Questioning the Value of Extinction Risk Reduction

Note: Red Team 8 consists of [redacted], [redacted], Aaron Bergman, Jac Liew, and Hasan Asim.

Summary and Table of Contents

This post is a response to the thesis of Jan Brauner and Friederike Grosse-Holz’s post The Expected Value of Extinction Risk Reduction Is Positive. Below, we lay out key uncertainties about the value of extinction risk reduction (ERR) and more generally describe why it could be negative in expectation.

We highly recommend reading Jan and Friederike’s post as well as Anthony DiGiovanni’s A longtermist critique of “The expected value of extinction risk reduction is positive” to better understand the topic, key claims, and existing literature.

Our post has four main sections, each of which were written mostly independently and can be read separately and in any order:

The distinction between different extinction risks and existential risks: The value of preventing human extinction depends on the way we go extinct. The extinction of all life on earth could be positive if you think the current world is net negative (e.g. due to wild animal suffering), and you think the current state of the world will continue. However, human extinction without the destruction of nature would be negative assuming that only humans could end the current suffering. In both ways, this question can only be answered by extrapolating the human trajectory. If you believed humans are likely to create more suffering than positive experiences in the future, you could argue that human survival would be a bad outcome. Additionally you have to model whether we will be replaced by other earth-originating life, aliens or AGI to conclude whether our extinction would be negative. I, [redacted] conclude that the expected value of extinction risk reduction is mainly determined by tail outcomes. Since optimizers toward morally valuable things are more likely than optimizers towards morally disvaluable things, very positive futures are more likely and thus human survival would be positive.

A case for “suffering-leaning ethics”: Aaron critiques an existing argument that any amount of harm can in principle be morally justified by a large enough benefit. He argues there is no compelling reason to assume that a harm (benefit) can be represented by some finite negative (positive) real number and therefore that–even under standard utilitarian assumptions–one might conclude that some amounts of suffering are not morally justified by an arbitrarily large amount of happiness. The section concludes with a discussion of how and why this might affect the moral value of extinction risk reduction.

The value of today’s world: The value of the world today is likely to be dominated by non-human animals due to their vast quantities. The average welfare of animals is probably negative. Therefore, the extinction of all life on earth is positive for person-affecting views. Human’s impact on animal welfare is plausibly positive, due to the reduction of wild animals. This increases the person-affecting views’ expected value of ERR. It is unclear whether animal consumption is net positive or negative and beef consumption is likely to be net positive. Other considerations such as ecological damages and retributivism could affect the value of the world.

Possible negative futures and the need to give them appropriate attention: considering how bad the future could be updates us that human extinction may be the lesser evil.

(Bonus) Each author’s credence that the expected value of extinction risk reduction is positive. We encourage you not to skip ahead to this section.

Background and epistemic status

We came together as a team and produced this report as part of Training for Good’s Red Teaming Challenge. Each author began with relatively little background knowledge and understood the project in large part as an opportunity to learn more.

It is important to note that our explicit goal was to critique the claim in question, and we committed to this “side” of the debate before engaging in a significant amount of research. That said, we have refrained (or, at least, we’ve tried to) from making any arguments or claims that we believe to be wrong or misleading even if such an argument might serve our narrow interest to appear compelling.

What we do hope to show is that that the case for extinction risk reduction is neither straightforward nor certain. We also encourage readers to engage critically with the arguments for and against ERR and ask that you refrain from deferring to our conclusions.

Reducing the Risk of Extinction vs Reducing Existential Risk

by [redacted]

Epistemic status of this section:

I have spent much less time on this than I had hoped. I think I have managed to lay out some interesting counter-intuitive considerations with a strong focus on the negatives. However, my current view differs considerably from this as I briefly describe in the conclusion. Spending a few more hours researching the topic would likely update the presented arguments and my own view significantly.

Before assessing the value of extinction risk reduction, it may be helpful to distinguish between “extinction risk” and“existential risk” or “x-risk.” While the terms are sometimes – if only implicitly – used interchangeably, they have substantially different meanings and implications. In the first section, we clarify our use of terminology.

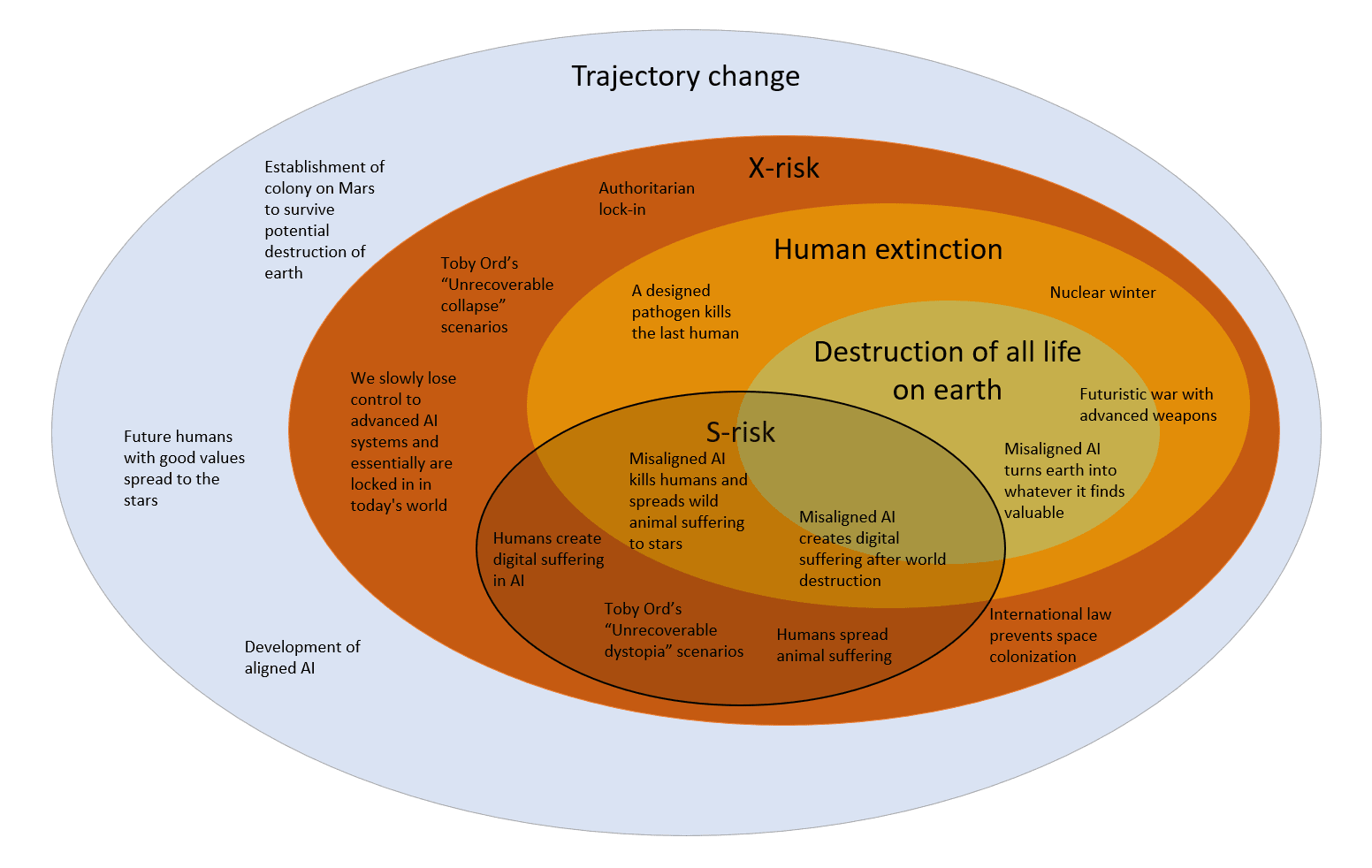

Classification of Pivotal Events Affecting Humanity

Pivotal events affecting the long-run future can be understood using the following simplified model.

A trajectory change is any event substantially and persistently impacting the long-term future

Existential risks or “x-risks” are those trajectory changes that threaten the destruction of humanity’s “long-term potential” by eliminating our possibility of any of the best possible futures.

(Human) extinction is a subset of x-risks.

Human extinction may or may not come as part of the destruction of all life on earth. As we explain below, this distinction may be important to the question at hand.

Finally, another way we could lose our future potential is through risks of astronomical suffering (s-risks): Events leading to the creation of a world filled with suffering beings.

To understand the intersections in this Venn diagram, we now give some examples of each case (note that this isn’t an attempt to quantify the likelihood of any of the events, so the sizes of each section are meaningless).

The key point to note is that x-risk comes in many forms and cause areas. These varying x-risks may have very different impacts on the future (ex. in how destructive they are, what preventative measures to take, and what level of importance they merit).

Here, we are trying to answer the question “Is the value of reducing the risk of human extinction positive?” I.e. Are endeavors to delay the end of humanity increasing the value of the world? Phrased even simpler, is it ‘good’ (positive) to prevent human extinction?

As depicted, different paths to extinction have vastly different outcomes. Let’s have a closer look.

Extinction of All Life on Earth

Advanced nanotechnology or dangerous weapons used in future wars as well as the most severe forms of asteroid impacts or other risks from outer space may lead to the extinction of all life on earth. While this would mean the end of the human legacy and a huge miss of our potential, it also means the end of all suffering, both in humans and non-human animals. It seems possible that animals in the wilderness are on average having net negative lives: As I ([redacted]) understand it, wild animal suffering is still a speculative cause area but I think it is fairly likely that most animal lives in the wild are dominated by suffering due to the evolutionary pressure to produce more offspring than can be supported by the environment and the resulting hunger and frustration. Furthermore, many animals in the wild are eaten alive or plagued by diseases and parasites. If one assumes that most animal lives today are not worth living, from a strongly suffering-focused view, the destruction of all life could be desired. We will expand on this later. Note: Estimating the welfare of wild animals is an ongoing scientific problem and there is insufficient evidence to conclude that all or even most animals are having net-negative lives as argued by Michael Plant here.

Furthermore, if you are instead assuming a symmetric view (i.e. one unit of negative experience has the same moral importance as one unit of positive experience), you have to extrapolate whether you expect our descendants to create more value or disvalue in the future. If you come to the conclusion that humans are creating more disvalue (e.g. going to spread wild animal suffering to other planets or create suffering digital tools), you may still argue that the total extinction of all life is positive.

Human Extinction

Global Catastrophic Bilogical Risk (GCBR) is the most straightforward cause of extinction: A dangerous pathogen kills 99.999% of all humans and the remaining humans can never restore civilization and are devastated by a natural disaster or other causes. Similarly, extreme climate change, extreme asteroid impacts and extreme nuclear winter through nuclear war could lead to human extinction. However, in each of these cases, it seems likely that sentient life will persist (e.g. fish in the sea, birds in the arctic, small crustaceans). Thus, the value of a future with human extinction but the perseverance of other sentient life is determined by the wellbeing of wild animals which may be negative on average.

It might also be possible that a new civilization-building species appears once humanity goes extinct (either from outside earth or from earth itself). Including this in our estimates adds uncertainty since it is not at all clear whether this new civilization would be creating more value or disvalue. We come back to this question in the section on Aliens.

Naively, it seems positive to reduce the chance of biorisk to a) prevent human extinction and b) to help wild animals or prevent them from being born. However, it is very unclear whether humans will ever help wild animals. As argued here, intervening actively in “nature” is highly controversial, especially in the environmentalist and conservationist movements.

It may even happen that humans spread wild animals to terraformed planets and thus ignorantly increase wild animal suffering even further. Though so far spacefare has tried to prevent spreading life to other planets. If you thought this was a likely outcome, preventing human extinction may be negative because it could lead to the spread of suffering on astronomical levels.

Furthermore, it has been argued that humans may accidentally create sentient tools, i.e. suffering subroutines, that might also lead to the spread of suffering on astronomical levels. This case remains speculative and even futures with suffering subroutines may be net-positive if many happy sentient beings exist as well.

Finally, the most severe case for why the extinction of humanity may be positive is if you expect humans to create misaligned AGI that runs simulations involving suffering beings or using suffering subroutines. Maybe this would be such a terrible future that humans going extinct now so they never create misaligned AI might be the lesser evil. See the later section on potentially very negative futures for more on this.

Extinction and Replacement

Due to instrumental convergence, some forms of misaligned Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) may try to harvest as much energy as possible, thus eventually block the sun, leading to the extinction of (sentient) life on earth. However, some forms of AI may themselves be sentient. Thus, our galaxy could contain value even after all sentient biological life is gone. It is very unclear how positive the experiences of AGI would be and whether or not it would replicate or create suffering sentient tools (more on this in the section on very negative futures).

From some suffering-focused views and maybe even from some more symmetrical views, non-conscious, misaligned AI ending all human and animal suffering may be a better future than the possibility of humans spreading suffering throughout the galaxy. Again, the value of extinction risk reduction from AI depends on what would counterfactually happen.

[redacted]’s Conclusion

I have tried to make the strongest case for why human extinction may be positive. All things considered, it seems like the expected value of the future is decided by the tail outcomes. I.e. even though these are very unlikely, they contain many orders of magnitude more value than average futures. This is because futures where [we have AGI and] AGI is explicitly optimizing for value lead to astronomical amounts of value while futures where AGI is not explicitly optimizing for it will just lead to comparatively small amounts of value or disvalue. On the other end of the spectrum AGI explicitly optimizing for disvalue would result in astronomical amounts of disvalue that dwarf worlds where humans create suffering on a much smaller scale (i.e. by spreading wild animal suffering).

Since I find it very hard to imagine a world where AGI is explicitly optimizing for disvalue, these outcomes seem much less likely than outcomes where AGI explicitly optimizes for value. I thus think that humans will in expectancy probably create more value than disvalue and it is thus positive to reduce extinction risk. I remain uncertain of this since the probability of us creating misaligned AGI may be higher than for the average species. If this were true, aliens or post-extinction earth-born species colonizing the universe would be a better outcome and thus human extinction would be desirable.

II. A case for “suffering-leaning ethics”

by Aaron

Introduction and motivation

To my understanding, “the expected value of extinction risk reduction is positive” means and can be rephrased as “all else equal, we should expect reducing the risk of human extinction to have morally good consequences, whatever those might be.” Of course, “whatever those might be” leaves much to be desired. I am taking as given that consequences are morally relevant if and only if they matter for the wellbeing of sentient entities; I expect few, if any, self-described consequentialist effective altruists will object.

More contentiously, the following argument is phrased in terms of and therefore implicitly takes hedonic utilitarianism as given. That is, I assume that pleasure is the sole moral good and suffering the sole bad, though I often substitute “happiness” for “pleasure” because of its broader and more neutral connotation.

That said, I am very confident (95%) that the argument is robust to different understanding of “wellbeing” represented in the EA community, such as a belief in the goodness of non-hedonic “flourishing” or life satisfaction as distinct from hedonic pleasure. Negative utilitarians, who believe it is never morally acceptable to increase the total amount of suffering, may agree with some of my reasoning but are unlikely to find the argument compelling at large.

Why I do not find one argument for the in-principle moral “justifiability” of any amount of suffering convincing

In Defending One-Dimensional Ethics, Holden Karnofsky argues that “for a low enough probability, it’s worth a risk of something arbitrarily horrible for a modest benefit.” Under standard utilitarian assumptions, we can multiply each side of this “equation” quoted above by a large number[1] and derive the corollary that a world with arbitrarily high disvalue (suffering) can be made net-positive with some arbitrarily high amount of value (happiness).

Upon first reading Karnofsky’s post, I acknowledged (grudgingly) that the argument was sound. My limited biological brain with its evolution-borne intuitions just wasn’t up to the task of reasoning about unfathomably-large hedonic quantities, I assumed, and a wiser, more rational being would see that the claim in bold above is true.

I’ve since changed my mind and this post explains why. More precisely, I will argue for the following thesis:

Under a form of utilitarianism that places happiness and suffering on the same moral axis and allows that the former can be traded off against the latter, one might nevertheless conclude that some instantiations[2] of suffering cannot be offset or justified by even an arbitrarily large amount of wellbeing.

Defending this thesis and critiquing the previous claim

As a simple matter of preference, it seems that humans are generally[3] willing to trade some amount of pain for some ‘larger’ amount of pleasure, all else equal.[4] Nonetheless, there are some amounts of suffering that I would not accept in exchange for any amount of happiness, and, I believe, many besides me share this preference. In one sense, such preferences are just that – preferences, or descriptions of how a person behaves or expects they would behave in the relevant circumstances.

For myself and I believe many others, though, I think these “preferences” are in another sense a stronger claim about the hypothetical preferences of some idealized, maximally rational self-interested agent. This hypothetical being’s sole goal is to maximize the moral value corresponding to his own valence. He has perfect knowledge of his own experience and suffers from no cognitive biases. You can’t give him a drug to make him “want” to be tortured, and he must contend with no pesky vestigial evolutionary instincts.

Those us who endorse this stronger claim will find that, by construction, this agent’s preferences are identical to at least one of the following (depending on your metaethics):

One’s own preferences or idealized preferences

What is morally good, all else equal

For instance, if I declare that “I’d like to jump into the cold lake in order to swim with my friends,” I am claiming that this hypothetical agent would make the same choice. And when I say that there is no amount of happiness you could offer me in exchange for a week of torture, I am likewise claiming this agent would agree with me.

To be clear, I am arguing neither that my expression of such a preference makes it such that the agent would agree, nor that his preference is defined as my own, nor that my preference is defined as his.

Rather, there are at least two ways my preference and this agent’s might diverge. First, I might not endorse my de facto preference as the egotistically rational thing to do. For instance, I could refuse to jump in the lake in spite of my own higher-order belief that it is in my own hedonic interest to. Second, I might be mistaken about what this agent’s choice would be. For instance, perhaps the lake is so cold that the pain of jumping in is of greater moral importance than any happiness I obtain.

To reiterate, I, and I strongly suspect many others, believe that this egoistic being would indeed refuse a week of hideous torture even in exchange for an arbitrarily large hedonic reward, which might even last far longer than a human lifespan.

Formal Argument

We can formalize the argument I’ve been developing as follows:[5]

(Premise) One of the following three things is true:

(1) One would not accept a week of the worst torture conceptually possible in exchange for an arbitrarily large amount of happiness for an arbitrarily long time.[6]

(2) One would not accept such a trade, but believes that a perfectly rational, self-interested hedonist would accept it; further this belief is predicated on the existence of compelling arguments in favor of the following:

Proposition (i): any finite amount of harm can be “offset” or morally justified by some arbitrarily large amount of wellbeing.

(3) One would accept such a trade, and further this belief is predicated on the existence of compelling arguments in favor of proposition (i).

(Premise) In the absence of compelling arguments for proposition (i), one should defer to one’s intuition that some large amounts of harm cannot be morally justified.

(Premise) There exist no compelling arguments for proposition (i).

(Conclusion) Therefore, one should believe that some large amounts of harm cannot be ethically outweighed by any amount of happiness.

Defending Premise 3

Here, I will present evidence that there exists no compelling argument that any finite harm can in principle be justified by a large enough benefit (i.e., proposition (i)). Of course, this evidence is inherently inconclusive, as it isn’t possible to show that something doesn’t exist. I encourage readers to link or describe proposed counterexamples in the comments. Nonetheless, I will argue that one popular argument which seems to show proposition (i) to be true is fundamentally flawed.

Karnofsky’s post Defending One-Dimensional Ethics is the most complete, layperson-accessible defense of such a position that I am aware of. It is also particularly conducive to my critique because of his conclusion that “for a low enough probability, it’s worth a risk of something arbitrarily horrible for a modest benefit,” which seems ethically equivalent to the claim that “for a large enough benefit, it’s worth something arbitrarily horrible.” Karnofsky’s argument consists of a series of compelling premises and subsequent intermediate steps–each of which seems intuitively correct, logically sound, and morally correct on its own–leading to this non-obvious conclusion.

Fundamentally, however, the post errs by employing the example of “a 1 in 100 million chance of [a person] dying senselessly in [the] prime of their life” as an accurate, appropriate illustrative example of the more general “extremely small risk of a very large, tragic cost.” On the contrary, an unwanted death seems to me (1) the removal of something good rather than the instantiation of suffering[7] and (2) qualitatively less severe (and quantitatively smaller in magnitude, if you prefer) than other conceivable examples of a “large, tragic cost.”

To his credit, Karnofsky anticipates this second objection and includes a brief consideration and rebuttal in his dialogue:

[Utilitarian Holden]

...for a low enough probability, it’s worth a risk of something arbitrarily horrible for a modest benefit.

[non-Utilitarian Holden]

Arbitrarily horrible? What about being tortured to death?

[Utilitarian Holden]

I mean, you could get kidnapped off the street and tortured to death, and there are lots of things to reduce the risk of that that you could do and are probably not doing. So: no matter how bad something is, I think you’d correctly take some small (not even astronomically small) risk of it for some modest benefit. And that, plus the “win-win” principle, leads to the point I’ve been arguing.

On the object level, it seems plausible to me that there might be no action that those like myself and some readers, fortunate to live in safe geographical area during the safest part of human history, could take to (prospectively) reduce the risk of being tortured to death, because the baseline probability is so low. Further, an altruist might rationally accept some personal risk in exchange for reducing the risk of this outcome to others.

But this all seems beside the point, because we humans are biological creatures forged by evolution who are demonstrably poor at reasoning about astronomically good or bad outcomes and very small probabilities. Even if we stipulate that, say, walking to the grocery store increases ones’ risk of being tortured and there exists a viable alternative, the fact that a person chooses to make this excursion seems like only very weak evidence that such a choice is rational.

I concede that (under the above stipulations) the conclusion “a rational hedonist would never walk to the store” seems counterintuitive, but it does not seem to me any more counterintuitive than some of the implications of a truly impartial total utilitarianism (which largely run through strong longtermism). In the post, Karnofsky convincingly shows that a small benefit to sufficiently many people may justify a small risk of death. In fact, I even think a (different) modified version of the argument convincingly shows the same to be true for a more tolerable amount of suffering.

But, as far as we know, there’s no law written in the fabric of the universe or in the annals of The Philosophical Review stating that an arbitrarily small probability of terrible suffering is morally equivalent to a more certain amount of a lesser evil, or that the torture of one is ethically interchangeable with papercuts for a trillion.

Affirmative argument against proposition (i)

To rephrase that more technically, the moral value of hedonic states may not be well-modeled by the finite real numbers, which many utilitarians seem to implicitly take as inherently or obviously true. In other words, that is, we have no affirmative reason to believe that every conceivable amount of suffering or pleasure is ethically congruent to some real finite number, such as −2 for a papercut or −2B for a week of torture.

While two states of the world must be ordinally comparable, and thus representable by a utility function, to the best of my knowledge there is no logical or mathematical argument that “units” of utility exist in some meaningful way and thus imply that the ordinal utility function representing total hedonic utilitarianism is just a mathematical rephrasing of cardinal, finite “amounts” of utility.

Absence of evidence may be evidence of absence in this case, but it certainly isn’t proof. Perhaps hedonic states really are cardinally representable, with each state of the world being placed somewhere on the number line of units of moral value; I wouldn’t be shocked. But if God descends tomorrow to reveal that it is, we would all be learning something new.

While far from necessary for my argument, it may be worth noting that an ethical system unconstrained by the grade-school number line may still correspond, rigorously and accurately, to some other mathematical model.

One such relatively simple example might be a function mapping some amount of suffering (which we can plot on the x-axis of a simple cartesian plane) to an amount of happiness whose moral value is of the same magnitude (on the y axis); that is, the “indifference curve” of a self-interested rational hedonist. Though “default” total utilitarian views seem to imply that such a function’s domain must be the entire set of non-negative real numbers, it is easy enough to construct a function with a vertical asymptote instead.[8]

The place of ethics in our argument

Assigning (some amounts) of suffering greater ethical value does not necessarily make human extinction more preferable. One might believe, for instance, that humanity will alleviate suffering throughout the rest of the universe, should it continue to survive.[9]

However, enabling such “cosmic rescue missions” hardly seem the motivation for or reasoning behind longtermism-motivated extinction reduction projects. We should be skeptical, indeed, that spreading humanity or post-humanity throughout the universe would lead to a reduction in the amount of “unjustifiable” (in the sense I’ve been describing) suffering.

If this is so, it could render actions to reduce the risk of human extinction per se morally indefensible. And if humans’ continued existence really can be expected to alleviate such large amounts of suffering, this should be affirmatively made.

Important Considerations for Estimating the Value of the Future

The Value of Today’s World

An estimation on the value of today’s world can tell us whether the extinction of all life on earth will be positive or negative for person-affecting views. Grey goo, asteroid impact, and attack from aliens are some ways all life on earth could end. Today’s hedonic value is probably dominated by wild animals as they vastly outnumber humans, farmed animals, lab animals, and pets combined. Quite some people in the EA community believe wild animals are likely to have negative lives due to disease, predation, thirst, hunger, short lifes, and many offsprings dying before reaching maturity. Nonetheless, there are some disagreements due to anthropomorphizing of animals, death from predation lasting for a short time compared to lifespan for k-selected species, and the lack of a good objective measure of valence intensity. Despite that, if the average life of wild animals were only slightly negative, the current value of the world would be highly negative due to the sheer numbers of wild animals on earth.

Comparing the scale of animal welfare to human welfare shows that the comparative weighted population of animals is estimated to be 15K − 5.2M times larger than the human population and the required human population for 50⁄50 split in expected welfare is between 120T − 4.3 x 1016 people. The previous comparisons takes welfare credence and moral weight into account. Welfare credence discounts for the likelihood of sentience as produced by Rethink Priorities. Moral weight discounts for the plausibly diminished amount of pain and pleasure felt by the animal. As the human population is expected to stabilize in the next 70 years at 11B people, without transformative technologies (e.g. AGI) human welfare may never dominate animal welfare. Since extinction of all life will reduce suffering for so many non-human lives, the expected value of extinction of all lives will be highly positive unless suffering is immensely reduced (e.g. wild animal populations massively decline) or happiness is vastly increased (e.g. humans or transhumans have extreme population growth probably due to ability to create digital people). This may mean if we live in a simulation that is expected to end before digital sentient beings can be created cheaply, animal welfare could be the most important cause area.

In cases where only humans go extinct, humanity’s net impact on wild-animal suffering will dominate the value of extinction risk reduction for person-affecting views and may help to predict whether the future will be positive. An estimate showed that the invertebrate population could have declined by 45% over the past 40 years. Assuming a conservative estimate of 10% decline and current estimate of ~1018 insects, would mean humans avert 1017 insects per year. Hence, the average person on Earth was estimated to prevent ~1.4x107 insect-years through their environmental impact each year. Thus, the net impact of humanity is likely positive. This will significantly increase the expected person-affecting value of extinction risk reduction done by Gregory Lewis. Nevertheless, if invertebrates are not considered, it’s unclear whether sentience-weighted global animal population has on balance decreased due to humanity’s existence. The estimates in this paragraph have high uncertainty due to possible methodological issues, which warrants further investigation to validate the net impact of humanity on wild-animal suffering.

Some might think suffering of farm animals may outweigh suffering of wild animals. Nonetheless, the weighted animal welfare index by Charity Entrepreneurship shows that wild animal populations vastly exceed farm animal and farm animals don’t suffer enough to be comparable to wild animals. However, the welfare score was limited to a minimum of −100 and a maximum of 100, which could be significant since it may be possible to create a digital sentient with much higher or lower welfare. Additionally, it is unclear whether reducing animal consumption has a net positive or negative effect on animal suffering, since increasing farm animals reduces wild animals. This implies that humane slaughter is better than veg outreach to reduce animal suffering and more disvalue comes from wild animals rather than farm animals. Furthermore, eating beef and dairy plausibly have a net positive effect on animal welfare. This could lead to the conclusion that increasing dairy and humanely slaughtered beef consumption as being a possible way of increasing expected value of the future.

Some other reasons humanity’s actions are net negative could come from ecological damages and retributivism. Though, the value of ecology itself needs to outweigh the wild animal suffering in it for the value of ecology to be positive. In the case of retributivism, where it was argued that humanity should go extinct as punishment due to atrocities such as the Holocaust, slavery, and the World Wars. Considering the massive amount of wild animal suffering caused by other wild animals, humanity could have a duty to cause the extinction of all lives on earth. It is unclear whether humanity should to make sure all lives are exterminate to prevent repopulation of earth, since retributivism may not apply to future crimes. However, assuming aliens exist and are likely to cause extinction worthy atrocities, our duty may be to hunt down aliens instead.

Possible Negative Futures

When looking at the expected value of extinction risk reduction, we need to consider the possible ways in which the future could potentially be extremely bad, and we also believe that there is no need to assume a suffering focused view in order to conclude that the future has an alarming number of scenarios in which it could be net negative.

Animals and Cosmic Rescue Missions

A popular argument made in favor of extinction risk reduction is that of cosmic rescue missions

– the possible future ability of humans (or posthumans) traveling to other plants to alleviate any suffering out there – as a moral imperative. Brian Tomasik, however, argues that humans may in fact spread suffering to other planets by bringing along wild animals which we know are sentient(as opposed to lifeforms on other planets). It’s uncertain that the kind of conscious suffering found on Earth would be found on other planets, as Tomasik writes “Most likely ETs would be bacteria, plants, etc., and even if they’re intelligent, they might be intelligent in the way robots are without having emotions of the sort that we care very much about. (However, if they were very sophisticated, it would be relatively unlikely that we would not consider them conscious.)”. So this would also lead us to update in the direction that we would increase suffering by going to other planets.

If humans are able to colonize space they may also spread extremely large numbers of wild animals to other planets (such as Mars) to aid in terraforming. Given the approximate number of wild animals on Earth and the likelihood that their lives are net negative given all the starvation, disease, parasites and predation in nature (the arguments for this are out of scope but see here as a starter), terraforming other planets could result in massive amounts of new suffering, and that is without taking into consideration the planets after terraforming is complete.

Digital Sentience

Post-humans or AGI may run digital simulations composed of digital sentience for a variety of reasons. For example, scientists could run billion year simulations of evolution on different planets with various atmospheric make-ups to understand the process of terraforming. The beings in the simulations may well be sentient. If this is the case then these simulations could be the source of enormous amounts of suffering, and possibly one of the main sources in the future given future processing power.

Simulations could also be used for much more trivial purposes such as entertainment. Many humans today enjoy pastimes which have violence as a major theme such as video games, movies & TV shows. Whilst these pastimes can be considered harmless now, if in the future we have simulations capable of suffering and we do not reach a widespread moral consideration for these digital beings then we risk inflicting massive amounts of unintended suffering purely for entertainment and social purposes.

Furthermore, future computing with advanced forms of AI may involve sophisticated tools with the capability to suffer, this could go unrecognized and lead to vast amounts of suffering on a galactic time span. Future processing power will also allow post-humans to run vast numbers of simulations which could lead to digital suffering outweighing all other forms in the future.

Cause X

You’ve likely heard about ‘Cause X’. It’s the idea that there may be a highly pressing cause area (‘X’) which we have yet to discover. There is an adjacent idea to consider for future suffering – Black Swans. We can discuss and imagine possible ways the future could be bad (as done above), but we can only imagine so much. The future is extremely vast and there could be many possible large s-risks we haven’t thought of. If you are convinced that preventing suffering is a greater priority than increasing happiness then black swan scenarios should be given more weight than the many possible unknown positive futures.

Authoritarian Lock In

There is no guarantee that the present day trend of democratization will continue into the future. There’s a chance that an authoritarian state wins an arms race in the future, which would drastically change the balance of power in their favor. An example for this case could be if a rogue state is able to create aligned AGI before their competitors. The world could then devolve into an authoritarian dystopia with no realistic paths to improvement. We can expect surveillance capabilities to be much improved with AGI, given that even AI of today has led to improved surveillance capabilities of the populations in certain states. The negative effects of these dystopias vary widely based on the negative traits they may end up having. For example, these societies may have moral blindspots to certain groups and as there is likely to be fewer opportunities to change course once an authoritarian state achieves hegemony, these moral blindspots could be perpetuated for as long as the society survives, again leading to huge amounts of suffering.

Aliens

According to this post on grabby aliens under some assumptions (though not under others) it is likely that we will encounter aliens in the future (though not in the next millennia). Thus, if we survive the precipice and colonize other stars, we will just transform parts of the universe that would have been transformed by aliens later. To update on this accordingly, we need to estimate whether humans are more or less likely to convert matter into positive (negative) value than other civilizations. Furthermore, we have to account for the fact that there might be conflicts between different civilizations if their values do not align. If you believe humans are likely to act less ethical than the average alien species or you think that conflicts would decrease the future’s value so much that it would be better for humans not to start colonizing space, you should update against extinction risk reduction. (E.g. because encountering aliens involves blackmail with massive suffering in simulations)

To quote A longtermist critique of “The value of extinction risk reduction is positive”:

On the side of optimism about humans relative to aliens, our species has historically displayed a capacity to extend moral consideration from tribes to other humans more broadly, and partly to other animals. Pessimistic lines of evidence include the exponential growth of factory farming, genocides of the 19th and 20th centuries, and humans’ unique degree of proactive aggression among primates (Wrangham, 2019).[52] Our great uncertainty arguably warrants focusing on increasing the quality of future lives conditional on their existence, rather than influencing the probability of extinction in either direction.

Aliens could be an extinction risk in the future since the best move to make if a spacefaring civilization discovers another spacefaring civilization may be to wipe out the other civilization. The reasons for this are that they may not be able to tell if the other civilization is peaceful or malevolent, invasion fleets becoming obsolete due to the long time required to reach other civilization, and space faring civilizations having enough energy to send multiple world ending strikes against every planet it suspects of harboring life. This assumes almost all civilizations live on planets, so having self-sustaining spaceships could reduce extinction risk from alien attacks. If we expect to encounter many advanced alien civilizations, we should expect life from earth to have a higher chance of extinction. Furthermore, some might worry that wars between advanced civilizations could cause extreme amounts of suffering. Nonetheless, if we expect wars between advanced civilizations to end in quick extinction strikes, the suffering due to this will be low. Even if we do encounter sadistic aliens with exceptional defensive measures, we may opt for self-extinction to reduce suffering. In case we found ourselves in a dystopia lock in, looking for aliens could be a way to cause self–extinction with a possibility of cosmic rescue from aliens.

Cosmic Rescues

As argued in A longtermist critique of “The expected value of extinction risk reduction is positive”, the likely existence of wild animal suffering or unknown sources of suffering on other planets should update you in favor of reducing extinction risk. However, this could be outweighed by the chance that we will create suffering.

What Are We Missing?

Much like ‘Cause X’, predicting future problems is extremely challenging, if not impossible. We have a stronger sense of current day sources of suffering (ex. the mistreatment of animals) and generally believe they continue to cause suffering in the future as long as they exist. However, there potentially are unknown sources of suffering that we are missing that might produce a lot of suffering. It’s really hard to imagine and predict. We should continuously look to prevent this possible large-scale future suffering. If there is a high risk of an unknown astronomical s-risk developing, and you believe in negative utilitarianism (that preventing suffering is key), then this further complicates the evaluation of ERR.

Additionally, human’s might unintentionally create a significant amount of suffering from our lifestyle and choices, as we have done with the animal industry. Human’s use of animals for consumption and labor is causing unimaginable amounts of suffering. Industrialization and the development of factory farms over the past 100 or so years has multiplied the number of animals killed – many of which are born just to be killed. This suffering was likely unimaginable to people 100 years ago. Furthermore, a list of open research questions by Jason Schukraft could help determine the differences in the intensity of valenced experience across species.

It’s hard to imagine what future social norms and technologies might develop and which ones might lead to a moral catastrophe. However, human-caused animal suffering shows us that extreme s-risks from human social actions is an ongoing problem and possibility that we should be mindful of. At the same time, the argument loops in that there might be tons of suffering in the universe (caused by non-human animals, other beings, or even nature) that we have a moral obligation to get rid of. This would mean that human existence is needed for reducing s-risks; while at the same time, if you take a suffering-reduction lens, we also need to make sure humans aren’t causing a Black Swan suffering event.

We did not discuss much about how the simulation argument affects the value of ERR. Related research was done by Center on Long-Term Risk, but further research may be valuable. More research could be done on whether we should have the option to bring about our own extinction and extinction of all life from earth and who gets to make this decision in order to reduce suffering. Moreover, predicting how we might interact with advanced alien civilizations could be a crucial consideration for whether ERR is positive.

Closing thoughts

Personal Epistemic Beliefs—Is ERR Positive?

ES − 85%, Why? While there’s definitely uncertainties, i’m more convinced it’s still positive

Aaron -

30% that “pushing a hypothetical button that reduces the risk of extinction per se and changes nothing else has positive expected value.”

75% that “given the world we live in, actions taken specifically to reduce the risk of extinction, when considered together as one a single block , has positive EV.” and so does all such actions considered together as a unit.”

Most of the 70% probability mass runs through through AI alignment, which also reduces the risk of s-risk.

It also seems likely that most extinction reduction programs would also reduce the risk of a recoverable societal collapse. I tentatively think such an outcome would be bad, in large part because it would leave us worse off the second time around.

Jac − 55% assuming classical utilitarian

Hasan − 50%

[redacted] - Reducing extinction from AI: 95% Reducing other causes of extinction: 75% (I think you need to extrapolate if we solve alignment and I’m extremely uncertain about the likelihood of this) [note that I’m not well calibrated yet]

Final notes from the authors

This was fun but very challenging to write, and doings so caused all of us to learn and to grow.

We’re also a group of five people with different thoughts and takeaways from the reading. So we wanted to share our personal beliefs on the topic. In the interests of reasoning transparency, we’d like to note that many of us hadn’t tackled the topics covered in this piece before the past month so please take our conclusions with a grain of salt and we encourage readers to leave any constructive comments and feedback. We also encourage you to share your own thoughts on whether ERR is positive like we did in the comments.

ES

Red-teaming this paper was certainly tough (for me, ES, at least) and I definitely have more knowledge and awareness of moral principles than I did before. To me, the main takeaway is to not assume ERR is positive and beneficial but we need to work through the uncertainties and have an awareness of its negative implications in order to form better views.

Aaron

Over the course of this project, I gradually came to believe (~85%) that the question of the value of ERR, which more literalist readers (like myself) might take to mean

Should we turn down the magic dial which controls the probability that all humans drop dead tomorrow?”

is not merely different from but in practice essentially unrelated to the more action-relevant question of

Given the world we live in, should act to reduce the likelihood that there are no humans or post-humans alive in, say, 10,000 years (or virtually any other time frame)?

This is true for what seem like pretty contingent reasons. Namely, most of the risk of human extinction runs through

Unaligned AI, which can be thought of as an agent in its own right and a net-negative one at that, and

Biological pathogens, against which (it seems to me, though I am uncertain) most interventions aimed at preventing extinction per se would also (and plausibly to an even greater degree) prevent societal breakdown, conflict, and impaired coordination.

That said, there are of course “all or nothing” sources of extinction risk—such as large asteroid impact or “stellar explosions”—that more closely resemble the “all humans drop dead tomorrow” scenario from above.[10] And, indeed, reducing the risk of these catastrophes seems essentially equivalent to reducing the risk of extinction “all else equal.”

Naively take my probabilities I offered above (30% that ERR is good all else equal in theory, 75% that it is good in practice) and (conveniently) assume away any correlation, we get a 52.5% chance that acting to prevent these “all or nothing” extinction events is bad, but acting to prevent misaligned AI and (less certainly, and probably to a lesser extent), biorisk is good.

Fortunately, accepting this conclusion doesn’t seem to imply much change to the actions of the longtermist community in mid-2022.

But that could change if, say, we discover how to create AGI in such a way that it no longer threatens to cause suffering or harm other beings in the universes but nonetheless remains an extinction threat. Less speculatively, this very tentative conclusion suggest that any peripheral efforts to, for instance, prevent a supervolcano eruption may be a poor use of resources if not actively harmful.

Finally, I’d highlight two research programs that seem to me very important:

Unpacking which particular biorisk prevention activities seem robust to a set of plausible empirical and ethical assumptions and which do not; and

Seeking to identify any AI alignment research programs that would reduce s-risks by a greater magnitude than “mainstream” x-risk-oriented alignment research.

Acknowledgements

We’d like to give a special thanks to Vasco Grilo, Cillian Crosson, and Simon Holm for constructive feedback on our writing.

Further Reading & Resources

A longtermist critique of “The expected value of extinction risk reduction is positive” – Anthony DiGiovanni

Arguments for Why Preventing Human Extinction is Wrong – Anthony Fleming

Would Human Extinction be Good or Bad? – Michael Dello-Iacovo

Risks of Astronomical Future Suffering – Brian Tomasik

How Good or Bad Is the Life of an Insect – Simon Knuttson

A Typology of S-Risks – Tobias Baumann

Against Wishful Thinking – Brian Tomasik

- ^

More specifically, the quantity if refers to the probability of the terrible event.

- ^

I am intentionally avoiding words like “amount” or “quantity” here

- ^

Or would be, given the opportunity.

- ^

I considered supporting this claim with empirical psychological or economic literature. However, a few factors contributed to my decision not to:

The failure of many papers in the relevant subfields to replicate;

The author’s and a reviewer’s intuitions that the claim is very likely to be correct and unlikely to be challenged; and

An abundance of simple, common sense examples, such as humans’ general willingness to:

Wait in line for something we want

Take foul-tasting medications

Study for tests

Eat spicy food

- ^

This can be modeled as follows, where:

an ideally rational egoistic hedonist would not accept the trade described.

Proposition (i): any finite amount of harm can be “offset” or morally justified by some arbitrarily large amount of wellbeing.

there exists a compelling argument for proposition (i).

- ^

even if this entails setting aside speculative empirical constraints such as the amount of energy in the universe).

- ^

One might reasonably object that there is no fundamental moral or ontological difference between the removal of a good and creation of a bad. I believe, however, that the second consideration (if one accepts it) suffices to show that a single unwanted death is at least plausibly too small in magnitude to serve as a general example of a “very large and tragic cost.”

- ^

Because there are no well-defined “units” of happiness and suffering, the curve on the left (which increases in slope with suffering) could instead be shown as a straight line of constant slope. The key distinction is that the right curve alone has a vertical asymptote.

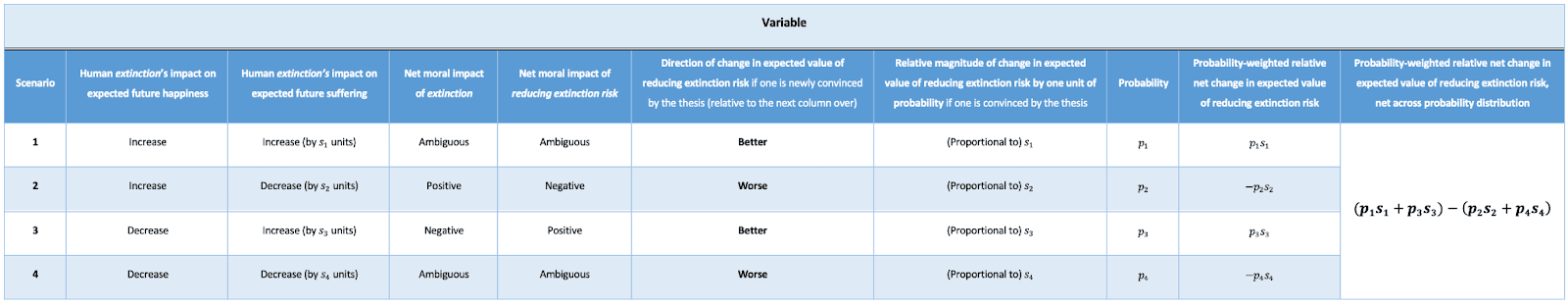

- ^

As shown in the middle bolded column of the table below, moving towards suffering focused ethics should lead one to believe that reducing extinction is better than previously thought in scenarios 1 and 3, and worse in 2 and 4. The final, rightmost column presents term a term whose sign specifies whether the argument makes the value of preventing extinction better (if positive) or worse (if negative), relative to a less suffering-focused perspective.

In aggregate, this term can be understood as the expected effect of human extinction on unjustifiable suffering, setting aside any impact on wellbeing.

- ^

One unifying characteristic of these might be “physical destruction of a significant portion of Earth.”

On the “bad futures to do with aliens” thing, here are some potential bad futures which extinction risk mitigation makes more likely:

humans get enslaved by / are oppressed by aliens

humans enslave / oppress aliens

humans cause extinction of an alien civilisation, which due to some aspect of their alien biology could have generated more utility than humans ever could

technologically advanced humans create something which accidentally or intentionally kills every alien civilisation in the universe (GCBR, nuclear war and climate change mitigation make this more likely but AI risk mitigation makes this less likely)

I think we also have historical precedent for the first 3 from European colonialism.

Yeah, I think this is pretty plausible at least for sufficiently horrible forms of suffering (and probably all forms, upon reflection on how bad the alternative moral views are IMO). I doubt my common sense intuitions about bundles of happiness and suffering can properly empathize, in my state of current comfort, with the suffering-moments.

But given you said the point above, I’m a bit surprised you also said this:

What about “(4): One would accept such a trade, but believes that a perfectly rational, self-interested hedonist would not accept it”?

Yeah...I think I just forgot to add that? Although it seems the least (empirically) likely of the four possibilities

Last week there was a post on “The Future Might Not Be So Great” that made similar points as this post.

I’m excited about people thinking about this topic. It’s a pretty crucial assumption in the “EA longtermist space”, and relatively underexplored.

Oh man, that’s really bad on our part. Thanks for the correction. Apologies to Friederike for this.

Looks like there’s a formatting bug with pictures in the footnotes. The bottom picture was intended to be placed in footnote 5.