In defence of epistemic modesty [distillation]

This is a distillation of In defence of epistemic modesty, a 2017 essay by Gregory Lewis. I hope to make the essay’s key points accessible in a quick and easy way so more people engage with them. I thank Gregory Lewis for helpful comments on an earlier version of this post. Errors are my own.

Note: I sometimes use the first person (“I claim”/”I think”) in this post. This felt most natural but is not meant to imply any of the ideas or arguments are mine. Unless I clearly state otherwise, they are Gregory Lewis’s.

What I Cut

I had to make some judgment calls on what is essential and what isn’t. Among other things, I decided most math and toy models weren’t essential. Moreover, I cut the details on the “self-defeating” objection, which felt quite philosophical and probably not relevant to most readers. Furthermore, it will be most useful to treat all the arguments brought up in this distillation as mere introductions, while detailed/conclusive arguments may be found in the original post and the literature.

Claims

I claim two things:

You should practice strong epistemic modesty: On a given issue, adopt the view experts generally hold, instead of the view you personally like.

EAs/rationalists in particular are too epistemically immodest.

Let’s first dive deeper into claim 1.

Claim 1: Strong Epistemic Modesty

To distinguish the view you personally like from the view strong epistemic modesty favors, call the former “view by your own lights” and the latter “view all things considered”.

In detail, strong epistemic modesty says you should do the following to form your view on an issue:

Determine the ‘epistemic virtue’ of people who hold a view on the issue. By ‘epistemic virtue’ I mean someone’s ability to form accurate beliefs, including how much the person knows about the issue, their intelligence, how truth-seeking they are, etc.

Determine what everyone’s credences by their own lights are.

Take an average of everyone’s credences by their own lights (including yourself), weighting them by their epistemic virtue.

The product is your view all things considered. Importantly, this process weighs your credences by your own lights no more heavily than those of people with similar epistemic virtue. These people are your ‘epistemic peers’.

In practice, you can round this process to “use the existing consensus of experts on the issue or, if there is none, be uncertain”.

Why?

Intuition Pump

Say your mom is convinced she’s figured out the one weird trick to make money on the stock market. You are concerned about the validity of this one weird trick, because of two worries:

Does she have a better chance at making money than all the other people with similar (low) amounts of knowledge on the stock market who’re all also convinced they know the one weird trick? (These are her epistemic peers.)

How do her odds of making money stack up against people working full-time at a hedge fund with lots of relevant background and access to heavy analysis? (These are the experts.)

The point is that we are all sometimes like the mom in this example. We’re overconfident, forgetting that we are no better than our epistemic peers, be the question investing, sports bets, musical taste, or politics. Everyone always thinks they are an exception and have figured [investing/sports/politics] out. It’s our epistemic peers that are wrong! But from their perspective, we look just as foolish and misguided as they look to us.

Not only do we treat our epistemic peers incorrectly, but also our epistemic superiors. The mom in this example didn’t seek out the expert consensus on making money on the stock market (maybe something like “use algorithms” and “you don’t stand a chance”). Instead, she may have listened to the one expert she saw on TV, or one friend who knows a bit about investing, or she thought of this one ‘silver bullet’ argument that decisively proves she is right.

Needless to say, consulting an aggregate of expert views seems better than one expert view from TV, and a lot better than one informed friend. And of course, the experts already know the ‘silver bullet’ argument, plus 100 other arguments and literature on the issue. Sometimes, all of this is hard to notice from the inside.

Why weigh yourself equally to your epistemic peers?

Imagine A and B are perfect epistemic peers regarding identifying trees. I.e., they are identically good at all aspects of forming accurate beliefs about what type a tree is. They disagree on whether the tree they are looking at is an Oak tree. A is 30% sure it’s an Oak tree, B is 60% sure. What should you, only knowing these 2 guesses, think is the chance of it being an Oak tree?

Since A’s and B’s guesses are identically accurate, it seems most sensible to take the average in order to be closest to the truth. And even if you were A or B, if you want to be closest to the truth, you should do the same.

So if you weigh yourself more heavily than your epistemic peers, you expect to become less accurate.

Modesty gets better as you take more views into account

If you take a jar with Skittles and have all of your friends guess how many Skittles are in the jar, their average will usually be closer to the truth than their individual guesses. The more friends you ask, the more accurate the average will be. Epistemic modesty outperforms non-modesty more and more as you take more and more views into consideration. This corresponds to the intuition that the individual inaccuracies your friends have tend to cancel each other out.

Caution with ‘views all things considered’

It is important to distinguish between credences by one’s own lights and credences all things considered. If you confuse a person’s (say A’s) credences by their own lights with their credences all things considered, things go wrong:

A’s credences all things considered should include everyone’s own reasoning (counted once), weighted by their epistemic virtue. You now want to form credences all things considered. You include everyone’s own reasoning counted once, but for A you accidentally include his all things considered credences. Now, in total, you have counted everyone more than once since A has also already counted them. (Except A himself; you have counted him less than once.)

Against justifications for immodesty

Being well-informed/an expert

People often assume being well-informed gives them the ability to see for themselves what is true, as opposed to trusting expert consensus. Strong epistemic modesty responds that they have merely reached epistemic peerhood with many other people who’re also well-informed. And experts are still epistemically superior. In short, you are not special. Your best bet is a weighted average, as is everyone else’s.

And even if you are an expert, you need to keep in mind that you are not epistemically superior to other experts. And if a weighted average is their best bet, it is also yours.

‘Silver bullet’ arguments, private evidence, and pet arguments

What if you think you have a clear ‘silver bullet’ argument that decides the issue, so there is no need to defer to the experts?

First, you are probably wrong. It is quite common for people to believe they have found a ‘silver bullet’ argument proving X while, in reality, experts are well aware of the argument and nonetheless believe Y (not X).

What if you believe your silver bullet argument is not well-known to the experts?

Again, you are probably wrong. Most likely, this argument is already in the literature, or too weak to even be in the literature.

What if not? If not, you should believe that your argument would actually be persuasive to an expert once they learn about it. Simulating this test in your head might already make you feel a bit less confident. The best test would be to actually ask an expert of course.

“Smart contrarians”

What about cases where a smart person has an unpopular contrarian take but ultimately proves to be right? Here, strong epistemic modesty would be bad at favoring the correct view over the expert consensus. Only slowly, individuals would accept the contrarian take and slowly shift the consensus toward the truth. This delay may be very costly, for example, with the initially contrarian take that we should abolish slavery.

I claim modesty may be slow in these cases, but that’s appropriate. Most often, the unpopular contrarian take does not prove to be right and so modesty performs better. In the words of the author: “Modesty does worse in being sluggish in responding to moral revolutions, yet better at avoiding being swept away by waves of mistaken sentiment: again, the latter seems more common than the former.”

Modesty might be bad for progress

If everyone just defers for all their opinions, will people stop looking at the object-level arguments, stop thinking and critiquing, and never make any progress anymore?

Well, it is not impossible under strong epistemic modesty to look at the object level and make progress. You can still think for yourself, and change your credences by your own lights. It’s just that your credences all things considered won’t shift much.

I grant that possibly, this makes it psychologically harder to feel motivated to think for oneself, which would be bad for progress. If this is the case, we might want to allow for exceptions from modesty for the sake of progress while moderating the cost that less accurate views will produce. But beyond that, we should not consider immodesty desirable.

Complications in using strong epistemic modesty

Using strong epistemic modesty in practice is far from easy and clean-cut all the time. I will now introduce some complications to the story. These are also often used as justifications for immodesty, so they are a continuation of the last section.

Smart contrarians again

Contrarian takes may usually be wrong, but what if we can recognize correct contrarian takes and so outperform strong epistemic modesty in these cases? The author responds that, empirically, some people may identify correct contrarian takes at a rate better than chance, but no one can identify them more often than not. This means the consensus view is still more likely to be correct. However, your confidence in the consensus view is justified to fall a bit if a contrarian with a good track record disagrees.

The experts are irrational

Often one is tempted to discard the experts due to being biased and irrational, ideologically motivated, “bad incentives in academia”, etc.

The first question to ask is: Are you better in this respect? How do you know you aren’t suffering from the same biases, or another ideological motivation, or similar?

For example, if you think the experts have a poor track record of making predictions in their field, ask yourself: Do you have a better track record? If not, they are still your epistemic superiors, albeit to a lesser extent than if they had a good track record.

Even if you are clearly superior to the experts on one epistemic virtue, ask yourself: Are they still your epistemic superiors overall? Do their years of experience, proven excellence, etc. maybe still give them an edge over you?

Finally, even if you are able to thoroughly debunk the expert class, ask yourself: Is there maybe another expert class which remains epistemically superior to you? If, e.g., professional philosophers are too irrational and driven by bad incentives, wouldn’t there remain lots of subject experts epistemically superior to you? In the author’s words: “The real expert class may simply switch to something like ‘intelligent people outside the academy who think a lot about the topic’”.

What even is the expert consensus?

Usually, it is far from easy to “just defer to the experts”. Experts disagree and who are the experts anyway? Usually, there are several clusters of potential experts around an issue, and it’s not easy to decide who’s trustworthy. Things get messy.

Author’s example: “Most people believe god exists (the so called ‘common consent argument for God’s existence’); if one looks at potential expert classes (e.g. philosophers, people who are more intelligent), most of them are Atheists. Yet if one looks at philosophers of religion (who spend a lot of time on arguments for or against God’s existence), most of them are Theists—but maybe there’s a gradient within them too. Which group, exactly, should be weighed most heavily?”

To figure out weightings, here are a couple of things to do:

Figure out how close the question is to the various potential experts’ realm of expertise.

Weigh up the potential experts’ epistemic virtues. (Philosophers of religion are selected for being more religious. Maybe this is bad for their epistemic virtue regarding issues of religion.)

Think about whether they are forming their views independently. (On the topic of god, they most certainly aren’t.)

If people from expert class A have talked to expert class B and changed their minds, this provides evidence in favor of B’s views.

If a third party has to make a decision (that it has actual stakes in), and has to weigh up expert classes A and B, its decision might indicate which experts they trusted.

Unfortunately, this can get very messy and invites room to introduce your own bias and errors.

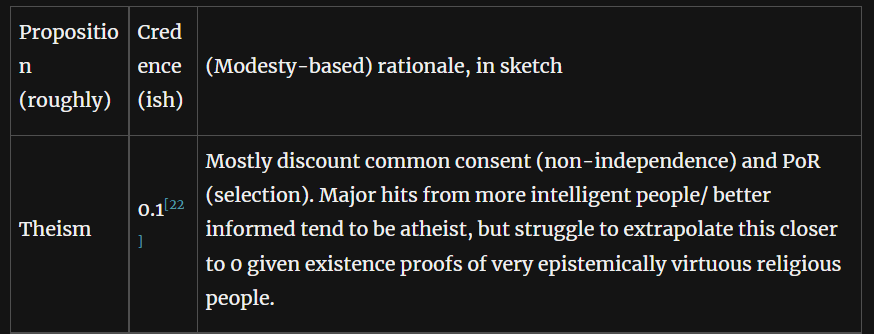

In the case of “Does god exist?”, the author thus arrives at a credence of ~10% for yes:

Claim 2: Modesty for Rationalists/EAs

The second claim of this post is that rationalists and EAs in particular have need for more epistemic modesty. Bear in mind though that the original post is 5 years old now, and the author might think these problems have since changed.

Rationalist/EA exceptionalism

It is all too common for an EA or rationalist to proclaim they have achieved a novel insight, or solved an age-old problem, when they are clearly an amateur at what they’re doing. We seem to think our philosophy and rationality give us an edge over experts spending decades in their fields. Often, the EA or rationalist hasn’t even read into the relevant literature. Sometimes, projects in our communities seem groundbreaking to us, but domain experts report they are misguided, rudimentary, or simply reinventing the wheel. This is bad for our communities’ epistemics, impact, and optics to the outside. It would be better if we checked with the literature/experts whenever we think we are breaking ground. Most often, we are probably not.

Breaking ground is different from just summarizing existing knowledge in a field—if you aren’t claiming to break ground, you don’t actually need to be up to speed with the experts.

Pathological modesty

Ironically though, there is actually lots of deferring happening in our community. This is deferring to ‘thought leaders’ of the movement who hold what would commonly be seen as quite eccentric views while being far from subject experts in the relevant fields. Our community reveres these people and accepts their worldview with inadequate modesty.

Conclusion

To conclude, I’d simply like to restate the two claims defended in this post. These are the two messages I’d like you to meditate on:

You should practice strong epistemic modesty: On a given issue, adopt the view experts generally hold, instead of the view you personally like.

EAs/rationalists in particular are not epistemically modest enough.

I would be very curious for Gregory’s take on whether he thinks EAs are too epistemically immodest still!

Interesting. I think there are two related concepts here, which I’ll call individual modesty and communal modesty. Individual modesty, meaning that an individual would defer to the perceived experts (potentially within his community) and communal modesty, meaning that the community defers to the relevant external expert opinion. I think EAs tend to have fairly strong individual modesty, but occasionally our communal modesty lets us down.

With most issues that EAs are likely to have strong opinions on, here are a few of my observations:

1. Ethics: I’d guess that most individual EAs think they’re right about the fundamentals- that consequentialism is just better than the alternatives. I’m not sure whether this is more communal or individual immodesty.

2. Economics/ Poverty: I think EAs tend to defer to smart external economists who understand poverty better than core EAs, but are less modest when it comes to what we should prioritise based on expert understanding.

3. Effective Giving: Individuals tend to defer to a communal consensus. We’re the relevant experts here, I think.

4. General forecasting/ Future: Individuals tend to defer to a communal consensus. We think the relevant class is within our community, so we have low communal modesty.

5. Animals: We probably defer to our own intuitions more than we should. Or Brian Tomasik. If you’re anything like me, you think: “he’s probably right, but I don’t really want to think about it”.

6. Geopolitics: I think that we’re particularly bad at communal modesty here—I hear lots of bad memes (especially about China) that seem to be fairly badly informed. But it’s also difficult to work out the relevant expert reference class.

7. AI (doom): Individuals tend to defer to a communal consensus, but tend to lean towards core EA’s 3-20% rather than core-LW/Eliezer’s 99+%. People broadly within our community (EA/ rationalists) genuinely have thought about this issue more than anyone else, but I think there’s a debate whether we should defer to our pet experts or more establishment AI people.

Why not add them together, and declare yourself 90% sure that it is an oak tree?

Or rather, since simply adding them together may get you outside the [0, 1] range, why not convert it to log odds, subtract off the prior to obtain the evidence, and add the evidence together, add back in the prior, and then convert it back to probabilities?