China-Russia dialogues tied to a RAND project on dual-use risks in space (part of a larger $3 million grant)

Additionally, we recommend funding FarAI, which acts as an umbrella organization for the International Dialogues on AI Safety. Previous Founders Pledge research reports have outlined some of the reasons for supporting track 2 diplomacy.[2] For example, Stephen Clare gave a brief “Theory of Effectiveness” on p. 117-118 of Great Power Conflict.[3] We have not, however, given a complete public overview of ways to conceptualize the impact of track 2 dialogues. Moreover, other public discussions of the value of track 2 diplomacy are often extremely fuzzy, and cite ideas of “finding common ground” and “shared interests” and “building trust” without explaining what this means mechanistically and how it leads to desirable state-level outcomes.

Reviewing the literature and history of track 2 diplomacy and using interviews with dialogue organizers, participants, and current and former policymakers, this document outlines various theories of change that both private philanthropists and government funders who support track 2 dialogues can use in evaluating proposals and making funding decisions.[4] Importantly, this document is intended to outline the potential ways that track 2 dialogues can work, not to make a definitive case for their effectiveness (although I briefly sketch why we fund track 2 dialogues).

I outline several related theories of change, which often overlap:

Transparency, Trust, and Information Exchange

Object-Level Problem Solving and “Diplomatic Subsidy”

Developing Expert Communities and Government Talent Pools

Supporting Track 1 Diplomacy

Hedging against Political Change

Raising Issue Salience for Policy Stakeholders

Establishing Backchannels for Crisis Communication

These theories of change all touch on an overarching model built around the movement of ideas and people through porous and complicated policymaking ecosystems. I have outlined this overall model of how non-state dialogues can influence state-level decision-making in the diagram below:

Track 1.5/2 Policy Ecosystem Model

The following sections all seek to unpack this model, and explain the different levers of risk reduction in the form of the theories of change outlined above.

Following these theories of change, I then turn to their implications:

The leverage of track 2 dialogues (Why we fund track 2 dialogues)

The importance of issue area choice

The importance of convening power and policy networks

The spectrum of track 1.5-2

The risks of dialogues and how to protect against them

Transparency, Trust, and Information Exchange

The first theory of change for track 2 dialogues relies on the interaction of transparency, trust, and information exchange.

Proponents of track 2 dialogues claim that they can help to disrupt misperceptions and dangerous spirals in international relations by facilitating the exchange of information and increasing transparency.[5] This matters because information asymmetries on adversary capabilities and intentions contribute to the role that great power competition plays in driving catastrophic and existential risks.[6] One classic formulation of the risks of information asymmetry is the “security dilemma,” in which mutual distrust and lack of transparency can drive arms race dynamics.[7] In a simplified version of this dilemma, states feel insecure, and thus take security-seeking actions. Rival states in turn view these actions with suspicion and feel less secure, fearing offensive intent and capabilities. These states thus respond with their own security-seeking actions (e.g. building up armed forces), sparking a spiral that leaves everyone less secure, even though there was no hostile intent from either party.

Testimony from Soviet defectors suggest that similar dynamics were at play in the perpetuation and expansion of Biopreparat, a part of the USSR’s biological weapons program during the Cold War. After the Nixon administration renounced biological weapons and signed the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention, decision-makers in the communist party-state apparently viewed this as a potential ploy to disarm the Soviet Union and continue a covert weapons program. Ken Alibek, for example, claims to have viewed continuing defensive work at Fort Detrick as evidence of a larger offensive U.S. program, writing that the Soviets believed that “Even if our intelligence activities couldn’t come up with concrete evidence of offensive work, there could be no doubt that such work continued.”[8] In turn, the Soviets engaged in the largest biological weapons program in the history of humanity. Had there been greater exchanges between experts, including information exchange that could show defensive intent, perhaps this tragic development could have been avoided.[9]

Such spiral dynamics may be part of the current U.S.-China relationship, which one recent RAND report characterized as a “spiral of hostility.”[10] Both sides read hostile intent into vague “strategies” like “a free and open Indo-Pacific” (U.S.) or “a community with a shared future for mankind” (China), and respond with actions that only seem to worsen mutual mistrust.[11] This is especially important for those philanthropists and organizers who are most worried about “racing” dynamics on high-consequence emerging technologies like AI.[12] (See Great Power Competition and Transformative Technologies for more detail.) The potential for over-estimating adversary capabilities is especially pernicious in fields where independent verification (e.g. via satellite imagery) is difficult, like software-based capabilities (though necessary hardware infrastructure may still leave detectable footprints), and for general-purpose technologies where dual-use dilemmas are inherent to the technology.[13]

Using the model outlined above, track 2 dialogues can act on the internal threat-assessment processes of participating countries, which in turn affect policy and decision-making processes:

In practice, information from track 1.5/2 dialogues is going to be assessed in the context of other processes that can confirm or disconfirm track 1.5/2 information:

We can also visualize the effect of decreased uncertainty, which in turn affects the decisions and policies of both countries:

(Note that although we refer to the intentions or capabilities of a state, this theory of change does not rely on a unitary actor model of international relations. Rather, track 2 dialogues can affect different parts of a messy bureaucracy, including intelligence assessment, policy planning, and execution. Referring to a state’s “uncertainty” or “mistrust” is merely shorthand for this complex process and the aggregation of thousands of decisions and perceptions, some of which may be affected by track 2 dialogues.)

It is important to note that although “spiraling” dynamics and the security dilemma are arguably among the most important factors in the U.S.-China relationship, transparency and information exchange can affect this relationship in other ways. For instance, given cultural and ideological differences, both sides may think that their signaling is clearer to the receiver than it actually is. As the RAND report cited above (drawing on Robert Jervis’s work on misperceptions) puts it:

“both U.S. and Chinese officials appear regularly frustrated that what they see as a simple and clear message is not being understood by the other side. When the reaction is negative or untrustworthy, this leads them to impute hostile intentions to the other side.”[14]

Track 2 dialogues may help to dislodge such perceptions, in part by showing just how confused each side is about even basic facts about the other’s political system.[15] Compared to other information-exchange mechanisms (e.g. international scientific journals), track 2’s interpersonal element may provide more and richer information (including non-verbal information – see below on body language), more avenues for the confidential exchange of information, and more opportunity to build trust and assess trustworthiness.

The information exchange at track 2 dialogues can be especially beneficial when dealing with countries that are less transparent on information or do not publish their doctrines and strategies on key issues.[16] During the Cold War, for example, as Matthew Evangelista has argued in his book on Pugwash’s transnational advocacy, “in the realm of security policy, even basic data on the relative balance of U.S. and Soviet military forces were so closely held that Soviet moderates depended on their transnational contacts to provide such information.”[17] This ability eventually facilitated the moderates’ victories in policy debates under Gorbachev.[18] Similarly, according to recent Reuters reporting on the Pacific Forum U.S.-China nuclear dialogues (funded with a Founders Pledge-advised grant), Chinese delegates “offered reassurances” that “they would not resort to atomic threats over Taiwan.”[19] (Of course, such claims cannot be taken at face value and need to be examined carefully, as discussed below.) At times, information exchange can take the form of education, with one side teaching the other key concepts about the issue in question to reach common understandings on key ideas, like deterrence.[20]

Importantly, this information exchange need not be voluntary or explicit, and it does not need to rely on the honesty of interlocutors. Track 2 dialogues can facilitate a great deal of information exchange, including clues like:

Who attends? What does this imply about the prioritization of the issue area within the rival state? What “NGOs” are closest to the levers of power?

Who defers to whom? Subtleties like speaking order and self-arranged seating can help provide clues about the most important voices on a specific issue, and whose opinions are likely to matter most in the coming years, e.g. Is an eminent safety-focused AI scientist treated with respect or is she ignored?

Body language. Involuntary facial expressions and other body language can provide clues about e.g. what arms control proposals can be discussed in official settings (see “Supplementing track 1 diplomacy”, below).[21]

And more.

Organizers of dialogues have explained that this kind of intelligence collection and subsequent briefing of host governments are understood and expected.[22] Both sides tend to have an unspoken agreement that they will be briefing their country’s officials, even if no officials are present at the dialogue — as discussedbelow, this suggests that the border between “track 2” and “track 1.5” is fuzzy. For example, an official participating in U.S.-China track 2 dialogues on AI-bio risks (funded by Founders Pledge’s GCR Fund) recently told DefenseScoop that

“I’m sure every meeting we have somebody whose job it is to collect information on us, as well. That’s okay. We actually want to impart information. And it’s faster if they write a report and send it directly through their intelligence.”[23]

Notably, we do not want to facilitate spying or the transfer of non-public information. Rather, we want to provide a rival state with assurances and a more accurate assessment of non-threatening intentions, and sometimes this reassurance may run via intelligence channels.

This theory of change suggests an important attribute for dialogue conveners and participants: they need to be able to reach key decision makers, via briefings, written readouts, or personal connections. In other words, effective track 2 dialogues may need to be de facto track 1.5, if not by inviting government participation, then by facilitating backchannels and briefings to relevant stakeholders in the policy ecosystem. The key links are highlighted in red in the following diagram:

Doing this responsibly requires the ability to verify information, or to update appropriately based on the strength of new information. For example, organizers could triangulate information from different sources and dialogues, and see whether it suggests true information. Participants may simply ask their interlocutors, “how do I know what you say is true?” which may point towards credible means of verification. Similarly, intelligence analysts can verify information gleaned from dialogues using other means (e.g. if observed trends in computational hardware supply chains match claims made about the existence or non-existence of large AI projects). Additionally, good dialogue organizers may “hotwash” participants afterwards in order to help guard against potential attempts at disinformation.

The benefits of transparency and information exchange via track 2 dialogues are not limited to each other’s capabilities and intentions, but can also concern third parties and changes in the state of the world. For example, if U.S. experts became aware of a major technical breakthrough in synthetic biology that they felt increased the risk of terrorist misuse (but had no effect on state capabilities), they may wish to share this with their Chinese counterparts who are equally concerned about misuse of the life sciences (See also Establishing Backchannels for Crisis Communication, below). Transparency and information exchange may also include the exchange of “best practices” on certain issues, contributing to object-level problem solving. For example, state A may share best practices on nonproliferation or access control with state B, because both states have an interest in preventing terrorist groups or other rogue actors from gaining access to powerful technologies and weapons systems.

This document focuses mostly on governments, given their leverage and influence, but certain benefits of information exchange may also apply to private industry and the scientific community, especially in fields where the private sector currently leads (such as frontier AI firms).

Information exchange, finally, may also include work to find shared definitions and concepts, building lexicons that can both help to avoid misunderstandings and potentially lay the groundwork for more fruitful track 1 diplomacy.[24] The Brookings-Tsinghua CISS U.S.-China dialogue on AI has helped both sides develop a common understanding of key terms like “autonomy,” which may influence the official U.S.-China track 1 talks.[25] Finally, transparency and information exchange, supporting trust and confidence building, may also include joint statements on the perceived need for cooperation on specific issues, like Fu Ying and John Allen’s statement on AI.

Trust and confidence are closely related to transparency and information exchange, but conceptually separate; we can have information exchange with little trust.[26] Mistrust fuels misperception and is especially important because many of the capabilities that are relevant to extreme risks are inherently dual use. For example, biodefense investments could easily be mistaken for a covert offensive biological weapons program, as described above. Similarly, AI alignment methods such as reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) may help improve safety, but also demonstrably make systems more useful; just as a government biodefense program can have offensive uses, a future government AI safety program can accelerate strategically-useful capabilities.[27]

Trust, although a fuzzy concept, plays several important roles in disrupting the security dilemma and the ways it can drive extreme risks:

Setting the level of mutual suspicion that drives security dilemmas and arms racing.

Calibrating belief in exchanged information. Trust in one’s interlocutors can play an important part in determining how much to update based on new information obtained in dialogues.

Put in Bayesian terms, trust affects both the prior and the strength of the update. Importantly, dialogues can affect trust in both directions. It is possible that one’s interlocutor really is dishonest, cannot be trusted, has hostile intent, and is likely to pursue dangerous technologies without regard for safety and proliferation risks. This, too, is valuable information that should affect strategy on technology competition of safety-oriented actors.[28]

Some proponents of track 2 diplomacy point to the social psychology literature on “intergroup contact theory” (ICT), the idea that contact between members of different groups can decrease prejudice, increase empathy, and decrease conflict.[29] This 70-year-old theory originally developed out of experiments on racial prejudice in contexts like student settings (e.g. assigning White and Black students in the same dorm room and surveying changes in attitudes), and has since been applied to other contexts. In a review of this experimental evidence, Marianne Bertrand and Esther Duflo (2016) concluded that “inter-group contact is an effective tool to reduce prejudice, even though more work remains to be done to ascertain the specific conditions under which contact will be most effective.”[30] One 2006 meta-analysis on intergroup contact theory concluded that these effects are likely real and that “greater intergroup contact is generally associated with lower levels of prejudice (mean r = –.215).”[31] I remain somewhat skeptical of the measurements of prejudice used in many of the underlying studies, but the analysis actually suggests that “Higher quality of the contact and prejudice measures tend to show larger average effect sizes for samples in both subsets.”[32] It is not clear how well these findings transfer to inter-state conflict, however; prejudice may or may not be a major factor in disputes (there are also structural issues and genuine conflicts of interest). Moreover, it is unclear how individual attitude changes would translate to group attitude changes on a national level. Because of these considerations, combined with the general unreliability of many published research findings (including meta-analyses), especially social psychology, I do not rely on ICT in this write-up, even though it is popular with many track 2 conveners and funders.[33]

Trust in people of the kind supposedly fostered by intergroup contact is not necessarily required to increase confidence in information, however, as track 2 dialogues still provide new updates and intelligence. If information from many different track 2s is analyzed together with real-world data (e.g. satellite imagery), we might be able to find patterns and triangulate claims, thereby increasing our ability to accurately judge capabilities and intentions.

Nearly every organizer and participant in track 2 diplomacy that I have interviewed emphasized the importance of in-person convenings for building trust and confidence. Frequent allusions are made to “side conversations” and the “real progress” happening “at the bar.” Videoconference is not conducive to these kinds of conversations (and is more vulnerable to eavesdropping). For example, Chinese participants are often likely to read prepared statements at the official sessions, following the official Party line, but may be more likely to speak candidly during side conversations.[34] Several suggested that evening alcoholic drinks are especially useful in stimulating frank exchange.[35]

One implication of these points is that the returns of putting thought and resources into the space and experience of the dialogues may be large. That is, good hotels, business-class flights for participants, catered meals, a space that feels comfortable and secure, and — where culturally appropriate — subsidized alcoholic drinks, may not just be extravagances, but may create the kind of environment that is conducive to:

Attracting high-level participants — The influence of participants matters, as described above. Some participants may simply be more likely to attend extravagant dialogues (e.g. because they are used to a certain lifestyle, or because they view it as a sign of respect).

Creating the opportunity for frank exchange — The apparent “frills” of a dialogue (the coffee breaks, the cocktail hours, the dinners) may actually be more important than the official sessions in some cases.

Similarly, multi-year funding for repeated exchanges with the same participants could help to build this trust more effectively under this theory of change. It can be tempting to dismiss dialogues with high price tags, especially given the counterfactual value of philanthropic money — helping the global poor, curing diseases, advocating for animal welfare, etc. If it is true that high-end dialogues are high-impact dialogues, however, then cheaper dialogues are not necessarily more cost-effective.

Object-Level Problem Solving and “Diplomatic Subsidy”

Track 2 dialogues can also engage in object-level problem solving for the issue at hand.[36] AI safety dialogues, for example, may discuss key ideas around safety, evaluations, red teaming, and more, and may exchange “best practices” on each. Track 2 dialogues can facilitate finding technical solutions to political disagreements, for example, or they may hammer out the details of a potential international agreement. They may discuss different legal interpretations of existing international law and how it applies to new technologies.[37] At times, participants in track 2 dialogues may actually help to draft the international agreements — treaties, confidence-building measures, and others — that are then refined in track 1 diplomacy. (Object-level problem solving may, however, not be possible in early stages of dialogue, when information exchange dominates.[38] This suggests that there may be “stages” of a dialogue, and again shows the value of multi-year support.[39])

One prominent example of object-level problem solving achieved by track 2 dialogues was the technical solutions that Pugwash dialogue participants found to problems of monitoring nuclear tests that led to the Limited Test Ban Treaty.[40] Both sides needed a way to distinguish natural events (earthquakes) from secret nuclear tests, but Soviet participants reacted negatively to the U.S. proposal of manned inspections. Both Kennedy’s Presidential Science Advisor Jerome Wiesner and the head of the Atomic Energy Commission Glenn Seaborg credited Pugwash with a breakthrough by proposing a technical solution to the problem: using “black box” seismic detectors.[41] (In this case, the technical solution was not ultimately used, but helped to advance the then-deadlocked discussions that eventually led to the Limited Test Ban Treaty.)[42]

In this sense, we can view track 2 dialogues as a form of “diplomatic subsidy.” In political science, the concept of “legislative subsidy” is most associated with the idea that lobbying is sometimes “an attempt to subsidize the legislative resources of members who already support the cause of the group. In short, lobbying operates on the legislator’s budget line, not on his or her utility function.”[43] “Diplomatic subsidy” is an analogous concept, where non-governmental experts and negotiators do the government’s work for them. Doing so may be necessary because diplomats are often too busy with the urgent to deal with the important, because diplomacy is under-funded, because government experts lack necessary expertise, because dialogue with “the enemy” is a political non-starter, and for many other reasons.

The Diplomatic Subsidy and the Role of Funders

Because track 2 diplomacy can provide this diplomatic subsidy and solve many problems before official negotiations begin, some practitioners of track 2 diplomacy actually view track 1 diplomacy as a mere discussion of “administrative details.”[44] Relatedly, discussions of the effects of track 2 dialogues also often point to their effects in the building and “socialization of an epistemic community of experts.”[45] In her discussion of Middle East track 2 efforts, for example, Dalia Dassa Kaye argued that the main effect of track 2 dialogues is the creation of “a vast network of influential policy elites who are more receptive to ideas supportive of cooperative security and dialogue.”[46]

Of course, there is always the possibility that the participants in track 2 dialogues simply fail to solve the object-level problem or propose intractable or even counterproductive solutions. Nonetheless, there are several reasons to think that the decision-making apparatus of “government + track 2 diplomatic subsidy” is likely to be superior to the government decision-making apparatus alone:

Increased technical expertise — Government officials are notoriously bad at retaining scientific and technical experts, and often lack basic understanding on the technologies they are supposed to be regulating.[47] Track 2 dialogues can draw on the technical expertise of participants to improve decision-making.

Increased epistemic diversity — Relatedly, track 2 diplomatic subsidy may increase the epistemic diversity of the decision-making apparatus overall, potentially injecting valuable variance into a process otherwise ruled by government group-think.

Increased time for deliberation — In government, the urgent often crowds out the important. If increased time for deliberation is likely to improve decision-making, then track 2 participants can use their time to work on the most important problems.

There is, however, a risk of elevating one group of experts over the rest of the relevant community, potentially promoting only a subset of the loudest voices.[48] Funders will need to ensure that their portfolios reflect a diversity of viewpoints and cover as much of the solution-set as possible (or they need to have high confidence in certain communities). This is especially important because, as the next section explains, track 2 dialogues can help to develop talent pipelines to relevant governments.

Developing Expert Communities and Government Talent Pools

The diplomatic subsidy for complicated issues like AI and biosecurity is especially important because technical expertise on certain topics is in short supply in Western governments. In the U.S., U.K., and Europe, for example, the shortage of AI talent appears to be hindering the ability to develop thoughtful policy and craft well-tailored AI regulations.[49] If AI governance expertise is in short supply, then a valuable subset of that expertise — U.S.-China relations and AI governance — is in even shorter supply. Thus, attendees of track 2 dialogues may be in high demand when crafting policy that is relevant to U.S.-China relations and AI.

The development of these expert communities, in turn, can beneficially affect the decision-making process in bureaucracies, especially if the attendees of these dialogues develop a more true understanding of their rivals’ intentions and beliefs, decreasing the probability that decisions will be misperceived. Matthew Evangelista also emphasizes the importance of “transnational policy coordination,” the ability to better coordinate domestic and foreign policy in order to achieve risk-reducing measures.[50] Thus, for example, one side can communicate to the other that there is an open policy window in their host country, and that the time may be ripe for a track 1 diplomatic approach. Sometimes, this allows the expert communities to leverage each other’s comparative advantages; as Evangelista explains, at times during the Cold War when U.S. scientists were not close to the policymaking process but had detailed knowledge of the risks, Soviet scientists had less knowledge but greater access.[51] Importantly, these communities can also continue to communicate with each other, including in times of crisis, as explained in the section on crisis communication.

Moreover, these communities can subsequently help to fill talent gaps in governments. Former track 2 dialogue participants may be the best-equipped to understand the problem as well as the rival state’s approach to the problem. In this way, the development of expert communities also linked to the next theory of change: supporting track 1 diplomacy:

Supporting Track 1 Diplomacy

Many organizers and funders of track 2 diplomacy appear to view the “maturation” of their dialogue into track 1 diplomacy as the ultimate goal of their dialogues.[52] Indeed, track 2 diplomacy can lead to track 1 diplomacy in a number of ways. They may, for instance, simply demonstrate that dialogue is possible, and that the other state is interested in engaging further. They may also do much of the heavy lifting for diplomats (again, a kind of “diplomatic subsidy” for an under-resourced government) and provide ideas in what practitioners of track 2 diplomacy call “transfer.”[53]

Jones cites the Harvard psychologist Herbert Kelman, whose track 2 process is credited with leading to the 1994 Oslo Accords, in outlining three ways that track 2 can build foundations for track 1 diplomacy:

“Developing cadres of people who may take part in future official negotiations”

“Providing specific substantive inputs into a negotiation process, or even discussion about the possibility of negotiations.”

“Developing a political environment in which negotiations may be possible.”[54]

There are several historical examples of track 2 dialogues that matured into track 1 discussions:[55]

Pugwash Conferences during the Cold War, which is credited with having influenced or led to several arms control treaties, including the Limited Test Ban Treaty, the SALT talks, the 1972 Anti Ballistic Missile Treaty, and possibly the Biological Weapons Convention.[56]

Herbert Kelman’s off-the-record meetings between Israelis and Palestinians throughout the late 20th century, credited with leading to the Oslo Accords.[57]

U.S.-Iran track 2 dialogues that led to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).[58]

Self promotion makes some of these claims difficult to evaluate, but the evidence that Pugwash at least was a major forum related to developments that led to the LTBT, for example, appears strong.[59] The theory of change here is that track 1 diplomats actually have the authority and power to help negotiate agreements between states, and thus the “maturation” of track 2 discussions into track 1 discussions allows the “real impact” to take place.

Track 1 diplomacy need not always displace track 2 efforts, however. Some track 2 dialogues can also supplement ongoing track 1 effort.[60] This is sometimes called “hard” track 2.[61] For example, a former official from the Founders Pledge-funded AI-bio dialogue mentioned above told Defense Scoop:

“Good Track 2 dialogues have some connection to Track 1s — [often] through former officials like myself and [General Jack Shanahan], who can just go talk to our old colleagues and basically debrief over a beer. You can tell people that you know what you’re working on, and you hope the same thing happens on the Chinese side.”[62]

One person I interviewed for this project, for example, referred to the idea of “trial balloons” in track 2 diplomacy. State A’s officials may suggest that track 2 participants “float” a certain idea, in order to gauge state B’s interest. Depending on whether this idea turns out to be in or out of bounds, track 1 diplomats may then raise the idea in the official dialogue. This de-risks track 1 diplomacy, helping to avoid diplomatic embarrassments that could set the official discussions back, and helping to find practical workarounds to official impasses.[63]

Similarly, while track 1 diplomacy is ongoing, track 2 diplomacy can continue to provide the diplomatic subsidy discussed above, especially on highly technical topics (like the governance of emerging technologies). Track 2 diplomacy may include technical experts who lack diplomatic skill and authority, but whose insights and understanding are critical for the details of track 1 agreements.

For example, as the U.S. and China launch official track 1 diplomacy on AI, Brookings explicitly frames its ongoing dialogue with Tsinghua CISS as a complementary track of diplomacy, writing:

“As governments take up this cause, the Brookings-Tsinghua CISS Track-2 dialogue will continue apace. This unofficial dialogue will help identify areas ripe for U.S. and Chinese interaction, while also developing a body of public knowledge around opportunities and risks related to the employment of AI-enabled national security capabilities.”[64]

Some scholars of track 2 diplomacy have suggested that empirical evidence shows that multi-track approach is more effective than track 1 diplomacy alone. In one of the few attempts to quantify the effects of different tracks of diplomacy (specifically on conflict mediation), Tobias Böhmelt suggests that track 1 diplomacy is generally more effective than track 2, but also that “T1 mediation is more effective when it is facilitated by unofficial tracks,” suggesting that multi-track diplomacy increases effectiveness by a factor of 1.2 compared to track 1 diplomacy alone.[65] While this and similar analyses may provide some evidence, however, it is weak evidence. We should not update strongly on correlations between the existence of multi-track diplomacy and positive outcomes, given the many selection effects and confounding factors at play.[66]

Hedging against Political Change

Track 2 diplomacy can also help to hedge against partisan changes that would otherwise routinely disrupt progress.[67] This may be especially important for democratic countries with term limits (e.g. the United States), whose frequent leadership changes could make them difficult negotiating partners for multi-year efforts on specific problems of international cooperation, but can matter for any country that experiences regular change in leadership and/or priorities.[68] Track 2 diplomacy can also help to protect against diplomatic breakdowns in general, preserving progress and also facilitating crisis communication when normal channels are not being used.[69]

Using the example of U.S. politics, for example, consider the following example:

In the 2 years leading up to a presidential election, both track 1 and supplementary track 2 dialogues make substantial progress on mitigating risks from emerging technologies.

The U.S. president, however, loses their re-election, and their replacement has no interest in facilitating cooperative dialogue with rival states.

Nonetheless, the technology in question is advancing rapidly, and international cooperation appears necessary.

In this world, the track 2 dialogue can continue, perhaps incorporating the newly-unemployed political appointees that participated in track 1 dialogues.

After 4 years, the President’s party loses power, and official diplomacy can continue.

Thanks to the ongoing track 2 dialogue, diplomacy does not need to start over, and may even have made significant progress.

This is conceptually similar to the idea of a “shadow cabinet” in some parliamentary systems, and closely tied to the role that partisan think tanks can play in the United States in assembling a “government-in-waiting.” Track 2 organizers need to be very clear, however, that they are non-governmental and unofficial (and should continue to inform home governments of their activities), to avoid misperceptions and because the Logan Act of 1799 criminalizes certain unauthorized diplomatic negotiations (similar restrictions may or may not apply to actors in other jurisdictions).

Some track 2 dialogues seem to have a slight liberal bias.[70] It may be especially useful to support dialogues that include right-leaning participants to help stabilize risk-reduction efforts across changing administrations or — ideally — to conduct bipartisan or nonpartisan dialogues to help avoid politicizing important issues. This is especially important because of the role that the U.S. Senate plays in treaty ratification in the United States, and the observed pattern that Republican Presidents have a strong advantage in getting treaties ratified (allegedly because Republican Senators tend to vote along partisan lines, and Democrats tend to favor arms control no matter what).[71]

In the worst case, some administrations may even make it difficult to conduct track 2 dialogues with China at all. This possibility may mitigate the benefits of political hedging, but it may also raise its importance — if there are advocates for the importance of continued track 2 dialogues in any given administration, then the probability of dialogues being restricted may be lower.[72]

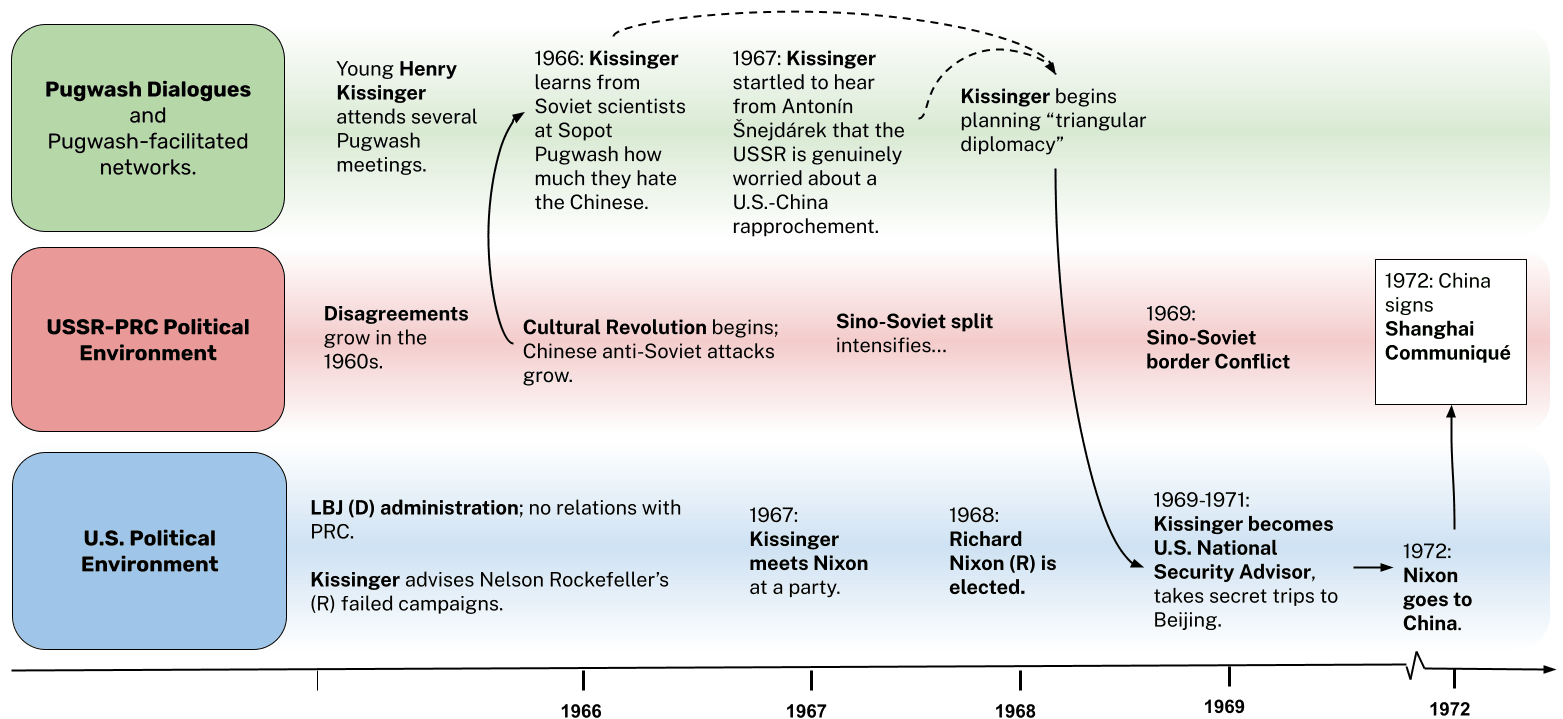

One example of how track 2 dialogues can facilitate opportunities when the political winds change is illustrated by Niall Ferguson’s account of the role that Pugwash played in the formation of “triangular diplomacy” and ultimately the normalization of U.S. relations with China. Kissinger, who attended several meetings of Pugwash in the 1960s, started noticing in 1966 that Soviet attitudes towards China clearly soured, and that a Sino-Soviet split was beginning to intensify. Via Pugwash, Kissinger was invited to Prague, where he was surprised to hear from Antonín Šnejdárek (involved in Pugwash and Czech intelligence) in 1967 that the Soviets actually worried about a possible U.S.-China rapprochement. In the meantime, Kissinger’s favored Republican, Nelson Rockefeller, lost to Nixon, and in 1969, Kissinger became National Security Advisor and the Sino-Soviet split turned violent in the border conflict. Pugwash provided the networks and seeded the idea of triangular diplomacy in Kissinger’s mind, and then political winds aligned to make such diplomacy.[73]

Ultimately, I don’t think we can confidently ascribe counterfactual impact to Pugwash in this case. I think it’s very plausible that Kissinger would have just used his historical knowledge of the European “balance of power,” or even that the opportunity for triangular diplomacy would have been obvious to any national security advisor at that time. Nonetheless, this example still illustrates the principle of how unofficial diplomacy can help diplomats build networks and knowledge that they can then use beneficially when the political context shifts.

Raising Issue Salience for Policy Stakeholders

Busy diplomats and bureaucrats are reactive by necessity, and thus the urgent often crowds out the important. Private individuals and philanthropists, on the other hand, have the time and the resources to engage in more far-sighted thinking, and identify threats that could arise in the coming years, rather than weeks. Track 2 diplomacy can be one efficient way to raise alarms about threats looming on the horizon that busy bureaucrats do not know to worry about. This may also be a factor of a lack of expertise on certain technical topics (like artificial intelligence).[74]

For example, scientific experts may realize that a certain near-future technology will soon facilitate the proliferation of WMD. They also believe that the regulation of this technology needs to be global (or at least involve the major powers) in order to be effective. Track 2 dialogues provide one avenue for raising the salience of this problem in multiple relevant jurisdictions at once. Thus, track 2 diplomacy can be partnered with policy advocacy to raise issue salience and simultaneously lay the groundwork for international cooperation (rather than waiting for the government to do so). Issue salience can be raised via the backchannels and policy transfer above, or via more public means, such as joint statements, such as the joint IDAIS-Beijing statement on AI risks and safety. Such joint public statements may exert stronger pressure on governments, and may be especially useful for dissuading fears that one side will fall behind the other, or even that one side is trying to manipulate the other into slowing down development of transformative technologies.[75]

Moreover, track 2 dialogues are one of the only levers available to philanthropists to influence policy in closed societies.[76] In countries like the United States, think tanks, academics, and other civil society actors all contribute to a marketplace of ideas, where philanthropists can help to support those ideas most likely to benefit humanity (especially when there are market failures or misaligned public policy incentives). In more authoritarian countries like China, however, directly funding policy-focused organizations working on important problems may not be possible or desirable, for a variety of reasons:

Legal restrictions on the use of philanthropic funds

The suspicion of “influence operations” if a project is funded by Western funders who have previously funded security-oriented organizations

A lack of understanding of the Chinese policy making process

The risk of funding harmful activities or subsidizing sensitive technologies

A distaste for funding organizations that are inevitably linked to the Chinese party-state.

Track 2 dialogues provide a means to raise the salience of key issues without some of these hurdles (depending on the specific case, some issues may still apply[77]). It is well-known that so-called non-governmental participants in fact have close ties to the Chinese party-state, and that participants on both sides will often work closely with their respective governments. Scholars of track 2 dialogues have traced this development in detail in the case of Pugwash and the ABM treaty and its influence on the Soviet government:

Source: Based on discussion in Pugwash Literature Review, citing Matthew Evangelista, Unarmed Forces.

This theory of change is, in my opinion, the strongest of the ones I have discussed here, and also the one that is least-discussed in published writings. It is strong because it can influence policy in multiple countries with limited expense. It can find shortcuts to the (very) expensive and circuitous problems of policy advocacy in crowded fields, and instead bring the issue directly to the attention of eminent scientists, elder statesmen, and other influential persons, and give the entire effort an aura of authority and legitimacy (especially if it is held in an impressive setting, with a highly selective group of invitees, etc.). It also allows a more high-fidelity translation of ideas and solutions, because the route to decision-makers is shortened, and thus the opportunities for misinterpretation and oversimplifaction are decreased.[78]

Influence in the Chinese Party-State Intuitively, we might be skeptical of the claim that track 2 dialogues could have an impact on the decision-making apparatus of the Chinese party-state. In this box, I briefly discuss structural reasons to think that track 2-mediated advocacy could be especially influential in China. My initial skepticism was driven by the expectation that policy influence requires an open civil society. As Matthew Evangelista writes in his assessment of transnational advocacy during the Cold War (in the USSR context), “In a political system dominated by a strong party-state apparatus, such as the Soviet one, societal forces, including transnational actors, should exert little influence on policy” in theory.[79] And yet, Pugwash was apparently highly influential, contrary to what such a view would predict: “It seems surprising that foreign citizens, engaged in transnational networks, should have been able to influence such an authoritarian and insular state as the Soviet Union.”[80] Evangelista — by carefully tracing the movement of ideas, as I sketched them above — argues that in fact, this structure sometimes facilitated impact: the “high centralization of the system and the enormous power and authority concentrated in the Politburo and in the person of the general secretary are the main characteristics that fostered the promotion of innovations,” even in the face of strong internal opposition from the Soviet party-military-industrial complex: “the support of the general secretary allowed policy entrepreneurs to prevail against strong institutional opposition.”[81] The People’s Republic of China is very different from the Soviet Union in countless ways, and we should not be too quick to apply lessons from a Cold War context to the contemporary U.S.-China competition. How much these considerations apply is a major uncertainty.[82] Nonetheless, structurally, the Chinese party-state was explicitly modeled on the Soviet one, complete with a Politburo and a general secretary.[83] With recent changes in this structure under Xi Jingping towards even greater centralization of power, we might expect similar dynamics of influence to work in China as worked in the Soviet Union via Pugwash. |

This issue-salience-raising is relatively cheap, and at worst on-par to the costs of organizing think-tank workshops or policy roundtables for domestic policy advocacy. The costs of dialogue are small in comparison to domestic policy advocacy. Usually, the costs include:

Venue costs (hotel rooms and conference rooms for a week)

Airfare and other travel costs

Meals and drinks

Preparation costs (e.g. preparing pre-reading materials)

Possibly small honoraria for participants

The costs of organizing pre- and post-dialogue briefings

In our experience, these costs usually total between $100,000 and $300,000 per session of dialogue. This compares favorably to the costs of supporting policy advocacy via research projects, roundtables, op-eds, and more, all of which seek to reach the very same people via more circuitous routes.

It also comes with a variety of risks, including the risk that an important issue comes to be viewed as merely a foreign idea, or even that a dialogue itself is seen as an influence operation. To avoid this misperception, funders will ideally come from uninterested neutral countries, and the dialogue will frame the issue not as “here is what you should do” but as “we think this problem is important; what do you think?” Coalitions of funders may also help to decrease fears of undue influence.[84]

This can be very public and very private:

Public readouts or “open letters” from eminent scientists

Private briefings for key decision-makers

Personal relationships —e.g., getting personal friends of the President to participate

Ideally, track 2 participants include former government officials, and at times even close friends of key decision-makers in current and former administrations. The best organizers of track 2 diplomacy score high on “convening power” — the ability to attract these kinds of people. As emphasized throughout this document, some “pure” track 2s (e.g. simply focused on cultural exchange) lack this feature.

Finally, dialogues can also force unilateral work on key issues, if the other side comes prepared with statements and reports. If state A’s experts keep showing up with lengthy research reports on AI misuse, and state B’s experts show up empty-handed, then state B’s experts may well start their own research projects on the issue, if only to avoid embarrassment at the next dialogue.

The Risk of Influence Campaigns and Intelligence Collection The ability for track 2 dialogues to raise issue salience is a double-edged sword. One important caveat to the value of beneficially shaping the views of key stakeholders is that transnational advocacy can be hijacked by state-backed influence campaigns. It is well-established, for example, that the KGB and the Stasi (via operation MARS and Friedenskampf, respectively) provided funding for and placed agents in so-called peace movements in the West in an attempt to advance the Soviet agenda, including via citizen diplomacy.[85] Track 2 organizers need to be aware of these risks, conduct rigorous due diligence on their funders, beware that their interlocutors are “collecting” information, and take measures (like pre- and post-dialogue briefings) to mitigate attempted disinformation.[86] Even the perception of such influence can decrease impact, as implied by the characterization of Pugwash officials by one Reagan administration official: “an unwitting tool of the Kremlin, if not worse.”[87] |

Establishing Backchannels for Crisis Communications

Crisis communication also has key functions in mitigating global catastrophic risks (see Call Me, Maybe? Hotlines and Global Catastrophic Risk for a more detailed discussion of the mechanisms). In a crisis, avoiding misunderstandings and increasing the flow of information can be critical for de-escalation. Some official channels exist for crisis communication, but backchannels can be equally important. Track 2 dialogues can increase the “surface area” for crisis communication in two ways:

Directly, via the dialogues — The dialogues themselves can be a forum for sharing important information during a crisis.

Indirectly, via dialogue participants — Dialogue participants can exchange emails and phone numbers and even develop friendships with their counterparts. During a crisis, these personal relationships can help leaders better understand a crisis and the possible ways to find a negotiated solution. This is related to the building of interpersonal trust outlined above.[88]

This may be especially important for the U.S.-China relationship, where military-to-military communications are “notoriously unreliable.”[89] The Biden administration has, since spring 2023, emphasized the importance of “open channels of communication across a full range of issues to reduce the risk of miscalculation,” but these official channels may close when they are needed most (e.g. during a period of heightened tensions).[90]

For example, if state A’s intelligence agencies noted that state B had amassed large amounts of computational resources and assessed that was about to run a major training run for transformative artificial intelligence, dialogue participants from state A could help to confirm or disconfirm this interpretation of the facts by contacting eminent AI scientists in state B. If these scientists suggested that the training run may be unsafe, then state A could use this information to raise the alarm internationally, potentially putting international and domestic pressure on state B and potentially delaying secretive and unsafe deployment. This may be accompanied by a demand for reassurances of safety and other confidence-building measures, or a “pause” to state B’s efforts to make time for international deliberation.

One example of track 2-mediated backchanneling and crisis communications occurred in the summer of 2020, when elements of the PLA apparently believed that a U.S. attack in the South China Sea was imminent as an “October surprise.” General Mark Milley reportedly had to call his Chinese counterpart and explain, “General Li, you and I have known each other for now five years. If we’re going to attack, I’m going to call you ahead of time. It’s not going to be a surprise.”[91] According to a former U.S. policymaker I interviewed who worked in the DoD at the time, China used track 2 dialogues as a channel to first raise these fears in 2020, which then made their way up to the DoD, where they reached U.S. leadership, which then used the Defense Telephone Link to defuse these fears. The person I spoke to explained, “They [Chinese officials] were so worried that they actually sent signals through some of our track 2 dialogues and track 1.5s with some U.S. institutions. And that filtered to us and it became so important that [DoD leadership] had to call their counterparts and say ‘the US is not going to attack you don’t worry.’” Thus track 2 dialogues served as a kind of crisis communications channel between the U.S. and China.

Implications

Why We Fund Track 2 Dialogues

Having outlined these theories of change, we can begin to see one reason to consider track 2 dialogues as potentially promising targets for philanthropic bets: they can be neglected levers on the priorities of multiple governments at once, especially if those governments have outsized resources and leverage. As is outlined in several Founders Pledge reports, policy advocacy can be a uniquely high-impact intervention, for several reasons:

“the vast scale difference between philanthropy and public spending (leverage), the necessity of policy change and its ability in triggering private action (causal primacy), and the abstractness and intangibility of advocacy that make it likely to be relatively underfunded.”[92]

This is especially true for issues related to foreign and security policy (major war, nuclear weapons, biosecurity, AI misuse, technology competition, etc.), because:

Foreign and security policy is the unique purview of governments. Classification, regulatory authority, prohibitive costs, and more all contribute to this dynamic.[93]

Defense budgets are vast. Even more than innovation spending and regulation (for climate change), defense and international affairs resources of major states are so large that

Philanthropic success stories like the grants that led to Nunn-Lugar and Cooperative Threat Reduction programs help to illustrate these dynamics.[94] But these advocacy efforts tend to be limited to the national level:

On some levels, therefore, track 2 dialogues are simply multi-pronged advocacy. As outlined above, several theories of change of dialogues directly influence government decision making, e.g. by:

Raising issue salience for key stakeholders — track 2s, especially with high-level participants (world-renowned scientists, former government officials, well-connected power brokers, etc.), can raise the salience of key risks (e.g. AI misuse) for government decision-makers, thereby affecting resource allocation.

Surfacing risk-reduction ideas — by object-level problem solving and exchanging information and ideas, track 2 dialogues can help policymakers expand their search for cooperative risk-reducing ideas on key issues.

Selecting these ideas for tractability — unlike national policy advocacy, track 2 dialogues already select ideas for tractability in the international arena; if the Chinese don’t like a proposal, they will make this clear (see e.g. the discussion on “trial balloons” in supporting track 1 diplomacy)

Crowding in government resources — e.g. by helping to launch track 1 diplomatic initiatives.

And more.

This multiplicative effect alone would be a reason to consider supporting track 2 dialogues, but:

Advocacy is otherwise not feasible in some countries. As described above, in some societies like the Chinese party-state, advocacy is simply not possible (or philanthropists may lack the expertise and risk-tolerance to support domestic PRC advocacy efforts).

Unilateral action is insufficient for many risks. Taking the example of pandemic prevention:

Pathogens don’t respect borders; a lab leak, deliberate release, or natural outbreak in one country can soon affect all countries. Global early detection is far more useful than mere national surveillance.

Bad actors don’t respect borders; if one country implements strict screening regulations for DNA synthesis, bad actors like terrorist groups can simply target providers of synthetic DNA in less-regulated countries.

Unilateral action may be net-negative. If one country’s defensive countermeasure stockpiling instills fears of offensive programs in another country, leading them to pursue an offensive program of their own, then unilateral action was plausibly worse than inaction.

This does not mean, however, that everyone needs to be at the table at a track 2 (indeed, this may stymie the likelihood of agreement). Rather, by inviting the most powerful states in the international systems, track 2 organizers can take advantage of the policy diffusion effects from these states.

(Similar dynamics are at play on the Chinese side, only with other actors, like Central Asian Countries, Belt and Road Initiative participants, Pakistan, Russia, DPRK, parts of the UN system, etc.)

Issue Area Choice Matters

In researching track 2 dialogues, I have occasionally heard the claim that it is the act of meeting and discussion between adversaries that matters much more than the content of those discussions; issue area choice is secondary to the fact of “exchange.” This is perhaps partly true for trust and confidence-building. For the other theories of change explored here, however, issue area choice matters, and the track 2 dialogue is more valuable when its topics are more important. Funding track 2 dialogues is therefore not a blind bet on the proposition that “intergroup contact is good.”

As a rough heuristic for comparing different dialogues, funders can use the same heuristics they would use to evaluate the content of the dialogues in other contexts. For funders concerned with extreme risks, therefore, it is important to fund dialogues focused specifically on these issues — biosecurity, risks from emerging technologies, nuclear war, etc. Similarly, funders concerned with security and safety will need to take heed to ensure that dialogues on emerging technologies are also focused on these issues.

Convening Power and Policy Transfer Matter

Additionally, several of the theories of change discussed here rely on the ability of the dialogue organizers to get the “right people” in the room, and to transfer ideas and insights to the policy ecosystem. This may lead funders to prefer organizers with pre-existing policy networks and a demonstrated track record of convening high-level meetings. High-level participants on one side are also likely to attract high-level participants on the other side, but conveners may need to exert more effort to understand the structure of e.g. the Chinese party-state and nodes of influence.[95] (The RAND report emphasized the importance of inviting participants of equivalent rank on each side.[96]) Evaluating the truth of claims to convening power will likely require extensive networking, checking with experts on the relevant policy communities, and the same “elusive craft” that is involved in evaluating policy advocacy.

Similarly, as emphasized throughout this document, funders need to evaluate funding opportunities for mechanisms of policy transfer, so that good ideas and information from track 2 dialogues actually reach relevant audiences on both sides. This is partly a function of inviting the right people, but it can also be aided by hosting policy briefings.[97] Funders should ensure that conveners have a plan for “policy transfer” (e.g. trips to D.C., “policy roundtables,” private briefings, etc.).

To convene members of certain communities, it may be necessary to pay for in-person convenings with certain perks: business-class or first-class flights, high-end hotels in faraway locations, honoraria, and other practices that may seem excessive to some funders concerned with cost-effectiveness.

Finally, as suggested above, bipartisan convening power may be especially valuable for the U.S. side of track 2 dialogues, to ensure continuity and hedge against political change.

“Track 1.5” is on a Spectrum

As noted in footnote 1, the term “track 1.5” sometimes refers to track 2 dialogues that have an element of official participation. The line between track 1.5 and track 2, however, is blurry; as noted above, many track 2 dialogues operate with the explicit understanding that both sides have instructions from their governments and will brief those governments, and official “observers” will sometimes join “pure” track 2 dialogues. In other words, many track 2 dialogues are de facto very similar to track 1.5 dialogues, and can be made more or less official depending on the topic and the political environment.

In general, because many of the theories of change stipulate at least some link to official channels (via briefings, via observers, etc.), we do not recommend funding track 2 dialogues that are completely disconnected from policymaking processes. For international object-level problem-solving alone, international scientific conferences and workshops may be more appropriate.

Dialogues are not Risk-Free

Finally, it is important to note that track 2 dialogues are not risk-free endeavors. Possible risks to each side include:

Intelligence collection — One person I interviewed told me that some dialogues are “stacked with collectors” from the Chinese Ministry of State Security and others.[98]

As noted above, however, this may actually be beneficial insofar as it facilitates the swift movement of ideas through the policy ecosystem.

Disinformation — As track 2 dialogues are channels for the flow of information, these channels can also be abused by actors seeking to spread false information.

This may, include, for example, the exaggeration of military capabilities, which may even worsen the very competitive dynamics that track 2 dialogues can alleviate.[99]

Other influence operations — See above; historically, some states have attempted to use track 2 dialogues to conduct influence operations on the peace movement.

Hampering official diplomacy — Conducted poorly, track 2 dialogues can short-circuit track 1 diplomacy and possibly be counterproductive.

However, often the upsides nonetheless appear to outweigh the downsides, and there are specific actions that dialogue conveners can take to minimize these downsides:

Briefing participants on the risks — Organizers can make it clear that some of their interlocutors during dialogues have multiple roles and may communicate all information to their respective governments.

Post-Dialogue “Hotwashing” — Organizers can debrief participants after discussions, explain best-practices about what to believe and not believe, and confer on possible false or exaggerated claims.

Keeping governments informed — To avoid short-circuiting track 1 diplomacy, organizers ought to keep relevant governments informed of their activities.

High epistemic standards — Funders can screen organizers for high epistemic standards and the ability to not fall for false or exaggerated claims.

Avoiding high-risk topics — Organizers can demarcate certain topics as “off-limits”, e.g. because they involve information hazards or might inadvertently transfer powerful capabilities.

Demanding evidence — When claims are made about specific capabilities or other facts about the world, organizers can demand evidence, or can note in policy briefings that certain claims were made without corroborating evidence.

Most of this can be done by the dialogue organizers alone. It is therefore important for funders to screen dialogue organizers for epistemic rigor, subject-matter expertise, and an understanding of informational hazards and the risk of dis- and misinformation. Moreover, it could be especially valuable to be able to triangulate between dialogues to see patterns, find multiple sources for valuable information, or discern attempts at coordinating influence campaigns across dialogues. Unfortunately, coordination between dialogues is currently ad-hoc and highly limited. In the future, I plan to write more about the potential upside of coordination mechanisms for dialogues focused on great powers and extreme risks.

Conclusion and Next Steps

This document outlines various theories of change for track 2 dialogue, but only partly validates these theories of change. Moreover, I have not attempted to rank them in order of importance, in part because I expect importance to vary by geography and issue area. There are many open questions:

Which theories of change are strongest for transformative technologies?

How do these theories of change vary with different countries (e.g. India-Pakistan dialogues vs. U.S.-China dialogues)?

How transferable is the experience of U.S.-Russia cooperation during the Cold War? What do the similarities and differences between CCP and Soviet political systems suggest about the tractability of track 2 dialogues in contemporary China?

How can funders make multi-year funding commitments while demanding accountability from grantees? How can such grant agreements be structured to be conditional on certain markers of success?

How many dialogues are enough? How many are too much? How does redundancy trade off against inefficiency?

and more…

I hope that this document can provide a base for evaluating these questions and diving deeper into the potential value of track 2 dialogues for mitigating global catastrophic risks.

About Founders Pledge

Founders Pledge is a global nonprofit empowering entrepreneurs to do the most good possible with their charitable giving. We equip members with everything needed to maximize their impact, from evidence-led research and advice on the world’s most pressing problems, to comprehensive infrastructure for global grant-making, alongside opportunities to learn and connect. To date, they have pledged over $10 billion to charity and donated more than $950 million. We’re grateful to be funded by our members and other generous donors. founderspledge.com

If you are interested in supporting track 2 diplomacy and other risk-mitigating efforts, consider donating to the Global Catastrophic Risks Fund.

- ^

“Track 2” diplomacy is often contrasted with “track 1” diplomacy, which is official government-to-government diplomacy. On the second track, non-governmental experts and retired government officials meet for “unofficial” or “backchannel” exchanges. The term “track 1.5” is sometimes used to refer to a variety of dialogues with a mixture of governmental and non-governmental participants. I generally do not find this term useful, however, because many dialogues that are technically “mere” track 2 are de facto track 1.5 because of participants’ close ties to their home governments (especially in dialogues with participants from the Chinese party-state, who are inevitably attending only with the permission of the CCP). Some of these grants were made directly, from the Founders Pledge Global Catastrophic Risks Fund; some were made via advising Founders Pledge members, with Founders Pledge as the legal donating entity; some were made via advising external philanthropists.

- ^

See, e.g. reports on great power conflict, strategic competition and transformative technologies, autonomous weapon systems and military AI, and more.

- ^

Stephen Clare, Great Power Conflict.

- ^

Peter Jones also outlines several theories of change in Track 2 Diplomacy: Theories and Practice (especially chapter 3), drawing on previous studies of track II diplomacy. Jones’s work, however, focuses largely on conflict resolution and management (e.g. finding common ground in long-standing ethnic disputes), and takes a practitioner’s perspective. In contrast, I take a funder’s perspective and focus on great powers and catastrophic risks, and outline a wider range of theories of change. Similarly, Rani Martin in “The Pugwash Conferences and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty as a case study of Track II diplomacy” outlines two theories of change: “new policy ideas” and “trust building,” corresponding to the first and second sections below.

- ^

Evangelista calls this “Provision of Information and Ideas” in Matthew Evangelista, Unarmed Forces: The Transnational Movement to End the Cold War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2002), 382.

- ^

For a more detailed discussion of the role of information asymmetries, see Stephen Clare and Christian Ruhl, “Great Power Competition and Transformative Technologies” (Founders Pledge and CIGI, 2024), https://www.founderspledge.com/research/great-power-competition-and-transformative-technologies-report.

- ^

John H. Herz, “Idealist Internationalism and the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 2, no. 2 (1950): 157–80, https://doi.org/10.2307/2009187; Charles L. Glaser, “The Security Dilemma Revisited,” World Politics 50, no. 1 (1997): 171–201.

- ^

Alibek, Biohazard: The Chilling True Story of the Largest Covert Biological Weapons Program in the World-Told from Inside by the Man Who Ran It, 235

- ^

This and related dilemmas are discussed in greater detail in Enemark’s Biosecurity Dilemmas.

- ^

- ^

Ibid., 7.

- ^

- ^

Missy Cummings has described one such dynamic on AI, writing that exaggerated claims “could then cause other countries to attempt to emulate potentially unachievable capabilities, at great effort and expense. Thus, the perception of AI prowess may be just as important as having such capabilities.” “The AI that Wasn’t There: Global Order and the (Mis)Perception of Powerful AI,” Texas National Security Review, https://tnsr.org/roundtable/policy-roundtable-artificial-intelligence-and-international-security/#essay2.

- ^

Amanda Kerrigan, Lydia Grek, and Michael Mazarr, The United States and China—Designing a Shared Future: The Potential for Track 2 Initiatives to Design an Agenda for Coexistence (RAND Corporation, 2023), 12, https://doi.org/10.7249/RRA2850-1.

- ^

This is evident in readouts from track II dialogues, where Chinese interlocutors sometimes appear to overestimate the power of the executive branch of the U.S. government in influencing the behavior of the other branches or the media.

- ^

On U.S.-China nuclear dialogues: “because China does not publish much nuclear information (and because there is no official strategic nuclear dialogue), the United States benefits greatly from engaging Chinese in Track-2 and Track-1.5 dialogues, even though they typically share much less than Americans, in part because they have a smaller arsenal and a policy based on strategic ambiguity.” David Santoro, “Track-2 and Track-1.5 US-China Strategic Nuclear Dialogues: Lessons Learned and the Way Forward” (Pacific Forum, 2022), https://cms.apln.network/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/David-Santoro-US-China-Strategic-Nuclear-Dialogues.pdf.

- ^

Matthew Evangelista, Unarmed Forces: The Transnational Movement to End the Cold War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2002), 19.

- ^

“When the opportunity arose, under Gorbachev, to debate competing proposals for Soviet security policy openly, the reformers continued to rely on their western colleagues for information and ideas.” Ibid., 382.

- ^

Greg Torode et al., “U.S. and China Hold First Informal Nuclear Talks in Five Years,” Reuters, June 21, 2024, sec. World, https://www.reuters.com/world/us-china-hold-first-informal-nuclear-talks-5-years-eyeing-taiwan-2024-06-21/.

- ^

Thanks to Sharon Weiner for this point in a round of external reviews.

- ^

For example, the atomic scientist Leo Szilard highlighted Pugwash’s “informal discussions,

in which a man would listen and then respond with a frown or a smile without having to say anything.” Paul Rubinson, “Pugwash Literature Review” (Urban Institute, 2019), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/100070/pugwash_literature_review_0.pdf.

- ^

“Both track 1.5 and track 2 dialogues are most successful when they have some connection to the formal policy process. To increase the utility of track 1.5 and track 2 dialogues, government participants should take what they have learned back to their respective agencies, and non-government participants should be encouraged to share their insights with government officials.” “A Primer on Multi-Track Diplomacy: How Does It Work?,” United States Institute of Peace, accessed April 18, 2024, https://www.usip.org/publications/2019/07/primer-multi-track-diplomacy-how-does-it-work.

- ^

- ^

Early in Pacific Forum dialogues, for example, “Rather than discussing ‘the issues,’ US and Chinese experts spent time going back to basics and defining key terms and concepts, creating common lexicons. The idea was that discussing the issues was pointless without a common, foundational strategic nuclear language.” David Santoro, “Track-2 and Track-1.5 US-China Strategic Nuclear Dialogues: Lessons Learned and the Way Forward” (Pacific Forum, 2022), https://cms.apln.network/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/David-Santoro-US-China-Strategic-Nuclear-Dialogues.pdf.

- ^

“One contribution to this development of public knowledge will be the rolling publication of a glossary of AI terms.” “Laying the Groundwork for US-China AI Dialogue,” Brookings, accessed April 23, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/laying-the-groundwork-for-us-china-ai-dialogue/.

- ^

Rani Martin also discusses building trust as a theory of change in https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/ggiCDnYcSKLxwFbBv/the-pugwash-conferences-and-the-anti-ballistic-missile#2_1_Theories_of_change.

- ^

Thanks to Rani Martin for this point in a round of external reviews.

- ^

There may be two separate but related kinds of trust at play here. One is trust in the accuracy of information provided, and the other is trust in the non-malicious intentions of the person providing the trust. Thanks to Oliver Guest for pointing to this distinction in a round of reviews.

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

John P. A. Ioannidis, “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False,” PLOS Medicine 2, no. 8 (August 30, 2005): e124, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. Kelsey Piper, “Science Has Been in a ‘Replication Crisis’ for a Decade. Have We Learned Anything?,” Vox, October 14, 2020, https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/21504366/science-replication-crisis-peer-review-statistics.

- ^

“[O]n the Chinese side, [initial exchanges] featured primarily pre-cooked talking points.” David Santoro, “Track-2 and Track-1.5 US-China Strategic Nuclear Dialogues: Lessons Learned and the Way Forward” (Pacific Forum, 2022), https://cms.apln.network/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/David-Santoro-US-China-Strategic-Nuclear-Dialogues.pdf.

- ^

It may seem puzzling that (1) everyone knows that information is reported back to governments, and (2) eavesdropping is a concern and participants need opportunities for confidential and frank exchange. I expect this is because official sessions are more visible, and can be easily monitored, and because participants may need to “tick the box” of having said their official position. Side conversations are more difficult to monitor, and information can be reported by participants selectively.

- ^

“[S]ome [dialogues] are more focused on relationship building while others take a problem-solving or outcome-driven approach, such as establishing a draft agreement, joint statement, or new proposal.” “A Primer on Multi-Track Diplomacy: How Does It Work?,” United States Institute of Peace, accessed April 18, 2024, https://www.usip.org/publications/2019/07/primer-multi-track-diplomacy-how-does-it-work.

- ^

The contents of CNAS’s report on Autonomy and International Stability are a good example of this, tracing how COLREGs and other agreements apply to the behavior of uncrewed and autonomous systems in the Indo-Pacific.

- ^

E.g. on U.S.-China nuclear dialogues, “for a long time, both sides centred the discussions mostly on explicating the US and Chinese positions on issues, much less so, if at all, on what should be done to reduce or eliminate the daylight between their respective positions” David Santoro, “Track-2 and Track-1.5 US-China Strategic Nuclear Dialogues: Lessons Learned and the Way Forward” (Pacific Forum, 2022), https://cms.apln.network/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/David-Santoro-US-China-Strategic-Nuclear-Dialogues.pdf.

- ^

Thanks to Tom Barnes for this point.

- ^

The following paragraph relies on the summary from page 4 of the Urban Institute’s literature review of Pugwash. Rani Martin also discusses the theory of “new policy ideas” through the lens of Pugwash in https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/ggiCDnYcSKLxwFbBv/the-pugwash-conferences-and-the-anti-ballistic-missile#2_1_Theories_of_change.

- ^

“In his letter supporting Pugwash’s nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize, Wiesner refers to

these discussions as ’very important to me in my efforts to achieve a nuclear test ban and reduce

sources of international friction.’ When the Soviets continued to balk at on-site inspections, Pugwash

scientists offered a technological solution to the problem. Glenn Seaborg, the head of the Atomic

Energy Commission during the 1960s and not himself a Pugwash scientist, credits the group’s idea of

using so-called black box seismic detectors in lieu of manned inspections as a breakthrough that showed the Soviet side ‘loosening’ its demands”. Paul Rubinson, “Pugwash Literature Review” (Urban Institute, 2019), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/100070/pugwash_literature_review_0.pdf.

- ^

- ^

- ^

See Jones’s discussion of Burton. Peter Jones, Track Two Diplomacy in Theory and Practice (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015), 138.

- ^

Amanda Kerrigan, Lydia Grek, and Michael Mazarr, The United States and China—Designing a Shared Future: The Potential for Track 2 Initiatives to Design an Agenda for Coexistence (RAND Corporation, 2023), 30, https://doi.org/10.7249/RRA2850-1.

- ^

Dalia Dassa Kaye, Talking with the Enemy, quoted in Amanda Kerrigan, Lydia Grek, and Michael Mazarr, The United States and China—Designing a Shared Future: The Potential for Track 2 Initiatives to Design an Agenda for Coexistence (RAND Corporation, 2023), 31, https://doi.org/10.7249/RRA2850-1.

- ^

“Regulators Need AI Expertise. They Can’t Afford It | WIRED,” accessed April 18, 2024, https://www.wired.com/story/regulators-need-ai-expertise-cant-afford-it/. See also Founders Pledge’s write-up on Horizon Institute for Public Service.

- ^

Thanks to Rani Martin for this point in a round of external reviews.

- ^

“Regulators Need AI Expertise. They Can’t Afford It | WIRED,” accessed April 18, 2024, https://www.wired.com/story/regulators-need-ai-expertise-cant-afford-it/.

- ^