Population Ethics Without Axiology: A Framework

This post introduces a framework for thinking about population ethics: “population ethics without axiology.” In its last section, I sketch the implications of adopting my framework for evaluating the thesis of longtermism.

Before explaining what’s different about my proposal, I’ll describe what I understand to be the standard approach it seeks to replace, which I call “axiology-focused.” (Skip to the section SUMMARY: “Population ethics without axiology” for a summary of my proposal.)

The axiology-focused approach goes as follows. First, there’s the search for axiology, a theory of (intrinsic) value. (E.g., the axiology may state that good experiences are what’s valuable.) Then, there’s further discussion on whether ethics contains other independent parts or whether everything derives from that axiology. For instance, a consequentialist may frame their disagreement with deontology as follows. “Consequentialism is the view that making the world a better place is all that matters, while deontologists think that other things (e.g., rights, duties) matter more.” Similarly, someone could frame population-ethical disagreements as follows. “Some philosophers think that all that matters is more value in the world and less disvalue (“totalism”). Others hold that further considerations also matter – for instance, it seems odd to compare someone’s existence to never having been born, so we can discuss what it means to benefit a person in such contexts.”

In both examples, the discussion takes for granted that there’s something that’s valuable in itself. The still-open questions come afterward, after “here’s what’s valuable.”

In my view, the axiology-focused approach prematurely directs moral discourse toward particular answers. I want to outline what it could look like to “do population ethics” without an objective axiology or the assumption that “something has intrinsic value.”

To be clear, there’s a loose, subjective meaning of “axiology” where anyone who takes systematizing stances[1] on moral issues implicitly “has an axiology.” This subjective sense isn’t what I’m arguing against. Instead, I’m arguing against the stronger claim that there exists a “true theory of value” based on which some things are “objectively good” (good regardless of circumstance, independently of people’s interests/goals).[2]

(This doesn’t leave me with “anything goes.” In my sequence on moral anti-realism, I argued that rejecting moral realism doesn’t deserve any of the connotations people typically associate with “nihilism.” See also the endnote that follows this sentence.[3])

Note also that when I criticize the concept of “intrinsic value,” this isn’t about whether good things can outweigh bad things. Within my framework, one can still express beliefs like “specific states of the world are worthy of taking serious effort (and even risks, if necessary) to bring about.” Instead, I’m arguing against the idea that good things are good because of “intrinsic value.”

My alternative account, inspired by Johann Frick (who I’ll discuss more soon), says that things are good when they hold what we might call conditional value – when they stand in specific relation to people’s interests/goals. On this view, valuing the potential for happiness and flourishing in our long-run future isn’t a forced move. Instead, it depends on the nature and scope of existing people’s interests/goals and, for highly-morally-motivated people like effective altruists, on one’s favored notion of “doing the most moral/altruistic thing.”

Outlook

In the rest of this post:

I give a summary of my framework

I warn the reader how it can be challenging to understand one another when discussing reasoning frameworks as opposed to object-level claims

I give examples of the “axiology-focused” / “something has intrinsic value” outlook from effective altruist writings (so readers get a good sense of what I’m arguing against)

I introduce two building blocks to underscore my framework: Johann Frick’s critique of the “teleological conception of well-being” and David Heyd’s idea that issues of creation/procreation may be “outside the scope of ethics”

I introduce my framework at length (expanding on the summary; discussing applications; flowchart)

I mention some limits of my proposal and point to areas where further development seems necessary

I discuss the implications of my framework for evaluating longtermism (in short: all but the strongest formulations of longtermism still go through under plausible assumptions, but the distance between longtermism and alternative views shortens)

SUMMARY: “Population ethics without axiology”

Ethics is about interests/goals.

Nothing is intrinsically valuable, but various things can be conditionally valuable if grounded in someone’s interests/goals.

The rule “focus on interests/goals” has comparatively clear implications in fixed population contexts. The minimal morality of “don’t be a jerk” means we shouldn’t violate others’ interests/goals (and perhaps even help them where it’s easy and our comparative advantage). The ambitious morality of “do the most moral/altruistic thing” coincides with something like preference utilitarianism.

On creating new people/beings, “focus on interests/goals” no longer gives unambiguous results:[4]

The number of interests/goals isn’t fixed

The types of interests/goals aren’t fixed

This leaves population ethics under-defined with two different perspectives: that of existing or sure-to-exist people/beings (what they want from the future) and that of possible people/beings (what they want from their potential creators).

Without an objective axiology, any attempt to unify these perspectives involves subjective judgment calls.

People with the motivation to dedicate (some of) their life to “doing the most moral/altruistic thing” will want clear guidance on what to do/pursue. To get this, they must adopt personal (but defensible), population-ethically-complete specifications of the target concept of “doing the most moral/altruistic thing.”

Just like the concept “athletic fitness” has several defensible interpretations (e.g., the difference between a 100m sprinter and a marathon runner), so (I argue) does “doing the most moral/altruistic thing.”

In particular, there’s a tradeoff where cashing out this target concept primarily according to the perspective of other existing people leaves less room for altruism on the second perspective (that of newly created people/beings) and vice versa.

Accordingly, people can think of “population ethics” in several different (equally defensible)[5] ways:

Subjectivist person-affecting views: I pay attention to creating new people/beings only to the minimal degree of “don’t be a jerk” while focusing my caring budget on helping existing (and sure-to-exist) people/beings.

Subjectivist totalism: I count appeals from possible people/beings just as much as existing (or sure-to-exist) people/beings. On the question “Which appeals do I prioritize?” my view is, “Ones that see themselves as benefiting from being given a happy existence.”

Subjectivist anti-natalism: I count appeals from possible people/beings just as much as existing (or sure-to-exist) people/beings. On the question “Which appeals do I prioritize?” my view is, “Ones that don’t mind non-existence but care to avoid a negative existence.”

The above descriptions (non-exhaustively) represent “morality-inspired” views about what to do with the future. The minimal morality of “don’t be a jerk” still applies to each perspective and recommends cooperating with those who endorse different specifications of ambitious morality.

One arguably interesting feature of my framework is that it makes standard objections against person-affecting views no longer seem (as) problematic. A common opinion among effective altruists is that person-affecting views are difficult to make work.[6] In particular, the objection is that they give unacceptable answers to “What’s best for new people/beings.”[7] My framework highlights that maybe person-affecting views aren’t meant to answer that question. Instead, I’d argue that someone with a person-affecting view has answered a relevant earlier question so that “What’s best for new people/beings” no longer holds priority. Specifically, to the question “What’s the most moral altruistic/thing?,” they answered “Benefitting existing (or sure-to-exist) people/beings.” In that light, under-definedness around creating new people/beings is to be expected – it’s what happens when there’s a tradeoff between two possible values (here: the perspective of existing/sure-to-exist people and that of possible people) and someone decides that one option matters more than the other.

Ontology differences can impede successful communication

I see the axiology-focused approach, the view that “something has intrinsic value,” as an assumption in people’s ethical ontology.

The way I’m using it here, someone’s “ontology” consists of the concepts they use for thinking about a domain – how they conceptualize their option space. By proposing a framework for population ethics, I’m (implicitly) offering answers to questions like “What are we trying to figure out?”, “What makes for a good solution?” and “What are the concepts we want to use to reason successfully about this domain?”

Discussions about changing one’s reasoning framework can be challenging because people are accustomed to hearing object-level arguments and interpreting them within their preferred ontology.

For instance, when first encountering utilitarianism, someone who thinks about ethics primarily in terms of “there are fundamental rights; ethics is about the particular content of those rights” would be turned off. Utilitarianism doesn’t respect “fundamental rights,” so it’ll seem crazy to them. However, asking, “How does utilitarianism address the all-important issue of [concept that doesn’t exist within the utilitarian ontology]” begs the question. To give utilitarianism a fair hearing, someone with a rights-based ontology would have to ponder a more nuanced set of questions.

So, let it be noted that I’m arguing for a change to our reasoning frameworks. To get the most out of this post, I encourage readers with the “axiology-focused” ontology to try to fully inhabit[8] my alternative framework, even if that initially means reasoning in a way that could seem strange.

“Something has intrinsic value” – EA examples

To give readers a better sense of the “some things have intrinsic value” outlook and its prevalence, I’ll include examples from effective altruism.

From the Effective Altruism Forum Wiki article, Axiology:

Axiology, also known as theory of the good and value theory (in a narrow sense of that term), is a branch of normative ethics concerned with what kind of things and outcomes are morally good, or intrinsically valuable.

Clicking the hyperlink:

Intrinsic value (sometimes called terminal value) is the value something has for its own sake. Instrumental value is the value something has by virtue of its effects on other things.

From the Effective Altruism Forum Wiki article, Wellbeing:

Wellbeing (also called welfare) is what is good for a person, or what makes their life go well or is in a person’s interest. It is generally agreed that all plausible moral views regard wellbeing as having intrinsic value, with some views—welfarist views—holding that nothing but wellbeing is intrinsically valuable.

From the 80,000 Hours article, Longtermism: the moral significance of future generations:

However, the bottom line is that almost every philosopher who has worked on the issue doesn’t think we should discount the intrinsic value of welfare — i.e. from the point of view of the universe, one person’s happiness is worth just the same amount no matter when it occurs.

From the Utilitarianism.net website (written and maintained by effective altruists):

After all, when thinking about what makes some possible universe good, the most obvious answer is that it contains a predominance of awesome, flourishing lives. How could that not be better than a barren rock? Any view that denies this verdict is arguably too nihilistic and divorced from humane values to be worth taking seriously.

[...]

A core element of utilitarianism is welfarism—the view that only the welfare (also called well-being) of individuals determines how good a particular state of the world is. While consequentialists claim that what is right is to promote the amount of good in the world, welfarists specifically equate the good to be promoted with well-being.

The term well-being is used in philosophy to describe everything that is in itself good for someone—so-called intrinsic or basic welfare goods—as opposed to things that are only instrumentally good. For example, happiness is intrinsically good for you; it directly increases your well-being.

[...]

What things are in themselves good for a person? The diverging answers to this question give rise to a variety of theories of well-being, each of which regards different things as the components of well-being. The three main theories of well-being are hedonism, desire theories, and objective list theories.

Two building blocks

My alternative framework is based on two building blocks, which I’ll now introduce.

Against the teleological view of well-being – Johann Frick

This section draws from Johann Frick’s excellent paper Conditional Reasons and the Procreation Asymmetry.[9] Quotes by Frick show why I’m skeptical of “intrinsic value” and describe the type of account I’d replace it with.

To summarize, Frick criticizes the standard approach in population ethics for prematurely privileging an assumption, namely that well-being is something “to be promoted.” He points out that there’s an alternative: things matter conditionally because they’re grounded in someone’s interests/goals. His view is best understood in contrast to what it criticizes – “the teleological conception of well-being:”

According to the teleologist, the appropriate response to what is good or valuable is to promote it, ensuring that as much of it exists as possible; the proper response to disvalue is to prevent it, or to ensure that as little of it exists as possible.

Some teleological thinkers, such as G.E. Moore, see such a close connection between goodness and its promotion that Moore often characterizes the good in terms of “what ought to exist”.

[...]

Next, note that viewing some value F as to be promoted implies that there is no deep moral distinction between increasing the degree to which F is realized amongst existing potential bearers of that value, and creating new bearers of that value.

[...]

By treating the moral significance of persons and their well-being as derivative of their contribution to valuable states of affairs, it reverses what strikes most of us as the correct order of dependence. Human wellbeing matters because people matter – not vice versa.

Frick also makes an analogy between procreation and promise-making: just like it’s good to keep promises if one makes them, the things that fulfill people’s interests/goals are good if they (the people) are created.

Unlike Frick, I’m not advocating a particular normative theory, so I’m not saying the analogy between procreating and promise-making is the only way to think about the matter. My framework is compatible with (a subjectivist version of) totalism in population ethics (which doesn’t contain a procreation asymmetry). However, I concede that views with a procreation asymmetry become more viable options under Frick’s changed conception of well-being / why well-being matters.

Population ethics as “outside the scope of ethics” – David Heyd

I’ll discuss passages from David Heyd’s book Genethics to introduce the second building block. (The term “Genethics” never caught on – the field became known as “population ethics” instead.)

The Introduction to Heyd’s book is titled “Playing God” – an excellent perspective for illustrating the issues under discussion.

The question is whether value itself is attached only to human beings (or another defined group of moral subjects), or if it can also be ascribed to impersonal states of the world. If value can be attached only to moral subjects, then the question of their creation escapes value judgment. For how can the prehuman world be evaluated (as e.g., inferior to the world populated with human subjects) if there is in it no “anchor” to which value can be attached? [...] In terms of the story of creation, when God sees that everything he had made was “very good,” is it very good for him, very good for created humanity, or very good simpliciter?

Heyd’s last sentence captures a core component of my proposal. Following Frick’s point that value is conditional value (no objective axiology; no grounding perspective from which to evaluate what’s “good simpliciter”), we’re left with two different perspectives. First, that of existing people/beings (in Heyd’s example, God all by himself). Second, that of possible people/beings (here: humanity, perhaps alongside other possible civilizations God could have contemplated creating). The last perspective Heyd discusses, that of “good simpliciter,” is non-existent.

Heyd also made some noteworthy observations on methodological challenges:

Not to know the answer to an important question is bad enough. Not to know how to go about solving it is even worse. [… I]t seems that they [“Genesis problems,” i.e., matters of creation of new people/beings] also prompt a sense of methodological uneasiness, raising doubts concerning the definition and scope of basic ethical concepts, the validity of certain methods of justification in ethical argumentation, and indeed the very limits of ethics.

Indeed, another core claim in my framework is that there are issues within population ethics for which there’s no objective answer.

“Population ethics without axiology”

I’ll now sketch my framework. I’ll proceed in the following order.

Background assumptions and (further) building blocks

Complements and elucidates the points from the summary (here’s the link in case you want to re-read it)

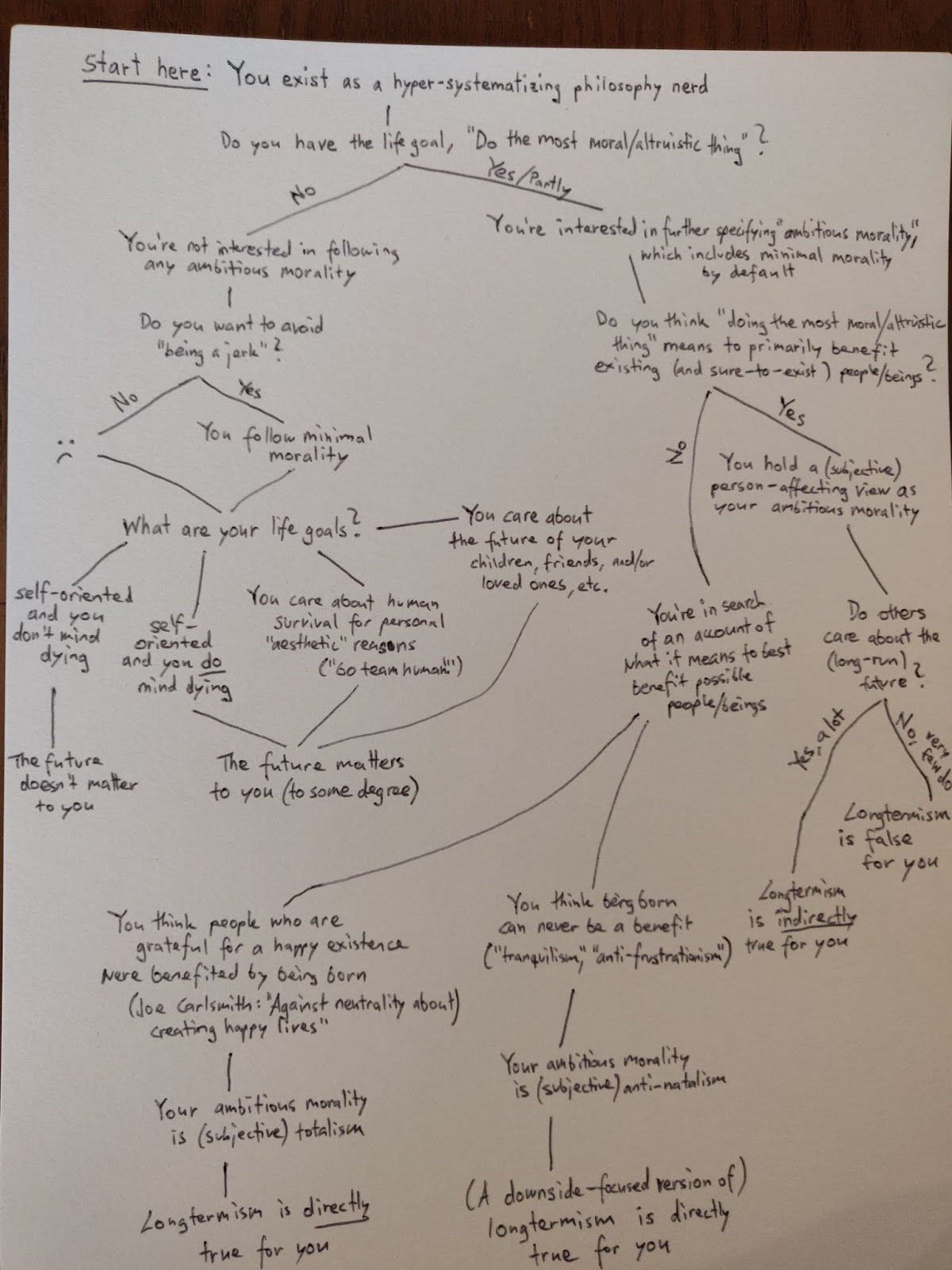

Caring about the future: a flowchart

Visualizes the workings of my framework and its option space

Applications (examples)

Ideas for filling in further assumptions when applying the framework

Background assumptions and (further) building blocks

Ethics is about interests/goals.

“There’s no objective axiology” implies (among other things) that there’s no goal that’s correct for everyone who’s self-oriented to adopt. Accordingly, goals can differ between people (see my post, The Life-Goals Framework: How I Reason About Morality as an Anti-Realist). There are, I think, good reasons for conceptualizing ethics as being about goals/interests. (Dismantling Hedonism-inspired Moral Realism explains why I don’t see ethics as being about experiences. Against Irreducible Normativity explains why I don’t see much use in conceptualizing ethics as being about things we can’t express in non-normative terminology.)

“Outside the scope of (normal) ethics.”

In my ontology, “population ethics” is no longer a crisp domain with a single answer. Instead, it has areas where the approach “focus on interests/goals” leaves things under-defined. These include “How to unify the two perspectives – that of existing people and that of newly(-to-be-) created people?” and “To the degree that we care about what’s best for possible people, which appeals should we prioritize when we cannot do right by everyone?”

How do we know the views of possible people?

We can’t talk to not-yet-existing people. When I discuss what possible people/beings want, I imagine a scenario where they come to exist and we ask them questions about how they’d compare their existence to a hypothetical where they had never been born. (If you think this approach is very subjective – that’s partly my point.)

There’s a tension between the beliefs “there’s an objective axiology” and “people are free to choose their life goals.”

Many effective altruists hesitate to say, “One of you must be wrong!” when one person cares greatly about living forever while the other doesn’t.[10] By contrast, when two people disagree on population ethics “One of you must be wrong!” seems to be the standard (implicit) opinion. I think these two attitudes are in tension. To the degree people are confident that life goals are up to the individual to decide/pursue, I suggest they lean in on this belief. I expect that resolving the tension in that way – leaning in on the belief “people are free to choose their life goals;” giving up on “there’s an axiology that applies to everyone” – makes my framework more intuitive and gives a better sense of what the framework is for, what it’s trying to accomplish.

Minimal morality vs. ambitious morality.

My framework creates space for a distinction between minimal morality and ambitious mortality.

Minimal morality is “don’t be a jerk” – it’s about respecting that others’ interests/goals may be different from yours. It is low-demanding, therefore compatible with non-moral life goals. It is “contractualist”[11] or “cooperation-focused” in spirit, but in a sense that stays nice even without an expectation of reciprocity.[12]

Ambitious morality is “doing the most moral/altruistic thing.” It is “care-morality,” “consequentialist” in spirit. It’s relevant for morally-motivated individuals (like effective altruists) for whom minimal morality isn’t demanding enough.

That said, minimal morality isn’t just a low-demanding version of ambitious morality. In many contexts, it has its own authority – something that wouldn’t make sense within the axiology-focused framework. (After all, if an objective axiology governed all aspects of morality, a “low-demanding” morality would still be directed toward that axiology.)[13] In my framework, minimal morality is axiology-independent – it protects everyone’s interests/goals, not just those of proponents of a particular axiology.

Admittedly, there are specific contexts where minimal morality is like a low-demanding version of ambitious morality. Namely, contexts where “care-morality” and “cooperation-morality” have the most overlap. For instance, say we’re thinking about moral reasons towards a specific person with well-defined interests/goals and we’re equal to them in terms of “capability levels” (e.g., we cannot grant all their wishes with god-like power, so empowering them is the best way to advance their goals). In that scenario, “care-morality” and “cooperation-morality” arguably fall together. Since it seems reasonable to assume that the other person knows what’s best for them, promoting their interests/goals from a cooperative standpoint should amount to the same thing as helping them from a care/altruism standpoint.[14]

Still, cooperation-morality and care-morality come apart in contexts where others’ interests/goals aren’t fixed:

(1) Someone has under-defined interests/goals.

(2) It’s under-defined how many people/beings with interests/goals there will be.

(3) It’s under-defined which interests/goals a new person will have.

In such contexts, cooperation-morality says “pick a permissible option.” Highly-morally-motivated people will likely find that unsatisfying and want to go beyond it. Instead of “let’s not be jerks,” they want to do what’s best for others. They want (ambitious) care-morality: to figure out and apply what it means to “do the most moral/altruistic thing.”Without an objective axiology, this target concept is under-defined. Accordingly, different(ly)-morally-motivated people may fill in the gaps in different ways. At first glance, this looks like it could create tensions.

However, because minimal morality has its own authority, altruists with different conceptions of ambitious morality should endorse “don’t be jerks” towards each other, too. When we look at the motivation to develop and adopt some ambitious morality, that motivation doesn’t say minimal morality is wrong – only that it’s incomplete. Effective altruists want to go beyond minimal morality, not against it.

Where people have well-specified interests/goals, it would be a preposterous conception of care-morality to stick someone into an experience machine against their will or kill them against their will to protect them from future suffering. So, whenever a single-minded specification of care-morality (e.g., “hedonistic utilitarianism” or “negative utilitarianism”) contradicts someone’s well-specified interests/goals, that type of care-morality seems misapplied and out of place.

Because ambitious morality is under-defined only in places where people’s interests/goals are under-defined, everything works out fine: Different morally-motivated individuals may come away with different specifications of ambitious morality, but they never endorse violating minimal morality.

Why specify ambitious morality at all?

If ambitious morality is under-defined, why not leave it at that? Why fill in the gaps with something subjective – doesn’t that go against the spirit of our motivation to “pursue what’s moral”?

Just like the concept “athletic fitness” has multiple defensible interpretations (e.g., the differences between a 100m sprinter, a marathon runner, and someone who exercises to minimize cardiovascular risks),[15] so does “doing the most moral/altruistic thing.” Suppose your childhood dream was to be ideally athletically fit. In that case, whether you should care about a specific interpretation of the target concept or embrace its under-definedness is an open question. My advice for resolving this question is “think about which aspects of fitness you feel most drawn to, if any.”[16]

Population ethics from the perspective of existing people.

Envision technologically-very-developed settlers standing in front of a giant garden: There’s all this unused land and a long potential future ahead of them – what do they want to do with it? How do they address various tradeoffs (e.g., risks of creating dystopian subcommunities)? From the perspective of existing people, population ethics is about figuring out how much we care about the long-run future (if at all) and what we want to make of it. I see this as more of an existentialist question (about meaning/purpose) than a moral one – though it becomes “also moral” for individuals who want to dedicate their lives to “doing the most moral/altruistic thing.”

Population ethics from the perspective of possible people.

Newly created beings are at the whims of their creators (e.g., children are vulnerable to their parents). However, “might makes right” is not an ideal even minimally-morally-inclined creators would endorse. We can view population ethics from the perspective of possible people/beings as a court hearing: possible people/beings speak up for their interests/goals. With potential creators who are only following the minimal morality of “don’t be jerks,” the possible people/beings must resort to complaints to hold their creators accountable. By contrast, towards altruistically-motivated potential creators, they can also make appeals.

Complaints vs. appeals.

Complaints: Something counts as a complaint if someone who cares about fairness (“don’t be a jerk”) cannot defensibly ignore your complaint – even if their goals otherwise don’t include concern for your well-being.

Appeals: Anything you want to ask of someone who is already motivated to benefit you.

Minimal morality applied to possible people/beings is about avoiding complaints; ambitious morality applied to them is about granting appeals. Because different possible people/beings make different appeals,[17] ambitious morality focused on possible people/beings is under-defined – specifying it requires further (“axiological”) judgment calls.

The tradeoff between benefiting sure-to-exist people/beings vs. possible people/beings.

In the summary, I wrote, “Cashing out that target concept [doing the most moral/altruistic thing] primarily according to the perspective of existing (and sure-to-exist) people leaves less room for altruism on the second perspective (that of possible people) and vice versa.”

By this, I mean we have to choose one or the other. Either our ambitious morality is primarily about existing (and sure-to-exist) people/beings, or we also want what’s best for possible people/beings. (While the latter doesn’t give possible people/beings more weight, the large numbers at stake will dominate in practice.)[18]

Caring about the future: a flowchart

Applications (examples)

I’ll now give some examples for applying my framework. I’m not particularly attached to any specifics. Instead, I’m mostly arguing in favor of a particular way of thinking about such principles, e.g., how to apply them, their reach, etc.

Population ethics for possible people/beings: applying the court hearing analogy

In my framework, population ethics for possible people/beings is like a court hearing where possible people/beings address their potential creators.

Creators interested in minimal morality can only be held accountable via complaints (i.e., possible people object they didn’t receive even the minimal consideration of “don’t be a jerk”).

Complaints examples:

Don’t create minds that regret being born.

Don’t create minds and place them in situations where their interests are only somewhat fulfilled if you could easily have provided them with better circumstances.

Don’t create minds destined for constant misery even if you also equipped them with a strict preference for existence over non-existence.

Note that these principles aren’t meant to be absolutes. Instead, there’s an implicit “unless you acted according to a defensible conception of what’s best for possible people/beings.”[19]

By contrast, potential creators dedicated to some (non-person-affecting) ambitious morality are motivated to benefit possible people/beings well beyond “avoiding complaints” – they want to hear out possible people/beings to learn what’s best for them.

Appeals might go like this:

Possible person A: Maximize my chances of coming into existence with a favorable life trajectory; I’m okay running some risk of landing in an unfavorable one.

Possible person B: Minimize my chances of coming to exist with an unfavorable life trajectory; compared to my non-existence, I wouldn’t feel grateful about coming to live.

Examples of minimal morality vs. ambitious morality

To illustrate the distinction, I’ll give examples of common-sense statements about the ethics of procreating/having children. I justify each statement via one of three principles:

Minimal morality

Ambitious morality

“People can choose their own goals”

Examples:

People are free to decide against becoming parents (“people can choose their own goals”).

Parents are free to want to have as many children as possible (“people can choose their own goals”), as long as the children are happy in expectation (“minimal morality”).

People are free to try to influence other people’s moral stances and parenting choices (“people can choose their own goals”) – for instance, Joanne could promote anti-natalism and Marianne could promote totalism (two different specifications of “ambitious morality”) – as long as their persuasion attempts remain within the boundaries of what is acceptable in a civil society (“minimal morality”).

All parents must provide a high degree of care for their children (“minimal morality”).

For comparison, readers may (on their own) think about how these examples would work within the axiology-focused framework, where the answer is usually some form of “it depends on the correct axiology.”

(In)famous population ethics problems

I’ll now sketch how one could apply my approach to familiar questions/issues in population ethics. One thing I want to highlight is how the distinction between minimal morality and ambitious morality can motivate person-affecting views (“ambitious morality focused on benefitting existing and sure-to-exist people/beings; minimal morality for possible people/beings.”)

Procreation asymmetries.

Minimal morality for possible people/beings contains a weak procreation asymmetry because “don’t create minds that wish they had never been born” is generally less morally demanding than “create happy minds who will be grateful for their existence.”[20] Arguably, it also contains a procreation asymmetry for the more substantial reason that creating a specific person singles them out from the sea of all possible people/beings in a way that “not creating them” does not.[21]

Ambitious morality comes in different specifications, some of which contain a procreation asymmetry, others don’t.

Subjectivist person-affecting views import the procreation asymmetry from minimal morality to possible people/beings while focusing their caring budget on existing (and sure-to-exist) people/beings. (“Preference utilitarianism for existing and sure-to-exist people/beings; minimal morality for possible people/beings.”)

Subjectivist (versions of) totalism and anti-natalism care about what’s best for possible people/beings, but they’re built on different accounts of how to best benefit this interest group.[22] (They follow minimal morality for existing and sure-to-exist people/beings.)

The transitivity of “better-than relations.”

According to minimal morality, it’s neutral to create the perfect life and (equally) neutral to create a merely quite good life. Treating these two outcomes equally seems incompatible with doing what’s best for newly created people/beings. However, minimal morality isn’t about “doing the most moral/altruistic thing,” so this seems fine.

For any ambitious morality, there’s an intuition that well-being differences in morally relevant others should always matter.[23] However, I think there’s an underappreciated justification/framing for person-affecting views where these views essentially say that possible people/beings are “morally relevant others” only according to minimal morality (so they are deliberately placed outside the scope of ambitious morality).

Independence of irrelevant alternatives (IAA).[24]

Same as above: both minimal morality and person-affecting views tend to violate the transitivity of better-than-relations or IAA (or both). For minimal morality, this is arguably fine because the goal isn’t to maximally benefit. For person-affecting ambitious morality, this is arguably fine because the view concentrates its caring budget on existing and sure-to-exist people/beings.

The repugnant conclusion.[25]

It makes a difference whether to turn an existing paradise-like population into a much larger, less happy-on-average population vs. whether we’re comparing two options for colonizing a far-away galaxy with new people/beings.[26]

In the first version of the repugnant conclusion, minimal morality toward sure-to-exist people prohibits lowering the life quality in the paradise-like population (unless sufficiently many paradise-inhabitants would endorse the change), so there’s no ambitious morality that could justify the repugnant conclusion here.

In the second version, different specifications of ambitious morality will give widely differing answers, ranging from “the smaller population is preferable” to “it doesn’t matter” or “it depends on how other existing people feel about the matter” to “the larger population is preferable.”

The pinprick argument.[27]

Same as above. It makes a difference whether to extinguish an existing paradise-like population because of a pinprick of discomfort/suffering vs. whether we’re contemplating the creation of a new paradise-like population (with a pinprick).

In the first version, minimal morality towards sure-to-exist people prohibits bringing about extinction.

Even in the second version, minimal morality towards sure-to-exist people arguably demands creating the paradise-like population.[28]

The non-identity problem.[29]

The non-identity problem remains tricky for minimal morality and person-affecting versions of ambitious morality.

I don’t feel like I have an optimal answer – the court hearing analogy leaves things under-defined.[30]

One pathway I find promising is thinking less about harming/benefitting a specific individual and more about whether we’re lending (sufficient) care/concern to the interests of newly created people/beings. As an interest group, the latter have their interests violated if someone creates mediocre-life-trajectory Cynthia instead of great-life-trajectory Ali, even if Cynthia herself wasn’t harmed.

Some recent work in population ethics explores similar directions; see this paper by Teruji Thomas or this one by Christopher Meacham (discussed here on the EA forum).[31]

Limitations and open questions

Now that I’ve described my framework, I want to note some of its limitations.

The exact reach of minimal morality is fuzzy/under-defined. How much is entailed by “don’t be a jerk?”

I haven’t provided any attempt to answer precisely how far-reaching minimal morality is, so I understand that my proposal may seem unsatisfying. That said, I think this sort of under-definedness[32] is okay –lots of things in ethics seem fuzzy.

The exact nature of (and justification for) minimal morality could be clearer.

While polishing this post, I read Richard Ngo’s new post Moral strategies at different capability levels. I found his framing illuminating and have tried to incorporate it in my post, but mostly with late-stage edits instead of some more principled approach.

The non-identity problem doesn’t yet have a satisfying answer within my framework.

(See my discussion in the previous section.)

I doubt that coming up with any specific solution to non-identity issues would change the practical priorities of effective altruists, but further work on this topic could help evaluate whether I’m perhaps shrugging deeper problems with my framework under the carpet.[33]

I don’t give a precise account of what it is about interests/goals that makes something conditionally valuable.

With my framework, I endorse some version of a “preference-based view,” but there are many different versions of that.[34] Working out a more concise theory of conditional value could be useful for further assessing my framework.

Recommendations for longtermists

In this EA forum post, Will MacAskill defines “longtermism” as follows:[35]

Longtermism is the view that positively influencing the longterm future is a key moral priority of our time.

Based on my framework, I have the following recommendations for people interested in evaluating or promoting longtermism:

Highlight the existence of alternative frameworks (alternatives to “something has intrinsic value”).

First off, my framework proposal is just that, a proposal. I don’t expect all longtermists to adopt it. Still, the framework seems valid to me. So far, many longtermists frame the discussion as though there’s no alternative to “something has intrinsic value.”Asking/caring about how much other people care about long-run outcomes.

In the axiology-focused framework, the degree to which longtermism applies is primarily a philosophical question (though the causal reach of our actions also matters). Also, when longtermism “applies,” it applies equally to everyone interested in moral action. By contrast, within my framework, the degree(s) to which longtermism applies can depend on existing people’s attitudes towards the long-run future.[36] I think there’s something justifiably off-putting about discussions of longtermism that neglect this perspective. For what it’s worth, I suspect that a non-trivial portion of people outside effective altruism care about long-run outcomes a great deal – just that they maybe care about them in ways that don’t necessarily reflect totalism/thorough-going aggregation for newly created people/beings. Overall, I see multiple benefits – both strategic (how longtermism is perceived) and normative (deciding between different degrees of “longtermism applies”) – to asking and caring about how others care about the long-run future.Emphasizing more the ways ethics is (likely) subjective.

When arguing in favor of (some version of) longtermism, I recommend flagging the possibility that there may not be an objective answer. Instead, I’d say something like the following. “Longtermism is a position many effective altruists endorse after contemplating what’s entailed by their motivation/commitment to ‘do the most good’. Here’s why: [Arguments that aim to appeal to people’s fundamental intuitions.]” (Another way of saying this is “encourage others to join by telling them what sort of future you’re fighting for and why.”)[37]Treating person-affecting views more fairly?

EA discourse about person-affecting views has sometimes been crude or overly simplistic.[38] I think the following angle on person-affecting views is underappreciated: “preference utilitarianism for existing (and sure-to-exist) people/beings, minimal morality for possible people/beings.” I agree that person-affecting views don’t give satisfying answers to “what’s best for possible people/beings,” but that seems fine! It’s only within the axiology-focused approach that a theory of population ethics must tell us what’s best for both possible people/beings and for existing (or sure-to-exist) people/beings simultaneously.

- ↩︎

As opposed to moral particularlism.

- ↩︎

See also the SEP article on “intrinsic value.”

- ↩︎

Quoting from this summary: In theism vs. atheism debates, atheists don’t replace ‘God’ with anything when they stop believing in him. By contrast, in realism vs. anti-realism debates, anti-realists continue to think there’s “structure” to the domain in question. What changes is how they interpret and relate to that structure. Accordingly, moral anti-realism doesn’t mean “anything goes.” Therefore, the label “nihilism,” which some people use synonymously with “normative anti-realism,” seems uncalled for. The version of anti-realism I defend in my sequence fits the slogan “Morality is ‘real’ but under-defined.” Under-definedness means that there are multiple defensible answers to some moral issues. In particular, people may come away with different moral beliefs depending on their evaluative criteria, what they’re interested in, which perspectives they choose to highlight, etc. Overall, the way some moral philosophers use “nihilism” interchangeably with “anti-realism” seems surprisingly unfair. Imagine if, in the free will debate, the proponents of libertarian free will pretended that compatibilist positions didn’t exist, that the only alternative to libertarian free will was “It makes no difference if you look left and right before crossing the street.”

- ↩︎

Technically, interests/goals aren’t necessarily fixed in fixed population contexts either, since we can imagine people with under-defined goals or goals that don’t mind being changed in specific ways.

- ↩︎

Readers may wonder why I’m confident that several interpretations are “equally defensible” as opposed to “the jury is still out.” I concede that I’m not certain. Still, “equally defensible interpretations” are my default view, whereas “there’s a single moral truth” would be a surprising discovery. Because of the is-ought problem, we have to “get normativity started” by stipulating some assumptions on what we care about. What makes up a “defensible interpretation of a domain” depends on the features we choose to highlight. (See Luke Muehlhauser’s post on Pluralistic Moral Reductionism or my discussion of “evaluation criteria” in various places along my moral anti-realism sequence.) In my framework, I highlight that “morality” seems to be about interests/goals. We can see why this framing has ambiguous applications in contexts where interests/goals aren’t fixed. Since I don’t see any uncontroversial/uncontested extension principles, it stands to argue that population ethics will remain under-defined. Sure, there’s a remote chance that a future philosopher will devise a brilliant argument that convinces everyone to adopt a particular normative theory. However, that seems far-fetched. (And even then, we could wonder if maybe that philosopher just happened to be good at rhetoric or that people’s moral intuitions became more homogenous in the meantime for reasons unrelated to normative truth.)

- ↩︎

For instance, Hilary Greaves (2017), on the neutrality required for asymmetric person-affecting views (where creating a miserable person is bad but failing to create a happy person is neutral), writes that “it turns out to be remarkably difficult to formulate any remotely acceptable axiology that captures this idea of ‘neutrality’.”

- ↩︎

E.g., person-affecting views may violate the independence of irrelevant alternatives or the transitivity of better-than relations. See this post for examples.

- ↩︎

For more – totally optional – context, see also the overview of my sequence on moral anti-realism, which fleshes out more of my thinking.

- ↩︎

Hat tip to Michael St Jules for his EA forum post on the topic.

- ↩︎

Provided both people are familiar with arguments for/against living forever. In practice, many people may not have engaged carefully with these arguments, so we should expect more people to want to live forever than it appears at first glance.

- ↩︎

We can distinguish between “low-demanding” and “high-demanding” versions of contractualism. Minimal morality is low-demanding contractualism. By contrast, “high-demanding contractualism” would demand from everyone to exclusively follow altruistic goals.

- ↩︎

In other words, I’m not talking about cooperation that’s optimally beneficial even for self-oriented goals. Instead, I’m mainly appealing to the pro-social instinct to follow fairness norms – which we can extend to fairness to animals or future generations, despite knowing that these interest groups cannot reciprocate.

- ↩︎

For instance, if hedonist axiology was objectively correct, then we could think of classical utilitarianism as “ambitious morality,” while “minimal morality” would be something like “the set of not-too-demanding social norms that produce the best consequences from a classical utilitarian perspective.”

- ↩︎

One caveat here is that people may have self-sacrificing goals. For instance, say John is an effective altruist who’s intent on spending all his efforts on making the world a better place. Here, it seems like caring about “John the person” comes apart from caring about “John the aspiring utilitarian robot.” Still, on a broad enough conception of “interests/goals,” it would always be better if John was doing well himself while accomplishing his altruistic goals. I often talk about “interests/goals” instead of just “goals” to highlight this difference. (In my vocabulary, “interests” aren’t always rationally endorsed, but they are essential to someone’s flourishing.)

- ↩︎

Professional athletes tend to overstrain their bodies to a point where specific health risks are increased compared to the healthiest cohorts.

- ↩︎

I also give further-reaching and more nuanced advice on how to think about issues related to “moral uncertainty,” “metaethical uncertainty,” etc., in my post The “Moral Uncertainty” Rabbit Hole, Fully Excavated. For a summary of action-relevant takeaways, see the section “Selected takeaways: good vs. bad reasons for deferring to (more) moral reflection.”

- ↩︎

For instance, some possible people would rather not be created than be at a small risk of experiencing intense suffering; others would gladly take significant risks since they care immensely about the chance of a happy existence.

- ↩︎

Since ambitious morality fills the gaps of minimal morality rather than overriding it, someone with an (in practice) “future-focused” view would still interact with existing and sure-to-exist people within the bounds of the social contract from minimal morality, even though there’s a sense in which “much more is at stake” for possible people/beings.

- ↩︎

For instance, someone who endorses subjectivist totalism as their ambitious morality could create a much larger number of slightly-happy individuals instead of a small number of very happy individuals without thereby violating the spirit of the second principle above. Their defense would be that they acted on a defensible notion of what’s best for possible people/beings (in aggregate, as an interest group).

- ↩︎

In typical circumstances, many courses of action are compatible with not pushing a child into a pond, whereas only one type of action is compatible with rescuing an already-drowning child. See this post by Katja Grace, who noted that person-affecting views structurally resemble the action-omission distinction around property rights.

- ↩︎

If I fail to create a happy life, I’m acting suboptimally towards the subset of possible people who’d wish to be in that spot – but I’m not necessarily doing anything to highlight that particular subset. (Other possible people who wouldn’t mind non-existence and others yet would want to be created, but only under more specific conditions/circumstances.) By contrast, when I make a person who wishes they had never been born, I singled out that particular person in the most real sense. If I could foresee that they would be unhappy, the excuse “Some other possible minds wouldn’t be unhappy in your shoes” isn’t defensible.

- ↩︎

For two possible perspectives and some arguments and considerations on both sides, see Joe Carlsmith’s post Against neutrality about creating happy lives and my post on tranquilism.

- ↩︎

I believe that this is the intuition why some effective altruists are outspoken against person-affecting views.

- ↩︎

See here for an example and an explanation of this principle.

- ↩︎

See here for a description.

- ↩︎

The fact that people rarely highlight this difference illustrates how the axiology-focused approach conceptualizes the philosophical option space in a strangely limited way.

- ↩︎

The pinprick argument is a thought experiment to highlight the absurd implications of negative utilitarianism as an objective morality. See this essay.

- ↩︎

Some existing people would (presumably) greatly prefer the paradise-population to come into existence, which seems a good enough reason for minimal morality to ask of us to push that button. (Minimal morality is mostly about avoiding causing harm, but there’s no principled reason never to include an obligation to benefit. The categorical action-omission of libertarianism seems too extreme! If all we had to do to further others’ goals were to push a button and accept a pinprick of disvalue on our ambitious morality, we’d be jerks not to press that button.)

- ↩︎

See here for an unfortunately-somewhat-lengthy introduction.

- ↩︎

As a side note, there’s a version of the non-identity problem where, instead of focusing on differences between people’s identities, we focus on differences between people’s types of interests/goals. Let’s say we create grateful-to-exist Ramon instead of detached-from-life Nadieshda. We did well by Ramon’s standards, even though Nadieshda would have counted as neutral in the same life trajectory. In a sense, we only benefitted Ramon because we got lucky that he felt like he was benefitted. Or maybe we even deliberately created him with the type of psychology that could be benefited this way. Is this okay? I’d say yes to some degree because we cannot act without implicitly influencing the interests of the people we create (and leaving things up to chance would be worse). However, it seems objectionable to use this in our favor to exploit newly created people and give them worse life circumstances.

- ↩︎

Hat tip to Michael St Jules again.

- ↩︎

There’s a relevant difference between something being under-defined in the sense of having fuzzy boundaries vs. under-defined in the sense of “depending on how you specify this, you end up with opposite answers to decision problems like the repugnant conclusion, etc.

- ↩︎

I believe that finding problems in specific thought experiments can unearth bigger justification issues with the larger framework – see also the post “future-proof ethics.”

- ↩︎

For instance, the difference between “satisfaction versions” and “object versions;” see this post by Michael ST Jules. “Population ethics without axiology” seems closer to object versions?

- ↩︎

He also introduces definitions for “strong longtermism” (“long-run outcomes are the thing we should be most concerned about” and “very strong longtermism” (“long-run outcomes are of overwhelming importance”).

- ↩︎

How many care and how much they care, or how much they would care if they were ideally informed – see the section on “idealized values” in this post.

- ↩︎

To be fair, I think many longtermists already do this.

- ↩︎

At the extreme, I remember framings that went like this. “Do you think the welfare of people in the future should be discounted, yes or no? If you think no, then you favor totalism in population ethics. Footnote: Some people also have person-affecting views but these are widely regarded to run into unworkable problems.”

- Winners of the EA Criticism and Red Teaming Contest by (Oct 1, 2022, 1:50 AM; 226 points)

- Getting on a different train: can Effective Altruism avoid collapsing into absurdity? by (Oct 7, 2022, 10:52 AM; 187 points)

- Announcing: EA Forum Podcast – Audio narrations of EA Forum posts by (Dec 5, 2022, 9:50 PM; 156 points)

- AI alignment researchers may have a comparative advantage in reducing s-risks by (Feb 15, 2023, 1:01 PM; 79 points)

- Solution to the two envelopes problem for moral weights by (Feb 19, 2024, 12:15 AM; 66 points)

- Minimalist views of wellbeing by (Jul 15, 2023, 10:18 AM; 58 points)

- AI alignment researchers may have a comparative advantage in reducing s-risks by (LessWrong; Feb 15, 2023, 1:01 PM; 49 points)

- 's comment on Critique of MacAskill’s “Is It Good to Make Happy People?” by (Aug 24, 2022, 11:05 AM; 27 points)

- 's comment on Winners of the EA Criticism and Red Teaming Contest by (Oct 5, 2022, 2:39 PM; 24 points)

- 's comment on Common-sense cases where “hypothetical future people” matter by (Aug 12, 2022, 2:47 PM; 23 points)

- 's comment on My favourite arguments against person-affecting views by (Apr 2, 2024, 1:15 PM; 23 points)

- 's comment on Critique of MacAskill’s “Is It Good to Make Happy People?” by (Aug 23, 2022, 11:21 AM; 22 points)

- Monthly Overload of EA—September 2022 by (Sep 1, 2022, 1:43 PM; 15 points)

- 's comment on Critique of MacAskill’s “Is It Good to Make Happy People?” by (Aug 23, 2022, 2:07 PM; 10 points)

- 's comment on Puzzles for Everyone by (Sep 12, 2022, 6:57 AM; 9 points)

- 's comment on Whose life matters more—a baby’s or an adult’s? by (Jan 7, 2024, 2:09 PM; 9 points)

- Solution to the two envelopes problem for moral weights by (LessWrong; Feb 19, 2024, 12:15 AM; 9 points)

- 's comment on My Skeptical Opinion on the Repugnant Conclusion by (May 28, 2024, 3:27 AM; 8 points)

- 's comment on Aim for conditional pauses by (Oct 1, 2023, 9:06 AM; 7 points)

- 's comment on The standard person-affecting view doesn’t solve the Repugnant Conclusion. by (Aug 23, 2022, 8:25 PM; 7 points)

- 's comment on Book Review: Going Infinite by (LessWrong; Oct 25, 2023, 2:54 PM; 7 points)

- Giving What We Can October Newsletter 2022 by (Nov 1, 2022, 3:08 AM; 6 points)

- 's comment on Population ethics and the value of variety by (LessWrong; Jun 27, 2024, 12:47 AM; 5 points)

- 's comment on Aim for conditional pauses by (Sep 30, 2023, 12:12 PM; 4 points)

- 's comment on Against population ethics by (Aug 16, 2022, 11:25 AM; 4 points)

- 's comment on Existential Choices Symposium with Will MacAskill and other special guests (3-5pm GMT Monday) by (Mar 17, 2025, 5:31 PM; 4 points)

- 's comment on Against population ethics by (LessWrong; Aug 16, 2022, 9:18 PM; 4 points)

- 's comment on The “Moral Uncertainty” Rabbit Hole, Fully Excavated by (Mar 27, 2024, 2:15 PM; 2 points)

I like this post; as you note, we’ve been thinking along very similar lines. But you reach different conclusions than I do—in particular, I disagree that “the ambitious morality of “do the most moral/altruistic thing” is something like preference utilitarianism.” In other words, I think most of your arguments about minimal morality are still consistent with having an axiology.

I didn’t read your post very carefully, but I think the source of the disagreement is that you’re conflating objectivity/subjectivity with respect to the moral actor and objectivity/subjectivity with respect to the moral patient.

More specifically: let’s say that I’m a moral actor, and I have some axiology. I might agree that this axiology is not objective: it’s just my own idiosyncratic axiology. But it nevertheless might be non-subjective with respect to moral patients, in the sense that my axiology says that some experiences have value regardless of what the people having those experiences want. So I could be a hedonist despite thinking that hedonism isn’t the objectively-correct axiology.

This distinction also helps resolve the tension between “there’s an objective axiology” and “people are free to choose their own life goals”: the objective axiology of what’s good for a person might in part depend on what they want.

Having an axiology which says things like “my account of welfare is partly determined by hedonic experiences and partly by preferences and partly by how human-like the agent is” may seem unparsimonious, but I think that’s just what it means for humans to have complex values. And then, as you note, we can also follow minimal (cooperation) morality for people who are currently alive, and balance that with maximizing the welfare of people who don’t yet exist.

Thanks! Those points sound like they’re quite compatible with my framework.

tl;dr: When I said that “in fixed population contexts, the ambitious mortality of ‘do the most moral/altruistic thing’ is something like preference utilitarianism,” that was a very simplified point for the summary. It would be more accurate of the overall post if I had said something more like “In fixed population, fixed interests/goals contexts, any ambitious morality of […] would have a lot of practical overlap with something like preference utilitarianism.” Also, my post is indeed compatible with having an axiology yourself that differs from other people’s takes – a more accurate title for my post would be “population ethics without an objective axiology.”

To reply in more depth:

The part you’re quoting is specifically about a fixed population context and the simplifying assumption that people there have “fixed” interests/goals. As I acknowledge in endnote 4: “Technically, interests/goals aren’t necessarily fixed in fixed population contexts either, since we can imagine people with under-defined goals or goals that don’t mind being changed in specific ways.” So, the main point about ambitious morality being something like preference utilitarianism in fixed population contexts is the claim that care-morality and cooperation-morality overlap for practical purposes in contexts where interests/goals are (completely) fixed. I discuss this in more depth in the section “Minimal morality vs. ambitious morality:”

Endnote14:

[...]

As you can see in endnote 14, I consider “preference utilitarianism” itself under-defined and have sympathies for a view that doesn’t just listen to the rational, planning part of people’s brains (e.g., someone saying “I’m a hardcore effective altruist; I don’t rationally endorse caring intrinsically about my personal well-being”). I’d also consider that humans are biological creatures with “interests” – a system-1 “monkey brain” with its own needs, separate (or at least separable) from idealized self-identities that the rational, planning part of our brain may come up with. So, if we also want to fulfill these interests/needs, that could be justification for a quasi-hedonistic view or for the type of mixed view that you advocate?

They are! That’s how I meant my post. An earlier title for my post that I had in a draft was “Population ethics without an objective axiology” – I later shortened it to make the title more catchy.

As I say in the summary:

Subjectivist person-affecting views: [..]

Subjectivist totalism: [...]

Subjectivist anti-natalism: [...]

At least the second and third examples here, which are examples of specifications of ambitious morality, can be described as having a (subjective) axiology!

I also mention the adjective “axiological” later in the post in the same context of “if we want to specify what’s happening here, we need a (subjective) axiology:”

You say further:

That describes really well how I intended it. The “place” for ambitious morality / axiology is wherever cooperation-morality leaves anything under-defined. It isn’t the only defensible axiology the way I see it, but I very much consider (subjective and cooperative) hedonism a viable option within my framework.

Makes sense, glad we’re on the same page!

Perhaps consider changing it to that, then? Since I’m a subjectivist, I consider all axiologies subjective—and therefore “without axiology” is very different from “without objective axiology”.

(I feel like I would have understood that our arguments were consistent either if the title had been different, or if I’d read the post more carefully—but alas, neither condition held.)

I like this justification for hedonism. I suspect that a version of this is the only justification that will actually hold up in the long term, once we’ve more thoroughly internalized qualia anti-realism.

Thanks for writing this — I’m curious about approaches like this, and your post felt unusually comprehensive. I also don’t yet feel like I could faithfully represent your view to someone else, possibly because I read this fairly quickly.

Some scattered thoughts / questions below, written in a rush. I expect some or many of them are fairly confused! NNTR.

On this framework, on what grounds can someone not “defensibly ignore” another’s complaint? Am I right in thinking this is because ignoring some complaints means frustrating others’ goals or preferences, and not frustrating others’ goals or preferences is indefensible, as long as we care about getting along/cooperating at all (minimal morality)?

You say The exact reach of minimal morality is fuzzy/under-defined. How much is entailed by “don’t be a jerk?”. This seems important. For instance, you might see ‘drowning child’ framings as (compellling) efforts to move charitable giving within the purview of “you’re a jerk if you don’t do this when you comfortably could.” Especially given the size of the stakes, could you imagine certain longtermist causes like “protecting future generations” similarly being framed as a component of minimal morality?

One speculative way you could do this: you described ‘minimal morality’ as “contractualist” or “cooperation-focused” in spirit. Certainly some acts seem wrong because they just massively undermine the potential for many people living at the same time with many different goals to cooperate on whatever their goals are. But maybe there are some ways in which we collaborate/cooperate/make contracts across (large stretches of) time. Maybe this could ground obligations to future people in minimal morality terms.

I understand the difference in emphasis between saying that the moral significance of people’s well-being is derivative of its contribution to valuable states of affairs, as contrasted with saying that what makes states of affairs valuable just is people’s well-being (or something to that effect). But I’m curious what this means in a decision-relevant sense?

Here’s an analogy: my daily walk isn’t important because it increases the counter on my podometer; rather the counter matters because it says something about how much I’ve walked (and walking is the thing I really care about). To see this, consider that intervening on the counter without actually walking does not matter at all.

But unlike this analogy, fans of axiology might say that “the value of a state of affairs” is not a measure of what matters (actual people and their well-being) that can be manipulated independently of those things; rather it is defined in terms of what you say actually matters, so there is no substantial disagreement beyond one of emphasis (this is why I don’t think I’m on board with ‘further thought’ complaints against aggregative consequentialism). Curious what I’m missing here, though I realise this is maybe also a distraction.

I found the “court hearing analogy” and the overall discussion of population ethics in terms of the anticipated complains/appeals/preferences of future people a bit confusing (because, as you point out, it’s not clear how it makes sense in light of the non-identity problem). In particular your tentative solution of talking about the interests of ‘interest groups’ seems like it’s kind of veering into the axiological territory that you wanted to avoid, no? As in: groups don’t literally have desires or preferences or goals or interests above and beyond the individuals that make them up. But we can’t compare across individuals here, so it’s not clear how we can meaningfully compare the interests of groups in this sense. So what are we comparing? Well, groups can be said to have different kinds of intrinsic value, and while that value could be manifested/realised/determined only by individuals, you can comfortably compare value across groups with different sets of individuals.

Am I right in thinking that in order to creatively duck things like the RP, pinprick argument, arguments against asymmetry (etc) you are rejecting that there is a meaningful “better than” relation between certain states of affairs in population ethics contexts? If so this seems somewhat implausible because there do seem to be some cases where one state of affairs is better than another, and views which say “sure, some comparisons are clear, but others are vague or subjective” seem complicated. Do you just need to opt out of the entire game of “some states of affairs are better than other states of affairs (discontinuous with our own world)”? Curious how you frame this in your own mind.

I had an overall sense that you are both explaining the broad themes of an alternative to populaiton ethics grounded in axiology; and then building your own richer view on top of that (with the court hearing analogy, distinction between minimal and ambitious morality, etc), such that your own view is like a plausible instance of this broad family of alternatives, but doesn’t obviously follow from the original motivation for an alternative? Is that roughly right?

I also had a sense that you could have written a similar post just focused on simpler kinds of aggregative consequentialism (maybe you have in other posts, afraid I haven’t read them all); in some sense you picked an especially ambitious challenge in (i) developing a perspective on ethics that can be applied broadly; and then (ii) applying it to an especially complex part of ethics. So double props I guess!

Thanks for these questions! Your descriptions capture what I meant in most bullet points, but there are some areas where I think I failed to communicate some features of my position.

I’ll reply to your points in a different order than you made them (because that makes a few things easier). I’ll also make several comments in a thread rather than replying to everything at once

That’s right! I’m not particularly attached to the details of the court hearing analogy, for instance. By contrast, the distinction between minimal morality and ambitious morality feels quite central to my framework. I wouldn’t know how to motivate person-affecting views without it. Better developing and explaining my intuition “person-affecting views are more palatable than many people seem to give them credit for” was one of the key motivations I had in writing the post.

(However, like I say in my post’s introduction and the summary, my framework is compatible with subjectivist totalism – if someone wants to dedicate their life toward an ambitious morality of classical total utilitarianism and cooperate with people with other goals in the style of minimal morality, that works perfectly well within the framework [and is even compatible with all the details I suggested for how I would flesh out and apply the framework].)

Yeah. I think the distinction between minimal morality and ambitious morality could have been a standalone post. For what it’s worth, my impression is that many moral anti-realists in EA already internalized something like this distinction. That is, even anti-realists who already know what to value (as opposed to feeling very uncertain and deferring the point where they form convictions to a time after more moral reflection or to the output of a hypothetical “reflection procedure”) tend to respect the fact that others have different goals. I don’t think that’s just because they think they are cooperating with aliens. Instead, as anti-realists, they are perfectly aware that their way of looking at morality isn’t the only one, so they understand they’d need to be jerks in some sense to disrespect others’ goals or moral convictions.

In any case, explaining this distinction took up some space. Then, I added examples and discussions of population ethics issues because I thought a good way to explain the framework is by showing how it handles some of the dilemma cases people are already familiar with.

(Probably you meant to say “and [] frustrating others’ goals or preferences is indefensible”?)

Yes, that’s what it’s about on a first pass. Other things that matter:

The lesser of several evils is always defensible.

If it would be quite demanding to avoid thwarting someone’s interests/goals, then thwarting is defensible. [Minimal morality is low-demanding.]

Yes, I do see the drowning child thought experiment as an example where minimal morality applies!

Regarding “protecting future generations as a component of minimal morality:”

My framework could maybe be adapted to incorporate this, but I suspect it would be difficult to make a coherent version of the framework where the reason we’d (fully/always) count newly created future generations (and “cooperating through time” framings) don’t somehow re-introduce the assumption “something has intrinsic value.” I’d say the most central, most unalterable building blocks of my framework are “don’t use ‘intrinsic value’ (or related concepts) in your framing of the option space” and “think about ethics (at least partly) from the perspective of interests/goals.” So, to argue that minimal morality includes protecting our ability to bring future generations into existence (and actually doing this) regardless of present generations’ concerns about this, you’d have to explain why it’s indefensible/being a jerk to prioritize existing people over people who could exist. The relevant arguments I brought up against this are this section, which includes endnote 21 for my main argument. I’ll quote them here:

And here the endnote:

A key ingredient to my argument is that there’s no “universal psychology” that makes all possible people have the same interests/goals or the same way of thinking about existence vs. non-existence. Therefore, we can’t say “being born into a happy life is good for anyone.” At best, we could say “being born into a happy life is good for the sort of person who would find themselves grateful for it and would start to argue for totalist population ethics once they’re alive.” This begs the question: What about happy people who develop a different view on population ethics?

I develop this theme in a bunch of places throughout the article, for instance in places where I comment on the specific ways interests/goals-based ethics seem under-defined:

Point (3) in particular is sometimes under-appreciated. Without an objective axiology, I don’t think we can generalize about what’s good for newly created people/beings – there’s always the question “Which ones??”

Accordingly, there (IMO) seems to be an asymmetry here related to how creating a particular person singles out that particular person’s psychology in a way that not creating anyone does not. When you create a particular person, you better make sure that this particular person doesn’t object to what you did.

(You could argue that we just have to create happy people who will be grateful for their existence – but that would still feel a bit arbitrary in the sense that you’re singling out a particular type of psychology (why focus on people with the potential for gratefulness to exist?), and it would imply things like “creating a happy Buddhist monk has no moral value, but creating a happy life-hungry enterprenuer or explorer has great moral value.” In the other direction, you could challenge the basis for my asymmetry by calling into question whether only looking at a new mind’s self-assessment about their existence is too weak to prevent bad things. You could ask “What if we created a mind that doesn’t mind being in misery? Would it be permissible to engineer slaves who don’t mind working hard under miserable conditions?” In reply to that, I’d point out how even if the mind ranks death after being born as worse than anything else, that doesn’t make it okay to bring such a conflicted being into existence. The particular mind in question wouldn’t object to what you did, but nowhere in your decision to create that particular mind did you show any concern for newly created people/beings – otherwise you’d have created minds that don’t let you exploit them maximally and don’t have the type of psychology that puts them into internally conflicted states like “ARRRGHH PAIN ARRRGHH PAIN ARRRGHH PAIN, but I have to keep existing, have to keep going!!!” You’d only ever create that particular type of mind if you wanted to get away with not having to care about the mind’s well-being, and this isn’t a defensible motive under minimal morality.)

At this point, I want to emphasize that the main appeal of minimal morality is that it’s really uncontroversial. Whether potential people count the same as existing and sure-to-exist people is quite a controversial issue. My framework doesn’t say “possible people don’t count.” It only says that it’s wrong to think everyone has to care about potential happy future people.

All that said, the fact that EAs exist who stake most or even all of their caring budget on helping future generations come into a flourishing existence is an indirect reason why minimal morality may include caring for future generations! So, minimal morality takes this detour – which you might find a counterintuitive reason to care about the future, but nonetheless – where one reason people should care about future generations (in low-demanding ways) is because many other existing people care strongly and sincerely about there being future generations.

This description doesn’t quite resonate with me. Maybe it’s close, though. I would rephrase it as something like “We can often say that one outcome is meaningfully better than another outcome on some list of evaluation criteria, but there’s no objective list of evaluation criteria that everyone ought to follow. (But that’s just a rephrasing of the central point “there’s no objective axiology.”)

I want to emphasize that I agree that, e.g., there’s an important sense in which creating a merely medium-happy person is worse than creating a very happy person. My framework allows for this type of better-than relation even though my framework also says “person-affecting views are a defensible systematization of ambitious morality.” How are these two takes compatible? Here, I point out that person-affecting views aren’t about what’s best for newly created people/beings. Person-affecting views, the way I motivate them in my framework, would be about doing what’s best for existing and sure-to-exist people/beings. Sometimes, existing and sure-to-exist people/beings want to bring new people/beings into existence. In those cases, we need some guidance about things like whether it’s permissible to bring unhappy people into existence. My solution: minimal morality already has a few things to say about how not to create new people/beings. So, person-affecting views are essentially about maximally benefitting the interests/goals of existing people/beings without overstepping minimal morality when it comes to new people/beings.

The above explains how my view “creatively ducks” arguments against the asymmetry.

I wouldn’t necessarily say that my view ducks the repugnant conclusion – at least not in all instances! Mostly, my view avoids versions of the repugnant conclusion where the initial paradise-like population is already actual. This also means it blocks the very repugnant conclusion. By contrast, when it comes to a choice between colonizing a new galaxy with either a small paradise-like population or a very large population with people with lower but still positive life quality, my framework actually says “both of these are compatible with minimal morality.”

(Personally, I’ve always found the repugnant conclusion a lot less problematic when it plays out with entirely new people in a far-away galaxy.)

I don’t think my use of “interest groups” smuggles in the need for an objective axiology, but I agree that I should flesh out better how I think about this. (The way it’s currently in the text, it’s hard to interpret how I’m thinking of it.)