Here is a conversation from the comments of my last post on the FDA with fellow progress blogger Alex Telford that follows a pattern common to many of my conversations about the FDA:

Alex: Most drugs that go into clinical trials (90%) are less effective or safe than existing options. If you release everything onto the market you’ll get many times more drugs that are net toxic (biologically or financially) than the good drugs you’d get faster. You will almost surely do net harm.

Max: Companies don’t want to release products that are worse than their competitors.

Companies test lots of cars or computers or ovens which are less effective or safe than existing options but they only release the ones that are competitive. This isn’t because most consumers could tell whether their car was less efficient or that their computer is less secure, and it’s not because making a less efficient car or less secure computer is against the law.

Pharmaceutical companies won’t go and release hundreds of dud or dangerous drugs just because they can. That would ruin their brand and shut down their business. They have to sell products that people want.

Alex: Consumer products like ovens and cars aren’t comparable to drugs. The former are engineered products that can be tested according to defined performance and safety standards before they are sold to the public. The characteristics of drugs are more discovered than engineered. You can’t determine their performance characteristics in a lab, they can only be determined through human testing (currently).

Alex claims that without the FDA, pharmaceutical companies would release lots of bunk drugs. I respond that we don’t see this behavior in other markets. Car companies or computer manufacturers could release cheaply made, low quality products for high prices and consumers might have a tough time noticing the difference for a while. But they don’t do this, they always try to release high quality products at competitive prices.

Alex responds, fairly, that car or computer markets aren’t comparable to drug markets. Pharmaceuticals have stickier information problems. They are difficult for consumers to evaluate and, as Alex points out, usually require human testing.

This is usually where the conversation ends. I think that consumer product markets are informative for what free-market pharmaceuticals would look like, Alex (and lots of other reasonable people) don’t and it is difficult to convince each other otherwise.

But there’s a much better non-FDA counterfactual for pharmaceutical markets than consumer tech: surgery.

The FDA does not have jurisdiction over surgical practice and there is no other similar legal requirement for safety or efficacy testing of new surgical procedures. The FDA does regulate medical devices like the da Vinci surgical robot but once they are approved surgeons can use them in new ways without consulting the FDA or any other government authority.

In addition to this lack of regulation, surgery is beset with even thornier information problems than pharmaceuticals. Evaluating the quality of surgery as a customer is difficult. You’re literally unconscious as they provide the service and retrospective observation of quality is usually not possible for a layman. Assessing quality is difficult even for a regulator, however. So much of surgery hinges on the skill of a particular surgeon and varies within surgeons day to day or before and after lunch.

Running an RCT on a surgical technique is therefore difficult. Standardizing treatment as much as in pharmaceutical trials is basically impossible. It also isn’t clear what a surgical placebo should be. Do just put them under anesthetic for a few hours? Or do you cut people open and stitch them up without doing anything else? So surgical RCTs are rare and small when they happen.

Despite extreme information problems and a complete absence of federal oversight, surgery seems to work well. Compared to similar patients on the waiting list, 2.3 million life years were saved by organ transplants over 25 years. The WHO claims that “surgical interventions account for 13% of the world’s total disability-adjusted life years.” Coronary artery surgery extends lifespan by several years for $2300 a year. Cataract surgery and LASIK can massively improve quality of life for a few thousand dollars.

Surgery is also improving over time. Pancreaticoduodenectomy, the surgical treatment for pancreatic cancer, began in the late 19th century as a near death sentence, although to be fair so was pancreatic cancer. For several decades surgeons were unsure whether it was even possible to survive anything except partial versions of the procedure. They experimented on dogs, cadavers, and consenting terminal patients and improved the procedure. Today, the procedure is safe and a standard treatment for pancreatic cancer. From 2006-2012 the mortality rate halved from 2.9% to 1.5%.

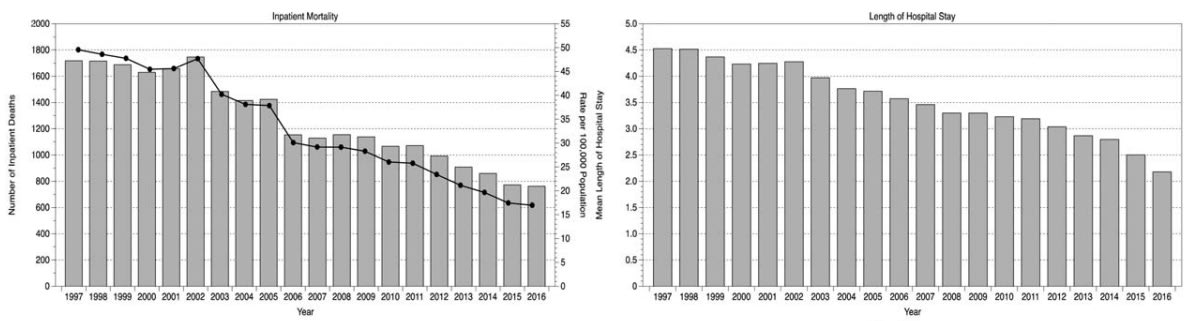

On a larger scale, among all emergency general surgery episodes in Scotland from 1997 to 2016, inpatient mortality mortality rates declined by more than three times and hospital stay lengths were cut in half, probably due to the rise of minimally invasive and robotic surgery tools.

In the US, the death rate from medical and surgical care complications declined by 39% from 1999 to 2009.

Operative mortality for eight different cancer and cardiovascular operations from 1999 through 2008 declined with the lowest decline being 8% and the highest at 36%.

These are common surgeries with hundreds of thousands of operations each year.

There are problems with surgery. There are unnecessary deaths and ineffective procedures. There are bad actors and high prices. But surgery is not the vision of snake oil and certain death that is painted by many FDA defenders when you ask them to imagine a world without the FDA. The problems faced by surgery are matched and sometimes exceeded by problems faced by pharmaceuticals.

There are also non-governmental mechanism which constrain surgeons and protect consumers. Competition, insurance companies, hospital lawyers and ethics boards. But this strengthens the point. An FDA model is not the only way to promote consumer protection and solve the information problems presented by medicine and surgery.

So we don’t need to argue about the validity of consumer tech or cars as a non-FDA counterfactual for pharmaceuticals. Surgery has at least all of the market challenges that harry pharmaceuticals and it doesn’t have an FDA. Yet, it still muddles through. This is what we should expect pharmaceuticals to look like if we abolished the FDA. We would have a well-functioning, self-improving market for medical treatments without billion-dollar fifteen-year waits for any new drug that people want to try.

I think the FDA and other regulatory bodies are critically important, market economies don’t work well for medicine and that surgery is not a great comparator. Here are some scattered thoughts

Surgery outcomes generally have short feedback loops. With medication, it can take years to understand potential harms, with surgery you usually know quickly whether outcomes are good or bad. The classic example of unexpected harms with a long feedback loop is Thalidomide, which caused severe birth defects in tens of thousands of babies. Regulation tightened up after this and we haven’t had a similar scale problem since

The medical field is built on trust. The general public expect that there has been a hypervigilant, rigorous process that ensures they are very likely to gain benefit from medication, but more importantly that the chance of catastrophic negative results is as close to zero as possible. This ensures we get vaccinated, go to doctors and take medication which increases the quality of our lives.

The second order and potentially catastrophic negative effects to harm-causing medications slipping through less regulation could also be immense. I think if a similar issue to thalidomide happened now, there could be a wholescale breakdown of trust in the medical field in general which could lead to delays in seeking medical care, drops in vaccine rates around the world and increase in predatory non evidence-based predatory medical providers.

I won’t get into the weeds of why treating medicine as a regular commodity in the market can lead to disaster, but the obvious example is the opioid crisis in the U.S.A. The market-friendly policies allowed heavy marketing of opioid medication both to patients and doctors (most countries in the world don’t allow this) which, along with poor regulation of doctor prescription practises (and a bunch of other reasons) contributed to the U.S.A being one of the first high income countries in the world to have a reduction in life expectancy.

Sure there might be some people (like you) that are willing to take higher risks with medication to perhaps get higher rewards, but I don’t think its a good idea to design our system around a minority of people who are willing to ride the lightening, when most people want a close to failsafe system with far less risk and less reward.

These are just a few thoughts, there are other important functions like good oversight of clinical trials and monitoring of side effects which I won’t weigh into here. I don’t know much about the FDA in its current form, and I’m sure there’s plenty of room for improvement, but the potential downsides of doing away with medical regulators seem to outweigh the potential benefits of faster and cheaper medication.

Any reason why anyone would compare the effectiveness of the regulated drug market with something which is very unlike the drug market (the high-cost-of-delivery litigation-magnet that is surgery) and not something which is very similar to an unregulated version of the drug market like, say, the supplement or alternative medicine industry?

DALYs are bad. Averting them is good.[1] This means that 13% of the world’s loss of healthy life years is caused by the outcomes of surgery interventions. This is probably better than the counterfactual (no surgery), but it’s kind of a weird metric to cite when defending the safety of surgery?

Ironically, we often use DALYs to mean “averted DALYs”, especially in EA. This annoys me.

Yes to that footnote but the original abbreviation is confusing. It should be something like “disease adjustments to life years” .. not “disease adjusted life years”. Bc life years are good in general.

Thanks for sharing your post!

I briefly skimmed through the wikipedia list of withdrawn drugs. I looked at those withdrawn in the US or worldwide since 2007 (only eleven).

As far as I could tell (and I easily could have missed something) none of the associated pharma companies seem to have been financially ruined. The only ones who no longer existed (Wyeth and Celltech) were bought out by other pharma companies for princely sums (Wyeth by Pfizer for $68billion and Celltech by UCB for £1.5billion) before the recalls happened.

I guess doesn’t seem clear to me that pharma companies face threatening risks of ruining their brands and shutting down their business if they produce more inefficient or even more dangerous drugs than already. Even thalidomide didn’t destroy its parent company (Grünenthal).

I’m sure someone who knows more can correct me, but the only example of this happening in recent times Purdue Pharma.