Longtermism and alternative proteins

I spoke at EA Global London 2023 about longtermism and alternative proteins. Here’s the basic argument:

1) Meat production is a significant contributor to climate change, other environmental harms (pretty much all of them), food insecurity, antibiotic resistance, and pandemic risk—causing significant and immediate harm to billions of people.

2) All of these harms are likely to double in adverse impact (or more) by 2050 unless alternative proteins succeed. [EDIT for clarity: This is due to a doubling of animal agriculture that is extremely likely unless alt proteins succeed.]

3) Their X risk level is sufficiently high (Ord chart) that they warrant attention from longtermists. Especially for longtermists in policy or philanthropy, adding alt proteins to the portfolio impactful and tractable interventions that you support can allow you to do even more good in the world (a lot of it fairly immediate).

In the talk, I cite this report from the Center for Strategic & International Studies’ director of global food security & director of climate and energy, as well as a report from ClimateWorks Foundation & the Global Methane Hub (1-pager w/r/t the points I made in the talk here).

Below are the recording and transcript—comments welcomed.

Here’s a link to the slides from this talk.

Introduction

The observation is that we have been making meat in the same way for 12,000 years. Food is a technology. Making meat is a technology. The way we do it now is extraordinarily inefficient and comes with significant external costs that do indeed jeopardize our long-term future. This is Johan Rockström after the EAT-Lancet Commission called on the world to eat 90 percent less meat back in 2018 and 2019. He said, “Humanity now poses a threat to the stability of the planet. This requires nothing less than a new global agricultural revolution.” That’s what I’m going to be talking about, and I’m going to situate it in terms of effective altruism.

There are five parts to the talk. The first one is that meat production has risen inexorably for many decades, and there is no sign of that growth slowing. The second is that our only strategy for changing this trajectory is support for alternative proteins—there’s not a tractable plan B. The third point is that alternative proteins address multiple risks to long-term flourishing and they should be a priority for longtermists. I’m not going to try to convince you they should be the priority or that they’re on par with AI risk or bioengineered pandemics. But I am going to try to convince you that unless you are working for an organization that is focused on one thing, you should add alternative proteins to your portfolio if you are focused on longtermism. Fourth, I want to give you a sense of how GFI thinks about prioritization so that what we’re doing as we expand is the highest marginal possible impact. Then we’ll have some time for a discussion which Sim will lead us through.

Meat Production has risen by 300% since 1961.

The first observation is that, since 1961, global meat production has risen 300 percent.

In China, it has skyrocketed by 1,500 percent. It’s 15 times up since 1961, and meat production and consumption is going to continue to rise through 2050.

There have been 11 peer-review articles looking at what meat production and consumption are going to look like in 2050. The lowest production is 61 percent more. One of the predictions is 3.4 times as much, so 340 percent more. Most of the predictions hover at about double. Most of that growth is not in developed economies. Developed economies have leveled off. They’re going up a little bit. Most of that growth is in developing economies and in Asia.

The world doesn’t have tractable solutions to this. Bill Gates when he released How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, on his book tour was talking about how the climate world has basically thrown up its hands on agriculture because the one strategy anybody was working on was trying to convince people to eat less or no meat, and that wasn’t working. That wasn’t even working in developed economies.

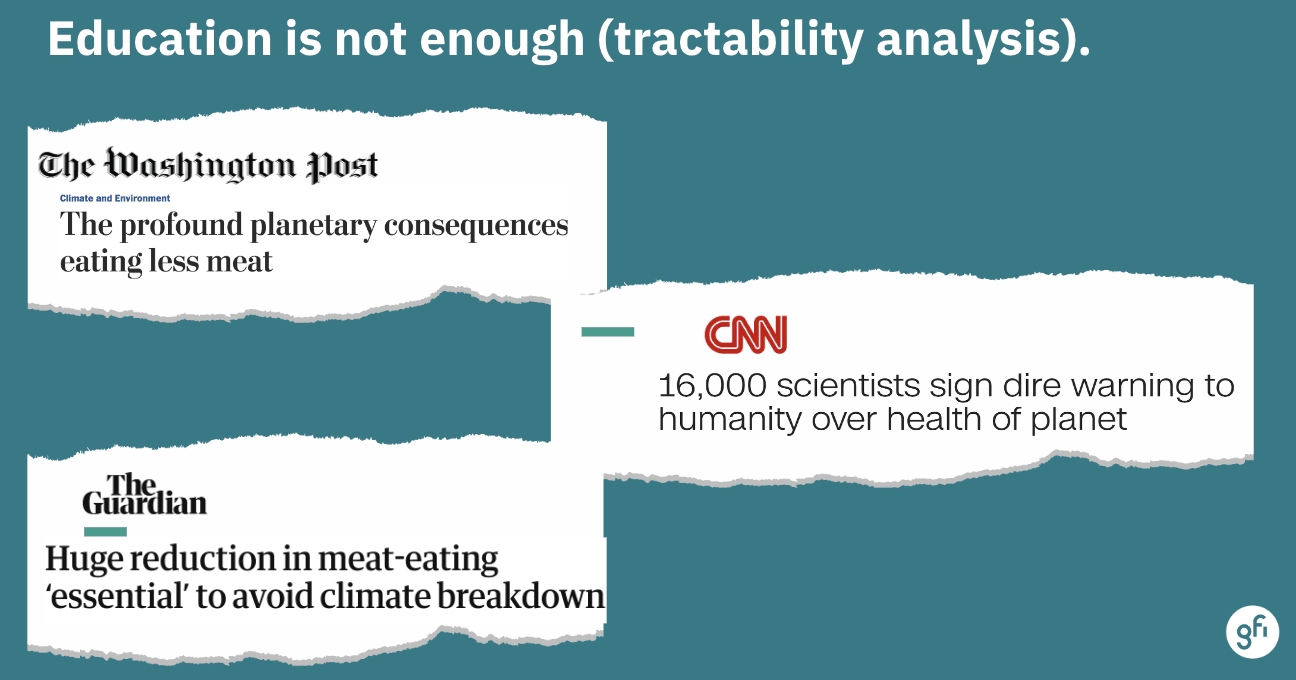

Education is not enough

We have been educating the world about the health consequences of meat consumption, the animal-protection consequences of meat consumption, and the environmental consequences of meat consumption. These are three articles about major peer-review studies about the environmental consequences of meat production in 2016, 2017, and 2018. Through that time, meat production even in the US, has continued to go up. In fact, no society in the history of the world has been more educated about the external costs of meat production than the United States right now. If you care about this issue at all, it’s impossible not to know about the adverse environmental consequences of meat production. And yet, in the US, the five highest years for per capita meat consumption are the most recent five.

Simply educating people about the harms of industrial meat production does not seem to be working. If it’s not even working in developed economies despite the best effort of many, many advocates and activists across global health, across the environment, across animal protection, it’s unlikely to work in the developing economies where basically what they’re trying to do is catch up with us in terms of protein consumption.

None of this is to say that education isn’t a good idea. We should be educating people. I started GFI as a result of education, the form of being educated about the external consequences of industrial animal production. The folks who started all of the formative companies in this space, and most of the scientists who are working on it changed their vocations because they learned about the harms of industrial meat production. But for the people on the ground, the consumers on the ground, the 10 billion people who are going to be here in 2050 where food choices are concerned, the vast majority of people simply don’t incorporate external costs into their food-production decisions.

GFI’s solution—“Alternative Proteins”

So what we need to do is, rather than convincing people to change their diets, we need to figure out how to create the meat that people love using plants or using cellular agriculture. Plant-based meat is not to convince people to pay more for something they don’t like as much. That’s not the goal of plant-based meat. The goal of plant-based meat is to recognize that meat is made of lipids, aminos, minerals, and water. Plants also have lipids, aminos, minerals, and water. We can apply food science to plants and figure out how to create the exact same meat experience using plants. And because it is so much more efficient as it scales up, we will be able to get to products that taste the same or better and cost the same or less.

That is GFI’s entire theory of change—the products need to taste the same or better and cost the same or less. Then you can quibble about whether that is necessary but not sufficient or whether the market can kick in and take it from there, just shoot us up the S-curve. But even if you think that is not sufficient, I would contend that that is absolutely necessary if we’re going to change the massive trajectory through 2050. We think this is the one solution to meat production that analogizes to renewable energy and electric vehicles.

So back to Bill Gates when he’s talking about how the climate community had thrown up its hands on agriculture. Basically, they just weren’t that excited about every other solution in food—nothing scales or feels tractable. Maybe you can do it at the city level. Maybe you can do it at the state level. Maybe you can do it at the national level, but if you tax meat at the national level or get the American Heart Association to spend $100 million telling people to eat less meat or whatever else, the impact of that is going to be contained to the area where the education happens or the area where the policy happens.

The awesome thing about renewable energy and electric vehicles and alternative proteins is that science in Singapore or Israel or Taiwan or Japan or Korea, science anywhere can scale everywhere. The other part of the analogy that’s true is that, with renewable energy, there’s an understanding through 2050, the world is going to consume more energy. One hundred percent of predictions, assuming the world continues to develop, the world will continue to consume more energy.

Part of the solution has to be more energy-efficient buildings. Part of the solution has to be educating people about their consumer choices to decrease individual energy consumption, but the solution to the problem of fossil fuels cannot be “convince people to consume less and energy efficiency” exclusively. We need something. We need to shift from fossil fuels to renewables. That’s a big part of the solution.

Similarly with electric vehicles, yes, we need more walkable cities. Yes, we need excellent public transportation. Yes, we should encourage people to ride bikes and walk, but inexorably more miles will be driven, and more cars will be sold through 2050.

Same thing with meat. Inexorably, yes, we should educate people about the health, environmental, and animal-protection consequences of meat eating. But globally we’re simply going to consume something on the order globally of twice as much meat by 2050, and the solution is to make that meat from plants and cultivate that meat from cells. It can’t just be what we’ve been trying for more than 50 years—tell people to eat less meat.

Impacts of a shift to alternative proteins

What are the impacts of a shift to alternative proteins assuming the theory of change works out? Climate change and land water use, basically between 93 and 99 percent less land, roughly 90 percent less direct emissions, 87 to 99 percent less water because you’re not growing crops to feed them to animals so that we can eat animals, which is a shockingly inefficient system.

There is now a scientific consensus that Paris climate goals are impossible unless meat consumption goes down. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says this explicitly in their last report, and they have no solutions for how you actually make that happen. The climate community broadly is pretty asleep at the wheel on this issue. They encourage diet change, but their heart is not in it because it hasn’t worked for 50 years, and it seems unlikely to start working now.

Food security is another really big issue, and this just makes intuitive sense. It takes, according to the World Resources Institute, 9 calories into a chicken to get 1 calorie back out. For pigs, it’s 11 calories. For cows, it’s 40 calories, and that means nine times the land, nine times the water, nine times the herbicides and pesticides, and it’s just a shockingly inefficient system.

I co-wrote this article for “Foreign Policy Magazine” in the fall about food security, and one of the anecdotes that my coauthor and I tell in this story is about how the UN Global Envoy on Food in 2008 called biofuel production a “crime against humanity.” The reason he called biofuel production a crime against humanity is that 100 million metric tons of corn and soy was being funneled into biofuels. It was driving up the price of cereals, and it was causing people to starve. That same year, 750 million metric tons of corn and soy were fed to chickens and pigs, and other farm animals. Exact same global relationship where food is concerned, by 2020, it was worth a billion metric tons of corn and wheat and another 270 million metric tons of soy, which were being fed to farm animals which were driving up the prices and leading to global starvation.

So climate change, biodiversity, food security, and antimicrobial resistance.

The U.K. government says the threat to the human race from antimicrobial resistance is more certain than the threat from climate change. About 70 percent of all of the medically relevant antibiotics produced by pharmaceuticals are fed to farm animals, not because they’re sick but to keep them alive in conditions that might otherwise be lethal. This is ushering an end to modern medicine. This is the former President of the World Health Organization, Margaret Chan saying, “The end of working antibiotics is essentially the end of modern medicine.” AMR is already killing 1.3 million people a year and supposed to be killing 10 million people a year by 2050.

And then finally, pandemic risk. The International Livestock Research Institute and the UN Environment Programme pulled together 13 of the leading zoonotic disease specialists in the world. They listed the seven most likely causes of the next pandemic. The first one is just more animals for food—increased demand for animal protein. These are direct quotes from their report. This isn’t my distillation or paraphrase. So increased demand for animal protein is the number one most likely cause of the next pandemic. Then they say, “unsustainable agricultural intensification,” but if you read the narrative, it has to do with genetic clone animals whose immune systems are depressed and then the way that the animals are treated, which makes the disease factories. In fact, animal agriculture is linked to six of seven of these. Somewhat ironically, the one that it’s not linked to is increased use and exploitation of wildlife, But the other six are linked to this massive increase in animal agriculture.

For longtermists, they’re listening to all of this, and they’re saying, “Yeah, that’s all bad, but that’s all short-termism. That’s not longtermism.” I would just remind folks that in Toby Ord’s book The Precipice he says, “Risks greater than 1 in 1,000 should be central global priorities.” I sort of nodded at this at the beginning [of this talk], but my goal is not going to be to convince you [that] if you’re working on unaligned AI or bioengineered pandemics (what are they − 1 in 10 and 1 in 30 existential risks) that this is something that you should do instead. But if you are working in policy (I think there’s a general consensus that where you get 100,000x impact is convincing governments to take these things seriously and launch programs focused on them), you can have a more diverse portfolio than unaligned AI and bioengineered pandemics. In fact, it’s probably to our benefit to have a more diverse portfolio. And I would contend that alternative proteins should be a part of that portfolio for all of the reasons that I’ve just described, and I’m going to run through them just a little bit more.

Climate change & x-risk

Climate change and existential risk. Ord puts the risk at 1 in 1,000. I’m reading the media, and the media is definitely biased in favor of trying to convince the world to take climate change more seriously. But I will say the degree to which warming is happening faster than anybody predicted 10 years ago and the degree to which the consequences are different and more severe, I think bringing some humility around our capacity to predict, it definitely feels like things could spin more out of control. But even at one in 1,000, Ord said it should be a central global priority, which is where he places it. Then I’ll just remind everyone that the short-term impact of climate change is massive, massive refugee crises and other significant problems, especially in the global south. Climate change poses a widening threat to national security.

Food security & x-risk

Food security and existential risk. Talking about food security and the fact that we’re currently 1.27 billion metric tons of food being fed to farm animals. If that doubles by 2050, it would absolutely drive up harm in global development, malnutrition, and starvation. As Jean Ziegler said, “It is a crime against humanity to cycle so many crops into chickens and pigs when they could be going to feed human beings.” So Matt Spence, a former official in the Department of Defense in the United States as well as the National Security Council, talks about how food security is what really keeps people up at NSC and DOD at night. Even more than many other risks. Obviously not going to surprise anybody in this room that conflict over food, conflict over resources is one of the more common sources of conflict, which could spiral out of control.

Water wars & x-risk

Water wars are basically the same argument. Massive water needs for industrial animal agriculture—that is slated to double through 2050. It’s already a crisis and could spiral out of control in addition to just the short-term global health and well-being issues with people not having water, not having food, and climate disruptions do have a significant possibility of leading to great powers conflict. Threat of conflict over war is growing.

Other environmental harms

And then Ord says, “Other environmental harms,” and it’s probably intuitive for everybody in this room, but if you’re doing something that in the best case requires nine times the resources of producing the same product in a different way. In other words, chicken is the most efficient animal at turning crops into meat, takes 9 calories in to get 1 calorie back out, and as I mentioned, that’s nine times the water, nine times the land, and nine times the pesticides and herbicides. The UN released a report about 15 years ago now called “Livestock’s Long Shadow,” and they said, “Animal agriculture contributes to problems of land degradation, climate change and air pollution, water shortage and water pollution, and loss of biodiversity.” And they conclude that the meat industry is one of the most significant contributors to the most serious environmental problems at every scale from local to global. That’s now. Double that by 2050. And one in 1,000. I don’t know if Toby is including the idea that this will double through 2050 in his calculations, but it’s getting significantly worse. Our only hope of turning it back is to replace the products. We’re simply not going to convince the world to eat less meat.

Global health (AMR/Pandemics) & x-risk

And this is the one that I want to spend just an extra minute or two on is pandemic risk. So Toby kind of goes back and forth between one in 10,000 and one in 2,000, and his quote is, “If we take the fossil record as evidence that the risk was less than one in 2,000 per century, then to reach 1 percent per century would be at least 20 times larger,” and he says this seems unlikely. And I’ll just note that in 1800, thinking about the fossil record, the world was consuming 10 million metric tons of meat, in 2000, 350, by 2050, something like 750 million metric tons of meat will be consumed on an annual basis. So I’m not sure it makes sense, and if it’s true that of the seven most likely causes, increased meat consumption is two of them and is linked to six of them, I think we may be extrapolating in a way that doesn’t actually align with the actual risk.

From a short-termist standpoint, I’ll remind people that COVID-19, for people who are beginning to think about economic development as a cause area and for people who are thinking about global poverty, of course, both of these are more short-termist rather than longtermist, as a cause area. COVID-19 was not particularly transmissible. It wasn’t particularly deadly, and still it cost the global economy trillions of dollars, killed millions of people, and sent more than 100 million people into dire poverty all in the global south.

Moral circle expansion

Then moral circle expansion, Will talks about this in his book obviously, but he says, “If we can improve the values that guide the behavior of generations to come, we can be pretty confident that they will take better actions even if they’re living in a world very different from our own, the nature of which we cannot predict.” This is pretty standard in animal-protection circles, maybe a little less standard outside of animal-protection circles, the idea that if the vast majority of people in society are eating meat on a regular basis, they’re simply not going to reconcile their internal ethics with the idea that animals matter. If how you feed yourself is you pay people to factory-farm animals, it becomes a lot harder to think about the argument for moral circle expansion, including animals in that moral circle. So if we can get to a world where animals don’t have to be slaughtered for meat and the animals who are slaughtered for meat are on smaller-holder farms or pastoralists or regenerative agriculture, which continues in the vision that we’re thinking about, which I’m happy to chat more about, but that does widen the moral circle in ways that could teach AI going forward what values look like, so values lock in.

The case for alternative proteins

So this is the central theme of the talk and I encourage people to pressure-test that. Just think about it and feel free to push back if you disagree, but alternative proteins, we think, are the only thing that can scale globally and probably the only thing that’s substantially like to work even in developed economies.

GFI- we’re basically two alternative proteins, what Environmental Defense or the World Wildlife Fund are to things like renewable energy and electric vehicles. We are single-mindedly focused. Our entire endeavor is to create a world where plant-based meat and cultivated meat taste the same or better and costs the same or less so that they can displace industrial animal agriculture.

GFI uses the OKR system that Google popularized. Everything we do fits into five objectives. Under each objective, we have somewhere in the order of five to eight key results. Our programmatic areas basically break down into science, policy, and corporate engagement.

We are, at root, a scientific think tank. Until GFI came along, nobody had mapped the technological readiness of plant-based meat or cultivated meat. When we started, we weren’t sure whether we were going to do cultivated meat, so two of the first six people I hired in June of 2016 were scientists. Their first charge was to figure out whether cultivated meat was viable or whether cultivated meat was science fiction. And they dived in, and the more they dived in, the more viable we decided we thought it was and the more viable the entire community thinks it is. But we do a lot of original research. Our number one thing is building global scientific communities and basically open-sourcing how we get from here to price and taste parity. So publishing peer reviews and other articles focused on letting the entire world know what it looks like to make cost-competitive and taste-competitive plant-based and cultivated meat. We have monthly Science of all protein webinars and lots of technical workshops, et cetera. These are some of the papers that we have published that are focused on, “What does it look like to get plant-based meat and cultivated meat to price and taste parity?” We also have what we call our Alt Protein Project, which is a super rigorous college program. It is a rigorous application process. It is a rigorous training process. All of the Alt Protein Projects also have to have objectives and key results, and they have to report three times a year how their work is tracking against their key results.

These are some of the resources for scientists which you can find if you go to gfi.org/science. And policy—for our global battle cry, we agree with what I think is a fairly common assumption in EA that if you have a cause area that you can get governments excited about, you can have 100,000x multiplier impact. The way I think about it is, we try to take our budget, which will be about $32 million this year across the six GFIs, and turn it into $10.1 billion in government funding. So we’re really thinking about what it looks like to convince governments that they’re currently funding climate-mitigation efforts, biodiversity efforts, and global health efforts. This is an incredibly tractable and important thing for governments to be setting up research centers focused on and for governments to be incentivizing private-sector activity. So that’s our global battle cry, that governments should be funding this, and $10.1 billion is our current goal, $4.4 billion for R and D, and $5.7 billion for private-sector incentives. And these are just from the last couple of months.

The US government, we convinced them to include alternative proteins in their bold goals for US biotechnology and biomanufacturing. About 8 months ago, it was in their national strategy for advanced manufacturing. This is Sanah Baig, who is Deputy Under Secretary for USDA, for the part of USDA that’s most important to us. Her department oversees the Office of the Chief Scientist, the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the Agriculture and Food Research Institute, Agricultural Research Service, and Economic Research Service. And just in the last 3 or 4 weeks, she has been at a ministerial dinner that we organized, an event at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a panel that I was on at Agricultural Innovation Mission for Climate alongside the governments of the Netherlands, the UK, the WTO and then Sanah Baig for USDA, all talking about alternative proteins and the importance of government prioritizing that. So number one goal, advocate for public investment, and we also do NGO advocacy, and work on cultivated-meat regulation.

GFI is not taking on industry, so GFI is not trying to take away subsidies. We’re not trying to tax meat. This is our entire policy goal. One, we want funds for open-access science. Two, we want to incentivize private-sector science, and, three, we want to incentivize private-sector R&D and manufacturing. The climate bill that is the biggest climate bill in the history of the world, oddly enough called the Inflation Reduction Act in the United States, all of it is positive. None of it is “penalize fossil fuels, penalize gas-powered cars.” All of it is affirmative. We’re taking our page from that and not focused on taking things away.

I will skip the Global Innovation Needs Assessments other than to say it’s the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and ClimateWorks Foundation. They said, by 2050, there could be $1.1 trillion in gross value added to the economy from alternative proteins and 10 million jobs.

And then the third pillar of the GFI three legs of the stool, the third leg of the stool, is industry engagement, and we do everything from pre-entrepreneur all the way up to relationships with the really big meat and food companies. The thing that I think we’re doing that is most important is, we have excellent relationships with Nestlé and ADM, the two largest food companies in the world, as well as JBS, Tyson, Cargill, Smithfield, and BRF, which are the five largest meat companies in the world. And our message to the meat companies and the food companies is that this is the future of meat production, and you can be part of it, or you can not be part of it. Analogizing the advent of digital photography, Canon took advantage. Kodak did not take advantage. Kodak went bankrupt. Canon thrived. “Do you want to be Kodak, or do you want to be Canon?” is essentially the pitch. Fortunately, all of the major foods and meat companies are falling into the, they want to be Canon, which obviously makes our work so much easier on the policy front if major corporations are supporting rather than opposing it. We also do monthly business of all protein webinars and lots and lots of other industry and other webinars. Here are some of the resources for industry, which you can find at gfi.org/industry.

Right now, we have about 190 people across six areas of the world. We picked the areas of the world with a sum total of zero interest in how much meat the country consumes and zero interest in the size of the population. So if you go to our 2021 year in review, there’s a light that looks like this and explains each country. There are basically just two variables. Does the country fund significant amounts of science focused on global health and/or climate, and do they have world-class scientific institutions? Because again, science in Israel or Singapore, we don’t care what people eat in Israel and Singapore, but science there can impact this entire industry in ways that are very exciting.

We were delighted that Giving Green, which is an EA climate charity evaluator, picked GFI as one of their top five choices for high-impact climate philanthropy. Here’s how they explain it: We do tens of thousands of hours of research so that you don’t have to. I’m very gratified about that selection. Animal Charity Evaluator has selected GFI as one of the four most impactful charities for animals, obviously for taking animals out of food production altogether.

And just to close, again, Dr. Rockström, humanity does indeed pose a threat to the stability of the planet. We need a new agricultural revolution. We’ve been making meat in the same exact way for 12 thousand years, funneling crops through animals. It is way past time for an update, and we think that this is the way that we can scale solutions globally. And we think it’s the only way we can scale solutions globally. Thank you very much. I’m excited to hear what people have to say.

Thanks for your work. I appreciate people doing real work, and at some level I feel bad for contributing to a Forum culture where people in the peanut gallery consistently shout down people doing real work on the ground. Nonetheless, here are my quick takes:

I think if someone starts from an impartial altruistic attempt at making the long-term future go well, it will be rather surprising if they landed on alternative proteins as one of the most likely ways to make sure the future goes well. Given the probable heavy-tailed distribution of impact, it will be further surprising if this is through a number of disjunctive channels that are each plausibly equally valuable. Additionally, it sure will be strange if people who started working on alternative proteins for entirely unrelated reasons somehow stumbled upon one of the best ways at making the long-term future go well. Finally, it’s kind of surprising, and perhaps suspicious, that you and/or GFI are making a claim that happens to line up well with your ideological and perhaps financial incentives.[1]

I apologize for not engaging with this post’s object-level arguments. They might well be correct. (For what it’s worth, I personally find the values-spreading now-> people have better values during the hinge of history → some form of lockin causes the future go well theory of change to be the most plausible[2]). But I do think the evidential bar for me to believe this posts’ arguments is rather high, and readers can judge for themselves whether these arguments meet such a bar.

Indeed the one time I tried to do a deep dive into adjacent research in a similar domain, I discovered elementary errors that consistently shaded in one direction.

I do not know what is the latest or best treatment of this argument, but I think I personally like Michael Dickens’ 2015 arguments here and here.

Linch, thanks so much for your comment. I think I agree with all of it, and I was pretty confused initially, b/c I didn’t realize the transcription error.

But yes, as David notes, the transcript flipped my point: I am not arguing that any of the external costs of alt proteins clock in at anywhere near a 1 in 10 or 1 in 30 X-risk.

My point is just (as noted in # 3 of my synopsis) that they are “sufficiently high… to warrant attention from longtermists” who are in a position to advance more than one thing (e.g., working in government or philanthropy, where you can have a portfolio).

Examples:

- Government: Adding alt proteins to one’s portfolio will often be fairly easy—e.g., at OSTP or NSF or in a congressional office.

- Philanthropy: Some philanthropists will insist on giving with a focus on global health, biodiversity, or climate; where that happens, steering them toward alt proteins can make a lot of sense.

Apologies for the transcription error—fixed, as detailed in my next comment.

I liked your comment a lot, but I’m pretty sure you misunderstood a big part of the argument because there’s a pretty big typo in this post.

In the original recording(4:07) Fredrich argues that advancing alternative proteins should be a significant part of longtermist thinking, but not that they’re “one of the best ways at making the long-term future go well” or even “on par with AI risk or bioengineered pandemics”.

But this transcript makes it seem like he is saying the opposite in the intro:

I think you still bring up a lot of good points though.

I appreciate your catching this, David—I would not have noticed this and would have been pretty confused by Linch’s comment. I did go back and edit the transcript to align with the video, and I appreciate your noting this.

Edited per your excellent comment that the text flipped the meaning of the video:

The third point is that alternative proteins address multiple risks to long-term flourishing and they should be a priority for longtermists. I’m not going to try to convince you they should be the priority or that they’re on par with AI risk or bioengineered pandemics. But I am going to try to convince you that unless you are working for an organization that is focused on one thing, you should add alternative proteins to your portfolio if you are focused on longtermism.

Also slightly edited this bit to better capture the video:

[16:40] In Toby Ord’s book The Precipice he says, “Risks greater than 1 in 1,000 should be central global priorities.” … my goal is not going to be to convince you [that] if you’re working on unaligned AI or bioengineered pandemics (What are they − 1 in 10 and 1 in 30 existential risks) that this is something that you should do instead. But if you are working in policy… you can have a more diverse portfolio than unaligned AI and bioengineered pandemics. In fact, it’s probably to our benefit to have a more diverse portfolio. And I would contend that alternative proteins should be a part of that portfolio for all of the reasons that I’ve just described...

[EDIT: Note that this might be a misunderstanding—see Benny’s reply below]

Thank you for this!

What is the mechanism by which the failure of alternative proteins doubles harm from climate in 2050? APs are clearly a significant climate solution and worthy of more support (I regularly send donors in the direction of GFI), but this seems a very strong claim.

Maybe I’m misunderstanding, but I think the article is referring to projections that meat production will double by 2050. He’s not claiming that climate change will be twice as bad without alt proteins. Instead, he’s saying that harms from meat production will double by 2050 without alt proteins.

Seems accurate to me, though I see how it might be confusingly worded.

Thanks for catching this, I indeed understood this as “the harms from climate change are doubling” but I can see how your interpretation seems more likely to be correct and would be accurate.

I find it very confusingly worded given it says just above “causing significant and immediate harms to billions of people” and then says “these harms”.

I’m sorry for my shoddy wording. Yes, my point (thanks for jumping in, Benny!) was only that if animal agriculture doubles by 2050, that will double these harms, which are already quite severe. I updated bullet two of my introduction to make this clear.

Hi Bruce,

Thanks for writing about this! I tend to believe looking into the longterm impacts of interventions typically classed as neartermist is valuable.

A few thoughts:

If the extinction risk from “natural” pandemics is low, and humanity learns a lot from them, they could decrease the risk from more severe pandemics.

I think more global warming might be good to mitigate the food shocks caused by abrupt sunlight reduction scenarios.

It is quite unclear whether global warming is good/bad for wild animals, whose welfare is likely much larger than that of farmed animal and humans.

Alternative proteins require less resources, so they will push towards decreasing the amount of slack in the agricultural system, and therefore decrease resilience to food shocks. This will arguably increase the risk from extinction due to nuclear war, which can cause severe food shocks via a nuclear winter.

Regarding this last point, I wrote that:

My current overall take is that I do not know whether more alternative proteins is good/bad from a longtermist perspective. However, I would say it is a relevant topic to think about!

I would also say we should beware surprising and suspicious convergence. For example, to cost-effectively decrease the risk of human extinction due to:

Food shocks, one could invest in resilient food solutions. Some of these are alternative proteins, like single-cell protein, but not all of them.

Engineered pandemics, one could invest in far-UVC and PPE.

Thanks so much for your comments, Vasco—I appreciate your engagement, and I find your comments fascinating.

Thanks, Bruce! I appreciate your open-mindedness too.