Critique of OpenPhil’s macroeconomic policy advocacy

Summary

Recently, some defended OpenPhil-funded advocacy for looser (i.e. more expansive) macroeconomic policy (i.e. both fiscal and monetary policy). This is because in the 2010s, and also after covid, looser policy and higher inflation were better than lost growth and unemployment.[1]

While this might be true, here I argue that OpenPhil grants in ’21 caused looser macroeconomic policy, which contributed to overshooting on inflation.

My model is based on the following claims:

Short-term inflation is too high, volatile, and dispersed

Inflation (volatility) is high in poorer countries

Real wages are down

Inflation causes populism

Looser policy is a major cause of inflation

OpenPhil’s advocacy caused looser policy

Strong claim: Risk could have been predicted before the event and loose policy was a mistake ex-ante

Weak claim: Risk was hard to predict and was only a mistake ex-post

To be clear, I’m not arguing that inflation is always worse than unemployment and my ambition here is not to evaluate the program’s overall impact. Rather, I single out grants made in ’21, which caused looser policy and might have caused harm on the ‘21 margin. In other words, given diminishing returns to looser policy in ’21, the marginal benefits of looser policy was low as it didn’t add many jobs. However, inflation had high costs—on the ’21 margin—such as adverse effects in developing countries, reduction of real wages for some populations, which might increase populism and make the US Democrats lose upcoming elections.

Concretely, in order of strength, I provide evidence for the following claims on the adverse effects of looser macroeconomic policy:

Very strong claim: The first-order effects of too loose policy on the ’21 margin were unequivocally bad and will leave most worse off, even the poor, because we way overshot on inflation. Policy in ’21 added few jobs and real wages are down even for the poor (who suffer the most when their real wages go down even by a little). The second-order effects are that Dems will lose House, Senate, and Presidency. Populists (like Trump) will be elected, whose incompetence will make things even worse. The effects of looser policy in richer countries spill over into poorer countries, where inflation is higher, more persistent (hyperinflation), which leads to less growth, wellbeing, populism and instability.

Medium strength claim: Looser policy on the ’21 margin was good for the poorest 10% Americans (~30m) as it created more jobs and higher wages, but bad for the middle class (~150m) as their real wages went down. The first-order effects for wellbeing are still positive on average, as the poorest benefit much more than the middle class lost (a simple rule of thumb is that $1 is worth 1/X times as much if you are X times richer and poorest Americans are more than 5x poorer [utility is logarithmic in consumption]). However, because 150m have lost in terms real income, which can predict midterms and naïve extrapolation of current income decline predict Dems losing 50+ seats, the resulting populist incompetence will have, at the very least, high downside risks (like Trumpists starting trade wars). This will harm everyone (in expectation), even the poorest, in the longer-run.

Weak claim: Looser policy, even on the ’21 margin, was good for all Americans as it created jobs, increased real wages for most Americans (at least over the medium run) and led to GDP growth in the US and even for the world economy. However, even if real wages increased and inflation is transitory and mild over the medium-run, because voters are too sensitive to high short-term inflation, and inflation coincides with the midterms, and think it’s more persistent than the market, Dems will lose at least the House. Renewed gridlock and polarization will have bad effects and we could have avoided this by moving more slowly to a higher inflation target and being more expansionary under the curve in the longer-term.

I also highlight some general issues with macroeconomic advocacy like reducing central bank independence, problems with lobbying foreign central banks, and having to be very careful and do a lot of analysis before making grants that might have a lot of leverage and are not robustly good (like improving health).

The EA community promotes OpenPhil’s work and funges with their grants,[2] and so it’s important to figure out whether we’re value-aligned.[3] This is also an example of red teaming.

Thanks to Joel Becker, Remmelt Ellen, Fin Moorhouse, Peter McCluskey, Michael Dickens, Glen Weyl, Tyler Cowen, Rob Wiblin, Michael Townsend, Ben Edelman, Andreas Prenner, and Kevin Kuruc for feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript. Errors and opinions are mine.

Short-term inflation is too high, volatile, and dispersed

While average long-term inflation is not too high, it is too high in the short-term. This high inflation volatility and dispersion are causing instability and harm. Even if longer-term inflation is too low, the current spike in inflation is not an effective way of remedying it.

There is no consensus on how high inflation should be. [4] But few economists argue that inflation should be >4%, and many say that the European Central Bank (ECB) should target 2%.[5]

Yet, the IMF forecasted ~4% inflation in rich countries and ~6% in poorer countries for 2022 before the war.[6]

EU inflation hit 6.2% in Feb ’22.[7] The ECB projects 3.5% in 2022, 1.7% in 2023.[8] In some countries inflation is higher: ~12% in Estonia and Lithuania, 8.5% in Belgium and Slovakia.[9] Eurozone inflation dispersion is normally at 1 SD, now it’s at 2.7 SD.[10] Such excessive inflation dispersion can be problematic because countries cannot adjust their exchange rate.

US inflation hit 7.9% in Jan ’22.[11] In some small towns in the Midwest and South, inflation is 9% or more.[12] Even if one excludes more volatile prices from inflation like food and energy, inflation, right now, is too high.[13] However, the median prediction of inflation for 2022 by economists is 3.5%.[14]

Markets predict inflation to go down in the next few years: In the US, average inflation is forecast to stay high at an average of 3.5% over the next 5 years, but then go down to an average of 2.3% from 2027-2032 (2% for the EU[15]) and so average 3% over the next 10 years.[16] And so, markets do not predict a higher inflation target, but stick to the 2% target.[17] Similarly, experts forecast 2.3% over the next 10 years.[18]

Inflation (volatility) is high in poorer countries

Inflation is increasingly synchronized globally[19] and ECB and the US Federal Reserve (Fed) monetary policy shocks affect poorer countries.[20] This adds ‘fuel to the fire’ to already high inflation in poorer countries (pre-war inflation estimates: Russia ~9%[21], Pakistan 13%, Nigeria 16%, Ethiopia ~35%, and Turkey ~55%[22]).[23] Globally, food prices are very high.[24] Local monetary policy in poorer countries might not offset large spillovers from Fed (or ECB) policy shocks.[25]

Rising US interest rates are bad for poorer countries as they

“increase debt burdens, trigger capital outflows, and generally cause a tightening of financial conditions that can lead to financial crises [Especially] if higher rates are driven mainly by worries about inflation or a hawkish turn in Fed policy, which we jointly describe as monetary news, this will likely be more disruptive for emerging markets.”[26]

If rates rise, investors find the US more lucrative and pull capital from poorer countries. Often, these abrupt outflows (‘sudden stops’), cause economic harm and widespread increases in poverty in these countries. And so changing the level of US hawkishness might not change this, but long-run changes in Fed policy might, as outflows are cyclical (c.f. Global Financial cycle). The global labor market has not recovered from the pandemic and tightening in advanced economies might prevent recovery in poorer countries.[27] From a global humanitarian perspective, these effects might dominate suboptimal macro policy hurting rich countries. However, long-term, growth and also political stability in rich countries is very important for global growth and development.[28], [29] This seems like a crucial consideration. In other words, policy in advanced economies should probably do what’s robustly good for their own economies.

Even if, generally, longer-term inflation is too low, we should increase the inflation target smoothly. Excessive inflation volatility[30] and dispersion[31] creates economic uncertainty.

In March ’22, a survey asked top economists if the fallout from the invasion of Ukraine will be stagflationary in that it will noticeably reduce global growth and raise global inflation over the next year. 26% strongly agreed, 53% agreed, 21% were uncertain, and no one disagreed.

Lower and more stable inflation is often associated with better growth and development, partly by reducing uncertainty, more efficient allocation of resources, and preserving financial stability.[32]

Real wages are down

Of course, wages and employment are up. Generally, while poorer people are affected more by inflation (e.g. as they spend a larger share of their money on gas and food),[33] their wages have also gone up more since covid.[34] As a rule, poorer areas have higher wage[35] and employment growth.[36] However, low-skill wages grow less than average[37],[38].

‘Last year, the US economy grew 5.7%, the largest annual increase since 1984. Unemployment plummeted. Workers, and especially low-income workers, saw massive wage gains. New businesses formed at record rates. Poverty fell below pre-pandemic levels. It’s wild. Savings skyrocketed. Bankruptcies are way down. This is great news and not expected, not inevitable and definitely not to be taken for granted politically or economically.’[39]

But while nominal wages have also increased, real (inflation-adjusted) wages have decreased on average.[40],[41] For instance, while median hourly wages have gone up by 4% over the year, older people’s wages are stickier and have only gone up by 2.5%.[42] 150m Americans now make less than last year—the biggest decline in their lifetime.[43]

If more jobs cause steady and predictable inflation, it can raise real wages, whereas large and unexpected inflation can lower them—as is happening now.[44]

The poor have fewer hedges against inflation, like real estate (and also crypto), but rather assets and liabilities, like cash or rent, worsened by inflation.[45] People with fixed interest rate loans from mortgages, cars, or student loans benefit from inflation are often richer over their life course. To quote Cowen: ‘the effects of inflation are numerous and complex. It cannot be said definitively that inflation hurts some income groups more than others. Yet it’s clear that, for the poor, inflation is no trivial matter.’ For instance, inflation has been called ‘a regressive consumption tax’.[46]

Inflation causes populism

More voters have seen their real wages go down than up (mostly in the lower income brackets). And so, even if inflation increases total welfare as the poorest 10% gain more from having a bit more money than everyone else loses from having a little less—this might then still increase populism. 150m Americans now make less than last year—the biggest decline in their lifetime.[47]

The impact of inflation on politics is clearer than its impact on the economy.[48] This might help populist Republicans:

‘Even if the economists who think inflation will decline this year turn out to be right, the effect on working-class voters may be disastrous for Democrats in the midterms.’

The GOP sees inflation as a winning issue[49] and it might have led to a surprise win of a Republican becoming Governor (exit polls show economy was the main issue). For instance, the Republican party head tweeted ‘inflation is hammering working families from coast to coast but Democrats want to print, borrow and spend trillions more.’ [50]

Americans expect inflation to persist over the next six months.[51] Laypeople think inflation will be higher next year (4.7%) than experts (3.7%) and also longer-term.[52] 54% of Americans see inflation as the best economic indicator, only 19% think it’s unemployment.[53]

Laypeople also blame the government more for inflation than experts.[54] 69% of Americans disapprove of how Biden is handling inflation, with only a slim majority (54%) of Democrats approving.[55]

‘Rocky ratings for Biden at a time when the bulk of Americans name inflation and pain everyday bills as top concern. Concern about inflation has eclipsed by worry about the pandemic’.

One economist says the bigger question is whether inflation will have a big bearing on the midterms, which ‘typically go to the other party and it just seems that this inflation surge has become such an issue that it’s just going to add more weight to that. And maybe the Republicans take back the house, maybe even in the Senate.’[56]

Indeed, betting markets predict

only a ~45% of Democrats winning the presidency in 2024[57]

only a ~23% and ~17% chance Democrats won’t lose control of the Senate[58], and House respectively.[59],[60]

~10% they’ll keep both House and Senate.[61]

Real income can predict midterms and naïve extrapolation of current income decline predict Democrats losing 50+ seats. [62],[63] OpenPhil is funded by one of the biggest democratic donors,[64] so these developments aren’t in their self-interest.

In the EU too, looser policy might cause a populist surge.[65] Inflation is a big issue for voters and might influence French elections.[66]

As a rule, tighter monetary policy can lower chances for conservatives (which are currently populist). This is because, if inflation is low, their comparative advantage in ‘fighting inflation’ disappears. In the UK, if the interest rate goes up by 1pp before elections, conservatives’ popularity goes down by ~0.75pp.[67]

Generally,

‘banking, currency, inflation, or debt crises lead to greater ideological polarization in society, greater fractionalization of the legislative body, and a decrease in the size of the working majority of the ruling coalition. The size of the governing coalition shrinks after almost any type of crisis (banking, currency, or inflation crises) and, at the same time, political fragmentation increases.’[68]

More political instability and social polarization, less democracy, and lower de facto central bank independence are associated with more volatile inflation.[69]

‘Inflation shocks’ are similar to the ‘China shock’ literature[70], where abruptly liberalizing trade or migration, though increasing welfare on average by lowering prices, can hurt the poorest in rich countries:

In the US, in counties with more import competition from China, people watched more FOX News, campaign contributions became more polarized, voted more Republican, and may have helped Trump win.[71]

In the UK, Brexit votes were also caused by import competition from China,[72] exposure to EU immigration and trade,[73] and low education, income, and high unemployment (because of overdependence on manufacturing).

Similarly, even if inflation increases average well-being,[74] ‘inflation shocks’ might be bad for some groups. While inflation’s impact across income distribution is broader than that of trade, we still might hurt poorer places (e.g. the Midwest in the US or Lithuania in the EU) that now have ~10% inflation, or groups with stickier wages like low-skilled workers or 55-year-olds, hiding in averages. Even if, in contrast to the trade reform, macroeconomic reforms might help the poorest, and so increase welfare on net, ‘shocks’ to the middle class can cause populist backlash (150m Americans have significantly lower real wages than a year ago).

It’s not that we should have less trade, migration or a higher inflation target: but reforms should be phased in slowly—we can still liberalize more or target higher inflation under the curve.[75]

Looser policy is a major cause of inflation

Generally, looser macroeconomic policy causes inflation.[76]

While supply-side factors are a major cause of inflation, demand-side factors like loose macroeconomic policy (e.g. monetary policy like low interest rates and quantitative easing and fiscal factors like a large stimulus) are as important according to surveys of macroeconomists.[77],[78] Another Jan ’22 survey of economists showed that few economists agreed that ‘Global supply chain disruptions are the main driver of elevated US inflation over the past year’.[79] Supply increased in ’21—and so current inflation is more of a demand than a supply shock.[80]

Many economists agree that the current combination of US fiscal and monetary policy are a serious risk of prolonged higher inflation.[81] Even historically dovish Krugman agrees with Summers:

‘Where we are today can be attributed to both monetary and fiscal policy, either could have led to the situation being avoided.’ They agree that we need to tighten now.[82]

Even the Blackrock CEO, who emphasizes supply-side reasons, concedes

‘central banks should take their foot off the gas this year by removing the extremely accommodating stance of monetary policy and return rates to a more neutral setting.’[83]

Another economist says:

“In response to the 2020 pandemic-induced recession, the Fed quickly adopted an ultra-loose policy stance, dropping short-term interest rates to zero and buying bonds to pull down long-term rates. In retrospect, it should have begun returning to a more neutral policy stance after the passage of the American Rescue Plan, in March 2021. But neither the Fed nor most private forecasters began to predict an overheating economy until much later in the year.”[84]

One economist notes:

‘We have no recent experience in an environment with unanchored inflation expectations’. Another economist comments: ‘Source of inflation is uncertain but the current policy mix seems to assume too low probability that monetary/fiscal policy can make it worse.’[85]

One top economist said:

‘A lot of different people and groups started assuming looser policy is always better, that was a big mistake’ [...] ‘Most Western countries have lower rates of inflation [~3%] than [the US, which has 7.5%], but still have higher inflation [because they started from a historically low baseline]. That may be unavoidable. The real culprit, in my view, was the extra $2 trillion of stimulus done by the Biden administration. Without that, I think we would be at Western European rates of price inflation. Given that spending, the Fed had no political choice but to accommodate. Most of what we did was correct, and then we made one big mistake.’[86]

The money supply (M4) grew by 30% in the year to July 2020, ~3x as fast as in any similar period since 1967.[87] The Fed’s balance sheet went from $4T in Jan ’20 to $9T now.

Driving metaphor: Since we were ‘asleep at the wheel’, central banks now have to do more than ‘take their foot off the gas’ or even ‘tap on the brakes’ (raise interest rates slowly and gradually). Instead, they now have to ‘hit the brakes hard’ (raise interest rates abruptly and repeatedly). This might cause a ‘hard, not a soft landing’ (raising interest rates just enough to curb inflation and stop the economy from overheating, without causing a significant increase in unemployment). Blaming current inflation on supply chain bottlenecks is like blaming car crashes on whatever object the car slammed into.[88]

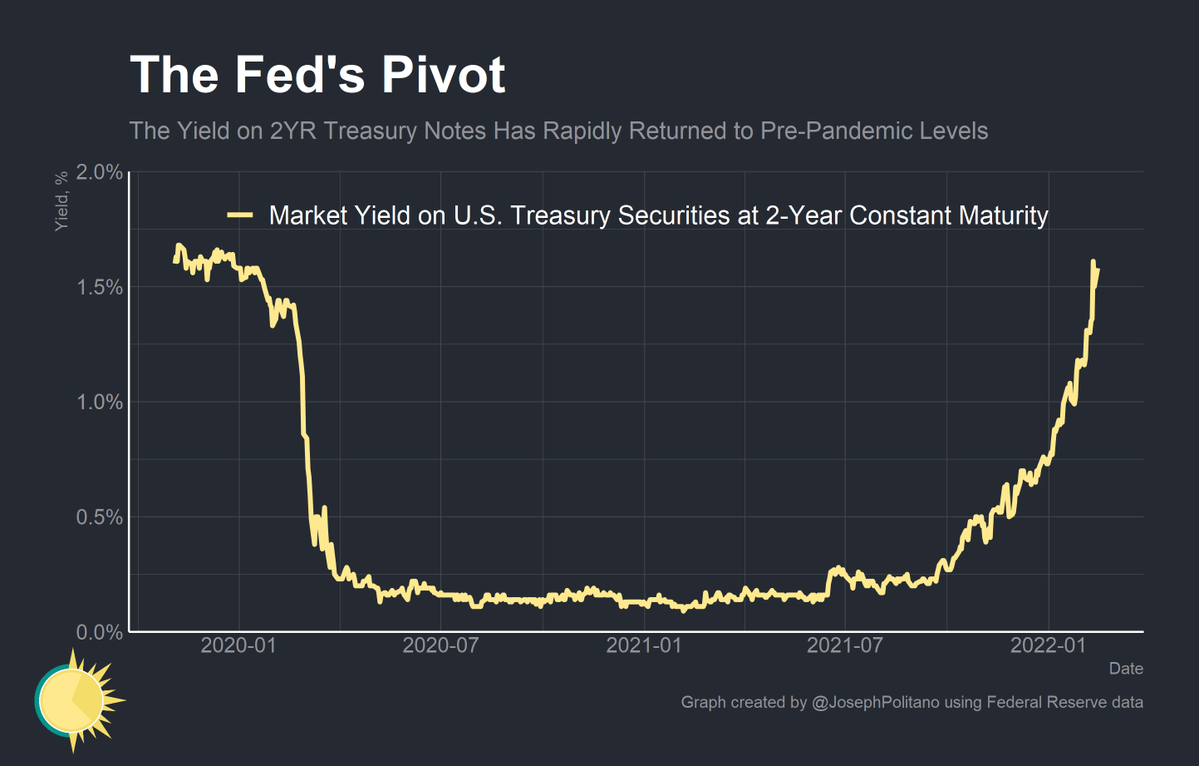

Indeed, the market predicts that[89] Fed and ECB will pivot and tighten now[90]—probably drastically.[91] The Fed policy reversal will be extremely rapid and strong, with markets rates will rise by 1.5% in the next year:[92]

41% of top economists surveyed say that the Fed response is “Too little, too late and insufficient to help keep inflation under control”:[93]

But to lower inflation by 2pp now, requires about a 4-5pp rate hike, which will take over a year.[94]

In essence, looser policy might have helped in the 2010s and post-covid. But we overshot and should have started tightening earlier.

Some disagree:

One economist says the Fed shouldn’t have tightened earlier (7:30mins in)

In Nov ’21, another economist similarly said ‘The Fed erred correctly on the side of labor market recovery over inflation risk. Inflation risk is now inflation reality. Recalculating…’ [95]

A macroeconomist at Brookings said ‘Hindsight is 20⁄20’ but believes the policy was necessary for an even recovery. The co-founder of the left-leaning Center for Economic and Policy Research, agrees. To build an even recovery across the country, that aid was necessary.’[96]

In March ’21, another economist argues that the Fed should not have taken its feet off the gas a year or so ago and that facing the current new supply shocks of Ukraine and China’s zero covid policy from a lower current inflation rate would have a small advantage. Rather, this supply shock will hit an economy with well-anchored inflation expectations, and 4% rather than at 7% over the past year is vastly outweighed by the costs of having 3m more jobs.[97]

The central bank can only curb inflation by slowing down the labor market.[98]

But I’m skeptical. According to Furman—Obama’s former economic advisor:

‘Blaming inflation on supply lines is like complaining about your sweater keeping you too warm after you’ve added several logs to the fireplace.’[99] [...] ‘There’s a difference between heating the economy one log at a time and throwing all the logs on the fire at the same time,’ [...] Everyone agreed that the economy needed fiscal support. But [...] a bit of tell — that no one has criticized it for being too small, in retrospect.’[100]

This argument implies there was a status quo bias as evidenced by the ‘Reversal Test’:

Reversal test: ‘When a proposal to change a certain parameter is thought to have bad overall consequences [in retrospect], consider a change to the same parameter in the opposite direction. If this is also thought to have bad overall consequences, then the onus is on those who reach these conclusions to explain why our position cannot be improved through changes to this parameter. If they are unable to do so, then we have reason to suspect that they suffer from status quo bias.’[101]

Here, the parameter is how loose or expansionary macroeconomic policy was. It was was unlikely to be precisely optimal in terms of its looseness in ’21. If you disagree that policy was not too loose in ’21 even in retrospect, and we made a mistake, then you must agree that policy should have been even more expansionary then to be consistent—that we should have had an even bigger stimulus, even lower interest rates and even more QE—or you’re likely to be biased towards the status quo.

‘Wise owls were dovish in the 2010s and are hawkish today. Don’t be a permahawk or a permadove.’[102]

To paraphrase Furman:[103] Both the position that loose policy created lots of jobs, income, and growth, but not much inflation, nor the converse position that loose policy caused lots of inflation but little growth are wrong. Rather, we got more and more inflation and fewer and fewer jobs for each dollar we added. The first $1T of stimulus led to a great recovery, but the last $0.5T of stimulus caused a lot of inflation but only few jobs. In other words, the marginal cost-effectiveness of looser policy was bad and the stimulus should have been smaller—maybe $1 trillion instead of 2.

Indeed, empirically we now see that the US labor market is now very tight,[104] i.e., close to full employment[105] and hasn’t added many jobs recently.[106],[107] This is another sign that we’ve hit diminishing returns to expansionary (looser) policy.

OpenPhil’s advocacy caused looser policy

OpenPhil’s macroeconomic stabilization program has funded think tanks to advocate for looser fiscal and monetary macroeconomic policy since 2014.[108]

They argue that the Fed (monetary policy) and US policymakers (fiscal policy) moved in their direction and ‘adopted a lot of more expansionary policies and became more focused on increasing employment, relative to worrying about inflation.’ OpenPhil’s CEO says they ‘might’ve played a small role in that, and the stakes I think are quite high in terms of human wellbeing there. So I see that as a big win.’[109]

It can both be true that the overall impact of OpenPhil’s macroeconomic stabilization program might be positive and the later parts negative. Many agree with OpenPhil that policy was too tight after ’08,[110] and that looser policy after covid led to a better recovery. Similar to the discussion above, perhaps a looser environment with more jobs led to less populism. But my ambition here was not to evaluate the program’s all things considered impact, but to single out the ’21 grants which might be harmful, which is still useful.

Some argue that generally, advocacy like the OpenPhil-funded FedUp doesn’t have a strong counterfactual impact.[111] Either way, either the advocacy caused inflation and created harm or it was ineffective and the grants weren’t a big win. It’s hard to estimate the effect size of these grants: it’s not that they caused the stimulus or led QE to be large, but rather they helped create an environment that was more dovish on inflation by funding (relatively non-academic) think tank advocacy.

In mid-’21, OpenPhil funded both orgs in the US[112] and EU[113] who advocate for looser policy. These organizations have very recently emphasized supply-side factors as a cause of inflation (e.g. covid disrupted the supply chain and increased demand for goods, the Ukraine conflict caused energy prices to go up). At the same time, they downplayed demand-side factors (e.g. loose monetary and fiscal policy). They argued against tightening until very recently.[114]

Strong claim: Risk could have been predicted before the event and loose policy was a mistake ex-ante

In May ’21 already, the market predicted ~2.7% average inflation in the US over the next 5 years.[115] This is over the 2% target (though this is PCE instead of CPI inflation, which can be higher[116], and also these measures might not be perfect, see[117],[118]). Yet, as late as mid-’21, OpenPhil was still funding advocacy for looser policy in the US[119] and EU[120]—and the funded org’s advocacy continued until early February.[121] This is despite inflation being so volatile and labor markets being very tight. Even if we should target higher inflation longer-term,[122] in mid-’21, markets already predicted that we’d go back to the ~2% target eventually—and so these grants just caused even more short-inflation volatility.[123]

Still, some predicted these risks and warned of such loose policy. For instance, in Feb ’21 one top economist provided a back-on-the-envelope calculation that the stimulus was way too large: assuming a multiplier of 1.2, the added demand of $2.8T, 3x estimate of the output gap.[124] Former Fed-chair Summers warned of inflation in May ‘21.[125] An econometrics paper from May ’21, estimated a 32% chance of >6% inflation in 2022 and warned that the discussion was based on casual observation rather than econometrics.[126]

In July ’21, OpenPhil’s CEO seemed uncertain in an interview:

’Host: ‘In the EU, it doesn’t seem like people have learned the lesson from 2008 [that not enough stimulus can hurt economic recovery] all that much. It seems like the EU would basically go and do exactly the same thing again. Which is strange.’

Alexander Berger: I agree. It’s strange’.

It is true that before covid, most economists agreed that the Eurozone would be in better shape if fiscal policy were more expansionary (which would allow monetary policy to be slightly less so).[127] But on the fiscal side, many economists surveyed in July ’19 agreed that there was little that the ECB could do to increase or maintain output (as they were already at the zero lower bound).[128]

Also, recall that many economists say that the ECB should target 2%. More relevant: in July ’21, many economists surveyed were uncertain if ‘Current EU and national fiscal policy plans are likely to leave European output below potential a year from now.’[129] And while the stimulus in the EU was lower, the ECB worried that US expansion could trigger a sustained global increase in traded goods prices, and force the ECB to tighten monetary policy sooner than it is currently intending.[130] Also, note that the EU has more automatic stabilizers[131] and unemployment didn’t spike as much during the pandemic.[132] Finally, the EU has very high inflation dispersion now (see above) and very different automatic stabilizers, fiscal policy and high inflation volatility and dispersion. This is especially disruptive if you need to coordinate fiscal policy amongst many countries.

Furman said that ‘Inflation was likely higher because of unexpected factors but probably not much higher.’ Also, perhaps inflation doves created the environment for such surprise by boosting their voices while pushing back on those who raised concerns about inflation.

As the ECB president said recently,

‘We are really operating in different environments with different economic data. [For instance] our demand here in the euro-area is pretty much back to where it was pre-COVID. In the US it is 30% up.[...] why? Because of this massive fiscal stimulus that the U.S. economy has had, unlike the euro area, where it has been more moderate, not excessive and which is producing the measured pace at which some factors are significantly improving.’[133]

Weak claim: Risk was hard to predict and was only a mistake ex-post

To be fair:

Many economists were surprised by recent high inflation[134] and ‘Despite the surge in liquidity, central banks routinely predicted zero inflation for at least three years into the future along with interest rates remaining at zero.’[135]

In May ’21, a private-sector survey forecasted 2.3% inflation for ’21 and only a 0.5% chance of inflation +4%.[136]

In June ’21, a survey asked economists if ‘the current combination of US fiscal and monetary policy poses a serious risk of prolonged higher inflation’ and most were uncertain[137]—when asked again in Nov ’21, most agreed.[138]

Also, OpenPhil anticipated that the orgs they funded ‘might continue to advocate for lower rates at a point where we think it would no longer be helpful’[139].

But even if the risk from inflation was hard to predict, a weaker claim is that ex-post the ’21 grants were harmful. So there should be a post-mortem, and more analysis, due diligence, and/or transparency going forward, especially as macroeconomic policy advocacy is such a large lever.

General issues with Macroeconomics advocacy

Some have argued that lay people can know better than experts like central bankers.[140],[141] But maybe macroeconomics is too complex and we should be more epistemically modest[142] and defer to technocrats. Even Furman, who OpenPhil trusts,[143] is ‘uncertain and nervous about the trajectory of inflation’.[144] No one at OpenPhil works on macroeconomics full-time, yet they influence this very complex subject.[145]

‘Utilitarianism is a dangerous tool in the hands of well-intended people who reason poorly and ill-intended people who reason well.’[146]

In other words, if you pull a very big lever that you’re not confident is not robustly good to pull, you need to be more careful and increase the amount of analysis you do.

This might sound ironic coming from a non-expert. But I’m not claiming I can outperform experts ex-ante, i.e. prescribe what to do now or could have known better then. Indeed, in Aug ’21, I endorsed OpenPhil’s Macroeconomic stabilization program.[147] Rather, I’m ex-post pointing out a mistake and it could have been avoided had more analysis been done. Speculatively, the following biases that might have led to this:

too little epistemic modesty: too little analysis and due diligence was done for these grants

status quo bias / ‘being asleep at the wheel’: too little ongoing monitoring of the situation was done

not enough attention to unintended consequences (here: causing populism);

Technocratic blind spots: neglecting that despite an intervention being net good, for some it might be bad (cf. the ‘China shock’ literature)

Finally, lobbying (foreign) monetary policy part-time seems robustly problematic (Kelsey Piper comments on the reasoning intransparency of these grants[148]) and polemics might attack the problematic optics of ‘three former Bridgewater dudes lobbying foreign central banks part-time’.

‘Technopopulist pressures on the Fed can come from both the right and the left. For example, a left-wing populist group called the Fed Up Coalition pressures the Fed to support ‘regular folks who are struggling in the economy,’ and works with outside experts, including academic and think tank economists, to promote their high-priority cause of ‘full employment’ monetary policy. [See for instance a policy report on full employment monetary policy[149] that lists Fed Up, the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), and the Center for Popular Democracy as contributors.] Cox (’21) predicts that President Biden will be more cordial toward the Fed than President Trump was, but that a vocal wing in his party will push the Fed to help with pressing social issues like racial equality and climate change.’[150]

Also:

’Formal social systems intended to serve broad populations always have blind spots and biases that cannot be anticipated in advance by their designers. Historically, these blind spots often lead to disastrous outcomes if they are left unchecked by external input. If this input is left to the outcome stage, disasters must occur before the system is reconsidered rather than biases being caught during the process. Failures of technocracy in managing economic and computational systems today bear significant responsibility for widespread feelings of illegitimacy that threaten respect for the best-grounded science that technocrats believe is most important for the public to trust.

Technical insights and designs are best able to avoid this problem when, whatever their analytic provenance, they can be conveyed in a simple and clear way to the public, allowing them to be critiqued, recombined, and deployed by a variety of members of the public outside the technical class.

Technical experts therefore have a critical role precisely if they can make their technical insights part of a social and democratic conversation that stretches well beyond the role for democratic participation imagined by technocrats. Ensuring this role cannot be separated from the work of design.

Technocracy divorced from the need for public communication and accountability is thus a dangerous ideology that distracts technical experts from the valuable role they can play by tempting them to assume undue, independent power and influence. [...] Many technocrats are at least open to a degree of ultimate popular sovereignty over government, but believe that such democratic checks should operate at a quite high level, evaluating government performance on ‘final outcomes’ rather than the means of achieving these.’[151] (But see criticism[152])

Implications and recommendations

If the above is true, we should:

Stop making similar grants

Try to quantify the harm that was caused (as in the ‘China shock’ literature)

Ask grantees to consider arguments against inflation

Increase research transparency in this area

Do more analysis for particularly leveraged interventions, especially those with an unclear sign

Reconsider funding advocacy of foreign central banks

Instead of populist advocacy, fund academic research on Optimal Monetary Policy[153], Optimal Inflation Rate[154], Optimal Automatic Stabilizers[155] (very little work has been done[156]. Also see ‘How to boost unemployment insurance as a macroeconomic stabilizer’[157]), and Optimal Spatial policies (‘fostering employment growth in regions beset by chronic joblessness may help workers hurt by persistent negative local labor demand shocks. On optimal spatial policies [...] employment impacts of labor demand shocks are larger in local markets in which joblessness was initially high [...] job growth in distressed regions is especially beneficial for low-wage workers.’[158]).

Fund more expert surveys like the IGM Survey of economists

Fund more research on greater international monetary policy coordination or a stronger role for IMF in monetary system would affect poorer countries

Fund research on the implications of crypto on monetary policy. In expectation, Crypto could disrupt monetary policy and the consequences and alternatives (e.g. central bank digital currencies) seem understudied i.e. this is a very neglected field.

[1] Two tentative concerns about OpenPhil’s Macroeconomic Stabilization Policy work—EA Forum

[2] Despite billions of extra funding, small donors can still have a significant impact—EA Forum

[3] So You Want To Run A Microgrants Program

[4] Inflation Target—IGM Forum

[5] Objectives of the European Central Bank—IGM Forum

[6] World Economic Outlook Update, January 2022: Rising Caseloads, A Disrupted Recovery, and Higher Inflation

[7] Annual inflation up to 5.9% in the euro area

[8] Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, December ’21

[9] Euro area annual inflation up to 5.8%

[10] Eurozone inflation dispersion

[11] Consumer Price Index Summary - ’21 M12 Results

[12] Red-Hot Inflation Grips Pockets of US Midwest and South With Rates Over 9% - Bloomberg

[13] Trimmed Mean PCE Inflation Rate—Dallasfed.org

[16] Interest Rate Spreads | FRED | St. Louis Fed

[18] https://www.philadelphiafed.org/surveys-and-data/real-time-data-research/spf-q4-’21

[19] Global Dimensions of US Monetary Policy | NBER

[20] Globalization: What’s at stake for central banks | VOX, CEPR Policy Portal

[21] Russia’s central bank raises interest rates to five-year high | Financial Times

[22] Can tourism ease the inflation pressure in Turkey? - BBC News

[23] Inflation tracker: latest figures as countries grapple with rising prices | Financial Times

[24] FAO Food Price Index | World Food Situation

[25] Monetary Policy and its Transmission in a Globalized World

[26] The Fed—Are Rising US Interest Rates Destabilizing for Emerging Market Economies?.

[27] World Employment and Social Outlook | Trends 2022

[28] Asymmetric Growth and Institutions in an Interdependent World Daron Acemoglu James A. Robinson Thierry Verdier

[29] Growth and the case against randomista development—EA Forum

[30] Inflation volatility in small and large advanced open economies

[31] The dispersion of inflation across the euro area countries and the US metropolitan areas

[32] Inflation: Concepts, Evolution, and Correlates

[33] Experimental CPI for lower and higher income households

[34] Monetary policy shocks and inflation inequality

[35] https://www.atlantafed.org/chcs/wage-growth-tracker

[36] Unemployment Rates for States

[37] https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1489331272795054083.html

[38] A Multisector Perspective on Wage Stagnation by Rachel Ngai, Orhun Sevinc

[39] What the Heck Is Going on With the US Economy? - The New York Times

[40] Inflation Drives Wages Down, Not Up—WSJ

[41] twitter.com/jasonfurman/status/1492200686238511105

[42] Wage Growth Tracker—Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

[43] Could Putin’s War Crash the US Economy? - Plain English with Derek Thompson | Podcast on Spotify

[44] US wages grew at fastest pace in decades in ’21, but prices grew even more | PIIE

[45] In which ways does inflation harm the poor? - Marginal REVOLUTION

[46] On inflation as a regressive consumption tax—ScienceDirect

[47] Could Putin’s War Crash the US Economy? - Plain English with Derek Thompson | Podcast on Spotify

[48] Inflation politics is clearer than inflation economics

[49] Americans Expect Inflation to Persist Over Next Six Months

[50] Great Inflation Surge of ’21 | Mercatus Center

[51] Americans Expect Inflation to Persist Over Next Six Months

[53] Inflation politics is clearer than inflation economics

[55] Biden’s job approval sinking on inflation, crime and COVID: POLL—ABC News

[56] Great Inflation Surge of ’21 | Mercatus Center

[57] 2024 winning party | Politics odds | Smarkets betting exchange

[58] Senate Results 2022 Winner Betting Odds | Politics | Oddschecker

[59] 2022 House Of Representatives Election Winner Betting Odds | Politics | Oddschecker

[60] 2022 House And Senate Elections Politics odds | Smarkets betting exchange

[61] 2022 House and Senate control | Politics odds | Smarkets betting exchange

[62] Inflation could cost Democrats control of Congress—Vox

[63] An Early Midterm Forecast

[64] Moskovitz’s Transformation into a Democratic Mega-donor

[65] Europe’s Monetary Policy Will Lead to a Populist Surge | Martens Centre

[66] Steigende Preise: Inflation ist toxisch—Kolumne—DER SPIEGEL

[67] Do Conservative Central Bankers Weaken the Chances of Conservative Politicians?

[68] Resolving Debt Overhang: Political Constraints in the Aftermath of Financial Crises*

[69] Political instability and inflation volatility | SpringerLink

[71] Importing Political Polarization?

[72] Global Competition and Brexit | American Political Science Review | Cambridge Core

[73] Who voted for Brexit? A comprehensive district-level analysis | Economic Policy | Oxford Academic

[74] The Happiness Trade-Off between Unemployment and Inflation

[75] Q&A: David Autor on the long afterlife of the ‘China shock’ | MIT News

[78] Technopopulism and Central Banks by Carola Binder

[79] Global Supply Chains—IGM Forum

[80] https://t.co/DvgPy2nCG6

[82] Inflation Debate between Krugman and Summers

[83] The old inflation playbook no longer applies | FT

[84] https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/why-us-inflation-surged-2021-and-what-fed-should-do-control-it

[86] Personal communication

[87] As inflation rises, the monetarist dog is having its day | Financial Times

[88] Ben Ritz on Twitter: ‘blaming inflation on supply chain bottlenecks is like blaming car crashes on whatever object the car slammed into.’

[89] Market Probability Tracker—Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

[90] Global bonds knocked as traders brace for central bank tightening | Financial Times

[91] ‘People are unhappy’: Fed official warns on high inflation—CNN

[92] Understanding the Fed’s Hawkish Pivot—by Joseph Politano

[93] Fed’s expected policy will be ‘too little too late’ on inflation, economists fear | Financial Times

[94] A Note on the Fed’s Power to Lower Inflation

[96] What is causing inflation? Economists point fingers at different culprits

[98] What Are You Expecting? How The Fed Slows Down Inflation Through The Labor Market

[99] Opinion | Biden Keeps Blaming the Supply Chain for Inflation. That’s Dishonest. - The New York Times

[100] Was Larry Summers Right All Along?

[102] The ‘old inflation playbook’ still applies—Econlib

[103] https://open.spotify.com/episode/2jYmY8LNvKJgLBZU3MT0b1

[104] How Tight are US Labor Markets? | NBER

[105] Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco | Searching for Maximum Employment

[106] The real story behind last week’s jobs report

[107] America’s economic recovery is about to go into reverse—CNN

[108] Grants Database | Open Philanthropy

[109] Alexander Berger on improving global health and wellbeing in clear and direct ways − 80,000 Hours

[110] Macroeconomic Policy | Open Philanthropy.

[111] Technopopulism and Central Banks by Carola Binder

[112] ’21 in the Rearview: December FOMC Recap

[113] Google Translate of Dezernat Zukunft blog

[114] Google Translate of Dezernat Zukunft blog

[115] 5-Year Breakeven Inflation Rate (T5YIE) | FRED | St. Louis Fed

[116] Nerd Out Over the Two Flavors of Inflation, CPI and PCE—Bloomberg

[117] Decomposing market-based measures of inflation compensation into inflation expectations and risk premia

[118] Interest Rate Spreads | FRED | St. Louis Fed

[119] Employ America — General Support (’21) | Open Philanthropy

[120] Dezernat Zukunft — General Support and Re-Granting | Open Philanthropy

[121] Google Translate of Dezernat Zukunft blog

[122] https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/why-us-inflation-surged-2021-and-what-fed-should-do-control-it

[123] 30-year Breakeven Inflation Rate (T30YIEM) | FRED | St. Louis Fed

[124] In defense of concerns over the $1.9 trillion relief plan

[125] 25th Annual Financial Markets Conference May 17-18, ’21 - Fed

[126] What Do Price Equations Say About Future Inflation?

[127] German and European Economic Policy—IGM Forum

[128] Fiscal and Monetary Policy—IGM Forum

[129] Fiscal and Monetary Policy—IGM Forum

[130] US Macroeconomic Policy Response to COVID-19: Spillovers to the Euro Area

[131] Objectives of the European Central Bank—IGM Forum

[132] Unemployment rate forecast—OECD Data

[133] Lagarde comments at ECB press conference | Reuters

[134] Paul Krugman on the Year of Inflation Infamy | Mercatus Center

[135] Is money demand really unstable? Evidence from Divisia monetary aggregates

[136] Why Did Almost Nobody See Inflation Coming? by Jason Furman

[140] Chapter 1 | Inadequate Equilibria

[141] Central banks should have listened to Eliezer Yudkowsky—Econlib

[142] In defence of epistemic modesty—EA Forum

[143] https://twitter.com/albrgr/status/1491095499616956416

[144] Jason Furman on Twitter: ‘I’m uncertain about the trajectory of inflation. But even conditional on my inflation views, I’m even more uncertain about what exactly monetary policy should do. Nervous about overreacting but also nervous about being so far from a reasonable place now. So just, well, nervous.’

[145] ‘We do not currently have a full-time staff member dedicated to this cause. Alexander Berger leads our grantmaking in this area.’ The new hire Peter Favaloro who took over is not an expert or working full-time on this either

[146] Self-Serving utilitarian arguments | Amanda Askell

[147] Decreasing populism and improving democracy, evidence-based policy, and rationality—EA Forum.

[148] Hits-based Giving | Open Philanthropy

[149] The Full Employment Mandate of the Federal Reserve: Its Origins and Importance—Center for Economic and Policy Research

[150] Technopopulism and Central Banks by Carola Binder

[151] Why I Am Not a Technocrat—EA Forum

[152] On weyl’s ‘why i am not a technocrat’

[153] Optimal Monetary Policy with Heterogeneous Agents Sept 2019

[154] On the Optimal Inflation Rate—American Economic Association

[155] Optimal Automatic Stabilizers | The Review of Economic Studies | Oxford Academic

[156] Automatic stabilizers and economic crisis: US vs. Europe

[157] How to boost unemployment insurance as a macroeconomic stabilizer: Lessons from the 2020 pandemic programs | Economic Policy Institute

[158] On the Persistence of the China Shock | NBER

[159] Inflation Target—IGM Forum

[160] Objectives of the European Central Bank—IGM Forum

[161] Annual inflation up to 5.9% in the euro area

[162] Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, December ’21

[163] Interest Rate Spreads | FRED | St. Louis Fed

[164] Euro area annual inflation up to 5.8%

[165] Eurozone inflation dispersion

[167] https://www.philadelphiafed.org/surveys-and-data/real-time-data-research/spf-q4-’21

[168] Inflation could cost Democrats control of Congress—Vox

[169] An Early Midterm Forecast

[170] What Do Price Equations Say About Future Inflation?

[171] Fiscal and Monetary Policy—IGM Forum

[172] 25th Annual Financial Markets Conference May 17-18, ’21 - Fed

[173] In defense of concerns over the $1.9 trillion relief plan

[174] German and European Economic Policy—IGM Forum

[175] Moskovitz’s Transformation into a Democratic Mega-donor

- Four categories of effective altruism critiques by (9 Apr 2022 15:48 UTC; 100 points)

- EA Updates for April 2022 by (31 Mar 2022 16:43 UTC; 32 points)

- 's comment on In a time of rapid change, we should re-examine system-level interventions by (10 Mar 2025 12:18 UTC; 17 points)

- 's comment on Unflattering aspects of Effective Altruism by (16 Mar 2024 5:42 UTC; 12 points)

- Should I invest my runway? by (9 Jul 2022 10:22 UTC; 8 points)

- 's comment on Two tentative concerns about OpenPhil’s Macroeconomic Stabilization Policy work by (24 Mar 2022 23:59 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on Announcing a contest: EA Criticism and Red Teaming by (29 Jun 2022 17:55 UTC; 0 points)

- 's comment on Crowdsourcing The Best Ideas for Structural Democratic Reforms by (8 Nov 2024 18:01 UTC; -1 points)

Thanks for this! I oversee the Macroeconomic Stabilization grant portfolio at Open Phil. We’ve been reevaluating this issue area in light of the current macroeconomic conditions and policy landscape, and we’re planning to write more about our own perspective on this in the future—so I won’t reply line by line here. But we’re always eager for substantive external critique, so I wanted to flag that we’d seen this and appreciate you sharing!

One clarifying question: are you suggesting that we could reduce inflation risks without running higher unemployment in expectation? From my perspective, a dovish macroeconomic policy framework has both costs and benefits. We’re generally going to face too-high inflation at one part of the business cycle and too-high unemployment at another part of the cycle. A philanthropist could push for a more dovish framework in order to minimize the UE overshoot at the expense of risking more inflation overshoot. I see those two risks as trading off against each other—curious if you agree.

Thanks for engaging with this! I agree with all your points, but with some important qualifications.

Yes, in normal times, we can’t reduce inflation risks without risking losing any jobs and that there’s usually a trade-off. And so, as a rule, if we push for more dovish policy to lose fewer jobs, then we risk overshooting on inflation. Yes, there’s usually too-high inflation at one part of the cycle and too-high unemployment at another—it’s never optimal. But it depends on how ‘too-high’. We live in extraordinary times (even antebellum).

The US hasn’t had such high inflation and such low unemployment since the 60s, and surprisingly now, the flat Phillips curve need not imply that reducing inflation will cost many jobs at all [see recent paper by Fed officials]. Even Krugman now says that the job market is running unsustainably hot and says that this time reducing inflation won’t risk high unemployment (though the landing won’t be soft) and also ‘Cooling that market off will probably require accepting an uptick in the unemployment rate, although not a full-on recession.’ [src] The labor market is just very tight right now [also see this empirical paper]. And so, I don’t think that we always want to ‘minimize unemployment’. The jobs we’re adding are not probably not good jobs.

And yes, as you say, dovish policy has costs and benefits. And indeed, it created a lot of benefits up until a point and then it’s about the marginal cost-effectiveness. Because of diminishing returns, the high costs on the ’21 margin outweighed the benefits. So in essence, we way overshoot. As I write above:

And so it’s not a matter of dovish vs. hawkish, but a matter of degree. We were too dovish and overshoot.

Hard it may be to accept, but maybe Manchin was right and we shouldn’t have printed so much money and had such a big stimulus, and we all made fun of the guy on the left here:

but maybe he was onto to something.

Thanks a ton for this clarification! Very helpful.

Something I did not see mentioned here as a potential critique: Open Phil’s work on macro policy seemed to be motivated by a (questionable?) assumption of differing values from those who promote tighter policy. Here is Holden Karnofsky with Ezra Klein [I think the last sentence got transcribed poorly, but the point is clear]:

This struck me as a bit odd, because I think if you asked individuals more hawk-ish than Open Phil if they cared impartially about all Americans, they would answer yes. I suspect Open Phil may have overestimated the degree to which genuine technocratic disagreement was in fact a difference of values.

Maybe OP is/was right, but it would take significant technical expertise to identify which side of the debate is substantively correct, so as to conclude one side must not be motivated by impartial welfare.

I also think it’s prudent to assume that even hawkish central bankers are broadly impartial and welfarist (but maybe just place more emphasis on longterm growth).

But I think maybe OpenPhil’s general theory of change and reasoning is still plausibly correct for 2008-2020, and people systematically undervalued how bad unemployment was for wellbeing and were perhaps too worried about inflation for political reasons.

Holden and Open Philanthropy’s thinking about this is so bad.

“Learning all about macroeconomic policy” is obviously what they should have been doing. Making high-risk grants usefully requires doing the intellectual work to understand the arguments for each and every one of them yourself. Funding “a particular set of values that says full employment is very important if you kind of value all people equally and you care a lot about how the working class is doing and what their bargaining power is” is…

Oh dear.

Open Phil does do the intellectual work in some other areas. That Holden states they didn’t here, and tries to frame the fact that they didn’t as a good thing, indicates to me they are biased and should stay away from this area.

I don’t understand what you think Holden / OpenPhil’s bias is. I can see why they might have happened to be wrong, but I don’t see what in their process makes them systematically wrong in a particular way.

I also think it’s generally reasonable to form expectations about who in an expert disagreement is correct using heuristics that don’t directly engage with the content of the arguments. Such heuristics, again, can go wrong, but I think they still carry information, and I think we often have to ultimately rely on them when there’s just too many issues to investigate them all.

It’s not the kind of bias you’re thinking of; not a cognitive or epistemic bias, that is. It’s dovish bias, as in a bias to favor expansionary policy. The non-biased alternative would be a nondiscretionary target that does not systematically favor either expansionary or contractionary policy.

(If we want to talk about epistemic bias, and if I allow myself to be more provocative, there could also be a different kind of bias, social desirability: “you kind of value all people equally and you care a lot about how the working class is doing and what their bargaining power is” sounds good and is the kind of language you expect to find in a political party platform. This was in an interview and in a response prompted by Ezra Klein, but just seeing language like that used could be a red flag.)

Yes, but:

Not when making high-risk grants, where the value comes from your inside-view evaluations of the arguments for each grant (or category of grants, if you’re funding multiple people working on the same or similar things but you have evaluated these things for yourself in sufficient detail to be confident that the grants are overall worth doing).

Not as a substitute for directly engaging with the content of the arguments, but in addition to doing that and as a way to guide your engagement with the arguments (to help you see the context and know what arguments to look at). Unless you really don’t have the time to engage with the arguments, but there are a lot of hours in a year and this is kind of Open Philanthropy’s job.

Never while framing as a good thing the fact that you’re deferring to experts instead of engaging with the arguments yourself, never while implying that there would be something wrong about engaging with the arguments yourself instead of (or in addition to) deferring to experts.

What is your source for this claim? By contrast, this article says,

And they show this chart,

Here’s another article that cites economists saying the same thing.

The most recent source for this i Jason Furman on Twitter in March:

The first article you cite is only till October ’21 and 6 months can make a difference. I also agree with the claim of the second article you cite “Inflation is high, but wage gains for low-income workers are higher. For now”. This is equivalent to my claim saying: ‘More voters have seen their real wages go down than up (mostly in the lower income brackets)’. Indeed, the article you cite does say that real wages are down on average but lowest income workers might have seen small increases in real wages.

I want to understand the main claims of this post better. My understanding is that you have made the following chain of reasoning:

OpenPhil funded think tanks that advocated looser macroeconomic policy since 2014.

This had some non-trivial effect on actual macroeconomic policy in 2020-2022.

The result of this policy was to contribute to high inflation.

High inflation is bad for two reasons: (1) real wages decline, especially among the poor, (2) inflation causes populism, which may cause Democrats to lose the 2022 midterm elections.

Therefore, OpenPhil should not make similar grants in the future.

I’m with you on claims 1, 2, and 3. I’m not sure about 4 and 5. Let me focus on my confusions with claim 4.

In another comment, I pointed out that it wasn’t clear to me that inflation hurts low-wage workers by a substantial margin. Maybe the sources I cited there were poor, but it doesn’t seem like there’s a consensus about this issue to my (untrained) eyes.

The fact that prediction markets currently indicate that Republicans have an edge in the midterm elections is not surprising. FiveThirtyEight says, “One of the most ironclad rules in American politics is that the president’s party loses ground in midterm elections.” The only modern exception to this rule was the 2002 midterm election, in which Republicans gained seats because of 9/11.

If we look at ElectionBettingOdds, it appears that the main shock that pushed the markets in favor of a Republican win was the election last year. (see Senate, and House forecasts). It’s harder to see Republicans gaining due to inflation in the data (though I agree they probably did). EDIT: OK I think it’s more clear to me now that the spike in the House forecast in May 2021 was probably due to inflation concerns.

Here are some of my reasons for disliking high inflation, which I think are similar to the reasons of most economists:

Inflation makes long-term agreements harder, since they become less useful unless indexed for inflation.

Inflation imposes costs on holding wealth in safe, liquid forms such as bank accounts, or dollar bills. That leads people to hold more wealth in inflation-proof forms such as real estate, and less in bank accounts, reducing their ability to handle emergencies.

Inflation creates a wide variety of transaction costs: stores need to change their prices displays more often, consumers need to observe prices more frequently, people use ATMs more frequently, etc.

Inflation transfers wealth from people who stay in one job for a long time, to people who frequently switch jobs.

When inflation is close to zero, these costs are offset by the effects of inflation on unemployment. Those employment effects are only important when wage increases are near zero, whereas the costs of inflation increase in proportion to the inflation rate.

It’s quite nuanced. There are real wage declines on average, but some poor people might have seen small real wage increases, others might have seen real wage losses. For instance, older people’s wages seem stickier according to the wage tracker here. OpenPhil’s grantee EmployAmerica has an interesting analysis of the various factors, and one could perhaps reasonably disagree with that. But my analysis doesn’t hinge on the claim that real wages have definitely decreased, and I think the main idea still holds even if there have been small wage increases for some populations.

I agree that parties usually lose ground in the midterms, but even if you take that into account, the Democrats are doing particularly poorly.

I’ve lost a few citations due to a software error—which I’ve now fixed, but for completeness I wrote:

“Real income can predict midterms and naïve extrapolation of current income decline predict Democrats losing 50+ seats.”

Sources are:

https://www.vox.com/2022/2/21/22936218/inflation-biden-midterms-democrats

https://www.mischiefsoffaction.com/post/2022-midterm-forecast

So it’s beyond the scope of this post to quantify the exact impact, but it might not be trivial.

Would you say that OpenPhil’s grants in 2021 were negative impact, but that many of their previous grants were positive impact? You demonstrate quite convincingly that the 2021 grants were negative impact (if they had impact at all), pushing us from supporting employment and consumption post-Covid to triggering inflation. But OpenPhil’s macroeconomic policy grants date back to 2014, when the case for more expansionary monetary policy was much stronger.

The monetary consensus was significantly more hawkish during the recovery from the 2008 recession. The recovery was famously slow, and when OpenPhil began their grantmaking in the area in 2014, the US had not yet closed the output gap left by the 2008 recession. OpenPhil helped push us to a policy consensus that met the Covid-19 pandemic with swift and decisive rate-dropping and QE from the Fed, as well as the widely celebrated stimulus payments from Congress. Consider a counterfactual world where OpenPhil never made macroeconomic policy grants—would we have been in greater danger of underreacting to Covid just as we underreacted to 2008? What if greater concern for inflation had prevented the Congressional stimulus packages? How would the costs of higher unemployment, lower consumption, and stronger temporary shock to family consumption compare to the challenges of inflation we’re currently facing?

This deserves more attention and expertise than I have to offer, and your writeup is a stellar critique of a clear failure on the current margin. But the lessons learned from OpenPhil’s macroeconomics advocacy should cover the full extent of their program, and the case for positive impact seems much stronger in earlier years.

My vague sense is that you’re right and that until 2021, the program was very good and beneficial and helped with a faster recovery. I commend OpenPhil for engaging with this and I agree that we should evaluate the impact of the whole program, I just don’t have the capacity and means to do that. My vague sense is that the program would come out net positive on the whole, however, perhaps if there are large negative effects of current high inflation—like lots of populists getting elected and we can causally attribute this to high inflation- then it also doesn’t seem inconceivable that the overall impact might be negative. Similar to the China Trade Shock literature which showed that trade reform was beneficial for growth and lowered consumer prices slightly, but also might have helped Trump win, this might be similar, and I’d rather take a slightly slower recovery then another 4 years of Trump (but note that this could have gone the other way as well: perhaps a faster recovery in the past reduced the chance of Trump in 2016, helped Biden in 2020, and the low unemployment numbers will help the Democrats now actually—it’s really an empirical question).

I don’t know much about economics, but this section doesn’t support the claim in the title. It simply has the title stating the claim and then states Open Phil funded policy.

But there’s many steps between funding and the outcomes the post is predicated on. For example, Open Phil’s funding might have been clumsy and ineffective, or on the other hand, it may have funded sophisticated thinkers who anticipated today’s “problems”.

While you do touch on the issues, it’s unclear whether the post has a useful model for what is going on. Then, in a deep sense, then it’s unclear how it can claim advocacy is good or bad.

I think understanding the 1) link between the funding and what was actually performed, and 2) getting a model of inflation from macroeconomics is the hard part.

This literacy and precision seems hard and important. Even glimpses of what might be going on when Open Phil funds a think tank is valuable.

Yes, I haven’t analyzed the effectiveness of these grants in depth and indeed postulate that these grants are relatively effective given OpenPhil’s track record in other areas and also their self-evaluation (they themselves say the grants are effective). But yes I do cite one paper that argues that ‘Technopopulism and Central Banks’ arguing that such advocacy is not very ineffective.

One thing I did come across during my research is an interaction on Twitter between Furman—Obama’s former economic advisor—and the CEO of EmployAmerica. Furman tweeted something against loose policy and then the EmployAmerica CEO jumped in and corrected him on some numbers and Furnam actually updated towards are more dovish position (now he seems to be back towards being a bit more hawkish). Policymakers listen to Furnam… so that’s already one plausible datapoint for policy influence of OpenPhil’s grantee.

As such, I think it’s prudent to assume that OpenPhil had some influence on macroeconomic policy, but the effect size might be small. I actually do think that the effect size will likely be small because overall funding for these think tanks was relatively modest in 2021. But especially given their commitment to hits-based giving, in expectations the effect size could have been higher.

However, ultimately, I see the first order effects of the advocacy on the macroeconomy are perhaps not as important as the second order effects of making suboptimal grants on OpenPhil and the wider EA community (including reputational effects).

Thanks for this thoughtful reply with specific examples and knowledge.

It’s clear that you know more than me and have deep thoughts.

Just to be direct, I wanted to just list out and “punch through” a few further critiques on your post. In the process of doing this, this comment comes off as pretty negative, but this isn’t the goal. It just seems good to push through this.

I found it easy to ungenerously interpret content in your post as rhetoric. For example, I don’t fully understand the top 3 or 4 subsections on inflation, which occupies a lot of your post. This may be a deep and principled examination of inflation, but it also seems to be simply enumerating the downsides of inflation. Yet, everyone agrees the recent, sudden and continuing unexpected inflation is a concern and wants to stop it.

As mentioned in my comment above (and also below in this comment), I didn’t understand how the realized inflation was tied to Open Phil’s advocacy, which seems like the point of your post. Because of this and how it precedes the section on claiming the advocacy is bad, I found it easy to pattern match this inflation to something like rhetoric. This affected my perception or the aesthetics of the rest of your post.

In a more direct way, I interpret the section in the end as containing rhetoric, “too little epistemic modesty”, “Technocratic blind spots”. I understand the point you are making, but someone who doesn’t agree that the case has been made, this weakens the post by giving an easy way to ascribe existing beliefs to the author (which may not be fair).

COVID-19 seems like a “table flip” that needs to be addressed. I don’t think anyone really knows how inflation works or how to start or stop it perfectly. But I think we can agree the pandemic was a wild event and maybe there was wild economic action taken. This wild action alone could both cause inflation, or interact with any sort of advocacy that you are criticizing. This could completely swamp out the effects of this advocacy itself and makes judgement difficult. I didn’t really see a lot of consideration of this (or the counterfactual of different policies during the pandemic). This is hard, but touching on this in a way that seems balanced seems important.

Why set the date 2021 to divide good and bad advocacy? I’m really uncertain about the “2021” date that you choose to divide advocacy between good or bad. I think you are really committed to this date, and it comes up again in the comments. But I think that, even setting aside or completely accepting every other idea or claim in the post, it’s very likely that actions taken from 2014 to 2020, also influence inflation today in 2022. In fact, if you’re claiming the current inflation is bad, it seems plausible that underlying processes started in early in 2021 or 2020. It seems possible the inflation, in a physical logical sense, precedes the effects of the funding that you say is good/benign.

The reason why I wanted to write the comment above is just to air out the thoughts in it. I’m not sure but my sentiment is that I think this could ultimately enable you, maybe by going past the particular topic of inflation.

In your post, there are a lot of interesting points, and it feels like going for this directly would make awesome writing in itself:

In particular, your view on “technocracy” seems interesting. Why not examine this directly?

What exactly is technocracy? What does this term even mean (like, isn’t criticism of technocracy self-contradictory)? What is the inherent problem/challenges/tradeoffs of “using technocracy”, or not using it? A well informed, fully principled dissection/take down seems interesting and could occupy many posts.

Also, it seems like you could be enabled directly much more. Like, maybe you should have access to pretty candid interviews with the think tanks grantees on what their policy is, as well as Open Phil’s team. This means that you can take on some of the “implications and recommendations” that you bring up.

Maybe you are entitled to enablement in a compelling sense: I speculate/have information that your post, “Growth and the case against randomista development” might also be the highest rated post in the EA forum 10 year contest. So, like, you literally have the best post ever here. That seems important and an achievement for you and John Halstead.

Thanks for the feedback- all taken in good spirit :) This is helpful as it helps me clarify.

I’ll try to explain a few assumptions implicit in the post and not assume very much macroeconomics knowledge, so sorry if the following is trivial or comes across as didactic, but maybe I’ve skipped a few steps / assumed too much knowledge. It’s quite a complex topic and it’s hard to wrap your head around and keep everything in mind as there are so many moving parts, this is why I kept things quite tight and terse. Ezra Klein also said a similar thing in a recent podcast with Furman. I also focused on the ‘case against higher inflation’ while trying to be balanced at points and mentioning the upsides. The ambition was not to provide a deep and principled examination of inflation as a whole, but rather point towards potential dangers, which on the margin, is neglected in this community. There are very clear drawbacks also of having low inflation and sluggish recovery after 2008, but that was beyond the scope of this post. Also it was beyond the scope to tie OpenPhil’s advocacy to higher inflation—I provided some evidence for that but mostly postulated that it is true because they say they think they’ve had an effect on this in the past.

In macro, there’s a basic trade-off between unemployment and inflation (see more here). Politicians can create big stimulus packages and increase government debt, and that stimulates the economy and this creates jobs and leads to higher wages. More jobs lead to higher wages (c.f. Phillips curve—Wikipedia ), this leads to more inflation. If the stimulus is too big (above the output gap) of a recession, then you overshoot and the economy runs hot. Also, if the central bank prints too much money, keeps interest rates too low, or does quantitative easing, then this can of course also create inflation. There’s disagreement around the specifics, the time horizons, and how big the multipliers are and so on, but at the end of the day there’s economic consensus that at some point inflation will be too high, and you can only print so much money, and your stimulus can only be so big not to overheat the economy.

The basic causal model underlying this post is that OpenPhil’s grantees have advocated for bigger fiscal stimulus and also more expansionary monetary policy to create more jobs (e.g. funding ‘EmployAmerica’). This might have been correct after the sluggish recovery of 2008, where we should have been more expansionary, but now we’ve probably overshot.

So there’s a lot to unpack here in this sentence.

Only now, slowly, even the most dovish economists are coming around to thinking inflation is too high, and that we shouldn’t have been so loose in retrospect. Now the doves fade from view and even OpenPhil’s grantees write that now ‘it is more defensible to slow down the labor market for the sake of lower inflation’, after pushing a dovish stance for until recently.

It’s not very recent… inflation was already quite high last year, and also not very sudden: again already in May ’21, the futures markets predicted ~2.7% average inflation in the US over the next 5 years (which suggests it’s somewhat more persistent/continuing than those in team transitory might suggest) and an econometrics paper published then estimated a 32% chance of >6% inflation in 2022 and warned that the discussion was based on casual observation rather than econometrics. So the strong claim is that this wasn’t recent, sudden, unexpected and could have been predicted had OpenPhil put adequate resources towards analyzing this properly (which they don’t seem like they have). But the weak claim is that I’m just cherry picking the few people who correctly predicted that inflation is going to be bad (and there are many people who have ‘cried wolf’ on inflation and thus are not being listened to anymore… and many people joke that Larry Summers, who warned early about inflation last year, had to be right on something eventually). But if this turns out to be just a mistake ex-post, we might still perhaps learn from it.

I see what you’re pointing towards, and several reviewers indeed suggested taking out these sections, saying it weakens the piece, but I decided to leave them in, as I think it’s important. I could have just criticized the proximal cause of the mistake saying ‘We’ve caused too much inflation and this has bad effects and there were econometric models that predicted that, next time look at these models’. And then the response could have been ‘Oh well, mistakes were made, human error, hits-based giving, you win some, you lose some, we didn’t have such a big impact anyway at the size of the grants’. But I think there’s just something deeper and a bit crazy ‘big, if true’ stuff that’s amiss here, that I was trying to gesture at in those sections.

Like, if you really stop and think about it, that OpenPhil funded lobbying groups to influence foreign central banks, and then this was (if my analysis is correct, which might not be the case) not going in the correct direction, then that’s quite something. It’s not like they had funded something uncontroversially good (say human rights stuff abroad) and that had a bad side effect.

And I’d love to know what others think about that. More generally, on the margin, we have too much data in the EA community, and not enough theory.

The pandemic was of course unprecedented and was a unique challenge and inflation is this environment is challenging. However, even though there’s a kernel of truth to what you say with ‘nobody really knows how inflation works and how to start or stop it perfectly’ this is a bit like ‘throwing out the baby with the bathwater’. We have some ideas and I cite some economists who created models and BOTECs that for instance suggested that the stimulus was based on atheoretical casual observation and so arbitrarily decided and thus somewhat arbitrarily large. To me this seems a bit crazy. And even if things were a bit wild as you say, I think we can still criticize bad decisions here, and it doesn’t mean we should fund ‘wild’ advocacy.

2021 is of course a somewhat arbitrary cutoff point. Sometimes there are lag times from policy changes to the economy reacting, and then on top of that you have more lag from advocacy affecting policy change etc. So it’s not inconceivable that pre 2021 grants also had negative effects.

However, there were reasons for this:

OpenPhil made two grants in mid-2021 to Dezernat Zukunft and EmployAmerica.

It also relates to my ‘Strong claim: Risk could have been predicted before the event and loose policy was a mistake ex-ante’ in the sense that in 2021 there were some voices and some analysis that predicted the current inflation overshoot. I haven’t found serious analysis that predicted current very high inflation in 2020.

I think this would be beyond the scope of what I can take on currently. I refer the interested reader to the Weyl piece that I cite and also see how it contrasts with a recent post by Holden.